“PICKED UP SOME OF THE SHREDS”

BEING

INCIDENTS IN THE LIFE OF A PLAIN MAN

WHO TRIED TO DO HIS DUTY

BY

OCTAVE THANET

ILLUSTRATED BY

A. B. FROST AND CLIFFORD CARLETON

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1897

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

| PAGE | |

| THE MISSIONARY SHERIFF | 1 |

| THE CABINET ORGAN | 51 |

| HIS DUTY | 97 |

| THE HYPNOTIST | 131 |

| THE NEXT ROOM | 167 |

| THE DEFEAT OF AMOS WICKLIFF | 217 |

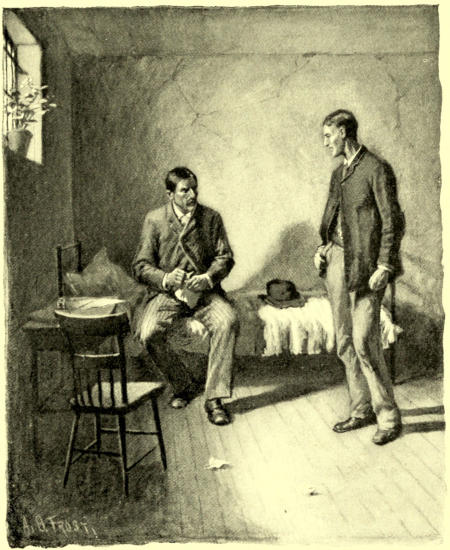

| “PICKED UP SOME OF THE SHREDS” | Frontispiece | |

| “TORE THE LETTER INTO PIECES” | Facing p. | 20 |

| THE THANKSGIVING BOX | ” | 30 |

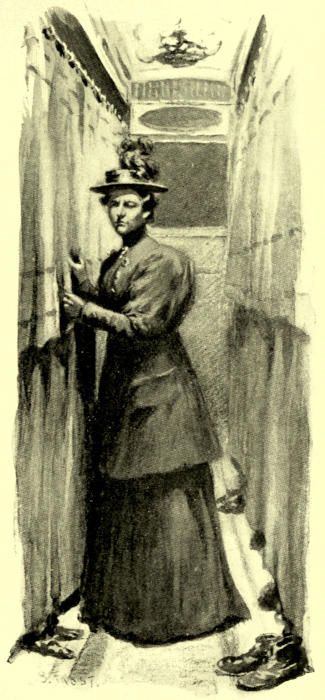

| “SHE PAUSED BEFORE MRS. SMITH’S SECTION” | ” | 46 |

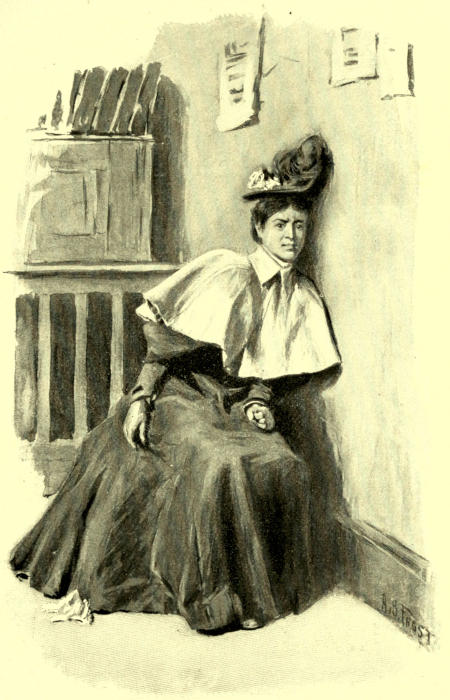

| “SHE LEANED HER SHABBY ELBOWS ON THE GATE” | ” | 56 |

| “‘SOMEBODY THREW THESE THINGS AT OUR WINDOW’” | ” | 70 |

| “‘NOW, BOYS, LET’S COME AND PLAY ON THE ORGAN’” | ” | 74 |

| “‘THEY HAVE ENGAGED ME’” | ” | 94 |

| “HARNED HID HIS FACE” | ” | 116 |

| “‘IT WON’T BE SUCH A BIG ONE IF THE DOOR HOLDS’” | ” | 126 |

| “‘SHE MUST LOOK AT IT’” | ” | 146 |

| “‘HE’S SCARED NOW, THE COWARD’” | ” | 158 |

| “‘I’LL ACT AS HIS VALET’” | ” | 162 |

| “‘I’LL GIVE THE KITTY SOMETHING TO EAT’” | ” | 180 |

| THE FAREWELL | ” | 232 |

Sheriff Wickliff leaned out of his office window, the better to watch the boy soldiers march down the street. The huge pile of stone that is the presumed home of Justice for the county stands in the same yard with the old yellow stone jail. The court-house is ornate and imposing, although a hundred active chimneys daub its eaves and carvings, but the jail is as plain as a sledge-hammer. Yet during Sheriff Wickliff’s administration, while Joe Raker kept jail and Mrs. Raker was matron, window-gardens brightened the grim walls all summer, and chrysanthemums and roses blazoned the black bars in winter.

Above the jail the street is a pretty street, with trim cottages and lawns and gardens; below, the sky-lines dwindle ignobly into shabby one and two story wooden shops devoted to the humbler handicrafts. It is not a street favored[4] by processions; only the little soldiers of the Orphans’ Home Company would choose to tramp over its unkempt macadam. Good reason they had, too, since thus they passed the sheriff’s office, and it was the sheriff who had given most of the money for their uniforms, and their drums and fifes outright.

A voice at the sheriff’s elbow caused him to turn.

“Well, Amos,” said his deputy, with Western familiarity, “getting the interest on your money?”

Wickliff smiled as he unbent his great frame; he was six feet two inches in height, with bones and thews to match his stature. A stiff black mustache, curving about his mouth and lifting as he smiled, made his white teeth look the whiter. One of the upper teeth was crooked. That angle had come in an ugly fight (when he was a special officer and detective) in the Chicago stock-yards, he having to hold a mob at bay, single-handed, to save the life of a wounded policeman. The scar seaming his jaw and neck belonged to the time that he captured a notorious gang of train-robbers. He brought the robbers in—that is, he brought their bodies; and “That scar was worth three thousand dollars to me,” he was wont to say. In point of fact it was[5] worth more, because he had invested the money so advantageously that, thanks to it and the savings which he had been able to add, in spite of his free hand he was now become a man of property. The sheriff’s high cheek-bones, straight hair (black as a dead coal), and narrow black eyes were the arguments for a general belief that an Indian ancestor lurked somewhere in the foliage of his genealogical tree. All that people really knew about him was that his mother died when he was a baby, and his father, about the same time, was killed in battle, leaving their only child to drift from one reluctant protector to another, until he brought up in the Soldiers’ Orphans’ Home of the State. If the sheriff’s eyes were Indian, Indians may have very gentle eyes. He turned them now on the deputy with a smile.

“Well, Joe, what’s up?” said he.

“The lightning-rod feller wants to see you, as soon as you come back to the jail, he says. And here’s something he dropped as he was going to his room. Don’t look much like it could be his mother. Must have prigged it.”

The sheriff examined the photograph, an ordinary cabinet card. The portrait was that of a woman, pictured with the relentless frankness of a rural photographer’s camera. Every sad line[6] in the plain elderly face, every wrinkle in the ill-fitting silk gown, showed with a brutal distinctness, and somehow made the picture more pathetic. The woman’s hair was gray and thin; her eyes, which were dark, looked straight forward, and seemed to meet the sheriff’s gaze. They had no especial beauty of form, but they, as well as the mouth, had an expression of wistful kindliness that fixed his eyes on them for a full minute. He sighed as he dropped his hand. Then he observed that there was writing on the reverse side of the carte, and lifted it again to read.

In a neat cramped hand was written:

“To Eddy, from Mother.

Feb. 21, 1889.

“The Lord bless thee and keep thee. The Lord make His face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee; the Lord lift up His countenance upon thee, and give thee peace.”

Wickliff put the carte in his pocket.

“That’s just the kind of mother I’d like to have,” said he; “awful nice and good, and not so fine she should be ashamed of me. And to think of him!”

“He’s an awful slick one,” assented the deputy, cordially. “Two years we’ve been ayfter him. New games all the time; but the lightning-rods[7] ain’t in it with this last scheme—working hisself off as a Methodist parson on the road to a job, and stopping all night, and then the runaway couple happening in, and that poor farmer and his wife so excited and interested, and of course they’d witness and sign the certificate; wisht I’d seen them when they found out!”

“They gave ’em cake and some currant wine, too.”

“That’s just like women. Say, I didn’t think the girl was much to brag on for looks—”

“Got a kinder way with her, though,” Wickliff struck in. “Depend on it, Joseph, the most dangerous of them all are the homely girls with a way to them. A man’s off his guard with them; he’s sorry for them not being pretty, and being so nice and humble; and before he knows it they’re winding him ’round their finger.”

“I didn’t know you was so much of a philosopher, Amos,” said the deputy, admiring him.

“It ain’t me, Joe; it’s the business. Being a philosopher, I take it, ain’t much more than seeing things with the paint off; and there’s nothing like being a detective to get the paint off. It’s a great business for keeping a man straight, too, seeing the consequences of wickedness so constantly, especially fool wickedness that gets found out. Well, Joe, if this lady”—touching[8] his breast pocket—“is that guy’s mother, I’m awful sorry for her, for I know she tried to train him right. I’ll go over and find out, I guess.”

So saying, and quite unconscious of the approving looks of his subordinate (for he was a simple-minded, modest man, who only spoke out of the fulness of his heart), the sheriff walked over to the jail.

The corridor into which the cells of the unconvicted prisoners opened was rather full to-day. As the sheriff entered, every one greeted him, even the sullen-browed man talking with a sobbing woman through the bars, and every one smiled. He nodded to all, but only spoke to the visitor. He said, “I guess he didn’t do it this time, Lizzie; he won’t be in long.”

“That’s what I bin tellin’ her,” growled the man, “and she won’t believe me; I told her I promised you—”

“And God A’mighty bless you, sheriff, for what you done!” the woman wailed. The sheriff had some ado to escape from her benedictions politely; but he got away, and knocked at the door of the last cell on the tier. The inmate opened the door himself.

He was a small man, who still was wearing the clerical habit of his last criminal masquerade;[9] and his face carried out the suggestion of his costume, being an actor’s face, not only in the clean-shaven cheeks and lips, but in the flexibility of the features and the unconscious alertness of gaze. He was fair of skin, and his light-brown hair was worn off his head at the temples. His eyes were fine, well shaped, of a beautiful violet color, and an extremely pleasant expression. He looked like a mere boy across the room in the shadow, but as he advanced, certain deep lines about his mouth displayed themselves and raised his age. The sunlight showed that he was thin; he was haggard the instant he ceased to smile. With a very good manner he greeted the sheriff, to whom he proffered the sole chair of the apartment.

“Guess the bed will hold me,” said the sheriff, testing his words by sitting down on the white-covered iron bedstead. “Well, I hear you wanted to see me.”

“Yes, sir. I want to get my money that you took away from me.”

“Well, I guess you can’t have it.” The sheriff spoke with a smile, but his black eyes narrowed a little. “I guess the court will have to decide first if that ain’t old man Goodrich’s money that you got from the note he supposed was a marriage certificate. I guess you better not put any[10] hopes on that money, Mr. Paisley. Wasn’t that the name you gave me?”

“Paisley’ll do,” said the other man, indifferently. “What became of my friend?”

“The sheriff of Hardin County wanted the man, and the lady—well, the lady is here boarding with me.”

“Going to squeal?”

“Going to tell all she knows.”

Paisley’s hand went up to his mouth; he changed color. “It’s like her,” he muttered—“oh, it’s just like her!” And he added a villanous epithet.

“None of that talk,” said Wickliff.

The man had jumped up and was pacing his narrow space, fighting against a climbing rage. “You see,” he cried, unable to contain himself—“you see, what makes me so mad is now I’ve got to get my mother to help me—and I’d rather take a licking!”

“I should think you would,” said Wickliff, dryly. “Say, this your mother?” He handed him the photograph, the written side upward.

“It came in a Bible,” explained Paisley, with an embarrassed air.

“Your mother rich?”

“She can raise the money.”

“Meaning, I expect, that she can mortgage[11] her house and lot. Look here, Smith, this ain’t the first time your ma has sent you money, but if I was you I’d have the last time stay the last. She don’t look equal to much more hard work.”

“My name’s Paisley, if you please,” returned the prisoner, stolidly, “and I can take care of my own mother. If she’s lent me money I have paid it back. This is only for bail, to deposit—”

“There is the chance,” interrupted Wickliff, “of your skipping. Now, I tell you, I like the looks of your mother, and I don’t mean she shall run any risks. So, if you do get money from her, I shall personally look out you don’t forfeit your bail. Besides, court is in session now, so the chances are you wouldn’t more than get the money before it would be your turn. See?”

“Anyhow I’ve got to have a lawyer.”

“Can’t see why, young feller. I’ll give you a straight tip. There ain’t enough law in Iowa to get you out of this scrape. We’ve got the cinch on you, and there ain’t any possible squirming out.”

“So you say;” the sneer was a little forced; “I’ve heard of your game before. Nice, kind officers, ready to advise a man and pump him dry, and witness against him afterwards. I ain’t that kind of a sucker, Mr. Sheriff.”

“Nor I ain’t that kind of an officer, Mr. Smith.[12] You’d ought to know about my reputation by this time.”

“They say you’re square,” the prisoner admitted; “but you ain’t so stuck on me as to care a damn whether I go over the road; expect you’d want to send me for the trouble I’ve given you,” and he grinned. “Well, what are you after?”

“Helping your mother, young feller. I had a mother myself.”

“It ain’t uncommon.”

“Maybe a mother like mine—and yours—is, though.”

The prisoner’s eyes travelled down to the face on the carte. “That’s right,” he said, with another ring in his voice. “I wouldn’t mind half so much if I could keep my going to the pen from her. She’s never found out about me.”

“How much family you got?” said Wickliff, thoughtfully.

“Just a mother. I ain’t married. There was a girl, my sister—good sort too, ’nuff better’n me. She used to be a clerk in the store, type-writer, bookkeeper, general utility, you know. My position in the first place; and when I—well, resigned, they gave it to her. She helped mother buy the place. Two years ago she died. You may believe me or not, but I would have gone[13] back home then and run straight if it hadn’t been for Mame. I would, by ⸺! I had five hundred dollars then, and I was going back to give every damned cent of it to ma, tell her to put it into the bakery—”

“That how she makes a living?”

“Yes—little two-by-four bakery—oh, I’m giving you straight goods—makes pies and cakes and bread—good, too, you bet—makes it herself. Ruth Graves, who lives round the corner, comes in and helps—keeps the books, and tends shop busy times; tends the oven too, I guess. She was a great friend of Ellie’s—and mine. She’s a real good girl. Well, I didn’t get mother’s letters till it was too late, and I felt bad; I had a mind to go right down to Fairport and go in with ma. That—she stopped it. Got me off on a tear somehow, and by the time I was sober again the money was ’most all gone. I sent what was left off to ma, and I went on the road again myself. But she’s the devil.”

“That the time you hit her?”

The prisoner nodded. “Oughtn’t to, of course. Wasn’t brought up that way. My father was a Methodist preacher, and a good one. But I tell you the coons that say you never must hit a woman don’t know anything about that sort of women; there ain’t nothing on earth so infernally[14] exasperating as a woman. They can mad you worse than forty men.”

It was the sheriff’s turn to nod, which he did gravely, with even a glimmer of sympathy in his mien.

“Well, she never forgave you,” said he; “she’s had it in for you since.”

“And she knows I won’t squeal, ’cause I’d have to give poor Ben away,” said the prisoner; “but I tell you, sheriff, she was at the bottom of the deviltry every time, and she managed to bag the best part of the swag, too.”

“I dare say. Well, to come back to business, the question with you is how to keep these here misfortunes of yours from your mother, ain’t it?”

“Of course.”

“Well, the best plan for you is to plead guilty, showing you don’t mean to give the court any more trouble. Tell the judge you are sick of your life, and going to quit. You are, ain’t you?” the sheriff concluded, simply; and the swindler, after an instant’s hesitation, answered:

“Damned if I won’t, if I can get a job!”

“Well, that admitted”—the sheriff smoothed his big knees gently as he talked, his mild attentive eyes fixed on the prisoner’s nervous presence—“that admitted, best plan is for you to plead guilty, and maybe we can fix it so’s you[15] will be sentenced to jail instead of the pen. Then we can keep it from your mother easy. Write her you’ve got a job here in this town, and have your letters sent to my care. I’ll get you something to do. She’ll never suspect that you are the notorious Ned Paisley. And it ain’t likely you go home often enough to make not going awkward.”

“I haven’t been home in four years. But see here: how long am I likely to get?”

The sheriff looked at him, at the hollow cheeks and sunken eyes and narrow chest—all so cruelly declared in the sunshine; and unconsciously he modulated his voice when he spoke.

“I wouldn’t worry about that, if I was you. You need a rest. You are run down pretty low. You ain’t rugged enough for the life you’ve been leading.”

The prisoner’s eyes strayed past the grating to the green hills and the pleasant gardens, where some children were playing. The sheriff did not move. There was as little sensibility in his impassive mask as in a wooden Indian’s; but behind the trained apathy was a real compassion. He was thinking. “The boy don’t look like he had a year’s life in him. I bet he knows it himself. And when he stares that way out of the window he’s thinking he ain’t never going to be[16] foot-loose in the sun again. Kinder tough, I call it.”

The young man’s eyes suddenly met his. “Well, it’s no great matter, I guess,” said he. “I’ll do it. But I can’t for the life of me make out why you are taking so much trouble.”

He was surprised at Wickliff’s reply. It was, “Come on down stairs with me, and I’ll show you.”

“You mean it?”

“Yes; go ahead.”

“You want my parole not to cut and run?”

“Just as you like about that. Better not try any fooling.”

The prisoner uttered a short laugh, glancing from his own puny limbs to the magnificent muscles of the officer.

“Straight ahead, after you’re out of the corridor, down-stairs, and turn to the right,” said Wickliff.

Silently the prisoner followed his directions, and when they had descended the stairs and turned to the right, the sheriff’s hand pushed beneath his elbow and opened the door before them. “My rooms,” said Wickliff. “Being a single man, it’s handier for me living in the jail.” The rooms were furnished with the unchastened gorgeousness of a Pullman sleeper, the[17] brilliant hues of a Brussels carpet on the floor, blue plush at the windows and on the chairs. The walls were hung with the most expensive gilt paper that the town could furnish (after all, it was a modest price per roll), and against the gold, photographs of the district judges assumed a sinister dignity. There was also a photograph of the court-house, and one of the jail, and a model in bas-relief of the Capitol at Des Moines; but more prominent than any of these were two portraits opposite the windows. They were oil-paintings, elaborately framed, and they had cost so much that the sheriff rested happily content that they must be well painted. Certainly the artist had not recorded impressions; rather he seemed to have worked with a microscope, not slighting an eyelash. One of the portraits was that of a stiff and stern young man in a soldier’s uniform. He was dark, and had eyes and features like the sheriff. The other was the portrait of a young girl. In the original daguerreotype from which the artist worked the face was comely, if not pretty, and the innocence in the eyes and the timid smile made it winning. The artist had enlarged the eyes and made the mouth smaller, and bestowed (with the most amiable intentions) a complexion of hectic brilliancy; but there still remained, in spite of paint, a flicker of[18] the old touching expression. Between the two canvases hung a framed letter. It was labelled in bold Roman script, “Letter of Capt. R. T. Manley,” and a glance showed the reader that it was the description of a battle to a friend. One sentence was underlined. “We also lost Private A. T. Wickliff, killed in the charge—a good man who could always be depended on to do his duty.”

The sheriff guided his bewildered visitor opposite these portraits and lifted his hand above the other’s shoulder. “You see them?” said he. “They’re my father and mother. You see that letter? It was wrote by my father’s old captain and sent to me. What he says about my father is everything that I know. But it’s enough. He was ‘a good man who could always be depended on to do his duty.’ You can’t say no more of the President of the United States. I’ve had a pretty tough time of it in my own life, as a man’s got to have who takes up my line; but I’ve tried to live so my father needn’t be ashamed of me. That other picture is my mother. I don’t know nothing about her, nothing at all; and I don’t need to—except those eyes of hers. There’s a look someway about your mother’s eyes like mine. Maybe it’s only the look one good woman has like another; but whatever it is, your mother made me think of mine. She’s the kind[19] of mother I’d like to have; and if I can help it, she sha’n’t know her son’s in the penitentiary. Now come on back.”

As silently as he had gone, the prisoner followed the sheriff back to his cell. “Good-bye, Paisley,” said the sheriff, at the door.

“Good-bye, sir; I’m much obliged,” said the prisoner. Not another word was said.

That evening, however, good Mrs. Raker told the sheriff that, to her mind, if ever a man was struck with death, that new young fellow was; and he had been crying, too; his eyes were all red.

“He needs to cry,” was all the comfort that the kind soul received from the sheriff, the cold remark being accompanied by what his familiars called his Indian scowl.

Nevertheless, he did his utmost for the prisoner as a quiet intercessor, and his merciful prophecy was accomplished—Edgar S. Paisley was permitted to serve out his sentence in the jail instead of the State prison. His state of health had something to do with the judge’s clemency, and the sheriff could not but suspect that, in his own phrase, “Paisley played his cough and his hollow cheeks for all they were worth.”

“But that’s natural,” he observed to Raker, “and he’s doing it partially for the old lady. Well, I’ll try to give her a quiet spell.”

“Yes,” Raker responds, dubiously, “but he’ll be at his old games the minute he gits out.”

“You don’t suppose”—the sheriff speaks with a certain embarrassment—“you don’t suppose there’d be any chance of really reforming him, so as he’d stick?—he ain’t likely to live long.”

“Nah,” says the unbelieving deputy; “he’s a deal too slick to be reformed.”

The sheriff’s pucker of his black brows and his slow nod might have meant anything. Really he was saying to himself (Amos was a dogged fellow): “Don’t care; I’m going to try. I am sure ma would want me to. I ain’t a very hefty missionary, but if there is such a thing as clubbing a man half-way decent, and I think there is, I’ll get him that way. Poor old lady, she looked so unhappy!”

During the trial, Paisley was too excited and dejected to write to his mother. But the day after he received his sentence the sheriff found him finishing a large sheet of foolscap.

It contained a detailed and vivid description of the reasons why he had left a mythical grocery firm, and described with considerable humor the mythical boarding-house where he was waiting for something to turn up. It was very well done, and he expected a smile from the sheriff. The red mottled his pale cheeks when Wickliff, with[21] his blackest frown, tore the letter into pieces, which he stuffed into his pocket.

“TORE THE LETTER INTO PIECES”

“You take a damned ungentlemanly advantage of your position,” fumed Paisley.

“I shall take more advantage of it if you give me any sass,” returned Wickliff, calmly. “Now set down and listen.” Paisley, after one helpless glare, did sit down. “I believe you fairly revel in lying. I don’t. That’s where we differ. I think lies are always liable to come home to roost, and I like to have the flock as small as possible. Now you write that you are here, and you’re helping me. You ain’t getting much wages, but they will be enough to keep you—these hard times any job is better than none. And you can add that you don’t want any money from her. Your other letter sorter squints like you did. You can say you are boarding with a very nice lady—that’s Mrs. Raker—everything very clean, and the table plain but abundant. Address you in care of Sheriff Amos T. Wickliff. How’s that?”

Paisley’s anger had ebbed away. Either from policy or some other motive he was laughing now. “It’s not nearly so interesting in a literary point of view, you know,” said he, “but I guess it will be easier not to have so many things to remember. And you’re right; I[22] didn’t mean to hint for money, but it did look like it.”

“He did mean to hint,” thought the sheriff, “but he’s got some sense.” The letter finally submitted was a masterpiece in its way. This time the sheriff smiled, though grimly. He also gave Paisley a cigar.

Regularly the letters to Mrs. Smith were submitted to Wickliff. Raker never thought of reading them. The replies came with a pathetic promptness. “That’s from your ma,” said Wickliff, when the first letter came—Paisley was at the jail ledgers in the sheriff’s room, as it happened, directly beneath the portraits—“you better read it first.”

Paisley read it twice; then he turned and handed it to the sheriff, with a half apology. “My mother talks a good deal better than she writes. Women are naturally interested in petty things, you know. Besides, I used to be fond of the old dog; that’s why she writes so much about him.”

“I have a dog myself,” growled the sheriff. “Your mother writes a beautiful letter.” His eyes were already travelling down the cheap thin note-paper, folded at the top. “I know,” Mrs. Smith wrote, in her stiff, careful hand—“I know you will feel bad, Eddy, to hear that dear old[23] Rowdy is gone. Your letter came the night before he died. Ruth was over, and I read it out loud to her; and when I came to that part where you sent your love to him, it seemed like he understood, he wagged his tail so knowing. You know how fond of you he always was. All that evening he played round—more than usual—and I’m so glad we both petted him, for in the morning we found him stiff and cold on the landing of the stairs, in his favorite place. I don’t think he could have suffered any, he looked so peaceful. Ruth and I made a grave for him in the garden, under the white rose tree. Ruth digged the grave, and she painted a Kennedy’s cracker-box, and we wrapped him up in white cotton cloth. I cried, and Ruth cried too, when we laid him away. Somehow it made me long so much more to see you. If I sent you the money, don’t you think you could come home for Christmas? Wouldn’t your employer let you if he knew your mother had not seen you for four years, and you are all the child she has got? But I don’t want you to neglect your business.”

The few words of affection that followed were not written so firmly as the rest. The sheriff would not read them; he handed the letter back to Paisley, and turned his Indian scowl on the back of the latter’s shapely head.

Paisley was staring at the columns of the page before him. “Rowdy was my dog when I was courting Ruth,” he said. “I was engaged to her once. I suppose mother thinks of that. Poor Rowdy! the night I ran away he followed me, and I had to whip him back.”

“Oh, you ran away?”

“Oh yes; the old story. Trusted clerk. Meant to return the money. It wasn’t very much. But it about cleaned mother out. Then she started the bakery.”

“You pay your ma back?”

“Yes, I did.”

“That’s a lie.”

“What do you ask a man such questions for, then? Do you think it’s pleasant admitting what a dirty dog you’ve been? Oh, damn you!”

“You do see it, then,” said the sheriff, in a very pleasant, gentle tone; “that’s one good thing. For you have got to reform, Ned; I’m going to give your mother a decent boy. Well, what happened then? Girl throw you over?”

“Why, I ran straight for a while,” said Paisley, furtively wiping first one eye and then the other with a finger; “there wasn’t any scandal. Ruth stuck by me, and a married sister of hers (who didn’t know) got her husband to give me a place. I was doing all right, and—and sending home[25] money to ma, and I would have been all right now, if—if—I hadn’t met Mame, and she made a crazy fool of me. Then Ruth shook me. Oh, I ain’t blaming her! It was hearing about Mame. But after that I just went a-flying to the devil. Now you know why I wanted to see Mame.”

“You wanted to kill her,” said the sheriff, “or you think you did. But you couldn’t; she’d have talked you over. Still, I thought I wouldn’t risk it. You know she’s gone now?”

“I supposed she’d be, now the trial’s over.” In a minute he added: “I’m glad I didn’t touch her; mother would have had to know that. Look here; how am I going to get over that invitation?”

“I’ll trust you for that lie,” said Wickliff, sauntering off.

Paisley wrote that he would not take his mother’s money. When he could come home on his own money he would gladly. He wrote a long affectionate letter, which the sheriff read, and handed back with the dry comment, “That will do, I guess.”

But he gave Paisley a brier-wood pipe and a pound of Yale Mixture that afternoon.

The correspondence threw some side-lights on Paisley’s past.

“You’ve got to write your ma every week,” announced Wickliff, when the day came round.

“Why, I haven’t written once a month.”

“Probably not, but you have got to write once a week now. Your mother’ll get used to it. I should think you’d be glad to do the only thing you can for the mother that’s worked her fingers off for you.”

“I am glad,” said Paisley, sullenly.

He never made any further demur. He wrote very good letters; and more and more, as the time passed, he grew interested in the correspondence. Meanwhile he began to acquire (quite unsuspected by the sheriff) a queer respect for that personage. The sheriff was popular among the prisoners; perhaps the general sentiment was voiced by one of them, who exclaimed, one day, after his visit, “Well, I never did see a man as had killed so many men put on so little airs!”

Paisley began his acquaintance with a contempt for the slow-moving intellect that he attributed to his sluggish-looking captor. He felt the superiority of his own better education. It was grateful to his vanity to sneer in secret at Wickliff’s slips in grammar or information. And presently he had opportunity to indulge his humor in this respect, for Wickliff began lending[27] him books. The jail library, as a rule, was managed by Mrs. Raker. She was, she used to say, “a great reader,” and dearly loved “a nice story that made you cry all the way through and ended right.” Her taste was catholic in fiction (she never read anything else), and her favorites were Mrs. Southworth, Charles Dickens, and Walter Scott. The sheriff’s own reading seldom strayed beyond the daily papers, but with the aid of a legal friend he had selected some standard biographies and histories to add to the singular conglomeration of fiction and religion sent to the jail by a charitable public. On Paisley’s request for reading, the sheriff went to Mrs. Raker. She promptly pulled Ishmael Worth, or Out of the Depths, from the shelf. “It’s beautiful,” says she, “and when he gits through with that he can have the Pickwick Papers to cheer him up. Only I kinder hate to lend that book to the prisoners; there’s so much about good eatin’ in it, it makes ’em dissatisfied with the table.”

“He’s got to have something improving, too,” says the sheriff. “I guess the history of the United States will do; you’ve read the others, and know they’re all right. I’ll run through this.”

He told Paisley the next morning that he had[28] sat up almost all night reading, he was so afraid that enough of the thirteen States wouldn’t ratify the Constitution. This was only one of the artless comments that tickled Paisley. Yet he soon began to notice the sheriff’s keenness of observation, and a kind of work-a-day sense that served him well. He fell to wondering, during those long nights when his cough kept him awake, whether his own brilliant and subtle ingenuity had done as much for him. He could hardly tell the moment of its beginning, but he began to value the approval of this big, ignorant, clumsy, strong man.

Insensibly he grew to thinking of conduct more in the sheriff’s fashion; and his letters not only reflected the change in his moral point of view, they began to have more and more to say of the sheriff. Very soon the mother began to be pathetically thankful to this good friend of her boy, whose habits were so correct, whose influence so admirable. In her grateful happiness over the frequent letters and their affection were revealed the unexpressed fears that had tortured her for years. She asked for Wickliff’s picture. Paisley did not know that the sheriff had a photograph taken on purpose. Mrs. Smith pronounced him “a handsome man.” To be sure, the unscarred side of his face was taken. “He[29] looks firm, too,” wrote the poor mother, whose own boy had never known how to be firm; “I think he must be a Daniel.”

“A which?” exclaimed the puzzled Daniel.

“Didn’t you ever go to Sunday-school? Don’t you know the verses,

The sheriff’s reply was enigmatical. It was: “Well, to think of you having such a mother as that!”

“I don’t deserve her, that’s a fact,” said Paisley, with his flippant air. “And yet, would you believe it, I used to be the model boy of the Sunday-school. Won all the prizes. Ma’s got them in a drawer.”

“Dare say. They thought you were a awful good boy, because you always kept your face clean and brushed your hair without being told to, and learned your lessons quick, and always said ‘Yes, ’m,’ and ‘No, ’m,’ and when you got into a scrape lied out of it, and picked up bad habits as easy and quiet as a long-haired dog catches fleas. Oh, I know your sort of model boy! We had ’em at the Orphans’ Home; I’ve taken their lickings, too.”

Paisley’s thin face was scarlet before the speech[30] was finished. “Some of that is true,” said he; “but at least I never hit a fellow when he was down.”

The sheriff narrowed his eyes in a way that he had when thinking; he put both hands in his pockets and contemplated Paisley’s irritation. “Well, young feller, you have some reason to talk that way to me,” said he. “The fact is, I was mad at you, thinking about your mother. I—I respect that lady very highly.”

Paisley forced a feeble smile over his “So do I.”

But after this episode the sheriff’s manner visibly softened to the young man. He told Raker that there were good spots in Paisley.

“Yes, he’s mighty slick,” said Raker.

Thanksgiving-time, a box from his mother came to the prisoner, and among the pies and cakes was an especial pie for Mr. Wickliff, “From his affectionate old friend, Rebecca Smith.”

THE THANKSGIVING BOX

The sheriff spent fully two hours communing with a large new Manual of Etiquette and Correspondence; then he submitted a letter to Paisley. Paisley read:

“Dear Madam,—Your favor (of the pie) of the 24th inst. is received and I beg you to accept my sincere and warm thanks. Ned is an efficient clerk and his habits[31] are very correct. We are reading history, in our leisure hours. We have read Fisk’s Constitutional History of the United States and two volumes of Macaulay’s History of England. Both very interesting books. I think that Judge Jeffreys was the meanest and worst judge I ever heard of. My early education was not as extensive as I could wish, and I am very glad of the valuable assistance which I receive from your son. He is doing well and sends his love. Hoping, my dear Madam, to be able to see you and thank you personally for your very kind and welcome gift, I am, with respect,

“Very Truly Yours,

“Amos T. Wickliff.”

Paisley read the letter soberly. In fact, another feeling destroyed any inclination to smile over the unusual pomp of Wickliff’s style. “That’s out of sight!” he declared. “It will please the old lady to the ground. Say, I take it very kindly of you, Mr. Wickliff, to write about me that way.”

“I had a book to help me,” confessed the flattered sheriff. “And—say, Paisley, when you are writing about me to your ma, you better say Wickliff, or Amos. Mr. Wickliff sounds kinder stiff. I’ll understand.”

The letter that the sheriff received in return he did not show to Paisley. He read it with a knitted brow, and more than once he brushed his hand across his eyes. When he finished it[32] he drew a long sigh, and walked up to his mother’s portrait. “She says she prays for me every night, ma”—he spoke under his breath, and reverently. “Ma, I simply have got to save that boy for her, haven’t I?”

That evening Paisley rather timidly approached a subject which he had tried twice before to broach, but his courage had failed him. “You said something, Mr. Wickliff, of paying me a little extra for what I do, keeping the books, etc. Would you mind telling me what it will be? I—I’d like to send a Christmas present to my mother.”

“That’s right,” said the sheriff, heartily. “I was thinking what would suit her. How’s a nice black dress, and a bill pinned to it to pay for making it up?”

“But I never—”

“You can pay me when you get out.”

“Do you think I’ll ever get out?” Paisley’s fine eyes were fixed on Wickliff as he spoke, with a sudden wistful eagerness. He had never alluded to his health before, yet it had steadily failed. Now he would not let Amos answer; he may have flinched from any confirmation of his own fears; he took the word hastily. “Anyhow, you’ll risk my turning out a bad investment. But you’ll do a damned kind action[33] to my mother; and if I’m a rip, she’s a saint.”

“Sure,” said the sheriff. “Say, do you think she’d mind my sending her a hymn-book and a few flowers?”

Thus it came to pass that the tiny bakery window, one Christmas-day, showed such a crimson glory of roses as the village had never seen; and the widow Smith, bowing her shabby black bonnet on the pew rail, gave thanks and tears for a happy Christmas, and prayed for her son’s friend. She prayed for her son also, that he might “be kept good.” She felt that her prayer would be answered. God knows, perhaps it was.

That night before she went to bed she wrote to Edgar and to Amos. “I am writing to both my boys,” she said to Amos, “for I feel like you were my dear son too.”

When Amos answered this letter he did not consult the Manual. It was one day in January, early in the month, that he received the first bit of encouragement for his missionary work palpable enough to display to the scoffer Raker. Yet it was not a great thing either; only this: Paisley (already half an hour at work in the sheriff’s room) stopped, fished from his sleeve a piece of note-paper folded into the measure of a knife-blade, and offered it to the sheriff.

“See what Mame sent me,” said he; “just read it.”

There was a page of it, the purport being that the writer had done what she had through jealousy, which she knew now was unfounded; she was suffering indescribable agonies from remorse; and, to prove she meant what she said, if her darling Ned would forgive her she would get him out before a week was over. If he agreed he was to be at his window at six o’clock Wednesday night. The day was Thursday.

“How did you get this?” asked Amos. “Do you mind telling?”

“Not the least. It came in a coat. From Barber & Glasson’s. The one Mrs. Raker picked out for me, and it was sent up from the store. She got at it somehow, I suppose.”

“But how did you get word where to look?”

Paisley grinned. “Mame was here, visiting that fellow who was taken up for smashing a window, and pretended he was so hungry he had to have a meal in jail. Mame put him up to it, so she could come. She gave me the tip where to look then.”

“I see. I got on to some of those signals once. Well, did you show yourself Wednesday?”

“Not much!” He hesitated, and did not look[35] at the sheriff, scrawling initials on the blotting-pad with his pen. “Did you really think, Mr. Wickliff, after all you’ve done for me—and my mother—I would go back on you and get you into trouble for that—”

“’S-sh! Don’t call names!” Wickliff looked apprehensively at the picture of his mother. “Why didn’t you give me this before?”

“Because you weren’t here till this morning. I wasn’t going to give it to Raker.”

“What do you suppose she’s after?”

“Oh, she’s got some big scheme on foot, and she needs me to work it. I’m sick of her. I’m sick of the whole thing. I want to run straight. I want to be the man my poor mother thinks I am.”

“And I want to help you, Ned,” cried the sheriff. For the first time he caught the other’s hand and wrung it.

“I guess the Lord wants to help me too,” said Paisley, in a queer dry tone.

“Why—yes—of course he wants to help all of us,” said the sheriff, embarrassed. Then he frowned, and his voice roughened as he asked, “What do you mean by that?”

“Oh, you know what I mean,” said Paisley, smiling; “you’ve always known it. It’s been getting worse lately. I guess I caught cold.[36] Some mornings I have to stop two or three times when I dress myself, I have such fits of coughing.”

“Why didn’t you tell, and go to the hospital?”

“I wanted to come down here. It’s so pleasant down here.”

“Good—” The sheriff reined his tongue in time, and only said, “Look here, you’ve got to see a doctor!”

Therefore the encouragement to the missionary work was embittered by divers conflicting feelings. Even Raker was disturbed when the doctor announced that Paisley had pneumonia.

“Double pneumonia and a slim chance, of course,” gloomed Raker. “Always so. Can’t have a man git useful and be a little decent, but he’s got to die! Why couldn’t it ’a’ been that tramp tried to set the jail afire?”

“What I’m a-thinking of is his poor ma, who used to write him such beautiful letters,” said Mrs. Raker, wiping her kind eyes. “They was so attached. Never a week he didn’t write her.”

“It’s his mother I’m thinking of, too,” said the sheriff, with a groan; “she’ll be wanting to come and see him, and how in—” He swallowed an agitated oath, and paced the floor, his hands clasped behind him, his lip under his teeth, and his blackest Indian scowl on his brow—plain[37] signs to all who knew him that he was fighting his way through some mental thicket.

But he had never looked gentler than he looked an hour later, as he stepped softly into Paisley’s cell. Mrs. Raker was holding a foaming glass to the sick man’s lips. “There; take another sup of the good nog,” she said, coaxingly, as one talks to a child.

“No, thank you, ma’am,” said Paisley. “Queer how I’ve thought so often how I’d like the taste of whiskey again on my tongue, and now I can have all I want, I don’t care a hooter!”

His voice was rasped in the chords, and he caught his breath between his sentences. Forty-eight hours had made an ugly alteration in his face; the eyes were glassy, the features had shrunken in an indescribable, ghastly way, and the fair skin was of a yellowish pallor, with livid circles about the eyes and the open mouth.

Wickliff greeted him, assuming his ordinary manner. They shook hands.

“There’s one thing, Mr. Wickliff,” said Paisley: “you’ll keep this from my mother. She’d worry like blazes, and want to come here.”

There was a photograph on the table, propped up by books; the sheriff’s hand was on it, and he moved it, unconsciously: “‘To Eddy, from Mother. The Lord bless and keep thee. The[38] Lord make his face to shine upon thee, and be gracious unto thee—’” Wickliff cleared his throat. “Well, I don’t know, Ned,” he said, cheerfully; “maybe that would be a good thing—kind of brace you up and make you get well quicker.”

Mrs. Raker noticed nothing in his voice; but Paisley rolled his eyes on the impassive face in a strange, quivering, searching look; then he closed them and feebly turned his head.

“Don’t you want me to telegraph? Don’t you want to see her?”

Some throb of excitement gave Paisley the strength to lift himself up on the pillows. “What do you want to rile me all up for?” His voice was almost a scream. “Want to see her? It’s the only thing in this damned fool world I do want! But I can’t have her know; it would kill her to know. You must make up some lie about it’s being diphtheria and awful sudden, and no time for her to come, and have me all out of the way before she gets here. You’ve been awful good to me, and you can do anything you like; it’s the last I’ll bother you—don’t let her find out!”

“For the land’s sake!” sniffed Mrs. Raker, in tears—“don’t she know?”

“No, ma’am, she don’t; and she never will,[39] either,” said the sheriff. “There, Ned, boy, you lay right down. I’ll fix it. And you shall see her, too. I’ll fix it.”

“Yes, he’ll fix it. Amos will fix it. Don’t you worry,” sobbed Mrs. Raker, who had not the least idea how the sheriff could arrange matters, but was just as confident that he would as if the future were unrolled before her gaze.

The prisoner breathed a long deep sigh of relief, and patted the strong hand at his shoulder. And Amos gently laid him back on the pillows.

Before nightfall Paisley was lying in Amos Wickliff’s own bed, while Amos, at his side, was critically surveying both chamber and parlor under half-closed eyelids. He was trying to see them with the eyes of the elderly widow of a Methodist minister.

“Hum—yes!” The result of the survey was, on the whole, satisfactory. “All nice, high-toned, first-class pictures. Nothing to shock a lady. Liquors all put away, ’cept what’s needed for him. Pops all put away, so she won’t be finding one and be killing herself, thinking it’s not loaded. My bed moved in here comfortable for him, because he thought it was such a pleasant room, poor boy. Another bed in my room for her. Bath-room next door, hot and cold water. Little gas stove. Trained nurse who[40] doesn’t know anything, and so can’t tell. Thinks it’s my friend Smith. Is there anything else?”

At this moment the white counterpane on the bed stirred.

“Well, Ned?” said Wickliff.

“It’s—nice!” said Paisley.

“That’s right. Now you get a firm grip on what I’m going to say—such a grip you won’t lose it, even if you get out of your head a little.”

“I won’t,” said Paisley.

“All right. You’re not Paisley any more. You’re Ned Smith. I’ve had you moved here into my rooms because your boarding-place wasn’t so good. Everybody here understands, and has got their story ready. The nurse thinks you’re my friend Smith. You are, too, and you are to call me Amos. The telegram’s gone. ’S-sh!—what a way to do!”—for Paisley was crying. “Ain’t I her boy too?”

One weak place remained in the fortress that Amos had builded against prying eyes and chattering tongues. He had searched in vain for “Mame.” There was no especial reason, except pure hatred and malice, to dread her going to Paisley’s mother, but the sheriff had enough knowledge of Mame’s kind to take these qualities into account.

From the time that Wickliff promised him[41] that he should have his mother, Paisley seemed to be freed from every misgiving. He was too ill to talk much, and much of the time he was miserably occupied with his own suffering; yet often during the night and day before she came he would lift his still beautiful eyes to Mrs. Raker’s and say, “It’s to-morrow night ma comes, isn’t it?” To which the soft-hearted woman would sometimes answer, “Yes, son,” and sometimes only work her chin and put her handkerchief to her eyes. Once she so far forgot the presence of the gifted professional nurse that she sniffed aloud, whereupon that personage administered a scorching tonic, in the guise of a glance, and poor Mrs. Raker went out of the room and cried.

He must have kept some reckoning of the time, for the next day he varied his question. He said, “It’s to-day she’s coming, isn’t it?” As the day wore on, the customary change of his disease came: he was relieved of his worst pain; he thought that he was better. So thought Mrs. Raker and the sheriff. The doctor and the nurse maintained their inscrutable professional calm. At ten o’clock the sheriff (who had been gone for a half-hour) softly opened the door. The sick man instantly roused. He half sat up. “I know,” he exclaimed; “it’s ma. Ma’s come!”

The nurse rose, ready to protect her patient.

There entered a little, black-robed, gray-haired woman, who glided swift as a thought to the bedside, and gathered the worn young head to her breast. “My boy, my dear, good boy!” she said, under her breath, so low the nurse did not hear her; she only heard her say, “Now you must get well.”

“Oh, I am glad, ma!” said the sick man.

After that the nurse was well content with them all. They obeyed her implicitly. It was she rather than Mrs. Raker who observed that Mr. Smith’s mother was not alone, but accompanied by a slim, fair, brown-eyed young woman, who lingered in the background, and would fain have not spoken to the invalid at all had she not been gently pushed forward by the mother, with the words, “And Ruth came too, Eddy!”

“Thank you, Ruth; I knew that you wouldn’t let ma come alone,” said Ned, feebly.

The young woman had opened her lips. Now they closed. She looked at him compassionately. “Surely not, Ned,” she said.

But why, wondered the nurse, who was observant—it was her trade to observe—why did she look at him so intently, and with such a shocked pity?

Ned did not express much—the sick, especially[43] the very sick, cannot; but whenever he waked in the night and saw his mother bending over him he smiled happily, and she would answer his thought. “Yes, my boy; my dear, good boy,” she would say.

And the sheriff in his dim corner thought sadly that the ruined life would always be saved for her now, and her son would be her good boy forever. Yet he muttered to himself, “I suppose the Lord is helping me out, and I ought to feel obliged, but I’m hanged if I wouldn’t rather take the chances and have the boy get well!”

But he knew all the time that there was no hope for Ned’s life. He lived three days after his mother came. The day before his death he was alone for a short time with the sheriff, and asked him to be good to his mother. “Ruth will be good to her too,” he said; “but last night I dreamed Mame was chasing mother, and it scared me. You won’t let her get at mother, will you?”

“Of course I won’t,” said the sheriff; “we’re watching your mother every minnit; and if that woman comes here, Raker has orders to clap her in jail. And I will always look out for your ma, Ned, and she never shall know.”

“That’s good,” said Ned, in his feeble voice. “I’ll tell you something: I always wanted to be[44] good, but I was always bad; but I believe I would have been decent if I’d lived, because I’d have kept close to you. You’ll be good to ma—and to Ruth?”

The sheriff thought that he had drifted away and did not hear the answer, but in a few moments he opened his eyes and said, brightly, “Thank you, Amos.” It was the first time that he had used the other man’s Christian name.

“Yes, Ned,” said the sheriff.

Next morning at daybreak he died. His mother was with him. Just before he went to sleep his mind wandered a little. He fancied that he was a little boy, and that he was sick, and wanted to say his prayers to his mother. “But I’m so sick I can’t get out of bed,” said he. “God won’t mind my saying them in bed, will He?” Then he folded his hands, and reverently repeated the childish rhyme, and so fell into a peaceful sleep, which deepened into peace. In this wise, perhaps, were answered many prayers.

Amos made all the arrangements the next day. He said that they were going home from Fairport on the day following, but he managed to conclude all the necessary legal formalities in time to take the evening train. Once on the train, and his companions in their sections, he drew a long breath.

“It may not have been Mame that I saw,” he said, taking out his cigar-case on the way to the smoking-room; “it was merely a glimpse—she in a buggy, me on foot; and it may be she wouldn’t do a thing or think the game worth blackmail; but I don’t propose to run any chances in this deal. Hullo—excuse me, miss!”

The last words were uttered aloud to Ruth Graves, who had touched him on the arm. He had a distinct admiration for this young woman, founded on the grounds that she cried very quietly, that she never was underfoot, and that she was so unobtrusively kind to Mrs. Smith.

“Anything I can do?” he began, with genuine willingness.

She motioned him to take a seat. “Mrs. Smith is safe in her section,” she said; “it isn’t that. I wanted to speak to you. Mr. Wickliff, Ned told me how it was. He said he couldn’t die lying to everybody, and he wanted me to know how good you were. I am perfectly safe, Mr. Wickliff,” as a look of annoyance puckered the sheriff’s brow. “He told me there was a woman who might some time try to make money out of his mother if she could find her, and I was to watch. Mr. Wickliff, was she rather tall and slim, with a fine figure?”

“Yes—dark-complected rather, and has a thin face and a largish nose.”

“And one of her eyes is a little droopy, and she has a gold filling in her front tooth? Mr. Wickliff, that woman got on this train.”

“She did, did she?” said the sheriff, showing no surprise. “Well, my dear young lady, I’m very much obliged to you. I will attend to the matter. Mrs. Smith sha’n’t be disturbed.”

“Thank you,” said the young woman; “that’s all. Good-night!”

“You might know that girl had had a business education,” the sheriff mused—“says what she’s got to say, and moves on. Poor Ned! poor Ned!”

Ruth went to her section, but she did not undress. She sat behind the curtains, peering through the opening at Mrs. Smith’s section opposite, or at the lower berth next hers, which was occupied by the sheriff. The curtains were drawn there also, and presently she saw him disappear by sections into their shelter. Then his shoes were pushed partially into the aisle. Empty shoes. She waited; it could not be that he was really going to sleep. But the minutes crept by; a half-hour passed; no sign of life behind his curtains. An hour passed. At the farther end of the car curtains parted, and a[47] young woman slipped out of her berth. She was dark and not handsome, but an elegant shape and a modish gown made her attractive-looking. One of her eyelids drooped a little.

“SHE PAUSED BEFORE MRS. SMITH’S SECTION”

She walked down the aisle and paused before Mrs. Smith’s section, Ruth holding her breath. She looked at the big shoes on the floor, her lip curling. Then she took the curtains of Mrs. Smith’s section in both hands and put her head in.

“I must stop her!” thought Ruth. But she did not spring out. The sheriff, fully dressed, was beside the woman, and an arm of iron deliberately turned her round.

“The game’s up, Mamie,” said Wickliff.

She made no noise, only looked at him.

“What are you going to do?” said she, with perfect composure.

“Arrest you if you make a racket, talk to you if you don’t. Go into that seat.” He indicated a seat in the rear, and she took it without a word. He sat near the aisle; she was by the window.

“I suppose you mean to sit here all night,” she remarked, scornfully.

“Not at all,” said he; “just to the next place. Then you’ll get out.”

“Oh, will I?”

“You will. Either you will get out and go about your business, or you will get out and be taken to jail.”

“We’re smart. What for?”

“For inciting prisoners to escape.”

“Ned’s dead,” with a sneer.

“Yes, he’s dead, and”—he watched her narrowly, although he seemed absorbed in buttoning his coat—“they say he haunts his old cell, as if he’d lost something. Maybe it’s the letter you folded up small enough to go in the seam of a coat. I’ve got that.” He saw that she was watching him in turn, and that she was nervous. “Ned’s dead, poor fellow, true enough; but—the girl at Barber & Glasson’s ain’t dead.”

She began to fumble with her gloves, peeling them off and rolling them into balls. He thought to himself that the chances were that she was superstitious.

“Look here,” he said, sharply, “have an end of this nonsense; you get off at the next place, and never bother that old lady again, or—I will have you arrested, and you can try for yourself whether Ned’s cell is haunted.”

For a brief space they eyed each other, she in an access of impotent rage, he stolid as the[49] carving of the seat. The car shivered; the great wheels moved more slowly. “Decide,” said he; not imperatively—dryly, without emotion of any sort. He kept his mild eyes on her.

“It wasn’t his mother I meant to tell; it was that girl—that nice girl he wanted to marry—”

“You make me tired,” said the sheriff. “Are you going, or am I to make a scene and take you? I don’t care much.”

She slipped her hand behind her into her pocket.

The sheriff laughed, and grasped one wrist.

“I don’t want to talk to the country fools,” she snapped.

“This way,” said the sheriff, guiding her. The train had stopped. She laughed as he politely handed her off the platform; the next moment the wheels were turning again and she was gone. He never saw her again.

The porter came out to stand by his side in the vestibule, watching the lights of the station race away and the darkling winter fields fly past. The sheriff was well known to him; he nodded an eager acquiescence to the officer’s request: “If those ladies in 8 and 9 ask you any questions, just tell them it was a crazy woman getting the wrong section, and I took care of her.”

Within the car a desolate mother wept the long night through, yet thanked God amid her tears for her son’s last good days, and did not dream of the blacker sorrow that had menaced her and had been hurled aside.

It was a June day. Not one of those perfervid June days that simulate the heat of July, and try to show the corn what June can do, but one of Shakespeare’s lovely and temperate days, just warm enough to unfurl the rose petals of the Armstrong rose-trees and ripen the grass flowers in the Beaumonts’ unmowed yard.

The Beaumonts lived in the north end of town, at the terminus of the street-car line. They did not live in the suburbs because they liked space and country air, nor in order to have flowers and a kitchen-garden of their own, like the Armstrongs opposite, but because the rent was lower. The Beaumonts were very poor and very proud. The Armstrongs were neither poor nor proud. Joel Armstrong, the head of the family, owned the comfortable house, with its piazzas and bay-windows, the small stable and the big yard. There was a yard enclosed in poultry-netting,[54] and a pasture for the cow, and the elderly family horse that had picked up so amazingly under the influence of good living and kindness that no one would suspect how cheaply the car company had sold him.

Armstrong was the foreman of a machine-shop. Every morning at half-past six Pauline Beaumont, who rose early, used to see him board the street-car in his foreman’s clothes, which differs from working-men’s clothes, though only in a way visible to the practised observer. He always was smoking a short pipe, and he usually was smiling. Mrs. Armstrong was a comely woman, who had a great reputation in the neighborhood as a cook and a nurse. In the family were three boys—if one can call the oldest a boy, who was a young carpenter, just this very day setting up for master-builder. The second boy was fifteen, and in the high-school, and the youngest was ten. There were no daughters; but for helper Mrs. Armstrong had a stout young Swede, who was occasionally seen by the Beaumonts hiding broken pieces of glass or china in a convenient ravine. The Beaumont house was much smaller than the Armstrongs’, nor was it in such admirable repair and paint; but then, as Henriette Beaumont was used to say, “They had not a carpenter in the family.”

It will be seen that the Beaumonts held themselves very high above the Armstrongs. They could not forget that twenty-five years ago their father had been Lieutenant-Governor, and they had been accounted rich people in the little Western city. Father and fortune had been lost long since. They were poor, obscure, working hard for a livelihood; but they still kept their pride, which only increased as their visible consequence diminished. Nevertheless, Pauline often looked wistfully across at the Armstrongs’ little feasts and fun, and always walked home on their side of the street. Pauline was the youngest and least proud of the Beaumonts.

To-day, as usual, she came down the street, past the neat low fence of the Armstrongs; but instead of passing, merely glancing in at the lawn and the house, she stopped; she leaned her shabby elbows on the gate, where she could easily see the dining-room and sniff the savory odors floating from the kitchen. “Oh, doesn’t it smell good?” she murmured. “Chickens fried, and new potatoes, and a strawberry shortcake. They have such a nice garden.” She caught her breath in a mirthless laugh. “How absurd I am! I feel like staying here and smelling the whole supper! Yesterday they had waffles, and the day before beefsteak—such lovely, hearty things!”

She was a tall girl, too thin for her height, with a pretty carriage and a delicate irregular face, too colorless and tired for beauty, but not for charm. Her skin was fine and clear, and her brown hair very soft. Her gray eyes were alight with interest as she watched the finishing touches given the table, which was spread with a glossy white cloth, and had a bowl of June roses in the centre. Mrs. Armstrong, in a new dimity gown and white apron, was placing a great platter of golden sponge-cake on the board. She looked up and saw Pauline. The girl could invent no better excuse for her scrutiny (which had such an air of prying) than to drop her head as if in faintness—an excuse, indeed, suggested by her own feelings. In a minute Mrs. Armstrong had stepped through the bay-window and was on the other side of the fence, listening with vivid sympathy to Pauline’s shamefaced murmur: “Excuse me, but I feel so ill!”

“It’s a rush of blood to the head,” cried Mrs. Armstrong, all the instincts of a nurse aroused. “Come right in; you mustn’t think of going home. Land! you’ll like as not faint before I can get over to you. Hold on to the fence if you feel things swimming!”

“SHE LEANED HER SHABBY ELBOWS ON THE GATE”

Pauline, in her confusion, grew red and redder, while, despite inarticulate protestations, she[57] was propelled into the house and on to a large lounge.

“Lay your head back,” commanded the nurse, appearing with an ammonia-bottle in one hand and a fan in the other.

“It’s nothing—nothing at all,” gasped Pauline, between shame and the fumes of ammonia. “The day was a little warm, and I walked home, and I was so busy I ate no lunch”—as if that were a change from her habits—“and all at once I felt faint. But I’m all right now.”

“Well, I don’t wonder you’re faint,” cried Mrs. Armstrong; “you oughtn’t to do that way. Now you just got to lie still—— Oh, that’s only Ikey. Ikey, you get a glass of wine for this lady; it’s Miss Beaumont.”

The tall young man in the gray suit and the blue flannel shirt blushed a little under his sunburn as he bowed. “Pleased to meet you, miss,” said he, promptly, before he disappeared.

“This is a great day for us,” continued the mother, releasing the ammonia from duty, and beginning to fan vigorously. “Ike has set up as master-builder—only two men, and he does most of the work; but he’s got a house all to himself, and the chance of some bigger ones. We’re having a little celebration. You must[58] excuse the paper on the lounge; I put it down when we unpacked the organ.”

“Oh, did the organ come?” said the son.

“It surely did, and we’ve played on it already.”

“Why, did you get the music? Was it in the box, too?”

“Oh, we ’ain’t played tunes; we just have been trying it—like to see how it goes. It’s got an awful sweet sound.”

“And you ought to hear me play a tune on it, ma.”

“You! For the land’s sake!”

“Yes, me—that never did play a tune in my life. Anybody can play on that organ.” He turned politely to Pauline, as to include her in the conversation. “You see, Miss Beaumont, we’re a musical family that can’t sing. We can’t, as they say, carry a tune to save our immortal souls. The trouble isn’t with the voice; it’s with our ears. We can hear well enough, too, but we haven’t an ear for music. I took lessons once, trying to learn to sing, but the teacher finally braced up to tell me that he hadn’t the conscience to take my money. ‘What’s the matter?’ says I. ‘You’ve lots of voice,’ says he, ‘but you haven’t a mite of ear.’ ‘Can’t anybody teach me to sing?’ says I. ‘Not[59] unless they hypnotize you, like Trilby,’ says he. So I gave it up. But next I thought I would learn to play; for if there’s one thing ma and the boys and I all love, it’s music. And just then, as luck would have it, this teacher wanted to sell his cabinet organ, which is in perfect shape and a fine instrument. And I was craving to buy it, but I knew it was ridiculous, when none of us can play. But I kept thinking. Finally it came to me. I had seen those zither things with numbers on them; why couldn’t he paint numbers on the keys of the organ just that way, and make music to correspond? And that’s just the way we’ve done. You’re very musical. I—I’ve often listened to your playing. What do you think of it?” He looked at her wistfully.

“I think it very ingenious—very,” said Pauline. She had risen now, and she thanked Mrs. Armstrong, and said she must go home. In truth, she was in a panic at the thought of what she had done. Henriette never would understand. Her heart beat guiltily all the way home.

There were three Beaumonts—Henriette, Mysilla, and Pauline. Henriette and Mysilla were twins, who had dressed alike from childhood’s hour, although Mysilla was very plain, a colorless[60] blonde, of small stature and painfully thin, while Henriette was tall, with a stately figure and a handsome dark face that would have looked well on a Roman coin. Yet Henriette was a woman of good taste, and she spent many a night trying to decide on a gown which would suit equally well Mysie’s fair head and her glossy black one. Both the black and the brown head were gray now, but they still wore frocks and hats alike. Henriette held that it was the hall-mark of a good family to clothe twins alike, and Henriette did not have her Roman features for nothing. Mysilla had always adored and obeyed Henriette. She gloried in Henriette’s haughty beauty and grace, and she was as proud of both now that Henriette was a shabby elderly woman, who had to wear dyed gowns and darned gloves, as in the days when she was the belle of the Iowa capital, and poor Jim Perley fought a duel with Captain Sayre over a misplaced dance on her ball-card. Henriette promised to marry Jim after the duel, but Jim died of pneumonia that very week. For Jim’s sake, John Perley, his brother, was good to the girls. Pauline was a baby when her father died. She never remembered the days of pomp, only the lean days of adversity. John Perley obtained a clerkship for her in a music-store.[61] Henriette gave music lessons. She was a brilliant musician, but she criticised her pupils precisely as she would have done any other equally stupid performers, and her pupils’ parents did not always love the truth. Mysilla took in plain sewing, as the phrase goes. She sometimes (since John Perley had given them a sewing-machine) made as much as four dollars a week. They invariably paid their rent in advance, and when they had not money to buy enough to eat they went hungry. They never cared to know their neighbors, and Pauline cringed as she imaged Henriette’s sarcasms had she seen her sister drinking the Armstrongs’ California port. Henriette had stood in the hall corner and waved Pauline fiercely and silently away while the unconscious Mrs. Armstrong thumped at the broken bell outside, and at last departed, remarking, “Well, they must be gone, or dead!”

Therefore rather timidly Pauline opened the door of the little room that was both parlor and dining-room. Any one could see that the room belonged to people who loved music. The old-fashioned grand-piano was under protection of busts of Bach, Beethoven, and Wagner; and Mysie’s violin stood in the corner, near a bookcase full of musical biographies. An air of exquisite[62] neatness was like an aroma of lavender in the room, and with it was fused a prim good taste, such as might properly belong to gentlewomen who had learned the household arts when the rule of three was sacred, and every large ornament must be attended by a smaller one on either side. And an observer of a gentle mind, furthermore, might have found a kind of pathos in the shabbiness of it all; for everything fine was worn and faded, and everything new was coarse. The portrait of the Lieutenant-Governor faced the door. For company it had on either side small engravings of Webster and Clay. Beneath it was placed the tea-table, ready spread. The cloth was of good quality, but thin with long service. On the table a large plate of bread held the place of importance, with two small plates on either corner, the one containing a tiny slice of suspiciously yellow butter, and the other a cone of solid jelly. Such jelly they sell at the groceries out of firkins. A glass jug of tea stood by a plated ice-water jug of a pattern highly esteemed before the war. Henriette was stirring a small lump of ice about the sides of the tea-jug. She greeted Pauline pleasantly.

“Iced tea?” said Pauline. “I thought we were to have hot tea and sausages and toast. I[63] gave Mysie twenty-five cents for them this morning.” She did not say that it was the money for more than one day’s luncheon.

“Yes, Mysie said something about it,” said Henriette, “but it didn’t seem worth while to burn up so much wood merely to heat the water for tea; and toast uses up so much butter.”

“But I gave Mysie a dollar to buy a little oil-stove that we could use in summer; and there was the sausage; I don’t mean to find fault, sister Etty, but I’m ravenously hungry.”

“Of course, child,” Henriette agreed, benignly; “you are always hungry. But I think you’ll agree I was lucky not to have bought that stove and those sausages this morning. Who do you think is coming to this town next week? Theodore Thomas, with his own orchestra! And just as I was going into that store to buy your stove—though I didn’t feel at all sure it wouldn’t explode and burn the house down—John Perley came up and gave me a ticket, an orchestra seat; and I said at once, ‘The girls must go too’; but I hadn’t but twenty-five cents, and no more coming in for a week. Then it occurred to me like a flash, there was this money you had given me; and, Paula, I made such a bargain! The man at Farrell’s, where they are selling the tickets, will get us three seats, not[64] very far back in the gallery, for my orchestra seat and the money, and we shall have enough money left to take us home in the street cars. Now do you understand?” concluded Henriette, triumphantly.

“Yes, sister Etty; it will be splendid,” responded Pauline, but with less enthusiasm than Henriette had expected.

“Aren’t you glad?” she demanded.

“Oh yes, I’m glad; but I’m so dead tired I can hardly talk,” said Pauline, as she left the room. She felt every stair as she climbed it; but her face cleared at the sight of Mysie coming through the hall.

“It’s a lovely surprise, Mysie, isn’t it?” she cried, cheerfully. She always called Mysie by her Christian name, without prefix. Henriette, although of the same age, was so much more important a person that she would have felt the unadorned name a liberty. But nobody was afraid of Mysie. Pauline wound one of her long arms about her waist and kissed her.

Mysie gave a little gasp of mingled pleasure and relief, and the burden of her thoughts slipped off in the words, “I knew you ’lotted on that oil-stove, Paula, but Etty said you would want me to go—”

“I wouldn’t go without you,” Pauline burst[65] in, vehemently, “and I’d live on bread and jelly for a week to give you that pleasure.”

“There was the sausage, too; I did feel bad about that; you ought to have good hot meals after working all day.”

“No more than you, Mysie.”

“I’m not on my feet all day. And I did think of taking some of that seventy-five cents we have saved for the curtains, but I didn’t like to spend any without consulting you.”

“It’s your own money, Mysie; but anyhow I suppose we need the curtains. Go on down; Henriette’s calling. I’ll be down directly.” But after she heard her sister’s uncertain footstep on the stair she stood frowning out of the window at the Armstrong house. “It’s hideous to think it,” she murmured, “but I don’t care—we have so much music and so little sausage! I wish I had the money for my ticket to the concert to spend on meat!”

Then, remorsefully, she went down-stairs, and after supper she played all the evening on the piano; but the airs that she chose were in a simple strain—minstrel songs of a generation ago, like “Nelly was a lady” and “Hard times come again no more,” from a battered old book of her mother’s.

“Wouldn’t you like to try a few Moody and[66] Sankeys?” Henriette jeered after a while. “Foster seems to me only one degree less maudlin and commonplace. He makes me think of tuberoses!” Pauline laughed and went to the window. The white porcupine of electric light at the corner threw out long spikes of radiance athwart the narrow sidewalk, and a man’s shadow dipped into the lighted space. The man was leaning his arms on the fence. “Foolish fellow!” Pauline laughed softly to herself. That night, shortly after she had dropped asleep, she was awakened out of a dream of staying to supper with the Armstrongs, and beholding the board loaded with broiled chickens and plum-pudding, by a clutch on her shoulder. “It was quite accidental,” she pleaded; “it really was, sister Etty!” For her dream seemed to project itself into real life, and there was Henriette, a stern figure in flowing white, bending over her.

“Wake up!” she cried. “Listen! There’s something awful happening at the Armstrongs’.”

Pauline sat up in bed as suddenly as a jack-in-the-box. Then she gave a little gasp of laughter. “They are all right,” said she; “they are playing on their organ. That’s the way they play.”

The organ ceased to moan, and Henriette returned to her couch. In ten minutes she was back again, shaking Pauline. “Wake up!” she[67] cried. “How can you sleep in such a racket? He has been murdering popular tunes by inches, and now what he is doing I don’t know, but it is awful. You know them best. Get up and call to them that we can’t sleep for the noise they make.”

“I suppose they have a right to play on their own organ.”

“They haven’t a right to make such a pandemonium anywhere. If you won’t do something, I’m going to pretend I think it’s cats, and call ‘Scat!’ and throw something at them.”

“You wouldn’t hit anything,” Pauline returned, in that sleepy tone which always rouses a wakeful sufferer’s wrath. “Better shut your window. You can’t hear nearly so well then.”

“Yes, sister, I’ll shut the window,” Mysie called from the chamber, as usual eager for peace.

“You let that window alone,” commanded Henriette, sternly. A long pause—Henriette seated in rigid agony at the foot of the bed; the Armstrongs experimenting with the Vox Humana stop. “Pauline, do you mean to say that you can sleep? Pauline! Pauline!”

“What’s the matter now?” asked Pauline.

“I am going to take my brush—no, I shall take your brush, Pauline Beaumont—and hurl it at them!”

“Oh, sister, please don’t,” begged Mysie from within, like the voices on a stage.

Henriette spoke not again; she strode out of the room, and did even as she had threatened. She flung Pauline’s brush straight at the organist sitting before the window. Whether she really meant to injure young Armstrong’s candid brow is an open question; and, judging from the result, I infer that she did not mean to do more than scare her sister; therefore she aimed afar. By consequence the missile sped straight into the centre of the window. But not through it; the window was raised, and a wire screen rattled the brush back with a shivering jar.

“What’s that? A bat?” said Armstrong, happily playing on. His father and mother were beaming upon him in deep content—his father a trifle sleepy, but resolved, the morrow being Sunday, to enjoy this musical hour to the full, his mother seated beside him and reading the numbers aloud.

“You see, Ikey,” she had explained, “that’s what makes you slow. While you’re reading the numbers, you lose ’em on the organ; and while you’re finding the numbers on the keys, you loose ’em on the paper. I’ll read them awful low, so no one would suspect, and you keep your whole mind on those keys. Now begin[69] again; I’ve got a pin to prick them—2-4-3, 1-3—no, 1-8, 1-8—it’s only one 1-8; guess we better begin again.”

So Mrs. Armstrong droned forth the numbers and Ikey hammered them on the organ, pumping with his feet, whenever he did not forget. The two boys slept peacefully through the weird clamor. The neighbors, with one exception, were apparently undisturbed. That exception, named Henriette Beaumont, heard with swelling wrath.

“I’ve thrown the brush,” said she. No response from the pillow. “Now I’m going to throw the broken-handled mug,” continued Henriette, in a tone of deadly resolve; “it’s heavy, and it may kill some one, but I can’t help it!” Still a dead silence. Crash! smash! The mug with the broken handle had sped against the weather-boarding.

“Now what was that?” cried Ike, jumping up. Before he was on his feet a broken soap-dish had followed the mug. Up flew the sash, and Ike was out of the window. “What are you doing that for? What do you mean by that?” he yelled, to which the dark and silent house opposite naturally made no reply. Ike was out in the road now, and both his parents were after him. The elder Armstrong had been[70] so suddenly wakened from a doze that he was under the impression of a fire somewhere, and let out a noble shout to that effect. Mrs. Armstrong, convinced that a dynamite bomb had missed fire, gathered her skirts tightly around her ankles—as if bombs could run under them like mice—and helped by screaming alternately “Police!” and “Murder!”

Henriette gloated silently over the confusion. It did her soul good to see Ike Armstrong running along the sidewalk after supposititious boys.

The Armstrongs did not return to the organ. Henriette heard their footsteps on the gravel, she heard the muffled sound of voices; but not again did the tortured instrument excite her nerves, and she sank into a troubled slumber. As they sat at breakfast the next morning, and Henriette was calculating the share due each cup from the half-pint of boiled milk, the broken bell-wire jangled. Pauline said she would go.

“It can’t be any one to call so early in the morning,” said Henriette; “you may go.”

“‘SOMEBODY THREW THESE THINGS AT OUR WINDOW’”