The Project Gutenberg EBook of USDA Farmers' Bulletin No. 820, by H. S. Coe

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: USDA Farmers' Bulletin No. 820

Sweet Clover: Utilization

Author: H. S. Coe

Release Date: July 28, 2020 [EBook #62782]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK USDA FARMERS' BULLETIN NO. 820 ***

Produced by Tom Cosmas from images provided by USDA through

The Internet Archive.

Assistant Agronomist, Forage-Crop Investigations

FARMERS' BULLETIN 820

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Contribution from the Bureau of Plant Industry

WM. A. TAYLOR, Chief

| Washington, D. C. | May 1917 |

SWEET CLOVER may be utilized for feeding purposes, as pasturage, hay, or ensilage. With the possible exception of alfalfa on fertile soil, sweet clover, when properly handled, will furnish as much nutritious pasturage from early spring until late fall as any other legume. It seldom causes bloat.

Stock may refuse to eat sweet clover at first, but this distaste can be overcome by keeping them on a field of young plants for a few days.

As cattle crave dry roughage when pasturing on sweet clover, they should have access to it. Straw answers this purpose very well.

An acre of sweet clover ordinarily will support 20 to 30 sholes.

On account of the succulent growth, it is often difficult, in humid climates, to cure the first crop of the second season into a good quality of hay.

When seeded without a nurse crop, one cutting of hay may be obtained the first year in the North and two or three cullings in the South. Two cuttings are often obtained in the South after grain harvest. The second year a cutting of hay and a seed crop usually are harvested.

Sweet clover should never be permitted to show flower buds before it is cut for hay. It is very important that the first crop of the second season be cut so high that a new growth will develop. When the plants have made a growth of 36 to 40 inches it may be necessary to leave the stubble 10 to 12 inches high.

In cutting the first crop of the second season it is a good plan to have extension shoe soles made for the mower, so that a high stubble may be left. In some sections of the country sweet clover as a silage plant is gaining in favor rapidly.

This crop has given excellent results as a feed for cattle and sheep. Experiments show that it compares favorably with alfalfa.

Sweet clover has proved to be a profitable soil-improving crop. The large, deep roots add much humus to the soil and improve the aeration and drainage. As a rule, the yield of crops following sweet clover is increased materially.

Being a biennial, this crop lends itself readily to short rotations.

Sweet clover is a valuable honey plant, in that in all sections of the country it secretes an abundance of nectar.

This bulletin discusses only, the utilization of sweet clover. A discussion of the growing of the crop may be found in Farmers' Bulletin 797.

[1] The growing of this crop has been discussed in a previous publication, Farmers' Bulletin 797, entitled "Sweet Clover; Growing the Crop."

| Page. | |

| General statement of the uses of sweet clover | 3 |

| Sweet clover as a pasture crop | 4 |

| Sweet clover hay | 10 |

| Sweet clover as a silage crop | 20 |

| Sweet clover as a soiling crop | 22 |

| Sweet clover as a feed | 23 |

| Sweet clover as a soil-improving crop | 28 |

| Sweet clover in rotations | 31 |

| Sweet clover as a honey plant | 32 |

The utilization of sweet clover as a feed for all classes of live stock has increased rapidly in many parts of the country, owing primarily to the excellent results obtained by many farmers who have used this plant for pasturage or hay, and also to the fact that feeding and digestion experiments conducted by agricultural experiment stations show that it is practically equal to alfalfa and red clover as a feed.

As a pasture plant, sweet clover is superior to red clover, and possibly alfalfa, as it seldom causes bloat, will grow on poor soils, and is drought resistant. The favorable results obtained from the utilization of this crop for pasturage have done much to promote its culture in many parts of the United States. On account of the succulent, somewhat stemmy growth of the first crop the second year, difficulty is often experienced in curing the hay in humid sections, as it is necessary to cut it at a time when weather conditions are likely to be unfavorable. When properly cured the hay is relished by stock.

At the present time sweet clover is used to only a limited extent for silage, but its use for this purpose should increase rapidly, as the results thus far obtained have been very satisfactory.

In addition to the value of sweet clover as a feed, it is one of the best soil-improving crops adapted to short rotations which can be grown. When cut for hay, the stubble and roots remain in the soil, and when pastured, the uneaten parts of the plants, as well as the manure made while animals are on pasture, are added to the soil and benefit the succeeding crops. In addition to humus, sweet clover, in common with all legumes, adds nitrogen to the soil. This crop is grown in many sections of the country primarily to improve soils, and « 4 » the benefits derived from it when handled in this manner have justified its use, as the yields of succeeding crops usually are increased materially.

The different species of sweet clover are excellent honey plants, as they produce nectar over a long period in all sections of the United States.

Fig. 1.—Cattle pasturing on sweet clover.

With the possible exception of alfalfa on fertile soils, no other leguminous crop will furnish as much nutritious pasturage from early spring until late fall as sweet clover when it is properly handled. Live stock which have never been fed sweet clover may refuse to eat it at first, but this distaste is easily overcome by turning them on the pasture in the spring, as soon as the plants start growth (fig. 1). Many cases are on record where stock have preferred sweet clover to other forage plants. The fact that it may be pastured earlier in the spring than many forage plants and that it thrives throughout the hot summer months makes it a valuable addition to the pastures on many farms. Sweet clover is an especially valuable forage plant for poor soils where other crops make but little growth, and it is upon such soils that thousands of acres of this crop are furnishing annually abundant pasturage for all kinds of live stock. In many portions of the Middle West, where the conditions are similar to those of southeastern Kansas, it bids fair to solve the serious pasturage problems. Native pastures which will no longer provide more than a scant living for a mature steer on 4 or 5 acres, when properly seeded to sweet clover will produce sufficient « 5 » forage to carry at least one animal to the acre throughout the season. In addition to this, a crop of hay or a seed crop may be harvested from a portion of the land when it is so fenced that the stock may be confined to certain parts of the field at specific times. Land which is too rough or too depleted for cultivation, or permanent pastures which have become thin and weedy, may be improved greatly by drilling in, after disking, a few pounds of sweet-clover seed per acre. Not only will the sweet clover add considerably to the quality and quantity of the pasturage but the growth of the grasses will be improved by the addition of large quantities of humus and nitrogen to the soil.

Sweet clover has proved to be an excellent pasture crop on many of the best farms in the North-Central States. In this part of the country it may be seeded alone and pastured from the middle or latter part of June until frost, or it may be sown with grain and pastured after harvest.

When sweet clover has been seeded two years in succession on separate fields, the field sown the first year may be pastured until the middle of June, when the stock should be turned on the spring seeding. When handled in this manner excellent pasturage is provided throughout the summer, and a hay or seed crop may be harvested from the field seeded the previous season.

Some of the best pastures in Iowa consist of a mixture of Kentucky bluegrass, timothy, and sweet clover. On a farm observed near Delmar, Iowa, stock is pastured on meadows containing this mixture from the first part of April to the middle of June. From this time until the first part of September the stock is kept on one-half to two-thirds the total pasture acreage. The remainder of the pasture land is permitted to mature a seed crop. After the seed crop is harvested the stock again is turned on this acreage, where they feed on the grasses and first-year sweet-clover plants until cold weather. The seed which shatters when the crop is cut is usually sufficient to reseed the pastures. By handling his pasture land in this manner, the owner of the farm has always had an abundance of pasture and at the same time has obtained each year a crop of 2 to 4 bushels of recleaned seed to the acre from one-third to one-half of his pasture land. This system has been in operation on one field for 20 years and not until the last two year's has bluegrass showed a tendency to crowd out the sweet clover. It is essential that sufficient stock be kept on the pastures to keep the plants eaten rather closely, so that at all times there will be an abundance of fresh shoots.

Whenever the first crop of the second year is not needed for hay or silage it can be used for no better purpose than pasturage. In fact, it is better to pasture the fields until the middle of June, as this affords one of the most economical and profitable ways of handling « 6 » the first crop. In addition to its value for pasture, grazing induces the plants to send out many young shoots close to the ground, so that when the plants are permitted to mature seed a much larger number of stalks are formed than would be the case if the first crop were cut for hay. The hay crop is likely to be cut so close to the ground that the plants will be killed, whereas but little danger of killing the plants arises from close pasturing early in the season. Excellent stands of sweet clover will produce an abundance of pasturage for two to three mature steers per acre from early spring to the middle of June.

Cattle which are pasturing on sweet clover alone crave dry feed. Straw has been found to satisfy this desire and straw or hay should be present in the meadow at all times, After stock are removed from the field it is an excellent plan to go over it with a mower, setting the cutter bar so as to leave the stubble 6 to 8 inches high. This will even up the stand, so that the plants will ripen seed at approximately the same date.

Experiments by many farmers in the Middle West show that sweet clover is an excellent pasture for dairy cattle. When cows are turned on sweet clover from grass pastures the flow of milk is increased and its quality improved. Other conditions being normal, this increase in milk production will continue throughout the summer, as the plants produce an abundance of green forage during the hot, dry months when grass pastures are unproductive. If pastures are handled properly they will carry at least one milk cow to the acre during the summer months.

In many parts of the country sweet clover has proved to be an excellent pasturage crop for hogs. When it is utilized for this purpose it usually is seeded alone and pastured for two seasons. The hogs may be turned on the field the first year as soon as the plants have made a 6-inch growth. From this time until late fall an abundance of forage is produced, as pasturing induces the plants to send out many tender, succulent branches. Pasturing the second season may begin as soon as growth starts in the spring. If the field is not closely grazed the second season it is advisable to clip it occasionally, leaving an 8-inch stubble, so as to produce a more succulent growth.

An acre of sweet-clover pasture ordinarily will support 20 to 30 shotes in addition to furnishing a tight cutting of hay (fig. 2). For the best growth of the hogs, they should be fed each day 2 pounds of grain per hundredweight of the stock. Hogs are very fond of sweet clover roots and should be ringed before being turned on the pasture. The tendency to root may generally be overcome by adding some protein to the grain ration. Meat meal serves this purpose very well.

The Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station conducted an interesting pasturing experiment with spring pigs in 1910, In this experiment, pigs weighing approximately 38 pounds each were pastured for a period of 141 days on two plats of red clover, a plat of Dwarf Essex rape, and a plat of yellow biennial sweet clover. The pigs pasturing on each plat received a ration of ear corn. The ration given to the pigs on one plat of red clover and on that of rape was supplemented with meat meal to the extent of one-tenth of the ear corn ration. The feed given to the pigs pasturing on sweet clover was supplemented with meat meal at the same rate during only the last 57 days of the test. The red clover was seeded in 1908 and reseeded in 1909, so that the plat contained a very good stand of plants at least one year old. The sweet clover was seeded in the spring of 1910, while the rape was sown on April 4, 1910, in 24-inch rows. The pigs were turned on the forage plats on June 22.

Fig. 2.—Hogs pasturing on sweet clover.

The results of this experiment, as presented in Table I, show that sweet clover carried more pigs to the acre and produced cheaper gains and a greater net profit per acre than either red clover or rape. To judge from the date of seeding of the plants tested, it was to be expected that the pigs pasturing on the sweet clover would not gain as rapidly at first as those pasturing on the other forage plants, as the growth of the sweet clover at this time was undoubtedly much less than that of the other crops. This assumption is borne out by the results given for the first 84 days of the test. During this period the pigs on the rape made a net gain of $11.55 per acre and those on the red clover $6.86 per acre more than those on the sweet clover. In these computations corn was valued at 50 cents per bushel and hogs at $6 per hundredweight. During the latter part of the experiment « 8 » there was but a scant growth of red clover on the plats, while the sweet clover produced an abundance of forage, and during this period of the experiment the pigs pasturing on sweet clover made a net gain of $10.14 per acre more than those pasturing on red clover and $17.41 per acre more than those pasturing on rape. (Table I.) The difference in net profits probably would have been greater had white sweet clover been used instead of yellow sweet clover, as it makes a larger growth and contains approximately the same ratio of food elements.

Table I.—Relative merits of Dwarf Essex rape, red clover, and yellow sweet clover when pastured by spring pigs for 141 days, June 22 to November 10, 1910.

| Forage tested, plat area, and ration. | Number of hogs. | Initial weight per hog. | Total gain, all hogs. | Average daily gain per hog. | Supplementary feed required for 100 pounds of gain. | Total cost of 100 pounds of gain.[2] | Net profit per acre.[3] | |

| Shelled corn. | Meat meal. | |||||||

| Rape (Dwarf Essex, 0.9 acre), and ear corn[4] plus one-tenth meat meal. | 18 | 37.8 | 2,801.7 | 1.10 | 292.5 | 33.99 | $3.79 | ...... |

| Reduced to acre basis. | 20 | .... | 3,113.0 | .... | ..... | ..... | ..... | $88.64 |

| Clover (medium red, 0.8 acre) and ear corn alone[4]. | 15 | 39.0 | 1,790.0 | .84 | 370.6 | None. | 3.71 | ...... |

| Reduced to acre basis. | 18.75 | .... | 2,237.5 | .... | ..... | ..... | ..... | 51.20 |

| Clover (medium red, 0.8 acre) and ear corn[4] plus one-tenth meat meal. | 15 | 39.0 | 2,394.0 | 1.13 | 299.3 | 34.77 | 3.84 | ...... |

| Reduced to acre basis. | 18.75 | .... | 2,992.5 | .... | ..... | ..... | ..... | 64.55 |

| Sweet clover[5] (yellow biennial, 0.8 acre) and ear corn[4] plus one-tenth meat meal. | 18 | 37.8 | 2,594.0 | 1.02 | 313.6 | 24.70 | 3.70 | ...... |

| Reduced to acre basis. | 22.60 | .... | 3,242.5 | .... | ..... | ..... | ..... | 74.50 |

[2] Corn valued at 50 cents per bushel, meat meal at $2.50 per hundredweight.

[3] Hogs valued at $6 per hundredweight.

[4] During the first 84 days of the test, practically two-thirds of the time, a limited ration of corn was given, while during the last 57 days the pigs received a full feed.

[5] The pigs pasturing on sweet clover received meat meal only during the last 57 days of the experiment.

An experiment reported by the New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station shows that a mixture of rape and sweet clover makes an exceptionally fine pasture for hogs. In this experiment the mixture of rape and sweet clover produced more pasturage than alfalfa and was preferred to alfalfa by the hogs. It was seeded at the rate of 6 pounds of Dwarf Essex rape and 10 pounds of sweet clover to the acre.

Sheep relish sweet clover and make rapid gains when pastured on it. Care must be taken to see that pastures are not overstocked with sheep, as they are likely to eat the plants so close to the ground as to kill them. This is especially true the first year, before the plants have formed crown buds. Yellow biennial sweet clover probably would not suffer from this cause as much as the white species, because the plants make a more prostrate growth and are not likely to be eaten so closely to the ground.

Horses and mules do well on sweet-clover pastures. On account of the high protein content sweet clover provides excellent pasturage for young stock. No cases of slobbering have been noted with horses.

Milk may be tainted occasionally when cows are pasturing on sweet clover. However, the large majority of farmers who pasture sweet clover on an extensive scale report very little or no trouble. The flavor imparted to milk at times is not disliked by all people, as some state that it is agreeable and does not harm the market value of dairy products in the least. This trouble is experienced for the most part in the early spring. The tainting of milk may be avoided by taking the cows off the pasture two hours before milking and keeping them off until after milking the following morning.

Unlike the true clovers and alfalfa, sweet clover seldom causes bloat; in fact, with the exception of the summer of 1915, only a few authentic cases of bloat have thus far been recorded in sections where large acreages are pastured with cattle and sheep. A number of cases of bloat wore reported in Iowa during the abnormally wet season of 1915. No satisfactory explanation for this comparative freedom from bloating has been offered. It is held by some that the coumarin in the plants prevents bloating, but this has not been established experimentally.

Cattle.—If the case of bloat is not extreme, it may be sufficient to drive the animals at a walk for a quarter or half an hour. In urgent cases the gas must be allowed to escape without delay, and this is best accomplished by the use of the trocar. In selecting the place for using the trocar, the highest point of the distended flank equally distant from the last rib and the point of the hip must be chosen. Here an incision about three-fourths of an inch long should be made with a knife through the skin, and then the sharp point of the trocar, being directed downward, inward, and slightly forward, is thrust into the paunch. The sheath of the trocar should be left in the paunch as long as any gas continues to issue from it. In the absence of a trocar an incision may be made with a small-bladed knife and a quill used to permit the gas to escape. Care must be taken to see that the quill does not work down out of sight into the incision.

Another remedy consists in tying a large bit, the diameter of a pitchfork handle, in the mouth, so that a piece of rubber tubing may be passed through the mouth to the first stomach to allow the gas to escape.

When the animal is not distressed and the swelling of the flank is not great, or when the most distressing condition has been removed by the use of the trocar, it is best to administer internal medicine. Two ounces of aromatic spirits of ammonia should be given every half hour in a quart of cold water, or half an ounce of chlorid of lime may be dissolved in a pint of tepid water and the dose repeated every half hour until the bloating has subsided.[6]

[6] See "Diseases of Cattle," a special report of the Bureau of Animal Industry.

For acute bloating the Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station recommends 1 quart of a 11/2 per cent solution of formalin, followed by placing a wooden block in the animal's mouth and by gentle exercise if the animal can be gotten up.

Sheep.—Gas may be removed quickly from bloated sheep by using a small trocar. The seat of the operation is on the most prominent portion of the left flank.

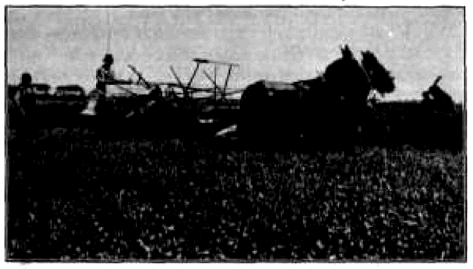

When sweet-clover hay is cut at the right time and cured properly it is eaten readily by all classes of live stock. As the hay is rich in protein, growing stock make gains on it comparable to the gains of those fed on alfalfa. The quantity and quality of the milk produced when the hay is fed to cows are approximately the same as when other legumes are used. Hay which is cut the first year is fine stemmed and leafy and resembles alfalfa in general appearance. Unless it is cut at the proper time the second year, it will be stemmy and unpalatable. Feeding experiments show that it contains practically as much digestible protein as alfalfa and more than red clover, but the hay is not as palatable as red clover or alfalfa when the plants are permitted to become coarse and woody. When sweet clover is seeded in the spring without a nurse crop in the northern and western sections of the United States, a cutting of hay may be obtained the same autumn. When it is seeded with a nurse crop in these regions, the rainfall during the late summer and early fall will largely determine whether the plants will make sufficient growth to be cut for hay. On fertile, well-limed soils in the East, in the eastern North-Central States, in Iowa, and in eastern Kansas a cutting of hay is commonly obtained after grain harvest when the rainfall is normal or above normal. In many sections of the country two, and at times three, cuttings of hay may be obtained the second year (fig. 3).

In the South two, and sometimes three, cuttings may be obtained the first year if the seeding is done without a nurse crop. When the seed is sown in the spring with oats, two cuttings may be secured « 11 » after oat harvest. Three cuttings may be obtained the second year, although it is the common practice to cut the first crop for hay and the second crop for seed.

The total yields of sweet clover per acre for the season are usually less than those of alfalfa except in the semiarid unirrigated portions of the country. Sweet clover ordinarily yields more to the acre than any of the true clovers.

Fig. 3.—Cutting sweet clover for hay in western Kansas.

When the seed is sown in the spring in the North without a nurse crop, yields of 1 to 3 tons of hay of good quality may be expected the following autumn, The Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station obtained 2,700 pounds of hay per acre in the fall from spring seeding, while the United States Department of Agriculture obtained 3,000 pounds of hay per acre in August from May seeding in Maryland. Yields of 1 to 2 tons, and occasionally 3 tons, have been obtained in Michigan, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, the Dakotas, and other States. In Illinois, Iowa, and Kansas yields of 1 to 11/2 tons are often obtained after grain harvest when weather conditions are favorable.

The first crop the second season yields 11/2 to 3 tons of hay to the acre in the northern and western sections of the United States. The second crop of the second season will yield from three-fourths to 11/2 tons to the acre, although this crop usually is cut for seed.

When sweet clover is seeded in the South without a nurse crop on fairly fertile soil that is not acid, three cuttings of hay, averaging at least a ton to the cutting, may be secured the year of seeding. When the seed is sown in the early spring on winter grain, two cuttings, « 12 » yielding at least 1 ton to the cutting, may be obtained. The first crop the second season yields on an average 11/2 to 3 tons of hay to the acre. In 1903 the Alabama Canebrake Station obtained 21/2 tons of hay after oat harvest and a total yield of 3 tons per acre from the same field in 1904.

The first season's growth of sweet clover does not usually get coarse and woody and therefore may be cut when it shows its maximum growth in the fall, In regions where more than one crop may be obtained the first season, the first crop should be cut when the plants have made about a 30-inch growth.

The proper time to cut the first crop the second season will vary considerably in different localities, depending very much upon the rainfall, the temperature, and the fertility of the soil. In no event should the plants be permitted to show flower buds or to become woody. In the semiarid sections of the country sweet clover does not grow as rapidly as in more humid regions. Neither do the plants grow as rapidly on poor soils as upon fertile soils. In the drier sections the best results usually are obtained by cutting the first crop when the plants have made a growth of 24 to 30 inches. On fertile, well-limed soils in many sections of the country a very rapid growth is made in the spring, and often the plants will not show flower buds until they are about 5 feet high. On such soils it is very essential that the first crop be cut when the plants have made no more growth than 30 to 32 inches if hay is desired which is not stemmy and if a second growth is to be expected.

It is not necessary to leave more than an ordinary stubble when cutting the sweet-clover hay crop in the fall of the year of seeding. A stubble 4 or 6 inches in height, however, will serve to hold drifting snow and undoubtedly will be of some help in protecting the plants from winter injury. While sweet clover without question is more hardy than red clover, usually more or less winterkilling occurs, and any protection which may be afforded during cold weather will be of considerable benefit.

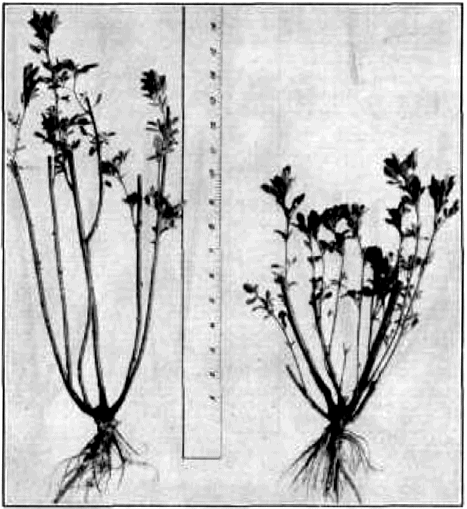

While the first crop in the second year comes from the crown buds, the new branches which produce the second crop of the second year come from the buds formed in the axils of the leaves on the lower portions of the stalks which constitute the first crop, as shown in figure 4. These branches usually commence growth when the plants are about 24 inches high. In fields where the stand is heavy and where the lower portions of the plants are densely shaded, these « 13 » shoots are soon killed from lack of necessary light. (Figs. 4 and 5.) The branches which are first to appear and which are first to be killed are those closest to the ground. It is therefore very important when cutting this crop to cut the plants high enough from the ground to leave on the stubble a sufficient number of buds and young branches to produce a second crop.

Fig. 4.—Sweet-clover plants, showing the direct relation that exists between the thickness of stand, the time of cutting, and the height at which the stubble must be cut if a second crop is to be expected. The plant at the left was cut 10 day later than the plant at the right. Note the height at which it was necessary to cut this plant so that a second crop would develop and also the scars on the stubble where young shoots had started earlier and were killed from lack of sunlight. When the stand is thin the young shoots will survive, as they did on the plant at the right, even though the field is cut at a later date.

Examination of hundreds of acres of sweet clover in different sections of the United States during the summers of 1915 and 1916 « 14 » showed that the stand on at least 50 per cent of the fields was partly or entirely killed by cutting the first crop the second season too close to the ground. A direct relation exists between the thickness of the stand, the height of the plants, and the height at which the stubble should be cut if a second crop is to be harvested. It is very essential to examine the fields carefully before mowing, so as to determine the height at which the plants should be cut in order to leave at least one healthy bud or young branch on each stub. In fact, the stand should be cut several inches above the young shoots or buds, the stubble may die back from 1 to 3 inches if the plants are cut during damp or rainy weather.

Fig. 5.—Stubble of sweet clover collected in fields where 90 per cent of the plants had been killed by cutting too closely to the ground. The heavy stands in these fields were not cut until the plants had made a growth of 36 to 40 inches. Note the scars on the stubble where young shoots started, but died from lack of light.

When fields of sweet clover contain only a medium-heavy stand and when the plants have made no more than a 30-inch growth, a 5 to 6 inch stubble usually will be sufficient to insure a second crop, but where fields contain heavy stands—15 to 25 plants to the square foot—it may be necessary to leave an 8-inch stubble. In many fields examined in northern Illinois in June, 1916, heavy stands had been permitted to make a growth of 36 to 40 inches before cutting. In a number of these fields a very large percentage of the plants were killed when an 8 to 12 inch stubble was left. (See fig. 5.) A careful examination of such fields showed that the young branches had started on the lower portions of the stalks and had died from lack of light before cutting. In semiarid regions, where the plants do not make as rapid growth as in humid sections, they may, as a rule, be clipped somewhat closer to the ground without injury.

On account of the difference in the growth that sweet clover makes on different types of soil and on account of the difference in the thickness of the stand obtained in different fields, it is impossible to give any definite rule as to the proper height to cut the first crop.

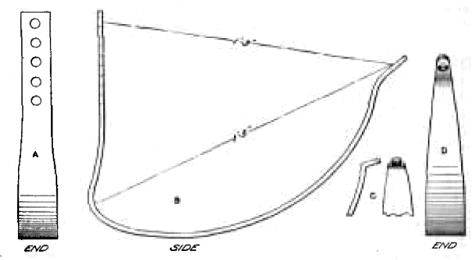

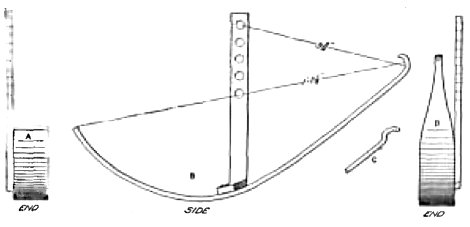

Fig. 6.—Shoe sole to be placed on the inner shoe of the mower, so that a high stubble may be left when mowing sweet clover: A, End view of the back part of the sole; B, side view of the sole, showing general shape; C, shape of the front end of the pole when it is to be used on mowers having shoes of the type used on Deering machines; D, forward end of the sole represented in B. The toward end of the sole shown in B and D should be made for machines having shoes of the type used on McCormick mowers.

It is good practice to replace the shoe soles of the mower with higher adjustable soles, so that a stubble up to 12 inches in height may be left when cutting sweet clover, Shoe soles such as are shown in figures 6 and 7 may be made on any farm provided « 16 » with a blacksmith's forge, or they can be made at any blacksmith shop at a cost which should not exceed $2.50. Preferably they should be of strap iron, about one-fourth of an inch thick and 2 inches wide; however, old pieces of iron or steel which may be found on the farm will serve the purpose.

Fig. 7.—Shoe sole to be Used on the outer shoe of the mower, so that a high stubble may be left when cutting sweet clover; A, End view of the back part of the sole; B, side view of the sole, showing general shape; C, forward end of the sole to be used on certain Deering machines; D, end view of the front part of sole shown in B.

Then these soles are to be placed on machines that have shoes of the type used on the Deering mower, the forward 8 inches of the sole for the inner shoe should be tapered gradually to a blunt point and bent in such a manner that it will hook into the slot in the shoe. (Fig. 6, C.) When the soles are to be placed on mowers having shoes of the type used on McCormick machines, the forward 8 inches of the sole for the inner shoe should be tapered gradually to about 1 inch in width, bent forward so that it will fit against that portion of the shoe where it is to be bolted, and have a hole of the proper size bored for the bolt three-fourths of an inch from the end. (Fig.6, B and D.) The bottom of the sole should be rounded, so as to run smoothly on the ground when the cutter bar is raised to cut at different heights. The back portion of the sole should be upright and should have holes bored in it, so that it may be set for the cutter bar to rest at different heights from the ground. Preferably the lower hole of the upright should be located so that when the bolt in the shoe is run through it the cutter bar will be 6 inches from the ground. It should be long enough to permit four or five holes, 1 inch apart, to be bored above the lower one. (Fig. 6, A.)

With some makes of machines it is not advisable to raise the cutter bar higher than 10 inches from the ground, but when this is true the cutter bar may be tipped upward, so that a 12-inch stubble is left.

The forward end of the shoe sole to be used on the outer shoe should be tapered gradually to 1 inch from the end. The forward inch should be one-fourth of an inch in width and bent slightly upward and inward, so that a hook will be formed to fit into the slot in the front end of the shoe. (Fig. 7, B.) The rest of the sole should curved, so that it will run smoothly on the ground when the cutter bar is set to cut at different heights. The upright which is bolted to the sole should preferably be made of three-eighths by 1 inch material and should have six holes, 1 inch apart, bored in it, so that the outer end of the cutter bar may be raised to the same height as the inner end. On practically all standard makes of mowers the outer shoe sole hooks into the shoe instead of bolting to it, as is the case with the inner sole on some machines. A wheel is used in place of a shoe sole on the outer end of the cutter bar on some machines. When this is the case, the upright to which this wheel is attached should be lengthened. On other machines the forward end of the sole hooks into a slot in the shoe in the same manner as the inner sole. In this event the front end of the sole should be bent slightly upward and outward. (Fig. 7, C.)

Before shoe soles are made for any mower a careful examination should be made of the shoes to determine the exact size required and the manner in which they should be attached to the forward ends of the shoes.

One of the greatest difficulties in curing sweet clover is the fact that the plants usually are ready to be cut for hay at a time of the year when weather conditions are likely to be unfavorable for haymaking. Little trouble is experienced in curing this crop in the drier sections of the country where the methods used for alfalfa are employed. The curing of sweet clover is more difficult than the curing of either red clover or alfalfa, as the leaves are very apt to shatter before the stems are cured. Every possible means should be employed to save the leaves, as these constitute the best part of the hay. (See Table II.)

Table II.—Average analyses of the leaves of four samples of well-cured white sweet-clover hay.

[Analyses made by the Bureau of Chemistry.]

| Samples. | Constituents (per cent). | |||||

| Moisture. | Ash. | Ether extract. | Protein. | Crude fiber. | Nitrogen-free extract. |

|

| Leaves. | 8.70 | 10.92 | 3.09 | 28.20 | 9.28 | 39.78 |

| Stems. | 8.70 | 8.08 | .70 | 10.16 | 39.45 | 33.06 |

The hay collected for the above analyses represented the first cutting the second season. The plants had made a 30 to 36 inch growth at the time of cutting. It will be seen that the protein content of the leaves is almost three times as great as that of the stems.

In the drier sections of the country or when the first crop of the year of seeding is cut for hay in the North-Central States the mower may be started in the morning as soon as the dew is off. The hay should remain in the swath until the following day, or until it is well wilted, when it should be raked into small windrows. After remaining in the windrows for a day it may be placed in small cocks to cure. Cocks made from hay which has dried to this stage will not shed water well and therefore should be covered if it is likely to rain. It is important that the cocks be made small enough to be thrown on the rack entire, as many leaves will be lost if it is necessary to tear them apart.

Fig. 8.—Sweat clover curing in the cock.

When sweet clover is permitted to dry in the swath, a large percentage of the leaves will be lost in windrowing and loading unless handled with the utmost care. Hay in this condition should never be raked while perfectly dry and brittle, but should be raked into the windrow in the early morning or in the evening, when it is slightly damp from dew. It may then be hauled to the barn or stack after remaining in the windrow for a day.

One of the most successful methods for handling sweet-clover hay, especially in regions where rains are likely to occur at haying time, is to permit the plants to remain in the swath until they are well wilted or just before the leaves begin to cure. The hay should then be raked into windrows and cocked at once (fig. 8). The cocks « 19 » should be made as high and as narrow as possible, as this will permit better ventilation. In curing, the cocks will shrink from one-third to one-half of their original size. It may take from 10 days to 2 weeks to cure sweet clover by this method, but when well cured all the leaves will be intact and the hay will have an excellent color and aroma. When sweet clover is cocked at this time the leaves will cure flat and in such a manner that the cocks will readily shed water during heavy rains (fig. 9).

Fig. 9.—A cock of sweet-clover hay which has cured

in excellent condition and retained

all of its leaves.

When sweet-clover hay is to be stacked it is highly desirable that some sort of foundation be made for the stack, so as to prevent the loss of the hay which otherwise would be on the ground. Several feet of straw or grass are often used for this purpose, but still better is a foundation of rails, posts, or boards placed in such a manner that air may circulate under the stack.

A cover should be provided for the stacks, either in the form of a roof, a canvas, or long green grass. If none of these means is practicable a topping of perfectly green sweet clover will cure with the leaves flat and will turn water nicely.

It is well known that hay made from either red clover or alfalfa will often undergo spontaneous combustion if put into the barn « 20 » with too much external moisture upon it. No instances of spontaneous combustion in sweet-clover hay have been noted, but this may be due to the fact that comparatively little sweet-clover hay is stored in barns. The same precautions, therefore, should be taken with sweet-clover hay as with red clover or alfalfa.

In some sections of the country sweet clover is gaining in favor as a silage crop, either alone or in mixtures with other plants. The silage made from this plant will keep better than that made from most legumes, as it does not become slimy, as is so often the case with red clover or alfalfa silage. It produces a palatable feed, which should contain more protein than well-matured corn silage.

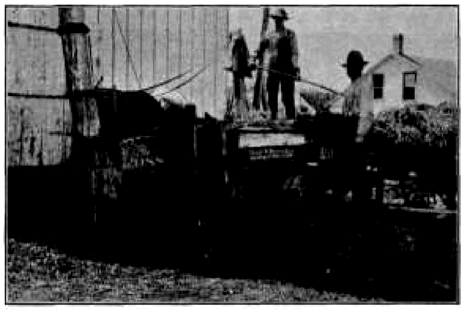

Fig. 10.—Filling the silo with sweet clover.

When sweet clover makes sufficient growth after grain harvest, or when seeded alone, it is not necessary to cut it for silage until fall. At this time it may be run into the silo alone or in mixture with corn. Excellent results have been obtained by placing alternate loads of corn and sweet clover in the silo. (Fig. 10.)

When the first crop the second season is not needed for pasturage, ensiling may prove to be the most economical and profitable way of handling it, as it is necessary to cut this crop for hay at a time of the year when the weather conditions in humid regions are very likely to be unfavorable for haymaking. The large percentage of leaves which usually are lost from shattering when harvesting the hay will be saved when the crop is run into the silo.

The first crop the second season will produce approximately two-thirds as much silage to the acre as corn when it is cut at the time it should be cut for hay. The second crop may then be harvested for seed. When sweet clover is handled in this manner, approximately two-thirds of the total corn acreage which would be cut for silage may be permitted to mature, as the first crop of sweet clover will replace the corn silage, while the seed crop ordinarily will bring as much per acre as the corn. In addition to this, the roots and stubble will add large quantities of vegetable matter to the soil.

Some farmers do not cut sweet clover for silage until it is in full bloom. When this is done, 10 to 12 tons of silage will be obtained per acre, but the plants will be killed by the mowing.

Fig. 11.—Cutting sweet clover with a grain binder for silage.

When the green plants are ensiled, the crop preferably should be cut with a grain binder. (See illustration on title-page and fig. 11.) This will solve the difficulty of cutting a high stubble and will at the same time bind the plants so that they may be run through the silage cutter without difficulty. Green plants, and especially the first crop of the second season, contain too much moisture to be run into the silo immediately after cutting. In some cases quantities of juice have been pressed out of the bottom of the silo, and as a result the silage settled considerably. Analyses of the juice from one silo showed that it contained 0.23 per cent protein and 2 per cent carbohydrates. This loss of juice may be overcome by permitting the bundles to remain in the field just as they come from the binder until the plants are wilted thoroughly. Straw or corn stover may be placed in the bottom of the silo to absorb some of the juice. If the « 22 » plants contain too much moisture it may be a good plan to mix some corn stover with the sweet clover as it is run into the silo.

Several silos in Illinois have been filled with sweet-clover straw. When this is done it is necessary to add sufficient water to moisten the dry stems. These stems become soft in a short time and ensile in good condition. When the seed crop is thrashed with either a grain separator or a clover huller the stems are broken and crushed sufficiently to render it unnecessary to run them through a silage cutter. Care must be taken when ensiling the straw to add sufficient water, if molding is to be avoided. It will probably be necessary to add water at the blower and also at the top of the silo. It is essential to tramp the straw thoroughly, so as to exclude as much air as possible. After the silo is filled it should be covered with a layer of green plants and thoroughly soaked with water.

Table III gives analyses of several sample of sweet-clover silage as compared to corn silage.

Table III.—Composition of sweet-clover silage and well-matured corn silage.

| Kind of silage. | Number of analyses. | Constituents (per cent). | |||||

| Water. | Ash. | Crude Protein. | Carbohydrates. | Fat. | |||

| Fiber. | Nitrogen- free extract. |

||||||

| White sweet clover; | |||||||

| First year's growth[7] | 1 | 73.7 | 1.73 | 3.17 | 20.8 | 0.65 | |

| First crop, second season[8] | 1 | 73.7 | 2.57 | 2.05 | 8.06 | 12.32 | 1.27 |

| Straw[8] | 3 | 73.7 | 1.19 | 2.70 | 13.59 | 8.33 | .50 |

| Corn, well matured[9] | 121 | 73.7 | 1.70 | 2.10 | 6.30 | 15.40 | .80 |

[7] Analysed by the Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station.

[8] Analysed by the Bureau of Chemistry.

[9] Analyses compiled by Henry and Morrison.

As shown in Table III the analyses of the first and second years' growth of sweet clover compare favorably in food elements with corn silage. It is to be expected that the silage made from the sweet clover straw would contain less protein and carbohydrates than that made from the entire plants, as most of the leaves shatter from sweet clover before the seed crop is cut. Considerable protein and carbohydrates were lost from the silage made from the first crop the second season, as the plants were run into the silo as soon as they were cut. Much juice was pressed from the bottom of this silo. An analysis of this juice is given on page 21.

As a soiling crop sweet clover has been used to only a very limited extent. The amperage yields of green matter vary from 6 to 15 tons per acre, The season for soiling may commence when the plants « 23 » are 12 to 15 inches high and continue until flower buds appear. An area of such a size that the plants may be cut every four or five weeks should be selected. The plants should not be cut closer to the ground than 4 inches during the first part of the season and 9 to 12 inches during the latter part of the season. On account of the high protein content and the large amount of forage produced on a relatively small area, sweet clover may profitably be fed in this manner when more desirable soiling crops are not to be had.

The woody growth of sweet clover as it reaches maturity and the bitter taste due to coumarin have been the principal causes for live stock refusing to eat it at first. On this account many farmers have assumed it to be worthless as a feed. It is a fact that stock seldom eat the hard, woody stems of mature plants, but it is true also that stock eat sparingly of the coarse, fibrous growth of such legumes as red or mammoth clover when they have been permitted to mature and have lost much of their palatability. All kinds of stock will eat green sweet clover before it becomes woody, or hay which has been cut at the proper time and well cured, after they have become accustomed to it. Many cases are on record in which cattle have refused alfalfa or red clover when sweet clover was accessible. Milch cows have been known to refuse a ration of alfalfa hay when given to them for the first time. Western range cattle which have never been fed corn very often refuse to eat corn fodder, or even corn, for a short time, and instances have come under observation in which they ate the dried husks and left the corn uneaten. When these cattle were turned on green grass the following spring they browsed on the dead grass of the preceding season's growth, which, presumably more closely resembled the grass to which they were accustomed. Such preliminary observations should never be taken as final, even when they represent the results of careful investigators. When cowpeas were first introduced into certain sections of this country much trouble was experienced in getting stock to eat the vines, either when cured into hay or made into ensilage. This difficulty, however, was soon overcome.

It is very true that stock which have never been pastured on sweet clover or fed on the hay must become accustomed to it before they will eat it, but the fact that sweet clover is now being fed to stock in nearly every State indicates that the distaste for it can be overcome easily and successfully. As sweet clover usually starts growth earlier in the spring than other forage plants and as the early growth presumably contains less coumarin than older plants, « 24 » stock seldom refuse to eat it at this time. Properly cured hay is seldom refused by stock, especially if it is sprinkled with salt water when the animals are salt hungry.

Sweet clover, like most legumes, contains a relatively high percentage of protein, thus making it a source of that valuable constituent of feeds needed for growing stock and for the production of milk. Table IV shows the relative composition and digestibility of sweet clover as compared to some other feeds.

Table IV.—Composition and digestibility of sweet clover compared with that of other forage crops.

| Kinds of forage. | Number of analyses. |

Constituents (per cent). | |||||

| Water. | Ash. | Crude Protein. |

Carbohydrates. | Fat. | |||

| Fiber. | Nitrogen- free extract. |

||||||

| Green crop: | |||||||

| Sweet clover[10] | 18 | 75.6 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 7.0 | 10.2 | 0.7 |

| Alfalfa[10] | 143 | 74.7 | 2.4 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 10.4 | 1.0 |

| Red Clover[10] | 85 | 73.8 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 7.3 | 11.7 | 1.0 |

| Hay (moisture-free basis): | |||||||

| White sweet clover[11] | 37 | .... | 8.2 | 17.6 | 28.2 | 43.0 | 3.0 |

| Yellow sweet clover[11] | 3 | .... | 6.4 | 15.8 | 35.6 | 39.0 | 2.6 |

| Alfalfa[11] | 211 | .... | 9.6 | 17.4 | 29.8 | 40.3 | 2.9 |

| Red clover[11] | 99 | .... | 7.0 | 15.6 | 27.7 | 44.9 | 3.9 |

| Timothy[11] | 194 | .... | 6.2 | 8.2 | 32.5 | 49.9 | 3.2 |

| Kinds of forage. | Dry matter in 100 pounds. | Digestible nutrients in 100 pounds of air-dried hay. |

Nutritive ratio.[13] | |||

| Protein. | Carbo- hydrates. |

Fat. | Dry matter. | |||

| White sweet-clover hay | 92.2 | 11.88 | 36.68 | 0.49 | 56.1 | 1:3.2 |

| Pea hay | 93.1 | 11.24 | 48.55 | .71 | 62.5 | 1:4.5 |

| Alfalfa hay (second cutting) | 92.2 | 11.73 | 42.38 | .72 | 60.90 | 1:3.8 |

[10] Analyses taken from Henry and Morrison's "Foods and Feeding."

[11] Analyses compiled by the Bureau of Chemistry.

[12] Experiments conducted by the Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station.

[13] The nutritive ratio is the ratio which exists between the digestible crude protein and the combined digestible carbohydrates and fat.

Table IV shows that the percentage composition of both green and cured sweet clover compares favorably with that of alfalfa and red clover.

Perhaps the most interesting point shown in this table is that the fiber content of white sweet clover, whether green or cured into hay, is no greater than that of alfalfa. It is understood, however, that the plants collected for these analyses were taken when they were at« 25 » the proper stage for curing into hay. Table IV also shows that the digestible nutrients of sweet clover when fed to sheep compare favorably with alfalfa. It was stated that the sweet-clover hay used for this experiment was stemmy and that it had not been cut until it had become woody. The pea hay had passed the best stage for cutting when it was harvested, while the alfalfa hay was in excellent condition.

In a feeding experiment with sheep conducted by two students at the Iowa State College it was found that the protein digested in sweet-clover feed alone was 69 per cent and that the addition of corn to the hay ration increased the digestibility of sweet clover to 82 per cent. Alfalfa and red clover showed similar increases of the digestibility of the protein content when corn was added to the ration. The percentage of digestibility figured for the protein in the corn was the average of a number of digestion experiments. The probability is that the digestibility of the corn was also increased by the presence of the hay in the ration, so that not all the increase in the digestibility should be credited to the hay constituents of the different rations.

Few agricultural experiment stations have carried on definite feeding experiments to determine the value of sweet clover compared with other feeds.

The South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station reported an experiment in which lambs were fed on sweet-clover hay in comparison with alfalfa, pea-vine, and prairie hay. In this experiment the lambs made a better gain at a less cost when fed sweet-clover hay than when fed pea-vine hay, but not as large a gain as when fed alfalfa hay. The results of this experiment are shown in Table V.

Table V.—Feeding experiment with lambs in South Dakota, showing the comparative value of different kinds of hay as roughage.

[Grain ration consists of oats and corn in all cases; roughage varies.]

| Roughage fed. | Number of lambs. | Duration of test. | Average weight. | Required for 1 pound of gain. | Average daily gain per head. | ||

| At begin- ning. |

At end. | Grain. | Hay. | ||||

| Days. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | ||

| Prairie hay | 16 | 67 | 83.6 | 107.9 | 5.09 | 2.35 | 0.36 |

| Pea-vine hay | 10 | 67 | 83.6 | 107.3 | 5.40 | 3.15 | .35 |

| Alfalfa hay | 5 | 67 | 81.4 | 119.4 | 3.36 | 3.02 | .56 |

| Sweet-clover hay | 10 | 67 | 84.7 | 113.6 | 4.42 | 3.19 | .43 |

The Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Station also performed an, interesting experiment with lambs. A number of pens of 10 to 40 lambs each were fed different mixtures of feeds for 14 weeks. Those « 26 » receiving sweet-clover hay, corn, and a small amount of oil meal made an average gain of 30.7 pounds per head, as compared with 20.3 pounds for those receiving native-grass hay, oats, and oil meal. Those receiving alfalfa hay and corn made a gain of more than 34 pounds per head. The results obtained with four pens of lambs in this experiment are given in Table VI.

Table VI.—Results of feeding tests of lambs in Wyoming covering 14 weeks.

| Ration. | Number of lambs. | Average gain per head. | Required for 100 pounds of gain. | |||||

| Sweet-clover hay. | Native hay. | Alfalfa hay. | Corn. | Oats. | Oil meal. | |||

| Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | ||

| Sweet-clover hay, corn, and oil meal (old process) | 10 | 30.7 | 637.5 | ..... | ..... | 293.2 | ..... | 20.5 |

| Native-grass hay, oats, and oil meal (old process) | 40 | 20.3 | ..... | 606.7 | ..... | ..... | 460.5 | 25.0 |

| Alfalfa hay and corn | 10 | 34.4 | ..... | ..... | 557.5 | 261.6 | ..... | ..... |

| Do | 40 | 34.3 | ..... | ..... | 557.3 | 286.5 | ..... | ..... |

The sweet-clover hay used in this experiment was described as stemmy and more than a year old; yet it was eaten up clean by the lambs.

The South Dakota Agricultural Experiment Station conducted an experiment in which steers were fed corn silage and various kinds of hay, including sweet clover. The steers which were fed corn silage and sweet-clover hay made an average daily gain of 2.45 pounds, at a cost of $4.34 per hundred pounds of gain, whereas the steers which were fed corn silage and red-clover hay made an average daily gain of 2.29 pounds, at a cost of $4.55 per hundred. The steers that were fed corn silage and alfalfa hay made an average daily gain of 2.49 pounds, at a cost of $4.30 per hundred. In computing the cost of the gains, corn silage was valued at $3 per ton, alfalfa, red-clover, and sweet-clover hay at $10 per ton, and prairie hay at $6 per ton. The results of this experiment, as given in Table VII, show that sweet-clover hay is practically equal to red-clover and alfalfa and greatly superior to prairie hay for roughage for steers.

Table VII.—Feeding experiments with steers in South Dakota, showing the value of sweet-clover hay as compared with some other kinds of hay.

[Corn silage fed in all cases; kind of hay varies.]

| Roughage. | Number of steers. | Duration of test. | Average weight. | Average daily gain. | Feed per pound of gain. | Cost per 100 pounds of gain. | ||

| At begin- ning. |

At end. | Silage. | Hay. | |||||

| Days. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | Pounds. | |||

| Red-clover hay | 4 | 91 | 775 | 983 | 2.29 | 25 | 1.5 | $4.55 |

| Sweet-clover hay | 4 | 91 | 774 | 997 | 2.45 | 23 | 1.5 | 4.34 |

| Alfalfa | 4 | 91 | 775 | 1,005 | 2.49 | 23 | 1.6 | 4.30 |

| Prairie hay | 4 | 91 | 769 | 951 | 2.01 | 29 | 1.5 | 4.79 |

The results of these various experiments are being duplicated every year by many feeders. Each year in the Middle West and Northwest many cattle that bring high prices are being fed with no other roughage than sweet-clover hay. Steers which have been pastured entirely on sweet clover have brought in the Chicago market $1 per hundredweight more than ordinary grass-pastured stock marketed from the same locality and at the same time.

Excellent results were obtained in Lee County, Ill., from feeding steers sweet-clover silage made from plants which had matured a seed crop. For this experiment 91 head of steers 2 and 3 years old, averaging 1,008 pounds per head, were purchased at the Kansas City stock yards on November 16, 1915, at a cost of $6.30 per hundred. These steers were shipped to a farm at Steward and immediately turned on 120 acres of cornstalks. They were fed nothing in addition to the cornstalks until January 14, 1916, when they were put into the feed lot. While they were not weighed when turned into the feed lot, the owner of the steers stated that in his estimation they had gained but little, if any. During the 60 days these steers were in the feed lot they were fed 25 bushels of snapped corn twice a day and as much sweet-clover silage as they would eat. These animals had access to sweet-clover straw during the first part of the feeding period, but after this was consumed they had only oat straw as roughage. At the end of the feeding period they were sold on the Chicago market at the average price of $8.25 per hundred, netting approximately $30 per head. The average weight of these steers in the Chicago yards was 1,177 pounds, 169 pounds more than when purchased in Kansas City.

A most remarkable feature of this experiment is the fact that the steers were fed almost entirely material which would have been considered of little value by the average farmer. The corn which was fed tested 44 per cent moisture at the Rochelle, Ill., elevator, and 20 cents per bushel was the best price offered for it.

Presumably on account of wet weather during the fall of 1915, the sweet-clover seed crop was a failure in that section; in fact, the crop had been cut for seed and part had been thrashed before it was decided that the seed yield was not sufficient to pay for the thrashing. The remainder of the crop was then run into the silo and fed to the steers. The leaves fall and the stems of this plant become hard and woody as the seed matures. The crop therefore would have been worthless for feed had it not been placed in the silo. As a rule, stock readily eat sweet-clover straw when the stems are broken and crushed by the hulling machines. The sweet-clover straw which was used as roughage during the first part of the feeding period was from that part of the seed crop which had been thrashed.

An interesting feeding experiment was conducted on a farm at Rochelle, Ill. On September 7, 1913, 29 head of 2-year-old steers, « 28 » averaging 836 pounds, were turned on 40 acres of sweet clover which had been seeded that spring with barley. These animals were pastured on the sweet clover until November 1 without additional feed. During this time they made exceptionally large gains. From November 1 to December 11, 28 head of these steers had access to an 80-acre field of cornstalks. On December 11 they were put into the feed lot. During the time these steers were on the cornstalks they barely held their gain, but during the first 30 days they were in the feed lot they made an average daily gain of almost 3 pounds. In this period they received 215 bushels of corn-and-cob meal and 163/4 tons of silage made from the first-year growth of sweet clover. During the next 30 days they received 388 bushels of corn-and-cob meal and much less sweet-clover, silage. During this time they made an average daily gain of 2 pounds. When the corn-and-cob meal ration was increased the steers ate less silage. These cattle dressed 551/8 per cent at a Chicago packing house.

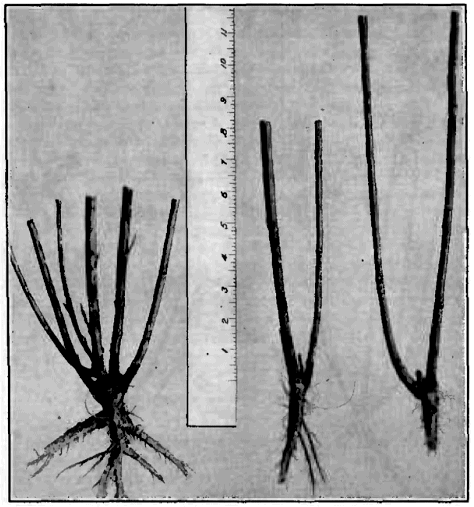

Unlike many legumes, sweet clover will make a good growth on soils too depleted in humus for profitable crop production. In addition to its ability to grow and to produce a considerable quantity of forage on such soils, it will add much humus to them. The extensive root systems do much toward breaking up the subsoil, thereby providing better aeration and drainage. The effect of the large, deep roots in opening up the subsoil and providing better drainage is often very noticeable in the spring, as the land upon which sweet clover has grown for several years will be in a condition to plow earlier than the adjacent fields where it has not been grown. The roots are often one-eighth of an inch in diameter at a depth of 3 feet, and they decay in five to eight weeks after the plants die. (Figs. 12 and 13.) The holes made by the roots are left partly filled with a fibrous substance which permits rapid drainage. Sandy soils are benefited materially by the addition of humus and nitrogen, while hardpan often is broken up so completely that alfalfa or other crops will readily grow on the land. The roots add much organic matter to the layers of soil below the usual depth of plowing, while those in the surface soil, together with the stubble and stems, when the crop is plowed under, add more humus than possibly any other legume which may be grown in short rotations. Not only does this crop add organic matter to the soil, but in common with other legumes it has the power of fixing atmospheric nitrogen by means of the nitrogen-gathering bacteria in the nodules on the roots.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12.—A portion of a root of sweet clover, collected 30 days after the seed crop had been cut. The cortex was so decayed that it remained in the ground when the root was removed. Note that the pith has largely disappeared and that the half-rotten central cylinder is allthat remains. |

Fig. 13.—The same root shown in figure 12 after being crushed between the thumb and forefinger. Illustrating how rapidly sweet-clover roots decay after the plants die. The holes left in the ground by the rapid decay of the roots facilitate drainage. |

The ability of sweet clover to reclaim abandoned, run-down land has been demonstrated in northern Kentucky and in Alabama. In these regions many farms were so depleted in nitrogen and humus by continuous cropping with nonleguminous crops that profitable yields could be obtained no longer, Through the use of this crop many of these farms have been brought back to a fair state of fertility. Tests at the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station show that the increased yield of corn following sweet clover which had occupied the land for two years was 63/4 bushels per acre. The cotton grown on the land the second year showed an increase of 56 pounds per acre. The combined value of the increased yields of corn and cotton for the two years was estimated at $9.75. The total yield of hay for the two preceding years was 6.8 tons per acre. In another experiment at this station cotton was planted on land that had grown sweet clover the two previous years and on land that had received an application of 18 tons of stable manure per acre. The sweet-clover plat produced 280 pounds of seed cotton the first year and 120 pounds of seed cotton the second year more than the plat which received the heavy application of manure.

Land on which sweet clover had been grown for four years at the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station yielded 26.9 bushels of wheat per acre as compared with 18.6 bushels on the check plat. Sweet clover was seeded at the Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station in the spring of 1912. One cutting of hay was removed that year and the following spring the field was plowed and planted to corn. The corn yielded 58.8 bushels per acre as compared with 41.1 bushels per acre for an adjoining plat where rye was turned under. A number of tests have been conducted in southeastern Kansas which show clearly the value of sweet clover as a soil-improving crop for that section. The yield of wheat has been increased as much as 7 bushels per acre and that of corn as much as 22 bushels per acre by plowing under the second-year growth of clover.

Annual yellow sweet clover is rapidly gaining in favor as a green-manure crop for orchards in the Southwest. In Arizona two plats seeded in October and plowed under in April yielded, respectively, 16 and 17 tons of green matter to the acre. At the Arizona Agricultural Experiment Station annual yellow sweet clover, lupines, and alfalfa were tested as green-manure crops for orchards. In this experiment the sweet clover clearly showed its superiority to lupines or alfalfa for this purpose, as it yielded from 21 to 26 tons of green matter per acre, whereas the highest yield for the lupines was 10 tons and for the alfalfa 15 tons per acre.

The use of annual sweet clover as a green-manure crop in southern California has increased very rapidly in recent years, and this increased use apparently has been justified by the results obtained with it. One of the most interesting green-manure tests thus far noted was conducted at the California Citrus Experiment Station. In this experiment nine legume plats and eight nonlegume plats « 31 » alternated with each other. The 4-year average weight of green matter produced on the sweet-clover plat was 143/4 tons per acre, whereas the 5-year average weight of green matter produced by common vetch and Canada field peas was 12 tons and 9 tons, respectively, per acre. On one series of these plats corn was planted in rotation with the clover. The average yield of shelled corn for four years was 46 bushels to the acre on the sweet-clover plat, as compared with 35 bushels to the acre on the common-vetch plat and 40 bushels per acre on the field-pea plat. One barley plat receiving each year an application of 1,080 pounds of nitrate of soda gave an average yield of 41 bushels per acre. The 2-year average yield of potatoes following sweet clover was 252 bushels per acre, as compared with 171 bushels following common vetch and 234 bushels following field peas. Sweet clover has proved to be an excellent plant to grow in rotation with sugar beets, as the 2-year average for the beets following it was 19.8 tons per acre, as compared with 15.3 tons following common vetch, and 17.6 tons following field peas.

Annual yellow sweet clover makes a profitable growth only in the South and Southwest and therefore should not be planted in any other section of the country.

In those sections of the United States where the soils are low in humus it is to be strongly recommended that sweet clover be grown for green manure. This method is being practiced in some sections of the country with excellent results.

It should be remembered that sweet clover will not make a satisfactory growth on acid soils and that it is very essential to provide inoculation if the soil is not inoculated already.

As sweet clover is a biennial plant, it lends itself readily to short rotations. It may be seeded in the spring on winter grain or with spring grain, the same as red clover. It will produce at least as much pasturage the following fall as red clover, and in some parts of the country a cutting of hay may be obtained after the grain harvest. The following year the plants will produce two cuttings of hay or one cutting of hay and a seed crop. In some sections of the United States this plant is replacing red clover in rotations, as it will succeed on poorer soils than red clover and will add much more humus to the soil. It will withstand drought better than either red clover or alfalfa, and on this account its use in rotations may be extended into drier sections. As a rule the beneficial effect of sweet clover on the subsequent crops is more marked than that of other legumes. This is especially true with corn, and whenever possible corn should follow sweet clover in rotations. Root crops also are benefited by its use in rotations, as the large deep roots of sweet clover open up the soil.

A number of the leading honey plants fail to secrete nectar in part of the territory in which they are found, but white sweet clover ranks as a valuable source of nectar wherever found in sufficient quantity in the United States. The period of nectar secretion usually follows that of white and alsike clovers in the Northern States, and consequently comes at a time when the colonies are strong enough to get the full benefit of the secretion. The honey from white sweet clover is light in color, with a slight green tint, the flavor being mild and suggestive of vanilla. The characteristic flavor and color of the honey seem to be less marked during a rapid secretion of nectar, In the irrigated portions of the West honey from white sweet clover is often mixed with that from alfalfa.

Beekeepers have long recognized the value of sweet clover as a source of nectar, and for years tons of seed have been sold annually by dealers in beekeepers' supplies. It has never been found profitable to cultivate any plant solely for nectar, and those beekeepers who were primarily interested in the plant for bee forage have scattered the seed chiefly in waste places and along railroad embankments and roadsides. A number of beekeepers who were also engaged in general farming have for years utilized the plant for forage, and they were among the earliest to grow the plant for seed, so as to be able to supply their fellow beekeepers. Sweet clover to-day is almost the only plant which beekeepers seek to increase in waste lands in their localities.

The yield of nectar from sweet clover is heavy, and a number of beekeepers now market this honey in carload lots. Sweet clover is utilized for honey especially in Kentucky, in Iowa, and in Colorado and adjacent States. In Alabama and Mississippi a number of beekeepers are harvesting large crops chiefly from this source. The color and flavor make this plant suitable for either comb or extracted honey.

Yellow sweet clover is perhaps as valuable for nectar as white sweet clover, but beekeepers have paid less attention to it. This is probably due to the fact that the blooming period of the yellow species often coincides with that of white and alsike clover, making it less valuable to the beekeeper. In sections where the quantity of white and alsike clover is limited and it is desired to plant sweet clover for bee pasturage, a mixture of the white and yellow species is recommended, as the yellow species will bloom from 10 to 14 days earlier than the white.

Wherever any of the species of sweet clover are cultivated, either for forage or for seed, beekeeping is to be recommended as a valuable source of additional income, and such locations are especially suitable for extensive commercial beekeeping.

Transcriber Note

Minor typos may have been corrected. Illustrations may have been moved to avoid splitting paragraphs.

End of Project Gutenberg's USDA Farmers' Bulletin No. 820, by H. S. Coe

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK USDA FARMERS' BULLETIN NO. 820 ***

***** This file should be named 62782-h.htm or 62782-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/2/7/8/62782/

Produced by Tom Cosmas from images provided by USDA through

The Internet Archive.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this