Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"WHAT IS THE MATTER, LITTLE GIRL?"

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE

AUTHOR OF "PROBABLE SONS," "TEDDY'S BUTTON," "ODD,"

"JILL'S RED BAG," ETC, ETC.

WITH THREE ILLUSTRATIONS BY SYDNEY COWELL

SECOND IMPRESSION

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET; & 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

1905

STORIES

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE.

Odd Made Even. 3s. 6d.

Heather's Mistress. 3s. 6d.

On the Edge of a Moor. 3s. 6d.

The Carved Cupboard. 2s. 6d.

Jill's Red Bag. 2s.

A Little Maid. 2s.

A Puzzling Pair. 2s.

Dwell Deep; or, Hilda Thorn's Life Story. 2s.

Legend Led. 2s.

Odd. 2s.

Bulbs and Blossoms. 1s. 6d.

His Little Daughter. 1s. 6d.

A Thoughtless Seven. 1s.

Probable Sons. 1s.

Teddy's Button. 1s.

Bunny's Friends. 1s.

Eric's Good News. 1s.

London:

The Religious Tract Society

4, Bouverie Street.

Contents

CHAPTER

I. "THE FIRST STEP TO SERVICE"

VIII. "A REAL LITTLE HOME MISSIONARY"

IX. "I'M A-GOIN' BACK TO LONDON"

List of Illustrations

"WHAT IS THE MATTER, LITTLE GIRL? CAN'T YOU GET A PLACE?" Frontispiece

"THEN I COME HOME WITH A BROKEN 'EART"

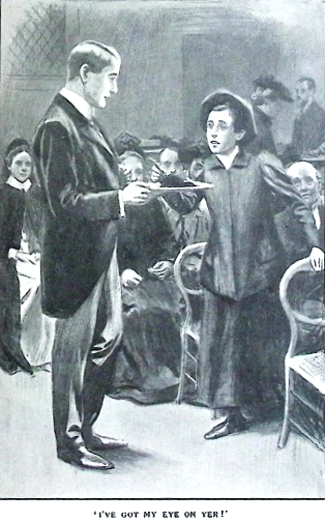

"DON'T YOU LAY YOUR FINGER ON IT, FOR I'VE GOT MY EYE ON YER!"

A Little Maid

"THE FIRST STEP TO SERVICE"

SHE sat on a doorstep in Bone Alley. Her surroundings were such as you may see any day in that part of London, which is known to the upper class as the Slums. And she herself was not a striking feature in her landscape. Nine out of ten people would have passed her by, without a look or thought.

She was dressed in a brown skirt, a black bodice, and a faded blue felt hat, with a wisp of black ribbon and a ragged crow's feather stuck jauntily in on one side. Her arms were hugging her knees, and two very dilapidated old boots rested themselves contentedly on a medley of orange-peel, broken bottles, and old tins. Her eyes were big and blue, her hair a nondescript brown, hanging in straight wisps round her small pinched face. But she was a dreamer.

A close observer would have seen that her soul was far away from her surroundings. A rapt smile crossed her face, and a light came into her eyes that nothing in Bone Alley would draw there. Then she gave her thin shoulders a little shake, and frowned.

"Peggy, you're gettin' up too high; come down!"

She was accustomed to talk to herself. There was no one near her. Further down, a barrel-organ was surrounded by a circle of dancing children.

"You'd best be movin', Peg," she continued. "Aunt will be callin' yer."

Slowly she got up, and then, with a little stretch of her long thin limbs, she shuffled up a steep staircase through an open doorway. Up, up, up! Three long flights of stairs. Different smells issued from the many doors she passed, and one could pretty well guess from them the employments of the occupants within—soapsuds, cabbage, fried bacon, and fried fish. Nearly every one at this time seemed to be cooking, for it was one o'clock, and dinners were about to be served.

At the very top floor Peggy paused. Not for breath, for her lungs and heart were sound; but her words explained it.

"Now, Peg, don't you say nothink at all when she rows yer—nothink, or you won't get out agen!"

She opened the door abruptly. It was a poor-looking room, but clean and tidy. A bed near the window contained a cripple woman, who was knitting away busily. She looked round at the child with a heavy frown, and her voice had a peevish nagging note in it.

"How much longer am I to wait for yer, I'd like ter know? Look at the fire, you lazy baggage! You be no more use to me since yer left school than you were before. What 'ave you been a-doin'? Me, slavin' and knittin' myself silly to give you food and clothes, and you out in the streets from morn to night! Dancin' round that organ, I'll be bound! Oh, if I were given the use of my legs agen, wouldn't I make you dance to a different toon!"

Peggy said nothing, but with a clatter and bustle she made up the fire, and then prepared the midday meal. Potatoes and half a herring, with a cup of tea, formed their dinner. Mrs. Perkins kept up a running stream of complaints and abuse, which Peggy hardly seemed to hear. She washed up, tidied the hearth, fetched her aunt some more wool from a drawer, and then slipped away towards the door.

"Where are you goin'?" demanded Mrs. Perkins. "I'll be wantin' you to take a parcel for me to the shop, an' Mrs. Jones have bin in to arsk yer to mind her baby. She have to go to 'orspital for her eye-dressin'!"

"I'll mind her baby now," said Peggy cheerfully, "and then I'll be ready for yer parcel!"

She ran down the stairs unheeding the remainder of her aunt's talk. On the next floor she met a stout woman, just opening her mouth for a call.

"I'm a-comin', Mrs. Jones. Was you wantin' me? Where's h'Arthur? Shall I take him out?"

Arthur was a big heavy boy of two years, but Peggy lifted him in her arms and staggered down the stairs bravely. Once in the street, she put him down on his feet.

"We'll come and see Mrs. Creek," she said. "I'm a-longin' to have a talk with 'er!"

Arthur gurgled assent, and stumbled along contentedly by her side.

She marched down the alley, then turned a corner into a more respectable street, presently paused before a tiny sweet-shop.

It was a clean little place; and behind the small-counter sat a cheery-faced little woman with spectacles on her nose and a work-basket by her side. How Mrs. Creek could live and thrive in such a neighbourhood was a mystery to many. The children loved her almost as well as her sweets. She had no belongings, but eked out her scanty living by mending and making for some of her bettermost neighbours. A card in her window asserted—

"PLAIN SEWING TAKEN IN."

But Mrs. Creek's needle was required for many varieties, from piecing a small corduroy breeches to trimming a bonnet; and darning stockings was her relaxation. She and Peggy were the greatest friends. She knew, though the cripple aunt was a respectable hard-working woman, she was a harsh task-mistress. Peggy waited on her aunt hand and foot, and never got a bright, pleasant word from her.

"Please 'm," began Peggy, dragging her small charge into the shop, "I'll have a halfpenny barley-stick for h'Arthur. And, please 'm, will you tell me once agen how you first went to service."

"Bless your little heart! Sit ye down, child, on that there empty box. And there's the barley-stick. Why, what a fine boy he is growing!"

Then she shook her head reprovingly at Peggy.

"You've no right to be longin' after forbidden things, dearie. Your aunt can't spare you, an' she have told you so."

"Yes," said Peggy, with eager eyes, and a little flush on her sallow cheeks; "but I dreams and dreams of it. An' it may come one day. Teacher told me on Sunday we can arsk God anythink, and—and I'm a—arskin' of Him to manage it for me. Tell me agen of your clo's, Mrs. Creek. They do sound lovely."

Mrs. Creek gave a little low laugh.

"I minds that I thought 'em so. 'Twas nursery maid at the Rectory I went to, and I couldn't sleep at night for thinkin' on it. I had two lilac print gowns, with sprigs of daisies over 'em, and four white aprons, and two pair of home-knitted stockings, and one pair o' new boots, and a pair of low-heeled slippers, and three white caps, and a black straw hat with ribbon, and a white straw bonnet for Sundays, and a grey linsey gown, and a neat black coat—"

She paused for breath, and Peggy gave a rapt sigh.

"Oh," she said, clasping her hands, "how rich yer mother must 'ave been! How lovely to feel they was all yours! Go on, 'm, please. Tell 'ow you felt when you treaded on carpets!"

"They was lovely and soft," the old woman said meditatively; "an' the nursery with its big fire and bright brass fender, an' the pictures and toys, an' the red-cushioned rockin'-cheer, I seem as I can see it all now. The nurse were tall and stern, but the little ladies, there were three on 'em, they were always ready for a game with me. And I used to swing 'em on the lawn, and help 'em to clean out their rabbit hutches. Dear life! What a happy little maid I was!"

Peggy gulped down a sob.

Mrs. Creek looked at her and saw that tears were running down her cheeks.

"It seems like 'eaven," she murmured, wiping her tears away with the back of her hand and hoisting Arthur on her lap, as the little urchin was getting restless. "How little could you go out to service with, 'm, please? If you was ever so careful, wouldn't one print dress be enough? You could wash it out careful when you went to bed—leastways, any dirty patches you could."

Mrs. Creek shook her head.

"If you goes to ladies' service you must 'ave an outfit," she remarked importantly.

"Like as if you were goin' to marry!" said Peggy, with another big sigh.

"But," said Mrs. Creek, "'tisn't many got such a chance as I had. I was country-born, ye see, an' my father were under-gardener at the Hall."

Peggy's face became gloomy.

"Tis no use hopin', is it? I 'ave saved up some pence, 'm. Just what I've earned proper, but see—'ow many before I could get a gown? Why, hundreds, wouldn't it be?"

She produced out of the bosom of her shabby bodice a dirty-looking piece of rag; unknotting it carefully, she counted out sevenpence halfpenny.

Mrs. Creek nodded and smiled.

"That's a beginnin', dearie. Maybe by the time yer aunt will be wantin' yer no longer, you'll have a goodish sum."

Peggy brightened up.

"And 'ow did you stick your caps on, please 'm? Did you have longer hair than mine?"

"Well, yes, I think I had a fine lot in those days, and I plaited it neatly and had a nice flat cap, not one o' these cockatoo sort o' arrangements that girls wear nowadays."

"And tell me now about the rooms, please 'm!"

Mrs. Creek began her descriptions, that had already been given to Peggy many and many a time before; but the child listened with open mouth and eyes, until small customers began to crowd in. It was Saturday, and fathers had come home from their work with pence to spare. Mrs. Creek had to put aside her reminiscences for the time, and, after waiting a little longer, Peggy reluctantly departed with her charge.

A sharp-faced girl soon joined her outside.

"'Ulloo, Peg! H'aint seen you for years."

"Where have you bin?" demanded Peggy.

"I've j'ined the boot factory, and, I say! H'our Emma has gone to be a slavey!"

"Has she? Where? I wish I could!"

"You be a pair o' sillies, the two on yer! Catch me bein' a slavey! No, not I!"

"Where has Emma gone?"

"To the pork-butcher's. An' her missis hit 'er with a bootbrush las' Saturday. I'd like to have had that done to me!"

"When I goes to service," Peggy said loftily; "I shall go out to real ladies, who don't keep no shops."

"I'd start with Buckingham Palace," said the factory girl witheringly; "but p'raps that wouldn't be 'igh enough for yer!"

Peggy promptly parted company with her. She turned into a broad street with her little charge, and sauntered past lines of shops, occasionally pointing out some desirable objects to him, but for the most part pursuing her thoughts in silence. At last a smart draper's brought her to a standstill. Peggy often amused herself by pretending she had come out with a full purse to buy an outfit for service. Now she could not resist playing at the same old game.

"Now, Peggy, take your choice. There are prints there, pink and blue, but no dark lilac like Mrs. Creek had. But that's a pretty stripe over in the corner. You'd look fine in that. And oh my! What cheap caps, with real broidery round 'em, and only twopence three farthings each!"

She paused, and looked at the caps longingly.

"If I could try 'em on, just to see how I looked, and if I could pin it on proper! Why shouldn't I buy one? There now! Come on, h'Arthur, and I'll do it, this very minit!"

Into the shop she went with the air of a duchess. If there was anything that Peggy loved, it was shopping. "Tis the only time folks is civil," she would say. "They don't bawl at me, nor yet scold then, and it makes me feel as if I'm a bigger person than them!"

"I wish to see some of them there caps, please," she said, taking a seat at the counter, with her chin well tilted up. "Caps for service I want."

"Certainly," said a young woman politely, "here are a cheap lot just come in."

"I hope they washes," Peggy said, up one on the tip of her finger. "Sweepin' rooms do make one's caps so dirty," she added, with a knowing shake of her head.

"Oh, they wash right enough," was the reply; "see here, catch hold of this string, undo it, and they come out flat! There you are!"

Peggy gazed at the cap, trying hard to conceal her surprise.

"'Tis like a Jack-in-the-box!" she said to herself; then aloud—

"I'll take one, please, and try how I like it. I'm rather partic'lar as to caps."

The young woman tried to conceal a smile, but she wrapped the purchase up into a small parcel, and Peggy departed in great spirits.

"'Tis the first step to service," she said; "but I don't know where I can try it on. Aunt has the only looking-glass. And I don't like tellin' to Mrs. Creek; she'd think it silly!"

She went home with Arthur, then climbed the steep stairs again. She crammed the cap into the pocket of her dress, then went in and was met with her aunt's usual greeting—

"Wherever have you been, you good-for-nothin' girl? And my parcel ready and waitin' this last hour, and the fire nearly out, and the kettle not near boiling!"

"I've been out with h'Arthur. I'll make up the fire in a second!"

She was not much longer, and then, a few minutes later, sallied out to take her aunt's knitting to one of the City shops. Mrs. Perkins warned her not to be out long, and Peggy sped along the busy streets, racking her brains as to how and where she could try on her untidy little head the stiff snow-white cap that she had bought.

The parcel was delivered, and she received two shillings in payment, which she carefully tied in a corner of a red handkerchief round her throat. Then she retraced her steps homewards.

On the way her eyes lighted on a heavily laden dust-cart in front of her. Something glittered among some rotten cabbages. Peggy's eyes were sharp. She saw that it was a piece of broken looking-glass.

"The very thing for you, Peggy," said she. "Now if you gets that, you'll be in luck indeed!"

She approached the dustman with all the assurance of a London child.

"Hi, mister, jest shy me that piece of glass! I wants it badly."

The man looked at her and it. Then he laughed. "It'll show you no beauty," he said, with a chuckle.

"No," said Peggy seriously, "but it'll keep my hats and bonnets straight on my 'ead."

He came to a standstill. Then with his shovel, he drew out the piece of glass and presented it to her.

Peggy was profuse in her thanks. She hid it under her jacket, and got home in such haste that even her aunt had little fault to find with her.

It was Sunday. She was up early, for she had a lot to do before she was at liberty to go out, and Peggy attended a Sunday School close by, and always went to church on Sunday morning. After that, she stayed in with her aunt for the rest of the day.

Sunday afternoon was the time for Mrs. Perkins' visitors to come and see her. Sometimes it was a neighbour who dropped in for a chat; sometimes a married niece; but there was always a cup of tea going if nothing more, and Peggy waited on everybody and listened to the talk with interest, though she was never supposed to speak.

She went off to Sunday School this morning in a happy frame of mind. Possibilities of a good place always seemed to centre in Miss Gregory, her teacher; and Peggy had made up many wonderful stories about this young lady. How one Sunday morning she would come to school and say,—

"Peggy, I have for a long time thought you would make me a good little servant. Now I am sure of it. I will come round and talk to your aunt, and I will buy you some clothes and next week you shall come to me."

Sometimes Peggy's fancies took a still higher flight. Miss Gregory would say,—

"Peggy, I am buying a house in the country. It is a Rectory, and I have bought the church with it. It has a beautiful garden, and flowers and fruit; you must come with me and be my servant."

I am afraid Peggy's thoughts were often far away from her lessons. She secretly adored her teacher; but if I were to tell the real truth, Miss Gregory looked upon her as a quiet dull little scholar, who was less attentive than many others, and who seemed the most uninterested of them all.

But to-day the lesson attracted Peggy from the very first. It was about the little captive maid who told Naaman's wife of the great prophet who could cure her master. She listened with big eyes and open mouth to the story.

Miss Gregory wound up with—

"And so you see, children, what a lot of good a little servant-maid can do. She had been taken away from her home and friends, and might have been fretful and sulky, and unwilling to help her master. Instead of that, she longed to tell him how he could be cured."

"Should think so," gasped Peggy; "she must have been awful glad to leave 'ome, and go to service!"

There was something in her intense tone that made Miss Gregory look at her. But she felt she needed rebuke.

"No little girl ought to like leaving her parents and going away from them. Good little girls would not like it."

Peggy hung her head abashed. Her next neighbour nudged her sharply with her elbow.

"One for you, Peg!" she whispered.

Peggy gave her a vicious kick, which brought upon her a severer rebuke still from Miss Gregory, and when the class was over and the children dispersing, Peggy was kept behind.

"Don't you ever wish to love Jesus, Peggy, and please Him?" her teacher asked rather sadly.

Peggy looked upon the ground and said nothing.

Miss Gregory went on, "I have often wished you took a greater interest in the Bible, Peggy. You always seem to be thinking of other things. Don't you like hearing Bible stories?"

"About servant-maids I does," said Peggy, looking up with a bright light in her eyes.

"You like that, do you? Why? You are not in service yet, are you?"

"No, teacher. I live with aunt, and does for her."

"Then you ought to be a happy little girl to have a comfortable home, and not have to go out and earn your own living. Maids-of-all work have a miserable time; you need not wish to be one of them."

"But I wants to get into a good place with real nice ladies!" said Peggy earnestly.

Miss Gregory shook her head.

"You would have a lot to learn before you could do that."

"But the girl in the Bible went right into a lovely place. You said her mistress was great and rich. I'd like to wait on a lady like that!"

Miss Gregory smiled, as she noted Peggy's downtrodden aspect.

"Well," she said, "perhaps one day you'll go into service, and if it is a shop, you can serve God as well there as in a palace. Don't wait for great things, but be faithful in small. Now follow the others into church. I am coming."

Peggy's hopes were again dashed to the ground.

"'Tis no good, Peggy," she murmured to herself. "Teacher won't never help yer. She thinks you too bad."

She went to church, and when she bent her head in prayer before the service began, this was her petition—

"Oh God! You'll understand, if she don't. And please find me a place

as good as that there leper capting's, and send me clothes, and let aunt

let me go. For Jesus Christ's sake, Amen."

Then she lifted her head with bright hope shining in her eyes.

"God 'll do it better than teacher. He's sure to have heard me to-day, 'cause it's in church."

She went home comforted, and through the whole of that day, her busy brain was thinking over the story of the little captive maid.

"I'd like to do somethin' grand like that. In the first place I gets, I'll try. I'll go to a place where there's a ill gent, and I'll tell him—I'll tell him of them there pills that cured aunt's cousin, and if he'll try 'em and get well, 'twould be grand for me. O' course, 'twouldn't be like tellin' him of a prophet, but teacher says there's no prophets now. But it's easy to do grand things in service. If I never gets a place, it's no good thinkin' of 'em."

And so with alternate hopes and fears, Sunday wore away. Not once did she got chance of looking at her precious cap, but the knowledge of her possession was joy to her.

"IN SERVICE TO MY AUNT"

EARLY the next morning she woke, and hearing by her aunt's heavy breathing that she was sound asleep, she cautiously sat up in her little iron bed.

She would like to have drawn aside the old curtain from the window, but she dared not cross the floor.

Her aunt was a light sleeper, and her only chance of an uninterrupted time was whilst Mrs. Perkins was unconscious of her presence.

So, as quickly as she could, she propped up her bit of glass against the wall, and proceeded to array herself in her cap. It was rather a difficult process. First her hair had to be rolled up in a little knob, and it was too short to be tractable. Ends kept sticking out, and then nothing would induce the cap to keep in its rightful position. She pinned it here, and she pinned it there, and each time got it more crooked. But patience and perseverance at last won the day, and Peggy surveyed herself with rapture.

"Yes," she said aloud, with a pleased nod at her reflection. "You look a first-rate servant, Peg. Quite a proper one, and you could open the door to a dook quite nice. 'Come in, sir, please. Glad to see you, sir. Will tell my missus you're here, sir. Yes.' Oh lor!"

Her head was tossed so high, that off flew her cap, and a querulous voice broke in upon her make-believe.

"Now what on earth are you doin' of, Peg? Are you going crazy? What are you a-dressin up for, at this time o' mornin'?"

Peggy's cheeks turned crimson. She scrambled into bed.

"Are you crazed?" repeated her aunt. "Tell me what you're a-doin' of. Lookin' like a monkey with a white thing on yer 'ead! Speak at once, you good-for-nothin'!"

But Peggy felt overwhelmed with shame and confusion. "I 'spect I was dreamin', Aunt. Leastways you'd think so—I was—I was playin' at bein' a servant."

She made her confession in a contrite tone.

"Little fool!" said her aunt, but she turned over in her bed and went to sleep again, and Peggy did not stir till a clock outside struck seven, and then with a sigh she got out of bed, and carefully secreted her bit of glass and her cap under her mattress. It was her only hiding-place, and had held many a queer assortment of articles from time to time.

When she was dressed, she went out to get a 'ha'poth' of milk for breakfast, and this was the time that she took to pass through a quiet, respectable street, not very far away, where servant-girls were to be seen cleaning the doorsteps. This street—Nelson Street by name—had a fascination for her; she took great note of the different caps and aprons worn, and occasionally was fortunate enough to exchange words with some of these envied young people.

To-day she addressed a new-comer on the doorstep of No. 6. Peggy had seen a good many fresh girls on these particular doorsteps; some of them had stayed a few weeks, others for a few days. She always knew the fresh arrivals by the cleanliness of their gowns and the tidiness of their hair; but this new-comer seemed a shade fresher and cleaner than any she had yet seen. She had red hair and rosy cheeks, and her gown was nearer Mrs. Creek's pattern lilac one than any Peggy had noted.

"You're new," asserted Peggy, as she came to a standstill.

The girl turned and looked at her.

"Who are you?"

She did not say it rudely, but with curiosity. Peggy had had many a snub from those servant-girls; few of them would deign to notice her, so she was quite prepared to be ignored.

"Oh," she said, looking at her questioner going admiringly, "I'm going into a place one day, and I comes and looks along this street, and wonders which house I'd like to be in. Who lives in yours? Any one beside the lady that scolds?"

"That be my missus right enough, for I only come in day 'for yesterday, and never have done nothin' right since. There be two gentlemen lodgers, and one first-floor lady that teaches music."

"Oh," sighed Peggy, depositing her small milk jug on the step, and placing her arms akimbo. "If only I could get into service, I'd be real happy."

"I live down in Kent," explained the red-haired girl. "But the country is too quiet, I want London; and so I've come up to my uncle's step-sister."

"But the best places must be in the country," said Peggy. "I'd a deal rather live out o' London. 'Tis so much cleaner for yer caps and aprons—Mrs. Creak says so."

"You are a queer one," said the red-haired girl, staring at her.

Then a voice from an open window called to her—

"Liza, Liza! Come this minute!"

She darted indoors with pail and broom.

Peggy walked on.

"No," she said; "I won't take Liza's place, not if I know it!"

She went into Mrs. Creak's little shop soon again.

"You see, 'm," she said, "I believe if some one was to come and talk my aunt over, she might let me go. There's a girl on the ground floor who would do for her for sixpence a week. Now, if I was out, wouldn't I be gettin' that?"

"Well, yes, dearie, and a good bit more."

"Then I'd be able to pay the girl, and aunt would be looked after. Oh, please 'm, couldn't yer come round one day and talk to aunt."

Mrs. Creak shook her head doubtfully.

"I couldn't myself, but there's the district lady. I could speak to her."

"She's no good," said Peggy. "Aunt won't let her indoors. She says she talks too much religion. She giv' her a trac' one day called 'The Happy Cripple,' and aunt said she were pokin' fun at her."

"Ah," said Mrs. Creak, with a little sigh, "your aunt ain't found out that happiness is found in the very folk who seem to have the least to make 'em happy. I should say your aunt would be better for more religion, my dear."

Peggy leant forward and spoke under her breath—

"She don't like God, 'm, and that's the real fac'! When her legs were hurt under the waggon, and she never walked agen, she giv' up sayin' prayers."

"Poor thing! I never knowed your aunt, Peggy. She were a cripple when I come here, and a person that kept her door shut to most folks. It's like a person shuttin' out the light o' day, to shut out the Almighty."

Peggy nodded.

"And so I wants to leave her and go to service. Please 'm, did you ever hear in the Bible of a leper capting and a little servant-maid?"

"Why, certain I have. 'Tis Naaman you'll be meaning."

"That be his name. I'm wantin' to get a place like that. I dessay she weren't older than me, and see what a lot o' good she did! I mean do an orful lot o' good when I goes into my place!"

Mrs. Creak gazed at the child's big earnest eyes for a moment without speaking. Then she put down the stocking she was darning, and tapped her thimble on the counter.

"Now listen to me, Peggy Perkins. You're in a place now, and in the place that God Almighty chose for you. You're a little maid to a poor, unhappy cripple, who can't move from her bed. Now what good do you ever try to do to her?"

Peggy looked quite startled.

"Why, 'm, aunt is just aunt; I ain't in service."

"Yes you be, dearie. You be servin' her day in and day out. Do you ever try to make her feel a bit happier? Do you tell her of bits you hear in Sunday School, to make her know that God still loves her?"

Peggy drew a long breath.

"Why, I never says nothin' to her more than I can help."

Customers as usual interrupted the conversation, but Peggy departed from the sweet-shop with new ideas in her head.

"'Tis as teacher said to you, Peggy—you're a lookin' for big things and not mindin' the little. But, oh lor! To think of me bein' in service to my aunt! If she were a missis, I wonder if I'd like her better!"

She pondered slowly as she walked down the street.

"Wonder what that there maidservant in the Bible would have done if she'd been lookin' after aunt! But there's no cure for cripples that I knows of, or I might be able to do her good."

She passed a flower-girl selling violets, then she looked back at her, and a bright idea struck her.

Hastily she felt for one of her precious coppers, and after considerable haggling over the bunches, she selected one, paid her penny, and ran off home as fast as her legs could carry her.

When she came in she found her aunt lying down, her work, untouched, by her side. This was such an unusual sight that Peggy was quite taken aback.

She stepped across the room quietly.

"I've brought you some vi'lets, Aunt, to smell."

Mrs. Perkins turned in her bed. Her face looked white and drawn.

"I've that queer pain in my side agen, Peg," she murmured. "Give me a drop o' gin and hot water."

Peggy put down her violets hastily, and went to the cupboard for the gin bottle, which, for Mrs. Perkins' credit, I must say, was hardly ever used by her.

She soon brought her some hot drink in a tumbler.

Mrs. Perkins seemed better after she had drunk it, and once more sat up in bed.

"It took me all of a sudden," she explained; "and I've a lot of work to be got through. Here, Peggy, give me over that wool. Did you say you 'ad some vi'lets? Where did you get 'em?"

"I bought 'em, Aunt."

"Bought vi'lets!" Mrs. Perkins' tone changed. "Why, you wicked, wasteful girl! And where did you get the money? Me lyin' here and slavin' from morn to night to keep us from starvin', and you out in the streets a-buying flowers like any carriage lady! You ought to be ashamed of yerself, that you did!"

Peggy hung her head.

"I bought 'em for you," she murmured. "I thought as 'ow you'd like to smell 'em!"

Mrs. Perkins gave a scornful smile.

"A very likely story. Don't you tell me no more lies! Bought 'em for me, indeed! When did you ever do such a wonder? The skies might fall before you'd give a thought to your sick aunt! You takes her money and vittles, and the clothes she gives yer, and you grumbles at all you has to do for her. Oh! If ever you loses your legs and lies on a hard bed, may you know what it is to have an ungrateful girl a-waitin' on yer!"

A sullen look crossed Peggy's face. She did not attempt to argue the matter out, or prove herself in the right. But she felt as if she would never try to do a kindness to her aunt again. She began to make preparations for tea, and she pitched the violets down on the floor.

That gave an occasion for another scolding, and Mrs. Perkins finally gave orders that the flowers were to be put in a tumbler of fresh water and placed on the window-ledge.

"I only 'opes as you came by 'em honest; but there's no sayin'. I may as well 'ave the good of 'em now they're here."

Peggy was wakened out of her sleep that night by a call from her aunt.

"That old pain agen! It must be those shrimps I took. Oh dear! Oh dear! I feel as if I can't bear it!"

"Shall I rub you?" asked Peggy.

When her aunt seemed weak and helpless, she felt pity for her at once.

Mrs. Perkins let her try to rub her. Some more gin and water was administered, and then she seemed easier. Peggy sat at the bottom of the bed and watched her.

"Ah!" Mrs. Perkins said, with a groan. "I dessay my days are numbered. These pains are cruel; they must mean somethin'. But if I die, there 'll be no one to miss me."

"I shall, Aunt," said Peggy honestly. "I've been thinkin' I'll be a better girl to you. And I'll tell you what I hears in Sunday School, and anythin' to make you a bit happier!"

Mrs. Perkins groaned, and shook her head.

"There's nothin' will make me happy," she said; "but there be plenty of room for improvement in you, Peg."

"Yea," said Peggy, humbly and determinedly. "I've made my mind up to do yer good, same as the servant-maid did to the leper capting. An' I'll tell yer all I hears, and you can pick out the bits that soot yer, and ease your mind like."

"I don't want ter hear religion," said Mrs. Perkins, with an indignant sniff. "If there be a God, He have treated me shameful! I won't have nothin' to do with Him!"

"God loves yer, Mrs. Creak says," said Peggy undaunted. She was still sitting at the bottom of the bed, staring at her aunt; and now her eyes took a dreamy turn. "Anyways, you ain't been mocked and whipped and crucified, same as Jesus Christ, and God loved Him ever so, teacher said so. I s'pose as how God loved us ever so, and let us come first, when the Crucifixion come along!"

"Get into bed with yer, and don't talk my 'ead off!" was the irritable comment of Mrs. Perkins.

Peggy promptly obeyed.

When she woke the next morning, her aunt was much as usual. The midnight talk seemed a dream; neither of them alluded to it, and life went on as before till the following Sunday.

Peggy went to school that morning with a fixed resolve in her busy brain.

She lingered behind the other children when school was over.

"Please, teacher, I wants to arsk you somethink."

"Then you shall walk to church with me, Peggy. We are quite early, so sit down again. What is it?"

"Please, teacher, is there no ways of gettin' a cripple cured now, same as the leper capting in the Bible?"

"You mean Naaman? Well, no, Peggy. God does not work miracles now, nor let His servants do it; there is no need."

Peggy's face fell.

"Then poor cripples can't be done good to by no one?"

"Oh yes, indeed," and Miss Gregory's face brightened. "Their hearts may be made well and sound and happy, Peggy; and after all, that is the best part of us, isn't it? We think a lot of our body, with its aches and pains, but it is only a cage. I passed down a narrow dark street yesterday, and outside a window there was a thrush, singing as sweetly as if he were perched on a tree with a beautiful green world all around him. Do you know where thrushes generally live, Peggy? In the sweet country, with flowers and dew-laden grass, and the free, clear air to fly in, with nothing above them but the infinite blue, and other birds to live and play with all day long. That is the world to sing in, and this little fellow was in a smoke-grimed cage about a foot square; he could only see soot and dust and fog, and screaming, quarrelsome men and women, and children who sometimes tried to hit him with stones. Yet he sang his song as merrily and sweetly as any free, country bird. He had a happy heart. And if we have a crippled body, we can have a singing heart."

"How?" said Peggy, with big eyes and still bigger thoughts.

"By asking Jesus to come into our hearts and make them sing. Have you ever asked Jesus to come into yours, Peggy?"

"I prays to Him," said Peggy reflectively; "but I don't expec' He'd care to live in my heart. It ain't fit for Him. Aunt says I be a wicked girl."

"However wicked your heart is, it can be washed whiter than snow, Peggy. Jesus will do that if you give your heart to Him. He will make your heart fit to receive Him, and if He 'abides in us,' we are told we shall bring forth much fruit; you will be helped to be good and guarded from evil if Jesus is taking charge of you."

"I'd like Him to," said Peggy, with a determined little nod.

"Then shall we kneel down here together and ask Him? You speak to Him, Peggy, and remember that He is waiting to hear and answer you."

So Peggy bent her head and shut her eyes.

"I arsk you, Lord Jesus, to take hold of my heart and wash it, and make it proper; and please come into it and give me a singin' heart, and I gives it up to you like teacher says I ought. And please help me to be good, for I'm awful wicked."

There was a little silence in the empty schoolroom. Then Miss Gregory prayed aloud for her little scholar, that she might be kept a true and faithful little follower of her Saviour. And when they rose from their feet, Peggy's face was very sweet and serious.

"I'm never goin' to be wicked no more," she asserted.

Miss Gregory smiled, then told her to follow her to church; and on the way talked very earnestly to her, trying to make her realise how weak she was in herself, and how strong her Saviour.

When Peggy reached home, and sat down to the luxury of a mutton chop with her aunt, she began to think how she could pass on what she had heard. It was very difficult. Mrs. Perkins was more discontented on Sunday than any other day in the week. She had time for airing her grievances, and her tongue certainly never had a Sabbath's rest, if her hands had.

"Aunt," said Peggy at length, bringing out her words with a jerk, "do you ever feel like singing?"

"Are you givin' me some of yer imperence?" was the angry retort.

"Oh no, I ain't a-goin' to sauce yer! Teacher, was a-tellin' me of a sick body havin' a singin' heart."

"I dessay," Mrs. Perkins said scornfully. "Let yer teacher wait till she has a sick body, and then let her sing!"

"I 'spect she would," said Peggy thoughtfully. "She says how you does it is to ask Jesus to come into your heart, and He'll make it sing."

Mrs. Perkins gave a contemptuous snort.

Peggy gained courage, and proceeded—

"I was arskin' her if sick folk that couldn't be cured by doctors could be done any good to, and she says, 'Yes, their hearts could be made well and sound and 'appy. It sounds cheerful like, don't it? I thought as 'ow you'd like to hear it."

"Much obliged," said Mrs. Perkins sarcastically.

There was silence. The meal was finished. Peggy washed up and tidied the room. Her aunt lay back in her bed, and appeared to be studying a Sunday paper. But suddenly Peggy heard her give a little cry.

"That there pain agen! Oh for! Whatever shall I do? 'Tis a-takin' hold o' my inside, like a lobster's claws!"

"I'll get the gin," said Peggy.

But her aunt would have none of it. She moaned and cried, and then began to talk incoherently.

"'Tis nay 'eart, I know 'tis, and I shall be dead before long. A 'appy heart! Ay, 'tis fine talkin'! Singin'! I mind in Sunday School I could sing the 'eartiest o' them. How does it go?

"'Oh for a 'eart to praise my God,

A 'eart from sin set free.

A 'eart that's sprinkled with the blood

So freely shed for me.'

"What do you say, Peg, about the love o' God? Oh lor! Oh, fetch the doctor, quick, quick!"

A spasm of agony seemed to pass over her.

Peggy rushed from the room.

"Mrs. Jones!" she shouted at that good woman's door. "Go to aunt. She be mortal bad! I'm off for the doctor."

It was not long before she was back again with the young practitioner who lived not far away. But Mrs. Perkins was already beyond all human aid, and Peggy for the first time in her life realised what an awfully sudden and unexpected messenger Death may sometimes be.

"I'M READY FOR MY PLACE"

THE next few days were dark and bewildering ones to Peggy. Mrs. Jones proved a friend in need. She took her to her room at once and mothered her as she had never been mothered before. Peggy was grateful, but she was not comforted till she paid a visit to Mrs. Creak.

"'Tis so awful me havin' wished 'er dead many a time, Mrs. Creak! I thinks of it at nights. And I was so cross and sulky and imperent, and now she be gone. And oh! Mrs. Creak, where is she?"

Mrs. Creak was silent. Then she said softly—

"You gave her a message, dearie. Her last thoughts were about God and His love. She may have put up a prayer for mercy. She were very near it from the hymn you tells me she quoted—

"'Oh for . . . a heart that's sprinkled with the blood

So freely shed for me.'

"It may have set her thinkin' and then prayin', dearie. 'Tis very remarkable she should have minded it just then. But oh! Peggy, my girl, never you leave it to make your peace with God till He calls you! He do call so terrible sudden sometimes."

Peggy nodded soberly.

"I ain't goin' to say another cross word to no one all the days o' my life 'm, for fear they should die sudden 'fore I could make it up with 'em."

"That's a very grand resolve," said Mrs. Creak, "but it's too big a one to keep, Peggy, if ye don't ask the Lord's help."

"The Lord helpin' me—Amen," finished Peggy fervently. Then, after a big sigh or two, she came to business.

"Please 'm, Mrs. Jones wants me to stay and mind h'Arthur, and she'll give me my vittles and clothes, but I wants to go to service."

"I know you do, dearie, but 'tis difficult for you at present."

"Oh, please 'm, do you think God is answerin' my prayer? I've been arskin' Him fearful hard to let me go to service, but I do hope I haven't been and made aunt die."

She stopped, aghast at the thought. But good little Mrs. Creak reassured her.

"God has our lives in His hand, and no others have, Peggy. He took your aunt away, but I doubt if it will be easy even now for you to get into real good service."

"Why?"

"There be your clothes, child. You have none fit to wear, and it takes a good sum to get things together. And then you have no trainin' at all. If you could go to a trainin' 'ome now."

"That I never will!" said Peggy stoutly. "I won't go to the 'Ouse or any such institootion. I'll manage 'm. I know a good many girls in places, an' they 'll 'elp me."

Peggy did not let the grass grow under her feet. She followed her aunt's funeral in company with three other women who took pity on her. And then, when she had come back and packed up her belongings, she gave the key of her room to the landlord and went to live with Mrs. Jones.

The very next day she was haunting Nelson Street, and eagerly talking to the red-haired girl at No. 6.

"I'm a-goin' into a place as soon as I can find one," she assured her importantly; "but I don't want to live in this street."

"That's a pity," said the red-haired girl good-naturedly, "for No. 14 is a-goin' to be married, and she's leavin', and you might a-tried there."

Peggy's face lit up with a splendid inspiration.

"Is that No. 14 a-cleanin' her doorstep?" she asked breathlessly.

She was assured it was. Off she marched, and opened fire at once.

"I say, I hear tell you be leavin'. How soon?"

The servant-girl looked round. She had a pretty little face, but her dress, cap, and apron were in a pitiably dirty condition.

"Yes, I'm leavin', thank goodness!" she ejaculated. "What business be it of yourn?"

Peggy's eyes were not on her face, but on her dress. She was taking stock mentally, and murmured to herself—

"Be careful, Peg! Two darns in the back, a slit in the elbow, and a washed-out blue!"

Then she spoke.

"How much for your cotton dresses? Will ye sell?"

"Sell 'em!" exclaimed the girl. "Be you clean demented?"

"But you won't be wearin' cotton when you're married," urged Peggy; "and I'm certain sure your gowns would fit me. I'll give yer two bob for this one, and that's a very good offer."

The girl looked at Peggy with some amusement.

"I don't care if I do sell you this one. I'm a-leavin' to-morrow."

"But it must be washed," said Peggy firmly.

"Oh, I ain't a-goin' to have it washed. You'll take it as it is."

"Then sixpence off!" said Peggy.

The bargain was struck. Late the next evening, Peggy arrived at the sweet-shop in an eager, excited state.

"Here I am, please 'm, and two print gowns for three-and-sixpence; one dirty and one clean. And the hems will turn up, and they only want a bit o' mendin'. You see 'm, there's ten shillings of poor aunt's that come to me, besides the five that Mrs. Jones got my best black with, and she giv' me a black hat; so now I've got six shillings and sixpence for boots, and a jacket, and aprons, and another cap; and please 'm, do you think I shall do then?"

Mrs. Creak looked at the enterprising Peggy with amusement and a little respect.

"I see you be quite determined to go to service, Peggy, so I'll do what I can to help you. Give me the dresses, and I'll see to 'em. If you gets clothes, you won't be long in finding a place."

A fortnight later, Peggy had the joy and satisfaction of seeing a very modest outfitin her one wooden box. Mrs. Jones had been good to her, and given her several cast-off garments of her own, which clever old Mrs. Creak had cut up and altered and turned out in quite good style.

"'Tis not only the outside of your back wants covering, my girl; and remember that good stout petticoats and well-mended stockings will keep you warm and well in the coldest weather."

"Yes 'm," said Peggy meekly.

And then she added anxiously, "And, please 'm, I'm tryin' hard to fasten my hair up. I've a-been lookin' at the girls in Nelson Street. They mostly has a curled fringe, but I can't make mine curl nohow. I've tried curl-papers, but I don't seem to manage 'em right, and them curlin'-tongs cost money."

"Now, Peggy, you take my word, and brush your hair smooth. Ladies will like it much better. Plait it neatly behind; them fringes be traps for dirt and dust, and take a lot o' time fussin' over."

"But," said Peggy, "I want to look proper 'm; I don't want to look like a Noah's Ark servant. Mrs. Jones says girls must make the most o' theirselves. And a fringe makes a cap look first class!"

"You try my way first. I know good service, and 'tis the best servant-maids wear the plainest heads."

So reluctantly Peggy gave up all idea of a fringe. She appeared in Nelson Street one morning and spoke to her red-haired friend.

"I'm ready for my place," she said, with much pride.

"No. 9 is wantin' a general," said Eliza.

"Who lives there?"

"A widder and six children."

"Oh my! I couldn't do for 'em. What does a general do, Liza?"

"Most everythink—washin' and cleanin', and cookin', and twenty other things besides."

Peggy gave a little shake of her head.

"I don't think I'll go to No. 9. I should like to live in a bigger street than this. I'm on the look-out for a house with a garding!"

"Why don't yer go to a Registry?" suggested Eliza. "That's where I should go, only uncle were so wild for me to come 'ere."

"What's a Registry?" asked Peggy. "'Tis where they marries folks, ain't it?"

"No, silly! Yer puts your name down, and what yer can do, and then when a lady comes along, they giv' yer name to her, and she sees yer, and if she likes yer she takes yer."

Peggy's eyes shone.

"That's first-rate. I'll go this afternoon, and I'll put on my best black. Where is there one?"

"The girl at No. 14 who's just come, tells me there's one in Friars Street, No. 54."

Peggy repeated this to herself, and walked home radiant. She did not tell Mrs. Croak of her intention, for she had a fear that she might stop her. In this conjecture she was right. Mrs. Creak was old-fashioned, and did not think much of Registries. She had told Peggy she had mentioned her to the Bible-woman and to the district visitor, and they had both promised to look-out for a place for her. But Peggy found waiting was a trial, and so she took her future into her own hands, and when she was arrayed in her black frock and hat, she informed Mrs. Jones that she was going out to look for a place.

"Good luck go with you!" said that good-natured woman. "And mind you say you can mind babies well, Peg. I'll speak for you there, for you've minded h'Arthur h'off and h'on since he cut his first tooth!"

Peggy marched away. She looked at her reflected figure in the shop windows with great satisfaction.

"You look grand, Peggy!" she ejaculated. "Fit to be in a real good place, and you see you get it, that's all!"

She found the Registry. It was a Berlin Wool shop, and a large card printed in the window stated that it was a "Servants' Registry."

She went boldly in, and addressed a stern looking-woman behind the counter.

"Please 'm, I've come to look for a place."

"What kind of place?" demanded the woman. "Have you ever been out before?"

"No," said Peggy importantly. "This is my first place, so I'm very partic'lar about it."

"And what can you do?"

Not a glimmer of a smile crossed the questioner's face.

Peggy drew a long breath. She had rehearsed it too often to be at a loss.

"Please 'm, I can scrub floors, and clean grates, and make beds, and clean winders, and sweep and dust, and mind babies, and cook 'taties and tripe, and mutton chops, and steak, and red herrings, and make tea and gruel, and hot drinks of gin and water, and nurse cripples, and run messages, and wash clothes, and—"

"That will do. Your name?"

"Margaret Perkins, please 'm."

"Your age?"

"Thirteen 'm."

Another grave-faced woman came forward.

"There's a lady waiting for a girl," she said, in a murmur. "She doesn't mind training them, she says. Shall I let her see her?"

Peggy's checks got crimson with excitement. When she was ushered into a little back room, and was confronted by a tall melancholy woman in black, she felt that this was a crisis in her life.

"Is this a respectable girl, Miss Shipley?"

Peggy did not give Miss Shipley time to speak.

"I'm quite respectable," she said. "I'm goin' to service because my aunt has died. Lots o' people know me."

The lady looked at her gloomily.

"You look very small," she said. "Are you strong?"

"I'm quite strong, please 'm, and, please 'm, have you an ill 'usband? That's the place I'm lookin' for. To wait on a lady with an ill 'usband. But I can mind your babies for yer. I'm first-rate with babies, so long as there's only one in arms."

Miss Shipley turned sharply away. The lady frowned ferociously upon Peggy.

"I am a single lady," she said, "and want a clean honest respectable girl, who does her work, and keeps a quiet tongue in her head."

Peggy was not a whit abashed.

"I don't talk if I'm not wanted to," she said; "only, please 'm, what kind of 'ouse do yer live in? Has it a garding? And is there carpets on the front stairs? I'm lookin' for a real nice place."

"Miss Shipley!" called the lady sharply. "This girl will be no use to me; she is either most impertinent or half-witted."

Peggy was bustled out, wholly unconscious that she was in fault. Miss Shipley enlightened her.

"If you wish to get a place," she said, "you must be quiet and respectful in your manners. If you sit down a bit, we may have other ladies in."

Peggy took a seat in silence. She saw a good deal of coming and going, was interviewed herself by a publican's wife, a grocer's, and a young bride just married to a plumber and gasfitter, but she calmly declined each of these situations, asserting gravely—

"I means to live in a proper house, in a real good place."

Then the Miss Shipleys lost patience with her.

"You tell us you have had no experience, and have never been out before. You ought to be thankful to any one for being willing to take you and train you. You bring us no references, and yet expect to get a first class place. It is quite ridiculous. You are really too small and young to be in service at all."

Peggy felt dismay for the first time, but she sat still in her corner. Other servants came and went, but she did indeed seem to be the smallest of them all. Presently, with a sigh, she got up.

"P'raps I'll call again to-morrow," she said. "There must be some nice places goin', and I means to get into one of 'em!"

She made her exit very quietly. The Miss Shipleys seemed rather relieved to get rid of her.

Once outside, big tears came to her eyes.

"Peggy, you ought to be 'shamed of yourself, great cry-baby! You've got your clothes, and of course you'll get a place."

She rubbed her eyes vigorously, and was startled when she heard a lady's voice close to her.

"What is the matter, little girl? Can't you get a place?"

Peggy looked up astonished, not knowing that her words were overheard.

A lady dressed in mourning was addressing her, and Peggy thought she had one of the sweetest faces that she had ever seen.

"Oh, please 'm," she cried, "do you want a servant? I'd like ever so to come and live with you."

The lady smiled. "I am just going in to the Registry for a girl, but I think you are too small."

"That's what they say," said Peggy, with a little gulp in her throat. "And if they only knew what I can do! I can scrub floors, and clean grates, and make beds, and clean winders—"

She rattled off the list of her accomplishments with hope once more shining in her eyes, as she saw the lady's interest in her.

"And, please 'm," she hurried to say, "I don't mind if you don't have a garding; but I'd do for you faithful wherever you be."

"We can't well talk in the street," said the lady. "Come inside. I will ask Miss Shipley about you."

Peggy followed her in with bright eyes and red cheeks.

"We don't know anything about her, Miss Churchhill," said Miss Shipley when questioned. "She appeared about an hour ago. We wonder if she is quite—well, quite bright!"

The lady looked down at Peggy's eager face.

"Not much the matter there," she said, with a smile.

"The fact is, Miss Shipley, we are giving up our town house, and my sister and I have taken a small cottage in the country. We thought of taking some respectable girl down with us."

"Oh, please 'm," broke in the irrepressible Peggy, "'tis the very place for me. Mrs. Creak says the country is so clean, and I'll have to be awful careful with my caps and aprons. Oh, please try me, and see if I don't soot you."

Miss Churchhill smiled again, and then questioned her closely as to references. The interview ended in Peggy leading the lady straight to Mrs. Creak's sweet-shop.

"Mrs. Creak will tell you all about me 'm. And she knows what good service is, for she lived in a Rectory. I s'pose 'm, you haven't a Rectory and a church belongin' to you!"

Miss Churchhill's eyes grow moist.

"I have known what it is to have a church belonging to me," she said gently. "My father was in charge of one in the East End, and died from overwork only a month ago."

Peggy nodded sympathetically.

"I've had a death belongin' to me, too," she said. "'Tis awful! 'Twas my aunt, and now I've no one left."

When they entered the shop, Miss Churchhill asked Peggy to wait outside.

"I want to have a private talk with Mrs. Creak," she said.

Peggy trod the pavement outside with firm steps.

"You've done it, Peg! You've found yerself a place with a real lady, and it has been as straight and easy as anythink!"

Some acquaintances accosted her.

"'Ulloo, Peggy, goin' to church on a weekday?"

"'Ave you bin to a treat?"

"I'm a-goin' into service," said Peggy, with uplifted head.

"Oh, you por critter!"

Then they danced round her singing—

"Worked in the army, worked in the navy,

But most worked o' all is the poor little slavey;

Cookin' and scrubbin', dustin' and runnin',

Missis is allays a-beatin' and scoldin'!"

Peggy turned upon them furiously.

"You keep your tongues quiet. I'm a-goin' to the country, I am! When you gets taken for a day's 'curshion, you think o' me! Not pickin' flowers and eatin' apples and blackberries one day in the year, but all the year round, all day long, I'll be doin' it! I shall live in a hop-garding orchard, and never want no dinner off sassages or herrins, for I shall eat strawberries and plums and grapes till I got quite a tired o' their taste!"

"Go it, Peg!" cried out a small boy. "And where be yer goin' to live? In a carawan?"

"In a white house," went on Peggy waxing warm in her enthusiasm, "with walls covered with roses, and a green door; and vi'lets, and lilies and chrysanthys all over the garding, and a pond with swans, and a fountain—"

"Garn wi' yer!"

A piece of mud was flung at her. Peggy beat a hasty retreat, and tumbled into the arms of Miss Churchhill.

"If you please 'm, may I come?"

"I am going to see your Sunday school teacher. I know her slightly. Mrs. Creak gives a good account of you, Peggy, but you see Mrs. Creak is quite a stranger to me."

"She's real good 'm, Mrs. Creak is."

"I have no doubt of it. I will write to you after I have seen Miss Gregory. Good afternoon, Peggy."

Miss Churchhill walked away, and Peggy darted into the sweet-shop, where she stayed for half an hour talking over the wonderful fortune that might be coming to her.

COUNTRY MUD

IT was a mild afternoon towards the end of February. Sundale Station looked deserted when the London train dashed into it. Only a porter stood on the platform to welcome any arrivals, and when the one passenger proved to be our Peggy, hugging her small box, he looked at her with grim humour.

"I'm paid by the Company to wait on you, Miss, so hand over. Where are you going? Not from this part, are you?"

"I'm going to my place."

Peggy was in nowise daunted.

The journey had been a delightful one. Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Creak had both stolen a short respite from their busy life to come to the station and see her off. She had received a parting present from both of them. Mrs. Jones had presented her with a fancy workbox, gay with painted flowers, and Mrs. Creak a stout serviceable umbrella.

Peggy thought there never was such a happy girl as herself; not a shadow dimmed the future. And she looked up into the porter's face now with such a beaming smile, that an answering one appeared on his.

"Well, where's that?"

"Ivy Cottage—Miss Churchhill's."

"Oh, those be the two fresh ladies come down last Monday. You wait a bit, and I'll get my barrow and go with you. 'Tis only half a mile—a little more."

So a quarter of an hour later Peggy stood before her new home. Perhaps it did not quite come up to what her fancy depicted. It was a small red-brick house standing back from the road, with a front garden edged with trees and shrubs. Straw and newspaper littered the front path, the windows were curtainless and blindless, and the front door stood open, showing furniture blocking the way.

Peggy walked up the path with smiling assurance; then she paused, for down on the floor, at the foot of a flight of steep narrow stairs, sat Miss Churchhill, with dishevelled hair, and a handkerchief up to her face.

When she saw Peggy she sprang to her feet.

"Why, Peggy, we have completely forgotten you! Come in. Is this your box? How much is it? Sixpence. Thank you, porter; put it down here. We are all in confusion. Good afternoon. Now, Peggy, you must help us, for we hardly know what to do first, and I am in the agonies of toothache."

She tried to speak brightly, but Peggy's quick eyes rested on her face.

"Please 'm, you've bin cryin'. I'm wery sorry for yer; but, please 'm, have you tried brown paper and vinegar with a little pepper? Aunt used to find it eased her faceache wonderful, and Mrs. Jones, please 'm, used to soak her brown paper in gin. She said it was first-rate."

Miss Churchhill began to laugh; Peggy's interest and earnestness when she had hardly set foot inside the house comforted and cheered her.

"Joyce!" she cried. "Our little maid has come."

Downstairs came a bright-faced dark-haired girl. She had an apron over her black dress, and her skirt was pinned up. She smiled at Peggy.

"There's a lot to be done, so you must help us as quickly as you can. The woman who has been cleaning for us had to leave early to-day. We have got your room ready. Can we get your box up? It is quite a small one; you take one handle, and I will take the other."

The little room was soon reached. Peggy gazed at it with admiration, but her eyes remained longest on her dressing-table and looking-glass.

"I was a-wonderin' whether I'd have a glass," she said confidentially to the youngest Miss Churchhill. "You see 'm, it's rather partic'lar to me, 'cause of my caps!"

"Oh, of course," Joyce replied, hastily beating a retreat; "now take your things off, and come downstairs as quick as possible. It is tea-time."

"My dear Helen," she said, when she joined her sister, "what an extraordinary specimen you have got hold of."

"She is an original, but I'm hoping she may be a treasure. Don't laugh at her, Joyce; she takes life in real earnest. She has done me good already. I was feeling so miserable when she arrived."

"Poor old thing! You're worn out. Shut the front door, and come and sit down. We shall all feel better after a cup of tea. Do you hear the kitchen fire crackling? Doesn't that cheer you up?"

"We shall never get our furniture into the rooms," sighed Helen. "We ought to have sold more, and brought much less."

"I shan't speak to you till we've had tea!"

Joyce went off to the kitchen, singing; then a few minutes after came back to her sister.

"We haven't a drop of milk in the house. I've forgotten all about it."

"The farm is close; send Peggy."

"So I will."

Joyce ran upstairs. She found Peggy holding out one of her print dresses, and gazing at it with loving admiration.

"I'm just a-goin' to get into it, please 'm."

"Oh, you needn't do that to-night. Slip on an apron. But I want you first of all to run up to the farm for some milk. I will show you where it is. Put on your hat again, and make haste."

Peggy breathlessly obeyed.

Joyce took her outside the gate, and pointed to another large gate on the opposite side of the road.

"Go through that, and keep to the footpath across the field; then go through another gate, and you'll reach the farmyard. Get a pint of milk from Mrs. Green, the farmer's wife, and tell her who sent you. She'll know then; and it will be all right. Do you quite understand?"

"Yes 'm."

Peggy departed with pleased importance.

She was a long time gone, but at last she reappeared with a very sober face.

"Come along; where's the milk?" asked Joyce, meeting her at the front door.

"Please 'm, I haven't got it!"

"Why? Have you spilt it? What is the matter?"

For answer Peggy slowly pulled up her skirt, and displayed one boot, which she raised in the air for inspection. It was certainly very muddy.

"I had to turn back 'm. It was awful! I never see'd such mud—never! It ain't like the mud I've bin accustomed to; it sticks! And it got worse, and a cab-horse wouldn't a-walked through it!"

Joyce stared at her, then lost her patience.

"You stupid girl! It's no good to be afraid of mud in the country. Here are we waiting for our tea! How do you expect us to get our milk? If you don't do it, I must."

Tears that had been very near the surface now ran over.

"Please 'm, it's my best boots, and they cost four shillings and sixpence; but I'll try again 'm."

Peggy choked down a sob, and departed.

Joyce went back to her sister half-amused, half-vexed.

"She thinks no end of her clothes," she said. "If she could only see what a little guy she looks!"

"Oh, hush, Joyce! I don't think she is half bad-looking. She is very thin, and has that stunted, wizened appearance that most London children have, but she has a dear little face. It will be getting dark if she does not make haste. I never should have thought that mud would have turned her back."

Poor Peggy was going through worse horrors than mud, and when she finally arrived with the milk, her hat was awry, her black dress was covered with dirt, and her eyes nearly starting out of her head with terror.

Joyce snatched the jug out of her hand, and marched off to the kitchen without a word; but Helen took pity on her.

"What is the matter, Peggy? You look frightened."

"Oh, please 'm, I've never bin to a farm, and I did go through the mud, though it was almost a-drownin' of me, and then I come to a gate, and when I got through, please 'm, it was a wild beast show, only worse, for they weren't shut up in cages! There was great brown bulls with 'orns 'm, a-tryin' to run at me, and there was pigs as big as sheep, and great white geese, and a dog barkin' like mad and tryin' to break his chain to get at me, and awful-lookin' turkeys which I've never seen alive 'm before, only hung up in shops at Christmas-time, but I knewed 'em by their red beards, but the scandalous noise 'm they made at me, would frighten the king hisself!

"They all made for me 'm, they did indeed, and there was ducks and fowls by the hundreds all runnin' under everybody's feet. Please 'm, I knewed I were in dreadful danger, but I did my dooty faithful, and thought of your milk. Only what with the sticky mud, and the cocks and hens, and tryin' to dodge the bulls, and turkeys, and all the rest o' the wild animals, I fell slap down 'm, and then I give myself up for lost. I 'ollered, and 'ollered, and then a man run out, and he took the jug, and was so kind as to tell me I might wait outside the gate, and he fetched the milk to me hisself.

"And, please 'm, is there no p'lice in the country, for they wouldn't allow no such goin's-on in London; they be all on the loose and no one to keep 'em from attacking yer! And, please, 'm, must I go every day to fetch the milk?"

Peggy's breath gave out. She truly had been nearly frightened out of her wits.

Helen concealed her amusement, and spoke very kindly.

"We forgot you were a little town girl, Peggy. We will not send you till you are accustomed to country ways. I don't think the animals would have hurt you, but I'm sure it must have been very alarming. Now go upstairs and change your boots, and brush your dress, and then come down to tea."

Poor Peggy went upstairs a sadder and a wiser girl. She shook her head at herself in the glass.

"Yer clothes will be ruined, Peg, and you've no more money to buy new ones. I almost thinks I shan't like the country."

But a minute after, the glory of perching her cap on the top of her head, and feeling that it had a right to remain there, overcame all her woes.

She went downstairs with a smiling face, and when she found herself in a cheerful kitchen, which, though small, was tidy, she again congratulated herself on her good fortune.

Joyce found her really helpful in getting things to rights, and when she laid her head on her pillow that night, Peggy added the following to her evening prayer:

"And, please God, I thank you for bringin me 'ere, and making me into

a proper servant. And I'll try to do my dooty to you and my missuses. And

please help me to do it, for Jesus' sake. Amen."

Perhaps the supreme moment to Peggy was that in which she stood arrayed the next morning in her clean print gown. What did it matter if it was faded and old? It was starched, and crackled when she moved.

"Sounds like silk almost," she said to herself; and she certainly swept downstairs as if she were a princess robed in satin.

Poor little Peggy had never before possessed a dress that had to be washed. When water was scarce, and soap and soda had to be considered, it was natural that she could not afford the luxury of a dress that soiled so easily. A girl going to her first ball could not have taken more care not to spoil the dainty freshness of her gown, than Peggy did of her second-hand print dress that morning.

Joyce, coming down to help with the breakfast, returned to her sister upstairs exploding with laughter.

"Helen, your little maid will be the death of me!"

"What has she done now?"

"She has pinned newspapers all over herself to preserve her gown and apron. She looks like a walking edition of the 'Times!' And when I remonstrated, she said the coals and kitchen grate would soil her clothes. Can't you hear her crackling as she moves about?"

Helen laughed heartily.

"Don't hurt her feelings. I don't think she has ever possessed a cotton frock before. She will soon get accustomed to it, and, after all, such extreme cleanliness ought to be encouraged."

In a few days Ivy Cottage presented a tidy aspect. Helen and Joyce felt that their rooms, if tiny, were cosy and even pretty. And Peggy's gratification was great when the stairs were carpeted. She took a keen interest in her new surroundings and learnt to use the possessive case pretty freely.

It was "my kitchen," "my kettle," "I'm sweepin' my draw'n' room," or "dustin' my dinin' room bookcase." Everything—upstairs and down—belonged to her, and "my house, my garding, and my missuses" formed the chief topic of conversation with any passing villager. She found she had a great deal to learn, but she was so willing and anxious to please, that Joyce, who took her in hand, forgave her ignorance and awkwardness, and prophesied to her sister that though at present a rough diamond, she might prove worth her weight in gold.

Mrs. Creak meanwhile looked out anxiously for Peggy's first letter.

The Board School had certainly taught her to read and write, and though the letter arrived with many an ink-smudge and blot, it was quite decipherable.

"MY DEAR MRS. CREAK,—I'm going to write to you for this is Sunday and

I've been to church, and I let you no that the cuntry aint clean at

all, but downrite filthy, for I never seed mud like it in London. There

is no lamps or shops when tis dark so you falls down anyweres in a

ditch or pond and no pleece picks you up for there is none of them.

"Old men wears their shirts over their coats to come to church. Farms

has hunderds of feerce animals kep roun them which you has to walk

thro, and they all tries to kep you away from the door, and cows and

bulls walks along the road all day. There is no shops noweres.

"My place is fine and I has butter to eat evry day. I has many

hunderds of things to take care of. I treds on carpets evry day.

I spilt tea over my apron I trys to be clean. There is more to dirt me

than our room in London. My missuses are nice ladys. I am quite well

as I hopes it leaves you at present.

"Your friend,

"MARGARET PERKINS.

"P. S.—Nex Sunday I goes to Sunday School. Please give my love to

Missus Jones."

"Well," said Mrs. Creak, folding up the letter and taking off her spectacles, "girls is different to when I was young! The country too dirty for her! What next! Nought about the sweet, pure air and blue sky and singing birds, and green grass and trees and hedgerows. Her eyes never gets higher than the mud! I'm ashamed on her, that I be!"

"TOO FAITHFUL"

"PEGGY, Miss Joyce and I have to go away for a night. We are wondering about you, but Mrs. Timson, our next neighbour up the road, has kindly said she will let you sleep at her cottage. In fact, I think we had better lock up the house, and you go to her altogether."

But this did not suit Peggy at all. Here was an occasion to prove her trustworthiness!

"Oh, please 'm, I've a lot o' cleanin' to do. I would be ever so careful. Miss Joyce has showed me how to clean my brass fireirons, in my drawin' room, and I wants to scrub out my cupboards, and I has two aprons to wash, and, please 'm, there ought to be some one to take care of the 'ouse, 'cause of burglars!"

"We are not afraid of burglars down here," said Helen, with a smile. "And there is 'Albert Edward'; he can be tied up to guard the place."

"Albert Edward," was a new importation. He was a rough-haired terrier that had been presented by the vicar, and he was a formidable watch-dog. Peggy and he were great friends, and they had many mutual likes and dislikes.

"Yes 'm, Albert Edward and me will take care of everything beautiful."

In the end a compromise was made. Peggy was allowed to stay in the house till four o'clock in the afternoon, then she was to go to Mrs. Timson.

She stood at the gate a proud and happy girl when her mistresses departed the next morning. She watched them out of sight, then stayed a minute in the front garden, gazing at a clump of snowdrops, the only flowers then in bloom.

Mrs. Creak was wrong when she lamented Peggy's non-appreciation of the beauties of nature.

Her little soul was drinking it in very slowly, but very surely.

As she looked out of her small bedroom window every morning, she would say to herself—

"Oh, Peggy, what is it makes you feel so happy? 'Tis the wonderful lot of room you sees, and all the empty earth and sky, why all London couldn't crowd out this place, 'tis so big!"

Now as she looked at the snowdrops, she addressed herself again.

"They does keep theirselves clean, Peggy. 'Tis a pity you can't be more like 'em, they be just like white chiny. I'm glad I don't have to dust 'em ev'ry mornin'. I should be certain sure to snap their stalks off! I wish Mrs. Creak could see what flowers I have 'ere, and nothink whatsoever to pay."

Then she betook herself indoors.

The garden was pleasant, but she could not scrub or dust it, and those two arts were at present her chief joy.

The day passed too quickly for all she had to do, and at four o'clock she locked up the front door, leaving Albert Edward in the back kitchen with a plate of scraps by his side.

When she arrived at Mrs. Timson's she found that worthy woman sitting down with her husband at his tea. John Timson was the carrier to the nearest market town, six miles away. He was a meek little man with a great faculty for receiving all local gossip and quietly passing it on.

His wife overpowered him when present. She was a head taller than he, and a great talker, but not a cheerful one. They had no children, and Mrs. Timson was very glad to help out their small income by going out cleaning or washing. She washed for the Miss Churchhills, and Peggy's much-prized cotton gowns passed through her hands.

"Come ye in and sit down, me dear," she said to Peggy. "I've been expectin' ye this long while. How's the world treatin' ye? Better 'n it do me, I reckon! For 'tis work, work, work, when me bones is full of aches and pains. And if I had laws to make, I'd make 'em so as to make the sufferin' ones sit still, and the hearty ones to work."

Her husband gave a quiet wink to Peggy.

"Meanin' me, in course, wife; but I do be at it all day long."

"You? You sit in your cart like a dook, and gossip wi' folks till one don't know fac' from fiction. 'Tis me that be at it all day long."

"I like workin'," said Peggy simply. "But then I be stronger than you, missus."

"That you be. I mind when I were a girl how I worked. But there! Things is different nowadays, and I'm gradorly droppin' down towards me tomb."

"I've locked up," said Peggy inconsequently. "Do you think it will be all safe?"

"Safe as my watch in my pocket," said the carrier.

His wife shook her head at him.

"Do ee remember that terrible murder away at Ball Farm two years gone? 'Twas a farm servant left in charge, and 'twas gipsies that did it. Two men got inside, dressed like women, and they were purtending to tell fortunes, and the poor little maid screamed for help, and they killed her."

Peggy's eyes grew round. She was accustomed to London horrors, but she thought the country was free of them.

"I ain't afraid of no one with Albert Edward," she said sturdily. "I'd like to have slep' by myself over at my 'ouse to-night. Albert Edward would kill any burglar if he could get at him, I know he would."

Once embarked on a gruesome subject, Mrs. Timson flowed on, bringing out of her past reminiscences so many ghastly stories of murder and thieving and such-like, that at last her more cheerful husband interfered.

"Come, missus, stop it! This young lady won't sleep to-night. She be drinkin' it all in like water!"

"Oh! I ain't afraid," Peggy again repeated. "I arsks God to keep me safe, and I knows He will."

Her sleep was sound and sweet in spite of Mrs. Timson's stories, and she would hardly wait for her breakfast, so impatient was she to get back to Ivy Cottage.

"My missuses will be back at three o'clock, and I has my rooms to sweep and dust, and Albert Edward will be expectin' of me."

She ran back with a light heart, found the postman had left two letters, but no one else had disturbed the premises. She worked away with a light heart, but at twelve o'clock heard at sharp ring at the bell, and when she went to the door was confronted by a tall commanding-looking lady, who asked gruffly if the Miss Churchhills were at home.

Now the last words of Miss Churchhill to Peggy had been these—

"You are to let nobody into the house, Peggy. You cannot be too careful. If any one calls, say we are away from home."

So, with a suspicious glance at the visitor, Peggy replied importantly—

"My missuses be away till this arternoon."

"How vexing, to be sure! But they must have had my letter. I will come in and wait. My bag is at the station, and will follow me."

Peggy's head was so full of the stories that she had heard, that she murmured to herself—

"Tis a burglar, Peggy, a-dressed up and tryin' to get in. Now be brave, and do your dooty."

She slowly began to shut the door.

"No 'm, I ain't goin' to let you in; and if you don't get off with yer pretty sharp, I'll call Albert Edward!"

"You impertinent girl! Do you know who I am?—Miss Alicia Allandale. How dare you try to shut the door in my face! A nice reception when I come to see my nieces! Let me in this minute!"

Miss Allandale had a stronger arm than Peggy. As she found she could not close the door, she called loudly to Albert Edward. Alas! He was already barking frantically in the back kitchen, with two closed doors between him and the intruder.

"You go out this minit!" Peggy shouted valiantly. "I see yer tricks. You ain't a-comin' I tell yer, so there. Not if I dies for it!"