Title: Luke's wife

Author: Evelyn R. Garratt

Illustrator: Francis M. Parsons

Release Date: September 4, 2023 [eBook #71564]

Language: English

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

CHAPTER

VII. RACHEL CONFIDES IN THE BISHOP

VIII. THE BISHOP COMES TO LUNCH

XI. THE CHOIR THREATEN TO STRIKE

XVIII. GAS STOVES VERSUS MOUNTAINS

XIX. GWEN WRITES TO THE BISHOP

XX. NO LADY HEAD OF THE PARISH

XXI. THE BISHOP LOOKS INTO THE KITCHEN

XXVI. LUKE TELLS RACHEL ABOUT HIS DREAM

XXIX. IN THE LIGHT OF THE MOON

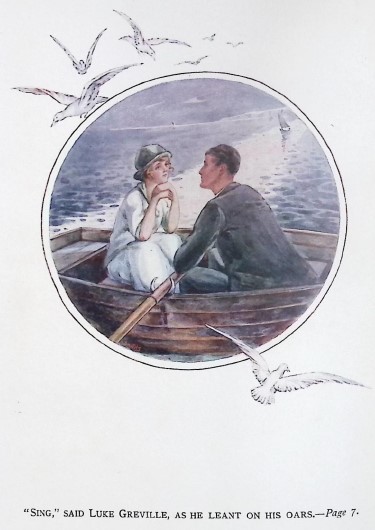

"Sing," said Luke Greville, as he leant on his oars and looked at his wife sitting in the stern of the boat.

And Rachel sang.

The boat lay almost still in the silver pathway flung by the moon across the sea. There was scarcely a ripple.

Rachel's voice trembled a little when she began to sing, as a sense of mystery and wonder enveloped her. The dark sea beyond them; the earnest face of her husband lit up by the moonlight; the fact that they were quite alone on the vast waste of water, combined to fill her with awe and to make her voice a little unsteady for a moment.

Her singing thrilled her husband as he sat listening. His dream had come true; and this last evening of their honeymoon they were alone on the sea; in quiet; with God.

Rachel sang; and these were the words that she sang:—

"And love is God, and God is love,

And earth beneath and Heaven above

Are swathed in it and bathed in it;

For every flower of tender grace

Hath God and Love writ on its face,

And silver shining stars on high

Spell Love and God across the sky."

When the last note of her song trembled away across the waters, there was silence between them while they looked at one another as only those who love and trust can look. Words were not needed between them. They were so absolutely united in spirit that outward expression of their love was unnecessary.

Then Luke took up his oars and rowed vigorously towards land.

"All things must have an end," he said, "even the happiest honeymoon that was ever spent. I suppose we must go back to our rooms."

"Must we yet? Let us stay out till the last minute. Perhaps we shall never have such an evening again together, with the moonlight on the sea."

"We'll come here next year," he answered laughing, "and after a year of happiness it ought to be better still. Why are you pessimistic?"

Rachel was silent for a moment, then she said, "I'm afraid of your work."

"Afraid? Why?" He leant towards her in surprise.

"Because I have a feeling that it will take you from me," she answered. She knew perfectly well by this time that his work was his passion. The thought of it had at times absorbed him even during their days of bliss. They had been so happy together, almost like light-hearted children, but Rachel had noticed the last few days that his parish and his people were engaging many of his thoughts and that he was getting a little restless. If his work weighed on his heart even during his wedding tour, thought Rachel, was there not a fear that it would be pre-eminent in his thoughts when in the midst of it, to the exclusion of her?

Luke laughed at her fears, and after a few moments remarked, "There is only one thing I regret and that is that I am not taking you to a comfortable Vicarage. I don't mind a small house myself nor did my mother, but I'm afraid you will feel cramped."

"But they are going to build a vicarage soon," said Rachel.

"They will be a good time about it, I fear. You see the Parish has only just been divided, so it is not in proper working order yet; besides which, I think it may be as well for us to live in a small house, anyway at first. A Vicarage means a certain amount of expenditure not to mention dilapidations. Nevertheless I am sorry that the home I am taking you to is not larger. But after all we don't want to live in the lap of luxury. We are out to fight the great enemy of souls, you and I, and we can do that as well in a small house as in a large one. Perhaps better."

"How I wish I were more capable," sighed Rachel; "I don't know anything at all about Parish work. You ought to have married someone very different."

Luke laughed.

"It's too late to give me that advice. And let me tell you that I prefer a wife who comes to the work fresh, rather than one who is already tired and perhaps discouraged. I said so to my mother."

"I am afraid that your mother would not agree. Did she feel leaving you very much? And are her rooms close by?" Rachel listened for the answer rather anxiously.

"She was wonderfully unselfish about leaving the coast clear for you; but her rooms are not far off. You will soon love her."

"I am sure I shall make no end of mistakes," sighed Rachel, a little depressed at his answer.

"Don't you know that it has been said that a person who makes no mistakes makes nothing else?"

"Yes; but—" she paused, then she suddenly changed her mind, saying—

"Let us forget everything for a moment but the moonlight on the sea, and that we have one another."

Luke rested on his oars and the moon shone down upon their faces alive with love, as if it blessed them.

Rachel leant back in the railway carriage and watched the fields and hedges rapidly passing. But her thoughts were far away. She was going home, but not to the old familiar place she had hitherto called by that name. It was to her new home, and the life that she was to spend there was all untried.

She could not but remember the welcoming smile that her mother always gave her even when she had returned only from a walk among the hills. She knew that whatever new interest might come into her mother's life that she would never cease to think first of her children. She had always made everything subservient to their interests and welfare. Before she became an invalid she had never allowed social or any other claims to interfere with theirs, and since she had had to lead a semi-invalid life their interests had still been hers, their joys and sorrows were felt to be her own.

And now, Rachel would have to make her own way in her new world; and have no mother to fly to in any of her difficulties. Her mother-in-law would certainly not take her place, although Luke had talked of her with complete satisfaction and the greatest love. His mother, in his eyes, was everything a man could wish for. She was apparently perfect. But Rachel had not liked what she had seen of her at the wedding, and felt intuitively that she was not approved of by Luke's mother. Luke was evidently her idol, and no-one could be good enough for him. The few remarks she had exchanged with Mrs. Greville had convinced Rachel that Luke's mother had hoped for another kind of wife for her son; one who was used to Parish work, and capable of managing people. Rachel had told her at once that Parish work would be a new experience and had said a little wistfully that she wished she had done more than she had for their home parish. "But I had mother to take care of," she had added.

"Yes," Mrs. Greville had answered, "it is rather a pity that you have had no experience in that line. I am afraid you will find it difficult."

And Rachel had added almost against her will, "And unfortunate, I am afraid, for Luke. However, I can always learn, I suppose."

Mrs. Greville had looked at her with cold critical eyes, saying, "We can learn anything if we put our mind into it," and thought as she uttered the words, "I only hope she will be useful as well as ornamental." The unspoken thought was so evident in the glance that Mrs. Greville gave her, that for a moment, even though Rachel had just been married to the man who was all the world to her, and for whom she was forsaking her mother and her home, she turned away feeling hurt, and vexed.

It was the thought of the mother-in-law who she would have to meet when she arrived in her new home, that was the cause of the slight feeling of depression and fear of which she was conscious as the train neared its destination. Then she glanced across at her husband.

He was deep in the "Times" and apparently utterly unconscious at the moment of her presence. But the expression of great content and interest on his face, and the sudden laugh that escaped him as he handed the paper across to her to enjoy with him something that had tickled his fancy, drove all depression away. After all she had him—for ever—that is to say till death should part them. What could she want more? And she had not promised to like, and adopt, his mother as hers!

It rained during their railway journey, but as they reached the manufacturing town in which was Luke's Parish, the sun shone out, and it was a happy pair that at last drew up at the door of the little house that was to be henceforth home.

"Here we are," exclaimed Luke as he handed out his wife. At the same moment the door was opened by a minute person with a short frock and white apron and with a little cap perched on her head. She looked at them with a broad smile.

"Who is the child?" asked Rachel.

"Why it's Polly Green! My mother promised me that she would get us a really nice little maid; and I know Polly well. She is a thoroughly nice girl. She then, is to be our factotum."

"Well Polly and how are you?" he said heartily, as he gave the bundle of umbrellas into her hands. "This is your Mistress, and you are a lucky girl to have her. Now be sharp, my girl, and put the umbrellas in the hall and then come back for another parcel."

Rachel laughed almost hysterically as she watched Polly running about with her cap on one side and then opening the door of the sitting room with an important air. She had never contemplated for a moment having such a small factotum!

As she stepped into the little room, the door of which had been opened by Polly, she laughed again. It was so very small! Luke had given her no idea at all of its dimensions. He had merely said he could trust his mother to see after the house and to make them comfortable. His joyous laugh as he followed her into the room mingled with hers.

"I'm glad my mother has secured Polly for our maid," he said. "She is a first-rate little woman and always answers the Scripture Questions better at school than any other girl. She'll do well for us."

Rachel did not quite see how answering Scripture questions at school made her fit to be a little maid of all work! But it was all so surprising that she looked around merrily.

"It's almost like a fairy tale," she said, and the thought flashed across her mind, "like a doll's house." Then it was that as Luke suddenly glanced at his wife a feeling of apprehension seized him.

Rachel was standing looking at the pictures on the walls, and her radiant beauty and lovely clothes struck a cold chill into his heart. She looked out of place! And he felt his home must appear to be dull and uninteresting.

"I am afraid," he said, putting his hand on her shoulder, and his tone of voice was tinged with regret, "I am afraid that it must strike you as very different from what you have been used to. The house is so small."

"I like it small," she answered cheerfully, "for even when you write your sermons you will not be able to get away from me. I like it to be different."

She had seen at a glance that the wall paper was ugly, the furniture badly arranged, and was not surprised to hear that both had been his mother's choice. It was exactly the kind of paper and furniture that she would expect her to choose. All good, but nothing dainty. But what did it signify? She could have the room papered by-and-bye, and get rid of some of the furniture, and would soon be able to make it homelike and pretty. And after all it did not matter having to live with hideous furniture and drab wall paper if by so doing she had Luke to herself, and was able to help him in his work.

Somewhat assured by her answer and bright smile, Luke led her into the drawing-room, a still smaller and duller room at the back of the house, looking on what, by courtesy, we will call a garden, but was nothing more than a yard containing a few sad looking bushes and a sickly flower or two. Polly appeared asking with a broad grin when she might "serve tea."

"What have you got for tea?" enquired Luke, thinking of Rachel.

"Mrs. Greville brought round some eggs, Sir," answered Polly.

"Good, we'll have them. And I suppose there is jam?"

"There's a pot of plum jam, Sir."

"Bring that then and be as quick as you can Polly as I have to go out in half an hour."

"Go out!" exclaimed Rachel.

"Yes, I'm sorry to have to leave you your first evening," he answered, "but it's the Church Council and I must be there. I got it postponed till to-day as it should have been last Thursday. I am sorry dear."

Rachel smiled. She would not let him see her keen disappointment, nor know that the fear she had expressed to him the evening before gained ground by his words.

"I suppose," she said laughing, "that this is what I must expect, having married a clergyman."

"I am afraid it is! But we shall soon be working side by side and going about together. I shall want you with me. My only fear is that you will work too hard."

The picture he had drawn of them working together had cheered her.

It was at tea that Rachel asked if his mother was on the Church Council.

"No," he answered, "but she is on everything else. She is as good as a Curate. I can't tell you what she has done for me since I have been here. It has made all the difference to me having her. You will get to love her I know."

"I shall never love her," thought Rachel, "but I must try, I must for his sake, and he shall not find out if I can't."

Luke looked at his watch, and rose quickly. "I must be going," he said.

Left alone, Rachel tried to check a slight feeling of homesickness that attacked her. The room was so small and rather dark and yet it was scarcely time to light up. She flung the window open and stood by it looking out into the little yard with the sad looking bushes. Should she ever get used to her surroundings, she wondered, or would she always have the feeling, almost of suffocation, that she was experiencing this evening? It was all so different to her home in the country. From the drawing-room window at Heathland she could see a wide expanse of country and could even feel the wind that blew from the moors. It was not a large house but a thoroughly comfortable one, standing in four or five acres of land. They had lived in a much larger place, in Rachel's childhood, but her father dying, they had moved about ten years ago into what was called Heathland cottage.

Rachel had lived a life of perfect freedom, her only definite duty being that of taking care of her invalid mother. She knew nothing of housekeeping, her elder sister was the housekeeper, and as for cooking! She scarcely knew how to boil a potato.

She forgot that tea was still on the table, and was startled by Polly's voice asking her if she might take the tea things away, as she thought Mrs. Greville would be coming in by-and-bye, and would not be pleased to see them not washed up. Might she take them?

Rachel gasped at the remark. Was she then to be under Mrs. Greville's eye, or rather, was her mother-in-law to instruct Polly as to what to do?

Polly's words had the effect of arousing her from her dreams, and she set to work to help the girl to clear away, leaving her to wash up while she began to unpack. She earnestly hoped that her mother-in-law would not pay her a visit, but determined that she should find her ready to receive her should she appear.

It was rather late when Rachel made her way downstairs. The house was in darkness. But she heard Polly moving about in the kitchen.

"Why Polly, you are in the dark! You had better light up. You can't see to do your work."

Polly rather eagerly turned up the electric light.

"I didn't like to do it before Ma'am," she said, "as Mrs. Greville told me that I must be very careful not to waste the light as it is so expensive, and I thought if she came along and found it she might be angry."

"Well I'm your Mistress now," said Rachel, "and whenever it gets dark, I give you leave to light up. I'm sure you will be careful."

Rachel turned away and recklessly lit the three lights in the tiny drawing-room. She felt angry. Mrs. Greville should find that she had no authority whatever over Polly from henceforth. But the anger soon subsided, and apprehension took its place. Was her mother-in-law going to be a source of unhappiness in their home? But no, it was unthinkable, she must learn to like her.

She must not give place to the feeling of resentment which already was getting a hold on her. The day that Luke found out that she did not love his mother would, Rachel felt sure, be the beginning of an altered feeling in him about herself. It would disappoint him so terribly, and would be a continual source of worry. And she determined that she would never worry him.

And after all was it not very small of her to be so angry about such a little matter? It was much too small a matter for Luke to understand. She must try and take a broader outlook on life and not let little things affect her.

While these thoughts were engrossing her, the front door opened and Rachel heard a firm footstep which was not Luke's crossing the hall.

Mrs. Greville blinked as she opened the drawing-room door and faced the bright light. Her economical soul saw at a glance that all three lights were lighted, but she refrained from making a remark.

Loving her son as she did, she had come determined to make friends with his probably incapable wife, and knew that to remark at the very beginning on the reckless extravagance displayed, would not help her resolve. So she merely blinked, and for a moment shaded her eyes with her hand, saying, "My eyes are not used to such brilliance."

Rachel also had suddenly come to a determination on hearing her husband's mother's footstep. She recognised the fact that the future might depend on her present attitude towards Mrs. Greville, and was resolved for the sake of her love for Luke to make the best of it. She there-fore met her mother-in-law with a smile and outstretched hand. She was not quite prepared for the hearty kiss that was given, but she was pleased, as it seemed to put her in the right position of a daughter-in-law rather than as her son's unsatisfactory wife.

"How kind of you to come," she said.

"I promised Luke that I would do everything in my power to make his wife feel at home," answered Mrs. Greville, taking Rachel's hand and drawing her on to the sofa, "and when I found that he was going out to-night I was afraid you might be feeling a little forlorn; so I made up my mind to run round. I think he ought to have arranged better than to have a meeting the first evening."

The fact that Rachel had been conscious herself of a feeling of disappointment and of surprise that he should leave her so soon, made her wince at the words, and colour. Her pride was touched.

"But of course," she said, "he could not shirk his duty. He knew that I should have objected to him doing so." And as she made this remark, she imagined that she was saying the truth. So easy is it to deceive ourselves, particularly when our enemy pride is to the front.

"I'm glad to hear you are so sensible," said Mrs. Greville, "or I am afraid you would have to suffer continual disappointment. Luke's work is the first thing with him, and always will be. Neither mother nor wife will be allowed to come in its way. He is the hardest worker that I know. But just because of this he has to be looked after well."

"How do you mean?"

"Creature comforts are nothing to him. If he lived by himself I really don't know when he would think of food. If ever I went away for a week or two I found him looking shockingly ill on my return and generally discovered that he had not been punctual at his meals, and would have been quite happy to have gone without them altogether. You will have to look after him Rachel. By-the-bye, what did he have for his meal before going out?"

"You kindly sent round some eggs."

"Ah yes. Of course there was no time to cook anything else. But you will have to be careful about the eggs. They are 4d each at present. And," she added warily, "if I were you, my dear, I should not burn more than one light in this small room. Three are quite unnecessary. Electric light is extremely expensive unless you are careful. Of course you know that you ought to put it out every time you leave the room, even though it may be only for a minute or two."

"No," said Rachel, "I don't know anything about electric light. We used lamps at home. Is it really necessary to be so careful? I don't want to be always thinking of money." She gave a little laugh, but happily Mrs. Greville did not recognise the scorn in the tone of voice or in the laugh.

"Yes indeed, it is necessary, that is to say if you don't want to pay a big bill. My son is not a rich man."

To Rachel who had never had to think of these matters, the restrictions that were being laid down seemed absurd. She scarcely knew whether she felt more inclined to be angry or to laugh. She turned the conversation by asking if Polly could cook.

"No," said Mrs. Greville. "You will have to teach her. She is a very quick little girl and will easily learn."

"I am afraid she will learn nothing from me," said Rachel, "Could we not have had some older servant under the circumstances? I think I shall have to go to a registry office to-morrow. Which is the best one?"

"Servants are very difficult to get and I don't suppose that you and Luke could afford a really good one. No, your wisest plan is to keep on little Polly, and I will come round and teach you both. I will bring a cookery book with me and mark the most economical dishes for you."

"Thank you," said Rachel, faintly. The prospect was not exhilarating, but she knew the proposal was made in kindness, and after all both she and Luke must have food, specially Luke apparently! Her spirits were sinking to zero.

"And now I shall leave you," said Mrs. Greville rising. She glanced at Rachel, and noticed that she was looking tired and not particularly bright, so she added kindly, "Don't worry. It seems strange at first, no doubt, but you will soon get into our ways. You look as if you needed a night's rest after your journey. I hope Luke will not keep you sitting up for him to a late hour. He forgets everything when he is interested in his work. I shall have to give him a hint that he must go slowly for a time, and consider his wife."

Rachel flushed. The idea of his mother telling him of his duty to his wife was repugnant in the extreme. She could not endure the thought. It hurt her pride.

"Please do nothing of the sort," she exclaimed. "I don't wish Luke to come home a minute earlier for my sake. His work must come first."

Mrs. Greville not knowing how her words had stung her daughter-in-law, and being quite unconscious of the storm that she had raised in her heart, gave her a warm kiss as she left, saying, "That's right. That is the way to keep Luke's love. I am glad to hear you give out your views like that. I was a little afraid you might not see things in that light, but be somewhat exigent. Goodnight. I know you will do all you can to help my dear boy in his work. And be sure you feed him well."

Rachel turned away, and put her hands up to her hot face. "I can't, I can't love her," she murmured. "I never shall. I've never met that type of person before. Oh! I hope she won't spoil it all!"

Rachel indulged in a few tears, and then set to work to think what she could give her husband on his return from the meeting. She went to look in the larder and found a good sized piece of cheese and some macaroni.

Evidently Mrs. Greville had thought of macaroni and cheese for their supper, but Rachel had no idea how to make it.

"We must have the cheese for supper Polly," she said. "Lay the table in good time and then if Mr. Greville is late you can go to bed. I'm going to finish my unpacking."

About half an hour later Polly knocked at her door saying, with a broad smile, "Mrs. Greville has just been and left two meat pies, Ma'am, and said I was to be sure to ask you to see that the master eats them both as he'll be mighty hungry; but I think you ought to have one of 'em."

Rachel laughed—how queer and surprising everything was—particularly Polly.

Polly went to bed at nine, and Rachel sat down to read and to wait. It was past ten o'clock before she heard her husband's footstep.

She ran to meet him at the door. He put his arm round her as after hanging up his hat they made their way into the dining-room.

"How did the meeting go off?" she asked.

"Excellently. And I had congratulations from all sorts of people on my marriage. They are arranging a large At Home in the Parish Room in your honour, at which I am told their congratulations are to take a more tangible form. They are wonderfully hearty people, and I'm impatient for you to know them."

They sat down to supper and Rachel found that she had no difficulty in persuading her husband to eat both pies. He was so engrossed with the account of the meeting that he never noticed what he was eating or that his wife had to content herself with bread and cheese. Neither did he question as to where the pies came from. In fact he was hardly conscious that he was eating pies at all! Rachel felt sure that it would have made no difference to him if he had had only bread and cheese like herself to eat. His enthusiasm for his work was as good as food to him. She loved him for it, but she wondered at the same time if he had forgotten that this was the first evening they had spent in their home, and she was conscious of a little pain at her heart to which she would pay no attention.

But suddenly he looked across at her as if he had just awakened to the fact of her presence, saying, "What could I want more! God—work—and you! It is all more wonderful than I even anticipated."

And Rachel registered a vow in her heart; "I will never worry him with my stupid fears and littlenesses, and I will pray night and morning to be made more worthy of him;" but her sensitive spirit did not fail to notice that "you" came last.

Rachel stood looking down at the sirloin of beef she had ordered from the butcher and which now lay on the kitchen table. She was rather dismayed at the size of it and wondered how it ought to be cooked. She was determined that Luke should be well fed so that his mother should have no excuse to accuse her of not taking proper care of her son.

Polly was upstairs doing the bedrooms, and Rachel was thankful that she was not near to see her perplexity. Then the front door opened and she heard Mrs. Greville calling her. Vexed at being taken by surprise, Rachel resolved to lock the front door in future. She went into the hall to meet her mother-in-law, closing the kitchen door behind her. Mrs. Greville gave her a hearty kiss.

"I thought I would just look round," she said, "to know if you would like any advice about dinner or would care for me to give you a lesson in cooking this morning. I am due at Mrs. Stone's at twelve to help her to cut out for the working party, but I can spare you an hour or so if you like. What have you got for dinner?"

"A sirloin of beef; and I thought of having a rice pudding, that is to say if Luke likes milky puddings. I see you have provided us with rice and tapioca."

"A sirloin! That will never do; it must be changed at once," said Mrs. Greville, making her way to the kitchen. "It is the most expensive part of beef that you can have. You and Luke won't be able to indulge in that kind of thing. You must remember that you are a poor parson's wife, and must cut your coat according to your cloth."

Rachel flushed and wondered if she would ever be able to call her house and her food her own.

"I'll take it round to the butcher;" said Mrs. Greville as she surveyed the sirloin. "He's very obliging, and I know he will change it for a piece of the rump or a little liver. Wrap it up in several pieces of paper and put it in a basket and I will take it round at once."

"But it's too heavy for you and it's raining."

"Never mind the rain. It must be done or Luke won't get any dinner and this is a heavy day for him. I'll come back in a few minutes and give you a hint or two about to-day's meal."

Rachel bit her lip. She could scarcely bear this interference, yet she knew she was herself to blame for it, as she was utterly incapable. But if only she could be left alone she would learn from her very mistakes; and why need Mrs. Greville always be reminding her of the necessity of economy. She was sure it could not be necessary: she ought anyhow to have had a good general at first so that she could have learnt from her how to do things. As it was she was not even allowed to order her own dinner.

But as she saw her mother-in-law leave the house with the heavy joint in the basket, her anger melted. She remembered that she was only trying to help her exceedingly incapable daughter-in-law, and after all, she needed to be told how to cook the beef she had bought. It was no use ordering a nice dinner for Luke if she could not cook it for him!

When Mrs. Greville opened the door again with her basket considerably lightened, vexation at her own incapacity had taken the place of anger in Rachel's heart.

"I'm afraid," she said, as she took the basket from her mother-in-law's hands, "that you must think that Luke has married the wrong wife."

Mrs. Greville smiled kindly. Rachel's sudden humility touched her and she was pleased.

"Well, my dear, you may make yourself easy as Luke anyhow does not think so. He is under the impression that he has married perfection, and we won't undeceive him. It is just as well for a man not to know that his wife is not so capable as he imagines. Besides which," she added, as she took Rachel's apron off the kitchen door and tied it round herself, "if you pay attention to what I am teaching you there is no reason why you should not be as good a cook as I am. But don't look so melancholy I beg of you, nor so dreamy. I must tell you that there is no time in the life of a clergyman's wife to dream. You will find that every moment is important if you mean to look well to the ways of your household and also to help in the parish. A Vicar's wife has very little time in which to play."

Rachel pulled herself together though almost every word that had been spoken seemed to hurt her. She determined to pay all attention to what Mrs. Greville was going to teach her, not only for Luke's sake but that she could dispense with the cooking lessons as quickly as possible.

"There now," said Mrs. Greville, after showing Rachel exactly what to do, "you'll get on I'm sure."

Then noticing a look of depression on the girl's face, she added kindly, "And don't be downhearted. Although you've been taught nothing of this nature, unfortunately, you'll soon get into it. But whatever you do don't allow yourself to get depressed. A man when he comes home, after a hard day's work and a great many tiresome people to satisfy, needs a bright face to welcome him. For his sake, my dear, be plucky and do all you can to make up for lost time. Why girls are not taught really useful things I can't imagine. However, matters are improving in that direction. By-the-bye," she added, as she stood by the front door, "it's the working party this afternoon and you'll be expected. Luke will tell you where Mrs. Stone lives. It isn't far, and if you are not too long over your dinner you'll just have time to get there. Mind you're not late. A Vicar's wife has to set the example of being punctual. Good-bye again, and I hope you and Luke will enjoy your dinner. You may tell him that it was cooked by his mother; that will give him an appetite."

Rachel felt all on edge and wondered how she could bear many more mornings like the one she was spending. Yet she was well aware that Mrs. Greville meant all she said and did in kindness. And now and then she had noticed quite a nice smile flit across her face. Yes, she must try to love her; but this type of person she had never come across. Somehow she had never imagined for a moment that the mother, whom Luke loved so devotedly, would be like Mrs. Greville. She could not but compare her with her own sweet pussy mother, with her low, musical voice. Then a great longing for her mother took possession of her, and she ran up into her room and locking the door gave way to a flood of tears.

But there was twelve o'clock striking and Luke might be coming in, anyhow his dinner would have to be ready by one o'clock, and she had a hundred and one things to do before going to the working party. She must look her best and be her best.

She rather anticipated the working party. For one thing it would be her first appearance at a Parish meeting and she felt on her metal. No doubt she could get a little fun out of it. The prospect that Mrs. Greville had held out to her of a life without any time to play, had sounded dull, and she determined that the description given to her should not be correct. She would not lead a dull life, why should she? Having a sense of humour she often saw fun where others saw just the reverse. Anyhow she was determined to be in a gay mood at the working party and if it was possible to get any fun out of it, she would. She was not fond of her needle but that did not signify, and indeed could not be helped.

Rachel looked through her dresses and with a little chuckle chose one which, as she told Luke afterwards, would astonish the "natives." It was not exactly a dress for a working party, but she resolved that now she was to make her first appearance she should be dressed prettily for Luke's sake. So determined to forget the morning cooking lesson, she started off directly dinner was over, in a merry mood. Luke had had only time to sit down to a hurried meal before he was due at a clerical meeting, so she had not the pleasure of showing her pretty frock to her husband before leaving the house.

Arrived at Mrs. Stone's house, she was shown into the drawing-room which seemed full to overflowing of ladies, all elderly and all talking, till she made her appearance. Then the buzz ceased for a moment and Rachel felt conscious of about thirty pairs of eyes scrutinising her. But she was nothing daunted being quite used to meeting strangers and to being made much of by them. She was shown a seat near Mrs. Stone who at once took her under her wing, and Rachel congratulated herself on this fact, for her face was pleasant and smiling, and she looked as if humour was not left out of her composition.

Rachel felt at home at once and before long Mrs. Greville, glancing across the room, wondered what caused the quiet ripple of laughter that came from the corner where Rachel sat. She noticed that her daughter-in-law was looking exceedingly pretty and happy. There was no distressed frown on her brow which she had noticed in the morning; she looked the gayest of the gay. Mrs. Greville wished that she had put on a more suitable dress and a hat that did not look as if it had come out of Bond Street. She was quite a foreign element in the room and it rather worried Luke's mother to see how the ladies round her daughter-in-law laid down their work again and again to listen more easily to Rachel's conversation. Could it be possible that she heard Polly's name? Surely Rachel was not making fun of the girl she had secured for her. Besides there was nothing whatever to laugh at in Polly. She was a staid little body and a thoroughly good teachable girl. But yes; there it was again. No doubt Mrs. Stone who looked so thoroughly amused was drawing her out. It was really very awkward and tiresome. She only wished that Rachel was more staid and more what a clergyman's wife should be.

Mrs. Greville looked longingly at the clock, it was just upon four. She would propose to Rachel that she should not wait for tea as Luke might be wanting his. It would be quite easy to do, and natural.

Rachel rose delighted at Mrs. Greville's suggestion made in a low tone of voice. She had enjoyed herself and had talked freely about some of her difficulties in house keeping, quite unconscious of the fact, that she was being drawn out by some members of the working party with not altogether kind motives. She had addressed most of her conversation to Mrs. Stone, whom she liked, feeling instinctively that she was a woman to be trusted, but she gradually began to feel a little uneasy at the probing questions of some of the others; questions which she felt they had no right to ask; and which there was no necessity to answer; but she was so anxious to make friends with Luke's people and not to annoy them by showing her own annoyance that she was conscious that she was talking more than she ought. So when Mrs. Greville proposed to her to go home in case Luke was back from the clerical meeting, she rose with alacrity, and was pleased when Mrs. Stone said that she was so sorry that she had to leave as she had added greatly to the pleasure of the afternoon.

When the door closed behind her, an amused smile passed from one to the other of those who had been sitting near her.

"The Vicar has certainly given us a surprise," said one in a low voice, so that Mrs. Greville could not hear. "She has roused us all up this afternoon."

"A more unsuitable clergyman's wife I cannot imagine," said another.

"Her hat must have cost three pounds at least," remarked a third, "and as for her dress!"

"She was not a surprise to me," said a friend of Mrs. Greville's. "For I gathered from hints of the Vicar's mother that she was quite incapable. Not that she does not like her, and is thankful that she is devoted to her son, but she wishes he had chosen another kind of girl for his wife."

"Mrs. Greville," said Mrs. Stone, in a voice that all could hear, "I'm delighted with your daughter-in-law. She is so sunny and amusing. She will do us all good."

Mrs. Greville smiled with pleasure but shook her head a little.

"She is very young," she said, "only nineteen, and it will, I fear, take a long time before she settles down to undertake the responsibilities of being head of the parish."

"But," said Mrs. Stone, "surely there is no need to take that position yet. We have you and could not have anyone better. Let her have a little more time before being weighed down with the needs of a parish. She is full of fun and vitality, and should not have too much put upon her all at once. Let her take up the duties gradually; it is not as if she had been brought up to it."

Mrs. Greville sighed audibly.

Meanwhile Rachel hurried home. She had not known that there was a chance of her husband coming back to tea, and was delighted with the prospect. She felt happy, and a little elated, hoping that she had made a good impression on the working party. Mrs. Stone had been particularly nice to her, and so had one or two others. At the same time she could not forget the grave face of a lady who sat near enough to hear all the fun and nonsense she had been talking. This lady had not once looked up from her work, and had actually shaken her head over one or two of Rachel's remarks. The remembrance of her and the look of evident surprise on the faces of others rather weighed upon her spirits as she neared home. Had she talked too much? Had she been frivolous? She hoped not. She wanted to help Luke and not to hinder him, and she could not forget Mrs. Greville's words, about the necessity of the Vicar's wife setting an example to the parish.

Her face was a little grave as she opened the dining-room door, but the sight of her husband's smile of welcome as he looked up from the letter he was writing, cheered her.

"I did not stop to tea," he said, "as I have to write some important letters before the choir practice this evening, I know you won't mind me not talking."

Rachel ran upstairs to take off her hat and then busied herself in getting the tea. So he was going out again this evening! She was disappointed. However, she congratulated herself that she had him to tea.

"Well," he said, as he laid down his pen at Rachel's announcement that tea was ready. "How did you get on at the working party? I'm glad they have seen you."

"But they didn't like me," said Rachel laughing, "at least some of them did not."

"Nonsense. How could they help it?" He took her face between his hands, and looked lovingly into her eyes.

"They think I'm too young and frivolous, and moreover incapable, and not half worthy of their Vicar," answered Rachel. "I read it all in their faces, and I'm quite sure that with the exception of Mrs. Stone and one or two others I shocked them. But let me go and pour out your tea. You have a lot to do."

Luke seated himself at the table and began cutting the loaf of bread.

"What did you say to shock them?" he said.

"I enlarged upon Polly's peculiarities. I like Polly, she amuses me immensely, and I really feel that I could make quite a nice little maid of her, if only I knew how things ought to be done myself. Happily there are a few things I do know, and I take pains to inform Polly of them. But she is the queerest little creature I have ever seen."

Luke was not listening. He was looking at Rachel, thinking what a radiant wife God had given him; and a fear arose in his heart, lest marrying him might be the cause of her high spirits being quenched, and of life taking on a too sober hue. Sin abounded in his parish and he did not see how Rachel could learn of all the evil, and be as bright and happy as she now was.

"You must not let those ladies who looked gravely upon you this afternoon, count too much," he said. "Some of them have been at the work for years, and have got too solemn and severe."

Rachel laughed.

"Don't be afraid," she said. "I could not imagine myself not seeing the fun in things; my only fear is that I shall be too frivolous for them."

Luke did not smile; he was still wondering if he had done right in bringing Rachel into the midst of all the sadness of his world. She seemed made for happiness and flowers and the singing of birds. She had loved the country and the trees and the beauties of the world; and now he had brought her into a sordid town, and into a poky little house with the saddest of outlooks. He had never realised, as he did this afternoon, what he had done.

"Now what are you considering?" she said playfully, as his eyes still dwelt gravely on her face. "Are you disappointed in me too? Well, if so you will have to put up with me 'till death us do part.' Are you glad Luke?" She looked at him over the tea pot, leaning forward towards him, with the sweetest of smiles.

"It is just that; I am not sure that I am glad," he said slowly.

Rachel laughed again. She knew he did not mean what his words implied.

"Well, here I am, and you must make the best of me. But please don't look at me any more, but eat your tea or you won't get through your letters. I wish I could help you to write them."

"That unfortunately you could not do as they are private. However, there is something else you might do. Do you think you can come with me to the choir practice and play the organ? Crewse had to go home on business, and will not be back in time, so if you don't come I shall have to do my best. But bad is the best; besides if I am paying attention to the organ, I can't look at the boys. You do play the organ, don't you?"

"I should love to do it," said Rachel. Here was at least an opportunity of helping Luke. She had begun to wonder when the chance of doing so would come her way, as all the posts in the parish seemed to be filled up, and those that were not were appropriated by her mother-in-law.

"You must not expect a good choir," said Luke. "There are not many musical people, and what there are, are caught up naturally by the mother parish. However, we are doing what we can, and you won't anyhow have to suffer by listening to anthems. I have put down my foot at that. If anthems are sung I believe in them being sung perfectly, so that people may not be prevented worshipping God as they listen, by hearing discordant sounds and wrong notes. So you will be spared that."

Rachel did not think that she would mind even that, so long as Luke was in the church, but she did not say so.

The church was built of red brick, red both inside and out. It lacked beauty of architecture, and Rachel missed the wonderful feeling there is in the thought that for generations worship to God has ascended from the place. But on the other hand it was kept beautifully clean and was very airy and bright, and Luke was devoted to it.

Rachel seated at the organ sent up a prayer of thanksgiving, that she was allowed to help her husband, and hoped fervently that the choir master might often have to go away on business so that she could take his place. Moreover, besides the pleasure it gave her to help Luke, she loved playing the organ, and had been used to doing so in her little village church at home, and this evening she saw Luke in a new light. This was the first time she had seen him among his people, and it interested her much. Also she saw how very much reverence counted in his estimation. He evidently never forgot that he and his choir were in Church and in the presence of God, and Rachel noticed how this sense of God's Presence was communicated to the men and boys, and indeed to herself. As she played the organ she felt that she was not only serving Luke, but One much higher than Luke.

When the practice was over and the choir dispersed, he still remembered that they were in a sacred building and lowered his voice as he spoke to her, and took her round the church.

"I have it always open," he explained to her, "so that those who live in crowded rooms can have a quiet place to come and pray."

"And do they come?" asked Rachel.

"I have only once found anyone here," he said, "but I often remind them of the fact, that it is possible for them to pray in quiet. And I'm quite determined that the Church shall be kept as it should be. We Evangelicals, sometimes err in not looking after material things such as neat hassocks, and dusted benches. We think so much of the spiritual side of the work, that the material is neglected."

"Our little Church at home, for instance," said Rachel, "the door is kept shut all the week and so it always has a musty smell on Sunday. It is such a pity."

"I have heard people remark in discussing St. Mary's Church, that the way it is kept would put people off going there if they did not know what a splendid preacher Mr. Simpson is. As it is, the place is crowded. I don't suppose the Rector has the faintest idea of the state of his church. He is thinking altogether of more important matters, but it is a pity. They have not anything like so good a preacher at our Church," he added, laughing, "but they have a cleaner and more airy building and I intend that it should be kept so."

"Don't you think Mr. Crewse will be obliging and leave the organ to me?" said Rachel. "I should love to be your Organist. I play rather nicely, does he play as well?"

"Not nearly as well. That is to say he does not take pains with the expression as you do. His great aim seems to be to make the boys sing loud. However, he has his very good points and I fear I must not fill up his post," he added. "It would break his heart."

"That would be a bad beginning for me."

Rachel found it a little difficult to keep up her spirits as the days passed. Luke was so engrossed with Parish matters that she saw little of him; and when he was at home, his thoughts were apparently full of his work. He did not realise how little he talked of anything else, nor how long his silences were. His great desire to keep all sorrowful things from his wife prevented him sharing his worries with her, and instead of coming home after a meeting he would often turn in to 10, High Street, and discuss the difficulties with his mother, while Rachel tried to occupy herself in things over which she had to concentrate her attention so as not to worry over his long absences.

At times he would suddenly awake to the consciousness that Rachel was not looking quite as bright as usual and felt remorse at having taken her away from her home.

On these occasions he would try and manage to get a free day off and take her for a jaunt. But he felt it an effort and it put him back in his work. These free days, however, were days of bliss to his wife, till she recognised the fact that it was only when he was not engaged in his life work that they had communion with one another. She was of no help to him in the most important times of his life. This knowledge made her grow restless and unhappy.

At last she spoke to him of her longing to help him more. They had gone by train to some woods not far off and had lunch in a lovely spot they had discovered. The morning was bright and sunny, and as weather had a great effect on Rachel she was in a merry mood which communicated itself to her husband. Then, as after lunch they still sat on enjoying the rest and the smell of the damp earth, Rachel sighed.

"Isn't this heavenly?" she said. "I wish we lived in the country, don't you?"

"No, I don't," said Luke. "I should die of ennui! and I cannot imagine life without plenty of work. My work is my life."

"And I am kept outside," said Rachel. The moment the words were out of her mouth she regretted them.

Luke looked down at her in surprise.

"How do you mean?" he asked.

Rachel, her hands clasped round her knees, looked up into the branches of the tree above her, saying slowly, "I mean that there does not seem any possible way in which I can help you or share your life; for you say your work is your life. I am outside your work."

Luke did not answer. He was conscious that what she said was true. Had he not taken pains that her bright spirit might not be quenched by knowing all the sin that abounded in his parish? He could not bear the thought of his wife hearing the sad stories that she would inevitably come across if she worked in the parish. He felt convinced that the shock she would receive would be too much for her sensitive spirit. No, she was meant for happiness; why cloud it before the time? After a moment of troubled silence, he said:

"As for helping me, you can best do that dearest, by being happy. You cannot tell what it is to me when I come home to find you there; and to know that you have not been troubled by the sin that has weighed upon my own heart all day. The very fact of being with someone who is unconnected with it is a tremendous help."

Rachel was silent. It did not seem to cross Luke's mind that it was difficult to keep happy and bright so long as she had only the house and its cares to think about. She needed outside interests to fill her unoccupied time and thoughts.

"I suppose your mother shares your difficulties with you?" she said.

"Yes. My mother always has done so. She has a happy knack of letting troubles of that sort drop away from her like water off a duck's back. That is one of the great differences between you and her. She is not sensitive as you are, and she has worked so long at this kind of thing that she does not feel it as you would. My mother is just the one that I need in my work. I can discuss anything with her and I lean considerably on her judgment." He did not see the change of expression on his wife's face, nor that the sun had gone out of it, but he noticed her silence.

"You understand, don't you?" he said.

Rachel did not answer, but kept her eyes on the top branches of the tree above her. He did not know her eyes were full of tears. He thought he had explained the situation to her satisfaction, and supposed she knew him well enough to understand that it was his great love for her that was the cause of his decision not to worry her with his troubles.

And Rachel, sitting by his side on the soft moss, kept her eyes away, and wondered if all men were as ignorant of a woman's heart as Luke, or whether it was just because he lived so much up in the clouds that he had never studied human nature.

Luke flung himself back on the moss with his hands behind his head and looked in the same direction as his wife. The silence between them struck him as beautiful and restful, and he felt certain that Rachel was enjoying it to the full, as he was. Silence is the greatest proof of friendship, and it was a luxury to him.

Rachel on the other hand, felt she had rather too much of that luxury. As yet she had made no real friends. Mrs. Stone was the one that she liked best, but they were not on sufficiently intimate terms for her to feel she could run into her house should she be dull. So that with the exception of Polly and her mother-in-law she had no conversation except when callers came. And the callers were not always of the stamp of people with whom she could exchange thoughts. Besides, they often talked about people and things of which she knew nothing, as Luke was not communicative. She sometimes felt in an awkward position in consequence.

"What!" they would exclaim. "Did not the Vicar tell you?"

So now as Luke lay back enjoying the quiet and fully convinced that his wife, whom he loved as his own soul, was equally enjoying it, Rachel sat looking away from him feeling miserable and lonely, conscious that Luke had not found her the helpmeet he had expected her to be. She was feeling it all so much that she knew if the subject was again touched upon she would burst into tears, and cause her husband surprise and worry; so when she had successfully controlled her feelings she turned the conversation to the beauty of the trees. She felt it almost difficult to think of anything to talk about that would interest him, as he had just told her that his work was his life, and she was debarred from taking any part in it.

But Luke, quite unconscious of the sad thoughts of his wife, enthusiastically agreed in her admiration of the trees and began reciting a poem on the subject, thus giving Rachel time to try to get over her sore feelings; before the poem was finished she was able to turn and smile upon him.

"I never indulged in these holidays before I married," he said laughing, "consequently I revel in them with you beside me. You can't think Rachel what it is to come home and find you always there. It is a little heaven on earth. Don't say again that you are outside my life or don't help me. It just makes all the difference to me and to my work. Do you know that sometimes in the very midst of it I suddenly think of you and thank God for giving you to me."

Rachel flushed with happiness. If this really was so, and Luke was not one to flatter, perhaps her longing to be near him in the battle with evil and sin in the belief that she could help him, was a mistake. She was more of a help to him, apparently, in seeing to his house and welcoming him back from his work than if she was actually fighting, as it were, by his side.

Suddenly her thoughts were interrupted by Luke saying, as he had said on that moonlight night at Southwold, which seemed now so long ago:

"Sing Rachel."

Rachel hesitated. "I don't know what to sing," she said.

"Sing what you sang at Southwold, on the sea. What a perfect night that was, do you remember?"

Remember! Rachel could never forget it. How often had the thought of it saddened her. Somehow things had not been just as she had hoped and expected on that moonlight evening when she and Luke had been alone on the great wide sea. She had never had him quite so absolutely to herself since that day; ever since then she had had to share him with others. No, she could not sing those words just now. They seemed sacred to that wonderful time which they had spent in the pathway of the moon.

"Not that Luke," she remonstrated.

"Well sing something else," he said, not having noticed the slight tremor in her voice. "I want to hear your voice among the trees."

"I'll sing the two last verses of your favourite hymn," she said.

"Drop Thy still dews of quietness,

Till all our strivings cease;

Take from our souls the strain and stress

And let our ordered lives confess

The beauty of Thy peace.

Breathe through the heats of our desire

Thy coolness and Thy balm,

Let sense be dumb, let flesh retire,

Speak through the earthquake, wind and fire.

O still small voice of calm."

Luke did not move. He lay looking up at the green leaves above him. Then he said:

"How is it you always know exactly the right words to sing? My soul has been full of strain and stress lately. A great deal of sadness is going on among my people. I need to let the peace of God rule my heart, and to listen to 'the still small voice of calm,' and to remember that there is my wife at home praying for me."

Rachel forgot her own trials to think of his.

"I did not know you had been so worried," she said, her voice full of sympathy. "Have people been horrid?"

"No, not horrid to me; but the devil is playing havoc in the place, and it is a strain."

Rachel felt ashamed. Luke had been enduring the strain and stress of battle with the enemy, thinking altogether of his people, while she had been engrossed in her own little trials, caused by an insane jealousy of the one who was the only person who could advise and help him. How small she was! How poor and mean! How unlike the good Christian that Luke supposed her to be. She was filled with shame and scorn of herself.

Luke was beginning to feel acutely the great necessity of a study. When his mother had lived with him she had left the dining-room entirely for his use in the mornings, and had been careful not to interrupt him by going in and out. In fact, in those days they had kept no servant, and Mrs. Greville had been so busy in the house that she had not needed to use the room at all.

But since Luke had married and Polly had come as maid, things had been different. Rachel was constantly in the room, and though she took pains to be as quiet as possible, and sometimes sat so still working, that, had it not been that Luke had heard her enter, he would not have known she was there, he was more or less conscious of her presence, and this very consciousness was an interruption.

Luke at this time was not only busy with his parish and his sermons; he was grappling with the great enemy in his own soul.

The literature of the day was flooded with scepticism, and the truths he held most dear were questioned, not only by avowed unbelievers, but by those who held important positions in the Church; and for the sake, not only of his own soul but for those of his people, he had to face these questions and to answer them to his own perfect satisfaction.

He felt that the only way to fight the great enemy was by hard study and constant prayer. And both these duties were almost impossible under the present circumstances. He needed to be alone with God, and not to be subject to continual interruptions even from his wife. Moreover he felt that a study was necessary, so that people who needed spiritual advice or comfort might not be afraid of coming to see him.

Then he had suffered considerably from Rachel's efforts to keep the dining-room tidy. The papers that he left lying about his writing table had been often neatly arranged in heaps, and he had spent several minutes in sorting them. Yet he felt he could not blame the dear hands that had done it, for he happened to know that Polly was not allowed to touch his writing table; Rachel undertook its dusting and arrangement herself. Had he a study he could safely leave his papers about and make a rule that they should not be touched except by himself.

Yes, a study was absolutely necessary.

One morning its necessity was borne in upon him more than ever. He had some very important letters to write and in the midst of them, Polly came in to lay the cloth for dinner. Some of his papers he had put on the table and the laying of the cloth involved their removal. He was just in the midst of answering a very difficult question and felt he could not possibly be interrupted.

"Ask Mrs. Greville to put off dinner for half an hour," he said. Rachel ran in.

"Do you really want dinner put off Luke?" she asked. "It will, I fear, all be spoilt."

"I'm sorry, but it can't be helped. This letter has to go by the 3 o'clock post. Don't let Polly come in again till I tell you."

To Rachel, Luke's dinner was of more importance than any number of letters, but she saw he was a little worried and so left the room at once. Half an hour afterwards she heard the front door slam.

"Quick Polly," she said, "Mr. Greville has evidently gone to the post, lay the table as fast as you can."

But Luke must have gone further than the post. Ten minutes passed away and he had not returned.

"I do believe he has forgotten dinner," said Rachel, looking at Polly with a woe-begone face.

"It is a shame," said Polly, "and you've got such a nice one for him. It's just like the master; he don't think of himself a bit. He's thinking of them people."

And Luke, perfectly unconscious of the surprised distress he had left behind him, knowing that he was late for an engagement, hurried into a pastry cooks, bought a penny bun, and went off to his meeting, thinking to himself, "I must have a study somehow or other. It is impossible to do my work without it."

Should he suggest to Rachel to turn the little spare room into a study? No, that would prevent her having her sister to stay with her upon which, he knew, she had set her heart. He felt almost inclined to go to the extravagance of renting a room in the house where his mother lived. That was not a bad idea at all. He would talk it over with his mother.

When he returned home, to his surprise he found Rachel looking worried.

"Oh Luke," she said, as she glanced up from her work when he opened the door. "What have you been doing? Do you know that you have had no dinner and that Polly and I waited for ours till three o'clock, hoping that you would come. It is really too bad of you." Rachel was evidently ruffled.

"I've had lunch, so don't worry dear," he said, "I'm a bad boy I fear."

Rachel laughed.

"You are a very bad boy indeed," she said, "and don't a bit deserve to have a wife who has prepared a particularly nice dinner for you. But what have you had, and where did you have it?"

"I got a bun, and that supported me well all through the meeting for which I was nearly late."

"A bun! only a bun! Oh Luke, you really are impossible. Of course," she added as she rose, "you must have a proper meal now."

"No, have tea early and give me an egg. That's all I feel inclined for."

He made his way towards his writing table, then stopped short.

"Who has been moving my papers?" he asked.

Rachel started. She had never heard Luke speak so irritably before.

"I have been tidying up," she said, "I hope I have done no mischief. All the letters I have put in the top drawer. See, here they are," opening the drawer quickly, "and your larger papers and books I have laid together. They are quite all right. I was most careful of them."

Luke checked the expression of impatience that he was about to use, and only said:

"I'd rather that they had been left just as I put them. It delays me to have to hunt for letters."

"But the room had to look tidy," said Rachel distressed, "and I thought that if anyone came in to see me and happened to be shown into the dining-room you would not care for your letters to be strewn about. You remember you left in a hurry."

"So I did," he said. "I had forgotten. And you are quite right; the letters ought not to be left about where any one can see them. However," he added, sitting down at his writing table and beginning to look through the top drawer, "it all makes my way plainer. It is positively necessary to have a study where need not be disturbed."

"Why not have dinner in the drawing-room on the days you are at home in the mornings," said Rachel, anxious to help him.

"Oh no, I could not think of that. What I feel I must do is to get a room somewhere; in the house, for instance, where my mother lodges. I must manage it somehow."

Rachel standing by his side while he sorted his papers was quite silent. It was all that she could do not to cry out, "Oh Luke, why are you so blind; why do you hurt me so?" As it was, she stood perfectly still and silent.

The days on which Luke wrote his sermons were red letter days. She loved to sit near him and work; and she had had the impression that the sense of her presence helped him. She had told him once that she sat praying for him as he wrote, and he had kissed her as his thanks. Evidently she had been mistaken; he would prefer to be alone. And why, oh why should he choose to find a room in his mother's house? It would be the beginning of seeing far less of him than ever. Of course his mother would persuade him to stay to dinner with her if his next duty was near her rooms; and it would be only human nature for her to discuss his wife with him and to hint that she was incapable. But she put this thought away from her at once. She was so certain that Luke would not discuss her with anyone, even with his mother.

Her perfect silence made Luke look round, and the expression on her face perplexed him. He covered the hand that lay on the back of his chair with his own, saying remorsefully:

"I'm afraid, dearest, I was a little sharp just now. You must forgive me. You were perfectly right to tidy away my papers; but you will understand that it would be easier for me if I had a room where I could leave them about and find them easily. Besides," he said, "I want more time for private prayer and a place where I cannot be interrupted. My work is suffering for want of this."

"I see," said Rachel. She tried to smile, but failed. "I so love being with you when you write your sermons," she added.

"And I have loved to have you. But the work must come first; and I am convinced that for every reason it will be better to have a room quite to myself." He turned round again to finish sorting his papers.

Rachel came to a sudden determination.

"You won't engage that room till you have thought a little longer about it," she pleaded.

"I shall engage it to-morrow if possible," he answered with decision.

And Rachel said in her heart, "You shall not engage it to-morrow."

Then she went out to find Polly.

"Polly," she said in a soft voice, "do you think your father could come round this evening and bring a man with him. I want to give Mr. Greville a surprise and make the spare room into his study. He will be out at a meeting till nine o'clock. Could you just run round do you think? I will get the tea."

The little spare room had been arranged with the hope that her sister Sybil would soon be able to come and pay them a visit. It was dreadfully disappointing that now she would not be able to take her in. She would have to get a room out for her which would not be nearly so nice. But anything would be better than for Luke to rent a room in his mother's house. She could not endure that. If he did that she would see less and less of him, and she did not think it could be good for a husband to get used to being a long time away from his wife. In fact she simply could not bear it. Sybil's little room at the top of the stairs must be turned into a study; and all the time Rachel was preparing the tea she was planning where to place the furniture and his books. The very idea of giving him such a surprise had the effect of sending away all melancholy thoughts, and Luke, who had been as startled to see such a look of melancholy on his wife's face as she had been to hear his somewhat irritable tone of voice, was relieved to see her as bright as usual, and determined never to allow any irritability to find its way into his heart towards her again.

At ten o'clock that evening Rachel sat by the open window in the drawing-room listening for her husband's footstep. She was very tired, as though Polly's father had, with the help of another man, taken up Luke's writing table and book shelves, etc., and moved other furniture into the spare room. Rachel and Polly had between them moved the books and had arranged them as near as possible in the same order in the shelves, as Luke had arranged them himself in the dining-room. She had taken out of the dining-room two of his favourite pictures and had hung them over his table; and she had placed a large armchair by the window so that he could read in comfort.

And now she sat wondering if Luke would be pleased, or if the very careful moving of his papers would again vex him. Her heart beat as she heard him open the door and she ran to meet him. She drew him into the drawing-room, saying:

"I have such a surprise for you."

But Luke hardly seemed to hear her. His face was radiant, and Rachel saw at once that something had happened to make him very happy and to engage all his thoughts.

"I have such good news to tell you," he said, as he sank rather wearily into a chair.

"What is it?" asked Rachel. After the excitement of the evening his preoccupation rather damped her spirits. That it was not the time to spring her surprise upon him she felt at once, so she took up her needle work and sat down. She could not but notice the expression on his face. She could not think of any other word by which to describe it to herself, but radiant, and a longing that he did not live quite so up in the clouds, as she would have expressed it, took possession of her; he had evidently not heard her remark as she had met him at the door; or if he had heard it, it was to him of such infinitely minor importance than the news he was about to communicate to her, that he had ignored it.

As he was silent before answering her question Rachel said again, and he didn't notice the faint tone of impatience in the voice.

"What is your wonderful news? Do tell me."

"That's just it," he said looking joyfully at her. "It is wonderful. A man who has been the ringleader of a lot of harm in the parish, has to-night made the great decision; in other words, he has been converted."

"Oh Luke, how beautiful," said Rachel.

Rachel knew what this news meant to her husband. For a moment the study was forgotten.

"He has only twice been to the class;" continued Luke, "and the first time he made himself troublesome by arguing with me. But he came again to my surprise, and to-night, well, it was wonderful. It only shows what God can do. It was just a word of Scripture that struck him and would not let him rest. He was quite broken down."

Rachel's work had dropped on to her knee and she sat looking at her husband. His face reminded her of the parable of the lost sheep and of the joy in the Presence of God over one sinner that repented. Even in the days of their perfect courtship, even on that wonderful moonlight night on the sea at Southwold, she had never seen such joy on his face. His love for his Lord, and His work, exceeded, evidently, every other love and interest. Rachel looking into her own heart and remembering how comparatively little communion she experienced with her Lord, compared to Luke, felt inclined to weep. She had been wholly taken up with her husband and his home and with the determination of keeping him all to herself. She had not given much time to prayer; and even in those moments in which she had knelt down night and morning she found her thoughts wandering away to Luke, and revolving round him. Her conscience accused her loudly.

"I will bring in your cocoa," she said rising, "Polly has gone to bed."

It was after drinking his cocoa, that she told him again that she had a surprise waiting for him.

They ran upstairs together, his arm round her. He was in such buoyant spirits. Then Rachel opened the study door.

For the first moment he was silent from astonishment. Then he took her face between his hands and kissed her.

"But I don't approve of the surprise at all," he said, laughing. "What about Sybil?"

"Sybil will have a room out. I would a hundred times rather that you should write your sermons in your own home and near me than that you should get a room elsewhere. Do you like it?"

"Like it? I should think so." Then his face became grave. "But where are my letters and papers?" he asked anxiously.

"Perfectly safe. I have put an elastic band round the letters and they are in exactly the same order as you left them, and so are your other papers which you will find in the long top drawer. Then I have told Polly that she is never to come into the study, but that I will see to it. So you can leave everything about, dear; or lock the room up when you are out."

Luke busy among his papers looked up with a smile.

"Are you sure you would not mind me doing that? I can't tell you what a relief it would be to me to know that nothing has been moved."

"I will dust it early in the morning before your letters come," said Rachel, "and then you will be sure that you can leave everything about and it won't be interfered with."

His smile of pleasure was enough reward for Rachel.

The Bishop was in his garden, surrounded by the Clergy of his diocese and their wives. He was a grey-haired man, upright and spare of build. His face was full of kindness and love as he went among his guests, entering into their difficulties and encouraging them in their work.

It was his annual garden party, and he looked forward to it almost as much as did his clergy. Being a widower, had it not been for his work he would have felt the Palace lonely. It was an old and hoary building, and lay in the shadow of the cathedral; but the greater part of the garden was full of sunshine, and wherever the Bishop was, there was brightness and the atmosphere of love and fellowship.

He now stood glancing around as if looking for someone; then he caught sight of Rachel who was making her way swiftly towards him, her face alight with love and eagerness.

The child is happy, he thought gladly, and stretched out both his hands in welcome.

"I was looking for you," he said, "and was hoping that you and your good husband were not going to play me false. Where is he?"

"He's coming by the next train, in half an hour's time, but I was so impatient to see you that I told him I could not wait. Some parishioner has been taken ill and he had to go and see him. But I simply had to come."

"Now," said the Bishop, "I want to know all about your dear mother, and about your new life. We will go towards the nut walk where we shall not be interrupted. I also want to show you the Palace. I promised to do that in the old days I remember."

"It's perfectly delightful to talk to anyone who remembers those old days," said Rachel, with a slight catch in her voice, "and specially with you of all people. How father loved you."

"He was my best friend," said the Bishop, "and the world for me is the poorer for his absence. But tell me about your new life. Are you getting used to it?"

A slight cloud crossed Rachel's face which was not unnoticed by the Bishop.

"It's just a little difficult," she answered. "Luke's parishioners are quite different from any people I have met; some of them are nice, and they adore Luke. But oh they are so funny! They take offence at such small things. I don't think they like me much. You see I was labelled as young and incompetent before they saw me. But after all it does not much matter, as I have Luke. Perhaps if it were not for a few worries I should be almost too happy."

"You have a good husband in Greville."

Rachel looked up into the Bishop's face. Her look was enough to convince him of her happiness.

"He's much too good for me," she said, "I'm not half worthy of him, and of course his people can't help seeing that, specially his mother."

"She does not live with you, does she?"

"No. She turned out for me, but she lives very near."

The Bishop detected a shade of bitterness in the little laugh that escaped her lips.

"Is it difficult?" he asked kindly.

"I think you had better not ask me," said Rachel. Then unable to restrain her feelings, she added, "She just spoils everything, and I am so afraid of Luke finding it out; he is so devoted to her."

The Bishop was silent.

"The worst of it is," said Rachel, after a slight pause, "I can't talk it over with Luke, so there is a secret always between us. Don't you think it was horrid of her to tell people how incapable she thinks me? The result is that I can't help Luke in his work; people don't believe in me."

"How do you know this?"

"Someone let it out by mistake when she called," said Rachel. "There are always, I suppose, people like that in a place who talk more than they mean to. This person is a regular gossip, and I learnt more about the people in half an hour from her than I should have learnt in a year from Luke. Luke never tells me anything. I wish he would."

"No, I don't think you should wish that. A man who does not talk over his people is a man to be trusted with the secrets of their souls. That is just the one disadvantage in my eyes of a man being married. It is difficult for some wives to tolerate their husbands not telling them what should be kept sacred. For every other reason I am a great advocate of married clergy. A wife may be of the very greatest help to a man. But in order to be so she must be a woman of high ideals, and one who understands what is due to his position. But my dear child, why did not you try to turn the conversation of this parishioner? Take my advice and don't listen to criticisms of yourself."

"I am not sure that I have high ideals," said Rachel with a little laugh, "but I'm afraid I do like being appreciated. I am sure the people as a whole don't like me, and I can't think why."

The Bishop laughed.

"I expect you are mistaken about that," he said, "It's very easy to get fancies of that sort into one's head."