The Project Gutenberg EBook of Seeing Lincoln, by Anne Longman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Seeing Lincoln Author: Anne Longman Release Date: April 8, 2020 [EBook #61787] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SEEING LINCOLN *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Kenneth R. Black and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Presented by

Gold & Co.

LINCOLN, NEBR.

Written for The Nebraska State Journal

By Anne Longman

Come with us, all you who are new to the city or you who bid fair to live and die in Lincoln without ever having seen her various faces. We’ll teach you in—well, we don’t know how many lessons—something about the city in which you are living.

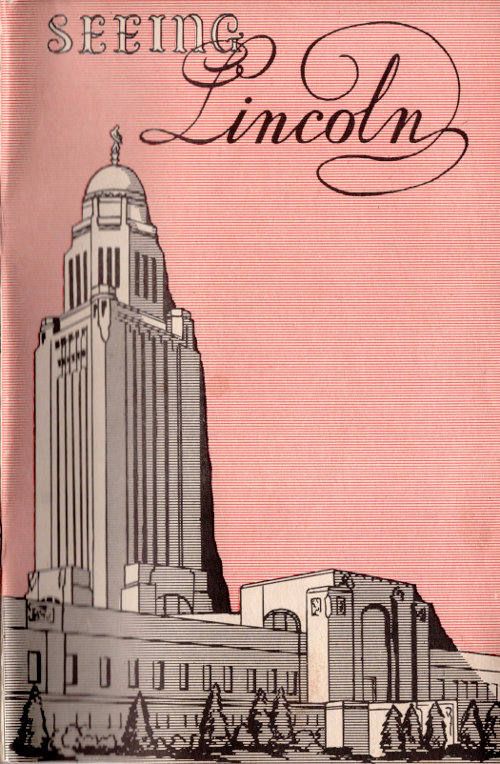

Maybe we should begin with the capitol, known over the world for its beauty. But we think we’ll start with that handy starting and stopping place, O street. Lincoln is often described as an overgrown country town, O its Main street. But even New York has its lapses into the primitive, and who doesn’t like, in medium doses, the simplicity and the friendliness that spell country town.

When Lincoln was only a handful of blocks flung down on the prairie for hasty habitation by early salt seekers, restless young Civil war veterans, the railroad advance guard and those with an incurable pioneer fever, it huddled within the confines of what is now the most downtown part of Lincoln. Along O from Eighth to Fourteenth were its beginnings. The town spread slowly, like extremely cold molasses, into an indefinite shape with an undulating circumference at the present time of about 20 miles.

So, here’s O street, looking from Tenth east. Most of Lincoln’s buses head up O to Tenth, rolling around government square and then rolling back to O again. You can’t get lost in Lincoln. Just keep one foot, or at least an eye, on O and say your alphabet north and south. Or on Thirteenth and say your numbers east and west. And then there are a few streets on the edges with fancier names, just to make it a little harder.

This city is one of 25 cities or towns in the United States sharing the name of Lincoln. Sixteen of these 25 were named for Abraham Lincoln. It is perhaps not unduly vain to say that Lincoln, Neb., is most noted of these Lincolns. To begin with, it is the capital of a state, and that state is the geographical center of the North American continent.

Among other things which have drawn attention to this city of 81,000 are its illustrious one-time citizens. From the home base of Lincoln William Jennings Bryan spattered the country with silver words about the silver standard. General Pershing was one of the Atlases on whose shoulders the weight of the first World war rested. Charles G. Dawes, a dynamic young lawyer of Lincoln in the 80’s, eventually became a vice president. Willa Cather, precocious university student in the 90’s, at the height of her writing career was conceded to be this country’s most gifted woman writer. Charles Lindbergh is claimed by Lincoln after a fashion and with some degree of justification. It was here that he learned the art of flying, after trundling into town unobtrusively on a day in April—April Fool’s day in fact—1922. And there are many other notables whose names are in some way linked with the city.

The famous sculptor, Daniel Chester French, left behind him several famous statues of Abraham Lincoln. One of these has stood on the capitol grounds since its dedication, Sept. 2, 1912. As the new, and fifth, Nebraska capitol burgeoned slowly it elbowed off the grounds every vestige of the outgrown capitol with one exception—the Lincoln statue. It is something difficult to outgrow.

Lincoln was chosen as the capital of Nebraska in the summer of 1867 by three young men, David Butler, John Gillespie and Thomas Kennard, who had been named as a commission to do this task. They have become almost legendary figures in the minds of Nebraskans—three men in tall silk hats silhouetted against the prairie sky as they pounded their ponies over the countryside in search of a capital site.

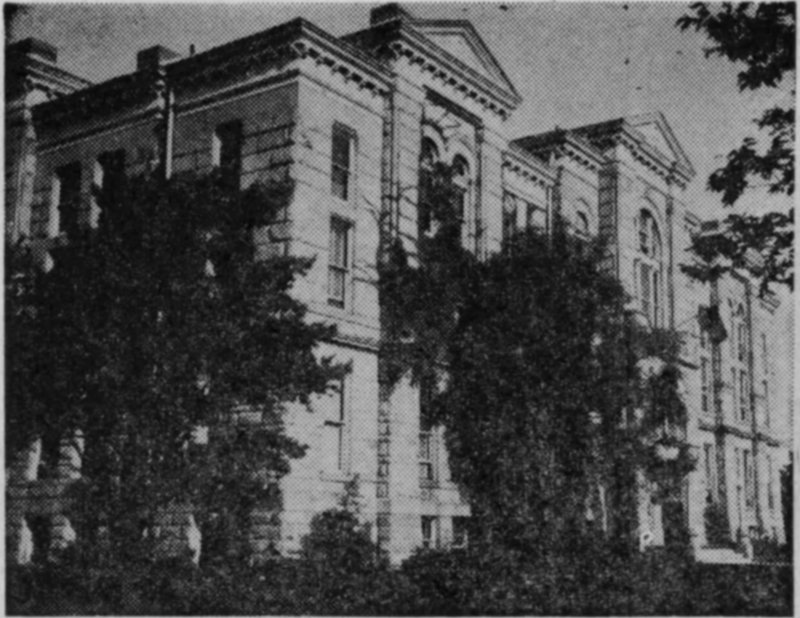

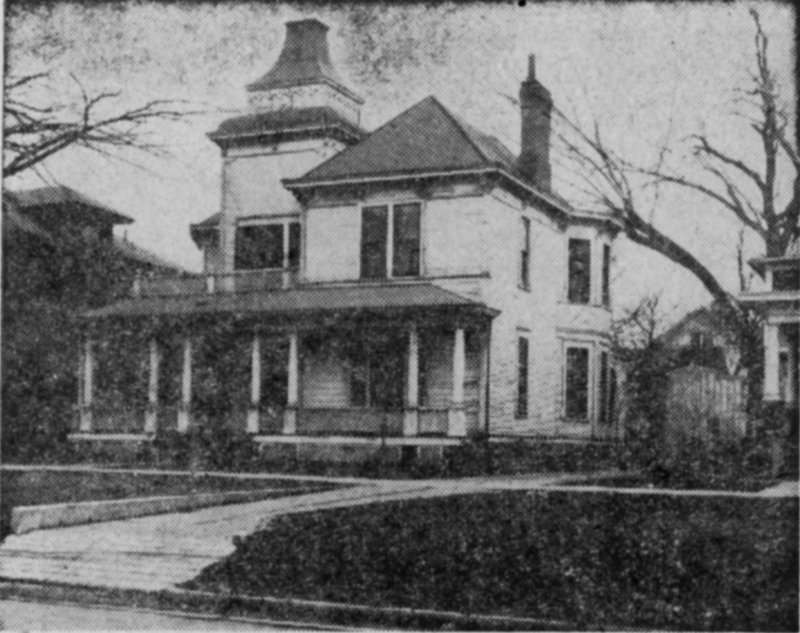

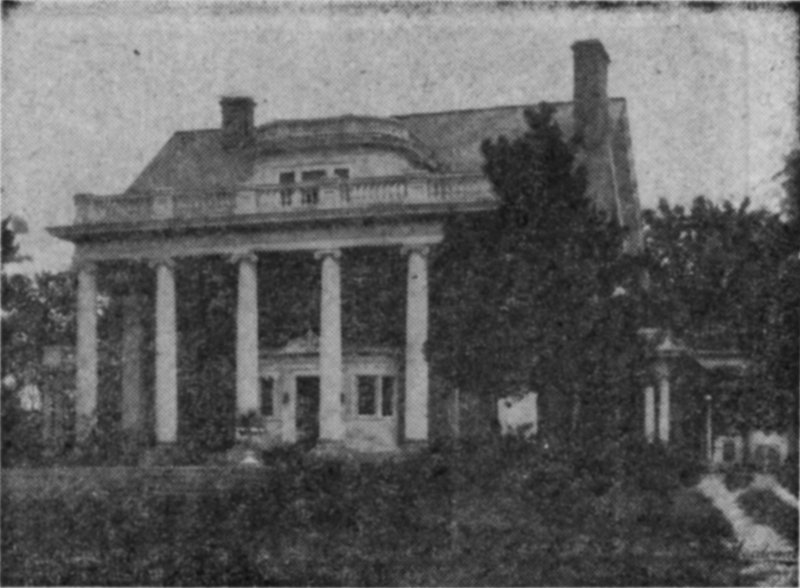

They were very actual people, however; Butler was the state of Nebraska’s first governor; Thomas Kennard, first secretary of state and Gillespie first state auditor. Interestingly, the homes built by these three men still stand, perhaps the three oldest houses in Lincoln. Herewith is shown the one-time mansion of Governor Butler, which has stood at Seventh and Washington for almost 75 years. At that time of course there were no such streets. The mansion was a country home, from which the governor drove to the capitol and back in state.

The original house was square and high. Built of blocks of brown stone with a cupola and a front stoop instead of a porch it was considered very imposing. Here Governor Butler lived from about 1867 until his impeachment in 1871. The impeachment by the legislature came about because of Butler’s borrowing $17,000 from the school fund. Land which he had deeded to the state was said to have more than paid in value the amount borrowed, and great bitterness resulted from the legislature’s action.

“Lord” Jones, a rich Englishman, purchased the building in the early 70’s. Thirty years later the Lincoln Country club took it over and added wings. The mansion has been used variously since as the home of the ku klux klan, a radio broadcasting studio and a dance house. Now, hands patiently folded, it awaits the auctioneer’s hammer.

Like the Butler mansion, the Kennard house at 1627 H was built in the late 60’s. Exteriorly it has been little changed and indicates fairly well the style of the more pretentious houses of that period.

Thomas Kennard was a colorful figure of the times. On the streets of the raw prairie city he sported a frock coat, black velvet vest and a silk hat, which was perhaps legitimate dress for a man of his importance. He had helped select Lincoln as the capital of Nebraska. Later he was railroad attorney, state senator and an appraiser of Indian lands for the federal government. In 1890 he organized the Western Glass & Paint company, still in existence. In 1898 he was appointed by President McKinley receiver of public moneys at the U. S. land office in Lincoln.

Choosing a site for the capitol was not as simple as it sounds 75 years later. Omaha clung to the honor with grim fingers. Ashland was bitter at not being chosen. The $50,000 bonds of the commissioners had been filed with the chief justice, but not with the state treasurer, as the law specified. Disgruntled Omaha people said the commissioners therefore had no legal standing and they planned to prevent the removal of the state papers, and in fact the capital, to Lincoln by having an injunction issued. Gov. Butler and Mr. Kennard formulated a plan. On Sunday morning Mr. Kennard drove to Omaha, entered the state house, took the seal of state, wrapped it up carefully and put it under the seat of his buggy. He arrived in Lincoln next morning after stopping in Ashland overnight. The governor’s proclamation, ready and waiting, that morning announced that the capital was now removed.

Mr. Kennard lived to celebrate his 90th birthday. He was by that time a gentle old man in quiet dress, yet about him still hovered, one felt, the aura of the empire builder.

The official milestone of Lincoln, standing in front of the city hall at 10th and P, has caused considerable comment, mostly favorable, since it was placed there in 1926. The suitability of the covered wagon idea and the manner of execution are not questioned. This very portion of Lincoln was alive with prairie schooners, not always drawn by oxen however, in the first 30 years of the city’s existence—tied to the hitching posts, relaxing in government square for the night. The editor of The Journal often put his head out the window and counted the wagons on the square. Then he drew it back and sat down—not to his typewriter, in those days—and told his readers how many new settlers were coming into the state. Sometimes they needed encouragement, when grasshoppers were thick or dry dust piled high.

The only critical note indicated in comment is the fact that the prairie schooner is headed east instead of west. That seems to indicate the back-home defeatist attitude rather than the on-to-victory pioneer spirit.

The city hall itself was built early in the city’s history ... 1874. For 50 years it grew dingier and dingier. Then a sandman polished it off and it showed up as an attractive edifice made of limestone—quarried near the Platte river. The texture of its surface contrasts pleasingly with the smoother face of the postoffice building.

The city hall was first Lincoln’s postoffice. Not until 1906 was the first section of the present postoffice built. Until then the city edifice was on the present site of the municipal building on Q street.

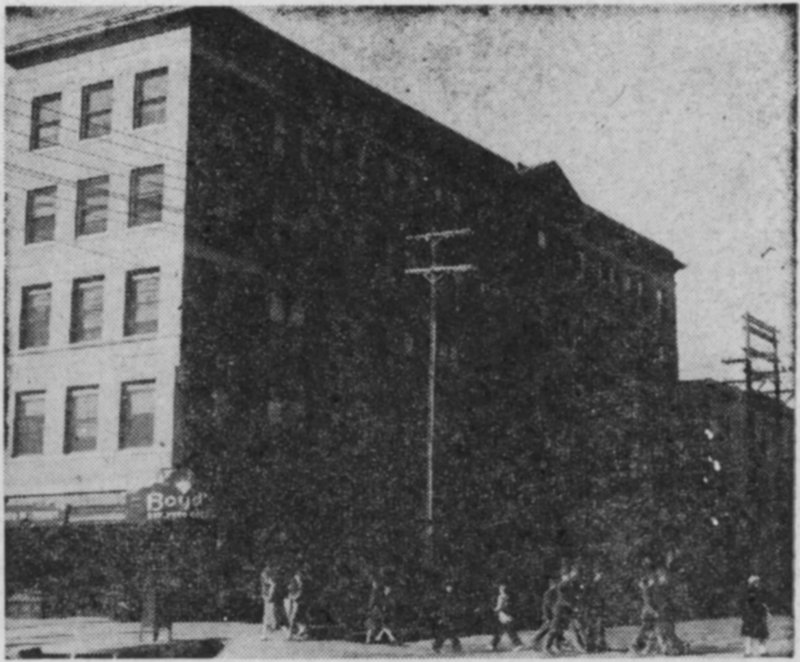

Today The Journal stars itself in this column. Justifiably, we believe. For it was 75 years ago—Sept. 7, 1867—that the first issue of the paper was brought forth, at Nebraska City, five weeks after the capital of the state of Nebraska was declared to be in existence. The next and all subsequent issues came out in Lincoln.

The present Journal building, at Ninth and P, has stood here almost 60 years. The life story of this world has pulsed thru it ceaselessly. Daily, feet have stormed up and down its steps, bearing humdrum news or perhaps a local bombshell of information. Loftily above, news from the outside has poured in over singing wires, every day occurrences of the world or sometimes catastrophic tidings.

On these steps stood Willa Cather, journalist of the nineties, a dauntless young female who nevertheless gazed about her fearfully after nightfall. For Ninth street in the nineties, and after dark, was a dubious spot. Up these steps to write his daily column reeled Walt Mason, for he had not yet reached Kansas and fame, and reform at the hands of William Allen White.

Noted people of the day sometimes came and went—sometimes a person with a grievance and a club. For newspapers of earlier days were amazingly flatfooted in their remarks. But come threat, come flood, come wars or disasters, the presses turned on, into the new century and now almost half a century past the turn.

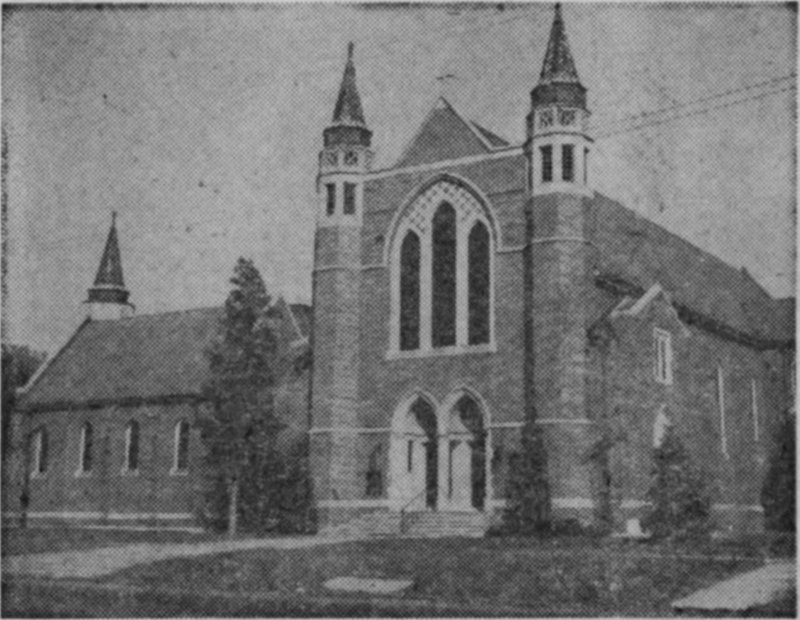

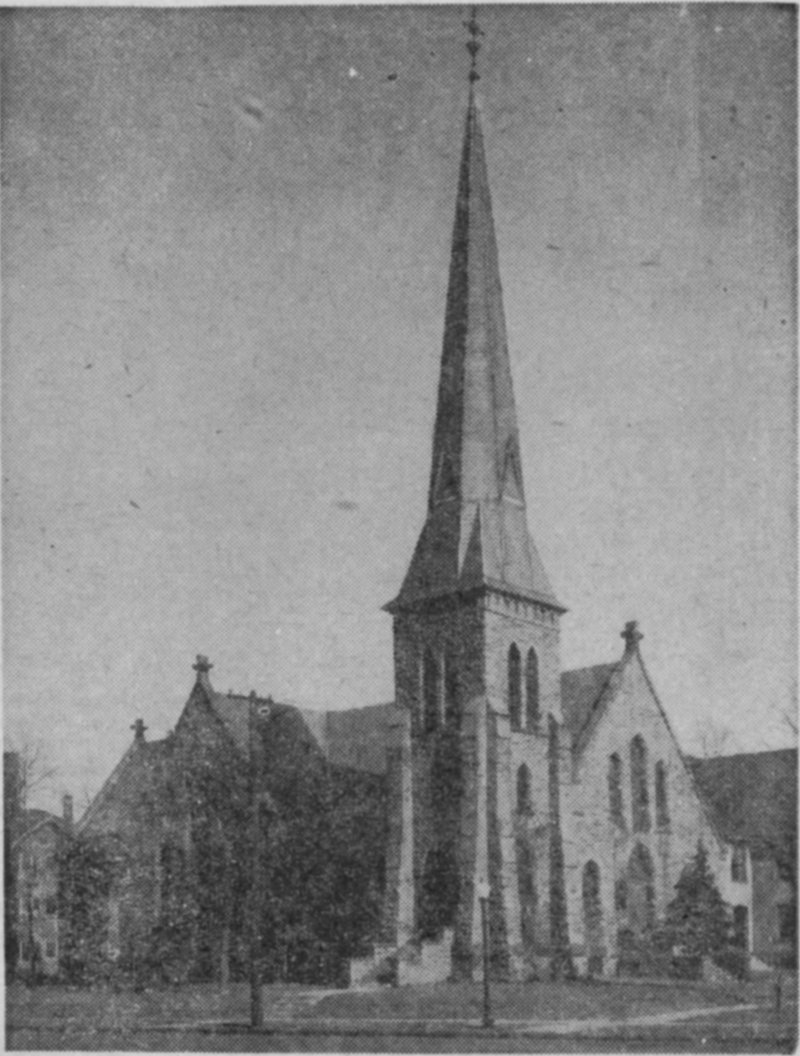

Of Lincoln’s downtown churches, St. Paul Methodist is most completely downtown. At 12th and M, the tides of business and everyday life flow all about it. It has weathered into its place, a hospitable building where passersby are welcome. St. Paul has been a boon to Lincoln during a good many years, at periods when the city was short of meeting places—and these periods have been frequent. St. Paul’s is big, it is very conveniently located. At the price of a crushed rib (and admission) one has been able to hear many stirring performances—Paderewski and other famous musicians, addresses of the great.

The crushed rib should not, however, be charged against the Methodists. Their serious purpose in 1867 was to organize a church in the new city. They expected to fling their doors open principally for church comers, and, sadly, huge entrances are not necessary to take care of the average church congregation.

The first church was put up in 1868—the First Methodist Episcopal church of Lincoln. In 1883 a new structure was erected and the name changed to St. Paul Methodist. In 1899 this building burned and two years later the present structure was completed. Among attractive features of the church are its two great windows on the east and south.

Dr. Walter Aitken, who resigned in 1942, had been pastor of St. Paul church 22 years.

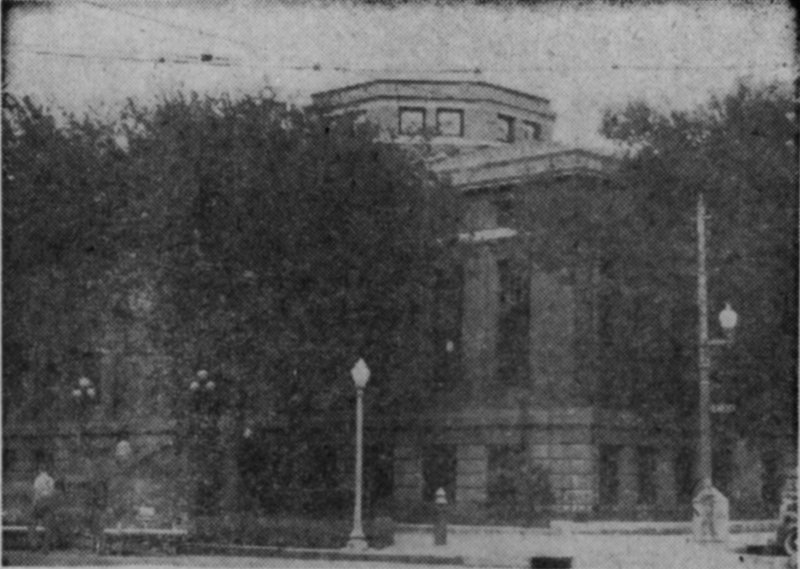

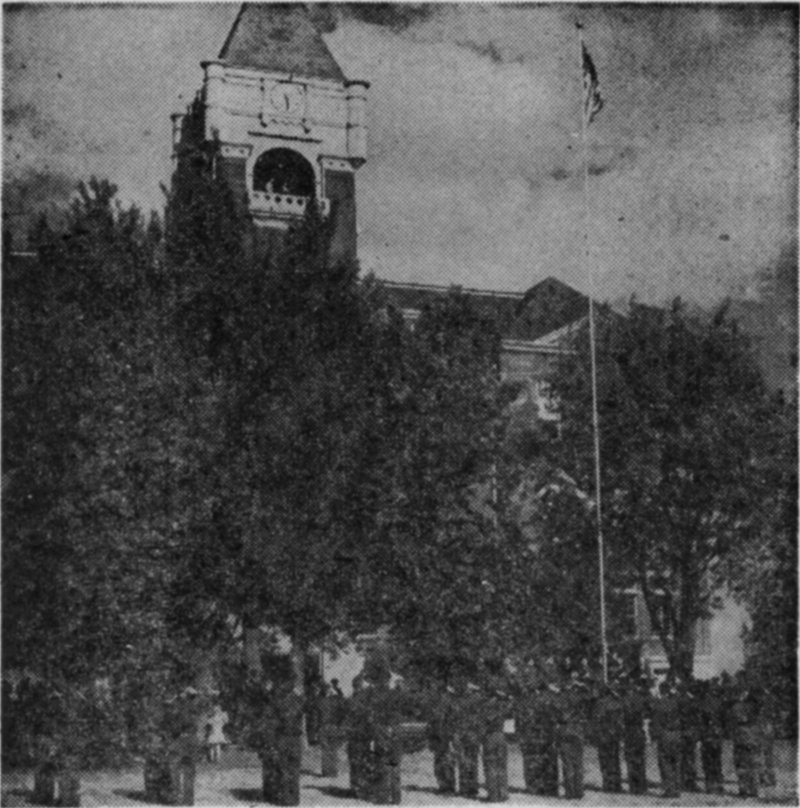

The photographer surprised us with this attractive picture of the Lancaster county courthouse, a testimonial to his art or to our lack of perception. Our initial impression of the courthouse was gained from the third story of The Journal building in the days when it still wore a conventional round dome, on top of which was perched a sad castiron statue of Abraham Lincoln. Once a painter clambered up and gave the statue a coat of bright red paint. Protests poured in. It developed that the red was only preliminary to a more suitable bronze. But eventually dome and statue disappeared, with pleasing results.

In its 55 years the courthouse has seen drama. The most sensational trials held within its walls were during the tumultuous 90’s—the John Sheedy, Irvine-Montgomery, George Washington Davis and Lillie cases. Sheedy was Lincoln’s kingpin gambler of the 90’s, a large handsome person who was found at his office with skull crushed. His beautiful young wife and a Negro, Monday MacFarland, were tried and acquitted. W. H. Irvine was tried for the fatal shooting of C. E. Montgomery, a Lincoln banker, and exonerated. Mrs. Lillie, found guilty of killing her husband at David City and later pardoned by Governor Mickey, here forced the Woodman company to pay her insurance for the death of the husband whom a jury had convicted her of killing.

George Washington Davis, a Negro, loosened part of the Rock Island track southeast of the penitentiary with the idea of notifying the company and securing a job as a reward. He notified them too late. There was a train wreck and 12 were killed. Davis was convicted.

A later incident was the trial of iron-faced Frank Sharp, found guilty of the brutal hammer murder of his wife.

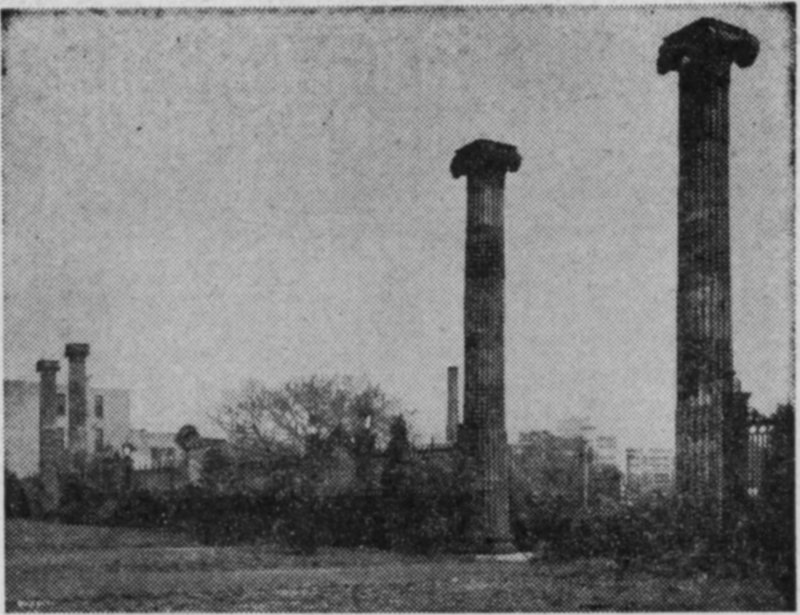

Hats off! The flag...! Shade your eyes down this vista and summon your imagination. Do you see, falling across these columns, the shadow of a great president and hear out of the past the distant marching of feet and the sound of muted fife and drum?

These columns at the O street entrance of Antelope park, between 23rd and 24th, were once a part of the old federal building in Washington. Standing between them Abraham Lincoln once reviewed the Civil war troops. Easterners, who live in an atmosphere crowded with reminders of the historic great, would smile at such a thin fancy—at attempting somehow to draw Abraham Lincoln across the Missouri river. So far as history shows, the east bank of the Missouri is as far west as Lincoln ever traveled. In the early years of the 60’s he was the guest of General Dodge in Council Bluffs, invited there to help decide where the eastern terminal of the Union Pacific should be. As we recall an early account, Lincoln stood on the bank of the Missouri and gazed westward, but even “on a clear day” such as we like to boast of from the Missouri on west, he could hardly have seen the little village which later would bear his name.

When the treasury building was remodeled in 1907 these sandstone columns were bought by Cotter T. Bride of Washington, a personal friend of William Jennings Bryan. He presented them to the city of Lincoln in 1916.

Halfway between the columns is a bronze tablet relating the origin of the pillars. The tablet, weighing 450 pounds and made from material saved from the battleship Maine, was presented to the city by the U. S. W. V.

Of the 2,811 libraries which Andrew Carnegie magnanimously scattered over this globe before his death in 1919, five stand in Lincoln—a generous proportion, surely. Perhaps we would not have shared his bounty so fully had it not been that libraries in University Place, College View and Havelock were secured when these sections of Lincoln were still towns in their own right.

Before Mrs. W. J. Bryan interceded to secure a Carnegie building for Lincoln proper the library was as wandering as a poor sharecropper, and burned out about as often. It ceased its nomadic life in 1900, beginning in that year a dignified and permanent existence at Fourteenth and N.

We have it from the librarian, Magnus Kristoffersen, that as many as 2,000 people have been known to walk up the library steps in one day—to take out books or to linger and read. That sounds like a great many people and it probably doesn’t happen often. Even so, the library is doubtless one of the city’s valuable assets. The building is richly lined with 160,000 volumes, written by the great, the near great or the fleetingly great authors of all time. No wonder readers come often to draw mental and spiritual sustenance therefrom.

An attentive staff and a carefully worked system make access to books easy at any of the library buildings. Two branches not mentioned above are Northeast at 27th and Orchard and Bethany at 1551 No. Cotner.

Any Lincoln resident, any child attending Lincoln schools, anyone attending college here or anyone owning property and paying taxes to the city will be issued a borrower’s card, good at any of the city’s libraries. In addition to regular activities, service is given the three principal Lincoln hospitals. A still newer feature is the bookmobile, which makes five stops in the city.

William Jennings Bryan, who spotlighted Lincoln from the nineties on, died in 1925, shortly after the famous Scopes trial in Tennessee. He had gone to that state to thunder disapproval of John T. Scopes, who was being tried for teaching evolution, contrary to Tennessee law. It is believed that Bryan’s death was hastened by his vigorous efforts in behalf of fundamentalism.

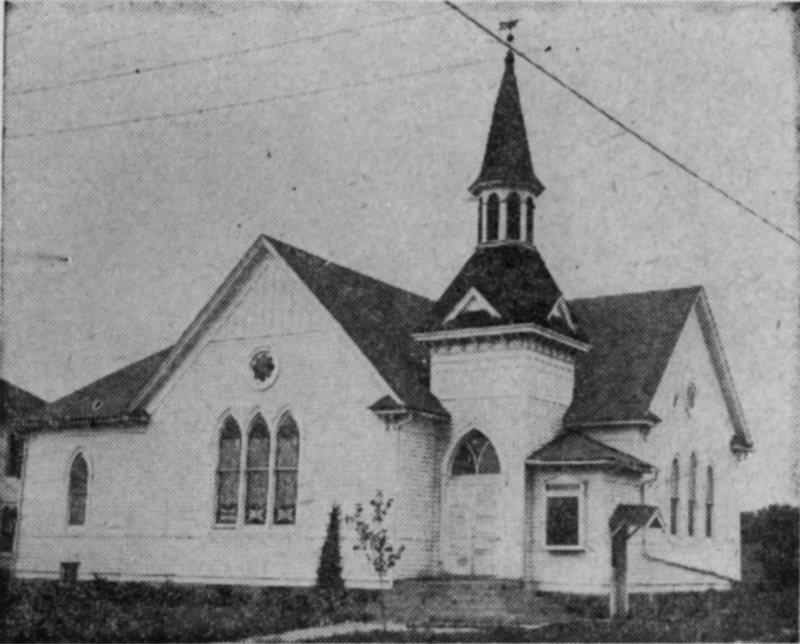

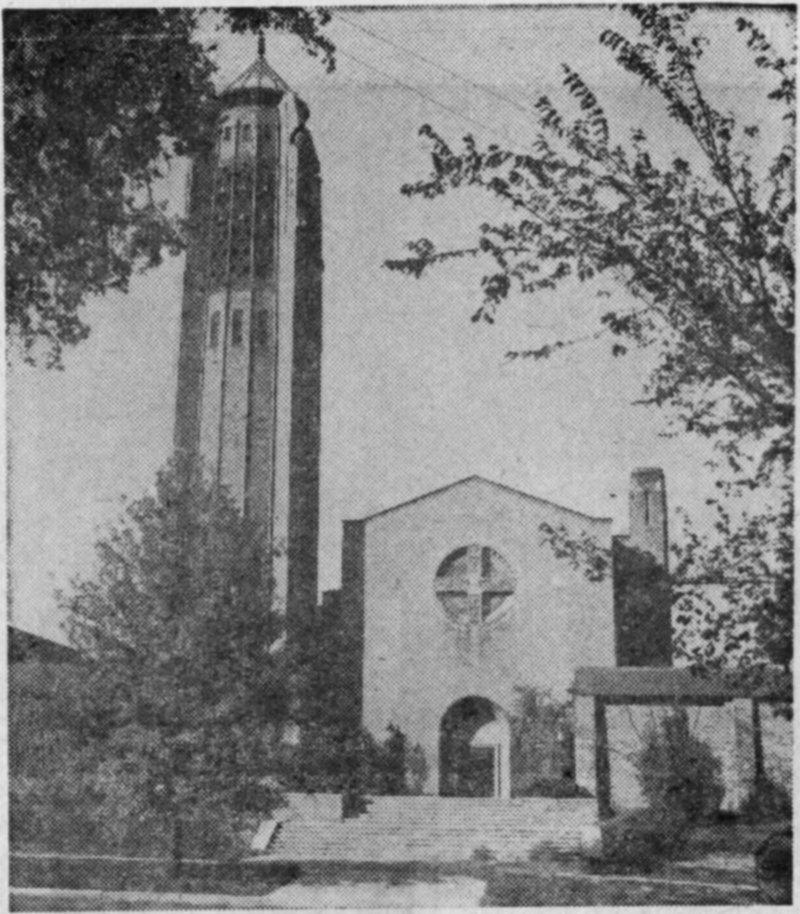

It is interesting to gaze upon this modest church—Normal Methodist, 55th and South—which Bryan attended after his removal to Fairview, and reflect that here, doubtless, were built up the religious convictions which accompanied him—perhaps hastened him—to his grave. Not always did he occupy one of the old fashioned stained oak benches. Often he spoke from the carved pulpit, his hand upon the old metal-clasped Bible, his pontifical and mellow voice filling the little church.

What W. J. Bryan believed he believed with great sincerity and articulateness. First intimations of his gifts as an orator came with the impassioned silver speech in 1896 in which he declared: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” His contemporaries did not always agree with the Great Commoner, but they could not do otherwise than respect his sincerity. He fought for the silver standard, for peace, for prohibition, for fundamentalism, often losing but never giving up the fight.

His lion’s face and mane, his broad hat, his golden voice, are gone, but gashes of his reform ax may still be seen on the surface of the commonwealth.

For years preceding and following the turn of the century 9th street was definitely a street of wickedness. In fact it was dedicated to the ways of wickedness—it and the shadowy region west, extending down to about K street. There was a law on the books against the sort of houses that filled the redlight district, but instead of enforcing it the police exacted tribute. Every first Monday of the month proprietresses in silks and plumes rustled into the city hall and majestically laid down their gold. As the rate was, we are told, about $15 for inmates and $25 for managers per month, they left a considerable stack on the municipal desk. Most of it went into the public school coffers.

This noisome neighborhood kept police busy. No mere saunter up to the station for a list of parking offenders was the police run in those hectic days. Often a brief telephone call—murder or/and suicide at Rose’s or Rae’s or Kitty’s, took police and reporters hopping. The district was finally closed by the expedient of enforcing the law. The man undertaking this revolutionary method of procedure was Co. Atty. Frank Tyrrell.

One of the well known notorious houses, known as Lydia’s place, stood at 124 So. 9th st. This same building, cleansed in purpose and aspect, was a number of years ago turned into the City Mission by interested Lincoln churches. At the top of the house a lighted star now beckons shabby wayfarers to a free meal and night’s lodging. Looking in at the mission any evening one may see, not parading painted women in short skirts, smoking cigarets—unmistakable marks of sin in the 80’s and 90’s—but seated derelicts lending their cauliflower ears to the nightly religious service.

When a blond young man, silent and tall, brought his smoking motorcycle to rest in front of E. J. Sias’s airplane and flying school at 2415 O, on April fool’s day, 1922, he probably had no idea, and certainly Lincoln had no idea, that what he learned at the flying school would one day catapult him into fame. Unnoticed Charles Lindbergh traversed the streets of Lincoln, quiet and untalkative.

After his spectacular air voyage of May 20-21, 1927—spectacular and yet on his part made as quietly as his entrance into Lincoln five years before, the flying school suddenly became a mecca. Young men were siphoned out of Australia, Scotland, China, New Guinea and dumped at the door of the school—young men talking in divers tongues but speaking the same language aeronautically. Since the war started men in uniform have almost cracked the walls of the aeronautical institute.

The name of E. J. Sias is synonymous now with the words flying school. But 30 years ago he was the energetic young minister who plucked Tabernacle Christian church out of a cocked hat before the startled eyes of south Lincoln. One day, June 21, 1912, he and a group in his home thought up a Christian church in that part of the city. Two days later they met and planned a building and 60 men volunteered to put up a structure between morning light and evening dark. The heat of late June prevented quite this much of a miracle, but anyway, on June 30, nine days after the initial meeting, the tabernacle was ready for occupancy. Rather, it was occupied—by 800 people listening to the dedicatory sermon. This building sufficed its congregation ten years. By that time Mr. Sias was deep in something else—flying.

The postoffice is a noble building, filling half a block on P street between Ninth and Tenth. But, mysteriously, filtered thru a picture-taker’s lens it takes on the appearance of a toy model still sitting on the architect’s desk. This is most deceiving. It is really a handsome and majestic building, of Bedford stone, standing very massively on its green lawn.

It isn’t just a postoffice, as you learned when you were initiated into the Income Taxpayers lodge. Also, if you want to ask how about that money you’re going to get from Uncle Sam when 65, how about a loan for putting up a hog house, how about keeping the black dirt on your farm from drifting into the Missouri, how about enlisting in the army or navy, you go to the postoffice—and also the FBI will reach out from the postoffice and get you if you don’t watch out. If the United States wants to try you for some federal offense, that’s where the trial will be. Having steered clear of this court, the only case we recall offhand is the Nye committee hearing in the Grocer Norris senatorial case.

The first federal court was held in November 1864, in a log building on the south side of O between Seventh and Eighth. Elmer S. Dundy was the judge. The postoffice was run by Jacob Dawson in conjunction with a grocery in the front end, so that office and courtroom were enlivened with the smell of codfish, coffee and tobacco. Somewhere within the log cabin and between the codfish and the cases at bar Mr. Dawson kept house—it may be with the help of a Mrs. Dawson, but one can read early histories of Lincoln from preface to index without finding mention of a woman, so thoroly was the sex still in subjugation.

The postoffice began taking on dignity in 1879 when it moved into its new building on government square, now the city hall. The first section of the present building was put up in 1906; the last, which made it the impressive edifice it is today, only a year or two ago.

Some day when you emerge from the Varsity, 13th and P, and look up at the weather your eyes may come to rest on “The Oliver” in old fashioned lettering on the battlements of the ancient building, and for a moment you may idly wonder about the playhouse’s past. It does in truth have considerable past, reckoned in terms of famous actors who trod its boards, of orators who thundered in debate over silver and gold standards, suffrage for women and other problems of the past.

The theater, first known as The Lansing, opened in 1891 with Ed Church in charge, and with Lillian Lewis and her company gracing the stage in “L’Article 47” with the sinister subhead “The trail of the serpent is overall.” Yet Gen. Victor Vifquain, rhapsodizing in the opening night souvenir booklet, said: “The Lansing will become an athaeneum where a husband can take his wife and daughter, the brother and sister without fear of bringing a blush upon the cheeks of those whose modesty is of priceless value to them and to the community of which they are the ornaments and the pride.” Anyway, it was a good old chest-expanding sentence.

A Journal man who has attended shows at this theater off and on for 50 years gives us the following list of famous players he recalls having seen at the Lansing (later Oliver): John Drew, Ethel Barrymore, Edwin Booth, Laurence Barrett, Joe Jefferson, Emma Eames, Sol Smith Russell, Blanche Bates, Billie Burke, George M. Cohan, Weber & Fields, Willie Collier, Otis Skinner, Maxine Elliott, Robert Mantell, Elsie DeWolfe, Nat Goodwin, Dustin Farnam, Minnie Maddern Fiske, Trixie Fraganza, DeWolfe Hopper, Virginia Harned, Elsie Janis, Margaret Illington, Mary Mannering, Julia Marlowe, E. H. Sothern, Lillian Nordica, Alice Nielsen, Chauncey Olcott, May Robson, Eleanor Robson, Stuart Robson, Madame Modjeska.

Vividly connected with the history of the theater, as it is with Lincoln itself, is the name of Frank C. Zehrung, to whom death came recently. For almost 70 years a citizen of Lincoln, he was for perhaps half that time manager of the Oliver.

Before winter puts out a white hand to stay us (which we trust won’t be soon, altho there are hints of early frost), it would be pleasant to make a tour of Lincoln gardens. However, we wouldn’t want to flatten our sight-seeing noses against front windows, and the gardens which can be seen entire from the street are few. In a simpler day, we Americans put our iron deer and dogs, petunias and hollyhocks in a big front yard and then naively sat on our big front porches to see passersby and have passersby see our elegant homes and lawns. Now that we have grown more subtle and English and hide gardens in the back and put inscrutable faces on our houses, seeing gardens on a tour isn’t so easy. But the gardens are there and one can get pleasing glimpses.

Imagine a Lincoln in which all the houses perched desolately on barren lots. Not a tree, not a curving path, not a flower. Then you will indeed appreciate those patient and imaginative garden lovers who with a few rocks, seeds, hoes and hoses turn desert lots into oases. There are pretty little gardens around modest houses, large beautiful gardens around mansions, altogether making Lincoln a charming lady of gardens.

Peer with us thru Dr. Harry Everett’s gates at 2433 Woodscrest for a glimpse of his delightful ivory complexioned house with its maroon awnings and blue windows, and his formal garden. Dr. Everett is an iris specialist and is or has been president of the national iris society.

So charming is this quiet scene, with the September sun falling in bars across the lawn, the soldierly evergreens silently on guard, that even the sudden appearance of five beautiful senoritas on the five balconies would be an intrusion not to be desired.

Doubtless you know the delightful and intimate sound of rain which only a staunch immediate attic roof keeps off your face. Walking into the Chapin home at 3805 Calvert one has a similar pleasurable sensation. It is a beautiful house, and of course actually very protective, yet one has the feeling of being near the earth—still in the garden. This possibly comes from walking into it levelly from broad low flagstones. Inside one looks out thru great wide-eyed windows so flawless that he seems not to be separated from the rock garden and its mountain stream or the green plush lawn which falls away into the wood.

We grew up near the woods, but “the wood” seems more suitable for this fairy house (glorified French peasant). And the nicest thing about these trees which circle the Chapins’ two and a half acres is that they are original ones and came along free with Nebraska. Luckily the recent dry years—do you remember them—did not affect the small forest, in which hundreds of birds sing.

Inside, as the earth slowly turns, the Chapins can watch the seasons as on a stage, or as a great framed picture turning slowly from green to russet and brown, from brown to white. On the sloping green outside a silver gazing globe pictures the lawn in miniature.

One could exclaim over many things—the garden to the north, where a thousand gladioli grow—the balcony from which one half expects a pretty peasant girl or a blessed damozel to lean.

What, in the words of the atrocious daily puzzle of that name, is wrong with this picture? Very easy indeed. No angels in flat heels and sweaters are ascending and descending the stairs. Actually, they have begun the continuous zigzag on the Student Union steps for the season. They may be going to or coming from a spot of lunch in the Corn Crib, a friendly coke, bridge or pingpong, time out on the marshmallow upholstery of the lounge, or a late afternoon hour dance.

And cease your sighs and murmurs that when you and I were young we had lessons to get and nobody put us up a Student Union building. For one thing, the tots may have mastered all lessons up to and including next Tuesday morning. For another, the building is theirs, or will be in 80,000 easy payments. At six dollars a year, 10,000 university educations laid end to end ought to about close the Student Union books.

Incidentally, it’s well worth two and a half cents a day to city campus students, especially the ones who have made no entangling alliances with fraternity or sorority, and they’re in the great majority—probably 75 percent. Here’s a place to do almost anything you can think of—or they can think of, which is more comprehensive.

In the basement are offices of student publications, Awgwan, Cornhusker and Daily Nebraskan and a ping-pong room. Office of building manager, grill room, cafeteria, lounges and book nook are on first. On second floor are offices of alumni association, university foundation and University speakers bureau, ballroom, dining rooms, game room and faculty lounge. Dining rooms and student organization rooms occupy the third floor. Mortar Board and Innocents have fourth-floor dormer rooms.

To get the desired three by four inch view of Nebraska’s stadium a photographer might walk around it seven times and his pursuit would still be in vain, for it ovals away from him endlessly. One could get a pointblank shot at it from the air, but empty seats, even people enmasse, bundled in blankets, aren’t as attractive as arched windows, which lend beauty to the mammoth structure. In the foreground of this picture is the military department’s reviewing stand, which furnished not only requisite proportions but perspective suitable to the times, war now having put college athletics in the background with no gentle hand.

The stadium, which holds 30,000 without the bleachers, is a memorial to U. of N. men who have died in the nation’s wars. The half million dollar cost was defrayed by students, faculty, alumni and friends. Many a tonsil shredding joust has taken place within the stadium’s great arms. The following from the helpful typewriter of Walter Dobbins gives details:

“The first game played on stadium sod was with the Oklahoma Sooners, Oct. 13, 1923, just a week before dedication of the bowl. With its building Nebraska became a ‘big time’ football school. Games were scheduled with top flight teams from north, south, east and west. The largest crowd ever packed into the home field witnessed Nebraska’s 7 to 0 victory over Indiana Oct. 20, 1937.

“Some of Nebraska’s gridiron triumphs have been recorded at the stadium, including the amazing 14 to 7 victory over Notre Dame’s Four Horsemen in 1923; the 17 to 0 win over Rockne’s eleven in 1924 and the last of the 11 game series with the Fighting Irish. New York U.’s national title hopes were blasted on the same field in 1926 and 1927. Greatest of all victories, however, are later ones—the 14 to 9 defeat of Minnesota in 1937 and the 6-9 win over the Gophers in 1939.”

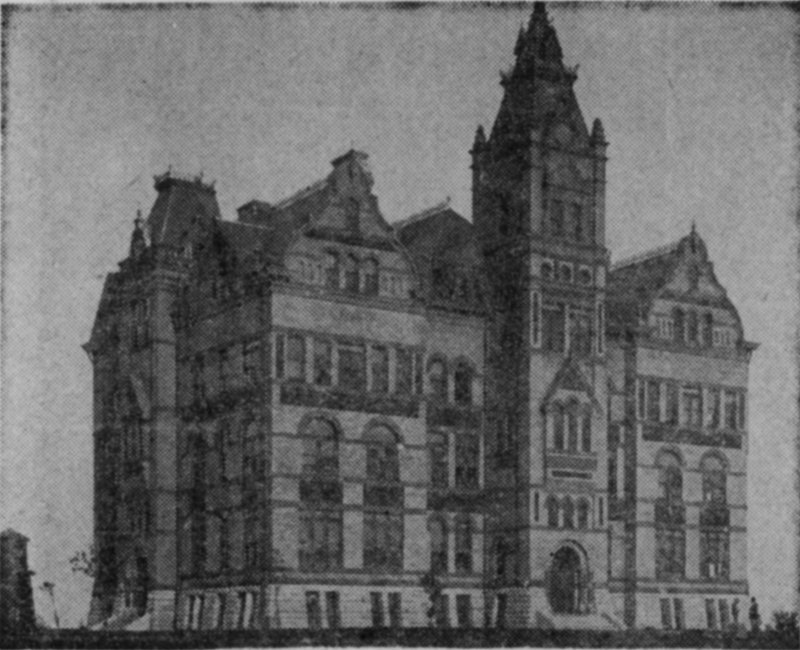

This decapitated building may look ready for the scrap heap, but sentimental Nebraskans would indignantly refuse to have it scrapped, for it is the remains of the original campus building. Once it housed the university entire, even offering sleeping room on the two upper stories for men students.

First recollection invoked is of “Miss Bishop,” Bess Streeter Aldrich’s filmed story of primitive university life, which had its premiere in Lincoln. Another is Oscar Wilde’s visit to the university in the eighties. There, garbed in his eccentric finery, he walked unhappy as a strange cat, distressed by the uncouthness of Nebraska and its university and especially by the ugly castiron stove which heated the premises. After expressing this distress, along with his regular lecture, Wilde, in knee breeches, buckled slippers and velvet coat, shuddered his way back to the Arlington hotel, 841 Q, and was soon lost to this region forever. Nobody was depressed over his disapproval and irrepressible Journal reporters put him and the castiron stove into facetious rhyme.

The cornerstone for U hall was laid Sept. 23, 1869, with ceremonies—Masonic ceremonies, in fact. An Omaha brass band led a procession and a thousand people banqueted—which must have more than depopulated residential Lincoln—then danced until 4 in the morning.

Lumber for the building was shipped from Chicago to Nebraska City and thence came slowly over the hills in wagons. Brick was burned in a kiln on Little Salt creek. On Jan. 6, 1871, the doors swung open and in walked ninety young men and women. Rumors that the building was unsafe continued off and on for fifty years. Every now and then some propping was done. Finally the two top floors and belltower were taken off, but classes are still held on the remaining first floor.

The beautiful new library, now North Thirteenth’s visual shortstop, will make 1871-1942 students brothers to the pioneer who slept, ate, cooked, played and quarreled in one room. The new edifice has a student lounge, auditorium, social studies reading room, general and humanities reading room and browsing room. Those who did their lounging, their browsing, their studying of the humanities and their date making all in one big room under an uncompromising row of green shaded lights will feel outmoded indeed.

But casting envy aside, this generous gift, one of several from the late Don Love, is a welcome addition to the campus and the city. True, it turns its back on the city as it communes perpetually with its sisters of The Quadrangle—teachers’ college, social sciences and Andrews hall—but it is a slender ribbed, sightly and aristocratic back. Earlier buildings were sardine-packed on a small campus. Later edifices, given space on the avenue, took on social graces. To the north of the quadrangle, Memorial mall forms the center of another group of aristocrats—Morrill hall, Bessey hall, Memorial stadium and the Coliseum.

The new library is not yet completed. We had wondered if, when the day of occupancy came, the former library would go the way of the old cannon which once stood guard beside it. This cannon, brought to the campus from the fortress of Havana at the end of the Spanish-American war, was dedicated with ceremony as a memorial to Nebraska students who had fought for Cuban freedom. The cannon had stood in Seville in the time of Charles III of Spain.

A few weeks ago the cannon was ignominiously trucked off for scrap, without ceremony or apology. But the library is to remain and will now house the university’s extension department.

That rugged old warrior, Grant Memorial Hall (campus, 12th and S) now resounds to commands no more stirring than a set-up singsong to which co-eds stretch muscles and limber joints in accordance with university physical education requirements. It was built, however, for sterner purposes. Once the shuffle and click of guns could be heard within its soldierly exterior as Lt. John Pershing sang out brisk orders to his cadets. The hall was erected in honor of Nebraska’s Civil war veterans in 1887, when those veterans were comparatively young men. Pershing was commandant from 1891 to 1895. The military department is now housed in Nebraska hall, a block to the north.

During the university’s middle years convocations were held in Grant Memorial. The pipe organ in the west half of the second story came from the Mississippi exposition held in Omaha in 1898. It was a gift from alumni who purchased it for $2,500. For years Carrie Belle Raymond, for whom one of the girls’ residence halls is named, played the organ for convocation. Thousands of graduates recall her always smiling face as she sat high above them, fingers hovering over the organ keys.

In Grant Memorial also are housed the U. of N. radio studio and the department of architecture.

With the exception of the school of music, which began as a private institution, The Temple, at 12th and R, is the only university building which does not stand on the campus. The reason for this seeming ostracism of the Temple—indeed, actual ostracism at the time it was built, is that it was a gift from John D. Rockefeller, jr. The time was 1906, when muckraking and Rockefeller reviling were at their height. Rockefeller had been a student at Brown university when E. Benjamin Andrews, in 1906 chancellor at Nebraska, was its president.

The name of Rockefeller and the smell of oil were offensive to those who had to do with accepting and placing buildings, but the gift was not quite to be refused. The Temple was delicately dropped outside the gates. However, the Temple has been a useful and busy edifice these 35 years, and but for reporters with fingers always crooked hungrily over typewriter keys old ghosts would not have been disturbed. The Y. M. C. A. has used the Temple for headquarters and other innocent activities have been housed therein.

Principally, however, the building is known as the theater of the University Players, Lincoln’s theatrical stock company, personnel of which consists of instructors and advanced students of dramatic art. Six plays are presented each university year. Here Fred Ballard’s “Believe Me Xantippe” had its premiere—Mr. Ballard being a university student some 35 years ago. His more recent “Ladies of the Jury” also appeared here, but not the premiere. A number of the players have become known elsewhere—Zolly Lerner, Augusta French, Jack Rank and others. The name of Miss H. Alice Howell, for years director of The Players, is inevitably connected with this organization.

Morrill hall, 14th and U, is a spot on the campus where everyone is very welcome. In most of the campus buildings, while by no means barred, one is likely to be run down by a horde of young things charging to a class. As they outstrip one on the stairs he is left acutely aware of his brittle old bones and the fact that from college days he can recall offhand only two French verbs and one theorem.

In this hall—named for Charles H. Morrill, Nebraskan who did a great deal for the university—you may saunter and look, and look and saunter. The art galleries are in the two top rooms, the museum on the two below. Dwight Kirsch of the university art department caught this particular slant of sun into the upper art gallery.

Like the native Chicagoan who never heard of Hull House, we know too little about what we have at our own doors. The Nebraska art association has built up a fine collection of paintings. Each year it holds an exhibit, and the fact that it buys one or more pictures every year brings in a collection worth inspecting. The late Mr. and Mrs. F. M. Hall of Lincoln bequeathed their collection to the university, also a fund for further purchases.

Among the valuable paintings by modern artists owned by the art association are the late Grant Wood’s “Arnold Comes of Age,” one of Thomas Hart Benton’s vigorous paintings, “Lonesome Road” and John Steuart Curry’s “Roadmender’s Camp.”

Most impressive, perhaps, of the many interesting rooms in the Morrill museum—two lower floors of Morrill hall—is Elephant hall. In this quiet room time yawns, and down her great throat one sees the endless vista of the years. Here animals of all eras, usually clad only in their bones, confront one. If you are sensitive to the ghostly whispers of the past you might well bring a companion. To span millions of years alone in an afternoon is too much; the winds between as the centuries whirl are too vigorous.

Last Saturday we gazed, alone we believed, at a beautiful pair of albino coyotes (Wheeler county, Nebraska, 1940) with touching blue eyes; at a Peruvian mummy (pre-Inca)—a baby with its little skull resting on moth eaten arms; at the skeleton of a dawn horse, no higher than your knee, dug up in Sioux county, and were kneeling intent before a reconstructed dodo when we turned suddenly and encountered the saturnine eye of the ever present guard.

Rightly, the museum takes no chances. Elephant hall contains one of the best collections of modern and fossil elephants in the world, and in addition real or reconstructed animals of many ages. Backgrounds for these reassembled bones of animals which sniffed the earth when it was new were painted in delicate tints by Elizabeth Dolan. The late Gutzon Borglum, stepping into Elephant hall in a woolly camelskin coat, stopped in his tracks among the ancient bones and murmured paradoxically and appreciatively, “A new world.”

One of the activities of the museum has been research on the antiquity of man in North America. Many discoveries have been made in Nebraska, and one of the few existing collections of Yuma-Folsom artifacts is to be found here.

The pattern has changed since grandmother attended the University of Nebraska in 1871. Today’s co-eds glide thru their four years of college with a minimum of discomfort. Grandmother undoubtedly led a more vigorous life, tho it cost her less (but again, money was money then). Lincoln’s few citizens were urged to be kind to open up their homes to farmers’ daughters bent on education. Or she could stay at “ladies hall,” which our sleuthing has led us to believe stood at 14th and U, for 50 cents a week if she toted in her own bedstead. Wherever she stayed, chances are she often had to crack ice on the water pitcher winter mornings. And crossing the pasture toward University hall in temperate seasons she ran the risk of falling over someone’s tethered-out cow.

In the evening grandmother lighted her kerosene lamp in a chilly room and sat down to her lonely studies—perhaps with her chilblained feet asoak. She was more or less isolated, as phones were still missing from the Lincoln scene. If it had been arranged in advance, she might meet other young men and women for a candy pull or sleigh ride.

Now, in Carrie Belle Raymond, Julia L. Love and Northeast halls—on No. 16th—the way of the co-ed is smooth. She may roam at large over an area predigested as to temperature, blossoming with deep chairs, radios, cardtables, piano, shampoo rooms, dancing halls and tennis courts. Fifteen sororities in the region of the campus furnish approximately the same sort of living for grandmother’s granddaughter. Others take their living places where they find them. But even at the worst those living places are much superior to what was the common lot in 1871.

To old timers, the Bryan home is not the nurses’ residence at Bryan Memorial hospital, but the house at 1625 D. It was while an occupant of this house that fame suddenly embraced William Jennings Bryan. From it he went to two national conventions, returning from each with the democratic presidential nomination. On his return he addressed his people. A sea of faces strained upward on D from 16th to 17th as the sound of his mellifluous voice flowed out from the balcony on which he was standing.

Here his two younger children were born. From it, in a one horse surrey, William Jennings Bryan, in broad black hat, with his wife and children, sallied forth each Sunday afternoon for a drive. In the backyard the children—Ruth, later U. S. congresswoman and minister to Denmark, William jr. and Grace dug an elaborate cave which was the envy, and the daytime abode, of neighbor children.

As late as 1935—when the above picture was taken, the house was much as it had been built originally. Now the square tower is gone the way of the porch and balcony. The edifice is corseted tight as an armadillo in white asbestos shale. We offer the original so that, driving past, you may attempt to trace it in the modern version. At least it is an interesting example of a 50 year old house rejuvenated.

Seven years ago the department of the interior suggested the old Bryan home as a historical American building, worthy of careful preservation. There was some talk of making a national shrine of the home in which the Great Commoner had experienced his greatest triumphs. But the movement drooped, and the old dwelling is now tamely serving as a four family apartment house.

Standing lonely on its hill this old house, doubtless one of the oldest in the region, is the only visible evidence of one of Lancaster county’s early and to be noticed citizens, John F. Cadman. As time has shorn him of earthly glory, so has it shorn the house of pretentious tower and galleries which graced it in its original elegance as manor house of Silver Lake farm. In those days it was embellished with laid-out garden and tree plots, even a fountain.

Mr. Cadman was a man of vigor and action. Coming to Lancaster in 1859, he entered a quarter section of land on Salt creek, south of Lincoln. His first move was to open a cut-off (from the Oregon Trail) from Nebraska City to Fort Kearny, which he completed in time for 1861 spring travel. This was of great benefit to farmers on the Salt and Blue. In addition to his farming operations he established a trading post at the point where the cut-off crossed Salt creek. The post was also a station for the Lusbaugh line of stages between Nebraska City and Fort Kearny, where they connected with overland stages to California. He served in the territorial legislature, also the state legislature, first term. In 1867 he was a leading advocate for removal of the capital to Lancaster county—only he wanted it at Yankee Hill, south of Lincoln.

An old biography of Mr. Cadman says proudly that he never drank a glass of liquor in his life, not indicating, we hope, that he was a rare exception to a general rule. All in all he was a hardy and to-be-relied-on citizen, a worthy rival of salty old Elder Young, who founded the town of Lancaster and used his influence to get the capitol into Lancaster’s successor, Lincoln, instead of at Yankee Hill, where John Cadman wanted it.

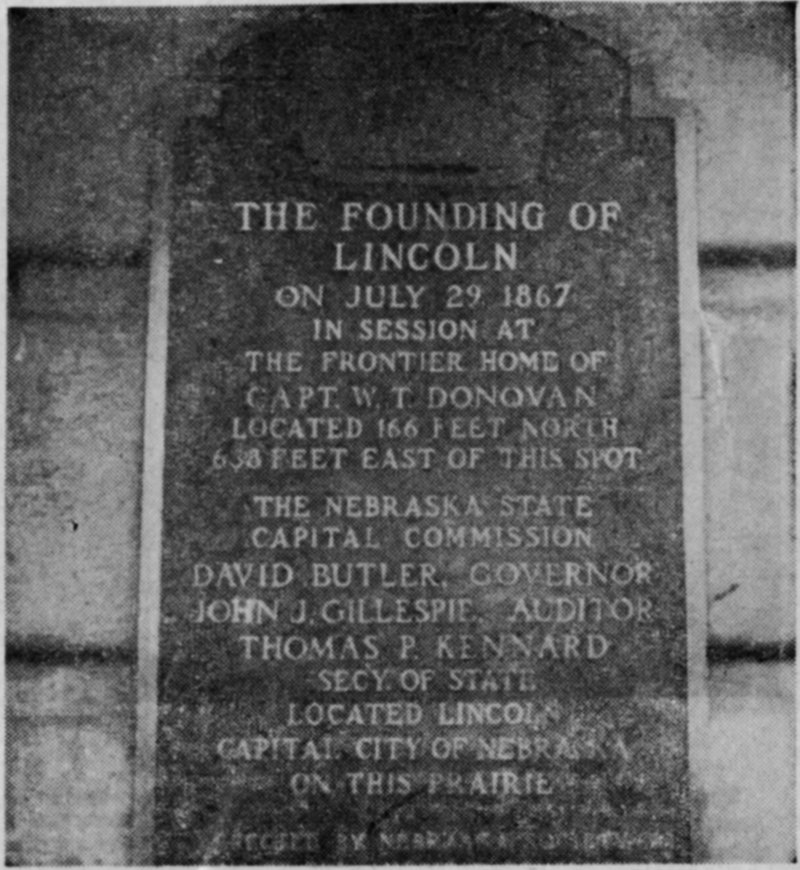

THE FOUNDING OF

LINCOLN

ON JULY 29 1867

IN SESSION AT

THE FRONTIER HOME OF

CAPT. W. T. DONOVAN

LOCATED 166 FEET NORTH

638 FEET EAST OF THIS SPOT

THE NEBRASKA STATE

CAPITAL COMMISSION

DAVID BUTLER, GOVERNOR

JOHN J. GILLESPIE, AUDITOR

THOMAS P. KENNARD

SEC’Y. OF STATE

LOCATED LINCOLN

CAPITAL CITY OF NEBRASKA

ON THIS PRAIRIE

ERECTED BY NEBRASKA SOCIETY

SONS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

JULY 29 1927

On a hot afternoon in July, 1867—the 29th—Commissioners Butler, Kennard and Gillespie emerged dripping from the attic of Captain W. T. Donovan’s house. Standing on its east side to avoid the blazing sun Butler announced that henceforth Lincoln would be the capital of Nebraska. The severely fashioned Donovan house stood at the northern point of a triangle which would have included the Journal building and the Burlington station had they been built at that time. Why the commissioners took to the attic to vote on the site is not certain, but possibly they did not want to be rudely interrupted by those who had been insisting that it be located at Ashland, Seward or Yankee Hill, or be left in Omaha.

Captain Donovan came to Lancaster county in the mid-fifties. Captain of the steamboat Emma, one of the boats which plied up the Missouri as far as Plattsmouth, he was drawn to this region by the possibilities of salt in the Salt creek valley. His son was the first white child born in the county, his daughter the first Lincoln bride. He took the first homestead in the county under the 1862 homestead law. He stuck to his claim during the Indian scare of 1864 and helped protect settlers who had the courage to remain. The tablet was erected by the Nebraska Society of the Sons of the American Revolution.

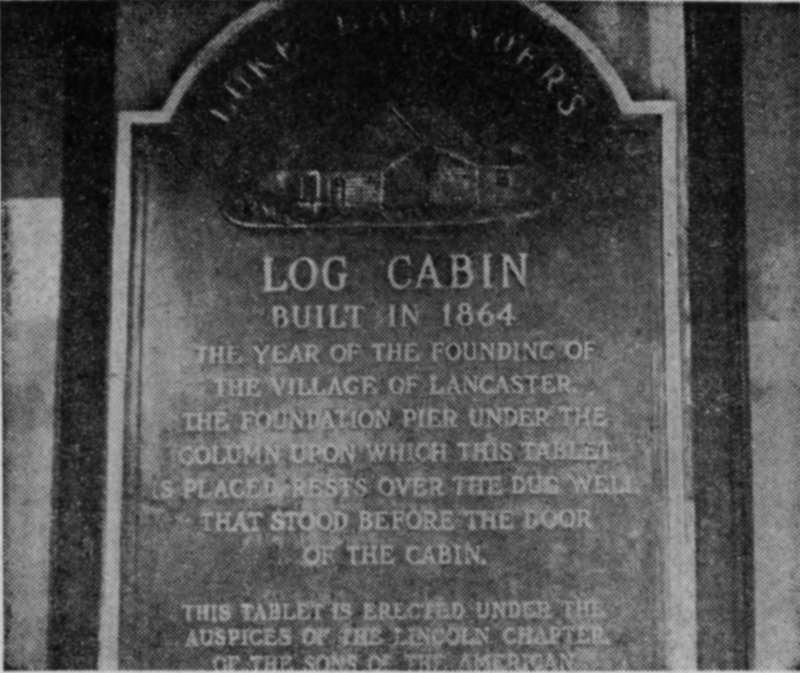

LOG CABIN

BUILT IN 1864

THE YEAR OF THE FOUNDING OF

THE VILLAGE OF LANCASTER.

THE FOUNDATION PIER UNDER THE

COLUMN UPON WHICH THIS TABLET

IS PLACED RESTS OVER THE DUG WELL

THAT STOOD BEFORE THE DOOR OF THE CABIN.

THIS TABLET IS ERECTED UNDER THE

AUSPICES OF THE LINCOLN CHAPTER

OF THE SONS OF THE AMERICAN

REVOLUTION.

The name Luke Lavender seems inevitably to have been coined by some feet-on-the-desk writer of westerns, perhaps as a brother in literature to the outlaw Violet in MacKinley Kantor’s “Gentle Annie.” But Luke Lavender was not invented. He was a rather important citizen of Lancaster and Lincoln, often referred to as “Judge” and apparently also a builder of carriages. He put up the first house in Lincoln, at what is now the southeast corner of 14th and O—in 1864. It was a neat log cabin with two leantos, and to the south and east stretched Mr. Lavender’s farm.

Try, for a moment, to erase with one giant gesture all that now means Lincoln. Visualize a bit of lonely prairie, hummocky and irregular. A creek ran along the M and L street region. A hill of considerable height rose where the postoffice now stands. The silence was rarely broken. Light-footed antelope made no sound as their feet lightly trod the grasses and their delicate ears pricked at the sound of an occasional interloper. The night, however, was sharply punctured at intervals by howls of wolves and coyotes. To the west was the illusion of perpetual snows, for Salt basin was covered with an incrustation of salt about a quarter of an inch deep.

Mr. Lavender was an Englishman who came here with Elder J. M. Young in 1863. Among the party were Jacob Dawson, who a little later built half a mile to the west of Lavender, Dr. McKesson, Edwin Warnes, Thomas Hudson, John Giles, Uncle Jonathan Ball and others. These settled elsewhere in Lancaster county. It was Elder Young, leader of the colony, who laid out the town of Lancaster and a little later started a female seminary at 9th and P.

This is Oak lake, in Lincoln’s newest park—1st to 14th, Y to Oak, 279 acres. If you are unimpressed, please remember two things: First, a nice expanse of blue water is never to be looked down the nose at, especially in a prairie city. Second, it is a wonderful improvement on the magnificently proportioned dumping ground which used to occupy the same quarters, and over which roamed unfortunates peering and picking at bits of refuse. Things have been done to Oak creek, so that its main channel now runs thru the center of the park. Between it and Salt creek lies the lake, which members of the Lincoln boat club rejoice in as a place to hold races.

The park site was once a part of the great salt flats whose glistening white blanket drew early settlers to Lincoln. In fact, these saline lands took a prominent part in the early history of Lancaster county—in the courts, in politics, and elsewhere. Both Governor Butler and J. Sterling Morton were involved. Morton had put up a log cabin on the flats and pre-empted the basin in 1861. In 1870 Butler leased the flats. Endless complications and lawsuits resulted. In the end Butler was forced to pay thousands of dollars to the state.

The salt industry, from which so much had been hoped, failed for several reasons—importation of cheaper salt from Utah, the difficulty of forming large areas into drying pans, and the destructive rains and overflows which for 80 years have bedeviled the Salt creek bottoms. The last named situation the sanitary board has been battling with renewed vigor since the disastrous flood of May, 1942, with considerable promise of success.

Returning to the subject of parks, Lincoln is liberally sprinkled with them. We have 22, in assorted sizes.

One day in 1928 John F. Harris, a New York financier who had grown up in Lincoln in the seventies and eighties, met a boyhood friend who still lived here. The rusty gate of memory swung back—it had been 40 years since Harris left Lincoln—and sharply accentuated before him stood the past. In a rush of deep affection for all that had gone into his boyhood he immediately resolved upon a memorial to his parents, to be located in the city in which he had grown to manhood. The result was Lincoln’s largest park. His boyhood friend—George Woods—picked out the 600 acre site and Mr. Harris came to Lincoln and approved. He was urged to use the family name for the park, but when he visited the site of his old home at 16th and K and stood at the graves of his parents in Wyuka, he decided on another—one which would name his parents in a broader sense and include all these with whom they had toiled in the wilderness—Pioneers.

George Harris, the father, came to Lincoln in the early seventies as land commissioner for the Burlington, and as part of his work brought thousands of people to the state. Later one of the sons, George B. Harris, became president of the Burlington. John F. Harris went to New York and became a successful financier. It was Mr. Harris’ wish not to drive nature from the rolling stretch of prairie presented to Lincoln, only to help her turn her most hospitable face to the city. One of the hills forms a natural amphitheater from which many programs and services have been heard. Lakes beautify the rolling surface of the park. Herds of buffalo and elk are a reminder of the early days. Near the east entrance stands a buffalo in bronze, also given by Mr. Harris, and made in Paris by the famous sculptor, George Gaudet.

The east entrance of Pioneers is guarded by a bronze buffalo, symbol of the prairie when creatures of the plains drifted over her face scarcely aware of the existence of human beings. Their cries, their calls, were for themselves and the seasons. Yet they were not entirely alone. In and out of their orbit moved the Indian, as drifting as were the birds and the beasts. One day he might spread his camp in a valley, the smoke of his campfire lifting to the heavens. In a month, perhaps, he was beyond the horizon. The grasses rose slowly again and possession of the earth came back to the buffalo and the deer, the coyotes and the meadow larks.

Then came the white man. An early Lancaster county settler, John S. Gregory, wrote: “I reached the present site of Lincoln toward evening of a warm day in September (1862). No one lived there, or had ever lived there previous to that date. Herds of beautiful antelope gamboled over its surface during the day and coyotes and wolves held possession during the night.... About a mile west on Middle creek the smoke was rising from a camp of Otoe Indians, and down in the bend of Oak creek, where West Lincoln now stands, was a camp of about 100 Pawnee wigwams. I rode over, and that night slept upon my blanket by the side of one of them.”

The placing of “The Smoke Signal” (by Ellis Burman) in Pioneers was a suitable gesture. Its unveiling and dedication in 1935 was a picturesque, even dramatic, occasion. More than 100 Indians attended the ceremony. Chiefs of four Indian tribes which had roamed Nebraska sat their horses thruout the dedication, grouped at the top of the rugged hill which faces the west and the setting sun.

Antelope park rambles loose-jointedly from the old federal treasury columns at 24th and O south to Sheridan boulevard. It can be and is many things to many people. Here families spread their fried chicken for a blue canopied feast, here the children point their toes to the sky as they pump up swings, here the band begins to play—evening and Sunday concerts. Here the young people dance the evening hours away, the summer Indians brandish their tennis rackets, the flower lovers stroll and gaze at elaborately laid out beds of flowers.

Or, calling all ages, there is the zoological building on south 27th, where the monkeys chatter and swing, the tigers shake their bars and little creatures of all kinds peer out from their cages. Central in the zoo is the scene above. Photographed thru the screen which surrounds it, it has the dreamlike quality of a Chinese painting. Some of the birds took to cover with the appearance of a camera. The scarlet ibis clings morosely to a branch and an African crane, with seedy headgear, is in picturesque tete-a-tete with another exotic bird in the foreground. The stork, to the left, legging its way as usual on the heights, is obliterated except for a beak and bit of curved wing.

The peace of this scene, with its pool, its rocks and flashes of bright color, is seldom disturbed. When the keeper circles the ledge symmetrically with dishes of bananas and grain the birds, big and small, float noiselessly down and begin pecking at their food in genteel manner.

Tucked here and there thruout Antelope park’s pleasant spaces—179 acres—are a number of statues and memorials, results of various impulses and circumstances. We have mentioned the pillars at the O street entrance. Roaming southward thru the park you will find others. One of these objects is the fountain given to the city by the late D. E. Thompson thirty or so years ago. It was placed in the center of 11th street a few blocks south of O. As Lincoln’s herd of automobiles grew to thundering proportions city officials realized that the fountain, very suitable in the days when ladies nodded to each other across it from phaetons and victorias moving on either side, must be transplanted. After a number of accidents, some of them truly tragic, the fountain was taken to the park. Neptune, on one side, had been permanently crippled and the water nymph on the other was doubtless aged in spirit.

In 1936 the Lincoln park department sponsored the putting up of a war memorial—a marble 23-foot shaft topped by a figure in ancient armour—spirit of war and victory. On four lower pedestals Revolutionary, Civil war, Spanish-American and World war soldiers look out, each leaning on his instrument of death. When Mr. Burman and the park department planned this statue they probably had no thought that it would be so quickly outmoded. No niche has been provided for a warrior of the present conflict.

Another figure in the park is The Pioneer Woman, donated by the Woman’s club and the park board. The trees along Memory garden and Memorial drive—north of Sheridan boulevard—were planted in memory of the Lincoln soldiers who fell in the first World war.

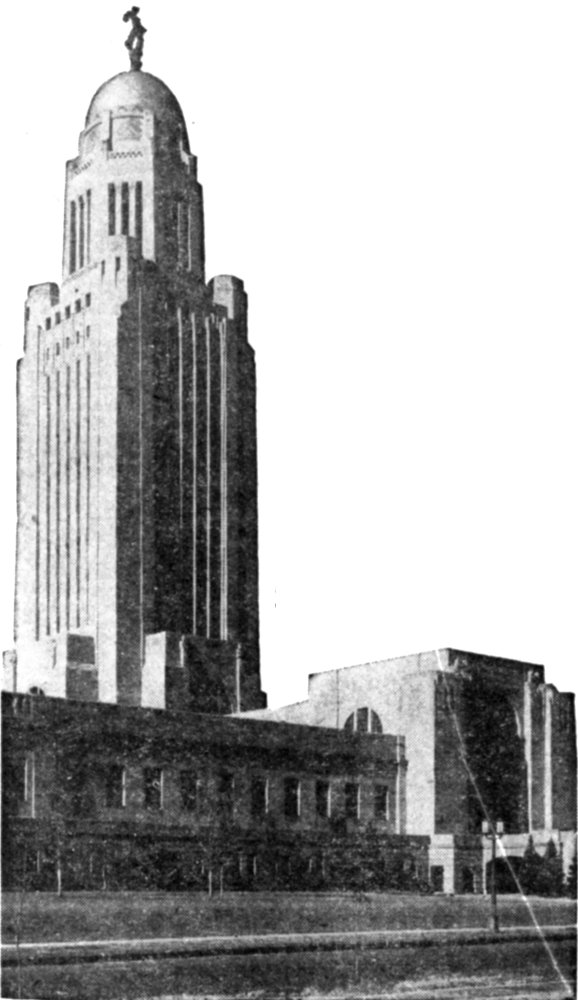

Nebraska’s capitol, designed by Bertram Goodhue, is one of the beautiful buildings of the world. Twenty years ago, disputatious words were circling round its budding tower—derogatory, complimentary, acrimonious, laudatory. But the capitol rose silently thru this swarm of words and today stands superbly in completed perfection. Controversy has died away, and there are probably few Nebraskans who are not proud of the capitol’s majesty and timeless beauty.

Opening a forgotten drawer recently we came upon the dusty drawings of Mr. Goodhue’s rivals in the capitol competition of more than twenty years ago and found them yawn-provoking. Only the one chosen seemed alive, rising into the sky, even on its yellowed paper background, as tho from some inner compulsion.

The capitol has many moods. Sometimes she wraps a dark cloak somberly about her. The next time one turns to look, she shimmers in a cloak of light. The capitol is beautiful in all her moments—silhouetted against the blue, against storm or twilight, or against the limitless background of night.

The inspiration for the capitol as a whole was Bertram Goodhue’s. He first ran an architect’s pencil around its noble contours, in a moment of exaltation flinging its tower toward to stars. But death drew the pencil from his hand while many markings were yet to be made.

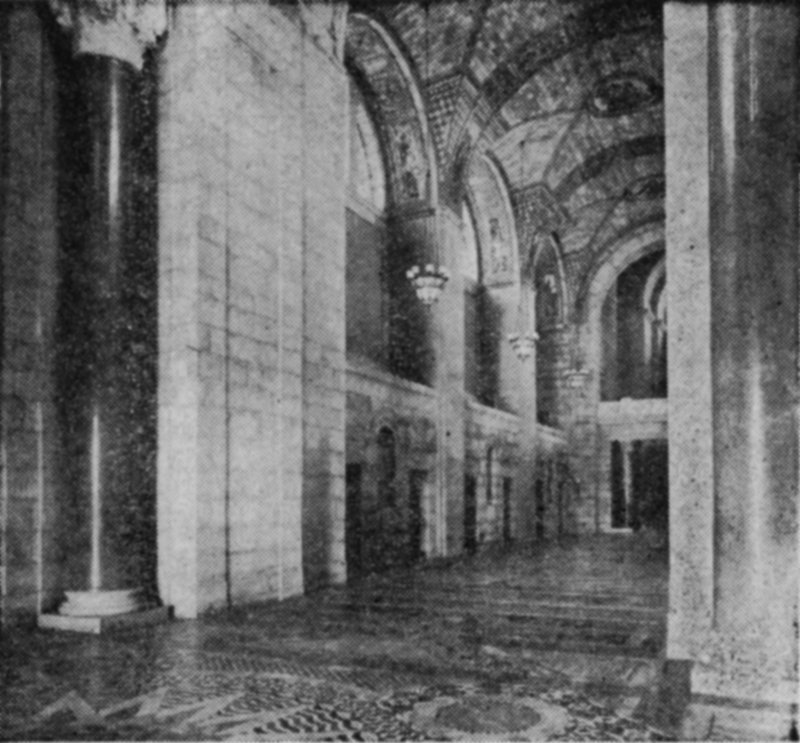

It is said that for no other building since the middle ages has such a definite, complete and comprehensive symbolic scheme been worked out—giving complete unity to the finished edifice. To Mr. Goodhue’s immediate associates, of course, goes a great deal of the credit for the capitol. William Younkin has been the supervising architect. Among others who had a large part in the perfecting of the building are Lee Lawrie, the sculptor, Hildreth Meiere, responsible for its mosaics, and Hartley Burr Alexander, who planned the sculpture, wrote the inscriptions and worked out the art symbolism.

The late Dr. Alexander, native of Lincoln and professor of philosophy at the University of Nebraska until he went to Scripps college in 1927, was familiar to two generations of students in Lincoln. A mild retiring person with a furiously intellectual brow, he possessed great ability in the field of poetry and philosophy, writing perhaps twenty books on these subjects. The inscriptions of the building read unhurriedly along its vast corridors, beginning with the hymn of the Navajo, imprinted on the buffalo at the north entrance: “In Beauty I walk. With Beauty before me I walk. With Beauty behind me I walk, with Beauty above and about me I walk.”

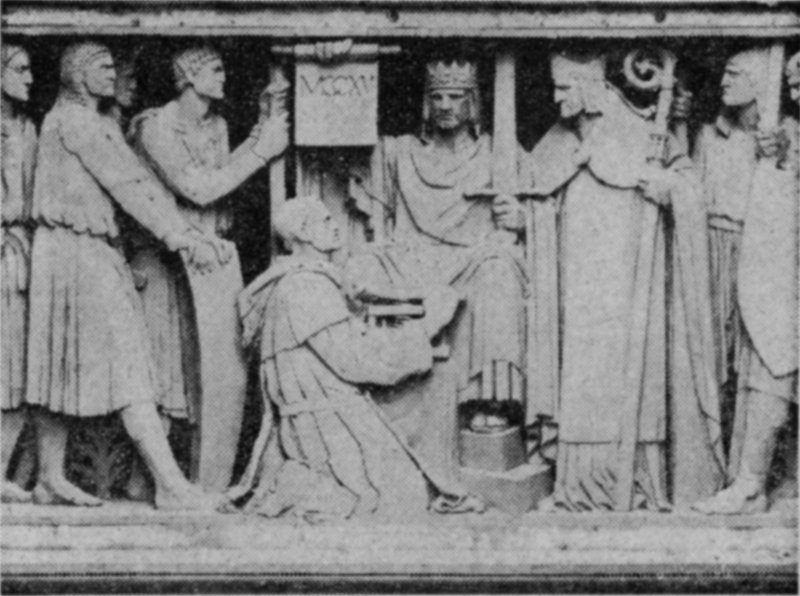

The capitol is the story, in marble, of mankind. Its physical outlines suggest this—sprawling inarticulate humanity drawn up finally into strength and beauty. To amplify the story in words would mean great book piled on great book. For every mosaic, every panel and every rising pillar holds the tale of some great struggle or advance in the life of man. At last the story is brought down to Nebraska—its pioneers, its buffalo, its Indians, its corn and wheat. But before Nebraska comes the whole great panorama of mankind. The upward struggle toward a high ethical code, toward religion, is pictured in great movements or incidents of history.

The western group of nine panels seen from the promenade describes the development of law in the ancient world: Moses bringing the law to Mount Sinai; Deborah judging Israel; judgment of Solomon; Solon giving a new constitution to the Athenians, publishing of the law of the twelve tables in Rome; establishment of the tribunate of the people; Plato writing his dialog on the ideal republic; Orestes before the Areopagites; codification of Roman law under Justinian. On the south wall of the promenade are panels showing the magna carta, signing of the declaration of independence and writing of the constitution. The eastern group describes development of law in the modern and western world, panels including codification of Anglo-Saxon law, Milton defending free speech, signing of the Pilgrim compact, Lincoln’s emancipation proclamation, the Kansas-Nebraska bill and admission of Nebraska as a state.

At the upper corners of the tower eight sculptured figures represent spiritual leaders of civilization, including the prophet Ezekiel, Socrates, Marcus Aurelius, St. John, St. Louis, Isaac Newton and Abraham Lincoln. Abstract virtues, Wisdom, Justice, Power, Mercy are represented as human figures at the north entrance.

Today we shall give you a few facts which include figures—the latter of which we have hitherto dealt out very stingily.

The lower part of the capitol is a square base, 437 feet each way, which conceals four inner courts formally landscaped. The tower reaches into the air 400 feet. The figure of the sower at the top is 20 feet tall and stands on a 12-foot pedestal—a shock of corn on a sheaf of wheat. The sower weighs about nine tons.

The four light colored pillars in the foyer are the largest single piece marble columns in this country. They weigh approximately sixteen tons each. The chandelier which hangs in the center of the building, is the largest bronze chandelier of its type in the world. Its bell part is a single piece of pure bronze, cast in New York City. The whole chandelier weighs 3,500 pounds. It is 112 feet from the floor to the ceiling from which the chandelier depends.

Gov. Samuel McKelvie broke ground for the new building April 15, 1922, with Marshal Joffre of France as guest of honor. Dedicatory exercises were held ten years later. The building cost $10,000,000 and is paid for.

Guides who tell many interesting facts about the capitol make daily trips thru the building, at 10:30, 2:00 and 3:30, excepting that on Sunday the 10:30 tour is omitted.

In 1863 Elder Young founded the town of Lancaster—to become Lincoln four years later—on his own 80 acre tract, which cornered Luke Lavender’s farm at what is now 14th and O. The village was to extend from 14th to 7th and from O to Vine. As the far-sighted elder bent musingly over the white paper which represented the future town he saw a city strong in church life—and even predicted that it would some day be the capital of Nebraska. Another dream was of a female seminary—either to induce families with young ladies to come to the new town or to make prairie damsels into suitable wives and mothers for his churchly city. Hovering over the platted town his pencil finally came to rest at 9th and P as a site for the seminary.

Many of the lots into which his farm was ribboned he gave to county and school districts. Money from the others went into the seminary. That institution burned in 1867, but Elder Young’s dream of a city of churches was more enduring. Between 1866 and 1870 Congregational, Methodist, Presbyterian, Christian, Baptist and Catholic churches were organized and built. These were forerunners of present downtown churches. Lincoln now has about 80 places of worship.

The First Presbyterian church was organized April 4, 1869. Its first two buildings were supplanted in 1927 by the present beautiful structure, one of whose distinctions is having been planned by the late Ralph Adams Crams. Thus may it lay claim to special brotherhood with the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and St. Thomas’ church of New York City.

On July 4, 1870, while Lincoln citizens were celebrating the nation’s birthday in shady groves, as was their wont, there came from the northeast a strange cavalcade. It was a string of flatcars, over which bowers of cottonwood branches had been arranged, pulled by a chortling little engine named The Wahoo, which name probably echoed the cries of the tugging engine rather exactly. Under the bowers sat travelers on improvised seats, chatting excitedly. It was the first passenger train to pull into, or almost into, Lincoln. The Burlington and Missouri rails had been laid to within a mile of the town and the company celebrated by offering a free round trip from Plattsmouth to Lincoln, which was made at the exhilarating speed of 15 or 20 miles an hour.

Within the year George B. Harris became Burlington land commissioner and began colonizing Nebraska on a grand scale. In 1870 Nebraska had 122,993 inhabitants, and most of them lived in the southeastern counties near the Burlington’s 2,500,000 acres. The success or failure of the Burlington’s land department depended largely on price and credit policies adopted by the company. Mr. Harris was given a free hand. Boundlessly enthusiastic over the possibilities of the state, he went at the job like one seating himself at a great organ. Towns sprang up wherever his creative fingers strayed. To the west appeared quickly a string of alphabetical stations—Crete, Dorchester, Exeter, Fairmont, Grafton, Harvard, Inland, Juniata, Kennesaw and Lowell. The “Mayflower” colony, “Plymouth” colony, colonies from England and the east were soon grouped over the landscape.

In the middle 80’s the Burlington shops were located at Havelock. Thru the Burlington lines flows the bloodstream of that part of Lincoln. It thrives or grows pale and listless according to the fortunes of its railroad. The shops at this moment are employing 750 men—550 in the mechanical department, 250 in the store. The shops build cars, repair cars, overhaul electrical equipment used on the lines west of Lincoln and overhaul working equipment such as steam shovels and pile drivers for the whole Burlington system.

One leap from the south entrance of the capitol (if he doesn’t mind our accelerating his step in order to capture the attention of the audience) and Gov. Dwight Griswold, in gray suit and fedora, plus black overcoat the last few days, is home. Should he turn on the steps he might read over the capitol entrance one of Dr. Alexander’s carefully considered truths—Political society exists for the sake of noble living.

The house in which Governor Griswold lives, successor to one populist, five democratic and seven republican gubernatorial residents, suggests noble living. It is generously proportioned, deep bosomed, its wide galleries edged with delicately wrought spindles. Memories jostle each other pleasantly in the big house, which is acclimated to sudden changes.

One republican governor and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Sam McKelvie, preferred to live in their home at 140 So. 26th, where indefatigable Mrs. McKelvie threw off lightly, the actual work of caring for 21 rooms, with oil painting and associate editorship of a magazine as pastimes. For the rest, since 1900—before that governors had to look for places to live, too—each governor’s retinue has moved in and fitted itself into its surroundings in its individual way. Mr. Griswold, for instance, hung his grandfather’s sword—its owner fell in ’61—in the front hall and his collection of autographed photographs in the back parlor. Mrs. Griswold marshaled treasured family antiques into the guest room against a background of George Washington-Mount Vernon wallpaper.

Every governor’s wife handles with pleased fingers the beautiful silver service with the aid of which light refreshments were once dispensed on the battleship Nebraska. During legislative sessions especially, the governor’s home is opened for many social gatherings.

If you drive in a long slow arc from southernmost to northernmost Lincoln, veering to the right as you drive, you will pass thru the parts of the city which were not the result of growth of the original town but sprang up a distance away from some special urge or circumstance. There were five of them, like the isolated fingertip prints of a cupped hand. As Lincoln spread the tiny towns spread also, until they finally all met, embraced and became one.

Driving from one to the other thru these originally diverse sections we feel subtle changes. It may be that thoughts and processes, personalities of those once dominating each, are in some way imprinted on each section. Or it may be only that we happen to know local history. To the south is College View, its nucleus Union college (Seventh Day Adventist). Next in the arc is Bethany, originally the background of Cotner college (Christian) and next its sister, University Place, home of Nebraska Wesleyan (Methodist.); Havelock, a little to the north, was born of the Burlington shops. Last in the arc is Belmont, planned as a beautiful city 50 years ago but now fallen from that high estate. Its woolen mills burned down, the railroad came in the wrong way.

Above is the ivy covered main building of Wesleyan, an institution which has stood sturdily for over 50 years, battling drouths and depressions with one hand and serving the Lord and Methodism with the other. Attesting the educational soundness of its program was a recent national survey showing Wesleyan with a rank of 22 among 339 liberal arts college in the proportion (36 percent) of its students going into graduate study thruout the country. A greater proportion of graduates has gone from its classrooms into theological seminaries than from any liberal arts college in America.

When we downtown Lincoln lunchers gathered in groups at the board on Sept. 17, 1930, we did not begin talking about the stock market or fall fashions or unemployment or our neighbors or any of those things which usually occupied our attention.

Even before reaching for the menu or the sugar bowl everyone burst out with one identical topic—what had happened that morning at 1144 O. We had heard remotely about gangsters and underworld affairs, but on this fair September morning hands from that other world actually reached out and touched quiet respectable Lincoln.

There were submachine guns but no killing. Three men quietly entered the lobby of the Lincoln National bank, with a word turned employes and customers face downward on the floor, scooped up currency, looted a vault and were out again—into a waiting sedan and away. One of the largest bank robberies ever to occur in America—$2,000,000 in currency and bonds—it forced liquidation and closing of the bank.

Gus Winkler, big time gangster and member of Al Capone’s gang, confessed to knowledge of the stolen bonds but established an alibi so far as active participation was concerned. Tommy O’Connor and Howard (Pop) Lee were tried and given long term prison sentences. Jack Britt was released after two trials. Winkler offered to return $600,000 of the securities in return for his freedom. After much discussion and comment on the advisability of such action Winkler won the point. Bonds valued at $575,000 were eventually returned. (Their return, Mr. Towle reminds us, saved five small banks in Lancaster county.) In 1933 underworld enemies caught up with Winkler and he went down fatally wounded by machine gun fire.

From the First-Plymouth tower, music floats out and soars upward like birds shaken free by the great organ inside, grazing Mark, Matthew, Luke and John at the top of the tower with their golden wings. As one enters the church thru the large forecourt, his pleasant sense of gracious earthly living and worship is heightened by the presence of this heaven-looking tower.

First-Plymouth Congregational church, built in brick, cost half a million dollars, was designed by H. Van Buren Magonigle and has become widely known for its architectural freshness and beauty. A picture of it illustrates “Religious Architecture” in Encyclopedia Britannica.

Among individual items of interest are three stones incorporated into the building: The Bethlehem stone from the birthplace of Christ; Pilgrim stone, gift of Plymouth, England, sailing port of the Mayflower; Martin Luther stone in the base of the tower, taken from the home of the reformer. In the singing tower—traditional name of the carillon harking back to mediaeval times when watchers aloft blew warnings of invaders or flooding of dikes, are the bells, made by the famous carillon builders, John Taylor and Co., of Loughborough, England. The church celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1941. Rev. Raymond A. McConnell is its pastor.

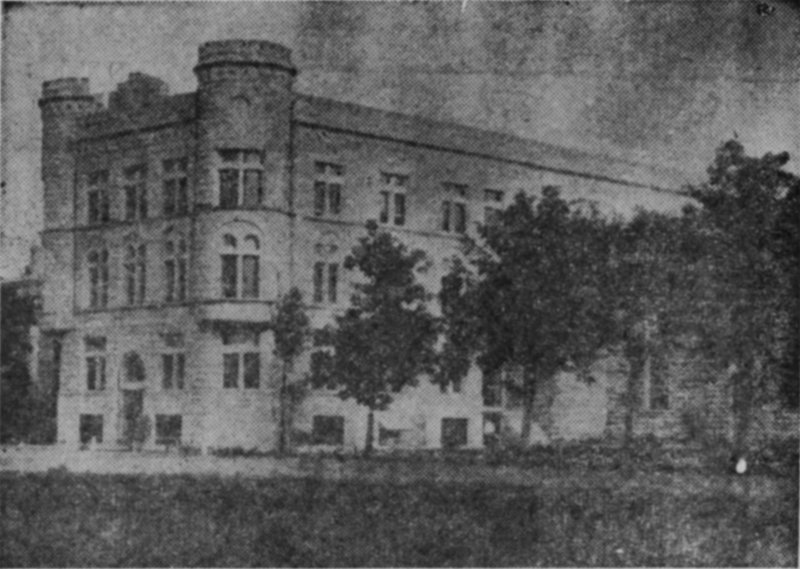

This is Cotner college—Cotner boulevard between Aylsworth and Colby—back, back in the early days of existence. The grass around it appears to be unbroken prairie growth. There are no walks around the building, not even paths. And yet this is very much a picture of Cotner now. After 1889, when the college opened, a tide of green washed up over the campus—a whole grove at the north and big sheltering trees elsewhere. And so also did a tide of youth sweep into the building to give it life. Now both tides have receded. And still, Cotner does not represent a totally lost cause. Young people who wish to attend a denominational college have merely been deflected to other Christian church institutions—Drake, in Iowa, for instance, nearest Nebraska.

A small church college is one of those anomalous places where students in the morning gaze worshipfully upon a preacher professor and in the evening plot to put his cow up in the belfry tower. Scattered over the world as teachers, preachers and missionaries, Cotner students recall happy days here, not only inspirational but full of pranks and fun. The college was named for Samuel Cotner, who donated a large tract of land in Bethany to the school. Closely connected with the school is the name of W. P. Aylsworth, first chancellor and later president emeritus, greatly loved and revered by the procession of students who passed thru the college during his lifetime. He was killed a number of years ago, as twilight was approaching—on Cotner boulevard, named for the college, and near the street named for him—by a speeding driver who did not stop and was never located.

You may have heard that, in case you are absentminded on Saturday, on Sunday morning you can get a loaf of bread or a roast in College View. That is quite true, but such considerations reduce College View to its lowest terms. The fact that most of College View observes its Sabbath on Saturday is the result of a deep religious conviction which set up a college and spread around it a sympathetic community.

Union college (Seventh Day Adventist) has 12 buildings and many interesting features. One of the most interesting is its work program. More than 90 percent of its students, which usually number around 450, pay their way, at least in part, by working on the college farm or in its shops and buildings on the campus.

For the first two-thirds of its lifetime—the college, like Cotner and Wesleyan, was started in the late 80’s—the town was made up exclusively of those of the faith. For longer than that—we are not prepared to say definitely whether or not this is still true—much strictness was observed in the life of the students.

The college now has a medical cadet corps (shown in the picture), part of a nationwide program sponsored by the Seventh Day Adventist denomination and operating under the approval of the surgeon general of the U. S. army.

Early in the nineties, two companions might almost daily be seen on Lincoln’s downtown streets. Written and unwritten history traces their footsteps more minutely—into Don Cameron’s. Curious as to the sort of fame which perpetuated the name of Don Cameron we investigated and found that he was a restaurant keeper. The secret of his popularity and enduring memory seems to have been that he furnished a good meal for 25 cents.