MAM'SELLE JO

MAM'SELLE JO

BY

HARRIET T. COMSTOCK

Illustrated

By

E. F. Ward

TORONTO

THE MUSSON BOOK CO.

LIMITED

1918

PRINTED IN GARDEN CITY, N. Y., U. S. A.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

DEDICATION

Beside each cradle—so an old legend runs—Fate stands

and with just scale weighs the sunshine and shadow to

which every life is entitled. But if Dame Fate is in a

kindly mood 'tis said she throws in a bit of extra

brightness for the pure joy of giving.

BARBARA WILSON COMSTOCK

you are

"THE EXTRA BIT"

To you I dedicate this book

HARRIET T. COMSTOCK.

Flatbush—Brooklyn, N. Y.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

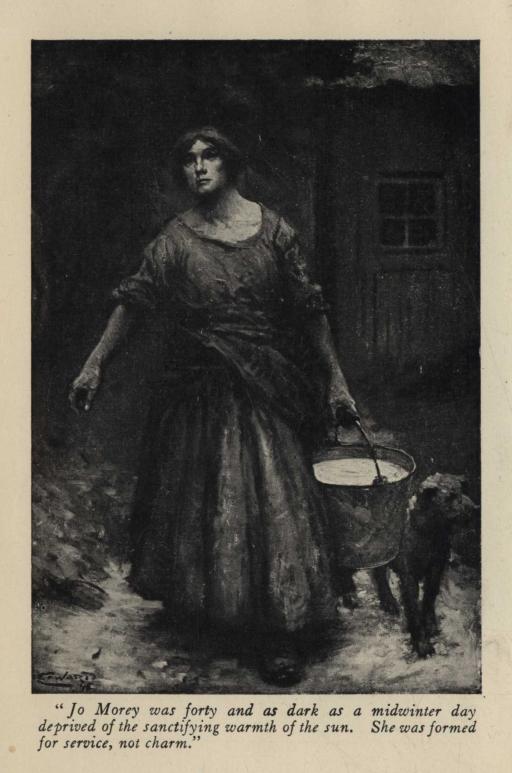

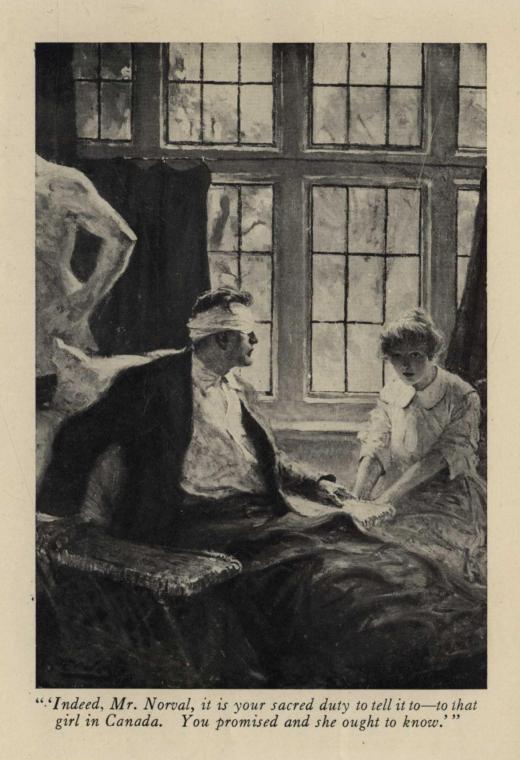

"Jo Morey was forty and as dark as a midwinter day deprived of the sanctifying warmth of the sun. She was formed for service, not charm" . . . Frontispiece

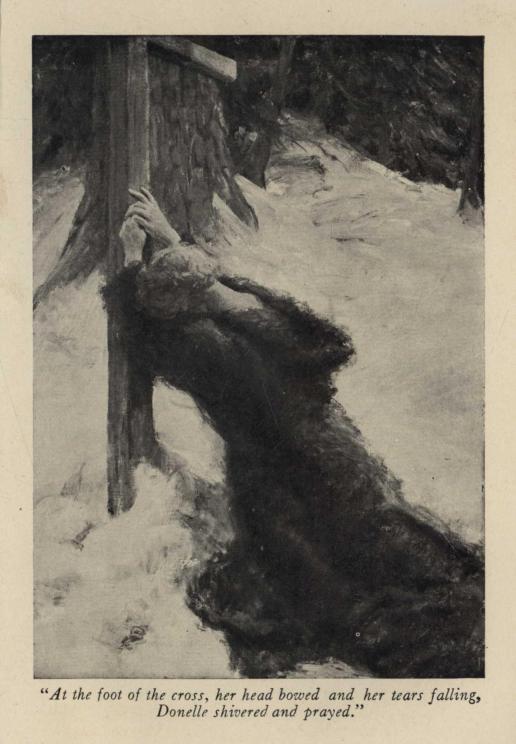

"At the foot of the cross, her head bowed and her tears falling, Donelle shivered and prayed"

LIST OF CHARACTERS

This is a story of a woman who having no beauty of face or form was deprived for a time of the beautiful things of life.

Then she prayed to the God of men and He gave her material success. Having this she raised her eyes from the earth which had been her battlefield and made a vow that she would take what was possible from the odds and ends of happiness and weave what she could into love and service.

Through this she won a reward far beyond her wildest dreams and found peace and joy.

"You are a strange man"—she said to him who discovered her.

"You are a very strange woman, Mam'selle"—he returned.

Besides these two there are:

Captain Longville—and his wife Marcel.

Pierre Gavot—and his wife Margot who found life paid because of her boy Tom.

Old Father Mantelle—more friend than priest who helped them all.

But Dan Kelly—of Dan's Place—better known as The Atmosphere—made life difficult for them all.

Then after a time the Lindsays of the Walled House drew things together and opened a new vista. Here we find:

Man-Andy; called by some, The Final Test, or Old Testy.

James Norval—who had some talent and an occasional flash of genius.

Katherine Norval, his wife, who from the highest motives nearly drove him to hell.

There are Sister Angela with the convenient memory and Little Sister Mary with the Lost Look.

Mary Maiden who happened into the story for a second only.

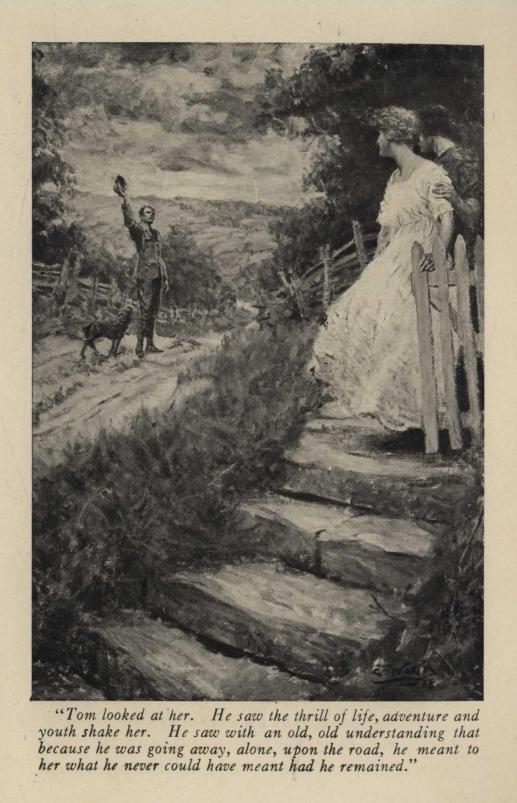

And lastly: Tom Gavot who dreamed of roads, played with roads, made roads, and at last found The Right Road which led him to the top, from that high point he saw—who can tell what?

And—Donelle who early prayed that she might be part of life and vowed that she was willing to suffer and pay. Life took her at her word, and used her.

MAM'SELLE JO

CHAPTER I

MAM'SELLE JO IS SET FREE

One late afternoon in September Jo Morey—she was better known in the village of Point of Pines as Mam'selle Jo—stood on the tiny lawn lying between her trim white house and the broad highway, lifted her eyes from the earth, that had long been her battlefield, and murmured aloud as lonely people often do,

"Mine! Mine! Mine!"

She did not say this arrogantly, but, rather, reverently. It was like a prayer of appreciation to the only God she recognized; a just God who had crowned her efforts with success. Not to a loving God could Mam'selle pray, for love had been denied her; not to a beautiful God, for Jo had yet to find beauty in her hard and narrow life; but to the Power that had vindicated Itself she was ready to do homage.

"Mine! Mine! Mine!"

Jo was forty and as dark as a midwinter day deprived of the sanctifying warmth of the sun. She was short and muscular, formed for service, not charm. Her mouth was the mouth of a woman who had never known rightful self-expression; her nose showed character, but was too strong for beauty; heavy brows shaded her eyes, shielding them from the idly-curious, but when those eyes were lifted one saw that they had been in God's keeping and preserved for happier outlooks. They were wonderful eyes. Soft brown with the sheen of horsechestnut.

Mam'selle's attire was as unique as she was herself. It consisted, for the most part, of garments which had once belonged to her father who had departed this life fifteen years before, rich in debts and a bad reputation; bequeathing to his older daughter his cast-off wardrobe and the care of an imbecile sister.

Jo now plunged her hands in the pockets of the rough coat; she planted her feet more firmly in the heavy boots much too large for her and, in tossing her head backward, displaced the old, battered felt hat that covered the lustrous braids of her thick, shining hair.

Standing so, bare headed, wide eyed, and shabby, Jo was a dramatic figure of victory. She looked at the neatly painted house, the hill rising behind it crowned with a splendid forest rich in autumn tints. Then her gaze drifted across the road to the fine pastures which had yielded a rare harvest; to the outhouses and barns that sheltered the wealth chat had been lately garnered. The neighing of Molly, the strong little horse; the rustling of cows, chickens, and the grunting of pigs were like sounds of music to her attentive ears. Then back to the house roved the keen but tender eyes, and rested upon the massive wood pile that flanked the north side of the house beginning at the kitchen door and ending, only, within a few feet of the highway.

This trusty guardian standing between Jo and the long, cold winter that lurked not far off, filled her with supreme content. Full well she knew that starting with the first log, lying close to her door, she might safely count upon comfort and warmth until late spring without demolishing the fine outline of the sturdy wall at the road-end!

That day Jo had paid the last dollar she owed to any man. She had two thousand dollars still to her credit; she was a free woman at last! Free after fifteen years of such toil and privation as few women had ever known.

She was free—and——

Just then Mam'selle knew the twinge of sadness that is the penalty of achievement. Heretofore there had been purpose, necessity, and obligation but now? Why, there was nothing; really nothing. She need not labour early and late; there was no demand upon her. For a moment her breath came quick and hard; her eyes dimmed and vaguely she realized that the struggle had held a glory that victory lacked.

Fifteen years ago she had stood as she was standing now, but had looked upon a far different scene. Then the house was falling to decay, and was but a sad shelter for the poor sister who lay muttering unintelligible words all day long while she played with bits of bright coloured rags. The barns and outhouses were empty and forlorn, the harvest a failure; the wood pile dangerously small.

Jo had but just returned from her father's funeral and she was wondering, helplessly, what she could do next in order to keep the wretched home, and procure food and clothing for Cecile and herself. She was thankful, even then, that her father was dead; glad that her poor mother, who had given up the struggle years before, did not complicate the barren present—it would be easier to attack the problem single handed.

And as she stood bewildered, but undaunted, Captain Longville came up the highway and paused near the ramshackle gate. Longville was the power in Point of Pines with whom all reckoned, first or last. He was of French descent, clever, lazy, and cruel but with an outward courtesy that defied the usual methods of retaliation. He had money and capacity for gaining more and more. He managed to obtain information and secrets that added to his control of people. He was a silent, forceful creature who never expended more than was necessary in money, time, or words to reach his goal—but he always had a definite goal in view.

"Good day, Mam'selle," he called to Jo in his perfect English which had merely a trace of accent, "it was a fine funeral and I never saw the father look better nor more as he should. He and you did yourselves proud." Longville's manner and choice of words were as composite as were his neighbours; Point of Pines was conglomerate, the homing place of many from many lands for generations past.

"I did my best for him," Jo responded, "and it's all paid for, Captain."

The dark eyes were turned upon the visitor proudly but helplessly.

"Paid, eh?" questioned Longville. This aspect of affairs surprised and disturbed him. "Paid, eh?"

"Yes, I saved. I knew what was coming."

"Well, now, Mam'selle, I have an offer to make. While your father lived I lent, and lent often, laying a debt on my own land in order to save his, but pay day has come. This is all—mine! But I'm no hard and fast master, specially to women, and in turning things about in my mind I have come to this conclusion. Back of my house is a small cabin, I offer it to you and Cecile. Bring what you choose from here and make the place homelike and, for the help you give Madame when the States' folks summer with us, we'll give you your clothing and keep. What do you say, eh?"

For full a minute Jo said nothing. She was a woman whose roots struck deep in every direction, and she recoiled at the idea of change. Then something happened to her. Without thought or conscious volition she began to speak.

"I—I want the chance, Captain Longville, only the chance."

"The chance, eh? What chance, Mam'selle?"

"The chance to—to get it back!" The screened eyes seemed to gather all the old, familiar wretchedness into their own misery.

Longville laughed, not brutally, but this was too much, coming as it did from Morey's daughter.

"Why, Mam'selle," he said, "the interest hasn't been paid in years."

"The interest—and how much is that?" murmured Jo.

"Oh, a matter of a couple of hundreds." This was flung out off-handedly.

"But if—if I could pay that and promise to keep it up, would you give me the chance? My money is as good as another's and the first time I fail, Captain, I'll fetch Cecile over to the cabin and sell myself to you."

This was not a gracious way to put it and it made Longville scowl, still it amused him mightily. There was a bit of the sport in him, too, and the words, wild and improbable as they were, set in motion various ideas.

If Jo could save from the wreck of things in the past enough money to pay for the funeral might she not, the sly minx, have saved more? Stolen was what Longville really thought. Ready money, as much as he could lay hands on, was the dearest thing in life to him and the fun of having any one scrimping and delving to procure it for him was a joy not to be lightly thrown away. And might he not accomplish all he had in mind by giving Jo her chance? He did not want the land and the ramshackle house, except for what they would bring in cash; and if Mam'selle must slave to earn, might she not be willing to slave in his kitchen as well as in another's? To be sure he would have, under this new dispensation, to pay her, or credit her, with a certain amount—but he could make it desirably small and should she rebel he would threaten her, in a kindly way, with disinclination to carry on further business relations with her.

So Longville pursed up his thin lips and considered.

"But the money, the interest money, Mam'selle, the chance depends upon that."

Jo turned and walked to the house. Presently she came back with a cracked teapot in her hands.

"In this," she said slowly as if repeating words suggested to her, "there are two hundred and forty-two dollars and seventy-nine cents, Captain. All through the years I have saved and saved. I've sold my linens and woollens to the city folks—I've lied—but now it will buy the chance."

A slow anger grew in Longville's eyes.

"And you did this, while owing everything to me?" he asked.

"It was father who owed you; your money went for drink, for anything and everything but safety for Cecile and me. The work of my own hands—is mine!"

"Not so say our good laws!" sneered Longville, "and now I could take it all from you and turn you out on the world."

"And will—you?" Jo asked.

She was a miserable figure standing there with her outstretched hands holding the cracked teapot.

Longville considered further. He longed to stand well in the community when it did not cost him too much. Without going into details he could so arrange this business with Jo Morey that he might shine forth radiantly—and he did not always radiate by any means.

"No!" he said presently; "I'm going to give you your chance, Mam'selle, that is, if you give me all your money."

"You said—two hundred!"

"About, Mam'selle, about. That was my word."

"But winter is near and there is Cecile. Captain, will you leave me a bit to begin on?"

"Well, now, let us see. How about our building up your wood pile; starting you in with potatoes, pork, and the like and leaving say twenty-five dollars in the teapot? How about that, eh?"

"Will you write it down and sign?" Jo was quivering.

"You're sharp, devilishly sharp, Mam'selle. How about being good friends instead of hard drivers of bargains?"

"You must write it out and sign, Captain. We'll be better friends for that."

Again Longville considered.

The arrangement would be brief at best, he concluded.

"I'll sign!" he finally agreed, "but, Mam'selle, it's like a play between you and me."

"It's no play, Captain, as you will see."

And so it had begun, that grim struggle which lasted fifteen long years with never a failure to meet the interest; and, in due time, the payments on the original loan were undertaken. Early and late Jo slaved, denying herself all but the barest necessities, but she managed to give poor Cecile better fare.

During the second year of Jo's struggle, two staggering things had occurred that threatened, for a time, to defeat her. She had known but little brightness in her dun-coloured girlhood, but that little had been connected with Henry Langley the best, by far, of the young men of the place. He was an American who had come from the States to Canada, as many others had, believing his chance on the land to be better than at home. He was an educated man with ambitions for a future of independence and a free life. He bought a small farm for himself and built a rude but comfortable cabin upon it. When he was not working out of doors he was studying within and his only extravagances were books and a violin.

Jo Morey had always attracted him; her mind, her courage, her defiance of conditions, called forth all that was fine in him. Without fully understanding he recognized in her the qualities that, added to his own, would secure the success he craved. So he taught her, read with her, and made her think. He was not calculating and selfish, the crude foundation was but the safety upon which he built a romance that was as simple and pure as any he had ever known. The plain, brave girl with her quiet humour and delicate ideals appealed mightily to him. His emotions were in abeyance to his good common sense, so he and Jo had planned for a future—never very definite, but always sincere.

After the death of Morey, Jo, according to her bargain with Longville, went to help in the care of the summer boarders who, that year, filled Madame Longville's house to overflowing and brought in a harvest that the Captain, not his womankind, gathered. That was the summer when poor Jo, over-worked, worried at leaving Cecile alone for so many weary hours, grew grim and unlovely and found little time or inclination to play the happy part with Langley that had been the joy and salvation of their lives. And just then a girl from the States appeared—a delicate, pretty thing ordered to the river-pines to regain her health. She belonged to the class of women who know no terminals in their lives, but accept everything as an open passage to the broad sea of their desires. She was obliged to work for her existence and the effort had all but cost her her life; she must get someone, therefore, to undertake the business for the future. Her resources were apparently limited, while the immediate necessity was pressing. Since nothing was to her finite and binding, she looked upon Henry Langley and beheld in him a possibility; a stepping stone. She promptly began her attack, by way of poor Jo, who, she keenly realized, was her safest and surest course to Langley's citadel. She made almost frantic efforts to include the tired drudge in the summer frivolities; her sweet compassion and delicate prettiness were in terrific contrast to Jo's shabbiness and lack of charm. While Langley tried to be just and loyal he could but acknowledge that Jo's blunt refusals to accept, what of course she could not accept, were often brutal and coarse. Then, as his senses began to blind him, he became stupidly critical, groping and bungling. He could not see, beneath Jo's fierce retorts to his very reasonable demands, the scorching hurt and ever-growing recognition of defeat.

It was the old game played between a professional and an amateur—and the professional won!

Quite unbeknown to poor Jo, toiling in Madame Longville's kitchen, Langley quietly sold his belongings to the Captain and, taking his prize off secretly, left explanations to others.

Longville made them.

"Mam'selle," he said, standing before Jo as she bent over a steaming pan of dishes in the stifling kitchen, "we've been cheated out of a merry wedding."

"A wedding?" asked Jo listlessly, "has any one time to marry now?"

"They made time and made off with themselves as well. Langley was married last night and is on his way, heaven knows where!"

Jo raised herself and faced Longville. Her hair was hanging limply, her eyes were terror-filled.

"Langley married and gone?" she gasped. Then: "My God!"

That was all, but Longville watching her drew his own evil conclusions and laughed good-naturedly.

"It's all in the day's work, Mam'selle," he said, and wondered silently if the slave before him would be able to finish out the summer.

Jo finished out the summer efficiently and silently. In September Cecile simply stopped babbling and playing with rags and became wholly dead. After the burial Jo, with her dog at her heels, went away. No one but Longville noticed. Her work at his house was over; the last boarder had departed.

Often Jo's home was unvisited for weeks at a time, so her absence, now, caused no surprise. Two weeks elapsed, then she reappeared, draggled and worn, the dog closely following.

That was all, and the endless work of weaving and spinning was resumed. Jo invented three marvellously beautiful designs that winter.

But now, this glorious autumn day, she stood victoriously reviewing the past. Suddenly she turned. As if playing an appointed part in the grim drama, Longville again stood by the gate looking a bit keener and grayer, but little older. In his hands, signed and properly executed, were all the papers that set Jo free from him forever unless he could, by some other method, draw her within his power. That money of hers in the bank lay heavy on his sense of propriety.

"Unless she's paying and paying me," he pondered, "what need has she of money? Too much money is bad for a woman—I'll give her interest."

And just then Jo hailed him in the tone and manner of a free creature.

"Ah, Captain, it's a good day, to be sure. A good day!"

"Here are the papers!" Longville came near and held them toward her.

"Thanks, there was no hurry."

"And now," Longville leered broadly. "'Tis I as comes a-begging. How about those hundreds in the bank, Mam'selle? I will pay the same interest as others and one good turn deserves another."

But Jo shook her head.

"No. I'm done with borrowing and lending, Captain. In the future, when I part with my money, I will give it. I've never had that pleasure in my life before."

"That's a course that will end in your begging again at my door." Longville's smile had vanished.

"If so be," and Jo tossed her head, "I'll come humbly, having learned my lesson from the best of teachers."

Jo plunged her hands deeper in the pockets of her father's old coat.

"A woman and her money are soon parted," growled Longville.

"You quote wrong, Captain. It is a fool and money; a woman is not always a fool."

Longville reserved his opinion as to this but assumed his grinning, playful manner which reminded one of the antics of a wild cat.

"Ah, Mam'selle, you must buy a husband. He will manage you and your good money."

A deep flush rose to Jo's dark face; her scowling brows hid her suffering eyes.

"You think I must buy what I could not win, Captain?" she asked quietly. "God help me from falling to such folly."

The two talked a little longer, but the real meaning and purpose that had held them together during the past years was gone. They both realized this fully, for the first time, as they tried now to make talk.

They spoke of the future only to find that they had no common future. Jo retreated as Longville advanced.

They clutched at the fast receding past with the realization that it was a dead thing and eluded them already.

The present was all that was left and that was heavy with new emotions. Longville presently became aware of a desire to hurt Jo Morey, since he could no longer control her; and Jo eyed the Captain as a suddenly released animal eyes its late torturer: free, but haunted by memories that still fetter its movements. She wanted to get rid of the disturbing presence.

"Yes, Mam'selle, since you put it that way," Longville shifted from one foot to the other as he harked back to the words that he saw hurt, "you must buy a husband."

"I must go inside," Jo returned bluntly, "good afternoon, Captain." And she abruptly left him.

It was rather awkward to be left standing alone on Jo Morey's trim lawn, so Longville muttered an uncomplimentary opinion of his late victim and strode toward home.

CHAPTER II

MAM'SELLE MUST BUY A HUSBAND

Longville turned the affairs of Jo Morey over and over in his scheming mind as he walked home. He had made the suggestion as to buying a husband from a mistaken idea of pleasantry, but its effect upon Jo had caused him to take the idea seriously, first as a lash, then as purpose. By the time he reached home he had arrived at a definite conclusion, had selected Jo's future mate, and had all but settled the details.

He ate his evening meal silently, sullenly, and watched his wife contemplatively.

There were times when Longville had an uncomfortable sensation when looking at Marcel. It was similar to the sensation one has when he discovers that he has been addressing a stranger instead of the intimate he had supposed.

He was the type of man who among his own sex sneers at women because of attributes with which he endows them, but who, when alone with women, has a creeping doubt as to his boasted conclusions and seeks to right matters by bullying methods.

Marcel had been bought and absorbed by Longville when she was too young and ignorant to resist openly. What life had taught her she held in reserve. There had never been what seemed an imperative need for rebellion so Marcel had been outwardly complacent. She had fulfilled the duties, that others had declared hers, because she was not clear in her own mind as to any other course, but under her slow outward manner there were currents running from heart to brain that Longville had never discovered, though there were times, like the present, when he stepped cautiously as he advanced toward his wife with a desire for coöperation.

"Marcel," he said presently with his awkward, playful manner, "I have an idea!"

He stretched his long legs toward the stove. He had eaten to his fill and now lighted his pipe, watching his wife as she bent over the steaming pan of dishes in the sink.

Marcel did not turn; ideas were uninteresting, and Longville's generally involved her in more work and no profit.

"'Tis about Pierre, your good-for-nothing brother."

"What about him?" asked Marcel. Blood was blood after all and she resented Longville's superior tone.

"Since Margot died he has had a rough time of it," mused the Captain, "caring for the boy and shifting for himself. It has been hard for Pierre."

"You want him and Tom—here?" Marcel turned now, the greasy water dripping from her red hands. She had small use for her brother, but her heart yearned over the motherless Tom.

"God forbid," ejaculated Longville, "but a man must pity such a life as Pierre's."

"Pierre takes his pleasures," sighed Marcel, "as all can testify."

"You mean that a man should have no pleasure?" snapped the Captain. "You women are devilish hard."

"I meant no wrong. 'Tis no business of mine."

"'Tis the business of all women to marry off the odds and ends"; and now Longville was ready. He launched out with a clear statement of Jo Morey's finances and the absolute necessity of male control of the same. Marcel listened and waited.

"Mam'selle Jo Morey must marry," Longville continued. He had his pipe lighted and between long puffs blinked luxuriously as he outlined the future. "She has too much money for a woman and—there is Pierre!"

"Mam'selle Jo and Pierre!" Almost Marcel laughed. "But Mam'selle is so homely and Pierre, being the handsome man he is, detests an ugly woman."

"What matters? Once married, the good law of the land gives the wife's money to her master. 'Tis a righteous law. And Pierre has a way with women that breaks them or kills them—generally both!"

This was meant jocosely, but Marcel gave a shudder as she bent again over the steaming suds.

"But Mam'selle with money," she murmured more to herself than to Longville. "Will Mam'selle sell herself?"

This almost staggered Longville. He took his pipe from his lips and stared at the back of the drudge near him. Then he spoke slowly, wonderingly:

"Will a woman marry? What mean you? All women will sell their souls for a man. Mam'selle, being ugly, must buy one. Besides——" And here Longville paused to impress his next words.

"Besides, you remember Langley?"

For a moment Marcel did not; so much had come and gone since Langley's time. Then she recalled the flurry his going with one of the summer people had caused, and she nodded.

"You know Langley walked and talked with Mam'selle before that red and white woman from the States caught him up in her petticoat and carried him off?"

It began to come back to Marcel now. Again she nodded indifferently.

"And some months after," Longville was whispering as if he feared the cat purring under the stove would hear, "some months later, what happened then." Marcel rummaged in her litter of bleak memories.

"Oh! Cecile died!" She brought forth triumphantly.

"Cecile died, yes! And Mam'selle went away. And what for?" The whispered words struck Marcel's dull brain like sharp strokes.

"I do not know," she faltered.

"You cannot guess—and you a woman?"

"I cannot."

"Then patch this and this together. Why does a woman go away and hide when a man has deserted her? Why?"

Marcel wiped the suds from her red, wrinkled hands. She stared at her husband like an idiot, then she sat down heavily in a chair.

"And that's why Mam'selle will buy Pierre."

For a full moment Marcel looked at her husband as if she had never seen him before, then her dreary eyes wandered to the window.

Across the road, in the growing darkness, lay three small graves in a row. Marcel was seeking them, now, seeking them with all the fierce love and loyalty that lay deep in her heart. And out of those pitiful mounds little forms, oh! such tiny forms, seemed to rise and plead for Jo Morey.

Who was it that had shared the black hours when Marcel's babies came—and went? Whose understanding and sympathy had made life possible when all else failed?

"I'll do no harm to Mam'selle Jo Morey!" The tone and words electrified Longville.

"What?" he asked roughly.

"If what you hint is true," Marcel spoke as from a great distance, her voice trailing pitifully; "I'll never use it to hurt Mam'selle, or I could not meet my God."

"You'll do what I say!"

But as he spoke Longville had a sense of doubt. For the second time that day he was conscious of being baffled by a woman; his purposes being threatened.

"You may regret," he growled, "if you do not help along with this—this matter of Pierre. There will come a time when Pierre will lie at your door. What then, eh?"

"Is that any reason why I should throw him at the door of another woman?" Marcel's pale face twitched. "Why should a man expect any woman's door to open to him," she went on, "when he has disgraced himself all his life?"

Longville stirred restlessly. Actually he dared not strike his wife, but he had all the impulse to do so. He resorted to hoary argument.

"'Tis the unselfish, the noble woman who saves—man!" he muttered, half ashamed of his own words.

At this Marcel laughed openly. Something was rising to the surface, something that life had taught her.

"It's a poor argument to use when the unworthy one is the gainer by a woman's unselfishness," retorted Marcel. "Unless she, too, gets something out of her—her nobleness, I should think a man would hate to fling it always in her teeth."

Longville half rose; his jaw looked ugly.

"'Tis my purpose," he said slowly, harshly, "to marry Mam'selle and Pierre. I have my reasons, and if you cannot help you can keep out of the way!"

"Yes, I can do that," murmured Marcel. She had taken up her knitting and she rarely spoke while she knitted. She thought!

But if Longville's suggestion seemed to die in the mind of his own woman, it had no such fate in that of Jo Morey. When she went into her orderly house, after leaving the Captain, she put her papers on the table and stood staring ahead into space. She seemed waiting for the ugly thought he had left to follow its creator, but instead it clung to her like a stinging nettle.

"Buy a husband!" she repeated; "buy a husband."

Into poor Jo's dry and empty heart the words ate their way like a spark in the autumn's brush. The flame left a blackened trail over which she toiled drearily back, back to that one blessed taste she had had of love and happiness. Memories, long considered dead, rose from their shallow graves like spectres, claiming Mam'selle for their own at last.

She had believed herself beyond suffering. She had thought that loneliness and hard labour had secured her at least from the agony she was now enduring, but with the consciousness that she could feel as she was feeling, a sort of terror overcame her.

Her past days of toil had been blessed with nights of exhausted slumber. But with the newly-won freedom there would be hours when she must succumb to the tortures of memory. She could not go on slaving with no actual need to spur her, she must have a reason, a motive for existence. Like many another, poor Jo realized that while she had plenty to retire on, she had nothing to retire to, for in her single purpose of freeing herself from Longville, she had freed herself from all other ties.

But Jo Morey would not have been the woman she was if obstacles could down her. She turned abruptly and strode toward the barn across the road. Nick, her dog, materialized at this point. Nick had no faith in men and discreetly kept out of sight when one appeared. He was no coward, but caution was a marked characteristic in him and unless necessity called he did not care, nor deem it advisable, to display his feelings to strangers.

Jo felt for Nick an affection based upon tradition and fact. His mother had been her sole companion during the darkest period of her life and Nick was a worthy son of a faithful mother. Jo talked to the dog constantly when she was most troubled and confused. She devoutly believed she often received inspiration and solution from his strange, earnest eyes.

"Well, old chap," she said now as she felt his sturdy body press against her knee. "What do you think of that?"

Nick gave a sharp, resentful yelp.

"We want no man planting his tobacco in our front yard; do we, sir? He might even expect us to plant it!"

Jo always spoke editorially when conversing with Nick. "And fancy a man sitting by the new stove, Nick, spitting and snoring and kicking no doubt you, my good friend, if not me!"

Nick refused to contemplate such a monstrous absurdity. He showed his teeth in a sardonic grin and, to ease his feelings, made a dash after a giddy hen who had forgotten the way to the coop and was frantically proclaiming the fact in the gathering darkness.

"If that hussy," muttered Jo, "don't stick closer to the roost, I'll have her for dinner!" Then a light broke upon Jo's face. From trifles, often, our lives are turned into new channels. "I declare, I'll have her anyway! I'll live from now on like folks."

States' folks, Jo had in mind, the easy-going summer type. "Chicken twice a week, hereafter, and no getting up before daybreak."

Nick had chased the doomed hen to the coop and was virtuously returning when his mistress again addressed him.

"Nick, the little red cow is about to calve. What do you think of that?"

Nick thought very little of it. The red cow was a nuisance. She calved at off times of the year and had an abnormal affection for her offspring. She would not be comforted when it was torn from her for financial reasons. She made known her objections by kicking over milk pails and making nights hideous by her wailing; then, too, she had a way of looking at one that weakened the moral fibre. Nick followed his mistress to the cow shed and stood contemplatively by while Jo smoothed the glossy head of the offending cow and murmured:

"Poor little lass, you cannot understand, but you do not want to be alone, do you?" The animal pressed close and gave a low, sweet sound of appreciation.

"All right, girl. I'll fill Nick up and take a bite, then I'll be back and bide with you."

The mild maternal eyes now rested upon Nick and his grew forgiving!

"Come, Nick!" called Jo. "We'll have to hurry. The little red cow, once she decides, does not waste time. It's a snack and dash for us, old man, until after the trouble is over. But there's no need of early bed-going to-night, Nick, and before we sleep we'll have the fire in the stove!"

So Nick followed obediently, ate voraciously but rapidly, and Jo took her snack while moving about the kitchen and planning for the celebration that was to follow the little red cow's accouchement.

It must be a desolate life indeed, a life barren of imagination, that has not had some sort of star to which the chariot of desire has been hitched. Jo Morey had a vast imagination and it had kept her safe through all the years of grind and weariness. Her star was a stove!

Back in the time when her relations with Longville were growing less strained and she could look beyond her obligations and still see—money, she had closed the fireplace in the living room and bought, on the instalment plan, a most marvellous invention of iron, nickle, and glass, with broad ovens and cavernous belly, and set it up in state.

Jo's conception of honesty would not permit her to build a fire in the monster until every cent was paid, but she had polished it, almost worshipped before it, and had silently vowed that upon the day when she was free from all debt to man she would revel in such warmth and glory as she had never known before.

"No more roasted fronts and frozen backs,"

Mam'selle had secretly sworn. "No more huddling in the kitchen and scrimping of fires. From the first frost to the first thaw I'll have two fires going. The new stove will heat the north chamber and perhaps the upper room as well. 'Tis a wondrous heater, I'm told."

But the red cow's affairs had postponed the thrilling event. Still neither Jo nor Nick ever expected perfection in fulfillment and they took the delay with patient dignity.

Later they again started for the cow shed, this time guided by a lantern, for night had fallen upon Point of Pines.

Jo took a seat upon an upturned potato basket with Nick close beside her, and so they waited. Waited until all need and danger were past; then, tenderly stroking the head of the newly-made mother, Jo spoke in the tone that few ever heard. Margot Gavot had heard it as she drifted out of life, her hungry eyes fastened on Jo and the sobbing boy—Tom. Marcel Longville had heard it as she clung to the hard, rough hand that seemed to be her only anchor when life and death battled for her and ended in taking her babies. The little red cow had heard it once before and now turned her grateful eyes to Mam'selle.

"So! So, lass," murmured Jo; "we don't understand, but we had to see it through. Brave lass, cuddle the wee thing and take your rest. So, so!"

Then back to the house went Jo and Nick, the lantern swinging between them like a captured star.

A wonderful, uplifted feeling rose in Jo Morey's heart. She was unlike her old, unheeding self, she heeded everything; she started at the slightest sound and drew her breath in sharply. She was almost afraid of the sensation that overcame her. Depression had fled; exhilaration had taken its place. A sense of freedom, of adventure, possessed her. She was ready at last to fling aside the bonds and go forth! Then Nick stopped short and strained forward as if sensing something in the dark that not even the lantern could disclose.

"So, Nick!" laughed Jo, "you feel it, too? It's all right, old man. The mystery of the shed has upset us both. It's always the same, whether it comes to woman or creature. Something hidden makes us see it, but our eyes are blind, blind to the meaning."

Then Jo resorted to action. She carried a load of wood from the pile to the living room; with bated breath she placed it in the stove.

"Suppose it shouldn't draw?" she whispered to Nick, and struck a match. The first test proved this fear ungrounded. The draw was so terrific that it threatened to suck everything up.

In a panic Jo experimented with the dampers and soon had the matter in control. She was perspiring, and Nick was yelping and dashing about in circles, when the fire was brought to a sense of its responsibility, ceased roaring like a wild bull, and settled down into a steady, reliable body of glowing heat.

Then Jo drew a chair close, pulled up her absurd skirts, put her man-shod feet into the oven, and gave a sigh of supreme content.

Nick took the hint. Since this was not an accident but, apparently, a permanent innovation, it behooved him to adapt himself as his mistress had done. Behind the fiery monster there was a space, hot as Tophet, but commanding a good view. It might be utilized, so Nick appropriated it.

"There seems no end to what this stove can do," muttered Jo, twisting about and disdaining the smell of overheated leather and wool. "No more undressing in the kitchen and freezing in bed in the north chamber. I've never been warm in winter since I was born, but that's done with now! I shouldn't wonder if I might open the room upstairs after a bit—I shouldn't wonder!"

Then Jo caught a glimpse of her reflection in the mirror over the stove! As she looked, her excitement lessened, the depression of the afternoon overcame her. She acknowledged that she looked old and ugly. A woman first to be despised, then ridiculed, by men. "Buy a husband!" She, Jo Morey, who had once had her vision and the dreams of a woman. She, who had had so much to offer in her shabby youth, so much that was fine and noble. Intelligence that had striven with, and overcome, obstacles; a passion for service, passion and love. All, all she had had except the one, poor, pitiful thing called beauty. That might have interpreted all else to man for her and won her the sacred desires of her soul.

She had had faith until Langley betrayed it. She had scorned the doubt that, what she lacked, could deprive her of her rights.

Through a never-to-be-forgotten spring and early summer she had been as other girls. Love had stirred her senses and set its seal upon the man who shared her few free hours. He had felt the screened loveliness of the spirit and character of Jo Morey; had revelled in her appreciation and understanding. He had loved her; told her so, and planned, with her, for a future rich in all that made life worth while. That was the spring when Jo had first noticed how the sand pipers, circling against the blue sky, made a brown blur that changed its form as the birds rose higher or when they dipped again, disappearing behind the tamarack pines on the hilltop.

That was the spring when the swift, incoming tide of the St. Lawrence made music in the fragrant stillness and she and Langley had sung together in their queer halting French "A la Claire Fontaine" and had laughed their honest English laughs at their clumsy tongues struggling with the rippling words.

And then; the girl had come, and—the end!

Jo believed that something had died in her at that time, but it had only been stunned. It arose now, and in the still, hot room demanded its own!

"Fifteen years ago!" murmured Jo and looked about at the evidences of her toiling years: the quaint room and the furnishings. The floor was painted yellow and on it were islands of gay, tinted rugs all woven by her tireless hands. There were round rugs and square rugs, long ones and short ones. In the middle of the room was a large table covered by a cloth designed and wrought by the same restless hands. Neatly painted chairs were ranged around the walls, and beneath the low broad window stood a hard, unyielding couch upon which lay a thick blanket and several bright pillows stuffed with sweet-grass.

At the casement were spotless curtains, standing out stiffly like starched skirts on prim little girls, and behind them rows of tin cans in which were growing gorgeous begonias and geraniums pressed against the glistening glass, like curious children peering into the black outer world. So had Jo's inarticulate life developed and expressed itself in this home-like room, while her mind had matured and her thoughts deepened. Then her eyes travelled to the winding stairway in the farthest corner. Her gaze kept to the strip of yellow paint in the middle of the white steps. It mounted higher and higher. Above was the upper chamber, the Waiting Room!

Long years ago, while serving in Madame Longville's home, Jo had conceived an ambition that had never really left her through all the time that had intervened. Some day she would have a boarder! Not upon such terms as the Longvilles accepted, however.

Her boarder was not merely to pay and pay in money, but he would be to her an education, a widening experience. She, alone, would reap the reward of the toil she expended upon him. And so with this in mind she had furnished the upper chamber, bit by bit, and had calculated over and again the proper sum to charge for the benefits to be derived and given.

"And now," said Jo, panting a little as if her eyes mounting the stairs had tired her. "Come summer I will get my boarder, but love of heaven! What price shall I set?"

The wind was rising and the pine trees were making that sound that always reminded Jo of poor Cecile's wordless moan.

Something seemed to press against the door. Nick started and bristled.

"Who's there?" demanded Mam'selle. There was no reply—only that tense pressure that made the panels creak.

CHAPTER III

MAM'SELLE DOES NOT BUY A HUSBAND

The tall clock in the kitchen struck eight in a sharp, affrighted way much as a chaperone might have done who wished to call her heedless charge to the demands of propriety.

Eight o'clock in Point of Pines meant, under ordinary conditions, just two things: house and bed for the respectable, Dan's Place—a reeking, dirty tavern—for the others.

And while Jo Morey's door creaked under the unseen pressure from without, Pierre Gavot and Captain Longville smoked and snoozed by the red-hot stove at Dan's, occasionally speaking on indifferent subjects.

These two men disliked and distrusted each other, but they hung together, drank together; for what reason who could tell? Gavot had eaten earlier in the day at the Longville house and during the meal the name of Jo Morey had figured rather prominently. However, Gavot had paid little heed, he had little use for women and no interest, whatever, in an ugly one. A long past French ancestry had given Gavot as it had Longville a subtle suavity of manner that somewhat cloaked his brutality, and he was an extremely handsome man of the big, dark type.

Suddenly now, in the smoky drowsiness of the tavern, Mam'selle Morey's name again was introduced.

"Mam'selle! Mam'selle!" muttered Pierre impatiently; "I tire of the mention of the black Mam'selle. Such a woman has but two uses: to serve while she can, to die when she cannot serve."

"But her service while she can serve, that has its value," Longville retorted, puffing lustily and blowing the smoke upward until it quite hid his eyes, no longer sleepy, but decidedly keen.

"The Mam'selle has money, much money," he went on, "that and her service might come in handy for you and Tom."

And now Pierre sat a little straighter in his chair.

"Me and Tom?" he repeated dazedly. "You mean that I get the Mam'selle to come to my—my cabin and work?"

Somehow this idea made Longville laugh, and the laugh brought a scowl to Pierre's face.

"Tom will be going off some day," the Captain said irrelevantly, "then what?"

"Tom will stick," Gavot broke in, "I'll see to that. Break the spirit of a woman or child and they stick."

But as he spoke Gavot's tone was not one of assurance. His boy Tom was not yet broken, even after the years of deprivation and cruelty, and lately he had shown a disposition for work, work that brought little or no return. This worried Gavot, who would not work upon any terms so long as he could survive without it.

"You can't depend upon children," Longville flung back, "a woman's safer and handier, and while the Mam'selle, having money, might not care to serve you for nothing, she might——" here the Captain left an eloquent pause while he leered at his brother-in-law seductively. Gradually the meaning of the words and the leer got into Gavot's consciousness.

"Good God!" he cried in an undertone, "you mean I should—marry the ugly Mam'selle Morey?" But even as he spoke the man gripped the idea savagely and, with a quickness that always marked the end of his muddled conclusions, he began to fix it among the possibilities of his wretched life.

"She needs a man to handle her money," Longville was running on. He saw the spark had ignited the rubbish in Gavot's mind. "And she's a powerful worker and saver. She cooks like an angel; she studies that art as another might study her Bible. She has a mind above most women, but properly handled and with reason——"

"What mean you, Longville, properly handled and with reason? Would any man marry Mam'selle?"

"A wise man might—yes," Longville was leading his brother-in-law by the most direct route, but he smiled under cover of the smoke. The Morey money in Gavot's hands meant Longville control in the near future. So the Captain smiled.

"She'd marry quick enough," he rambled on, refilling his pipe. "A man of her own is a big asset for such a woman as the Mam'selle. And then the law stands by the husband; woman's wit does not count."

Gavot was not heeding. His inflamed imagination had outstripped Longville's words. Once he had mastered the physical aspect of the matter, the rest became a dazzling lure. Never for an instant did he doubt that Jo Morey would accept him. The whole thing lay in his power if——

"She's old and ugly," he grunted half aloud.

"What care you?" reassured Longville, "ugliness does not hamper work, and her age is an advantage."

"But, what was that Langley story——?" Pierre was groping back helplessly.

Point of Pines had its moral standards for women, but it rarely gossiped; it stood by its own, on general principles, so long as its own demanded little and was content to take what was offered.

"That? Why, who cares for that after all this time?" Longville spoke benignly. "If Langley left the Mam'selle with that which no woman, without a ring, has a right to, she was keen enough to rid herself of the burden and cut her own way back to decent living. She has asked no favours, but she'd give much for a man to place her among her kind once more."

A deep silence followed, broken only by the guzzling and snoring of the other occupants of Dan's Place.

Suddenly Gavot got to his feet and reached for his hat. His inflamed face gave evidence of his true state.

"Back to Mastin's Point?" Longville asked, stretching himself and yawning.

"No, by heaven! but to Mam'selle Jo Morey's."

This almost staggered Longville. He was slower, surer than his wife's brother.

"But your togs," he gasped, "you're not a figure for courting."

"Courting?" Gavot laughed aloud. His drinking added impetus to every impulse and desire. "Does Mam'selle have to have her pill coated? Will she not swallow it without a question?"

"But 'tis late, Gavot——"

"And does the chaste Mam'selle keep to the early hours of better women?"

"But to-morrow—the next day," pleaded Longville, seeking to control the situation he had evolved. He feared he might be defeated by the force he had set in motion.

"No, by heaven, to-night!" fiercely and hoarsely muttered Gavot, "to-night or never for the brown and ugly Mam'selle Jo. To-night will make the morrows safe for me. If I stopped to consider, I could not put it through."

With that Gavot, big, handsome, and breathing hard, strode from the tavern and took to the King's Highway.

The wind rushed past him; pushed ahead; pressed at Jo's door with its warning. But she did not speak, and only when Gavot himself thumped on the panel was Jo roused from her revery and Nick from his puppy dreams.

"Who's there?" shouted Mam'selle, and clumped across the floor in her father's old boots. She slipped on one of the rugs and slid to the entrance before regaining her balance.

"It is I, Mam'selle, I, Pierre Gavot."

Jo opened the door at once.

"Well," she said with a calmness and serenity that chilled the excited man, "it's a long way from here to Mastin's and the hour's late, tell your business and get on your way, Pierre Gavot. Come in, sit by the fire. My, what a wind is stirring. Now, then—out with it!"

This crude opening to what Pierre hoped would be a dramatic scene, sweeping Jo Morey off her feet, nonplussed the would-be gallant not a little. He sat heavily down and eyed Nick uneasily. The dog was sniffing at his heels in a most suspicious fashion. Every hair of his body was on guard and his eyes were alert and forbidding.

"Well, Pierre Gavot, what is your errand?"

This did not improve matters and a shuffling motion toward Nick with a heavy boot concluded the investigation on the dog's part. Nick was convinced of the caller's disposition; he showed his teeth and growled.

"Come, come, now," laughed Mam'selle, whistling Nick to her, "you see, Pierre Gavot, I have a good care-taker. That being settled, let us proceed." Then, as Gavot still shuffled uneasily, she went on:

"Maybe it is Tom. I heard the other day that 'twas whispered among your good friends that unless you did your duty by Tom, there would be a sum raised to give the poor lad a chance—away from his loving father." Jo laughed a hard laugh. She pitied Tom Gavot with her woman-heart while she hated the man who deprived the boy of his rights.

Gavot shut his cruel lips close, but he controlled the desire to voice his real sentiments concerning the bit of gossip.

"Indeed there is no need for my neighbours showing their hate, Mam'selle. Tom's best good is what I'm seeking. He's young, young enough to be cared for and watched. I'm thinking more of Tom than of myself, and yet I ask nothing for him from you, Mam'selle Jo."

"So, Gavot! Well, then, I am in the dark. Surely you could ask nothing of me for yourself!"

Again Pierre was chilled and inclined to anger. All his fire and fury were deserting him; his intention of taking Jo by storm was disappearing; almost he suspected that she was getting control of the situation. He slyly looked at her dark, forbidding face and weighed the possibilities of the future. Jo, he realized, was secure now in her unusual independent position. Once let him, backed by the good law, which covers the just and the unjust husband with its mantle of authority, get possession of her future and her body, he'd manage—ah! would he not—to utilize the one and degrade the other!

"Mam'selle, I come to you as a lone and helpless man. Mam'selle, I must—Mam'selle, I want that you should live the rest of the time of our lives—with me!"

Jo was aroused, frightened. She turned her luminous eyes upon the man.

"You—you are asking me to marry you, Pierre Gavot?"

Gavot, believing that the meaning of his visit had at last brought her to his feet at the first direct shot, replied with a leer:

"Well, something like that, Mam'selle."

And now Jo's brows drew close; the eyes were darkened, the lips twitched ominously. As if to emphasize the moment, Nick, abristle and teeth showing, snarled gloomily as he eyed Gavot's feet.

"Something like that?" repeated Jo with a thrill in her tones. "You insult me, Gavot! Something like that. What do you mean?"

"God of mercy, Mam'selle," Gavot was genuinely alarmed, "I ask you to—be—my wife."

Jo leaned back in her chair. "I wish you'd talk less of the Almighty, Gavot. I reckon the Lord can speak for himself, if men, specially such men as you, get out of his way. It sickens me to have to find the meaning of God through—men. And you ask me to be your wife? You. And I was with Margot when she died!"

Gavot's eyes, for an instant, fell.

"Margot was out of her head," he muttered. "She talked madness."

"It was more truth than fever, Gavot. Her tongue ran loose—with truth. I know, I know."

"Well, then, Mam'selle, 'tis said a second wife reaps the harvest the first wife sowed. I have learned, Mam'selle Jo."

"Almost it is a greater insult than what I first thought!" Jo sighed sadly. "But 'tis the best you have to offer—I should not forget that—and some women would lay much stress on the chance you are offering me. One thing Margot said, Gavot, has never passed my lips until now—though often I've thought of it. When she'd emptied her poor soul of all that you had poured into it, when she had shriven herself, and was ready to meet her God, the God you had never let her find before because you got in between, she looked at Tom. The poor lad sat huddled up on the foot of the bed watching his mother going forth. 'Jo,' she whispered, 'when all's said and done, it paid because of Tom! When I tell God about Tom and what Tom meant, He'll forgive a lot else. He does with women.'"

Gavot dared not look up, and for a moment a death-like silence fell in the hot, tidy room. Jo looked about at her place of safety and freedom and wondered how she could hurry the disturbing element out.

Just then Gavot spoke. He had grasped the only straw in sight on the turgid stream.

"Mam'selle, you're not too old yet to bear a child, but you'll best waste no time." And then he smiled a loathsome smile that had its roots in all that had soiled and killed poor Margot Gavot's life. Jo recoiled as if something unclean were, indeed, near her.

"Don't," she shuddered warningly, "don't!" Then quite suddenly she turned upon the man, her eyes blazing, her mouth twisted with revolt and disdain.

"I wonder—if you could understand, if I showed you a woman's heart?" she asked with a curious break in her voice. "Long, long years I've ached to show the poor, dead thing lying here," she put her work-hardened hands across her breast, "to someone. There have been times when I have wondered if the telling might not help other women in Point of Pines; might not make men see plainer the wrong they do women; but until now there has never been any one to tell."

Expression was crying aloud, and the incongruity of the situation did not strike Jo Morey in her excitement.

"You've got to hear me out, Pierre Gavot," she went on. "You've come, God knows why, to offer me all that you have to give in exchange for—well! I'm going to give you all that I have to give you—all, all!

"There was a time, Gavot, when I longed for the thing that most women long for, the thing that made Margot take you—you! She knew her chances, poor soul, but you seemed the only way to her desires, so she took you!

"'Tis no shame to a woman to want what her nature cries out for, and the call comes when she's least able to understand and choose. Here in Point of Pines a girl has small choice. It is all well enough for them who do not know to talk of love and the rest. The burning desire in man and woman is there with or without love; it's the mercy of God when love is added. I knew what I wanted, all that counted to me must come through man, and love—my own love—sanctified everything for me. I did not understand, I did not try to, I was lifted up——"

Jo choked and Gavot twisted uneasily in his chair. This was all very boring, but he must endure it for the time being.

"I—I was willing to play the game and take my chances," Jo had got control of herself, "and I never feared, until it was forced upon me, that my ugliness stood in the way. All that I had to offer, and I had much, Gavot, much, counted as nothing with men because their eyes were held by this face of mine and could not see what lay behind.

"Perhaps that was God's way of saving me. I thought that for the first when I saw Margot dying.

"I had my love killed in me, but the desire was there for years and years; the longing for a home of my own and—children, children! After love was gone, after I staggered back to feeling, there were times when I would have bartered myself, as many another woman has, for the rights that are rights. But, since they must come by man's favour, I was denied and starved. Then the soul died within me, first with longing, then with contempt and hatred. By and by I took to praying, if one could call my state prayer. I prayed to the God of man. I demanded something—something from life, and this man's God was just. He let me succeed as men do, and this, this is the result!"

Jo flung her arms wide as if disclosing to Gavot's stupid eyes all that his greed ached to possess: her fields and barns; her house and her fat bank account. But the man dared not speak. He seemed to be confronting an awful Presence. He looked weakly at Jo Morey, estimating his chances after she had had her foolish way with him. Vaguely he knew that in the future this outburst of hers would be an added weapon in his hand; not even yet did he doubt but what he would gain his object.

"It's all wrong," Jo rushed on, seemingly forgetting her companion, "that women should have to wait for what their souls crave and die for until some man, looking at their faces, makes it possible. A pretty face is not all and everything: it should not be the only thing that counts against the rest. Why, the time came, Gavot, when a man meant nothing to me compared with—with other things."

The fire and purpose died away. The outbreak, caused by the day's experience, left Jo weak and trembling. She turned shamed and hating eyes upon Gavot. She had let loose the thought of her lonely years.

"And now you come, you!" she said, "and offer me, what?"

Pierre breathed hard, his time had come at last.

"Marriage, Mam'selle. I'm willing to risk it."

"Marriage! My God! Marriage, what does that mean to such as you, Pierre Gavot? And you think I would give up my clean, safe life for anything you have to offer? Do men think so low of women?"

Gavot snarled at this, his lips drew back in an ugly smile.

"God made the law for man and woman, Mam'selle——"

"Stop!" Jo stood up and flung her head back. "Stop! What do such as you know of God and his law? It's your own law you've made to cover all your wickedness and selfishness and then you—you label it with God's mark. But it's not God's fault. We women must show up the fraud and learn the true from the false. Oh! I've worked it out in my mind all these years while I've toiled and thought. But, Gavot, while we've been talking something has come to me quite clear. Not meaning to, you've done me a good turn.

"There's one way I can get something of what I want, and it's taken this scene to show me the path. Come to-morrow. You shall see, all of you, that I'm not the helpless thing you think me. Thinking isn't all. When we've thought our way out, we must act. And now get along, Gavot, the Lord takes queer ways and folks to work out his plans. Good-night to you and thank you!"

Pierre found himself on his feet and headed toward the door which Jo was holding open.

Outraged and flouted, knowing no mercy or justice, he had only one thing to say:

"Curse you!" he muttered; "curse and blast you."

Then he slunk out into the wild, black night.

A woman scorned and a man rejected have much in common, and there was the explanation to the Longvilles to be faced!

CHAPTER IV

BUT MAM'SELLE MAKES A VOW

After Mam'selle was certain that Gavot was beyond seeing her next move, she flung the door wide open, letting the fresh, pure night air sweep through the hot room.

Nick sprang to his feet but, deciding that the change in temperature had nothing to do with the late guest, he sidled over to Jo who stood on the threshold and pushed his questioning nose into her hand.

"Come, old fellow," she said gently, "we do not want sleep; let us go out and have a look at the sky. It will do us both good."

Quietly they went forth into the night and stood under a clump of pine trees back of the house and near the foot of the hill.

The clouds were splendid and the wind, like a mighty sculptor, changed their form and design moment by moment. They were silver-edged clouds, for a moon was hidden somewhere among them; here and there in the rifts stars shone and the murmuring of the pines, so like Cecile's cry, touched Mam'selle strangely. It seemed to her, standing there with Nick beside her, that something of the old, happy past was being given back to her. She smiled, wanly, to be sure, and tears, softer than had blurred her eyes for many a year, wet her lashes. In a numb sort of way she tried to understand the language of the night and the hour; it was bringing her peace—after all her storms. It was like having passed from a foul spot in a dark valley, to find oneself in a clear open space with a safe path leading——? With this thought Jo drew in her breath sharply. As surely as she had ever felt it in her life, she now felt that something new and compelling was about to occur. The meaning and purpose of her life seemed about to be revealed. Jo was a mystic; a fatalist, though she was never to realize this. Standing under the wind-swept sky she opened her arms wide, ready to accept! And then it came to her in definite form, the thought that had arisen during her talk with Gavot. She had said that she could have done without man if only the rest had been vouchsafed.

Well, then, what remained? She had house and lands and money. She might be denied the travail and mystery of having a child, but there were children; forgotten, disinherited children. They were possible, and if she accepted what was hers to take, her life need not be aimless and cheerless. She might yet know, vicariously, what her poor soul had craved.

A wave of religious exaltation swept over Jo Morey. Such moments have been epoch-making since the world began. The shepherds on Judea's plains, caught in the power of this emotion, lifted their eyes and saw the guiding star that led them to the Manger and the world's salvation! Down the ages it has turned the eyes of lesser men and women to their rightful course, and it now pointed Jo Morey to her new hope!

"I will adopt a child!" she said aloud and reverently as if dedicating herself. "A man child."

And then, in imagination, she followed the star.

Over at St. Michael's-on-the-Rocks there was a Catholic institution where baby driftwood was taken in without question. St. Michael's was a harbour town boasting a summer colony. Women there, as elsewhere, paid for too much faith or unsanctified greed, and the institution was often the solution of the pitiful outcome.

Jo had repeatedly contributed to the Home. She had no affiliation with the church that supported it, but the priest of Point of Pines had gained her respect and liking, and for his sake she had secretly aided causes that he approved. Tom Gavot, for instance, and the St. Michael's institution.

"Come, Nick," she said presently, "we'll sleep on it."

All night Mam'selle tossed about on her bed trying to argue herself into common sense. When she came down from the heights her decision appeared wild and unreasonable.

What would people say?

Rarely did Jo consider this, but it caught and held her now. Her hard, detached life had set her apart from the common conditions of the women near her. She was in many ways as innocent and guileless as a child although the deepest meanings of suffering and sorrow had not been hidden from her. That any one suspected her of being what she was not, had never occurred to her. She had shrunk from everyone at the time of Langley's desertion, because she neither wanted, nor looked for, sympathy and understanding. She was grateful for the indifference that followed that period of her life, but never for a moment had she known of that which lay hidden in the silence of her people.

Poor Jo! What Point of Pines was destined to think was impossible for her to conceive, because her planning was so wide of the reality that was to ensue. Tossing and restless, Jo tried to laugh her sudden resolve to scorn, but it would not be scorned either by reason or mirth.

"Very well!" she concluded for the second time, "I'll adopt a child, a man child! No girl things for me. I could not watch them straining out for their lives with the chance of losing them. A man can get what he wants and I'll do my best, under God, to make him merciful."

Toward morning Jo slept.

The next day she cooked and planned as calmly as if she were arranging for an invited guest. All her excitement and fire were smothered, but she did not falter in her determination. She explained to Nick as she tossed scraps to him. Nick was obligingly broad in his appetite and tastes, bones and bits of dough were equally acceptable, and he patted the floor thankfully with his sturdy little tail whenever Jo remembered him.

"We'll take it as a sign, Nick," she said, "that what I'm trying to do is right if there is at St. Michael's a man-thing, handsome and under a year old. We must have him handsome, that's half of the battle, and he must be so young that he can't remember. I want to begin on him.

"Now I'll bet you, Nick, that the Home is bristling with girl children and we'll have none of them."

Nick thumpingly agreed to all this but kept his eye on a plate of cookies that Mam'selle was lavishly sugaring. Nick did not spurn scraps but, like others, he yearned for tidbits.

All day Jo worked, cooking and setting her house in order.

Late in the afternoon she contemplated cutting a door between the two north chambers, her own and the one her father had used, which had never been occupied since.

"The child will soon need a place of his own," mused Jo, already looking ahead as a real mother might have done. Suddenly she started, recalling for the first time since before Pierre Gavot's diverting call her ambition concerning a boarder.

"Well, the boarder will have to wait," she thought, "they hate babies, and boys are terribly noisy and messy. I'll take a boarder when the lad goes away to school. I'll need company then."

By nightfall the little white house was spotless and in order. The fragrance of cooking mingled with the odour of wood fire was soothing to Jo's tired nerves; it meant home and achievement.

"I'll not let on about the child," she concluded just before she went to sleep. "When the doors of St. Michael's close on a child going in or out, they close, and that is the end of it. If folks care to pry it will give them something to do and keep them alive, but it's little they'll get from the Sisters or me.

"I'm a fool, a big fool, but I can pay for my folly and that's more than many women can do."

Early on the following morning Jo set forth in her broad-bellied little cart in which were a hamper of goodies for the waifs of St. Michael's, and a smaller basket containing Jo's own midday meal. Jo, herself, sat on the shaft beside the fat Molly and bobbed along in the best of spirits.

"You're to watch the place, Nick," she commanded, "and if he returns, you know who, just save a nip of him for me, that's a good beastie."

With this possibility of adventure, Nick had to be content.

Madame Longville saw Jo pass and remarked to the Captain who was eating the pancakes his wife was making:

"There goes Mam'selle, and so early, too; somehow she doesn't look as if she had taken up with Pierre."

"How does she look?" asked the Captain with his mouth full.

"Sort of easy and cheerful."

"Fool," muttered Longville and reached for more cakes. "Is she afoot?"

"No. She's in the little cart and it's empty."

"She's going to fetch Gavot, bag and baggage." Longville felt that he had solved the problem. "It takes a woman like Mam'selle to clinch a good bargain."

Then Longville laughed and sputtered.

"It was a good turn I did for your rascal brother when I turned him on to Mam'selle," he continued. "I took the matter in my own hands."

"I'm glad you did," Marcel returned, "but all the same Jo Morey doesn't look as if she had taken up with Pierre."

The repetition irritated Longville and again he muttered "fool!" then added "damn fool" and let the matter rest.

But Jo was out of sight by that time and seemed to have the empty world to herself. And what a world it was. The wind of the past few hours had swept the sky clear of clouds and for that time of year the day was warm.

Presently Jo found herself singing: "A la Claire Fontaine" and was surprised that it caused her no heartache. So grateful was she for this, that she dismounted and stood under one of the tall crosses by the wayside and prayed in her silent, wordless fashion, recalling the years that were gone as another might count the beads of a rosary. Her state of mind was most perplexing and surprising, but it was wonderful. What did it matter, the cause that resulted in this sense of freedom, and, at the same time, of being used and controlled? Jo felt herself a part of a great and powerful plan. Surely there is no truer freedom than that. At noon the roofs of St. Michael's were in plain sight over the pastures; by the road was a delectable pine grove with an opening broad enough to drive in, so in Jo drove. She unhitched Molly and fed her, then taking her own food to a log lying in the warm sunlight, she laid out her feast and seated herself upon the fragrant pine needles. She was healthfully hungry and thirsty and, for a few minutes, ate and drank without heeding anything but her needs. Then a stirring in the bushes attracted her attention. She raised her eyes and noted that the branches of a crimson sumach near the road were moving restlessly. Thinking some hungry but shy creature of the woods was hiding, Jo kept perfectly still, holding a morsel of food out enticingly.

The branches ceased trembling, there was no sound, but suddenly Jo realized that she was looking straight into eyes that were holding hers by a strange magnetism.

"What do you want?" she asked. "Who are you?"

There was no reply from the flaming bush, only that stare of fright and alertness.

"Come here. I will not hurt you. No one shall hurt you."

Either the words, or actual necessity, compelled obedience: the branches parted and out crawled a human figure covered by a coarse horse blanket over the dingy uniform of St. Michael's.

For a moment Jo was not sure whether the stranger were a boy or girl, for a rough boyish cap rested on the head, but when the form rose stiffly, tremblingly she saw it was that of a girl. She was pale and thin, with long braids of hair known as tow-colour, a faintly freckled face, and marvellous eyes. 'Twas the eyes that had caught and held Jo from the start, yellow eyes they were and black fringed. They were like pools in a wintry landscape; pools in which the sunlight was reflected.

"I—I am starving to death," said the girl advancing cautiously, slowly.

"Sit down and eat, then," commanded Jo, and her throat contracted as it always did when she witnessed suffering. "After you've had enough, tell me about yourself."

For a few minutes it seemed as if there were not enough food to satisfy the hungry child. She ate, not greedily or disgustingly, but tragically. At last, after a gulp of milk, she leaned back against a tree and gave Jo a grateful, pitiful smile.

"And now," said Jo, "where did you come from?"

"Over there," a denuded chicken bone pointed toward the Home.

"You live there?"

"I used to. I ran away last night. I've run away many times. They always caught me before."

The words were spoken in good, plain English. For this Jo was thankful. French, or the composite, always hampered her.

"Where were you last night?" she asked.

"Here in the woods."

Remembering the manner of night it was, Jo shivered and her face hardened.

"Were they cruel to you over there?" she said gruffly.

"Do you mean, did they beat me? No, they didn't beat my body, but they beat something else, something inside of me, all out of shape. They tried to make me into something I am not, something I do not want to be. They, they flattened me out. They were always teaching me, teaching me."

There was a comical fierceness in the words. Jo Morey recognized the spirit back of it and set her jaw.

"I never saw you at the Home," she said; "I've often been there."

"They only show the good ones—the ones they can be sure of. I took care of the babies when I wasn't being punished, locked up, you know. You see, I learned and could teach."

"They locked you up?" Mam'selle and the child were being drawn close by ties that neither understood.

"Yes, to keep me from running away. You're not going to tell them about me, are you?"

The wonderful eyes seemed searching Jo's very soul.

"No. But where are you going?"

"I'm, I'm looking for someone." As she spoke the light vanished from the yellow eyes, a blankness spread over the pale, thin face.

"Looking for whom?"

"I do not know."

"What is your name?" Jo was struck by the change in the girl, she had become listless, dull.

"I do not know. Over there they call me Marie, but that isn't my name."

"I can't let you go off alone by yourself," Jo was talking more to herself than to the girl.

"Then, what are you going to do with me? Please try to help me. You see I was very sick once and I—I cannot remember what happened before that, but it keeps coming closer and closer and pressing harder and harder—here." The girl put her hand to her head. "Once in awhile I catch little bits and then I hold them close and keep them. If I could be let alone I think soon I would remember."

The pleading eyes filled with tears, the lips trembled.

Now the obvious thing to do, Jo knew very well: she ought to bundle the girl into the cart and drive as fast as possible to the Home. But Mam'selle Jo knew that she was not going to do the obvious thing, and before she had time to plan another course she saw two black-robed figures coming across the pasture opposite. The girl saw them, too, and rushed to Jo. She clung to her fiercely and implored:

"God in heaven, save me! If they get me, I will kill myself."

The appeal turned Jo to stone.

"Get in the cart," she commanded, "and cover up in the straw."

The two Sisters from the Home were in the road as Jo bent to gather up the debris of the meal.

"Ah, 'tis the Mam'selle Morey," said the older Sister. "You were coming to St. Michael's perhaps, with your goodly gifts?" The words were spoken in pure French.

"I was coming, Sister—to—to adopt a child!"

The blunt statement, in bungling words, made both Sisters stare.

"'Tis like your good heart to think of this thing, Mam'selle Morey. Another day we will consider it."

"Why not to-day, Sister? My time is never empty. I want a boy, very young and—and good to look at."

"Oh, but Mam'selle Morey, one does not adopt a child as one does a stray cat. Another day, Mam'selle, and we will consider gladly, but to-day——"

"What of to-day, Sister?"

"Well, one of our little flock has strayed, a child sadly lacking but dearly loved; we must find her."

"She has been gone long?" Jo was moving to the cart with her basket and bottles.

"She has just been missed. We will soon find her."

Jo's hand, searching the straw, was patting the cold one that trembled beneath her touch. "May I give you a lift along the road?" she asked grimly, the humour of the thing striking her while she reassured the hidden girl by a whispered word.

"Thanks, no, Mam'selle. We will not keep to the roads. The lost one loved the woods. She'd seek them."

Jo waited until the Sisters had departed, her hand never having left the trembling one beneath hers.

"You are going to—to take me with you?" The words came muffled, from the straw.

"Yes."

"And where?"

"To Point of Pines."

"What a lovely name. And you, what may I call you?"

"Jo, Mam'selle Jo."

"Mam'selle Jo. That is pretty, too, like Point of Pines. How kind you are and good. I did not know any one could be so good."

"Lie down now, child, and sleep."

Jo was hitching Molly to the cart; her hands fumbled and there was a deep fire in her dark eyes.