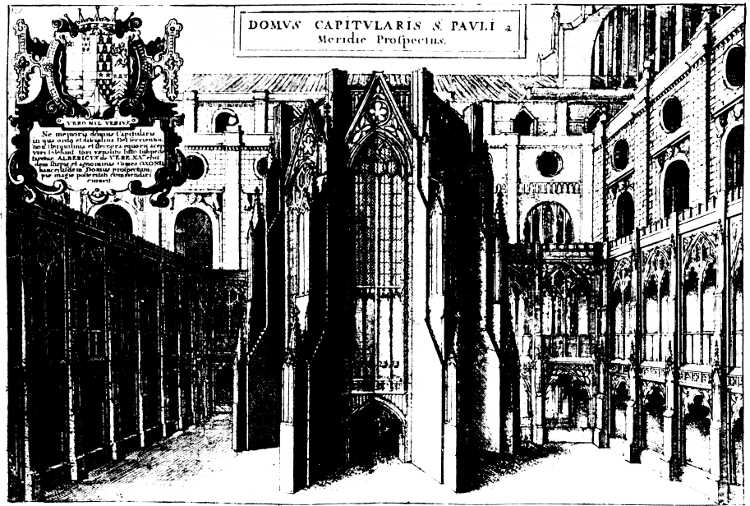

FROM THE ENGRAVING BY WENCESLAUS HOLLAR IN DUGDALE’S

St. Paul’s 1658

THE ELIZABETHAN STAGE

VOL. II

Oxford University Press

London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen

New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town

Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai

Humphrey Milford Publisher to the University

FROM THE ENGRAVING BY WENCESLAUS HOLLAR IN DUGDALE’S

St. Paul’s 1658

OXFORD: AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M.CMXXIII

[v]

Printed in England

| BOOK III. THE COMPANIES | ||||

| PAGE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XII. | Introduction. The Boy Companies | 1 | ||

| A. | Introduction | 3 | ||

| B. | The Boy Companies— | |||

| i. | Children of Paul’s | 8 | ||

| ii. | Children of the Chapel and Queen’s Revels | 23 | ||

| iii. | Children of Windsor | 61 | ||

| iv. | Children of the King’s Revels | 64 | ||

| v. | Children of Bristol | 68 | ||

| vi. | Westminster School | 69 | ||

| vii. | Eton College | 73 | ||

| viii. | Merchant Taylors School | 75 | ||

| ix. | The Earl of Leicester’s Boys | 76 | ||

| x. | The Earl of Oxford’s Boys | 76 | ||

| xi. | Mr. Stanley’s Boys | 76 | ||

| XIII. | The Adult Companies | 77 | ||

| i. | The Court Interluders | 77 | ||

| ii. | The Earl of Leicester’s Men | 85 | ||

| iii. | Lord Rich’s Men | 91 | ||

| iv. | Lord Abergavenny’s Men | 92 | ||

| v. | The Earl of Sussex’s Men | 92 | ||

| vi. | Sir Robert Lane’s Men | 96 | ||

| vii. | The Earl of Lincoln’s (Lord Clinton’s) Men | 96 | ||

| viii. | The Earl of Warwick’s Men | 97 | ||

| ix. | The Earl of Oxford’s Men | 99 | ||

| x. | The Earl of Essex’s Men | 102 | ||

| xi. | Lord Vaux’s Men | 103 | ||

| xii. | Lord Berkeley’s Men | 103 | ||

| xiii. | Queen Elizabeth’s Men | 104 | ||

| xiv. | The Earl of Arundel’s Men | 116 | ||

| xv. | The Earl of Hertford’s Men | 116 | ||

| xvi. | Mr. Evelyn’s Men | 117 | ||

| xvii. | The Earl of Derby’s (Lord Strange’s) Men | 118 | ||

| xviii. | The Earl of Pembroke’s Men[vi] | 128 | ||

| xix. | The Lord Admiral’s (Lord Howard’s, Earl of Nottingham’s), Prince Henry’s, and Elector Palatine’s Men | 134 | ||

| xx. | The Lord Chamberlain’s (Lord Hunsdon’s) and King’s Men | 192 | ||

| xxi. | The Earl of Worcester’s and Queen Anne’s Men | 220 | ||

| xxii. | The Duke of Lennox’s Men | 241 | ||

| xxiii. | The Duke of York’s (Prince Charles’s) Men | 241 | ||

| xxiv. | The Lady Elizabeth’s Men | 246 | ||

| XIV. | International Companies | 261 | ||

| i. | Italian Players in England | 261 | ||

| ii. | English Players in Scotland | 265 | ||

| iii. | English Players on the Continent | 270 | ||

| XV. | Actors | 295 | ||

| BOOK IV. THE PLAY-HOUSES | ||||

| XVI. | Introduction. The Public Theatres | 353 | ||

| A. | Introduction | 355 | ||

| B. | The Public Theatres— | |||

| i. | The Red Lion Inn | 379 | ||

| ii. | The Bull Inn | 380 | ||

| iii. | The Bell Inn | 381 | ||

| iv. | The Bel Savage Inn | 382 | ||

| v. | The Cross Keys Inn | 383 | ||

| vi. | The Theatre | 383 | ||

| vii. | The Curtain | 400 | ||

| viii. | Newington Butts | 404 | ||

| ix. | The Rose | 405 | ||

| x. | The Swan | 411 | ||

| xi. | The Globe | 414 | ||

| xii. | The Fortune | 435 | ||

| xiii. | The Boar’s Head | 443 | ||

| xiv. | The Red Bull | 445 | ||

| xv. | The Hope | 448 | ||

| xvi. | Porter’s Hall | 472 | ||

| XVII. | The Private Theatres | 475 | ||

| i. | The Blackfriars | 475 | ||

| ii. | The Whitefriars | 515 | ||

| XVIII. | The Structure and Conduct of Theatres | 518 | ||

[vii]

| Domus Capitularis Sti Pauli a Meridie Prospectus. By Wenceslaus Hollar. From Sir William Dugdale, History of St. Paul’s Cathedral (1658) | Frontispiece |

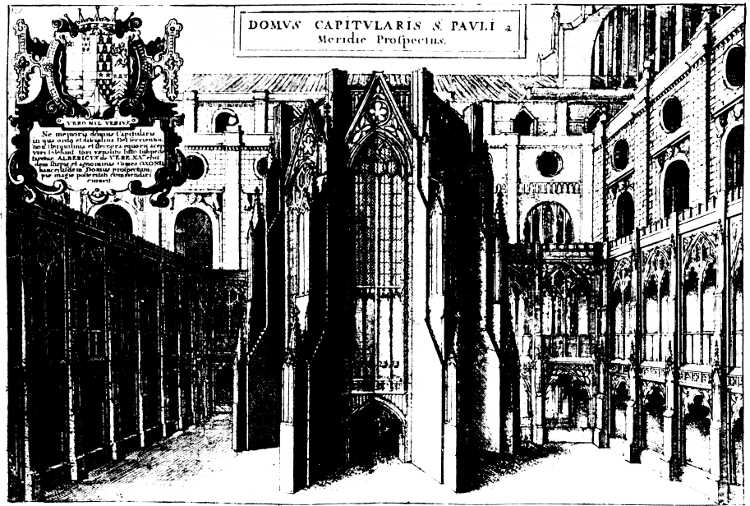

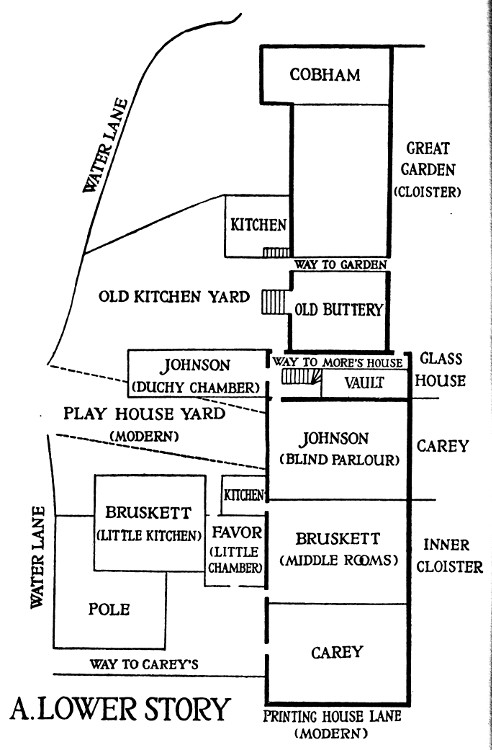

| Diagrams of the Blackfriars Theatres | p. 504 |

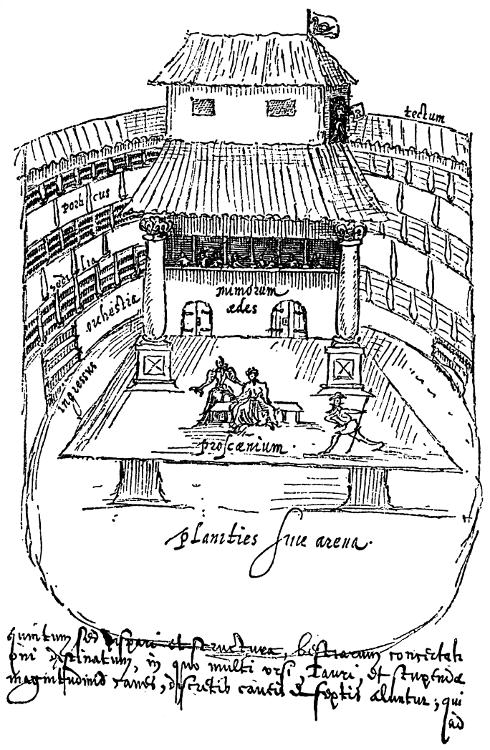

| Interior of the Swan Theatre. From the drawing after Johannes de Witt in Arend van Buchell’s commonplace book | p. 521 |

I have found it convenient, especially in Appendix A, to use the symbol < following a date, to indicate an uncertain date not earlier than that named, and the symbol > followed by a date, to indicate an uncertain date not later than that named. Thus 1903 < > 23 would indicate the composition date of any part of this book. I have sometimes placed the date of a play in italics, where it was desirable to indicate the date of production rather than publication.

[1]

[Bibliographical Note.—The first systematic investigation into the history of the companies was that of F. G. Fleay, which, after tentative sketches in his Shakespeare Manual (1876) and Life and Work of Shakespeare (1886), took shape in his Chronicle History of the Stage (1890). Little is added by the compilations of A. Albrecht, Das Englische Kindertheater (1883), H. Maas, Die Kindertruppen (1901) and Äussere Geschichte der Englischen Theatertruppen (1907), and J. A. Nairn, Boy-Actors under the Tudors and Stewarts (Trans. of Royal Soc. of Lit. xxxii). W. W. Greg, Henslowe’s Diary (1904–8), made a careful study of all the companies which had relations with Philip Henslowe, and modified or corrected many of Fleay’s results. An account of the chief London companies is in A. H. Thorndike, Shakespeare’s Theater (1916), and utilizes some new material collected in recent years. W. Creizenach, Schauspiele der Englischen Komödianten (1889), and E. Herz, Englische Schauspieler und Englisches Schauspiel (1903), have summarized the records of the travels of English actors in Germany. C. W. Wallace, besides his special work on the Chapel, has published the records of several theatrical lawsuits in Advance Sheets from Shakespeare, the Globe, and Blackfriars (1909), in Nebraska University Studies, ix (1909), 287; x (1910), 261; xiii (1913), 1, and in The Swan Theatre and the Earl of Pembroke’s Servants (1911, Englische Studien, xliii. 340); the present writer has completed the information drawn from the Chamber Accounts in P. Cunningham’s Extracts from the Accounts of the Revels at Court (1842) by articles in M. L. R. ii (1906), 1; iv (1909), 153 (cf. App. B); and a number of documents, new and old, including the texts of all the patents issued to companies, have been carefully edited in vol. i of the Collections of the Malone Society (1907–11). Finally, J. T. Murray, English Dramatic Companies (1910), has collected the published notices of performances in the provinces, added others from the municipal archives of Barnstaple, Bristol, Coventry, Dover, Exeter, Gloucester, Marlborough, Norwich, Plymouth, Shrewsbury, Southampton, Winchester, and York, and on the basis of these constructed valuable accounts of all the London and provincial companies between 1558 and 1642. Most of the present chapter was written before Murray’s book appeared, but it has been carefully revised with the aid of his new material. I have not thought it necessary to refer to my original provincial sources, where they are included in his convenient Appendix G, but in using his book it should be borne in mind that he has made a good many omissions in carrying data from this Appendix to the tables of provincial visits, which he gives for each company. For a few places I have had the advantage of sources not drawn upon by Murray, and these should be treated as the references for any facts as regards such places not discoverable in Murray’s Appendix.[2] They are:—for Belvoir and other houses of the Earls of Rutland, Rutland MSS. (Hist. MSS.), iv. 260; for the house of Richard Bertie and his wife the Duchess of Suffolk at Grimsthorpe, Ancaster MSS. (Hist. MSS.), 459; for Wollaton, the house of Francis Willoughby, Middleton MSS. (Hist. MSS.), 446; for Maldon and Saffron Walden in Essex, A. Clark’s extracts in 10 Notes and Queries, vii. 181, 342, 422; viii. 43; xii. 41; for Newcastle-on-Tyne, G. B. Richardson, Reprints of Rare Tracts, vol. iii, and 10 N. Q. xii. 222; for Reading, Hist. MSS. xi. 177; for Oxford, F. S. Boas in Fortnightly Review (Aug. 1913; Aug. 1918; May 1920); for Stratford, J. O. Halliwell, Stratford-upon-Avon in the Time of the Shakespeares, illustrated by Extracts from the Council-Books (1864); for Weymouth, H. J. Moule, Weymouth and Melcombe Regis Documents (1883), 136; for Dunwich, Various Collections (Hist. MSS.), vii. 82; for Aldeburgh, Suffolk, C. C. Stopes, William Hunnis, 314. References for a few other scattered items are in the foot-notes. The warning should be given that the dates assigned to some of the provincial performances are approximate, and may be in error within a year or so either way. For this there are more reasons than one. The zealous antiquaries who have made extracts from local records have not realized that precise dates might be of value, and have often named a year without indicating whether it represents the calendar year (Circumcision style) or the calendar year (Annunciation style) in which a performance fell, or the calendar year in which a regnal, mayoral, or accounting year, in which the performance fell, began or ended. When they are clearly dealing with accounting years, they do not always indicate whether these ended at Michaelmas or at some other date. They sometimes give only the year of a performance, when they might have given, precisely or approximately, the month and day of the month as well. But it is fair to add that the accounts of City Chamberlains and similar officers, from which the notices of plays are generally derived, are not always so kept as to render precise dating feasible. Some accountants specify the days, others the weeks to which their entries relate; others put their entries in chronological order and date some of them, so that it is possible to fix the dates of the rest within limits; others again render accounts analysed under heads, grouping all payments to players perhaps under a head of ‘Gifts and Rewards’, and in such cases you cannot be sure that the companies are even entered in the order of their visits, and if months and days are not specified, cannot learn more than the year to which a visit belongs. Where, for whatever reason, I can only assign a performance to its accounting year, I generally give it under the calendar year in which the account ends. This, in the case of a London company and of a Michaelmas year (much the commonest year for municipal accounts), is pretty safe, as the touring season was roughly July to September. Some accounting years (Coventry, Marlborough, Stratford-on-Avon) end later still, but if, as at Bath, the year ends about Midsummer, it is often quite a toss-up to which of two years an entry belongs. In the case of Leicester performances before 1603, I have combined the indications of Michaelmas years in M. Bateson, Leicester Records, vol. iii, with those of calendar years in W. Kelly, Notices Illustrative of the Drama (1865), 185, and distinguished between performances before and after Michaelmas. I hope Kelly has not misled me, and that he found evidence in the entries for his dating. After 1603 he is the only source. I do not think that the amount of error which has crept into the following chapter from the various causes described is likely to be at all considerable. I have been as careful as possible and most of Murray’s own extracting is excellently done. I should, however, add that the Ipswich dates, as given both here and by Murray, ii. 287.[3] from Hist. MSS. ix. i, 248, are unreliable, because some of the rolls from which they are taken contain membranes properly belonging to those for other years; cf. my notes on Leicester’s (pp. 89, 91), Queen’s (p. 106), Warwick’s (p. 99), Derby’s (p. 120), King’s (p. 209).]

The present chapter contains detailed chronicles—too often, I fear, lapsing into arid annals of performances at Court or in the provinces—of all the companies traceable in London during any year between 1558 and 1616. The household and other establishments to which the companies were attached are taken as the basis of classification. This principle is open to criticism. Certainly it has not always the advantage of presenting economic units. It is improbable that there was any continuity as regards membership between the bodies of actors successively appearing, often after long intervals, under the names of Sussex or Hunsdon or Derby. On the other hand, particular associations of actors can sometimes be discerned as holding together under a change of patrons. Thus between 1571 and 1583 Laurence and John Dutton seem to have led a single company, which earned the nickname of the Chameleons, first in the service of Sir Robert Lane and then, turn by turn, in that of the Earls of Lincoln, Warwick, and Oxford. The real successors, again, of the Derby’s men of 1593 are less the Derby’s men of 1595–1618 than the Hunsdon’s men of 1594–1603, who in course of time became the King’s men without any breach of their unity as a trading association. Nevertheless, an arrangement under patrons is a practicable one, since companies nearly always appear under the names of their patrons in official documents, while an arrangement under trading associations is not. Actors are a restless folk, and the history of the Admiral’s men, or the Queen’s Revels, or the Lady Elizabeth’s men, will show how constantly their business organizations were disturbed by the coming and going of individuals, and by the breaking and reconstruction of the agreements on which they were based. It is but rarely that we have any clue to these intricacies; and I have therefore followed the households as the best available guides, indicating breaches of continuity and affiliations, where these appear to exist, and adopting as far as possible an order which, without pretence of being scientific, will bring each household under consideration roughly at the point at which its servants become of the greatest significance to the general history of the stage. The method may perhaps be described as that of a λαμπαδηφορία.

[4]

A study of the succession of the companies gives rise to a few general considerations. During the earlier years of Elizabeth’s reign the drama is under the domination of the boy companies. This may be in part due to the long-standing humanistic tradition of the Renaissance, although the lead is in fact taken not so much by schoolboys in the stricter sense, as by the trained musical establishments of the royal chapels and still more that of the St. Paul’s choir under Sebastian Westcott. More important points perhaps are, that the Gentlemen of the Chapel, who had been prominent under Henry VIII, had ceased to perform, that the royal Interluders had been allowed to decay, and that the other professional companies had not yet found a permanent economic basis in London, while their literary accomplishment was still upon a popular rather than a courtly level. Whatever the cause or causes, the fact is undeniable. Out of seventy-eight rewards for Court performances between 1558 and 1576, twenty-one went to the Paul’s boys, fifteen to the royal chapels, and ten to schoolboys, making a total of forty-six, as against only thirty-two paid to adult companies. And if the first half of this period only be taken, the disproportion is still greater, for by 1567 the Paul’s boys had received eleven rewards, other boys two, and the adult companies six. A complete reversal of this position coincides rather markedly with the building of the first permanent theatres in 1576. Between 1576 and 1583 the adult companies had thirty-nine rewards and the boys only seventeen. There is also a rapid growth in the number of companies. Before 1576 the Earl of Leicester’s men and the Duttons were alone conspicuous. After 1576 the entertainment of a London company seems to become a regular practice with those great officers the Lord Chamberlain and the Lord Admiral, as well as with special favourites of the Queen, such as the Earl of Leicester himself or the Earl of Oxford. Stockwood in 1578 speaks of ‘eighte ordinarie places’ in the City as occupied by the players. A Privy Council order of the same year limits the right to perform to six companies selected to take part in the Court festivities at Christmas, namely Leicester’s men, Warwick’s, Sussex’s, Essex’s, and the Children of the Chapel and St. Paul’s. Gabriel Harvey, writing to Edmund Spenser of the publication of his virelays in the following summer, says:

‘Ye have preiudished my good name for ever in thrustinge me thus on the stage to make tryall of my extemporall faculty, and to play Wylsons or Tarletons parte. I suppose thou wilt go nighe hande shortelye to sende my lorde of Lycesters or my lorde of Warwickes,[5] Vawsis, or my lord Ritches players, or sum other freshe starteupp comedanties unto me for sum newe devised interlude, or sum maltconceivid comedye fitt for the Theater, or sum other paintid stage whereat thou and thy lively copesmates in London maye lawghe ther mouthes and bellyes full for pence or twoepence apeece.’[1]

Doubtless many of this mushroom brood of ‘freshe starteupp comedanties’ never succeeded in making good their permanent footing in the metropolis. Lord Vaux’s men, whom Harvey mentions, were never fortunate enough to be summoned to Court; and the same may be said of Lord Arundel’s men, Lord Berkeley’s, and Lord Abergavenny’s. Such men, after their cast for fortune, had to drift away into the provinces, and pad the hoof on the hard roads once more.

The next septennial period, 1583–90, witnessed the extinction, for a decade or so, of the boy companies, in spite of the new impulse given to the latter by the activity as a playwright of John Lyly. Of forty-five Court payments made during these years, thirty apparently went to men and only fifteen to boys. This ultimate success of the professional organizations may largely have been due to their employment of such university wits as Marlowe, Peele, Greene, Lodge, and Nashe in the writing of plays, with which Lyly could be challenged on his own ground before the Court, while a sufficient supply of chronicle histories and other popular stuff could still be kept on the boards to tickle the ears of the groundlings. The undisputed pre-eminence lay during this period with the Queen’s men, who made within it no less than twenty-one appearances at Court. This company enjoyed the prestige of the royal livery, transferred to it from the now defunct Interluders, which had a ready effect in the unloosing of municipal pockets. And at its foundation in 1583 it incorporated, in addition to Tarlton, whose origin is unknown, the leading members of the pre-existing companies: Wilson and Laneham from Leicester’s, Adams from Sussex’s, and John Dutton from Oxford’s. The former fellows of these lucky ones were naturally hardly able to maintain their standing. In January 1587 Leicester’s, Oxford’s, and the Admiral’s were still setting up their bills side by side with those of the Queen’s.[2] But the first two are not heard of at Court again, and even the Admiral’s were hardly able to make a show except by coalition with other companies. Thus we find the Admiral’s combining with Hunsdon’s in 1585, and with Strange’s perhaps from 1589 onwards, and it became the destiny of this last alliance,[6] under the leadership of Edward Alleyn, to dispossess the Queen’s men, after the death of Tarlton in 1588, from their pride of place. The fall of the Queen’s men was sudden. In 1590–1 they gave four Court plays to two by their rivals; in 1591–2 they gave one, and their rivals six. In their turn they appear to have been reduced to forming a coalition with Lord Sussex’s men.

The plague-years of 1592–4 brought disaster, chaos, and change into the theatrical world. Only the briefest London seasons were possible. The necessities of travelling led to further combinations and recombinations of groups, one of which may have given rise to the ephemeral existence of Lord Pembroke’s men. And, by the time the public health was restored, the Queen’s had reconciled themselves to a provincial existence, and continued until 1603 to make their harvest of the royal name, as their predecessors in title had done, without returning to London at all. The combination of which Alleyn had been the centre broke up, and its component elements reconstituted themselves as the two great companies of the Chamberlain’s and the Admiral’s men. Between these there was a vigorous rivalry, which sometimes showed itself in lawsuits, sometimes in the more legitimate form of competing plays on similar themes. Thus a popular sentiment offended by the Chamberlain’s men in 1 Henry IV was at once appealed to by the Admiral’s with Sir John Oldcastle. And when the Admiral’s scored a success by their representation of forest life in Robin Hood, the Chamberlain’s were quickly ready to counter with As You Like It. I think the Chamberlain’s secured the better position of the two. They had their Burbadge to pit against the reputation of Alleyn; they had their honey-tongued Shakespeare; and they had a business organization which gave them a greater stability of membership than any company in the hands of Henslowe was likely to secure. If one may once more use the statistics of Court performances as a criterion, they are found to have appeared thirty-two times and their rivals only twenty times from 1594 to 1603. Between them the Chamberlain’s and the Admiral’s enjoyed for some years a practical monopoly of the London stage, which received an official recognition by the action of the Privy Council in 1597. But this state of things did not long continue. Ambitious companies, such as Pembroke’s, disregarded the directions of the Council. Derby’s men, Worcester’s, Hertford’s, one by one obtained at least a temporary footing at Court, and in 1602 the influence of the Earl of Oxford was strong enough to bring about the admission to a permanent home in London[7] of a third company made up of his own and Worcester’s servants. Even more dangerous, perhaps, to the monopoly was the revival of the boy companies, Paul’s in 1599 and the Chapel in 1600. The imps not only took by their novelty in the eyes of a younger generation of play-goers. They began a warfare of satire, in which they ‘berattled the common stages’ with a vigour and dexterity that betray the malice of the poets against the players which had been a motive in their rehabilitation.[3]

No material change took place at the coming of James. The three adult companies, the Chamberlain’s, the Admiral’s, Worcester’s, passed respectively under the patronage of James, Prince Henry, and Queen Anne.[4] On the death of Prince Henry in 1612 his place was taken by the Elector Palatine. The Children of the Chapel also received the patronage of Queen Anne, as Children of the Queen’s Revels. The competition for popular favour continued severe. Dekker refers to it in 1608 and the preacher Crashaw in 1610.[5] It is to be noticed, however, that Dekker speaks only of ‘a deadly war’ between ‘three houses’, presumably regarding the boy companies as negligible. And in fact these companies were on the wane. By 1609 the Queen’s Revels, though still in existence, had suffered from the wearing off of novelty, from the tendency of boys to grow older, from the plague-seasons of 1603–4 and 1608–9, which they were less well equipped than the better financed adults to withstand, from the indiscretions and quarrels of their managers, and from the loss of the Blackfriars, of which the King’s men had secured possession.[6] The Paul’s boys had been bought off by the payment of a ‘dead rent’ or blackmail to the Master. A third company, the King’s Revels, had been started, but had failed to establish itself.[7] The three houses were not, indeed, left[8] with an undisputed field. Advantage was taken of the predilection of the younger members of the royal family for the drama, and patents were obtained, in 1610 for a Duke of York’s company, and in 1611 for a Lady Elizabeth’s company. These also had but a frail life. In 1613 the Lady Elizabeth’s and the Queen’s Revels coalesced under the dangerous wardenship of Henslowe. In 1615 the Duke of York’s, now Prince Charles’s, men joined the combination. And finally in 1616 the Prince’s men were left alone to make up the tale of four London companies, and the Lady Elizabeth’s and the Queen’s Revels disappeared into the provinces. The list of men summoned before the Privy Council in March 1615 to account for playing in Lent contains the names of the leaders of the four companies, the King’s, the Queen’s, the Palsgrave’s, and the Prince’s. The King’s played at the Globe and Blackfriars, the Queen’s at the Red Bull, whence they moved in 1617 to the Cockpit, the Palsgrave’s at the Fortune, and the Prince’s at the Hope. The supremacy of the King’s men during 1603–16 was undisputed. Of two hundred and ninety-nine plays rewarded at Court for that period, they gave one hundred and seventy-seven, the Prince’s men forty-seven, the Queen’s men twenty-eight, the Duke of York’s men twenty, the Lady Elizabeth’s men nine, the Queen’s Revels boys fifteen, and the Paul’s boys three. Their plays, moreover, were those usually selected for performance before James himself. It is possible, however, that the Red Bull and the Fortune were better able to hold their own against the Globe when it came to attracting a popular audience.

| i. | Children of Paul’s. |

| ii. | Children of the Chapel and Queen’s Revels. |

| iii. | Children of Windsor. |

| iv. | Children of the King’s Revels. |

| v. | Children of Bristol. |

| vi. | Westminster School. |

| vii. | Eton College. |

| viii. | Merchant Taylors School. |

| ix. | Earl of Leicester’s Boys. |

| x. | Earl of Oxford’s Boys. |

| xi. | Mr. Stanley’s Boys. |

High Masters of Grammar School:—William Lily (1509–22); John Ritwise (1522–32); Richard Jones (1532–49); Thomas Freeman[9] (1549–59); John Cook (1559–73); William Malim (1573–81); John Harrison (1581–96); Richard Mulcaster (1596–1608).

Masters of Choir School:—? Thomas Hikeman (c. 1521); John Redford (c. 1540);? Thomas Mulliner (?); Sebastian Westcott (> 1557–1582); Thomas Giles (1584–1590 <); Edward Pearce (> 1600–1606 <).

[Bibliographical Note.—The documents bearing upon the early history of the two cathedral schools, often confused, are printed and discussed by A. F. Leach in St. Paul’s School before Colet (Archaeologia, lxii. 1. 191) and in Journal of Education (1909), 503. M. F. J. McDonnell, A History of St. Paul’s School (1909), carries on the narrative of the grammar school. The official chroniclers of the cathedral, perhaps owing to the loss of archives in the Great Fire, have given no connected account of the choir school; with the material available on the dramatic side they appear to be unfamiliar. Valuable contributions are W. H. G. Flood, Master Sebastian, in Musical Antiquary, iii. 149; iv. 187; and H. N. Hillebrand, Sebastian Westcote, Dramatist and Master of the Children of Paul’s (1915, J. G. P. xiv. 568). Little is added to the papers on Plays Acted by the Children of Paul’s and Music in St. Paul’s Cathedral in W. S. Simpson, Gleanings from Old St. Paul’s (1889), 101, 155, by J. S. Bumpus, The Organists and Composers of St. Paul’s Cathedral (1891), and W. M. Sinclair, Memorials of St. Paul’s Cathedral (1909).]

Mr. Leach has succeeded in tracing the grammar school, as part of the establishment of St. Paul’s Cathedral, to the beginning of the twelfth century. It was then located in the south-east corner of the churchyard, near the bell-tower, and here it remained to 1512, when it was rebuilt, endowed, and reorganized on humanist lines by Dean Colet, and thereafter to 1876, when it was transferred to Horsham in Sussex. Originally the master was one of the canons; but by the beginning of the thirteenth century this officer had taken on the name of chancellor, and the general supervision of the actual schoolmaster, a vicar choral, was only one of his functions. Distinct from the grammar school was the choir school, for which the responsible dignitary was not the chancellor, but the precentor, in whose hands the appointment of a master of the song school rested.[8] There was, however, a third branch of the cathedral organization also concerned with the training of boys. The almonry or hospital, maintained by the chapter for the relief of the poor, seems to have been established at the end of the twelfth century,[10] and statutes of about the same date make it the duty of a canon residentiary to assist in the maintenance of its pueri elemosinarii, and prescribe the special services to be rendered them at their great annual ceremony of the Boy Bishop on Innocents’ Day.[9] In the thirteenth century the supervision of these boys was in the hands of another subordinate official, appointed by the chapter and known as the almoner. The number of the boys was then eight; it was afterwards increased, apparently in 1358, to ten.[10] The almoner is required to provide for their literary and moral education, and their liturgical duties are defined as consisting of standing in pairs at the corners of the choir and carrying candles.[11] A later version of the statutes provides for their musical education, and it is clear that these pueri elemosinarii were in fact identical with or formed the nucleus of the boys of the song school.[12] During the sixteenth century the posts of almoner and master of the song school, although technically distinct, were in practice held together, and the holder was ordinarily a member of the supplementary cathedral establishment known as the College of Minor Canons.[13] To this college had been appropriated the parish church of St. Gregory, on the south side of St. Paul’s, just west of the Chapter or Convocation House, and here the song school was already[11] housed by the twelfth century.[14] The college had also a common hall on the north of the cathedral, near the Pardon churchyard; and hard by was the almonry in Paternoster Row.[15] The statutes left the almoner the option of either giving the boys their literary education himself, or sending them elsewhere. It naturally proved convenient to send them to the grammar school, and the almoners claimed that they had a right to admission without fees.[16] On the other side we find the grammar school boys directed by Colet to attend the Boy Bishop ceremony and make their offerings.[17] Evidently there was much give and take between song school and grammar school.

As early as 1378 the scholars of Paul’s are said to have prepared a play of the History of the Old Testament for public representation at Christmas.[18] Whether they took a share in the other miracles recorded in mediaeval London, it is impossible to say. A century and a half later the boys of the grammar school, during the mastership of John Ritwise, are found contributing interludes, in the humanist fashion, to the entertainment of the Court. On 10 November 1527 they gave an anti-Lutheran play in Latin and French before the King and the ambassadors of Francis I, and in the following year the Phormio before Wolsey, who also saw them, if Anthony Wood can be trusted, in a Dido written by Ritwise[12] himself.[19] There is no evidence that Ritwise’s successors followed his example by bringing their pupils to Court; and the next performances by Paul’s boys, which can be definitely traced, began a quarter of a century later, and were under the control of Sebastian Westcott, master of the song school, and were therefore presumably given by boys of that school. Westcott in 1545 was a Yeoman of the Chamber at Court.[20] He was ‘scolemaister of Powles’ by New Year’s Day 1557, when he presented a manuscript book of ditties to Queen Mary.[21] Five years earlier, he had brought children to Hatfield, to give a play before the Princess Elizabeth; and the chances are that these were the Paul’s boys.[22] With him came one Heywood, who may fairly be identified with John Heywood the dramatist; and this enables us, more conjecturally, to reduce a little further the gap in the dramatic history of the Paul’s choir, for some years before, in March 1538, Heywood had already received a reward for playing an interlude with ‘his children’ before the Lady Mary.[23] There is nothing beyond this phrase to suggest that Heywood had a company of his own, and it is not probable that he was ever himself master of the choir school.[24] But he may very[13] well have supplied them with plays, both in Westcott’s time and also in that of his predecessor John Redford. Several of Heywood’s verses are preserved in a manuscript, which also contains Redford’s Wyt and Science and fragments of other interludes, not improbably intended for performance by the boys under his charge.[25] A play ‘of childerne sett owte by Mr. Haywood’ at Court during the spring of 1553 may also belong to the Paul’s boys.[26] Certain performances ascribed to them at Hatfield, during the Princess Elizabeth’s residence there in her sister’s reign, have of late fallen under suspicion of being apocryphal.[27]

From the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign Westcott’s theatrical enterprise stands out clearly enough. On 7 August 1559 the Queen was entertained by the Earl of Arundel at Nonsuch with ‘a play of the chylderyn of Powlles and ther Master Se[bastian], Master Phelypes, and Master Haywod’.[28] If ‘Master Phelypes’ was the John Philip or Phillips who wrote Patient Grissell (c. 1566), this play may also belong[14] to the Paul’s repertory. Heywood could not adapt himself again to a Protestant England, and soon left the country. Sebastian Westcott was more fortunate. In 1560 he was appointed as Head of the College of Minor Canons or Sub-dean.[29] Shortly afterwards, being unable to accept the religious settlement, he was sentenced to deprivation of his offices, which included that of organist, but escaped through the personal influence of Elizabeth, in spite of some searchings of the heart of Bishop Grindal as to his suitability to be an instructor of youth.[30] In fact he succeeded in remaining songmaster of Paul’s for the next twenty-three years, and during that period brought his boys to Court no less than twenty-seven times, furnishing a far larger share of the royal Christmas entertainment, especially during the first decade of the reign, than any other single company. The chronicle of his plays must now be given. There was one at each of the Christmases of 1560–1 and 1561–2, one between 6 January and 9 March 1562, and one at the Christmas of 1562–3.[31] During the next winter the plague stopped London plays. At the Christmas of 1564–5 there were two by the Paul’s boys, of which the second fell on 2 January, and at that of 1565–6 three, two at Court and one at the Lady Cecilia’s lodging in the Savoy. There were two again at each of the Christmases of 1566–7 and 1567–8, and one on 1 January 1569. During the winter of 1569–70 the company was, exceptionally, absent from Court. They reappeared on 28 December 1570, and again at Shrovetide (25–7 February) 1571. On 28 December 1571 they gave the ‘tragedy’ of Iphigenia, which Professor Wallace identifies with the comedy called The Bugbears, but which might, for the matter of that, be Lady Lumley’s translation from the Greek of Euripides. At the Christmas of 1572–3 they played before 7 January.[15] On 27 December 1573 they gave Alcmaeon. They played on 2 February 1575, and a misfortune which befell them in the same year is recorded in a letter of 3 December from the Privy Council, which sets out that ‘one of Sebastianes boyes, being one of his principall plaiers, is lately stolen and conveyed from him’, and instructs no less personages than the Master of the Rolls and Dr. Wilson, one of the Masters of Requests, to examine the persons whom he suspected and proceed according to law with them.[32] Five days later the Court of Aldermen drew up a protest against Westcott’s continued Romish tendencies.[33] The next Court performance by the boys was on 6 January 1576. On 1 January 1577 they gave Error, and on 19 February Titus and Gisippus. They played on 29 December 1577, and one wonders whether it was anything amiss with that performance which led to an entry in the Acts of the Privy Council for the same day that ‘Sebastian was committid to the Marshalsea’.[34] Whether this was so or not, the Paul’s boys were included in the list of companies authorized to practise publicly in the City for the following Christmas. On 1 January 1579 they gave The Marriage of Mind and Measure, on 3 January 1580 Scipio Africanus, and on 6 January 1581 Pompey. A play on 26 December 1581 is anonymous, but may possibly be the Cupid and Psyche mentioned as ‘plaid at Paules’ in Gosson’s Playes Confuted of 1582.[35]

In the course of 1582 Sebastian Westcott died, and this event led to an important development in the dramatic activities of the boys.[36] Hitherto their performances, when not[16] at Court, had been in their own quarters ‘at Paules’, although the notice of 1578, as well as Gosson’s reference, suggests that the public were not altogether excluded from their rehearsals. Probably they used their singing school, which may have been still, as in the twelfth century, the church of St. Gregory itself.[37] This privacy, even if something of a convention, had perhaps enabled them to utilize the services of the grammar school when they had occasion to make a display of erudition.[38] After Westcott’s death, however, they appear to have followed the example of the Chapel, who had already[17] in 1576 taken a step in the direction of professionalism, by transferring their performances to Farrant’s newly opened theatre at the Blackfriars. Here, if the rather difficult evidence can be trusted, the Paul’s boys appear to have joined them, and to have formed part of a composite company, to which Lord Oxford’s boys also contributed, and which produced the Campaspe and Sapho and Phao of the earl’s follower John Lyly. Lyly took these plays to Court on 1 January and 3 March 1584, and Henry Evans, who was also associated with the enterprise, took a play called Agamemnon and Ulysses on 27 December. On all three occasions the official patron of the company was the Earl of Oxford. In Agamemnon and Ulysses it must be doubtful whether the Paul’s boys had any share, for in the spring of 1584 the Blackfriars theatre ceased to be available, and the combination probably broke up.[39] This, however, was far from being the end of Lyly’s connexion with the boys, for the title-pages of no less than five of his later plays acknowledge them as the presenters. They had, indeed, a four years’ period of renewed activity at Court, under the mastership of Thomas Giles, who, being already almoner, became Master of the Song School on 22 May 1584, and in the following year received a royal commission to ‘take up’ boys for the choir, analogous to that ordinarily granted to masters of the Chapel Children.[40] There is no specific mention of plays in[18] the document, but its whole basis is in the service which the boys may be called upon to do the Queen in music and singing. Under Giles the company appeared at Court nine times during four winter seasons; on 26 February 1587, on 1 January and 2 February 1588, on 27 December 1588, 1 January and 12 January 1589, and on 28 December 1589, 1 January and 6 January 1590. The title-pages of Lyly’s Endymion, Galathea, and Midas assign the representation of these plays at Court to a 2 February, a 1 January, and a 6 January respectively. Endymion must therefore belong to 1588 and Midas to 1590; for Galathea the most probable of the three years is 1588. Mother Bombie and Love’s Metamorphosis can be less precisely dated, but doubtless belong to the period 1587–90. At some time or other, and probably before 1590, the Paul’s boys performed a play of Meleager, of which an abstract only, without author’s name, is preserved. It is not, I think, to be supposed that Lyly, although he happened to be a grandson of the first High Master of Colet’s school, had any official connexion either with that establishment or with the choir school. It is true that Gabriel Harvey says of him in 1589, ‘He hath not played the Vicemaster of Poules and the Foolemaster of the Theatre for naughtes’.[41] But this is merely Harvey’s jesting on the old dramatic sense of the term ‘vice’, and the probabilities are that Lyly’s relation as dramatist to Giles as responsible manager of the company was much that which had formerly existed between John Heywood and Sebastian Westcott. Nevertheless, it was this connexion which ultimately brought the Paul’s plays to a standstill. Lyly was one of the literary men employed about 1589 to answer the Martin Marprelate pamphleteers in their own vein, and to this end he availed himself of the Paul’s stage, apparently with the result that, when it suited the government to disavow its instruments, that stage was incontinently suppressed.[42] The reason may[19] be conjectural, but the fact is undoubted. The Paul’s boys disappear from the Court records after 1590. In 1591 the printer of Endymion writes in his preface that ‘Since the Plaies in Paules were dissolved, there are certaine Commedies come to my handes by chaunce’, and the prolongation of this dissolution is witnessed to in 1596 by Thomas Nashe, who in his chaff of Gabriel Harvey’s anticipated practice in the Arches says, ‘Then we neede neuer wish the Playes at Powles vp againe, but if we were wearie with walking, and loth to goe too farre to seeke sport, into the Arches we might step, and heare him plead; which would bee a merrier Comedie than euer was old Mother Bomby’.[43]

A last theatrical period opened for the boys with the appointment about 1600 of a new master. This was one Edward Pearce or Piers, who had become a Gentleman of the Chapel on 16 March 1589, and by 15 August 1600, when his successor was sworn in, had ‘yealded up his place for the Mastership of the children of Poules’.[44] I am tempted to believe that in reviving the plays Pearce had the encouragement of Richard Mulcaster, who had become High Master of the grammar school in 1596, and during his earlier mastership of Merchant Taylors had on several occasions brought his boys to Court. Pearce is first found in the Treasurer of the Chamber’s Accounts as payee for a performance on 1 January 1601, but several of the extant plays produced during this section of the company’s career are of earlier date, and one of them, Marston’s I Antonio and Mellida, can hardly be later than 1599. A stage direction of this play apparently records the names of two of the performers as Cole and Norwood.[45] The Paul’s boys, therefore, were[20] ‘up again’ before their rivals of the Chapel, who cannot be shown to have begun in the Blackfriars under Henry Evans until 1600.[46] This being so, they were probably also responsible for Marston’s revision in 1599 of Histriomastix, which by giving offence to Ben Jonson, led him to satire Marston’s style in Every Man Out of His Humour, and so introduced the ‘war of the theatres’.[47] Before the end of 1600 they had probably added to their repertory Chapman’s Bussy d’Ambois, and certainly The Maid’s Metamorphosis, The Wisdom of Dr. Dodipoll, and Jack Drum’s Entertainment, all three of which were entered on the Stationers’ Register, and the first two printed, during that year. Jack Drum’s Entertainment followed in 1601 and contains the following interesting passage of autobiography:[48]

The criticism, being a self-criticism, must not be taken too seriously. So far as published plays are concerned, Histriomastix is the only one to which it applies. In Marston, Chapman, and Middleton the company had enlisted vigorous young playwrights, who were probably not sorry to be free from the yoke of the professional actors, and appear to have followed the exceptional policy of printing some at least of their new plays as soon as they were produced.

On 11 March 1601, two months after the boys made their first bow at Court, the Lord Mayor was ordered by the Privy Council to suppress plays ‘at Powles’ during Lent. It is to be inferred that they were, as of old, acting in their singing school. Confirmation is provided by a curious note appended by William Percy to his manuscript volume of[21] plays, presumably in sending them to be considered with a view to production by the boys. The plays bear dates in 1601–3, but it can hardly be taken for granted that they were in fact produced by the Paul’s or any other company. The note runs:

A note to the Master of Children of Powles.

Memorandum, that if any of the fine and formost of these Pastorals and Comoedyes conteyned in this volume shall but overeach in length (the children not to begin before foure, after prayers, and the gates of Powles shutting at six) the tyme of supper, that then in tyme and place convenient, you do let passe some of the songs, and make the consort the shorter; for I suppose these plaies be somewhat too long for that place. Howsoever, on your own experience, and at your best direction, be it. Farewell to you all.[49]

Both parts of Marston’s Antonio and Mellida were entered on the Stationers’ Register in the autumn of 1601 and printed in 1602. The second part may have been on the stage during 1601, and in the same year the boys probably produced John Marston’s What You Will, and certainly played ‘privately’, as the Chamberlain’s men did ‘publicly’, Satiromastix in which Dekker, with a hand from Marston, brought his swashing blow against the redoubtable Jonson. This also was registered in 1601 and printed in 1602. There is no sign of the boys at Court in the winter of 1601–2. In the course of 1602 their play of Blurt Master Constable, by Middleton, was registered and printed. They were at Court on 1 January 1603, for the last time before Elizabeth, and on 20 February 1604, for the first time before James. Either the choir school or the grammar school boys took part in the pageant speeches at the coronation triumph on 15 March 1604.[50] To the year 1604 probably belongs Westward Ho! which introduced to the company, in collaboration with Dekker, a new writer, John Webster. Northward Ho! by the same authors, followed in 1605. The company was not at Court for the winter of 1604–5, but during that of 1605–6 they gave two plays before the Princes Henry and Charles. For these the payee was not Pearce, but Edward Kirkham, who is described in the Treasurer of the Chamber’s account as ‘one of the Mres of the Childeren of Pawles’. Kirkham, who was Yeoman of the Revels, had until recently been a manager of the Children of the Revels at the Blackfriars. It may[22] have been the disgrace brought upon these by Eastward Ho! in the course of 1605 that led him to transfer his activities elsewhere.[51] With him he seems to have brought Marston’s The Fawn, probably written in 1604 and ascribed in the first of the two editions of 1606 to the Queen’s Revels alone, in the second to them ‘and since at Poules’. The charms of partnership with Kirkham were not, however, sufficient to induce Pearce to continue his enterprise. The last traceable appearance of the Paul’s boys was on 30 July 1606, when they gave The Abuses before James and King Christian of Denmark.[52] Probably the plays were discontinued not long afterwards. This would account for the large number of play-books belonging to the company which reached the hands of the publishers in 1607 and 1608. The earlier policy of giving plays to the press immediately after production does not seem to have endured beyond 1602. Those now printed, in addition to Bussy D’Ambois, What You Will, Westward Ho! and Northward Ho! already mentioned, included Middleton’s Michaelmas Term, The Phoenix, A Mad World, my Masters, and A Trick to Catch the Old One, together with The Puritan, very likely also by Middleton, and The Woman Hater, the first work of Francis Beaumont. The Puritan can be dated, from a chronological allusion, in 1606. The title-pages of The Woman Hater, A Mad World, my Masters, and A Trick to Catch the Old One specify them to have been ‘lately’ acted. It is apparent from the second quarto of A Trick to Catch the Old One that the Children of the Blackfriars took it over and presented it at Court on 1 January 1609. This was probably part of a bargain as to which we have another record. Pearce may have had at the back of his mind a notion of reopening his theatre some day. But it is given in evidence in the lawsuit of Keysar v. Burbadge in 1610 that, while it was still closed, he was approached on behalf of the other ‘private’ houses in London, those of the Blackfriars and the Whitefriars, and offered a ‘dead rent’ of £20 a year, ‘that there might be a cessation of playeinge and playes to be acted in the said howse neere St. Paules Church’.[53] This must have been in the winter of 1608–9, just as the[23] Revels company was migrating from the Blackfriars to the Whitefriars. The agent was Philip Rosseter who, with Robert Keysar, was financially interested in the Revels company. When the King’s men began to occupy the Blackfriars in the autumn of 1609, they took on responsibility for half the dead rent, but whether the arrangement survived the lawsuit of 1610 is unknown.

The Children of the Chapel (1501–1603).

Masters of the Children: William Newark (1493–1509), William Cornish (1509–23), William Crane (1523–45), Richard Bower (1545–61), Richard Edwardes (1561–6), William Hunnis (1566–97), Richard Farrant (acting, 1577–80), Nathaniel Giles (1597–1634).

The Children of the Queen’s Revels (1603–5).

The Children of the Revels (1605–6).

Masters: Henry Evans, Edward Kirkham, and others.

The Children of the Blackfriars (1606–9).

The Children of the Whitefriars (1609–10).

Masters: Robert Keysar and others.

The Children of the Queen’s Revels (1610–16).

Masters: Philip Rosseter and others.

[Bibliographical Note.—Official records of the Chapel are to be found in E. F. Rimbault, The Old Cheque Book of the Chapel Royal (1872, Camden Soc.). Most of the material for the sixteenth-century part of the present section was collected before the publication of C. W. Wallace, The Evolution of the English Drama up to Shakespeare (1912, cited as Wallace, i), which has, however, been valuable for purposes of revision. J. M. Manly, The Children of the Chapel Royal and their Masters (1910, C. H. vi. 279), W. H. Flood, Queen Mary’s Chapel Royal (E. H. R. xxxiii. 83), H. M. Hildebrand, The Early History of the Chapel Royal (1920, M. P. xviii. 233), are useful contributions. The chief published sources for the seventeenth century are three lawsuits discovered by J. Greenstreet and printed in full by F. G. Fleay, A Chronicle History of the London Stage (1890), 127, 210, 223. These are (a) Clifton v. Robinson and Others (Star Chamber, 1601), (b) Evans v. Kirkham (Chancery, May–June 1612), cited as E. v. K., with Fleay’s pages, and (c) Kirkham v. Painton and Others (Chancery, July–Nov. 1612), cited as K. v. P. Not much beyond dubious hypothesis is added by C. W. Wallace, The Children of the Chapel at Blackfriars (1908, cited as Wallace, ii). But Professor Wallace published an additional suit of importance, (d) Keysar v. Burbadge and Others (Court of Requests, Feb.–June 1610), in Nebraska University Studies (1910), x. 336, cited as K. v. B. This is apparently one of twelve suits other than Greenstreet’s, which he claims (ii. 36) to have found, with other material, which may alter the story. In the meantime, I see no reason to depart from the main outlines sketched in my article on Court Performances under James the First (1909, M. L. R. iv. 153).]

[24]

The Chapel was an ancient part of the establishment of the Household, traceable far back into the twelfth century.[54] Up to the end of the fourteenth, we hear only of chaplains and clerks. These were respectively priests and laymen, and the principal chaplain came to bear the title of Dean.[55] Children of the Chapel first appear under Henry IV, who appointed a chaplain to act as Master of Grammar for them in 1401.[56] In 1420 comes the first of a series of royal commissions authorizing the impressment of boys for the Chapel service, and in 1444 the first appointment of a Master of the Children, John Plummer, by patent.[57] It is probably to the known tastes of Henry VI that the high level of musical accomplishment, which had been reached by the singers of the Chapel during the next reign was due.[58] The status and duties of the Chapel are set out with full detail in the Liber Niger about 1478, at which date the establishment consisted of a Dean, six Chaplains, twenty Clerks, two Yeomen or Epistolers, and eight Children. These were instructed by a Master of Song, chosen by the Dean from ‘the seyd felyshipp of Chapell’, and a Master of Grammar, whose services were also available for the royal Henchmen.[59] There is no further record of the Master of Grammar; but with this exception the establishment continued to exist on much the same footing, apart from[25] some increase of numbers, up to the seventeenth century.[60] Although subject to some general supervision from the Lord Chamberlain and to that extent part of the Chamber, it was largely a self-contained organization under its own Dean. Elizabeth, however, left the post of Dean vacant, and the responsibility of the Lord Chamberlain then became more direct.[61] It probably did not follow, at any rate in its full numbers, a progress, but moved with the Court to the larger ‘standing houses’, except possibly to Windsor where there was a separate musical establishment in St. George’s Chapel.[62] It does not seem, at any rate in Tudor times, to have had any relation to the collegiate chapel of St. Stephen in the old palace of Westminster.[63] The number of Children varied between eight and ten up to 1526, when it was finally fixed by Henry VIII at twelve.[64] The chaplains and clerks were collectively known in the sixteenth century[26] as the Gentlemen of the Chapel, and the most important of them, next to one who acted as subdean, was the Master of the Children, who trained them in music and, as time went on, also formed them into a dramatic company. The Master generally held office under a patent during pleasure, and was entitled in addition to his fee of 7½d. a day or £91 8s. 1½d. a year as Gentleman and his share in the general ‘rewards’ of the Chapel, to a special Exchequer annuity of 40 marks (£26 13s. 4d.), raised in 1526 to £40, ‘pro exhibicione puerorum’, which is further defined in 1510 as ‘pro exhibicione vesturarum et lectorum’ and in 1523 as ‘pro sustencione et diettes’.[65] To this, moreover, several other payments came to be added in the course of Henry VIII’s reign. Originally the Chapel dined and supped in the royal hall; but this proved inconvenient, and a money allowance from the Cofferer of the Household was substituted, which was fixed in 1544 at 1s. a day for each Gentleman and 2s. a week for each Child.[66] The allowance for the Children was afterwards raised to 6d. a day.[67] Long before this, however, the Masters had succeeded in obtaining an exceptional allowance of 8d. a week for the breakfast of each Child, which was reckoned as making £16 a year and paid them in monthly instalments of 26s. 8d. by the Treasurer of the Chamber. The costs of the Masters in their journeys for the impressment of Children were also recouped by the Treasurer of the Chamber. And from him they also received rewards of 20s. when Audivi vocem was sung on All Saints’ Day, £6 13s. 4d. for the Children’s feast of St. Nicholas on 6 December, and 40s. when Gloria in Excelsis was sung on Christmas and St. John’s Days. These were, of course, over and above any special rewards received for dramatic performances.[68] In the provision of vesturae the Masters were helped by the issue from the Great Wardrobe of black and tawny camlet gowns, yellow satin coats, and Milan bonnets, which presumably constituted[27] the festal and penitential arrays of the choir.[69] The boys themselves do not appear to have received any wages but, when their voices had broken, the King made provision for them at the University or otherwise, and until this could be done, the Treasurer of the Chamber sometimes paid allowances to the Master or some other Gentleman for their maintenance and instruction.[70]

The earlier Masters were John Plummer (1444–55), Henry Abyngdon (1455–78), Gilbert Banaster (1478–83?), probably John Melyonek (1483–5), Lawrence Squier (1486–93), and William Newark (1493–1509).[71] Some of these have left[28] a musical or literary reputation, and Banaster is said to have written an interlude in 1482.[72] But until the end of this period only occasional traces of dramatic performances by the Chapel can be discerned. An alleged play by the Gentlemen at the Christmas of 1485 cannot be verified.[73] The first recorded performance, therefore, is one of the disguisings at the wedding of Prince Arthur and Katharine of Spain in 1501, in which two of the children were concealed in mermaids ‘singing right sweetly and with quaint hermony’.[74]

Towards the end of Henry VII’s reign begins a short series of plays given at the rate of one or two a year by the Gentlemen, which lasted through 1506–12.[75] Thereafter there is no other play by the Gentlemen as such upon record until the Christmas of 1553, when they performed a morality of which[29] the principal character was Genus Humanum.[76] This had been originally planned for the coronation on the previous 1 October, and as a warrant then issued states that a coronation play had customarily been given ‘by the gentlemen of the chappell of our progenitoures’, it may perhaps be inferred that Edward VI’s coronation play of ‘the story of Orpheus’ on 22 February 1547 was also by the Gentlemen.[77] In the meantime the regular series of Chapel plays at Court had been broken after 1512, and when it was taken up again in 1517 it was not by the Gentlemen, but by the Children.[78] This is, of course, characteristic of the Renaissance.[79] But an immediate cause is probably to be found in the personality of William Cornish, a talented and energetic Master of the Children, who succeeded William Newark in the autumn of 1509, and held office until his death in 1523.[80] Cornish appears to have come of a musical family.[81] He took part[30] in a play given by the Gentlemen of the Chapel shortly before his appointment as Master. And although it was some years before he organized the Children into a definite company, he was the ruling spirit and chief organizer of the elaborate disguisings which glorified the youthful court of Henry VIII from the Shrovetide of 1511 to the visit of the Emperor Charles V in 1522, and hold an important place in the story, elsewhere dealt with, of the Court mask.[82] In these revels both the Gentlemen and the Children of the Chapel, as well as the King and his lords and ladies took a part, and they were often designed so as to frame an interlude, which would call for the services of skilled performers.[83]

In view of Cornish’s importance in the history of the stage at Court, it is matter for regret that none of his dramatic writing has been preserved, for it is impossible to attach any value to the fantastic attributions of Professor Wallace, who credits him not only with the anonymous Calisto and Meliboea, Of Gentleness and Nobility, The Pardoner and the Frere, and Johan Johan, but also with The Four Elements and The Four P. P., for the authorship of which by John Rastell and John Heywood respectively there is good contemporary evidence.[84][31] Cornish was succeeded as Master of the Children by William Crane (1523–45) and Crane by Richard Bower, whose patent was successively renewed by Edward VI, presumably by Mary, and finally by Elizabeth on 30 April 1559.[85] His service was almost certainly continuous, and it is therefore rather puzzling to be told that a commission to take up singing children for the Chapel, similar to that of John Melyonek in 1484, was issued in February 1550 to Philip van Wilder, a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber.[86] Neither the full text nor a reference to the source for the warrant is given, and I suspect the explanation to be that it was not for the Chapel at all. Philip van Wilder was a lutenist, one of a family of musicians of whom others were in the royal service, and he may not improbably have had a commission to recruit a body of young minstrels with whom other notices suggest that he may have been connected.[87] Bower himself had a commission for the Chapel on 6 June 1552.[88] Although the Children continued to give performances at Court both under[32] Crane and under Bower, it may be doubted whether they were quite so prominent as they had been in Cornish’s time. Certainly they had to contend with the competition of the Paul’s boys. Crane himself is not known to have been a dramatist. It has been suggested that Bower’s authorship is indicated by the initials R. B. on the title-page of Apius and Virginia (1575), but, in view of the date of the publication, this must be regarded as very doubtful. The chief Marian producer of plays was Nicholas Udall, but it remains uncertain whether he wrote for the Chapel Children. Professor Wallace has no justification whatever for his confident assertions that John Heywood ‘not only could but did’ write plays for the Chapel, that he ‘had grown up in the Chapel under Cornish’, and that ‘as dramatist and Court-entertainer’ he ‘was naturally associated with the performances of the Chapel’.[89] There is no proof whatever that Heywood began as a Chapel boy, and although he certainly wrote plays for boys, they are nowhere said or implied to have been of the Chapel company. There are scraps of evidence which indicate that they may have been the Paul’s boys.[90] It is also conceivable that they may have been Philip van Wilder’s young minstrels.

When Elizabeth came to the throne, then, the Chapel had already a considerable dramatic tradition behind it. But for a decade its share in the Court revels remains somewhat obscure. The Treasurer of the Chamber records no payments for performances to its Masters before 1568.[91] A note in a Revels inventory of 1560 of the employment of some white sarcenet ‘in ffurnishinge of a pley by the children of the Chapple’ may apparently refer to any year from 1555 to 1560, and it is therefore hazardous to identify the Chapel with the anonymous players of the interlude of 31 December 1559 which contained ‘suche matter that they wher commondyd to leyff off’.[92] Bower may of course have retained[33] Catholic sympathies, but he died on 26 July 1561, and it is difficult to suppose that the high dramatic reputation of his successor Richard Edwardes was not based upon a greater number of Court productions than actually stand to his name.[93] Edwardes had been a Gentleman of the Chapel from 1556 or earlier. His patent as Master is dated on 27 October 1561, and on the following 10 December he received a commission the terms of which served as a model for those of the next two Masterships:[94]

Memorandum quod xo die Januarii anno infra scripto istud breve deliberatum fuit domino custodi magni Sigilli apud Westmonasterium exequendum.

Elizabeth by the grace of God Quene of England Fraunce & Ireland defender of the faythe &c. To our right welbeloved & faythfull counsaylour Sir Nicholas Bacon knight Keper of our great Seale of Englande, commaundinge you that vnder our great Seale aforsayd ye cause to be made our lettres patentes in forme followinge. To all mayours sherifs bayliefes constables & all other our officers gretinge. For that it is mete that our chappell royall should be furnysshed with well singing children from tyme to tyme we have & by these presentes do authorise our welbeloved servaunt Richard Edwardes master of our children of our sayd chappell or his deputie beinge by his bill subscribed & sealed so authorised, & havinge this our presente comyssion with hym, to take as manye well singinge children as he or his sufficient deputie shall thinke mete in all chathedrall & collegiate churches as well within libertie[s] as without within this our realme of England whatsoever they be, And also at tymes necessarie, horses, boates, barges, cartes, & carres, as he for the conveyaunce of the sayd children from any place to our sayd chappell royall [shall thinke mete] with all maner of necessaries apperteynyng to the sayd children as well by lande as water at our prices ordynarye to be redely payed when they for our service shall remove to any place or places, Provided also that if our sayd servaunt or his deputie or deputies bearers hereof in his name cannot forthwith remove the chyld or children when he by vertue of this our commyssyon hathe taken hym or them that then the sayd child or children shall remayne there vntill suche tyme as our sayd servaunt Rychard Edwardes shall send for him or them. Wherfore we will & commaunde you & everie of you to whom this our comyssion shall come to be helpinge aydinge & assistinge to the vttermost of your powers as ye[34] will answer at your vttermoste perylles. In wytnes wherof &c. Geven vnder our privie seale at our Manor of St James the fourth daye of Decembre in the fourth yere of our Raigne.

R. Jones.

At Christmas 1564–5 the boys appeared at Court in a tragedy by Edwardes, which may have been his extant Damon and Pythias.[95] On 2 February 1565 and 2 February 1566 they gave performances before the lawyers at the Candlemas feasts of Lincoln’s Inn.[96] There is nothing to show that the Chapel had any concern with the successful play of Palamon and Arcite, written and produced by Edwardes for Elizabeth’s visit to Oxford in September 1566. Edwardes died on the following 31 October, and on 15 November William Hunnis was appointed Master of the Children.[97] His formal patent of appointment is dated 22 April 1567, and the bill for his commission, which only differs from that of Edwardes in minor points of detail, on 18 April.[98] Hunnis had been a Gentleman at least since about 1553, with an interval of disgrace under Mary, owing to his participation in Protestant plots. He was certainly himself a dramatist, but none of his plays are known to be extant, and a contemporary eulogy speaks of his ‘enterludes’ as if they dated from an earlier period than that of his Mastership. It is, however, natural to suppose that he may have had a hand in some at least of the pieces which his Children produced at Court. The first of these was a tragedy at Shrovetide 1568. In the following year is said to have been published a pamphlet entitled The Children of the Chapel Stript and Whipt, which apparently originated in some gross offence given by the dramatic activities of the Chapel to the growing Puritan sentiment. ‘Plaies’, said the writer, ‘will never be supprest, while her maiesties unfledged minions flaunt it in silkes and sattens. They had as well be at their Popish service, in the deuils garments.’ And again, ‘Even in her maiesties chappel do these pretty upstart youthes profane the Lordes Day by the[35] lascivious writhing of their tender limbs, and gorgeous decking of their apparell, in feigning bawdie fables gathered from the idolatrous heathen poets’. I should feel more easy in drawing inferences from this, were the book extant.[99] But it seems to indicate either that the controversialist of 1569 was less careful than his successors to avoid attacks upon Elizabeth’s private ‘solace’, or that the idea had already occurred to the Master of turning his rehearsals of Court plays to profit by giving open performances in the Chapel. That the Court performances themselves took place in the Chapel is possible, but not very likely; the usual places for them seem to have been the Hall or the Great Chamber.[100] But no doubt they sometimes fell on a Sunday.

The boys played at Court on 6 January 1570 and during Shrovetide 1571. On 6 January 1572 they gave Narcissus, and on 13 February 1575 a play with a hunt in it.[101] On all these occasions Hunnis was payee. An obvious error of the clerk of the Privy Council in entering him as ‘John’ Hunnis in connexion with the issue of a warrant for the payment of 1572 led Chalmers to infer the existence of two Masters of the name of Hunnis.[102] During the progress of 1575 Hunnis contributed shows to the ‘Princely Pleasures’ of Kenilworth, and very likely utilized the services of the boys in these.[103] And herewith his active conduct of the Chapel performances appears to have been suspended for some years. A play of Mutius Scaevola, given jointly at Court by the Children of the Chapel and the Children of Windsor on 6 January 1577, is the first of a series for which the place of Hunnis as payee is taken by Richard Farrant. To this series belong unnamed plays on 27 December 1577 and 27 December 1578, Loyalty and Beauty on 2 March 1579, and Alucius on 27 December[36] 1579.[104] Farrant, who is known as a musician, had been a Gentleman of the Chapel in 1553, and had left on 24 April 1564, doubtless to take up the post of Master of the Children of Windsor, in which capacity he annually presented a play at Court from 1566–7 to 1575–6.[105] But evidently the two offices were not regarded as incompatible, for on 5 November 1570, while still holding his Mastership, he was again sworn in as Gentleman of the Chapel ‘from Winsore’.[106] A recent discovery by M. Feuillerat enables us to see that his taking over of the Chapel Children from Hunnis in 1576 was part of a somewhat considerable theatrical enterprise. Stimulated perhaps by the example of Burbadge’s new-built Theatre, he took a lease of some of the old Priory buildings in the Blackfriars; and here, either for the first time, or in continuation of a similar use of the Chapel itself, which had provoked criticism, the Children appeared under his direction in performances open to the public.[107] The ambiguous relation of the Blackfriars precinct to the jurisdiction of the City Corporation probably explains the inclusion of the Chapel in the list of companies whose exercises the Privy Council instructed the City to tolerate on 24 December 1578. It is, I think, pretty clear that, although Farrant is described as Master of the Chapel Children by the Treasurer of the Chamber from 1577 to 1580, and by Hunnis himself in his petition of 1583,[108] he was never technically Master, but merely acted as deputy to Hunnis, probably even to the extent of taking all the financial risks off his hands. Farrant was paid for a comedy at Lincoln’s Inn at Candlemas 1580 and is described in the entry as ‘one of the Queen’s chaplains’.[109] On 30 November 1580 he died and Hunnis then resumed his normal functions.[110] The Chapel played at Court on 5 February 1581, 31 December 1581, 27 February 1582, and 26 December[37] 1582. One of these plays may have been Peele’s Arraignment of Paris; that of 26 December 1582 was A Game of Cards, possibly the piece which, according to Sir John Harington, was thought ‘somewhat too plaine’, and was championed at rehearsal by ‘a notable wise counseller’.[111] On the first three of these occasions the Treasurer merely entered a payment to the Master of the Children, without giving a name, but in the entry for the last play Hunnis is specified. It is known, moreover, that Hunnis, together with one John Newman, took a sub-lease of the Blackfriars from Farrant’s widow on 20 December 1581. They do not seem to have been very successful financially, for they were irregular in their rent, and neglected their repairs. It was perhaps trepidation at the competition likely to arise from the establishment of the Queen’s men in 1583, which led them to transfer their interest to one Henry Evans, a scrivener of London, from whom, when Sir William More took steps to protect himself against the breach of covenant involved in an alienation without his consent, it was handed on to the Earl of Oxford and ultimately to John Lyly.[112] In November 1583, therefore, Hunnis found himself much dissatisfied with his financial position, and drew up the following memorial, probably for submission to the Board of Green Cloth of the royal household:[113]

‘Maye it please your honores, William Hunnys, Mr of the Children of hir highnes Chappell, most humble beseecheth to consider of these fewe lynes. First, hir Maiestie alloweth for the dyett of xij children of hir sayd Chappell daylie vid a peece by the daye, and xlli by the yeare for theyre aparrell and all other furneture.

‘Agayne there is no ffee allowed neyther for the mr of the sayd children nor for his ussher, and yet neuertheless is he constrayned, over and besydes the ussher still to kepe bothe a man servant to attend upon them and lykewyse a woman seruant to wash and kepe them cleane.

‘Also there is no allowance for the lodginge of the sayd chilldren, such tyme as they attend vppon the Courte, but the mr to his greate charge is dryuen to hyer chambers both for himself, his usher chilldren and servantes.

‘Also theare is no allowaunce for ryding jornies when occasion serueth the mr to trauell or send into sundrie partes within this realme, to take vpp and bring such children as be thought meete to be trayned for the service of hir Maiestie.

‘Also there is no allowance ne other consideracion for those children whose voyces be chaunged, whoe onelye do depend vpon the charge of the sayd mr vntill such tyme as he may preferr the same with cloathing and other furniture, vnto his no smalle charge.

[38]

‘And although it may be obiected that hir Maiesties allowaunce is no whitt less then hir Maiesties ffather of famous memorie therefore allowed: yet considering the pryces of thinges present to the tyme past and what annuities the mr then hadd out of sundrie abbies within this realme, besydes sondrie giftes from the Kinge, and dyuers perticuler ffees besydes, for the better mayntenaunce of the sayd children and office: and besides also there hath ben withdrawne from the sayd chilldren synce hir Maiesties comming to the crowne xijd by the daye which was allowed for theyr breakefastes as may apeare by the Treasorer of the Chamber his acompt for the tyme beinge, with other allowaunces incident to the office as appeareth by the auntyent acomptes in the sayd office which I heere omytt.

‘The burden heerof hath from tyme to tyme so hindred the Mrs of the Children viz. Mr Bower, Mr Edwardes, my sellf and Mr Farrant: that notwithstanding some good helpes otherwyse some of them dyed in so poore case, and so deepelie indebted that they haue not left scarcelye wherewith to burye them.

‘In tender consideracion whereof, might it please your honores that the sayde allowaunce of vjd a daye apeece for the childrens dyet might be reserued in hir Maiesties coffers during the tyme of theyre attendaunce. And in liew thereof they to be allowed meate and drinke within this honorable householde for that I am not able vppon so small allowaunce eny longer to beare so heauie a burden. Or otherwyse to be consydred as shall seeme best vnto your honorable wysdomes.

‘[Endorsed] 1583 November. The humble peticion of the Mr of the Children of hir highnes Chappell [and in another hand] To have further allowances for the finding of the children for causes within mentioned.’