Bump-Arch had to complete his experiment or spend five more years as an apprentice Scientist—and if successful, his feat would provide plenty of

By Ralph Robin

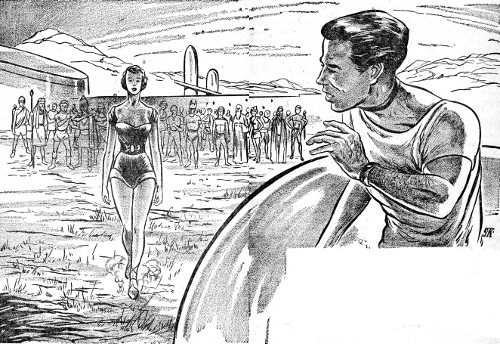

Illustration by Sam Kweskin

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Other Worlds March

1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S.

copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Bump-Arch had to complete his experiment or spend five more years as an apprentice Scientist—and if successful, his feat would provide plenty of

"Time," said the Grandmaster of the Guild.

It was the formal word, and the scientists were silent; except Proudwalk, a biologist, who laughed at something whispered in her ear by a physicist named Snubnose, her brother.

"Time," the Grandmaster repeated, and in a moment even Proudwalk was quiet, and Snubnose folded his arms.

"I do not need to tell you that today is the Day of the Candidate," said the Grandmaster, supporting himself with an air of great age on his ceremonial staff of polished copper.

"But he will tell us—in many words," Snubnose whispered now. "Next winter solstice I am going to propose we double the offering."

Proudwalk sniggered.

It was the practice in the Guild of Scientists that a grandmaster, once elected, served for life or until he voluntarily retired. Every year the body formally offered its grandmaster a lump sum to retire. Popular incumbents were offered one tilsin, an obsolete unit worth less than the smallest real coin. Others were sometimes offered large amounts.

This system did not encourage elderly grandmasters to be laconic.

Unnecessarily consulting his notes, the Grandmaster declaimed, "On this Day of the Candidate, the 155th day of the year 1712, Dynastic Reckoning Corrected—"

Snubnose muttered, "Anybody else would say DRC."

Proudwalk patted his lips. "Hush," she said.

"—we are initiating the consideration of the candidature of Bump-arch apprentice physicist in the service of Crookback, a master physicist beloved and esteemed by us all. The candidature of Bump-arch will be governed by the Principles, by the Laws of the Guild, and by Acknowledged Custom. The procedure—"

While the Grandmaster talked, Snubnose pondered the familiar procedure—and some implications the venerable bore didn't concern himself with.

To become a journeyman scientist, an apprentice had to do two things. He had to complete his term of service. And he had to perform on a Day of the Candidate a successful demonstration in his own branch of the scientific art.

The demonstration always took place on the Field of Proof before the whole body. It could be either an original experiment or a "restored experiment"—one reconstructed from fragments of ancient texts. Standards were low and almost anything was accepted, so long as the candidate accomplished what he said he would. If a conceited or, as occasionally happened, a gifted young man attempted a very complicated demonstration, and it didn't come off—well, it was just too bad.

The unfortunate candidate could either serve another five years of apprenticeship and try again, or give up all connection with the Guild. If he left the Guild of Scientists, he couldn't be admitted in any other Guild.

Which was no laughing matter.

Only journeymen and masters and kingsmen—in the general sense, both men and women—had full rights of citizens, including the right to marry by Public Law. Others might get married by Private Law, but that was a rather uncomfortable method.

Under Private Law, a man and a woman would sign a contract to marry, and if they succeeded in living together—"dwelling under the same roof as husband and wife"—for five years without being discovered by the Public Law police, they could then live together openly. They would then be as legally married as the most respectable members of the Guild of Merchants. But if the Public Law police caught them before the "years of cover" were completed, they were separated and sold as slaves.

Permission of all the parents was required for marriage by Public Law, whatever the age of the lovers. Consequently, even high-ranking guildfolk sometimes took their chances with Private Law, although most who tried it ended their lives threshing rye for the Lords of the West.

For example, Singwell and Gray-eyes....

Snubnose found such thoughts painful. He glanced at his sister and wondered how she could go on looking so cheerful. "But I suppose I look cheerful, myself," he thought. Indeed, he had the kind of face that couldn't look otherwise.

Snubnose followed his sister's eyes to the Candidate's stool; where Bump-arch, Proudwalk's lover and his friend, sat indolently, with his long legs twisted under him.

He wondered what Proudwalk and Bump-arch were going to do.

Certainly they weren't going to get married by Public Law. He winced as he remembered the furious screams of his mother every time Proudwalk brought up the question. Snubnose took his sister's side, but it seemed hopeless to win their mother over. And even if they succeeded, it wouldn't do any good. Bump-arch wasn't going to qualify for journeyman's rank, because he had stubbornly insisted on a demonstration that was sure to fail.

It was a crazy situation, Snubnose thought. Here he himself was a full-fledged journeyman, and here was his sister a full-fledged journeywoman, while a talented fellow like Bump-arch would remain an apprentice or become a guildless outcast. For that difficulty he had nobody to blame but himself, Snubnose reflected, in the virtuous way we meditate upon the mistakes of our friends.

Now the Grandmaster was introducing Crookback, Bump-arch's master, and as late as the previous Day of the Candidate, Snubnose's master as well. Snubnose looked at the old man more affectionately than he had while in his service. But he blamed Crookback for permitting Bump-arch to go ahead with his impossible demonstration. He was puzzled, as usual, by the motives of the old master physicist, born with a bent body and a clever, enigmatic mind.

A few formal words, a brief joke, and a couple of compliments—and Crookback presented the Candidate.

Bump-arch unwound his legs and stood before them. "Elder ones," he began traditionally, and Snubnose thought he caught a quick, impudent look. Bump-arch was young—the three of them were young together in their city and their time—but he was two years older than Snubnose and a year older than Proudwalk. He had started his apprenticeship a little later than was usual.

"I will say the thing. I will attempt the thing. Yours, elder ones, to judge whether the thing is done, whether I am worthy to sit among you." These too were traditional phrases.

"I will construct a chamber," he said casually, "in which I will go irreversibly from today, 155th-1712 DRC, to a day in the future, 155th-1717 DRC. I would be proud to claim this demonstration as my own discovery, but it is not; it is a restored experiment. I follow the directions I copied, while still a boy, from an ancient inscription in a vault outside the walls. The vault was afterward buried by the earthquake."

"And very conveniently too," Snubnose added to himself. Bump-arch had not admitted it, even to him, but Snubnose was convinced that the chamber was his friend's own invention.

"Reverence, elder ones," Bump-arch said and walked to the arched door of the meeting room.

"Time," said the Grandmaster.

Snubnose, rising, heard a conversation behind him, as two master chemists shuffled to their feet.

"Do you think the youngster will do it?" one asked.

"Well, there's a tradition about it," the other said.

"Yes, and there's a tradition about the elixir of life and a hundred texts as well, and you remember what happened to the young fellow who tried to make it."

There was a chuckle. "I remember, and he's not so young any more, and he's the best apprentice I have for washing glassware. Most experience."

Proudwalk had heard the conversation also, and her face turned red. She raised her delicate nose—quite unlike her brother's snub—and sniffed loudly.

"I think I smell hydrogen sulfide," she said.

Carrying his copper staff the Grandmaster paced to the arched doorway, followed by Crookback. Bump-arch bowed as they preceded him through the door; and he had to bend his head again to pass through, for Bump-arch was partly of Bowman stock and tall for a man of the City.

The masters and mistresses of the Guild, the journeymen and journeywomen, filed out behind the Candidate in the order of their seniority. When Proudwalk and her brother reached the Street of the Scientists, already the kingsman and the godsman had taken their places to the right and the left of the Grandmaster in the foremost rank of the procession.

The kingsman wore his second gaudiest uniform—the most splendid was reserved for coronations—and carried his silver mace of authority. The godsman was naked, as above display and free of the temptations of sex. He carried nothing, for his nakedness was his badge of office. It was death for anyone except a godsman or a godswoman to be found in a public place unclothed.

There came next the Candidate and his master, and after them by two's the whole body of scientists. Proudwalk and Snubnose walked together, the last pair.

Early in the morning Snubnose had determined to cheer up his sister as much as he could on this unhappy day. Now she walked along so lightly and smiled so much and so gaily, that it was obvious that she needed no cheering. Snubnose was irritated.

"I don't see why you didn't talk him out of it," he said. "He might have listened to you where he wouldn't listen to me. He has the odd delusion that you're smarter than I."

"I am," said Proudwalk.

Snubnose growled.

He said, "You must not care about him as much as you let on, for all your mooning around the gardens. Well, it doesn't surprise me much. You women are all obsessed with family pride, no matter how liberal you pretend to be. Of course you can't marry Bump-arch, whose mother's father was a Bowman. Our—two to the tenth power—one thousand and twenty-four ancestors, all pure City, all guildfolk from the very best guilds, would disturb every palace in Spiritland with their wailing. So now Bump-arch won't qualify, and it will be an easy out for you."

"Snubnose, you know that's not true. But I'll tell you something." She lowered her voice. "I told Bump-arch not to listen to you and to go ahead with his demonstration."

"But why? Even if you are only a biologist, you ought to know from your basic studies that all the best thinkers in physics for five hundred years have regarded time travel as a physical impossibility and all old traditions of time travel as myths."

"Oh little gods. Whatever we can't do any more is impossible and a myth. We just won't admit we are not as good scientists as our remote ancestors. But some of us are as good, or even better."

"By all the gods, big and little, you really do love the poor fellow. He's good, but not that good. What will you do now? Wait till he finishes another apprenticeship and hope mother changes her mind meanwhile? And then he would probably come up with another impossible demonstration. Listen," he said, whispering in her ear, "if you two are thinking of something crazy like Private Law at least let me know so I can help you. I wish father were alive," he added helplessly.

"So do I. He was the only one in our family with any sense. Thanks just the same, Snubnose," she said, and she pressed his hand.

For a little while he solemnly held her hand, then suddenly dropped it.

"I didn't think," he said. "This is worse than ever. If you really believe that Bump-arch's demonstration is going to work, you don't seem a bit worried about the fact that you won't see him for five years. And another thing," said the young man, "if his physics are right you will be getting old and he will be the same age he is now."

"In five years I'll be an old, old woman," said the girl sarcastically, "and you'll be an old, old man, and we'll sit in the square in the sun and talk about all this. But right now let's quit talking about it, because I see that little Shrill-voice ahead of us there is pricking up her ears."

But she herself said one more thing. "If you're so anxious to worry, worry about the Principles. That's the one thing that is bothering me."

Then they smiled at each other and were silent. And soon a wave of silence washed back to them as the head of the procession turned from the Street of the Scientists, lined with its wind-ruffled oaks, to the open shining Avenue of the Sun, where no person might speak without sacrilege.

The godsman raised his hands to the sun, and everyone else, entering the Avenue, bowed his head.

They marched in silence, formally, humbly, until at the Street of Ward, arms clashed in salute. Here were the apartments of the honorary militia, the warders. The street ran between their dwellings and the city wall. The warders had formed their squads on the flat roofs, and they were happily juggling their polished weapons; more effective for their sparkle and clang, wiseacres said, than for repelling the Bowmen.

During the previous generation, mobile units of the Public Law police had taken over the job of fighting the intermittent wars with the Bowmen. For that reason, as Snubnose knew well, the police would be especially vindictive in tracking down Bump-arch and Proudwalk if they attempted a Private Law marriage. The Public Law police hated anyone with genes of the Bowmen in his chromosomes.

The last squad of warders saluted, and the scientists trooped onto the Field of Proof. It was called in one of the songs of the Guild of Scientists "verdant place where truth doth reign." But the place was only spottily verdant, because the apprentice biologists who were supposed to keep the Field grassed were not conscientious. They spent most of their time in the Ready Hall gossiping with prospective candidates.

Dust rose from large bare patches beneath the copper-tipped shoes of the scientists.

At a sign from the Grandmaster, the guildfolk spread in a single circle. The Grandmaster took his position at the center of the circle with the Candidate, the Candidate's master, the kingsman, and the godsman.

The Bowman strain in Bump-arch was conspicuous, as he stood beside the others. It was marked by his height and by the unmistakable way the bones of his face shaped themselves. A romantic girl could look at him and think of a noble primitive and fall in love, Snubnose reflected. A family-proud dame could look at him and think of the public slaves—Bowmen captured in battle—sweating and stinking in the building gangs.

"What do I think?" Snubnose asked himself. He shrugged. "Bump-arch is my friend."

He turned to say something to his sister, and he saw that she had left him. While the circle had been forming, she had moved a quarter way around. Now her eyes were fixed on her lover.

Snubnose felt vaguely hurt. He said to himself, childishly, "They're up to something, and they're treating me like a little boy again."

"Time," said the Grandmaster.

And what was time? Snubnose, the grown-up physicist, asked himself that question.

In his physics it was the denominator of velocity; squared, the denominator of acceleration. In old texts—incomplete, variously translated, little understood—it was called a dimension when multiplied by an imaginary number. But imaginary numbers had no place in physics. So it had been decided in 1480 DRC, at the historic conference of scientists, kingsmen, and godsmen. Imaginary numbers, with some other concepts, had been declared metaphysics and had been turned over to the godsmen. Just as neuroses, because of their traditional origin in sexual impulses, had been taken away from the psychologists and assigned to the kingsmen.

Snubnose remembered how Crookback had catechized the pair of them, Bump-arch and him, on the Principles. How did that one go? "Science appertains only to matter itself; not to the mysteries of matter or the desires of matter. The mysteries of matter belong to the gods, and the desires of matter belong to the king."

Or something like that.

He hadn't been quick with his lessons, like Bump-arch. His friend had scoffed at the Principles when alone with him, but had learned them by heart after a couple of offhand readings. Snubnose would sweat and sweat and think he had them, but when the time came to recite, the words would fly out the window into the fresh-smelling air.

Old Crookback had got so disgusted with him once that he had put him on bread and water. And then Bump-arch had sneaked out over the city wall and had caught a rabbit in a homemade trap and had talked one of the women of the settled Bowmen into cooking it for them. Gods, that had tasted good at midnight....

The circle of scientists was getting noisy. Snubnose's nearest neighbors were loudly rehashing the latest Private Law marriage. Snubnose wondered suddenly, why didn't the demonstration start? The Grandmaster had said, "Time." Was there trouble?

In the center of the Field, while Bump-arch stood apart, the dignitaries were carrying on one of those exasperating public wrangles, obvious but inaudible. The godsman was doing most of the talking, waving a plump arm. The Grandmaster looked unhappy, the kingsman looked important, and Crookback looked polite.

The godsman was so excited he absent-mindedly scratched his bare buttock. He caught himself and blushed—a total affair for a godsman—and during his embarrassment, Crookback began to talk. The godsman kept shaking his head and interrupting, but Crookback went on talking, and finally the godsman seemed to give a reluctant consent.

The Grandmaster raised his hand high, with the fingers spread, and a girl apprentice burst from the door of the Ready Hall. She ran across the Field, and two scientists smilingly moved aside to let her through. She stood panting before the Grandmaster. He handed her the symbolic messenger's key and spoke to her briefly—briefly for the Grandmaster.

She was off on the run.

Snubnose didn't know what was happening, but it looked as if the godsman had made some kind of a concession. He was sure that must be for the good and felt relieved—until the Grandmaster, leaning on his copper staff, addressed the guildfolk.

The Grandmaster began: "The holy one submitted an objection concerning a possible violation of the Principles and proposed to forbid the demonstration by the Candidate."

If that stood, Bump-arch would probably be tried for sacrilege in Godsmen's Castle. Yet the godsman had seemed to give ground....

"Needless to say, both the distinguished master of the Candidate and I myself, speaking individually for ourselves, and, in my own case especially, speaking for the Guild of Scientists as a body, assured the holy one of our reverent adherence to the Principles, and—"

He was interrupted by the angry voice of the godsman.

"Get on!"

The guildfolk buzzed. As often as they might have liked to tell their Grandmaster to get on, this was an insult to the Guild. But they were quickly silent, for it was an insult they would have to swallow, at least in public.

The Grandmaster swallowed it too, visibly gulping, and he said mildly, "The holy one has generously agreed to submit the issue to the High arbiter of the Guild of Lawyers, and the High Arbiter has been sent for."

It was the last thing said that alarmed Snubnose, and he looked at his sister and saw that for the first time her face was tight with unease. The High Arbiter was an old friend of their mother's, which was not likely to make him a friend of theirs today. He moved in the same snobbish society as their mother and had many times clucked with her about Proudwalk's "infatuation for that lowborn young man."

Snubnose would have liked to leave his place in the circle of scientists and join Proudwalk, but it was against Acknowledged Custom to change position once the circle was formed.

Everyone now was shuffling uncomfortably in the hot sun, except the godsman who was exposed to the cooling air and had the godsmen's secret of escaping sunburn. And Bump-arch, who looked as uncomfortable as anybody else but did not shuffle. He stood still and straight while sweat ran down his face into the tight black neckband of an apprentice. Once he seemed to look at Snubnose and wink, or perhaps he was only winking the sweat away.

An elephant moved slowly down the Street of Ward and onto the Field of Proof. It was a ponderous metal ovoid bearing on its roof a velvet pavilion with the curtains drawn. The circle of scientists parted and opened, and the elephant, with much grinding, came to a stop a few feet from the group in the center of the Field.

The driver, an apprentice lawyer, climbed from his hole and parted the curtains of the pavilion. The High Arbiter looked out at the world with a sour expression. He did not descend.

"I will hear the holy one first," he said from his roost.

The godsman raised his hands to the sun, and spoke.

"Wise one! The Candidate and his master, abetted by the Grandmaster of the Guild of Scientists, are shamelessly defying the Principles. The Candidate is preparing to demonstrate the accelerated movement of matter into the future. That is a mystery of matter. Only the gods can know the path that things take from the dimming past to the dark future. Scientists must confine themselves to their arts and not try to steal the mysteries belonging to the gods.

"The gods grant knowledge of mysteries to godsmen who have humbly supplicated, not to thieves. Let the scientists work to improve the fire-wheels that spin through the night seeking out the encampments of the Bowmen. Let them mix better fertilizers to sell to the Lords of the West. Let them keep in repair the ancient elephants for the honor of our exalted citizens."

The High Arbiter looked slightly less sour, and he nodded shortly. "I will hear the Grandmaster of the Guild of Scientists," he said.

The Grandmaster lifted his head.

"Wise one!" he said. "The godsman jibes, and with some basis. Generation to generation, the fire-wheels spin more slowly and seek less surely. The fertilizers grow leaner. The ceremonial elephants are fewer and worse. Perhaps the godsmen are not supplicating hard enough for solutions to mysteries of matter—solutions which would enable the scientists to control matter. In the impious days before the Principles, matter served mystery and mystery served matter, and by some inexplicable mercy of the gods, things went very well."

Years of banality, years of caution, years of looking to his retirement offering had, for a little while, lost their hold on him.

Snubnose was silently raging. What a place, he thought, for the Grandmaster to burst out with that kind of thing. True, scientists sometimes talked that way in the Guild social rooms, especially after drinking illegal grain distillate, but here it could only hurt Bump-arch's cause.

Snubnose looked at his friend. Bump-arch was trying to suppress a jubilant smile. Surprised, Snubnose looked at his sister. She was jumping up and down with pleasure, as he hadn't seen her do for at least two years.

"Romantics," he said to himself.

The High Arbiter had a talent for looking displeased, and now he did not stint.

"I note the Grandmaster's improper tone," he said stiffly. "Furthermore, his remarks are irrelevant to the issue. The holy one says that the demonstration treats of a mystery of matter in violation of the Principles. In view of the Grandmaster's failure to refute that, it is highly probable. However, it will have to be established by authority and precedent—unless the demonstration involves an idea specifically forbidden, which would be conclusive. I will hear the holy one."

"There is indeed a forbidden idea. It is known from tradition and old texts that the mathematic of accelerated movement through time involves imaginary numbers. At the conference of 1480 DRC it was confirmed that imaginary numbers are a metaphysical concept forbidden to scientists."

"I will hear the Candidate's master."

A light cloud was filtering the sunlight, and the old man seemed cool and calm. He took a step to a little mound of good grass as if he were climbing to a rostrum.

"Wise one! Neither the holy one nor our own Grandmaster—both devoted patriots with their minds on the welfare of the City—thought to bring one very important fact to your attention. My apprentice's demonstration is not an original experiment; it is a reconstructed experiment. By Acknowledged Custom, reconstructed experiments are permitted regardless of mysteries and ideas so long as the experimenter does not comprehend any impious theory but merely follows the practical directions of old texts.

"I declare that my apprentice is ignorant of the theory of his demonstration—and who is in a better position to know than his master?"

Snubnose rejoiced. He was ready to forgive even the bread and water. In a few sentences Crookback had excused the Grandmaster's rashness, had made good the Grandmaster's oversight, and had set forth a strong case for Bump-arch.

"I will hear the holy one."

"Let him prove that!" the godsman shouted.

"I will hear the Candidate's master."

"I regret that I cannot prove it absolutely. Negatives are difficult of proof. I suggest that the Candidate swear to his ignorance by the God Mother-Father."

"You should know that apprentices are not eligible to take oaths," the High Arbiter said impatiently, dropping the formal manner as if in a hurry to finish the proceedings—and finish Bump-arch.

Encouraged, the godsman cried, "Let Crookback swear to it. He was willing to declare it."

"Will you?" the High Arbiter asked Crookback.

"Though I am sure of the truth, my reverence for the God Mother-Father is too great to permit me to swear to the contents of another's mind—"

"That, and not wanting to be tried for false swearing," Snubnose muttered. He admired his old master a lot less.

"—but I will swear by the God Mother-Father that I myself am ignorant of the theory."

"What good is that?" the godsman demanded.

Cleverly, the master stood in respectful silence. There was an awkward pause—awkward for the godsman and the High Arbiter—and then the High Arbiter collected himself and said, "The question may be answered. I will hear the Candidate's master."

"I am shocked and saddened," said Crookback, "that the holy one believes that apprentices, still wearing their neckbands, excel in wisdom the masters of the guilds."

The High Arbiter's driver, who had been squatting meekly by the elephant, suddenly let loose a screaming laugh, which he cut off just as suddenly with a scared catch of breath.

"I will hear the oath," the High Arbiter said.

Crookback swore by the God Mother-Father while the godsman glowered. The High Arbiter said, "The demonstration may proceed. My apprentices will present my bills tomorrow, including commutation of fees for twenty journeyman lawyers, since you did not place the issue in King's Courts."

Everybody winced, and the elephant rumbled away.

The doors of the Ready Hall opened, and the whole body of apprentice scientists marched on the Field. They carried sections of steel sheet, lengths of magnesium tubing, and parts of machines unfamiliar to the guildfolk. Under Bump-arch's direction they began to assemble the equipment and to enclose it in a small building.

Bump-arch had planned well. They put the components together quickly, and marched from the Field. They had erected a cubical chamber of bright steel with an opening near the ground just big enough for a person—not too fat a person—to crawl through. Above the opening a closing panel was suspended in grooves.

The Grandmaster and the godsman and the kingsman inspected the setup with the peculiar ignorant attention of high officials. Each walked around the cube once and rapped it with his fingers here and there. Each solemnly stooped to the ground and put his head in the opening, although it was dark inside and nothing was visible. The plump godsman made a move as if to crawl in, then backed away.

The kingsman brushed dust from his cloak, and the inspection seemed to be over. The three officials and Crookback withdrew to the circle of scientists and stood just within it, a little to the left of Snubnose.

Bump-arch took hold of the door panel, the only projection on the smoothness of the cube, and scrambled to the roof, where he could be seen by the whole circle.

Now Bump-arch was really enjoying himself, Snubnose thought. And Proudwalk was enjoying Bump-arch with her big eyes.

"Elder ones, whether my experiment succeeds or fails, the outcome will be self-evident. I make no qualifications and prepare no excuses. I will now go ahead with the demonstration."

Snubnose said to himself, "It's a better performance than the High Arbiter gave on his elephant." He would have liked to yell some words of encouragement.

"Before I start," Bump-arch added, "as required by the Laws of the Guild, I ask, are there any among you who wish to inspect my apparatus?"

It was no longer considered good manners to accept that invitation, but a journeyman physicist named Red-hair stepped forward. He walked very carefully, and Snubnose wondered how much grain distillate he had drunk that morning.

Before he reached the steel chamber, Red-hair yelled to the Candidate, "Tell me how to start it. I don't like our times anyway."

"It's not going very far," Bump-arch said easily.

"It's not going anywhere, boy," Red-hair roared. "Everybody knows that. I don't know why we've wasted so much time today."

"You'd better not move any dials! There are a couple of ten-day lamps inside, if you want to look around."

Red-hair crawled through the opening. Five minutes later he crawled out, his hair in his eyes. "I can't make anything of it," he said to everybody in general, and he resumed his place in the circle.

"Now, elder ones, does anyone else wish to inspect the apparatus?"

"I do!"

It was Proudwalk.

She walked on grass and over the patches of shifting dust; walked with the graceful, slightly affected manner that had given her the name. There was the pride in her walk, and there was sexuality.

Bump-arch leaped to the ground to meet her. He bowed as if they were at the King's Councillor's Ball and he were asking her for the dance. Proudwalk touched her palms together in the stylized gesture of acceptance. Immediately she slipped through the entrance. Bump-arch stooped, and quickly followed her. The door panel dropped down its grooves, sealing the chamber.

The scientists chattered; the godsman shouted.

The kingsman raised his voice. "What's going on, Grandmaster?"

"A reconstructed demonstration attempting the accelerated movement of matter through time to the relatively near future by an apprentice who, having completed the requisite service, has been admitted to candidature for the rank of journeyman physicist."

The Grandmaster took a breath.

"Ask the Candidate's master," the godsman said, with the calmness now of more intense anger. "You heard him trick the High Arbiter into ruling that a mystery of matter is not a mystery and a forbidden idea is not forbidden. Maybe he can convince you that a desire of matter is not a desire of matter."

Crookback spoke up at once. "It would seem an unlikely place to give way to desire, but I am an old bachelor, as ignorant of the desires of matter as of its mysteries. However, young men and women frequently work together on scientific experiments."

"Not in windowless boxes," said the kingsman. "And who gave her leave to help the Candidate? There is something odd about this whole demonstration, and I'm going to find out what it is."

The kingsman strode to the little building. The sun had returned in full brightness, and the alloyed-steel walls were glistening. The kingsman glistened too: the smooth fabric of his cloak—his silver ornaments—his mace of massy silver.

Sharply he rapped with his mace on the closed door. There was afterwards silence. He rapped again. There was again silence.

The kingsman lost his temper. He brought back his mace and swung it fiercely toward the wall of the chamber.

The blow of massy silver against steel did not come. The wildly swinging arm and mace whirled through the air. The kingsman fell forward.

He sprawled, splendid and ridiculous: defeated by air.

There was no cubical building. The guildfolk faced each other across the Field. Where the steel cube had stood, the kingsman was getting to his knees.

Floating gently through the air, separating and drifting down, were many sheets of paper.

Snubnose picked up one of the papers as it fell. It was headed "COPY OF CONTRACT" and dated that Day of the Candidate, 155th-1712 DRC. It said: "Hereby do Bump-arch, apprentice physicist, and Proudwalk, journeywoman biologist, contract under Private Law a marriage between them: and do undertake to dwell as husband and wife under the same roof for a period of five years in validation of this marriage: such period to terminate for purposes of the Private Law upon 155th-1717 DRC, but to continue under other roofs for the duration of their lives."

"Time," said the Grandmaster.

Walking slowly home to face his mother, Snubnose said to himself, "This one will keep the Guild of Lawyers busy for the duration of all our lives."