WAIKNA;

OR,

ADVENTURES

ON THE

MOSQUITO SHORE.

BY SAMUEL A. BARD.

WITH SIXTY ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS.

329 & 331 PEARL STREET.

1855.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1855, by

Harper & Brothers,

In the Clerk’s Office of the Southern District of New York.

Scene.—A lonely shore.

Enter Yankee and Mosquito Man.

Well, my dark friend, who are you?

“Waikna!” A man!

And what is your nation?

“Waikna!” A nation of men!

Pretty good for you, my dark friend! There was once a great nation—a few old bricks are about all that remains of it now—whose people were proud to call themselves —— but then what do you know about the Romans?

“Him good for drink—him grog?”

Bah! No!

“Den no good! bah, too!”

Exeunt ambo.

Now such a dialogue took place, or might have taken place, on the Mosquito Shore. For all[vi] artistic purposes it did take place; and, as my book is chiefly devoted to the Mosquito man and his country, it shall be called Waikna—a word that, in the Mosquito tongue, means simply Man, but which is proudly claimed as the generic designation of the people of the entire coast.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Jamaica, and how the Author got there—A solemn Soliloquy—An Artist Tempted—Painting a Portrait—The Schooner Prince Albert—Captain and Crew—Antonio—Superstitions—Gathering of the Storm—A Scene of Terror—The Shipwreck | 13 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| “El Roncador”—The Escape—Coral Cays—Scene with the Dead—A Night of Fever—Delirium—Island Scenes—Turtles—A cruel Practice—Sail ho!—An Encounter—Revolvers versus Knives—Departure from “El Roncador”—Island of Providence—A Scene of Revelry—Away for the Mainland | 36 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Approach to Bluefields—An Imperial City—New Quarters—Mr. Hodgson—The Mosquito King—“George William Clarence!”—Grog versus Gospel—The “Big-Drunk”—A Mosquito Funeral—Singular Practices—Superstitions—An ill-fated Colony—Sad Reflections | 56 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Rama Indians—Departure from Bluefields—Canoe Voyage—Strange Companionship—The “Haulover”—Our first Encampment—Epicurean Episode—Night under the Tropics—Life on the Lagoons—Pearl Cay Lagoon—Climbing after Cocoa-Nuts—A Solitary Grave—Mangroves—Soldier Crabs—Roseate Spoonbill—River Wawashaan—Deserted Plantation—Sambo Settlement—“A King-Paper”—Extraordinary Reception—Captain Drummer—King’s House—Vanilla Plant—Philanthropy—A Dance—“Spoiled Head”—Fire-light Fishing—Night Scene | 76 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

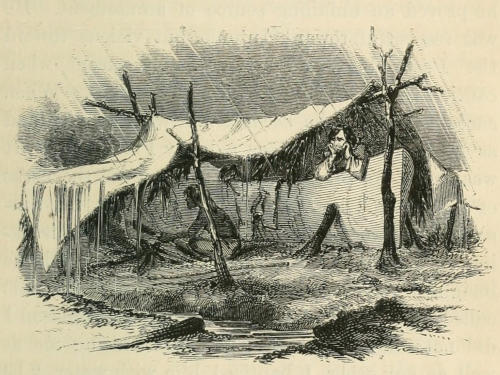

| Visit to the Turtle Cays—Spearing Turtle—Jumping Turtle—Return to the Lagoon—Off again—Native Indigo—Another Haulover—Tropical Torments—Braving the Bar—Great River—Temporal Camp—Continuous Rain—Doleful Dumps—Freaks of the Flood—Rain, Rain!—Craw-Fish—“El Moro”—The Manzanilla—Guavas—The Release | 105[viii] |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

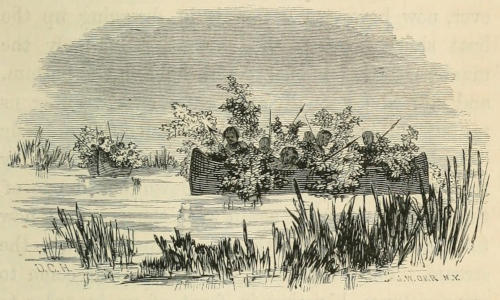

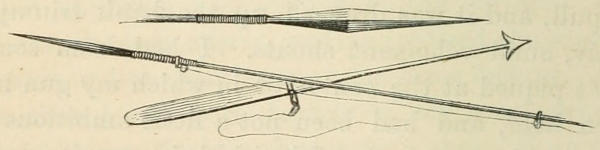

| On the River—Strong Currents—An Indian Village—A Woolwa Welcome—Ceremonious Reception—Relations of the Indians—Their Habits—A Tabooed Establishment—Projected Sport—Hunting the Manitus—Habits of the Animal—The Attack—Great Excitement—Successful Capture—Division of the Spoil—Instruments of the Chase—Another Epicurean Episode | 122 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Departure—The Plantain-Tree—Bisbire—Nocturnal Noises—“Stirring up the Animals”—At Sea Again—Mollusca of the Caribbean—Walpasixa—The Moonlit Ocean—Prinza-pulka River—Vines and Verdure—Savannahs—Village of Quamwatla—Inhospitable Reception—A Retreat—Fatal Encounter—A Trial of Cunning—Tropical Thunder-Storm—A Second Encounter—The Fight, and the Triumph—Flight—Asylum in the Forest—The Explanation | 138 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Tapir Camp—A Picturesque Retreat—Wild Life—Palm Wine—Queen of the Forest—Pine Ridges—Parrots and Paroquets—A Fright—“Only a Dante”—Trapping the Tapir—Successful Result—Narrow Escape—“An Army with Banners”—Honey-bees—Communion with Nature—Once more on the Lagoons | 162 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Lagoons of the Mosquito Shore—Indians and Sambos—Life among the Lagoons—Aquatic Birds—Silk-Cotton Tree—Water Plant—Night Traveling—Tongla Lagoon—Fishing—A Disagreeable Discovery—The Chase—Prospect of a Fight—Successful Device—Diamond cut Diamond—Safely off—Wava Lagoon—Attack of Fever—Primitive Physic—Poisonous Reptiles—My Poyer Boy Bitten—The Cure | 179 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Leave Fever Camp—Towkas Indians—Formal Reception—Singular Practices—Towka Marriage—Extraordinary Ceremonies—Presents Propitiatory—Shouldering the Responsibility—Marriage Festival—How to get Drunk—The End of it—Wild Animals—Indian Rabbits—The Curassow—Chachalaca—Gibeonite—River Turtle—Savory Cooking | 200 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Duckwarra Lagoon—Aboriginal Relics—Sandy Bay—Mosquito Fashions—Sambos of Sandy Bay—General Peter Slam—An English Captain—Brutality—Interference—A Drunken Debauch—Mishla Drink—Dances and Songs—A Sukia Woman—Opportune Warning—Hurried Departure—Power of the Sukias—Making Mishla—A Disgusting Operation | 215[ix] |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Cape Gracias—Its Inhabitants—Fine Savannah—Sambo Practices—Novel Mode of Hunting—Island of San Pio—Mangrove Oysters—Trial of the Sukia—A Mysterious Seeress—Superstitions of the Sambos—Wulasha and Lewire—Character and Habits of the Mosquitos—Drunkenness—Decrease—Festival of the Dead—New Plans—River Wanks or Segovia—Iguanas—Armadillos | 234 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| River Bocay—New Scenery—End of the Savannahs—Indian Village—The Messenger—A Night Adventure—Sanctuary of the Sukia—Hoxom-Bal, the Mother of the Tigers—Mysteries—Ruins among the Mountains—Serious Impressions—A Tale of Wanks River—Harry F. and the Padre of Pantasma | 251 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Up the Cape River—Imposing Scenery—Storm among the Mountains—Influence of the Moon’s Rays—River Tirolas—Mountain Streams—Picturesque Embarcadero—A Sweet Encampment—An Accident—Laid up—Send off the Poyer Boy for Help—Speedy Recovery—Monkeys—An Encounter with the Pigs—To Eat or to be Eaten, a wide Difference—Return of the Poyer—Abandonment of the Canoe—“El Moro” again—Ascent of the Mountains—Another Temporal—Reflections on Fire | 272 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Crest of the Mountains—A Desert Waste—Descent—Rio Guallambre—Gold Washing—The Poyer Village—Habits of the Poyers—Plantations—Poisoning Fish—Primitive Arts—Indian Naiads—Patriarchal Government—Departure—Rio Amacwass—Rio Patuca—“Gateway of Hell”—Approach to the Sea—Brus Lagoon | 290 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Arrival at Brus—A Festival—Hospitality—Loss of the Poyer Boy—Civilization of the Caribs—Cocoa-Groves—Sanitary Precautions—Wild-Fig or Banyan-Tree—Habits of the Caribs—Industry—The Mahogany-Cutters—Celebration of their Return—A Carib Dandy—Polygamy—Singular Practices—A Carib Crew—Departure—The Bay of Honduras—The Bottom of the Sea—Island of Guanaja—Night—Sombre Soliloquies—Antonio’s Secret—The Rousing of the Indians—Deep-laid Schemes of Revenge—The Voice of the Tiger in the Mountains | 312 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| A—Historical Sketch | 335 |

| B—Notes and Extracts | 354 |

| C—Mosquito Vocabulary | 363 |

| NUMBER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

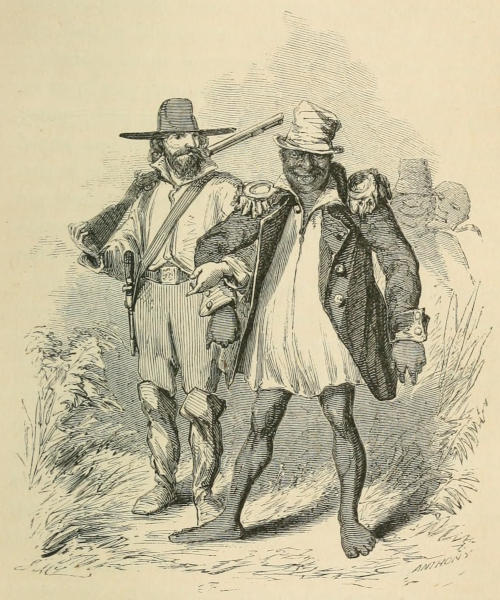

| 1. | ILLUSTRATIVE TITLE | 1 |

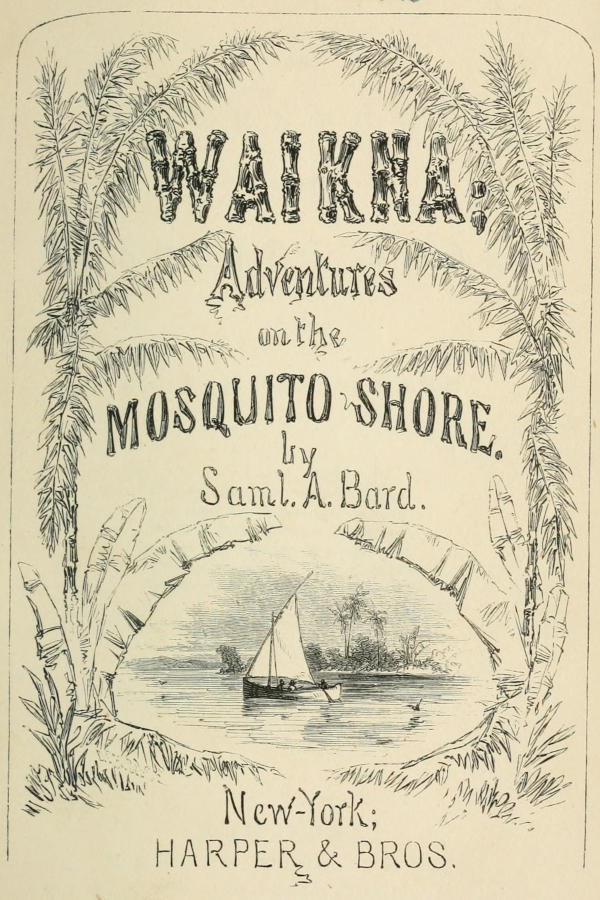

| 2. | MAP OF MOSQUITO SHORE | 12 |

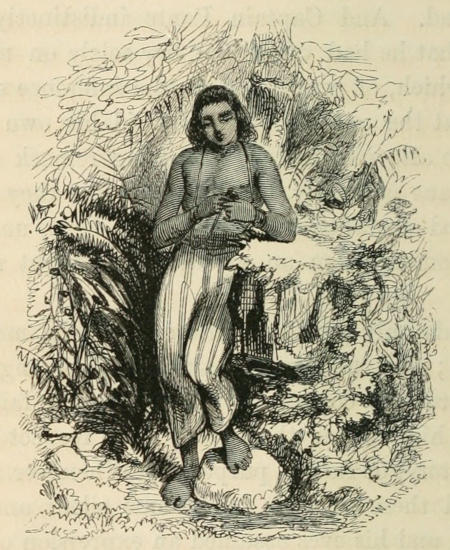

| 3. | THE ARTIST | 13 |

| 4. | MY LANDLADY | 22 |

| 5. | ANTONIO CHUL | 28 |

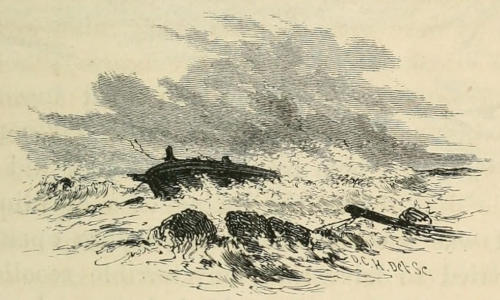

| 6. | THE SHIPWRECK | 35 |

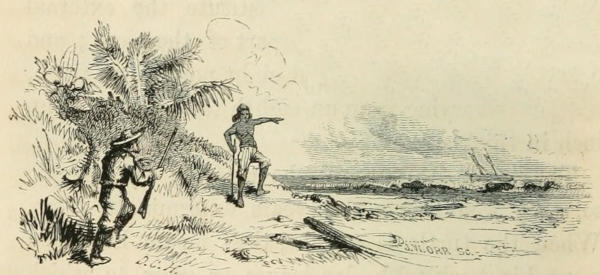

| 7. | THE ESCAPE | 36 |

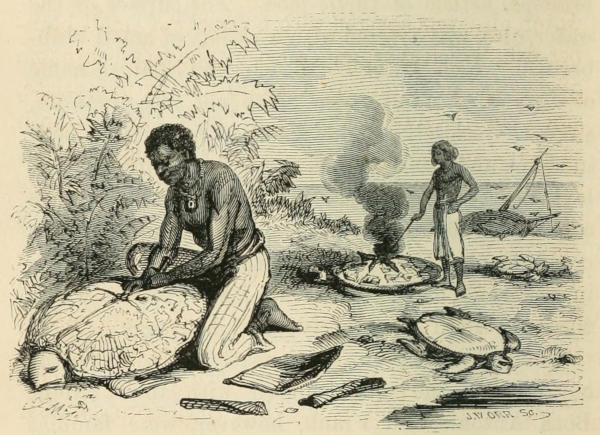

| 8. | “SHELLING” TURTLES | 46 |

| 9. | A SAIL! A SAIL! | 48 |

| 10. | “EL RONCADOR” | 52 |

| 11. | APPROACH TO BLUEFIELDS | 56 |

| 12. | GOING TO THE FUNERAL | 67 |

| 13. | A MOSQUITO BURIAL | 70 |

| 14. | AFLOAT IN THE LAGOON | 76 |

| 15. | CLIMBING AFTER COCOAS | 84 |

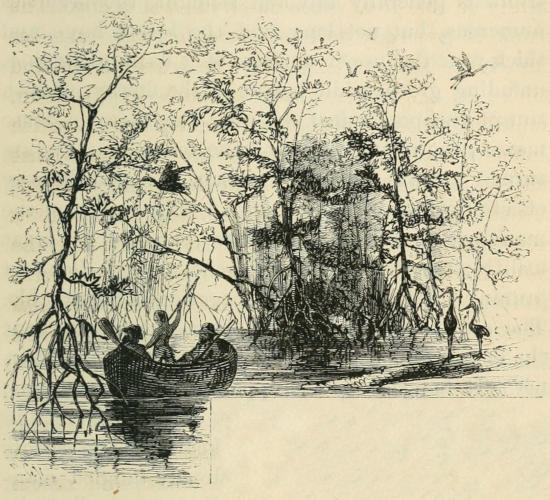

| 16. | A MANGROVE SWAMP | 85 |

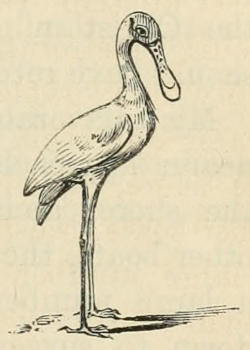

| 17. | THE ROSEATE SPOONBILL | 89 |

| 18. | CAPTAIN DRUMMER | 93 |

| 19. | TURTLE CAYS | 105 |

| 20. | SPEARING TURTLE | 109 |

| 21. | TEMPORAL CAMP | 117 |

| 22. | A FRESHET IN THE RIVER | 122 |

| 23. | HUNTING THE MANITUS | 133 |

| 24. | HARPOONS AND LANCES | 136 |

| 25. | TROPICAL VERDURE | 138 |

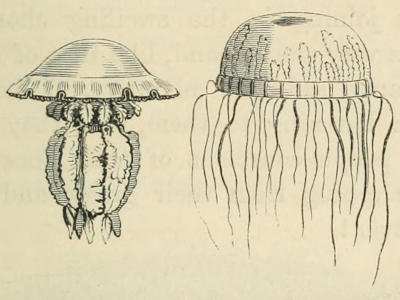

| 26. | MARINE MOLLUSCA | 143 |

| 27. | ON THE MOONLIT SEA | 144 |

| 28. | VILLAGE OF QUAMWATLA | 149 |

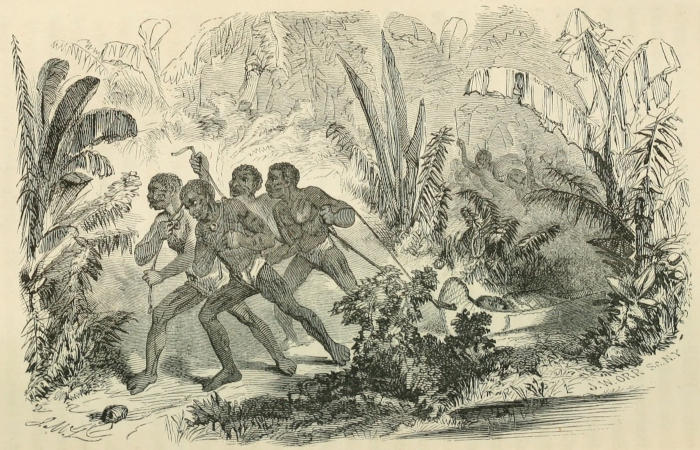

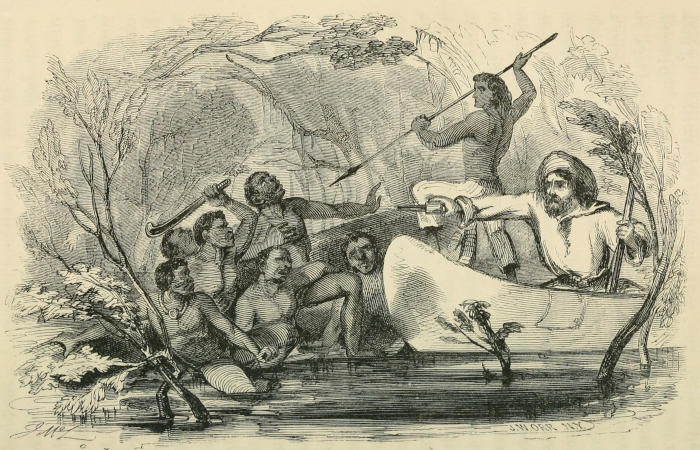

| 29. | FIGHT NEAR QUAMWATLA | 153 |

| 30. | TAPIR CAMP | 162 |

| 31. | PALMETTO ROYAL | 166 |

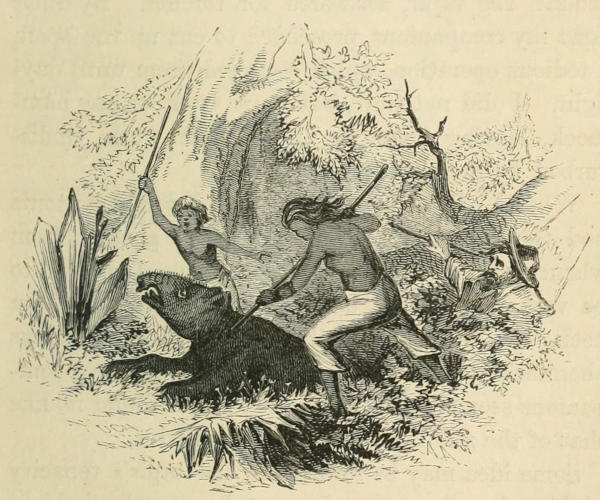

| 32. | THE DEATH OF THE TAPIR | 172 |

| 33. | BIRDS OF THE LAGOONS | 179 |

| 34. | LIFE AMONG THE LAGOONS | 182 |

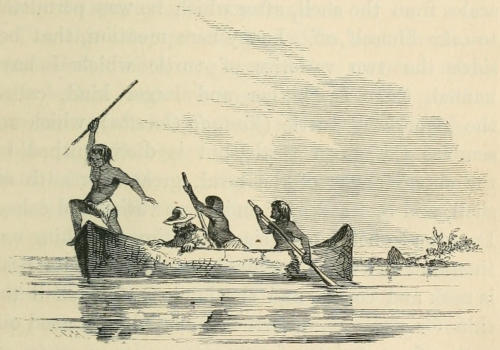

| 35. | CHASE ON TONGLA LAGOON | 189 |

| 36. | FEVER CAMP | 200 |

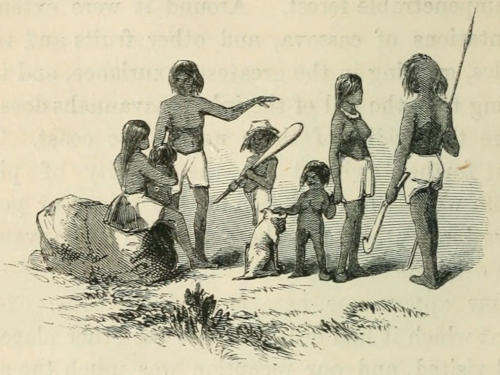

| 37. | TOWKAS INDIANS | 202 |

| 38. | THE END OF IT! | 210 |

| 39. | TOWN OF SANDY BAY | 215 |

| 40. | A GOLDEN IDOL | 217 |

| 41. | GENERAL PETER SLAM | 221 |

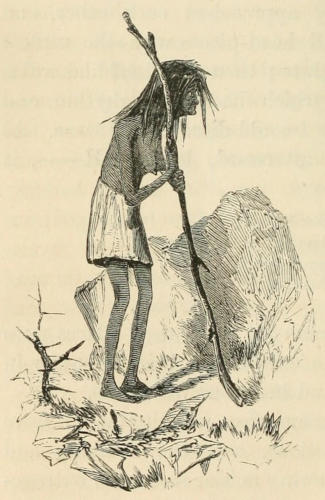

| 42. | SUKIA OF SANDY BAY | 228 |

| 43. | CAPE GRACIAS A DIOS | 234 |

| 44. | HUNTING DEER | 237 |

| 45. | RIVER BOCAY | 251 |

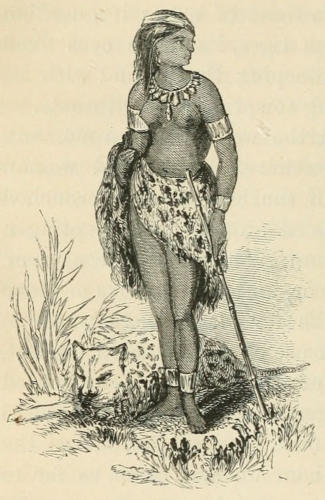

| 46. | THE MOTHER OF THE TIGERS | 256 |

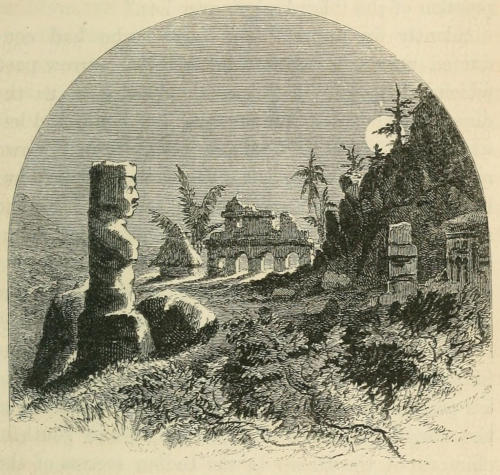

| 47. | SANCTUARY OF THE SUKIA | 259 |

| 48. | SCENERY ON THE RIVER WANKS | 272 |

| 49. | EMBARCADERO ON THE TIROLAS | 276 |

| 50. | THE WAREE | 283 |

| 51. | THE MOUNTAIN CREST | 290 |

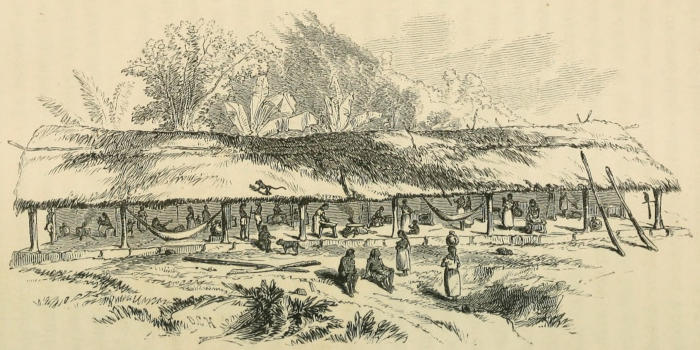

| 52. | A POYER VILLAGE | 295 |

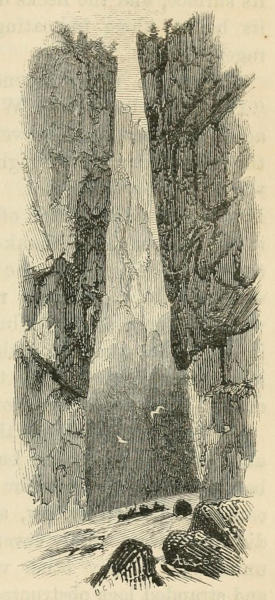

| 53. | “THE GATEWAY OF HELL” | 309 |

| 54. | VIEW AT BRUS | 312 |

| 55. | APPROACH TO GUANAJA | 325 |

| 56. | REVEALING THE SECRET | 332 |

MAP of Mosquito Shore

The route of the author is indicated in the Map by a dotted line.

A month in Jamaica is enough for any sinner’s punishment, let alone that of a tolerably good Christian. At any rate, a week had given me a surfeit of Kingston, with its sinister, tropical Jews, and variegated inhabitants, one-half black, one-third brown, and the balance as fair as could be expected, considering the abominable, unintelligible Congo-English which they spoke. Besides, the cholera which seems to[14] be domesticated in Kingston, and to have become one of its local institutions, had begun to spread from the stews, and to invade the more civilized parts of the town. All the inhabitants, therefore, whom the emancipation had left rich enough to do so, were flying to the mountains, with the pestilence following, like a sleuth-hound, at their heels. Kingston was palpably no place for a stranger, and that stranger a poor-devil artist.

The cholera had cheated me of a customer. I was moody, and therefore swung myself in a hammock, lit a cigar, and held a grand inquisition on myself, as the poets are wont to do on their souls. It ran after this wise, with a very little noise but much smoke:—

“Life is pleasant at twenty-six. Do you like life?”

Rather.

“Then you can’t like the cholera?”

No!—with a hurried pull at the cigar.

“But you’ll have it here!”

Then I’ll be off!

“Where?”

Any where!

“Good, but the exchequer, my boy, how about that? You can’t get away without money.”

There was a long pause, a great cloud of smoke, and much swinging in the hammock, and a final echo—

Money! Yes, I must have money!

So I got up, spasmodically opened my portmanteau,[15] dived deep amongst collars, pencils and foul linen, took out my purse, turned its contents on the table, and began to count.

Forty-three and a half, forty-four, forty-five, and this handful of small silver and copper. Call it fifty in all.

“Only fifty dollars!” ejaculated my mental interrogator.

Only fifty! responded I.

“’Twon’t do!”

I lit another cigar. It was clear enough, it wouldn’t do; and I got into the hammock again. Commend me to a hammock, (a pita hammock, none of your canvas abominations,) and a cigar, as valuable aids to meditation and self-communion of all kinds. There was a long silence, but the inquisition went on, until the cigar was finished. Finally “I’ll do it!” I exclaimed, in the voice of a man determined on some great deed, not agreeable but necessary, and I tossed the cigar stump out of the window. But what I determined to do, may seem no great thing after all; it was only to paint the portrait of my landlady.

“Yes, I’ll paint the old wench!”

Now, I am an artist, not an author, and have got the cart before the horse, inasmuch as my narrative does not preserve the “harmonies,” as every well-considered composition should do. It has just occurred to me that I should first have[16] told who I am, and how I came to be in Jamaica, and especially in that filthy place, Kingston. It isn’t a long story, and if it is not too late, I will tell it now.

As all the world knows, there are people who sell rancid whale oil, and deal in soap, and affect a great contempt for artists. They look down grandly on the quiet, pale men who paint their broad red faces on canvas, and seem to think that the few greasy dollars which they grudgingly pay for their flaming immortality, should be received with meek confusion and blushing thanks, as a rare exhibition of condescension and patronage. I never liked such patronage, and therefore would paint no red faces. But there is a great difference between red, bulbous faces, and rosy faces. There was that sweet girl at the boarding-school in L—— Place, the Baltimore girl, with the dark eyes and tresses of the South, and the fair cheek and elastic step of the North! Of course, I painted her portrait, a dozen times at least, I should say. I could paint it now; and I fear it is more than painted on my heart, or it wouldn’t rise smiling here, to distract my thoughts, make me sigh, and stop my story.

An artist who wouldn’t paint portraits and had a soul above patronage—what was there for him to do in New York? Two compositions a year in the Art Union, got in through Mr. Sly, the manager, and a friend of mine, were not an adequate support for the most moderate man. I’ll paint grand historical paintings, thought I one day, and straightway[17] purchased a large canvas. I had selected my subject, Balboa, the discoverer of the Pacific, bearing aloft the flag of Spain, rushing breast-deep in its waves, and claiming its boundless shores and numberless islands for the crown of Castile and Leon. I had begun to sketch in the plumed Indians, gazing in mute surprise upon this startling scene, when it occurred to me—for I have patches of common sense scattered amongst the flowery fields of my fancy—to count over the amount of my patrimonial portion. Grand historical paintings require years of study and labor, and I found I had but two hundred dollars, owed for a month’s lodging, and had an unsettled tailor’s account. It was clear that historical painting was a luxury, for the present at least, beyond my reach. It was then some evil spirit, (I strongly suspect it was the ——,) taking the cue doubtless from my projected picture, suggested:—

“Try landscape, my boy; you have a rare hand for landscapes—good flaming landscapes, full of yellow and vermillion, you know!”

Although there was no one in the room, I can swear to a distinct slap on the back, after the emphatic “you know” of the tempter. It was a true diabolical suggestion, the yellow and vermillion, but not so sulphurous as what followed:—

“Go to the tropics boy, the glorious tropics, where the sun is supreme, and never shares his dominion with blue-nosed, leaden-colored, rheumy-eyed frost-gods; go there, and catch the matchless[18] tints of the skies, the living emerald of the forests, and the light-giving azure of the waters; go where the birds are rainbow-hued, and the very fish are golden; where—”

But I had heard enough; I was blinded by the dazzling panorama which Fancy swept past my vision, and cried, with enthusiastic energy,

“Hold; I’ll go to the glorious tropics!”

And I went—more’s the pity—in a little dirty schooner, full of pork and flour; and that is the way I came to be in Jamaica, dear reader, if you want to know. I had been there a month or more, and had wandered all over the really magnificent interior, and filled my portfolio with sketches. But that did not satisfy me; there were other tropical lands, where Nature had grander aspects, where there were broad lakes and high and snow-crowned volcanoes, which waved their plumes of smoke in mid-heaven, defiantly, in the very face of the sun; lands through whose ever-leaved forests Cortez, Balboa, and Alvarado, and Cordova had led their mailed followers, and in whose depths frowned the strange gods of aboriginal superstition, beside the deserted altars and unmarked graves of a departed and mysterious people. Jamaica was beautiful certainly, but I longed for what the transcendentalists call the sublimely-beautiful, or, in plain English, the combined sublime and beautiful—for, in short, an equatorial Switzerland. And, although Jamaica was fine in scenery, its dilapidated plantations, and filthy, lazy negroes, already more than half relapsed[19] into native and congenial barbarism, were repugnant to my American notions and tastes. They grinned around me, those negroes, when I ate, and scratched their heads over my paper when I drew. They followed me every where, like black jackals, and jabbered their incomprehensive lingo in my ears until they deafened me. And then their odor under tropical heats! Faugh! “’Twas rank, and smelt to heaven!”

I had, therefore, come down from the interior to set up my easel in Kingston, paint a few views, and thereby raise the wind for a trip to the mainland. Of course, I did not fly from painting red-faced portraits in the United States, to paint ebony ones in Jamaica. My scruples, however, did not apply to customers. There was a “brown man,” which is genteel Jamaican for mulatto, who was an Assembly-man, or something of the kind, and wanted a view of the edifice at Spanish-town, wherein he legislated for the “emancipated island.” I had agreed to paint it for the liberal compensation of twenty pounds. But one hot, murky morning, my brown lawgiver took the cholera, and before noon was not only dead, but buried—and my picture only half-finished! Mem. As people have a practice of dying, always get your pay beforehand.

Voltaire, I believe, has said, that if a toad were asked his ideal of beauty, he would, most likely, describe himself, and dwell complacently on a cold, clammy, yellow belly, a brown, warty, corrugated back, and become ecstatic on the subject of goggle[20] eyes. And, I verily believe, that if my landlady had been asked the same question, she would have coquettishly patted up her woolly curls over each oleaginous cheek, and glanced toward the mirror, by way of reply. Black, glossy black, and fat, marvelously fat, yet she was possessed, even she, of her full share of feminine vanity. There was no mistaking, from the first day of my arrival, that her head was running on a portrait of herself. She was fond of money and penurious, and careful, therefore, not to venture upon a proposition until she had got some kind of a clew as to what her immortality would be likely to cost. I had, however, diplomatically evaded all of her approaches, up to the unfortunate day when my Assembly-man died. She brought me the news herself, and saw that it annoyed rather than shocked me, and that I stopped painting with the air of a man abandoning a bad job. She evidently thought the time favorable for a coup de main; there was a gleam of cunning in her little, round, half-buried eyes, and the very ebony of her cheek lightened palpably, as she said:

“So your picture will be no good for nothing?”

No!

“You have not got the——?”

And she significantly rubbed the forefinger of one hand in the palm of the other.

No!

There was a pause, and then she resumed:

“I want a picture!”

Eh?

“A picture, you know!”

And now she complacently stroked down her broad face, and exhibited a wide, vermillion chasm, with a formidable phalanx of ivories, by way of a suggestive smile.

No, I never paint portraits!

“Not for ten pounds?”

No; nor for a hundred,—go!

And my landlady rolled herself out of the room with a motion which, had she weighed less than two hundred, might have passed for a toss.

It was on the evening of this day, and after this conversation, one half of the Assembly-house at Spanish-town staring redly from the canvas in the corner, that I lay in my hammock and soliloquized as aforesaid. It was thus and then, that I resolved to paint my landlady.

And having now, by means of this long parenthesis, restored the harmonies of my story, and got my horse and cart in correct relative positions, I am ready to go ahead.

I not only resolved to paint my landlady, but I did it, right over the half-finished Assembly-house. It was the first, and, by the blessing of Heaven, so long as there are good potatoes to be dug at the rate of six cents the bushel, it shall be my last portrait. I can not help laughing, even now, at that fat, glistening face, looking for all the world as if it had been newly varnished, surmounted by a[22] gaudy red scarf, wound round the head in the form of a peaked turban; and two fat arms, rolling down like elephants’ trunks against a white robe for a background, which concealed a bust that passeth description. That portrait—“long may it wave!” as the man said, at the Kossuth dinner, when he toasted “The day we celebrate!”

MY LANDLADY.

My landlady was satisfied, and generous withal, for she not only paid me the ten pounds, and gave me my two weeks board and lodging in the bargain, but introduced me to a colored gentleman, a friend of hers, who sailed a little schooner twice a year to the Mosquito Shore, on the coast of Central America, where he traded off refuse rum and gaudy cottons for turtle-shells and sarsaparilla. There was a steamer from Kingston, once a month, to Carthagena, Chagres, San Juan, Belize, and “along[23] shore;” but, for obvious reasons, I could not go in a steamer. So I struck up a bargain with the fragrant skipper, by the terms of which he bound himself to land me, bag and baggage, at Bluefields, the seat of Mosquito royalty, for the sum of three pounds, “currency.”

Why Captain Ponto (for so I shall call my landlady’s friend, the colored skipper) named his little schooner the “Prince Albert,” I can not imagine, unless he thought thereby to do honor to the Queen-Consort; for the aforesaid schooner had evidently got old, and been condemned, long before that lucky Dutchman woke the echoes of Gotha with his baby cries. The “Prince Albert” was of about seventy tons burden, built something on the model of the “Jung-frau,” the first vessel of the Netherlands that rolled itself into New York bay, like some unwieldy porpoise, after a rapid passage of about six months from the Hague. The wise men of the Historical Society have satisfactorily shown, after long and diligent research, that the “Jung-frau” measured sixty feet keel, sixty feet beam, and sixty feet hold, and was modeled after one of Rubens’ Venuses. The dimensions of the “Prince Albert” were every way the same, only twenty feet less. The sails were patched and the cordage spliced, and she did not leak so badly as to require more than six hours’ steady pumping out of the twenty-four. The crew was composed of Captain Ponto, Thomas, his mate, one seaman, and an Indian[24] boy from Yucatan, whose business it was to cook and do the pumping. As may be supposed, the Indian boy did not rust for want of occupation.

It was a clear morning, toward the close of December, that Captain Ponto’s wife, a white woman, with a hopeful family of six children, the three eldest with shirts, and the three youngest without, came down to the schooner to see us off. I watched the parting over the after-bulwarks, and observed the tears roll down Mrs. Ponto’s cheeks as she bade her sable spouse good-by. I wondered if she really could have any attachment for her husband, and if custom and association had utterly worn away the natural and instinctive repugnance which exists between the superior and inferior races of mankind? I thought of the condition of Jamaica itself, and mentally inquired if it were not due to a grand, practical misconception of the laws of Nature, and the inevitable result of their reversal? It can not be denied that where the superior and inferior races are brought in contact, and amalgamate, there we uniformly find a hybrid stock springing up, with most, if not all of the vices, and few, if any of the virtues of the originals. And it will hardly be questioned, by those experimentally acquainted with the subject, that the manifest lack of public morality and private virtue, in the Spanish-American States, has followed from the fatal facility with which the Spanish colonists have intermixed with the negroes and Indians. The rigid and inexorable exclusion, in respect[25] to the inferior races, of the dominant blood of North America, flowing through different channels perhaps, yet from the same great Teutonic source, is one grand secret of its vitality, and the best safeguard of its permanent ascendency.

Mrs. Ponto wept; and as we slowly worked our way outside of Port Royal, I could see her waving her apron, for she was innocent of a more classical signal, in fond adieus. We finally got out from under the lee of the land, and caught in our sails the full trade-wind, blowing steadily in the desired direction. I sat long on deck, watching the receding island sinking slowly in the bright sea, until Captain Ponto signified to me, in the patois of Jamaica, which the deluded people flatter themselves is English, that dinner was ready, and led the way into what he called the cabin. This cabin was a little den, seven feet by nine at the utmost, low, dark and dirty, with no light or air except what entered through the narrow hatchway, and, consequently, hot as an oven. Two lockers, one on each side, answered for seats by day, and, covered with suspicious mattresses, for beds by night. The cabin was sacred to Captain Ponto and myself, the mate having been displaced to make room for the gentleman who had paid three pounds for his passage! I question if the “Prince Albert” had ever before been honored with a passenger; certainly not since she had come into the hands of Captain Ponto, who therefore put his best foot forward, with a full consciousness of the importance of the incident.[26] Ponto had been a slave once, and was consequently imperious and tyrannical now, toward all people in a subordinate relation to himself. Yet, as he had evidently been owned by a man of consequence, he had not entirely lost his early deference for the white man, and sometimes forgot Ponto the captain in Ponto the chattel. It was in the latter character only, that he was perfectly natural; and, although I derived no little amusement from his attempts to enact a loftier part, I shall not trouble the reader with an episode on Captain Ponto. He was a very worthy darkey, with a strong aversion to water, both exteriorly and internally. The mate, and the man who constituted the crew, were ordinary negroes of no possible account.

But Antonio, the Indian boy, who cooked and pumped, and then pumped and cooked—I fear he never slept, for when there was not a “sizzling” in the little black caboose, there was sure to be a screeching of the rickety pump—Antonio attracted my interest from the first; and it was increased when I found that he spoke a little English, was perfect in Spanish, and withal could read in both languages. There was something mysterious in finding him among these uncouth negroes, with his relatively fair skin, intelligent eyes, and long, well-ordered, black hair. He was like a lithe panther among lumbering bears; and he did his work in a way which accorded with his Indian character, without murmur, and with a kind[27] of silent doggedness, that implied but little respect for his present masters. He seldom replied to their orders in words, and then only in monosyllables. I asked Captain Ponto about him, but he knew nothing, except that he was from Yucatan, and had presented himself on board only the day previously, and offered to work his passage to the main land. And Captain Ponto indistinctly intimated that he had taken the boy solely on my account, which, of course, led to the inference on my part, that the captain ordinarily did his own cooking. He also ventured a patronizing remark about the Indians generally, to the effect that they made very good servants, “if they were kept under;” which, coming from an ex-slave, I thought rather good.

ANTONIO.

All this only served to interest me the more in Antonio; and, although I succeeded in engaging him in ordinary conversation, yet I utterly failed in drawing him out, as the saying is, in respect to his past history, or future purposes. Whenever I approached these subjects he became silent and impassible, and his eyes assumed an expression of cold inquiry, not unmingled with latent suspicion, which half inclined me to believe that he was a fugitive from justice. Yet he did not look the felon or knave; and when the personal inquiries dropped, his face resumed its usual pleasant although sad expression, and I became ashamed that I had suspected him. There was certainly something singular about Antonio; but, as I could imagine no[28] very profound mystery attaching to a cook, on board of the “Prince Albert,” after the first day, I made no attempts to penetrate his secrets, but sought rather to attach him to me, as a prospectively useful companion in the country to which I was bound. So I relieved him occasionally at the pump, although he protested against it; and finally, to the horror of Captain Ponto, and the palpable high disdain of the mate, I became so intimate with him as to show him my portfolio of drawings. His admiration, I found to my surprise, was always judiciously bestowed, and his appreciation of outline and coloring showed that he had the spirit of an artist. Several times, in glancing[29] over the drawings, he stopped short, looked up, his face full of intelligence, as if about to speak, and I paused to listen. Each time, however, the smile vanished, the flexible muscles ceased their play and became rigid, and a cold, filmy mist settled over the clear eyes which had looked into mine. Whatever was Antonio’s secret, great or small, it was evidently one that he half-wished, half-feared to reveal. I was puzzled to think that there could exist any relation between it and my paintings; but Antonio was only a cook, and so I dismissed all reflection on the subject.

On our third day out, the weather, which up to that time had been clear and beautiful, began to change, and night settled black and threatening around us. The wind had increased, but it was loaded with sultry vapors—the hot breath of the storm which was pressing on our track. Captain Ponto was not a scientific sailor, and kept no other than what is called “dead reckoning.” He had made the voyage very often, and was confident of his course. Upon that point, therefore, I gave myself no uneasiness; not so much from faith in Captain Ponto, as because there was nothing in the world to be done, except to follow his opinion. Nevertheless the captain was serious, and consulted an antediluvian chart which he kept in his cabin. It was a Rembrandtish picture, that negro tracing his forefinger slowly over the chart, by the light of a candle, which only half revealed the little cabin, while it brought out his grizzly head and anxious[30] face in strong relief against the darkness. What Captain Ponto learned from all this study is more than I can tell; but when he came on deck, he ordered a reef to be made in the sails, and a variation of several points in our course, for the wind not only freshened, but veered to the north-east. The hot blasts or puffs of air became more and more frequent, and occasional sheets of lightning gleamed along the horizon. The sea, too, was full of phosphorescent light; fiery monsters seemed to leap around us and wreath and twine their livid volumes in our wake. I could hear the hiss of their forked tongues where the waters closed under our stern. I stood, leaning over the bulwarks, gazing on the gleaming waves, and thinking of home—for the voyager on the great deep always thinks of home, when darkness envelops him, and the storm threatens—when Antonio silently approached, so silently that I did not hear him, and took his place at my side. I was somewhat startled, therefore, when, changing my position a little, I saw, by the dim, reflected light of the sea, his eyes fixed earnestly on mine. “Ah, Antonio,” I said, “is that you?” and I placed my hand familiarly on his shoulder. He shrank beneath it, as if it had been fire. “What’s the matter?” I exclaimed, reproachfully; “have I hurt you?”

“Pardon me!” he ejaculated, rather than spoke, in a voice deep and tremulous; “I know now that it is not you who will die to-night!”

“What do you mean? You are not afraid, Antonio?[31] Who thinks of dying?” I replied, in a light tone.

“No! it is not myself. I was afraid it might be you; for, sir,” and he laid a hand cold and clammy as that of a corpse on mine; “for, sir, there is death on board this vessel!”

This was said in a voice so awed and earnest that I was impressed deeply, in spite of myself, and for some moments made no reply. “You talk wildly, Antonio,” I finally said; “we are going on bravely, and shall all be in Bluefields together in a day or two.”

“All of us, never,” he replied, “never! The Lord, who never lies, has told me so!” and, pressing near me, he drew from his bosom something resembling a small, round plate of crystal, except that it seemed to be slightly luminous, and veined or clouded with green. “See, see!” he exclaimed, rapidly, and held the object close to my eyes. I instinctively obeyed, and gazed intently upon it. As I gazed, the clouds of green seemed to concentrate and assume a regular form, as the moisture of one’s breath passes away from a mirror, until I distinctly saw, in the center, the miniature of a human head, of composed and dignified aspect, but the eyes were closed, and all the lineaments had the rigidity of death.

“Do you see?”

“I do!”

“It is Kucimen, the Lord who never lies!” and Antonio thrust his talisman in his bosom again,[32] and slowly moved away. There was no mistake in what I had seen, and although I am not superstitious, yet the feeling that some catastrophe was impending gathered at my heart. It was in vain that I tried to smile at the Indian trick; the earnest voice of the Indian boy still sounded in my ears, “All of us, never!” What reason should he have for attempting to practice his Indian diablerie on any one, least of all on me? I rejected the thought, and endeavored to banish the subject from my mind.

Meanwhile the wind had gathered strength, and Captain Ponto had taken in sail, so that we had no more standing than was necessary to keep the vessel steady before the wind. The waves now began to rise, the gloom deepened, the hot puffs of air became more and more frequent, and the broad lightning-sheets rose from the horizon to the very zenith. The thunder, too, came rolling on, every peal more distinctly, and occasional heavy drops of rain fell with an ominous sound on the deck. The storm was evidently close at hand; and I left the side of the vessel, and approached the little cabin to procure my poncho, for I preferred the open deck and the storm to the suffocation below. The hatchway was nearly closed, but there was a light within. I stooped to remove the slide, and in doing so obtained a full view of the interior. The spectacle which presented itself was so extraordinary that I stopped short, and looked on in mute surprise. The candle was standing on the locker, and kneeling[33] beside it was the captain. He was stripped to the waist, and held in one hand what appeared to be the horn of some animal, in which he caught the blood which dripped from a large gash in the fleshy part of his left arm, just above the elbow, while he muttered rapidly some rude and strangely-sounding words, unlike any I had ever before heard. My first impression was that Antonio had tried to fulfill his own prediction, by attempting the life of the captain; but I soon saw that he was performing some religious rite, a sacrifice or propitiation, such as the Obi men still teach in Jamaica and Santo Domingo, and which are stealthily observed, even by the negroes professing Christianity and having a nominal connection with the church. I recognized in the horn the mysterious gre-gre of the Gold Coast, where the lowest form of fetish worship prevails, and where human blood is regarded as the most acceptable of sacrifices. Respecting too rigidly all ceremonies and rites, which may contribute to the peace of mind of others, to think of disturbing them, I silently withdrew from the hatchway, and left the captain to finish his debasing devotions. In a short time he appeared on deck, and gave some orders in a calm voice, as one reassured and confident.

I was occupied below for only a few minutes, yet when I got on deck again the storm was upon us. The waves were not high, but the water seemed to be caught up by the wind, and to be drifted along, like snow, in blinding, drenching sheets. I was nearly driven off my feet by its[34] force, and would have been carried overboard had I not become entangled in the rigging. The howling of the wind and the hissing of the water would have drowned the loudest voice, and I was so blinded by the spray that I could not see. Yet I could feel that we were driving before the hurricane with fearful rapidity. The very deck seemed to bend, as if ready to break, beneath our feet. I finally sufficiently recovered myself to be able, in the pauses of the wind, and when the lightning fell, to catch glimpses around me. Our sails were torn in tatters, the yards were gone, in fact every thing was swept from the deck except three dark figures, like myself, clinging convulsively to the ropes. On, on, half-buried in the sea, we drifted with inconceivable rapidity.

Little did we think that we were rushing on a danger more terrible than the ocean. The storm had buffeted us for more than an hour, and it seemed as if it had exhausted its wrath, and had begun to subside, when a sound, hoarse and steady, but louder even than that of the wind, broke on our ears. It was evident that we were approaching it, for every instant it became more distinct and ominous. I gazed ahead into the hopeless darkness, when suddenly a broad sheet of lightning revealed immediately before us, and not a cable’s length distant, what, under the lurid gleam, appeared to be a wall of white spray, dashing literally a hundred feet in the air—a hell of waters, from which there was no escape. “El Roncador!” shrieked the[35] captain, in a voice of utter despair, that even then thrilled like a knife in my heart. The fearful moment of death had come, and I had barely time to draw a full breath of preparation for the struggle, when we were literally whelmed in the raging waters. I felt a shock, a sharp jerk, and the hiss and gurgle of the sea, a sensation of immense pressure, followed by a blow like that of a heavy fall. Again I was lifted up, and again struck down, but this time with less force. I had just enough consciousness left to know that I was striking on the sand, and I made an involuntary effort to rise and escape from the waves. Before I could gain my feet I was again struck down, again and again, until, nearer dead than alive, I at last succeeded in crawling to a spot where the water did not reach me. I strove to rise now, but could not; and, as that is the last thing I remember distinctly of that terrible night, I suppose I must have fallen into a swoon.

THE SHIPWRECK.

How long I remained insensible I know not, but when my consciousness returned, which it did slowly, like the lifting of a curtain, I felt that I was severely hurt; and, before opening my eyes, tried to drive away my terrible recollections, as one rousing from a troubled dream tries to banish its features from his mind. It was in vain; and, with a sensation of despair, I opened my eyes! The morning sun was shining with blinding brilliancy, and I was obliged to close them again. Soon, however, I was able to bear the blaze, and, painfully lifting myself on my elbow, looked around me. The sea was thundering with awful force, not on the sandy shore where I was lying, but over a reef two hundred yards distant, within which the water was calm, or only disturbed by the combing waves, as they broke over the outer barrier. Here[37] the first and only object which attracted my attention was our schooner, lying on her beam ends, high on the sands. The sea, the vessel, the blinding sun and glowing sand, and a bursting pain in my head, were too palpable evidences of my misfortune to be mistaken. It was no dream, but stern and severe reality, and for the moment I comprehended the truth. But, when younger, I had read of shipwrecks, and listened, with the interest of childhood, and a feeling half of envy, to the tales of old sailors who had been cast away on desert shores. And now, the first shock over, it was almost with a sensation of satisfaction, and something of exultation, that I exclaimed to myself, “shipwrecked at last!” Robinson Crusoe, and Reilly and his companions, recurred to my mind, and my impulse was to leap up and commence an emulative career. But the attempt was a failure, and brought me back to stern reality, in an instant. My limbs were torn and scarified, and my face swollen and stiff. The utmost I could do was to sit erect.

I now, for the first time, thought of my companions, and despairingly turned my eyes to look for them. Close by, and nearly behind me, sat Antonio, resting his head on his hands. His clothes were hanging around him in shreds, his hair was matted with sand, and his face was black with dried blood. He attempted to smile, but the grim muscles could not obey, and he looked at me in silence. I was the first to speak:

Are you much hurt, Antonio?

“The Lord of Mitnal never lies!” was his only response; and he pointed to the talisman on his swarthy breast, gleaming like polished silver in the sun. I remembered the scene of the previous night, and asked;—

Are they all dead?

He shook his head, in sign of ignorance.

Where are we, Antonio?

“This is El Roncador!”

And so it proved. We were on one of the numerous coral keys or cays which stud the sea of the Antilles, and which are the terror of the mariners who navigate it. They are usually mere banks of sand, elevated a few feet above the water, occasionally supporting a few bushes, or a scrubby, tempest-twisted palm or two, and only frequented by the sea-birds for rest and incubation, and by turtles for laying their eggs. Around them there is always a reef of coral, built up from the bottom of the sea by those wonderful architects, the coral insects. This reef surrounds the cay, at a greater or less distance, like a ring, leaving between it and the island proper a belt of water, of variable depth, and of the loveliest blue. The reef, which is sometimes scarcely visible above the sea, effectually breaks the force of the waves; and if, as it sometimes happens, it be interrupted so as to leave an opening for the admission of vessels, the inner belt of water forms a safe harbor. Except a few of the larger ones, none of these cays are inhabited, nor are they ever frequented, except by the turtle fishers.

It was to the peculiar conformation of these islands that our safety was owing. Our little vessel had been driven, or lifted by the waves, completely over the outer reef. The shock had torn us from our hold on the ropes, and we had drifted upon the comparatively protected sands. The vessel too, had been carried upon them, and the waves there not being sufficiently strong to break her in pieces, she was left high and dry when they subsided. There was, nevertheless, a broad break in her keel, caused probably by striking on the reef.

Two of the five human beings who had been on board of her, the captain and his mate, were drowned. We found their bodies;—but I am anticipating my story. When we had recovered ourselves sufficiently to walk, Antonio and myself took a survey of our condition. “El Roncador,” the Snorer, is a small cay, three quarters of a mile long, and at its widest part not more than four hundred yards broad,—a mere bank of white sand. At the eastern end is an acre or more of scrubby bushes, and near them three or four low and distorted palm-trees. Fortunately for us, as will be seen in the sequel, “El Roncador” is famous for the number of its turtles, and is frequented, at the turtle season, by turtle-fishers from Old Providence, and sometimes from the main land. Among the palm-trees, to which I have referred, these fishermen had erected a rude hut of poles, boards, and palm-branches, which was literally withed and anchored to the trees, to keep it from being blown away by[40] the high winds. It was with a heart full of joy that I saw even this rude evidence of human intelligence, and, accompanied by Antonio, hastened to it as rapidly as my bruised limbs would enable me. We discovered no trace of recent occupation as we approached, except a kind of furrow in the sand, like that which some sea-monster, dragging itself along, might occasion. It led directly to the hut, and I followed it, with a feeling half of wonder, half of apprehension. As we came near, however, I saw, through the open front, a black human figure crouching within, motionless as a piece of bronze. Before it, stretched at length, was the dead body of Captain Ponto. The man was Frank, of whom I have spoken, as constituting the crew of the Prince Albert. It was a fearful sight! The body of the captain was swollen, the limbs were stiff and spread apart, the mouth and eyes open, and conveying an expression of terror and utter despair, which makes me shudder, even now, when I think of it. Upon his breast, fastened by a strong cord, drawn close at the throat, was the mysterious gre-gre horn, and the gash in his arm, from which the poor wretch had drawn the blood for his unavailing sacrifice, had opened wide its white edges, as if in mute appeal against his fate.

The negro sailor had drawn the body of the captain to the hut, and the trail in the sand was that which it had made. I spoke to him, but he neither replied nor looked up. His eyes were fixed, as if by some fascination, on the corpse. Antonio[41] exhibited no emotion, but advancing close to the body lifted the gre-gre horn, eyed it curiously for a moment, then tossed it contemptuously aside, exclaiming:—

“It could not save him: it is not good!”

The words were scarcely uttered, when the crouching negro leaped, like a wild beast, at the Indian’s throat; but Antonio was agile, and evaded his grasp. The next instant the poor wretch had returned to his seat beside the dead. The negro could not endure a sneer at the potency of the gre-gre. Such is the hold of superstition on the human mind!

I tried to induce the negro to remove the body, and bury it in the sand; but he remained silent and impassible as a stone. So I returned with Antonio to the vessel, for the instincts of life had come back. We found, although the little schooner had been completely filled, that the water had escaped, and left the cargo damaged, but entire. Some of the provisions had been destroyed, and the remainder was much injured. Nevertheless they could be used, and for the time being, at least, we were safe from starvation. My spirits rose with the discovery, and I almost forgot my injuries in the joy of the moment. But Antonio betrayed no signs of interest. He lifted boxes and barrels, and placed them on the sands, as deliberately as if unloading the vessel at Kingston. I knew that it was not probable the wrecked schooner would suffer further damage from the sea, protected as it was[42] by the outer reef, yet I sought to make assurance doubly sure, by removing what remained of the provisions to the hut by the palm-trees. Antonio suggested nothing, but implicitly followed my directions.

We had got out most of the stores, and carried them above the reach of the waters on the sands, when I went back to the hut, with the determination, by at once assuming a tone of authority, to have the negro remove and bury the body of the captain. I was surprised to find the hut empty, and a trail, like that which had attracted my notice in the morning, leading off in the direction of the bushes, at some distance from the hut. I followed it; and, in the centre of the clump, discovered the negro filling in the sand above the corpse. He mumbled constantly strange guttural words, and made many mysterious signs on the sand, as he proceeded. When the hole was entirely filled, he laid himself at length above it. I waited some minutes, but as he remained motionless, returned to the hut. We now commenced carrying to it, such articles of use as could be easily removed. But we had not accomplished much when Frank, the negro, presented himself; and, approaching me, inquired meekly what he should do. He was least injured of the three, and proved most serviceable in clearing the wreck of all of its useful and moveable contents.

By night I had bandaged my own wounds and those of my companions, and over a simple but[43] profuse meal, forgot the horrors of the shipwreck, and gave myself up, with real zest, to the pleasures of a cast-away! I cannot well describe the sensation of mingled novelty and satisfaction, with which I looked out from the open hut upon the turbulent waters, whence we had so narrowly escaped. The sea still heaved from the effects of the storm, but the storm itself had passed, and the full tropical moon looked down calmly upon our island, which seemed silvery and fairy-like beneath its rays.

At first, all these things were quieting in their influences, but as the night advanced I must have become feverish, for notwithstanding the toils of the day, and the exhaustion of the previous night, I could not sleep. My thoughts were never so active. All that I had ever seen, heard, or done, flashed back upon my mind with the vividness of reality. But, owing to some curious psychical condition, my mind was only retrospectively active; I tried in vain to bring it to a contemplation of the present or the future. Incidents long forgotten jostled through my brain; the grave mingling strangely with the gay. Now I laughed outright over some freak of childhood, which came back with primitive freshness; and, next moment, wept again beside the bed of death, or found myself singing some hitherto unremembered nursery rhyme. I struggled against these thronging memories, and tried to ask myself if they might not be premonitions of delirium. I felt my own pulse, it beat rapidly; my own forehead, and it seemed to burn. In the vague hope of[44] averting whatever this strange mental activity might portend, I rose and walked down to the edge of the water. I remember distinctly that the shore seemed black with turtles, and that I thought them creations of a disordered fancy, and became almost mad under the mere apprehension that the madness was upon me.

I might, and undoubtedly would, have become mad, had it not been for Antonio. He had missed me from the hut; and, in alarm, had come to seek me. I felt greatly relieved when he told me that there were real turtles on the shore, and not monsters of the imagination; and that it was now the season for laying their eggs, and therefore it could not be long before the fishers would come for their annual supply of shells. So I suffered him to lead me back to the hut. When I laid down he took my head between his hands, and pressed it steadily, but apparently with all his force. The effect was soothing, for in less than half an hour my ideas had recovered their equilibrium, and I fell into a slumber, and slept soundly until noon of the following day.

When I awoke, Antonio was sitting close by me, and intently watching every movement. He smiled when my eyes met his, and pointing to his forehead said significantly—

“It is all right now!”

And it was all right, but I felt weak and feverish still. A sound constitution, however, resisted all attacks, and it was not many days before I was able[45] to move around our sandy prison, and join Antonio and Frank in catching turtles; for, with more foresight than I had supposed to belong to the Indian and negro character, they were laying in a stock of shells, against the time when we should find an opportunity of escape. Upon the side of our island, to which I have alluded as covered with bushes, the water was comparatively shoal, and the bottom overgrown with a species of sea-grass, which is a principal article of turtle-food. The surface of the water, also, was covered with a variety of small blubber fish, which Antonio called by the Spanish name of dedales, or thimbles—a name not inappropriate, since they closely resembled a lady’s thimble both in shape and size. These, at the spawning or egg-laying period of the year, constitute another article of turtle-food. During the night-time the turtles crawled up on the shore, and the females dug holes in the sand, each about two feet deep, in which they deposited from sixty to eighty eggs. These they contrived to cover so neatly, as to defy the curiosity of one unacquainted with their habits. Both Antonio and Frank, however, were familiar with turtle-craft, and got as many eggs as we desired. When roasted, they are really delicious. The Indians and people of the coasts never destroy them, being careful to promote the increase of this valuable shell-fish. But on the main land, wild animals, such for instance as the cougar, frequently come down to the shore, and dig them from their resting places. Occasionally they capture the turtles[46] themselves, and dragging them into the forest, kill and devour them, in spite of their shelly armor.

“SHELLING” TURTLES.

It was during the night, therefore, that Antonio and Frank, who kept themselves concealed in the bushes, rushed out upon the turtles, and with iron hooks turned them on their backs, when they became powerless and incapable of moving. The day following, they dragged them to the most distant part of the island, where they “shelled” them;—a cruel process, which it made my flesh creep to witness. Before describing it, however, I must explain that, although the habits of all varieties of the turtle are much the same, yet their uses are very different. The large, green turtle is best known; it frequently reaches our markets, and its flesh is esteemed, by epicures, as a great delicacy.[47] The flesh of the smaller or hawk-bill variety is not so good, but its shell is most valuable, being both thicker and better-colored. What is called tortoise-shell is not, as is generally supposed, the bony covering or shield of the turtle, but only the scales which cover it. These are thirteen in number, eight of them flat, and five a little curved. Of the flat ones four are large, being sometimes a foot long and seven inches broad, semi-transparent, elegantly variegated with white, red, yellow, and dark brown clouds, which are fully brought out, when the shell is prepared and polished. These laminæ, as I have said, constitute the external coating of the solid or bony part of the shell; and a large turtle affords about eight pounds of them, the plates varying from an eighth to a quarter of an inch in thickness.

The fishers do not kill the turtles; did they do so, they would in a few years exterminate them. When the turtle is caught, they fasten him, and cover his back with dry leaves or grass, to which they set fire. The heat causes the plates to separate at their joints. A large knife is then carefully inserted horizontally beneath them, and the laminæ lifted from the back, care being taken not to injure the shell by too much heat, nor to force it off, until the heat has fully prepared it for separation. Many turtles die under this cruel operation, but instances are numerous in which they have been caught a second time, with the outer coating reproduced; but, in these cases, instead of thirteen[48] pieces, it is a single piece. As I have already said, I could never bring myself to witness this cruelty more than once, and was glad that the process of “scaling” was carried on out of sight of the hut. Had the poor turtles the power of shrieking, they would have made that barren island a very hell, with their cries of torture.

A SAIL! A SAIL!

We had been nearly two weeks on the island, when we were one morning surprised by a sail on the edge of the horizon. We watched it eagerly, and as it grew more and more distinct, our spirits rose in proportion. Its approach was slow, but at noon Frank declared that it was a turtle schooner, from the island of Catarina or Providence, and that it was making for “El Roncador.” And the event proved that he was right; for, about the middle of the afternoon, she had passed an opening through the reef, and anchored in the still water inside. She had a crew of five men, in whom it was difficult to say if white, negro, or Indian blood predominated. They spoke a kind of patois, in which Spanish was the leading element. And although we were unqualifiedly[49] glad to see them, yet they were clearly not pleased to see us. The patrón, or captain, no sooner put his foot on shore, than affecting to regard us as intruders, he demanded why we were there? and if we did not know that this island was the property of the people of Catarina? We replied by pointing to our shattered schooner, when the whole party started for it, and unceremoniously began to strip it of whatever article of use or value they could find, leaving us to the pleasant reflections which such conduct was likely to suggest.

While this was going on, I returned to the hut, and found that Antonio and Frank had already removed the shells which they had procured, as also some other valuables which we had recovered from the wreck, and had buried them in the sand—a prudent precaution, which no doubt saved us much trouble. A little before sundown, our new friends, having apparently exhausted the plunder, came trooping back to the hut, and without ceremony ordered us out. I thought, although the physical force was against us, that a little determination might make up for the odds, and firmly replied that they might have a part of it, if they wished, but that we were there, and intended to remain. The patron hereupon fell into a great passion, and told his men to bring up the machétes—ugly instruments, half knife, half cleaver. “He would see,” he said, in his mongrel tongue, “if this white villain would refuse to obey him.” Two of the men started to fulfill his order, while he stood scowling[50] in the doorway. When they had got off a little distance, I unrolled a blanket in which I had wrapped our pistols, and giving one to Frank, and another to Antonio, I took my own revolver, and passed outside of the hut. The patron fell back, in evident alarm.

“Now, amigo,” said I, “if you want a fight, you shall have it; but you shall die first!” And I took deliberate aim at his breast, at a distance of less than five yards. “Mother of Mercy!” he exclaimed, and glanced round, as if for support, to his followers. But they had taken to their legs, without waiting for further proceedings. The patron attempted to follow, but I caught him by the arm, and pressed the cold muzzle of the pistol to his head. He trembled like an aspen, and sunk upon the ground, crying in most abject tones for mercy. I released him, but he did not attempt to stir. The circumstances were favorable for negotiation, and in a few minutes it was arranged that we should continue to occupy the hut, and that he should remain with us, while his crew should stay on board the vessel, when not engaged in catching turtles. He did not like the exception in his favor; but, fearing that he might pull up anchor and leave us to our fate, I insisted that I could not forego the pleasure of his company.

The reader may be sure that I had a vigilant eye on our patron, and at night either Antonio or Frank kept watch, that he should not give us the slip. He made one or two attempts, but finding us[51] prepared, at the end of a couple of days, resigned himself to his fate. Contenting ourselves with our previous spoil, we allowed the new comers to pursue the fishery alone. At the end of a week I discovered, by various indications, that the season was nearly over, and, accordingly, making a careless display of my revolver, told the captain that I thought it would be more agreeable for us to go on board his schooner, than to remain on shore. I could see that the proposition was not acceptable, and therefore repeated it, in such a way that there was no alternative but assent left. He was a good deal surprised when he discovered the amount of shells which we had obtained; and when I told him that he should have half of it, for carrying us to Providence, and the whole if he took us to Bluefields, his good nature returned. He asked pardon for his rudeness, and, slapping his breast, proclaimed himself “un hombre bueno,” who would take us to the world’s end, if I would only put up my horrible pistol. That pistol, from the very first day, had had a kind of deadly fascination for the patron, who watched it, as if momentarily expecting it to discharge itself at his head. And even now, when he alluded to it, a perceptible shudder ran through his frame.

Two days after I had taken up my quarters on board of the little schooner, which, in age and accumulated filth, might have been twin-brother of the Prince Albert, we set sail from “El Roncador.” As it receded in the distance, it looked very beautiful—an[52] opal in the sea—and I could hardly realize that it was nothing more than a reef-girt heap of desert sands.

Although friendly relations had been restored with the patron, for the crew seemed nearly passive, I kept myself constantly on my guard against foul play. Antonio was sleeplessly vigilant. But the patron, so far from having evil designs, appeared really to have taken a liking to me, and expatiated upon the delights of Providence, where he represented himself as being a great man, with much uncouth eloquence. He promised that I should be well received, and that he would himself get up a dance—which he seemed to think the height of civility—in my honor.

“EL RONCADOR.”

About noon, on our third day from “El Roncador,” the patron pointed out to me two light blue mounds, one sharp and conical, and the other round and broad, upon the edge of the horizon. They were the highlands of Providence. Before night, we had doubled the rocky headland of Santa Catarina, crowned with the ruins of some old Spanish fortifications, and in half an hour were at anchor,[53] alongside a large New Granadian schooner, in the small but snug harbor of the island.

This island is almost unknown to the world; it has, indeed, very little to commend it to notice. Although accounted a single island, it is, in fact, two islands; one is six or eight miles long, and four or five broad, and but moderately elevated; while the second, which is a rocky headland, called Catarina, is separated from the main body by a narrow but deep channel. The whole belongs to New Granada, and has about three hundred inhabitants, extremely variegated in color, but with a decided tendency to black. This island was a famous resort of the pirates, during their predominance in these parts, who expelled the Spaniards, and built defences, by means of which they several times repelled their assailants.

The productions consist chiefly of fruits and vegetables; a little cotton is also raised, which, with the turtle-shells collected by the inhabitants, constitutes about the only export of the island. Vessels coming northward sometimes stop there, for a cargo of cocoa-nuts and yucas.

As can readily be imagined, the people are very primitive in their habits, living chiefly in rude, thatched huts, and leading an indolent, tropical life, swinging in their hammocks and smoking by day, and dancing, to the twanging of guitars, by night. My patron, whom I had suspected of being something of a braggart, was in reality a very considerable personage in Providence, and I was received[54] with great favor by the people, to whom he introduced me as his own “very special friend.” I thought of our first interview on “El Roncador,” but suppressed my inclination to laugh, as well as I was able. True to his promise, the second night after our arrival was dedicated to a dance. The only preparation for it consisted in the production of a number of large wax candles, resembling torches in size, and the concoction of several big vessels of drink, in which Jamaica rum, some fresh juice of the sugar-cane, and a quantity of powdered peppers were the chief ingredients. The music consisted of a violin, two guitars and a queer Indian instrument, resembling a bow, the string of which, if the critic will pardon the bull, was a brass wire drawn tight by means of a perforated gourd, and beaten with a stick, held by the performer, between his thumb and forefinger.

I cannot attempt to describe the dance, which, not over delicate at the outset, became outrageous as the calabashes of liquor began to circulate. Both sexes drank and danced, until most could neither drink nor dance; and then, it seemed to me, they all got into a general quarrel, in which the musicians broke their respective instruments over each other’s heads, then cried, embraced, and were friends again. I did not wait for the end of the debauch, which soon ceased to be amusing; but, with Antonio, stole away, and paddled off to the little schooner, where the last sounds that rung in my ears were the shouts and discordant songs of the revelers.

Providence, it can easily be understood, offered few attractions to an artist minus the materials for pursuing his vocation; and I was delighted when I learned that the New Granadian schooner was on the eve of her departure for San Juan de Nicaragua. Her captain readily consented to land me at Bluefields, and our patron magnificently waived all claims to the tortoise-shells which we had obtained at “El Roncador.” I had no difficulty in selling them to the captain of “El General Bolivar” for the unexpected sum of three hundred dollars. Fifty dollars of these I gave to the negro Frank, who was quite at home in Providence. I offered to divide the rest with Antonio, but he refused to receive any portion of it, and insisted on accompanying me without recompense. “You are my brother,” said he, “and I will not leave you.” And here I may add that, in all my wanderings, he was my constant companion and firm and faithful friend. His history, a wild and wonderful tale, I shall some day lay before the world: for Antonio was of regal stock, the son and lieutenant of Chichen Pat, one of the last and bravest of the chiefs of Yucatan, who lost his life, under the very walls of Merida, in the last unsuccessful rising of the aborigines; and I blush to add that the fatal bullet, which slew the hope of the Indians, was sped from the rifle of an American mercenary!

The approach to the coast, near Bluefields, holds out no delusions. The shore is flat, and in all respects tame and uninteresting. A white line of sand, a green belt of trees, with no relief except here and there a solitary palm, and a few blue hills in the distance, are the only objects which are offered to the expectant eyes of the voyager. A nearer approach reveals a large lagoon, protected by a narrow belt of sand, covered, on the inner side, with a dense mass of mangrove trees; and this is the harbor of Bluefields. The entrance is narrow, but not difficult, at the foot of a high, rocky bluff, which completely commands the passage.

The town, or rather the collection of huts called by that name, lies nearly nine miles from the entrance. After much tacking, and backing, and filling, to avoid the innumerable banks and shallows[57] in the lagoon, we finally arrived at the anchorage. We had hardly got our anchor down, before we were boarded by a very pompous black man, dressed in a shirt of red check, pantaloons of white cotton cloth, and a glazed straw hat, with feet innocent of shoes, whose office nobody knew, further than that he was called “Admiral Rodney,” and was an important functionary in the “Mosquito Kingdom.” He bustled about, in an extraordinary way, but his final purpose seemed narrowed down to getting a dram, and pocketing a couple of dollars, slily slipped into his hand by the captain, just before he got over the side. When he had left, we were told that we could go on shore.

Bluefields is an imperial city, the residence of the court of the Mosquito Kingdom, and therefore merits a particular description. As I have said, it is a collection of the rudest possible thatched huts. Among them are two or three framed buildings, one of which is the residence of a Mr. Bell, an Englishman, with whom, as I afterwards learned, resided that world-renowned monarch, “George William Clarence, King of all the Mosquitos.” The site of the huts is picturesque, being upon comparatively high ground, at a point where a considerable stream from the interior enters the lagoon. There are two villages; the principal one, or Bluefields proper, which is much the largest, containing perhaps five hundred people; and “Carlsruhe,” a kind of dependency, so named by a colony of Prussians who had attempted to establish themselves here,[58] but whose colony, at the time of my visit, had utterly failed. Out of more than a hundred of the poor people, who had been induced to come here, but three or four were left, existing in a state of great debility and distress. Most of their companions had died, but a few had escaped to the interior, where they bear convincing witness to the wickedness of attempting to found colonies, from northern climates, on low, pestiferous shores, under the tropics.

Among the huts were many palm and plantain trees, with detached stalks of the papaya, laden with its large golden fruit. The shore was lined with canoes, pitpans and dories, hollowed from the trunks of trees, all sharp, trim, and graceful in shape. The natives propel them, with great rapidity, by single broad-bladed paddles, struck vertically in the water, first on one side, and then on the other.[1]

There was a large assemblage on the beach, when we landed, but I was amazed to find that, with few exceptions, they were all unmitigated negros, or Sambos (i. e. mixed negro and Indian). I had heard of the Mosquito shore as occupied by the Mosquito Indians, but soon found that there were[59] few, if any, pure Indians on the entire coast. The miserable people who go by that name are, in reality, Sambos, having a considerable intermixture of trader blood from Jamaica, with which island the coast has its principal relations. The arrival of the traders on the shore is the signal for unrestrained debauchery, always preluded by the traders baptizing, in a manner not remarkable for its delicacy or gravity, all children born since their last visit, in whom there is any decided indication of white blood. The names given on these occasions are as fantastic as the ceremony, and great liberties are taken with the cognomens of all notabilities, living and dead, from “Pompey” down to “Wellington.”

Our first concern in Bluefields was to get a roof to shelter us, which we finally succeeded in doing, through the intervention of the captain of the “Bolivar.” That is to say, a dilapidated negro from Jamaica, hearing that I had just left that delectable island, claimed me as his countryman, and gave me a little deserted thatched hut, the walls of which were composed of a kind of wicker work of upright canes, interwoven with palm leaves. This structure had served him, in the days of his prosperity, as a kitchen. It was not more than ten feet square, but would admit a hammock, hung diagonally from one corner to the other. To this abbreviated establishment, I moved my few damaged effects, and in the course of the day, completely domesticated myself. Antonio exhibited the greatest aptness and industry in making our quarters comfortable,[60] and evinced an elasticity and cheerfulness of manner unknown before. In the evening, he responded to the latent inquiry of my looks, by saying, that his heart had become lighter since he had reached the continent, and that his Lord gave promise of better days.

“Look!” he exclaimed, as he held up his talisman before my eyes. It emitted a pale light, which seemed to come from it in pulsations, or radiating circles. It may have been fancy, but if so, I am not prepared to say that all which we deem real is not a dream and a delusion!

My host was a man of more pretensions than Captain Ponto, but otherwise very much of the same order of African architecture. From his cautious silence, on the subject of his arrival on the coast, I inferred that he had been brought out as a slave, some thirty-five or forty years ago, when several planters from Jamaica attempted to establish themselves here. However that may have been, he now called himself a “merchant,” and appeared proud of a little collection of “osnaburgs,” a few red bandanna handkerchiefs, flanked by a dingy cask of what the Yankees would call “the rale critter,” which occupied one corner of his house or rather hut. He brooded over these with unremitting care, although I believe I was his only customer, (to the extent of a few fish hooks), during my stay in Bluefields. He called himself Hodgson, (the name, as I afterwards learned, of one of the old British superintendents,) and based his hopes[61] of family immortality upon a son, whom he respectfully called Mister James Hodgson, and who was, he said, principal counselor to the king. This information, communicated to me within two hours after my arrival, led me to believe myself in the line of favorable presentation at court. But I found out afterwards, that this promising scion of the house of Hodgson was “under a cloud,” and had lost the sunshine of imperial favor, in consequence of having made some most indiscreet confessions, when taken a prisoner, a few years before, by the Nicaraguans. However, I was not destined to pine away my days in devising plans to obtain an introduction to his Mosquito Majesty. For, rising early on the morning subsequent to my arrival, I started out to see the sights of Bluefields. Following a broad path, leading to a grove of cocoa-nut trees, which shadowed over the river, tall and trim, I met a white man, of thin and serious visage, who eyed me curiously for a moment, bowed slightly, and passed on in silence. The distant air of an Englishman, on meeting an American, is generally reciprocated by equally frigid formality. So I stared coldly, bowed stiffly, and also passed on. I smiled to think what a deal of affectation had been wasted on both sides, for it would have been unnatural if two white men were not glad to see each others’ faces in a land of ebony like this. So I involuntarily turned half round, just in time to witness a similar evolution on the part of my thin friend. It was evident that his thoughts were but reflections[62] of my own, and being the younger of the two, I retraced my steps, and approached him with a laughing “Good morning!” He responded to my salutation with an equally pregnant “Good morning,” at the same time raising his hand to his ear, in token of being hard of hearing. Conversation opened, and I at once found I was in the presence of a man of superior education, large experience, and altogether out of place in the Mosquito metropolis. After a long walk, in which we passed a rough board structure, surmounted by a stumpy pole, supporting a small flag—a sort of hybrid between the Union Jack and the “Stars and Stripes”—called by Mr. Bell the “House of Justice,” I accepted his invitation to accompany him home to coffee.

His house was a plain building of rough boards, with several small rooms, all opening into the principal apartment, in which I was invited to sit down. A sleepy-looking black girl, with an enormous shock of frizzled hair, was sweeping the floor, in a languid, mechanical way, calculated to superinduce yawning, even after a brisk morning walk. The partitions were hung with many prints, in which “Her Most Gracious Majesty” appeared in all the multiform glory of steel, lithograph, and chromotint. A gun or two, a table in the corner, supporting a confused collection of books and papers, with some ropes, boots, and iron grapnels beneath, a few chairs, a Yankee clock, and a table, completed the furniture and decoration of the room. I am thus particular[63] in this inventory, for reasons which will afterward appear.

At a word from Mr. Bell, the torpid black girl disappeared for a few moments, and then came back with some cups and a pot of coffee. I observed that there were three cups, and that my host filled them all, which I thought a little singular, since there were but two of us. A faint, momentary suspicion crossed my mind, that the female polypus stood in some such relation to my host as to warrant her in honoring us with her company. But, instead of doing so, she unceremoniously pushed open a door in the corner, and curtly ejaculated to some unseen occupant, “Get up!” There was a kind of querulous response, and directly a thumping and muttering, as of some person who regarded himself as unreasonably disturbed. Meanwhile we had each finished our first cup of coffee, and were proceeding with a second, when the door in the corner opened, and a black boy, or what an American would be apt to call, a “young darkey,” apparently nineteen or twenty years old, shuffled up to the table. He wore only a shirt, unbuttoned at the throat, and cotton pantaloons, scarcely buttoned at all. He nodded to my entertainer with a drawling “Mornin’, sir!” and sat down to the third cup of coffee. My host seemed to take no notice of him, and we continued our conversation. Soon after, the sloven youth got up, took his hat, and slowly walked down the path to the river, where I afterward saw him washing his face in the stream.

As I was about leaving, Mr. Bell kindly volunteered his services to me, in any way they might be made available. I thanked him, and suggested that, having no object to accomplish except to “scare up” adventures and seek out novel sights, I should be obliged to him for an introduction to the king, at some future day, after Antonio should have succeeded in rejuvenating my suit of ceremony, now rather rusty from saturation with salt water. He smiled faintly, and said, as for that matter, there need be no delay; and, stepping to the door, shouted to the black youth by the river, and beckoned to him to come up the bank. The youth put on his hat hurriedly, and obeyed. “Perhaps you are not aware that is the king?” observed my host, with a contemptuous smile. I made no reply, as the youth was at hand. He took off his hat respectfully, but there was no introduction in the case, beyond the quiet observation, “George, this gentleman has come to see you; sit down!”