Project Gutenberg's Harper's Round Table, September 22, 1896, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Harper's Round Table, September 22, 1896 Author: Various Release Date: April 29, 2019 [EBook #59387] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, SEPT 22, 1896 *** Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 882. | two dollars a year. |

Little Lady Daffany had just been betrothed to the Prince, and there were great rejoicings all over the town in consequence. The people were allowed to cheer as much as they liked, and every child in the country had a whole holiday and a penny bun, and nobody had an unhappy moment from sunrise to sunset. All the Fairies were invited to a magnificent banquet in the palace that lasted five hours and a half; and the betrothed couple sat at one end of the table, and talked to one another; and the King and Queen sat at the other end, and hoped that everything would go well. The Queen fanned herself, and murmured at intervals. "The wish of my heart"; and the King grumbled to himself because he could not get enough to eat. The King had a very healthy appetite, and he always gave a banquet whenever there was the least occasion for one.

"I really don't think we have left any one out this time," said the Queen, in a satisfied tone. One of the Fairies had been left out at the Prince's christening, and the usual misfortunes had followed in consequence.

"That is because I sent out all the invitations myself," replied the King, crushingly. "These things require only a little management."

The words were hardly out of his royal mouth when a sudden darkness fell upon the room, just as though a curtain had been drawn across the sun. One ray of sun continued to shine, however, and that was the one that shone over Lady Daffany's head; and down this one something[Pg 1134] came sliding at a terrific pace, and tumbled into a dish of peaches just in front of her. The conversation stopped with a jerk, and the people in the street ceased cheering at the same moment, though they could not have told any one why they did not go on.

"I am going to faint!" the Queen was heard to exclaim; but no one was sufficiently unoccupied to attend to her. The eyes of every one were fixed on the one ray of sunlight that shone over Lady Daffany's head into the dish of peaches on the table.

"Now that's a stupid place to keep peaches," said the cause of all this disturbance; and the funniest little man imaginable clambered out of the dish of peaches and looked inquisitively down the long table. He was very small and of a misty appearance, and he was dressed from head to foot in dull yellow fog, and his face was brimful of mischief. He looked as though he had done nothing all his life but make fun of people; for he had very small eyes that twinkled, and a very large mouth that smiled, and the rest of his face was one mass of laughter wrinkles.

"So you thought you were going to leave the Wymps out, did you?" he said, sitting down comfortably on the edge of a large salt-cellar, and swinging his legs backwards and forwards. "You will say you never heard of the Wymps next, I suppose!"

That was just what every one in the room was thinking, but no one had the courage to say so.

"To be sure! to be sure! How stupid of us not to recognize you at once!" said the Queen, who had not fainted, after all.

"Most absurd! Why, the children in the schools could have told us that, eh?" added the King, glancing at the Royal Professor of Geography, who sat on his right hand.

"No doubt; no doubt. Though it does not belong to my branch of learning," said the latter, looking cheerfully at the Royal Professor of History, who was trying, for his part, not to look at anybody at all.

"Then if you know such a lot about us, how was it you didn't ask us to the banquet, eh?" shouted the little Wymp in a most disagreeable manner.

"Dear me!" said the Queen. "Is it possible you never had the letter?"

"I have no doubt," added the King, "that it was never posted."

"Or perhaps it was not properly addressed," suggested Lady Daffany, politely.

The Wymp looked from one to the other and winked; then he stood on his head and burst into a fit of laughter.

"It is no use, dearest," said the Prince, gloomily. "We have never heard of the Wymps, and we had better own it at once. I suppose that means another bad gift, and I had quite enough of that at my christening. It is enough to set one against banquets altogether. There's always some one left out. First, it's Fairies, then it's Wymps. Now, then, Mr. Wymp, just tells us where you came from, and why you are here, and get it over, will you?"

"Now that's sensible. I think I'll shake hands with you," said the Wymp, coming down on his feet again, and standing on tiptoe to grasp the Prince's hand. The Prince felt it was like shaking hands with a very damp sponge.

"Now I'll tell you what it is," continued the Wymp, climbing up a decanter, and standing with one foot on the stopper and the other tucked up like a stork's; "the Wymps have been left out of this banquet altogether, and Wymps are not people to be trifled with. Why people make such a fuss about Fairies I never can make out. Now if you'd left some of them out, it wouldn't have made any difference. They just overcrowd everything, and it's not fair."

The Fairies fluttered their wings indignantly at this, but the Fairy Queen reminded them that it was not polite to make a quarrel in somebody else's house, and the Wymp went on undisturbed.

"So I have come down from the land of the Wymps, which is at the back of the sun, just to remind you that you mustn't leave us out again. However, I see I am spoiling the fun, so I will be off again. But I may as well mention"—here he looked straight at the Prince and burst out laughing again—"that in future you will always tell people what you think of them. Ha! ha! ha! that is the Wymps' gift to you. Good-by!"

And away he sped up the sunbeam again, and the curtain fell away from the sun, and the people in the street went on cheering just where they had left off, and the conversation broke out again at the very place it had been interrupted, and no one would have thought that anything had happened at all. But the Prince heard nothing but the Wymp's mocking laughter, and he sat silent for the rest of the day.

"Are you ill, dear Prince?" asked the Queen.

"Of course not! You are a tiresome old fidget," said the Prince, crossly. Now the Prince was noted for his excellent manners; he was even known to speak politely to his horse and his spaniel; so when the courtiers heard his reply to the Queen, they began to whisper among themselves, and the guests made ready to depart.

"It is the heat; you must really excuse him," said the King, getting up from the table with a sigh.

"What nonsense!" said the Prince. "It is not hot at all. It is your fault for having such a stupid long banquet."

"We have enjoyed ourselves so much," said the guests, as they filed past him.

"Oh no, you haven't," retorted the Prince; "you have been thoroughly bored the whole time, and so have I."

"It is the Wymps' gift," whispered the courtiers.

Two large unshed tears stood in Lady Daffany's eyes when she bade the Prince good-night.

"Do you think I have been bored the whole evening?" she asked him, softly.

"No, dearest," said the Prince, kissing her white fingers; "for you have been with me all the time."

And that, of course, was the truth, so she went away happy.

The days rolled on, and everybody began to wonder at the change in the Prince. He had always been considered the most charming Prince in the world, but now he had suddenly become one of the most unpleasant. He told people of their faults whenever they were introduced to him, and although he was generally right, they did not like it at all. He said the Royal Professor of Geography was a bore, and although no one in the kingdom could deny it, the Royal Professor of Geography naturally felt annoyed. At the state ball he told the King he could not dance a bit, and though the King's partners certainly thought so too, that did not make it any better. But when he told the Queen, in the presence of the Royal Professor of History, that her hair was turning gray under her crown, the Queen said it was quite time something was done.

"The dear fellow cannot be right in his head," she said; "he must have a doctor."

So the Royal Physician was sent for, and he came in his coach-and-four and looked at the Prince; and he coughed a good deal, and said he must certainly have a change of air.

"The Royal Physician always knows," said the Queen.

"But what is the matter with me?" asked the Prince.

"That," said the Royal Physician, coughing again, "is too deep a matter for me to go into just now. In fact—"

"In fact, you don't know a bit, do you?" said the Prince; and he burst out laughing just as unpleasantly as the Wymp had done when he stood on his head.

So the Royal Physician drove away again in his coach-and-four, and the Prince went on telling people exactly what he thought of them. The only person to whom he was not rude was the little Lady Daffany, for he thought nothing but nice things about her, and therefore he had nothing but nice things to say to her. But for all that, she was most unhappy, for she could not bear hearing that other people disliked the Prince; and all the people were beginning to dislike him very much indeed. So one day she slipped out of her father's house quite early in the morning, and went into the wood at the end of the garden. Now she was so kind to all the animals and flowers, that the Fairies had given her the power of understanding their language; so she went straight to her favorite squirrel, who lived in a beech-tree in the middle of the wood, and she told him all about the Prince and the Wymps' gift.[Pg 1135] The squirrel stopped eating nuts, and ran after his tail for a few moments without speaking. Then he winked his eye at her very knowingly, and nodded his smart little head several times, and spoke at last in a tone of great wisdom.

"You must go to the Wymps and intercede for the Prince," he said, and cracked another nut.

"But would they listen to me?" asked Lady Daffany, doubtfully.

"Go and try," said the squirrel. "The Wymps are not bad little fellows, really. They like making fun of people, that's all; and they saw the Prince was a bit of a prig, so they thought they would give him a lesson, don't you see?"

"Perhaps they will think I am a prig too," said Lady Daffany, sadly.

"My dear little lady," laughed the squirrel, "the Wymps never make fun of people like you. Just you go and find the biggest sunbeam you can, and climb up it until you come to the land of the Wymps at the back of the sun. Only you must go with bare feet and with nothing on your head. Now be off with you; I want to finish my breakfast."

The biggest sunbeam she could find was the one that came in at the library window and sent her father, the Count, to sleep over the state documents. And there she took off her little red shoes and stockings, and pulled the golden pins out of her hair, and let it fall loosely round her shoulders, and she began to climb slowly up the ray of sunlight. At first it was very hard work, for it was very slippery, and she was frightened of falling off; but she thought of the Prince, and went on as bravely as she could. And then it seemed as though invisible hands came and helped her upwards, for after that it was quite easy, and she glided up higher and higher and higher until she came to the sun itself—the big round sun. And she went straight through the sun, just as though it were a paper hoop at the circus, and she tumbled out on the other side into a land of yellow fog. There was no sunshine there, and no moon, and no stars, and no daylight—nothing but a dull red glow over everything, like the light of a lamp.

"Why," said Lady Daffany, feeling her clothes to see if they were singed, "I always thought the sun was hot!"

"I have no doubt you did; it is quite absurd what mistakes are made about the sun," said a familiar voice, and, looking round, she saw the identical Wymp who had come to disturb the betrothal banquet.

"Hullo! I've been expecting you," he said, as he recognized her. "Why didn't you come before?"

"Because you didn't send me an invitation," said Lady Daffany, merrily; and she made him a court bow. Now it is true that the Wymps spend their lives in laughing at other people, but they are not accustomed to being laughed at themselves; so when Lady Daffany continued to be amused at her own joke the Wymp drew himself up very stiffly and looked offended.

"I don't see anything whatever to laugh at," he said, severely, "and you had better come along and explain to the King why you've come."

Then he led her through the dimly lighted land of yellow fog, and they passed crowds of other little Wymps who were all so like himself that it was difficult to tell one from another; for they were all dull yellow and misty in appearance, and they all had small eyes and large mouths, and their faces were all covered with laughter wrinkles. They seemed to be spending their time in turning somersaults and tumbling over one another, and laughing loudly at nothing at all. But the Wymp who was with Lady Daffany did not laugh once; he just trotted along in front of her and did not speak a word, so that she really was afraid she had hurt his feelings, and she began to feel sorry.

"Please, Mr. Wymp, I didn't mean to laugh at you at all," she said, very humbly.

"That's all very well," said the Wymp, sulkily, "but no Wymp ever allows any one else to make a joke. Come along to the King."

"But it wasn't a joke!" cried Lady Daffany.

"Oh, well, if it wasn't a joke, that's another matter. Not that I should have called it a joke myself, but I thought you meant it for one," said the Wymp, more cheerfully. "Now why have you come up here at all?"

She hastened to tell him about the Prince, and how much he had been changed by the Wymps' gift, and how she wanted to intercede for him; and her voice grew so sad as she thought about it all that the Wymp had to turn round and shout at her.

"Don't get gloomy," he cried, turning several somersaults in his agitation. "Nobody is ever gloomy in the land of the Wymps. Make another bad joke if you like, but stop being dreary—do."

At this moment they suddenly came upon the Wymp King, who was sitting asleep on his throne all by himself. He was just like the other Wymps, except that he looked too lazy to turn somersaults, and he had no laughter wrinkles at all.

"Is that the King? He doesn't look much like a King," whispered Lady Daffany.

"He hasn't got to look like a King," said the Wymp. "We choose our Kings because they are harmless, and don't want to make jokes, and will keep out of the way. We once had a King who looked like a King—we used to live in the sun then—but he did so much mischief that the sun people turned us out, and we have had to live at the back of the sun ever since."

Lady Daffany felt glad that the kind of King she was accustomed to did look like a King, but she had no time to say so, for just then the Wymp jumped on the throne and woke up the King by shouting in his ear.

"Does any one want anything?" asked the Wymp King, waking up with a jerk, and putting on his crown and his spectacles.

Lady Daffany dropped on her knees in front of the throne and tried not to feel frightened.

"Please, your Majesty—" she began, timidly.

"Who is she talking to?" cried the Wymp King. He had a very gruff voice, through living in a yellow fog all his life; and he spoke so loudly that he completely drowned the rest of her speech.

"Say what you want, and don't give him any titles; he's not used to them," whispered the Wymp.

"Why, I don't believe he is a King at all," said Lady Daffany, standing up again.

"Who says I'm not a King at all?" shouted the Wymp King, angrily.

"If you make any more of your bad jokes, I won't try to help you at all," said the Wymp. "Why don't you say what you want at once?"

So Lady Daffany set to work and told the whole of her story, and begged the Wymp King to take back his fatal gift so that the Prince should no longer tell people what he thought about them until they all came to dislike him.

When she had finished, the King gave a great yawn and took off his crown.

"Doesn't he tell them the truth then?" he asked, sleepily.

"Yes, I—I suppose so," she answered, doubtfully.

"Then why should they mind?" said the Wymp King.

Lady Daffany shook her head. "They do mind," she said.

"Then it's very stupid of them," said the Wymp King, very drowsily. "However, if that's all, the gift can be passed on to you instead. Now go away; I am going to sleep again."

He was already sound asleep, and not another word could be got out of him. Lady Daffany tried not to cry, and turned away.

"I suppose every one will dislike me now," she said, sorrowfully; "but of course that is better than their disliking the Prince."

"Nonsense," said the Wymp, as he led her to the back of the sun; "that would be too good a joke for the King to make. You wait and see. Good-by."

And away she went through the sun again, and came out on the bright side once more, for the sunbeam had moved on since the morning, and then she ran in-doors to find her shoes.

"That's all right," said the Count, putting away the state documents with a great show of relief; "you're just in time for tea. Where have you been all day?"

"I've been for a walk, at least a fly—no, I mean a ride," stammered Lady Daffany. "I'm not quite sure which it was."

"Never mind," chuckled the Count; "I expect you were with the Prince, and didn't notice, eh? Then of course you have heard the wonderful news of the Prince's recovery."

"Then the Wymp did speak the truth!" cried Lady Daffany, clapping her hands for joy.

"What Wymp?" asked the Count. "This has nothing to do with the Wymps. It was a strange physician who came from a far land, and he touched the Prince's tongue, and made him every bit as polite as he used to be. So you can be married at last, and the Prince can go into society again."

"A strange physician?" said his daughter. "I wonder where he has gone now?"

"That's just it," said the Count, pouring out his sixth cup of tea; "he didn't go anywhere. He turned three somersaults down the palace steps, and when they ran to pick him up there wasn't anybody to pick up."

"Then it must have been a Wymp," thought Lady Daffany, and she wandered out into the garden to think it all over.

"I wonder if I have really got the Wymps' gift instead of the Prince," she said to herself. Just then the Prince himself came through the bushes to find her. He no longer looked grave and unhappy, and there was a radiant look on his face.

"Don't you think I have been a very disagreeable Prince lately?" he whispered, as he stooped to kiss her.

"I think you are the dearest Prince in all the world," she answered, softly.

"All the same, the Royal Professor of Geography is an old bore, isn't he?" said the Prince.

"Oh no, I don't think so. He is only clever," answered Lady Daffany.

"But the Queen-Mother's hair is turning gray. Haven't you noticed it?" persisted the Prince.

"I really think you are mistaken, dearest," said Lady Daffany.

And she never found out whether she really had the Wymps' gift or not. But the Prince and the people loved her to the end of her days.

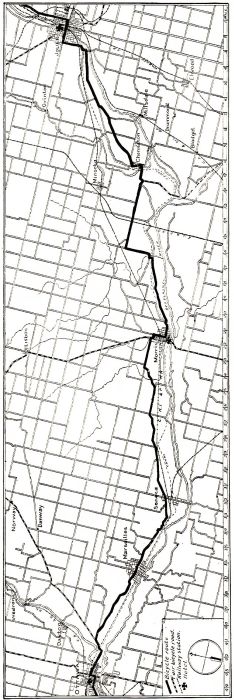

t was at one time supposed that the railroads would be able to carry freight so much cheaper and quicker that the canals would gradually become useless, and only the heaviest and most unimportant class of goods would be sent from place to place over the all-water inland routes. One of the reasons for this was that the canals had not advanced in any way since they were first built—that is, the mechanism of locks had not been improved, and no other methods had been devised by which canal traffic might be made speedier. But about six years ago an American engineer, Mr. Chauncey N. Dutton, invented a lock which many experts think will probably revolutionize canal traffic, and make it possible to build a waterway from New York to the Great Lakes, following the line of the Hudson and using Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River.

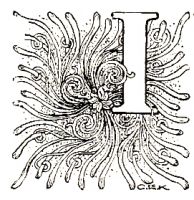

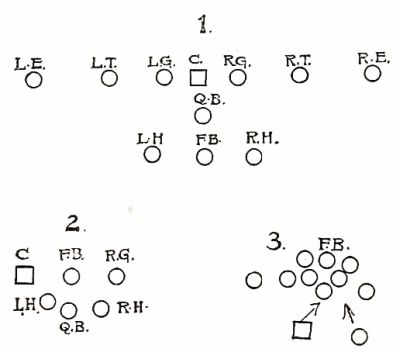

DIAGRAM OF LOCKS.

DIAGRAM OF LOCKS.

The lock invented by Mr. Dutton is founded upon the already well-known and widely utilized principle of compressed air, and although at first it looks complicated to the average person, it is said by mechanics and engineers to be a very simple affair. The lock is called a pneumatic balance lock. It is made up of two sections, each of which may very well be compared to elevators. These elevators are in reality huge tanks, each about 510 feet long, 65 feet wide, and capable of holding 26 feet of water. These tanks are placed in other steel tanks which correspond to the shafts of an elevator, and these shafts are placed alongside of one another. Of course the shafts of these great elevators are sunk as deeply into the earth as it is necessary to raise a ship into the air, or up to the higher level of the canal. The sunken portions of the shafts are filled with water, and the tanks, or elevators, are arranged so that they work up and down like balanced scales—that is, when one is at the higher level the other is at the lower level. Compressed air does all the work. Perhaps by looking at the diagram this may be more clearly made apparent.

The two tanks are connected by a great pipe 21 feet in diameter. Where it connects immediately with the locks this pipe is flexible and moves up and down with the tanks, and looks very much like a huge elephant's trunk. Through it the compressed air shifts, at the will of the operator, from one shaft to the other.

Therefore, supposing one of the tanks is at the highest point of one of the shafts, the other will naturally be at the lowest level of the other shaft. The upper tank is supported by compressed air resting on a body of water which fills the lower portion of the shaft—that is, the part sunken down into the earth. All that it is necessary to do now in order to bring the upper tank or elevator down to the level of the lower tank is to open a valve, and allow the compressed air to run out of one shaft into the other, which it will do at a velocity twenty-eight times that of water. The weight of the descending tank, of course, is the power which forces the air through the pipe from one shaft into the other, and as soon as the two tanks reach the balancing-point they will stop. In order to get the elevator down to the bottom level, therefore, it is necessary to allow[Pg 1137] water to run into that compartment which needs to be made the heavier and to allow water to run out of the other. It is plain to be seen, therefore, that this invention is bound to crowd out the old-fashioned stationary canal lock if it can be constructed cheaply enough.

PNEUMATIC LOCKS IN OPERATION.

PNEUMATIC LOCKS IN OPERATION.

The canal lock of to-day is a very slow working affair, as we all know, and is such a clumsy piece of mechanism that only ships of a limited tonnage can pass through it. When a canal-boat comes along it is let into the first lock, and if that is on the higher level the gates are closed, and the water is allowed to run out until the boat is floating on a level equal to that in the other portion of the lock. Then the gates are opened, and the boat passes on. If it is necessary, on the other hand, to raise the vessel from the lower to the higher level, much more time has to be consumed in order to pump the lock full of water.

By Mr. Dutton's method, however, the vessel comes along the canal, and it may be as large a ship as an ocean freighter, and it may carry as great a cargo as 12,000 tons, and yet it can slip into one of the great steel tanks 510 feet long, and a boy can open the compressed-air valve, and let the great ship travel gently down the elevator shaft until it reaches the lower level of the canal. The operation requires perhaps fifteen minutes, instead of hours; and no more time is necessary for ships of equal tonnage going in the other direction, since a much greater weight of water can be run into the upper tank from the higher level of the canal than could be counterbalanced by any kind of steamship that would need to be lifted from the lower level.

A company has been organized to build a canal from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes, and it is its intention to use Mr. Dutton's locks along the way; not more than two or three will be necessary. But as it will cost about one hundred million dollars to carry out the enterprise, it may be some years before they will be able actually to begin work.

It is the belief of those interested in the construction of this great canal that there is no economy in cheap construction. Good results may only be obtained by good work. The Suez Canal, for example, is cheaply constructed; it is only 72 feet wide at the bottom, and large ships may pass one another only when one goes into a sort of siding, where it usually runs aground. The expense of getting ships out of the sand, since the traffic was first opened through the canal, has far surpassed the sum for which the canal could have been constructed so as to avoid such delays and accidents. Therefore it is proposed that any maritime canal to be built should be fully 250 feet wide, and 30 feet deep at least.

One of the great undertakings which would be connected with the construction of such a canal would be the reversion of the current of Lake Champlain, in order to deepen the water in the upper Hudson. This would be done by diverting a portion of the waters of the St. Lawrence River into Lake Champlain, and such a condition of affairs would develop at Waterford an immense water-power, nearly equal to one-third that of Niagara Falls. This water-power could be used for developing electric-power, and the canal could be illuminated with electric-light at night so as to make traffic almost as easy in the dark hours as in the daytime.

The effects of such an enterprise would be far-reaching. An open-water route from the Atlantic to Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, and Milwaukee would make those great inland cities practically seaports, and therefore the people who live in those cities would be able to purchase all sorts of commodities more cheaply than they can now, because the charges of transportation by water directly from foreign countries would be much cheaper than it is now, when there has to be a transshipment of the goods on the coast, and transportation by rail, which is expensive. On the other hand, the people of those other cities would also be able to sell more of their own products, and to greater advantage to themselves, because they could deliver them in foreign countries more cheaply than they can now.

When the tocsin sounds a rally, over hill and over valley

You will hear a sudden rushing and the tramp of marching feet;

From the lowland to the highland, swift through continent and island,

When the tocsin sends its thrilling call, shall answer willing feet.

For the young folks will be ready, rallying with faces steady,

At the moment when vacation slips with laughing haste away;

Dear old books for weeks neglected will be joyfully collected,

Borne with looks of purest pleasure to the school on opening day.

In the fortress of the mountains, by the gentle falling fountains,

Elves and fays will miss the army late who made the forests ring,

But the school-house will be swarming, teachers' hearts for gladness warming,

When the gallant host is gathered and again the children sing.

Soon will sound for instant rally, over hill and over valley,

That old tocsin which so often we have heard in days of yore,

And with merry faces beaming, to the same dear places streaming,

At a quick-march will the pupils hurry through the school-room door.

"Come into the drawing-room," said Miss Herrick in her most commanding tones.

Valentine and Elizabeth obeyed. They remained standing while she seated herself in the identical carved chair from which so short a time before had dangled the shabby shoes of Eva Louise Brady.

"Who were those children?"

"Eva Louise and Bella Brady," replied her niece.

"And what were they doing here?"

"They—they have been playing jack-stones, and—and eating."

"Eating! Playing jack-stones! And how, may I ask, did they happen to come?"

"We were giving a party, Val and I, especially for the Bradys, Aunt Caroline. I was afraid you might not exactly like it, and so I think if I explain you will understand better."

"It certainly requires an explanation," said Miss Herrick, stiffly. "I suppose that if I had not returned unexpectedly early I should have known nothing of it. I find that you are not to be trusted at all."

"Oh, Aunt Caroline, don't say that! Indeed I am to be trusted; only Val and I—"

"Leave Valentine out of the question. It is you who are responsible."

"But Val thought of it," began Elizabeth, eagerly. "At least he thought of part of it."

Then she stopped. Valentine thus far had said nothing. Was he not going to stand by her? She looked at the boy, but still he remained silent.

"I am waiting for your explanation," said her aunt.

"Well, we saw Eva Louise from the window, and Val said—at least we both thought we would go down and see her. And then on the way I told Val I was so sorry for them, and would like to have a party for them, and he said—at least we both thought it would be very nice to ask them over, and I remembered about that feast in the Bible. Don't you remember, Aunt Caroline, where people are told what kind of parties to give? Perhaps you have never read just that part of the Bible, for you never do give that kind of a party. Your people are all so rich and come in carriages, but it really does say somewhere something about inviting the poor and the lame and the halt and the blind. Well, of course I know the Bradys are poor, and I thought very likely they were halt, and so I decided to ask them."

Miss Herrick was becoming interested in spite of herself. There was something very original about her niece, she thought, and she certainly was beautiful to look at as she stood before her with the earnest look in her great dark eyes, and her high-bred manner of carrying her head.

"Continue," she said, as Elizabeth paused for breath.

"There is not much more to tell except that Val went out and got the things to eat. Of course we had to give them something to eat, Aunt Caroline, and we didn't like to ask the servants."

"And where were the servants all this time?"

"I don't exactly know."

"This must be looked into. I leave you in Marie's charge when Miss Rice is not here."

"I never see much of Marie," remarked Elizabeth, composedly.

"You should have told me of this before. But where did you have the party? In which room?"

Again there was silence. Elizabeth looked once more to Valentine for assistance, but none was forth-coming. A faint color spread over her face and she clasped her hands tightly behind her back, but she gazed steadfastly into her aunt's eyes as she replied, "In the locked room."

"What do you mean?" asked Miss Herrick, not in the least comprehending.

"The locked room in the third-story back buildings. The room with the padlock."

"Elizabeth!"

The child was frightened at the effect of her words. Miss Herrick's face grew very white. It was some minutes before she could control her voice sufficiently to speak.

"Have you been there before?" she asked at last.

"Yes, often," faltered the little girl.

"How did you get in?"

"I—I found the keys one day when I was looking for them in your little Chinese cabinet."

"AND DO YOU CALL THIS AN HONORABLE PROCEEDING?"

"AND DO YOU CALL THIS AN HONORABLE PROCEEDING?"

"And do you call this an honorable proceeding?"

"No, not so very."

If Aunt Caroline would only scold her, thought Elizabeth. She was so calm. The child attempted to excuse herself.

"I had wondered about that room so long, Aunt Caroline. I really did want to know something about my own family, and you and Aunt Rebecca never would tell me. I—I am very sorry."

Miss Herrick did not reply. Presently she turned to Valentine.

"Have you anything to say for yourself?"

"Why, no, not exactly. I didn't really understand about the room. Elizabeth had been there lots of times before I came, and it was her idea about the party in the first place."

"I see," said his aunt, with faint scorn in her voice; "it is merely another case, repeated from time immemorial, of 'the woman tempted me and I did eat.'"

"I don't understand you, Aunt Caroline," said Elizabeth.

But Valentine did understand, and he blushed scarlet.

Miss Herrick, after her last remark, relapsed into thought.

"There is another thing," said Elizabeth, presently; "we broke one of your plates."'

"So we did," said Valentine. Then, with evident effort—"at least, I did. Elizabeth had nothing to do with it. I broke it."

His little sister looked at him gratefully. At last he[Pg 1139] was coming to her rescue. But this final bid of information made small impression on Miss Herrick. She was leaning back in her chair lost in thought.

"Is—is that room still open?" she asked at length.

"Yes, Aunt Caroline."

"Go up and close it; and then, Elizabeth, come to my room. I wish to speak to you alone."

The children, glad to escape, ran up stairs. The door of the room stood wide open, the plates containing the few remnants of the feast were piled recklessly together—everything was in disorder.

They carried the dishes down to the pantry, and put the table back into its accustomed place. They straightened things up as best they could, and then they pulled in the blinds and closed the windows.

Elizabeth locked the door and descended with the keys to her aunt's room. Her party had been a failure from beginning to end. It was very hard for her to keep from crying, but she was determined not to do it—in Valentine's presence, at least.

She found Miss Herrick still in her bonnet. She was standing by the dressing-table, and she held the little cabinet in her hand. She took the keys without a word, put them in the drawer, and shut it with a snap. Then she opened her desk, the key of which she always carried on her person, and placed the cabinet inside.

"I should have done this before," she said. "Is there anything else that you have been prying into?"

Elizabeth's tears refused to be suppressed another moment. She covered her face with her hands.

"I never pry!" she cried. "It was only that one room, and I did so want to know about it. I wouldn't have done it if you had only answered more questions. I have such a stupid time. You won't let me go to school, and you won't tell me anything. And I was all alone, and my father doesn't come home, and I want him—I want him so much! Aunt Caroline"—suddenly drying her eyes and fixing them upon her aunt—"don't you really think my father will come home soon?"

"I doubt if he ever comes home."

"Aunt—Caroline!" Then, after a moment's silence: "But I wrote to him and begged him to come. I said if he couldn't afford it, I would pay for him when I got my money. I really did, Aunt Caroline."

Miss Herrick laughed harshly. She was too much disturbed with the discovery about the closed room to be careful of her niece's feelings.

"Quite unnecessary on your part, Elizabeth. Your father has all the money he needs, and much more. That is not the reason he does not come. I will explain to you, since you are so insistent. I have refrained from doing so before, but I see there is nothing else to do now. Your father left home immediately after the death of your mother. He was deeply attached to her. Your mother, you know, died shortly after you were born, and your father simply could not bear the sight of you."

"Could not bear the sight of me?"

"No. In fact, his one desire was to get away from everybody and everything connected with his former life. He has lived abroad ever since, and I doubt if he ever comes home."

"What will he say when he gets my letter?" asked the child.

"I don't know, I am sure. You ought never to have written that letter. I don't know what he will say."

"Aunt Caroline, would you mind if—if I went up to my room now?"

"Not yet. I have not finished. You deserve a severe punishment for prying into that room, Elizabeth. I have not yet decided what it shall be. Your curiosity must be controlled. What difference need it make to you if forty rooms in the house are locked?"

"I don't know."

"I should think not. That room is connected with the tragedy of my life. I doubt if you ever know about it. Perhaps when you are a woman you may be told of it, but that cannot be decided now. And I ask you never to mention the subject to me again."

"No, Aunt Caroline, I won't."

"You may go now."

"Yes, Aunt Caroline."

Elizabeth walked across the large room to the door. Then she paused a moment, and turning abruptly, she flew back to her aunt's side.

"Aunt Caroline, you said my father could not bear the sight of me when I was a baby. Perhaps I was not a nice baby; some are not—the Brady baby, for instance. Don't you think—don't you really think, Aunt Caroline, that if my father were to meet me now he might like me just a teeny-weeny bit? Is there nothing nice about me, Aunt Caroline? Val, my own brother, likes me. The Brady girls used to like me, only they don't seem to now. I never know whether you and Aunt Rebecca do or not, but I hope you do. But don't you think, Aunt Caroline, dear Aunt Caroline, that if my father ever does come home he might grow to like me a little?"

Her aunt looked at her. Then she stooped and kissed her. "Yes, my dear. Yes, I think he might."

"Then I am going to hope more than ever for him to come. Yes, I am going to pray for it. Every night and morning of my life I am going to ask God to send my father home to me, and I really think, Aunt Caroline, that some day he will come."

And then she went up to her room and cried for an hour.

Valentine returned to Virginia in a few days. He felt sorry for Elizabeth, forced to remain forever in the stiff old house with those stiff old aunts, as he designated them.

"And she is not half bad," he said to himself, as he was being whirled rapidly homeward in the train; "she is really a good sort, though she does get herself into such mighty scrapes. She is a plucky one, though. You don't catch her shirking any of the blame. Well, neither would I with anybody but that dragon of an Aunt Caroline. Elizabeth is more used to her, I suppose."

And then he gave himself up to thoughts of the coming football match, for which he would get home just in time.

With Elizabeth life went on about as usual. She missed Valentine sadly, and she felt almost jealous of her cousin Marjorie, who would always have the pleasure of his society.

Miss Rice was engaged to stay all day now. It was shown to the child plainly enough that she was not to be trusted. She resented this, although she knew there was reason for it. She did hate to be watched, she said to herself.

For months the child brooded over her lonely existence, and the strange fate of having a father who did not wish to see her, and a brother who did not live with her, and who, she was quite sure, preferred his cousin to his sister.

Day after day when the postman rang the door-bell she looked for an answer to her letter, and day after day she was disappointed, until she grew thin and pale, and her aunts at length became alive to the fact that she was not well. Thoroughly alarmed, they sent for the family physician.

He knew something of the state of affairs in Fourth Street, and of the unnatural life which the little girl had thus far lived, and he determined to seize this opportunity for improving matters.

"The child should live in the country," he said, when Elizabeth had been sent from the room.

"Just what I thought," said Miss Herrick, in a relieved tone. "She will go out to our place next week. It is nearly April, so it will not be unbearable."

"But that won't do. Does she have any playmates there?"

"No, not many."

"I thought not. And does her governess go too?"

"Certainly. We could not get along without Miss Rice. My sister and I are away so much."

"Precisely. And now, my dear Miss Herrick, I am going to speak plainly to you. Unless you send that child away she will die before your very eyes. She should be in some happy home where she would have companions of her own age. Boarding-school would be better than nothing. Send her to boarding-school."

"My dear doctor! My niece at a boarding-school? Never!"

"Why not? There are plenty of good schools where she would be happy and well cared for. Then she must go somewhere else. Send her to her mother's relatives in the South. They live in the country, don't they? Let her grow up with Valentine. The brother and sister had much better be together."

"It is out of the question, doctor. I do not want to give up my niece, and I cannot consent to her being brought up in that large family of boys and girls. She would grow very rough among them."

"The rougher the better, say I," said the doctor, rising to go, "and I tell you plainly, Miss Herrick, unless you do something of that sort there is no saving the child. Drugs won't keep her alive. She needs no medicine, but a natural, free child's life, and the sooner you send her to get it the better. She behaves precisely as if she had something on her mind. What is it?"

"I don't know, I am sure," cried Miss Herrick, who was deeply alarmed. "I can't imagine what it is, unless it is about her father. Miss Rice says she talks in her sleep about his not coming home to her."

"And he ought to come home to her," said the doctor, who had been a friend of Edward Herrick's when they were boys. "What right has a man to shirk his responsibilities in this way?"

"Poor Edward!" began Miss Herrick.

"Fudge and fiddlesticks for 'poor Edward'!" exclaimed the doctor, walking about the room. "You have much more reason to say 'poor Elizabeth.' But I had better take myself off before I say anything to be sorry for. Good-morning."

And the front door slammed before Miss Herrick had recovered from her astonishment at his last speech.

She repeated his opinion of Elizabeth to her sister, and then she wrote, though much against her will, to Mrs. Redmond. She could not understand why the life with her father's sisters should not be the best thing in the world for Elizabeth, but apparently it was not.

Several letters passed between Miss Herrick and Mrs. Redmond before matters were finally arranged, and until they were Elizabeth was told nothing. When everything was settled, even to the day and the train by which she was to go, Miss Herrick announced to her that she was to pay a visit of indefinite length to her aunt in Virginia.

"Oh, I don't want to!" exclaimed Elizabeth.

"That makes no difference," returned her aunt. "You must."

"But I won't!" cried the child, stamping her foot. "You have no right to send me away from home."

"Be quiet, Elizabeth! Your temper is becoming quite ungovernable. I hope your aunt Helen will be able to control you."

"She will never have a chance, Aunt Caroline. Rather than go there I will run away from here—I will!"

"Nonsense!" said Miss Herrick, and thought no more of the threat.

Elizabeth left the room, pondering deeply. It would be quite impossible for her to go among strangers, and so far away. Her father might come home any day. She must be at home herself to receive him.

And besides, she could not possibly go to live at her aunt Helen's house, where there were so many boys and girls, among them the incomparable Marjorie of whom Val had spoken so much. Elizabeth remembered all about her, although several months had elapsed since his visit. Her lonely life with its burden of grief and disappointment in regard to her father had told upon her even more than the doctor suspected. She dreaded going among people whom she did not know, and at this distance Valentine also seemed a stranger.

Anything would be preferable to going to Virginia, even life at the Bradys', her only friends.

And this suggested something to her. She would disappear from her home and take refuge with the Brady family. She had read in the newspaper of people disappearing from their homes, therefore it would be quite possible. Life at the Bradys' would not be altogether desirable, but anything was better than being sent away off to Virginia to live with Marjorie.

And if she were at the Bradys' she would be near enough to hear of her father's return, if he ever came. She would ask them to say nothing about her being there, and she would be careful not to go near the back of the house, so there would be no chance of her being discovered, for her aunts would never think of looking for her there.

Her mind was fully made up. She would take refuge with the Brady family.

George's second summer's work was less like a pleasure expedition than his first had been. He spent only a few days at Greenway Court, and then started off, not with a boy companion and old Lance, but with two hardy mountaineers, Gist and Davidson. Gist was a tall, rawboned fellow, perfectly taciturn, but of an amazing physical strength and of hardy courage. Davidson was small but alert, and, in contradistinction to Gist's taciturnity, was an inveterate talker. He had spent many years among the Indians, and, besides knowing them thoroughly, he was master of most of their dialects. Lord Fairfax had these two men in his eye for months as the best companions for George. He was to penetrate much farther into the wilderness, and to come in frequent contact with the Indians, and Lord Fairfax wished and meant that he should be well equipped for it. Billy of course went with him, and Rattler went with Billy, for it had now got to be an accepted thing that Billy would not be separated from his master. A strange instance of Billy's determination in this respect showed itself as soon as the second expedition was arranged. Both George and Lord Fairfax doubted the wisdom of taking the black boy along. When Billy heard of this, he said to George, quite calmly,

"Ef you leave me 'hine you, Marse George, you ain' fin' no Billy when you gits back."

"How is that?" asked George.

"'Kase I gwi' starve myself. I ain' gwi' teck nuttin' to eat, nor a drap o' water—I jes gwi' starve twell I die."

George laughed at this, knowing Billy to be an unconscionable eater ordinarily, and did not for a moment take him in earnest. Billy, however, for some reason understood that he was to be left at Greenway Court. George noticed, two or three days afterwards, that the boy seemed ill, and so weak he could hardly move. He asked about it, and Billy's reply was very prompt.

"I 'ain' eat nuttin' sence I knowed you warn' gwi' teck me wid you, Marse George."

"But," said George, in amazement, "I never said so."

"Is you gwi' teck mo?" persisted Billy.

"I don't know," replied George, puzzled by the boy. "But is it possible you have not eaten anything since the day you asked me about it?"

"Naw, suh," said Billy, coolly. "An' I ain' gwi' eat twell you say I kin go wid you. I done th'ow my vittles to de horgs ev'ry day sence den—an' I gwi' keep it up, ef you doan' lem me go."

George was thunderstruck. Here was a case for discipline, and he was a natural disciplinarian. But where Billy was concerned George had a very weak spot, and he had an uncomfortable feeling that the simple, ignorant, devoted fellow might actually do as he threatened. Therefore he promised, in a very little while, that Billy should not be separated from him—at which Billy got up strength enough to cut the pigeon-wing, and then made a bee-line for the kitchen. George followed him, and nearly had to knock him down to keep him from eating himself ill. Lord Fairfax could not refrain from laughing when George, gravely, and with much ingenuity in putting the best face on Billy's conduct, told of it, and George felt rather hurt at the Earl's laughing; he did not like to be laughed at, and people always laughed at him about Billy, which vexed him exceedingly.

On this summer's journey he first became really familiar[Pg 1142] with the Indians over the mountains. He came across his old acquaintance Black Bear, who showed a most un-Indian-like gratitude. He joined the camp, rather to the alarm of Gist and Davidson, who, as Davidson said, might wake up any morning and find themselves scalped. George, however, permitted Black Bear to remain, and the Indian's subsequent conduct showed the wisdom of this. He told that his father, Tanacharison, the powerful chief, was now inclined to the English, and claimed the credit of converting him. He promised George he would be safe whenever he was anywhere within the influence of Tanacharison.

George devoted his leisure to the study of the Indian dialects, and from Black Bear himself he learned much of the ways and manners and prejudices of the Indians. He spent months in arduous work, and when, on the 1st of October, he returned to Greenway, he had proved himself to be the most capable surveyor Lord Fairfax had ever had.

The Earl, in planning for the next year's work, asked George one day, "But why, my dear George, do you lead this laborious life, when you are the heir of a magnificent property?"

George's face flushed a little.

"One does not relish very much, sir, the idea of coming into property by the death of a person one loves very much, as I love my brother Laurence. And I would rather order my life as if there were no such thing in the world as inheriting Mount Vernon. As it is, I have every privilege there that any one could possibly have, and I hope my brother will live as long as I do to enjoy it."

"That is the natural way that a high-minded young man would regard it; and if your brother had not been sure of your disinterestedness you may be sure he would never have made you his heir. Grasping people seldom, with all their efforts, secure anything from others."

These two yearly visits of George's to Greenway Court—one on his way to the mountains, and the other and longer one when he returned—were the bright times of the year to the Earl. This autumn he determined to accompany George back to Mount Vernon, and also to visit the Fairfaxes at Belvoir. The great coach was furbished up for the journey, the outriders' liveries were brought forth from camphor-chests, and the four roans were harnessed up. George followed the same plan as on his first journey with Lord Fairfax, two years before—driving with him in the coach the first stage of the day, and riding the last stage.

On reaching Mount Vernon, George was distressed to see his brother looking thinner and feebler than ever, and Mrs. Washington was plainly anxious about him. Both were delighted to have him back, as Laurence was quite unable to attend to the vast duties of such a place, and Mrs. Washington had no one but an overseer to rely on. The society of Lord Fairfax, who was peculiarly charming and comforting to persons of a grave temperament, did much for Laurence Washington's spirits. Lord Fairfax had himself suffered, and he realized the futility of wealth and position to console the great sorrows of life.

George spent only a day or two at Mount Vernon, and then made straight for Ferry Farm. His brothers, now three fine tall lads, with their tutor, were full of admiration for the handsome, delightful brother, of whom they saw little, but whose coming was always the most joyful event at Ferry Farm.

George was now nearing his nineteenth birthday, and the graceful, well-made youth had become one of the handsomest men of his day. As Betty stood by him on the hearth-rug the night of his arrival, she looked at him gravely for a long time, and then said:

"George, you are not at all ugly. Indeed, I think you are nearly as handsome as brother Laurence before he was ill."

"NEVER WILL YOU BE HALF SO BEAUTIFUL AS OUR MOTHER."

"NEVER WILL YOU BE HALF SO BEAUTIFUL AS OUR MOTHER."

"Betty," replied George, looking at her critically, "let me return the compliment. You are not unhandsome, but never, never, if you live to be a hundred years old, will you be half so beautiful as our mother."

Madam Washington, standing by them, her slender figure overtopped by their fair young heads, blushed like a girl at this, and told them severely, as a mother should, that beauty counted for but little, either in this world or the next. But in the bottom of her heart the beauty of her two eldest children gave her a keen delight.

Betty was, indeed, a girl of whom any mother might be proud. Like George, she was tall and fair, and had the same indescribable air of distinction. She was now promoted to the dignity of a hoop and a satin petticoat, and her beautiful bright hair was done up in a knot becoming a young lady of sixteen. Although an only daughter, she was quite unspoiled, and her life was a pleasant round of duties and pleasures, with which her mother and her three younger brothers, and above all, her dear George, were all connected. The great events in her life were her visits to Mount Vernon. Her brother and sister there regarded her rather as a daughter than a sister, and for her young sake the old house resumed a little of its former cheerfulness.

George spent several days at Ferry Farm on that visit, and was very happy. His coming was made a kind of holiday. The servants were delighted to see him; and as for Billy, the remarkable series of adventures through which he alleged he had passed made him quite a hero, and caused Uncle Jasper and Aunt Sukey to regard him with pride, as the flower of their flock, instead of the black sheep.

Billy was as fond of eating and as opposed to working as ever, but he now gave himself the airs of a man of the world, supported by his various journeys to Mount Vernon and Greenway Court, and the possession of a scarlet satin waistcoat of George's, which inspired great respect among the other negroes when he put it on. Billy loved to harangue a listening circle of black faces on the glories of Mount Vernon, of which "Marse George" was one day to be King, and Billy was to be Prime Minister.

"You niggers livin' heah on dis heah little truck-patch 'ain' got no notion o' Mount Vernon," said Billy, loftily, one night, to an audience of the house-servants in the "charmber." "De house is as big as de co't-house in Fredericksburg, an' when me an' Marse George gits it we gwi' buil' a gre't piece to it. An' de hosses—Lord, dem hosses! You 'ain' never seen so many hosses sence you been born. An' de coaches—y'all thinks de Earl o' F'yarfax got a mighty fine coach—well, de ve'y oldes' an' po'es' coach at Mount Vernon is a heap finer'n dat ar one o' Marse F'yarfax. An' when me an' Marse George gits Mount Vernon, arter Marse Laurence done daid, we-all is gwine ter have a coach lined wid white satin, same like the Earl o' F'yarfax's bes' weskit, an' de harness o' red morocky, an' solid gol' tires to de wheels. You heah me, niggers? And Marse George, he say—"

"You are the most unconscionable liar I ever knew!" shouted George, in a passion, suddenly appearing behind Billy; "and if ever I hear of your talking about what will happen at Mount Vernon, or even daring to say that it may be mine, I will make you sorry for it, as I am alive."

George was in such a rage that he picked up a hair-brush off the chest of drawers and shied it at Billy, who dodged, and the brush went to smash on the brick hearth. At this the unregenerate Billy burst into a subdued guffaw, and looking into George's angry eyes, chuckled,

"Hi, Marse George, you done bus' yo' ma's h'yar-bresh!" Which showed how much impression "Marse George's" wrath made on Billy.

"I went to the animals' fair,

The birds and beasts were there"—

at any rate it was the animals' hospital, and there were enough birds and beasts for a fair. The hospital is in charge of the New York College of Veterinary Surgeons, and that, if you please, is part of the University of New York; so if you wanted to send your dickey-bird there for the pip, he would be in a manner under the sheltering wing of all the D.D.s and LL.D.s that shine as the regents of that noble institution.

New York people are apt to call this the dog hospital, but that must be because they take more interest in the[Pg 1143] dogs than in its other inmates, for here you can get medical treatment for any living thing except a human being. Horses, cows, dogs, and cats form the steady bulk of its beneficiaries, but elephants and white mice are among them too.

And not only animals are brought here, but the doctors go out and make them professional visits. One of the doctors is now attending the curious dreadful-looking Gila monster at the Zoo in Central Park; he comes—the monster, not the doctor—from Arizona, near the Gila River, and he is two feet long, with a body like an alligator and a head like a snake; he is in a low state of health, and neither food nor drink has passed his lips for seven months. How is that for a poor appetite?

The doctor does not have much hope of him; the matter seems to be that he was kept too warm and fed too much (on raw eggs) last winter, when he ought to have been hibernating, or something like it.

A great deal of the hospital's most interesting practice is among the animals kept in zoological gardens or in travelling shows. An old circus lion was brought here not long ago to have his ulcerated tooth pulled. Now if the toothache makes you feel as "cross as a bear," how cross does the toothache make a live lion feel?

To tell the truth, no one at the hospital wanted to know how cross that lion did feel—they thought it was a case in which it would be folly to be wise. The first thing to be done was to drop nooses of rope on the floor of his cage, and then draw them up when he put his foot in one—he knew he had "put his foot in it" when he found himself snared—and so, step by step, get him bound and helpless. If you will think how particularly hard it is to tie up a cat, you may guess that it is no joke to make a lion fast; he is just like a stupendous cat in his agility and slipperiness. The only way to render him helpless is to get his hind quarters tied up outside his cage, and his head bound fast within it; the next thing, for dental work, is to put a gag in his mouth; that is the easier because there is no trouble at all about getting him to open his mouth—he does it every time any one goes near him.

When they have these beasts of the jungle at the hospital their keepers have to stay with them; but even then they can't always prevent mischief. A baby elephant from a big circus was about the most disorderly patient they ever had there, though, in spite of her naughtiness, she became quite a pet with everybody about. She had a cold and the sniffles when she first came, and was subdued and patient, just like some stirring children when they are sick; but as she got better she almost pulled the whole place down in her efforts to get something to play with. She reached out of her stall and took a large office clock off the wall. No one had supposed she could reach it, and she had broken it to what her keeper called smithereens before he could stop her. If she could find a crack anywhere, destruction began; if it was in the plaster, the plaster was ripped off; if between boards, up came a board. But the baby was not so likely as some of her grown-up relatives to just knock down the side of the house and walk out, which is an occurrence always possible when you have an elephant come to see you. Elephants are poor sailors; they get dreadfully seasick, and often when they are just landed they are brought to the hospital to recuperate. Gin is the great remedy in that case; they particularly love gin, and all their medicine is usually given to them in gin.

When medicine cannot be given disguised in drink or food, it is usually squeezed down the patient's throat with a syringe. The horses are very good about that operation, but the dogs are often troublesome at first; but both dogs and horses soon learn that they are with friends, and then they are wonderfully good and grateful even when the doctors have to hurt them.

For many dogs little can be done until they have been in the institution several days and the doctors have made friends with them; after that they almost always turn out good patients—not always. Do you want to know why some dogs can't be treated there at all? Because they are so homesick; they pine and fret so that their masters, or oftener in these cases it is their mistresses, have to come and take them away, and they must needs have medical attendance at home. One of the most aristocratic patients ever treated here was a French poodle supposed to be worth a thousand dollars. He wore a little diamond bracelet on one paw, and he could do tricks enough to earn his living on the stage; but he did not have to earn his living. He came to the hospital to have his teeth attended to, and some of them were filled with gold. One of his tricks was to laugh, and when he did that all his gold fillings showed.

Many of the pet lap-dogs, particularly those that belong to women, come to the hospital because they have been overfed. The doctors tell a bad story about pugs particularly being little gluttons. On the other hand, they say that many fine and valuable dogs don't get meat enough. Dogs need meat, but some mistaken people think it's better to try to make vegetarians of them, and then the dogs are apt to get the ricketts. The big baby St. Bernards suffer much in this way; it takes a great deal of meat to make a grown St. Bernard out of a young one, and if he does not have enough the job won't be properly done.

The cats and dogs stay in one big ward, each one in its own iron cage, and the cats must understand that the cages are strong, for they don't seem to mind being near the dogs at all. In fact, one of the doctors says he put his own cat in this ward for a while, and when she came home she showed an entire change of heart about dogs; instead of the terror she had always felt of them, she was ready to be good friends with the canine members of her own family. There is a big tin roof railed in that makes an exercising-ground for the convalescent dogs, but the cats have to take the air in a big cage some six feet square that is built on the roof; they can climb too well to be trusted loose.

One of the most cheerful patients in the place now is a canary that has had a leg amputated; he gets on much better than you would if you had only one leg; he chirps, and hops about comfortably, and the doctors think he will soon take to singing again—the brave little bird.

All the appointments of the place are as careful and scientific as they can be anywhere; there are special wards for contagious diseases, and in all operations hands, towels, bandages, and instruments are sterilized after the most approved modern methods. Ether and cocaine are frequently used to save pain, but best of all is the way everybody in the place seems to have a genuine kind feeling, sometimes a warm affection, for the poor yet lucky sufferers.

"Come, stir out of that and get the camels ready for the desert!"

This was Jack's cheery way of warning Ollie and I that it was time to get up on the morning of our start into the sand hills.

"Any simooms in sight?" asked Ollie, by way of reply to Jack's remark.

"Well, I think Old Browny scents one; he has got his nose buried in the sand like a camel," answered Jack.

It was only just coming daylight, but we were agreed that an early start was best. It was another Monday morning, and we knew that it would take three good days' driving to carry us through the sand country. We had learned that, notwithstanding what our visitor of the first night had said, there were several places on the road where we could get water and feed for the horses. We should have to carry some water along, however, and had got two large kegs from Valentine, and filled them and all of our jugs and pails the night before. We also had a good stock of oats and corn, and a big bundle of hay, which we put in the cabin on the bed.

"Just as soon as Old Blacky finds that there is no water along the road he will insist on having about a barrel a[Pg 1144] day," said Jack. "And if he can't get it he will balk and kick the dashboard into kindling-wood."

A little before sunrise we started. It was agreed, owing to the increase in the load and the deep sand, that no one, not even Snoozer, should be allowed to ride in the wagon. If Ollie got tired he was to ride the pony. So we started off, walking beside the wagon, with the pony just behind, as usual, dangling her stirrups, and the abused Snoozer, looking very much hurt at the insult put upon him in being asked to walk, following behind her.

For three or four miles the road was much like that to which we had been accustomed. Then it gradually began to grow sandier. We were following an old trail which ran near the railroad, sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other; and this was the case all the way through the hills. The railroad was new, having been built only a year or two before. There were stations on it every fifteen or twenty miles, with a side track, and a water-tank for the engines, but not much else.

There was no well-marked boundary to the sand hills, but gradually, and almost before we realized it, we found ourselves surrounded by them. We came to a crossing of the railroad, and in a little cut a few rods away we saw the sand drifted over the rails three or four inches deep, precisely like snow.

"Well," said Jack, "I guess we're in the sand hills at last if we've got where it drifts."

"I wonder if they have to have sand-ploughs on their engines?" said Ollie.

"I've heard that they frequently have to stop and shovel it off," answered Jack.

As we got farther among the sand dunes we found them all sizes and shapes, though usually circular, and from fifteen to forty feet high. Of course the surface of this country was very irregular, and there would be places here and there where the grass had obtained a little footing and the sand had not drifted up. There were also some hills which seemed to be independent of the sand piles.

We stopped for noon on a little flat where there was some struggling grass. This flat ran off to the north, and narrowed into a small valley through which in the spring probably a little water flowed. We had finished dinner when we noticed a flock of big birds circling about the little valley, and, on looking closer, saw that some of them were on the ground.

"They are sand-hill cranes," said Jack. "I've seen them in Dakota, but this must be their home."

They were immense birds, white and gray, and with very long legs. Jack took his rifle and tried to creep up on them, but they were too shy, and soared away to the south.

OUR FIRST CAMP IN THE SAND HILLS.

OUR FIRST CAMP IN THE SAND HILLS.

We soon passed the first station on the railroad, called Crookston. The telegraph-operator came out and looked at us, admitted that it was a sandy neighborhood, and went back in. We toiled on without any incident of note during the whole afternoon. Toward night we passed another station, called Georgia, and the man in charge allowed us to fill our kegs from the water-tank. We went on three or four miles and stopped beside the trail, and a hundred yards from the railroad, for the night. The great drifts of sand were all around us, and no desert could have been lonelier. We had a little wood and built a camp fire. The evening was still and there was not a sound. Even the blacksmith's pet, wandering about seeking what he could devour, and finding nothing, made scarcely a sound in the soft sand. The moon was shining, and it was warm as any summer evening. Jack sat on the ground beside the wagon and played the banjo for half an hour. After a while we walked over to the railroad. We could hear a faint rumble, and concluded that a train was approaching.

"Let's wait for it," proposed Jack. "It will be along in a moment."

We waited and listened. Then we distinctly heard the whistle of a locomotive, and the faint roar gradually ceased.

"It's stopped somewhere," I said.

"Don't see what it should stop around here for," said Jack. "Unless to take on a sand-hill crane."

Then we heard it start up, run a short distance, and again stop; this it repeated half a dozen times, and then after a pause it settled down to a long steady roar again.

"It isn't possible, is it, that that train has been stopped at the next station west of here?" I said.

"The next station is Cody, and it's a dozen miles from here," answered Jack. "It doesn't seem as if we could hear it so far, but we'll time it and see."

He looked at his watch and we waited. For a long time the roar kept up, occasionally dying away as the train probably went through a deep cut or behind a hill. It gradually increased in volume, till at last it seemed as if the train must certainly be within a hundred yards. Still it did not appear, and the sound grew louder and louder. But at the end of thirty-five minutes it came around the curve in sight and thundered by, a long freight train, and making more noise, it seemed, than any train ever made before.

"That's where it was," exclaimed Jack. "At Cody, twelve miles from here, and we first heard it, I don't know how far beyond. If I ever go into the telephone business I'll keep away from the sand hills. A man here ought to be able to hold a pleasant chat with a neighbor two miles off, and by speaking up loud ask the postmaster ten miles away if there is any mail for him."

We were off ploughing through the sand again early the next morning. We could not give the horses quite all the water they wanted, but we did the best we could. We were in the heart of the hills all day. There were simply thousands of the great sand drifts in every direction. Buffalo bones half buried were becoming numerous. We saw several coyotes, or prairie wolves, skulking about, but we shot at them without success. We got water at Cody, and pressed on. In the afternoon we sighted some antelope looking cautiously over the crest of a sand billow. Ollie mounted the pony and I took my rifle, and we went after them, while Jack kept on with the wagon. They retreated, and we followed them a mile or more back from the trail, winding among the drifts and attempting to get near enough for a shot. But they were too wary for us. At last we mounted a hill rather higher than the rest, and saw them scampering away a mile or more to the northwest. We were surprised more by something which we saw still on beyond them, and that was a little pond of water deep down between two great ridges of sand.

"I didn't expect to see a lake in this country," said Ollie.

I studied the lay of the land a moment, and said: "I think it's simply a place where the wind has scooped out the sand down below the water-line and it has filled up. The wind has dug a well, that's all. You know the operator at Georgia told us the wells here were shallow—that there's plenty of water down a short distance."

We could see that there was considerable grass and quite an oasis around the pond. But in every other direction there was nothing but sand billows, all scooped out on their northwest sides where the fierce winds of winter had gnawed at them. The afternoon sun was sinking, and every dune cast a dark shadow on the light yellow of the sand, making a great landscape of glaring light covered with black spots. A coyote sat on a buffalo skull on top of the next hill and looked at us. A little owl flitted by and disappeared in one of the shadows.

"This is like being adrift in an open boat," I said to Ollie. "We must hurry on and catch the Rattletrap."

"I'm in the open boat," answered Ollie. "You're just simply swimming about without even a life-preserver on."

We turned and started for the trail. We found it, but we had spent more time in the hills than we realized, and before we had gone far it began to grow dark. We waded on, and at last saw Jack's welcome camp-fire. When we came up we smelled grouse cooking, and he said:

"While you fellows were chasing about and getting lost I gathered in a brace of fat grouse. What you want to do next time is to take along your hat full of oats, and perhaps you can coax the antelope to come up and eat."

The camp was near another railroad station called Eli. We had been gradually working north, and were now not over three or four miles from the Dakota line; but Dakota here consisted of nothing but the immense Sioux Indian Reservation, two or three hundred miles long.

The next morning Jack complained of not feeling well.

"What's the matter, Jack?" I asked.

"Gout," answered Jack, promptly. "I'm too good a cook for myself. I'm going to let you cook for a few days, and give my system a rest."

"HE WOULD SOMETIMES GET HIS RECIPES MIXED UP."

"HE WOULD SOMETIMES GET HIS RECIPES MIXED UP."

This seemed very funny to Ollie and I, who had been eating Jack's cooking for two or three weeks. The fact was that the gouty Jack was the poorest cook that ever looked into a kettle, and he knew it well enough. He could make one thing—pan-cakes—nothing else. They were usually fairly good, though he would sometimes get his recipes mixed up, and use his sour-milk one when the milk was sweet, or his sweet-milk one when it was sour; but we got accustomed to this. Then it was hard to spoil young and tender fried grouse, and the stewed plums had been good, though he had got some hay mixed with them; but the flavor of hay is not bad. We bought frequently of "canned goods" at the stores, and this he could not injure a great deal.

We did not pay much attention to Jack's threat about stopping cooking. He got breakfast after a fashion, mixing sour and sweet milk as an experiment, and though he didn't eat much himself, we did not think he was going to be sick. But after walking a short distance he declared he could go no farther, and climbed into the cabin and rolled upon the bed.

Ollie and I ploughed along with the sand still streaming, like long flaxen hair, off the wagon-wheels as they turned. In a little valley about ten o'clock Ollie shot his first grouse. We saw some more antelope, and met a man with his wife and six children and five dogs and two cows and twelve chickens going east. Ho said he was tired of Nebraska, and was on his way to Illinois. At noon we stopped at Merriman, another railroad station. Jack got up and made a pretense of getting dinner, but he ate nothing himself, and really began to look ill.

We made but a short stop, as we were anxious to get out of the worst of the sand that afternoon. We asked about feed and water for the horses, and were told that we could get both at Irwin, another station fifteen miles ahead. We pressed on, with Jack still in the wagon, but it was dark before we reached the station. We found a man on the railroad track.

"Can we get some feed and water here?" I asked of him.

"Reckon not," answered the man.

"Where can we find the station agent?"

"He's gone up to Gordon, and won't be back till mid-night."

"Hasn't any one got any horse feed for sale?"

"THERE ISN'T A SMELL OF HORSE FEED HERE."

"THERE ISN'T A SMELL OF HORSE FEED HERE."

"There isn't a smell of horse feed here," said the man. "I've got the only well, except the railroad's, but it's 'most dry. I'll give you what water I can, though. As for feed, you'd better go on three miles to Keith's ranch. It's on Lost Creek Flat, and there's lots of hay-stacks there, and you can help yourself. At the ranch-house they will give you other things."

We drove over to the man's house, and got half a pail of water apiece for the horses. They wanted more, but there was no more in the well. The man said we could get everything we wanted at the ranch, and we started on. The horses were tired, but even Old Blacky was quite amiable, and trudged along in the sand without complaint.

Jack was still in the wagon, and we heard nothing of him. It was cloudy and very dark. But the horses kept in the trail, and after, as it seemed to us, we had gone five[Pg 1146] miles, we felt ourselves on firmer ground. Soon we thought we could make out something, perhaps hay-stacks, through the darkness. I sent Ollie on the pony to see what it was. He rode away, and in a moment I heard a great snorting and a stamping of feet, and Ollie's voice calling for me to come. I ran over with the lantern, and found that he had ridden full into a barbed-wire fence around a hay-stack. The pony stood trembling, with the blood flowing from her breast and legs, but the scratches did not seem to be deep.

"We must find that ranch-house," I said to Ollie. "It ought to be near."

For half an hour we wandered among the wilderness of hay-stacks, every one protected by barbed wire. At last we heard a dog barking, followed the sound, and came to the house. The dog was the only live thing at home, and the house was locked.

"Well, what we want is water," I said, "and here's the well."

We let down the bucket and brought up two quarts of mud.

"The man was right," said Ollie. "This is worse than the Sarah Desert."

"Fountains squirt and bands play 'The Old Oaken Bucket' in the Sarah Desert 'longside o' this," I answered.