PHOTOGRAPH OF THE AUTHOR TAKEN IN THE YARD OF THE PRISON IN BERLIN, JUNE, 1917

My Three Years

In a

German Prison

BY

HON. HENRI BELAND, M.D., M.P.

Illustrated with photographs specially secured

in Belgium and Germany

TORONTO

WILLIAM BRIGGS

1919

PRINTED IN

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO MY OLD MOTHER

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | It Is War | 1 |

| II | The German Tavern-Keeper and the Brabançonne | 9 |

| III | “Thank You” | 13 |

| IV | Doing Hospital Work | 14 |

| V | The Capture of Antwerp | 25 |

| VI | The Exodus | 33 |

| VII | A Day of Anguish | 39 |

| VIII | The Germans Are Here | 46 |

| IX | A German Host | 53 |

| X | The Word of a German | 59 |

| XI | British Citizens | 64 |

| XII | Matters Become Complicated | 69 |

| XIII | A Desolate Major | 77 |

| XIV | In Germany | 87 |

| XV | The Stadtvogtei | 91 |

| XVI | Life in Prison | 98 |

| XVII | Meals à la Carte | 105 |

| XVIII | Acting Jail Physician | 116 |

| XIX | Interesting Prisoners | 127 |

| XX | Maclinks and Kirkpatrick | 137 |

| XXI | A Swiss and a Belgian | 144 |

| XXII | Sensational Escapes | 160 |

| XXIII | Hope Deferred | 170 |

| XXIV | A Colloquy | 176 |

| XXV | Incidents and Observations | 185 |

| XXVI | Talk of Exchange | 195 |

| XXVII | Towards Liberty | 203 |

| XXVIII | Some Recollections | 213 |

| XXIX | Other Reminiscences | 224 |

| XXX | An Alsatian Non-Commissioned Officer | 242 |

| XXXI | In Holland and in England | 252 |

| XXXII | The Militarists and the Militarized | 268 |

| PAGE | |

| The Author | Frontispiece |

| The Digue at Middelkerke | 12 |

| Madame Beland at Starrenhof | 38 |

| Feeding Poor Boys at Capellen | 56 |

| Group of German Officers | 68 |

| A Sample of German Perfidy (letter) | 80 |

| Dr. Beland and Fellow-prisoners | 144 |

| Ludendorf and Von Buelow | 256 |

It was the 26th of July, 1914. My wife and I were walking leisurely in the park of a village in the Pyrenees, the sun shedding its warm, quickening rays in the Valley of the Gave when, suddenly, a newsboy approached us carrying under his arms a bundle of newspapers, and crying at the top of his voice, “War! War! It is War!”

I stopped him, asking at the same time, “What war?”

“Why, the war between Austria and Serbia. The paper will give you all the details,” he answered.

As a matter of fact, the paper he was selling, “La Liberte du Sud-Ouest,” contained the text of the now and forever famous ultimatum of Austria-Hungary to the little Balkan power.

The following day, at each important railway station we passed through on our way from Bordeaux to Paris, fresh editions of the French newspapers were brought to us, each containing strong, passionate comments on the diplomatic document which threatened the peace of Europe.

In the compartment of the train where we sat the conversation was animated. That Austria was at her perfidious tricks again was the consensus of opinion generally, although the best informed ones realized that it was ambitious and treacherous Germany which inspired Austria.

We stayed a few days in Paris on our way to Antwerp. Our impression of the French capital was that, even in that diplomatic torment, the city maintained a remarkable calmness. Of course, the sole topic of discussion in the cafés, on the[3] boulevards, in the busses and the trams was the war, but there appeared to be a complete absence of that agitation which one who has visited Paris in normal times is well aware of.

I wished to send a telegram to Belgium, but was told that all lines had been taken over by the military authorities and that my message would probably be delayed a full day or more.

On the day of my leaving Paris for Antwerp I paid a visit to the Honorable Mr. Roy, Canadian High Commissioner, and asked him what he thought of the diplomatic situation. The eminent representative of Canada expressed grave anxiety, and said he feared a declaration of war between Germany and France was imminent.

At noon the same day my wife and I started for Antwerp on the Paris-Amsterdam fast express, passing through the territory of France and Belgium which within two months was to be the scene of horrors of war that have appalled the whole world. Far were we then from thinking that those cities–actual beehives of[4] industry–and those fine farm lands, bearing fast-ripening crops and inviting the harvester’s scythe, would be within a few weeks devastated, pillaged, plundered and burned.

The agitation was great in Antwerp; the city yeomanry had been called to arms, and on this same evening, July 30, rumors were already in circulation that Germany had sinister intentions and that she was actually preparing to violate Belgium’s neutrality.

The mere mention of such an act, which meant trampling upon all international laws, stirred the Belgian people to a high pitch of indignation. The same evening we arrived at the village of Capellen, situated six miles north of Antwerp, on the Antwerp-Rotterdam highway.

On the following day, Saturday, August 1, we started for Brussels, en route to Ostend, and thence to Middelkerke, a charming seaside resort, where we were to spend the rest of the summer season. Middelkerke is situated half way between Ostend and Nieuport, recently evacuated by the[5] Germans, and which has been the division line between the German and the Belgian armies for four years.

An incident of which I have a personal knowledge shows that Germany intended to violate Belgium’s neutrality from the outset of the imbroglio between Austria and Serbia. We were about to leave Brussels for Ostend and had already boarded the train when a well-known citizen of Ghent and his wife entered the already crowded compartment where we sat. They apologized for their intrusion, but in such pressing times one had to travel as best one could, and it was with sincerity that we accepted the apologies of the couple for intruding in such a way in the compartment allotted to us.

After exchanging cards, the gentleman related that the day before he and his wife were returning in an automobile from a tour in Germany when, near the frontier, they were stopped by German military. Their papers were examined, but notwithstanding their credentials as Belgian subjects, and proof that they were on their[6] way home from a holiday trip, their automobile was seized and they were compelled to stay the night in a hotel. The room assigned to them was on the ground floor where they were unable to sleep owing to the tramp, tramp, tramp of German regiments marching to the German border. The troops were singing “Deutschland über Alles,” and the rumble of the drums never ceased from early evening until the following morning. This happened in a village situated within two or three kilometers from the Belgian frontier, on the night of July 31. Germany’s ultimatum to Belgium was not presented until two days later.

On the journey from Brussels to Ostend, which was much delayed owing to the throng which, moved to fear by all kinds of wild rumors, were eager to reach home, another incident occurred:

In the section of the train where my wife and I were seated were four other passengers in addition to the couple I have already referred to. They were three Austrian ladies–a mother and her two[7] daughters–and a man–a well-known owner of racing horses from Charleroi. The three ladies apparently belonged to the highest society. They were on their way to Ostend where they intended taking a steamer for England, where the mother said her son was a student.

The conversation between the sportsman and the three ladies turned on the tenseness of the situation then existing between Austria and Serbia. The man was very outspoken in his denunciation of Austria. The elder lady, naturally, defended her country.

“The Serbians,” the man replied, “may not be above suspicion, but there are other things equally suspicious, and this war which you are about to declare on a small country may be the act of the Austrian Government directed to extend its territory in the Balkans. It is dictated above all by the Autocrat at Potsdam, who is holding the stakes and will direct every move to satisfy his immoderate ambition.”

The lady, I must say, while moderate in her retorts, was nevertheless obstinate in[8] denying that Germany had anything to do with the Balkan imbroglio, but the racing man was also obdurate, and with what turned out to be extraordinary accuracy he predicted that within a few days France, Russia and Great Britain would take up the cudgels on behalf of Serbia and enter the fray.

The conversation was still going on when the trainman announced Ostend.

Great agitation reigned on the beach at Middelkerke on August 3, 1914. The newspapers had just published the text of the Kaiser’s ultimatum to the Belgian Government. The indignation was at its highest pitch. The population could not conceive that the German Emperor, who had been entertained in Brussels a few months previously, who had been the guest of the King of the Belgians and the Belgian nation, could stoop so low as to insult both King and people. From the villa where we lived we could watch the crowds congregate on the beach. From time to time groups would leave the main body and, forming into a procession, would march to the front of a tavern, whose owner and keeper was a German. On the front of[10] this tavern were three large signs advertising the merits of a certain brew of German beer. The crowd had to give vent to its indignation in some way, and the German signs were a tempting target for the irate population. It took but a minute to pull down the lower sign. The use of a ladder was required to pull down the one above. While this rather comical performance was going on, the surging crowd yelled and hollered, and called upon the voluntary wreckers to pull down the topmost sign which adorned the front of the third story. The ladder was too short. When this was realized, a delegation was sent to the tavern-keeper to demand that he himself go up and pull down the obtrusive sign.

At first the man demurred, but seeing the increasing excitement he decided to obey the summons. A few seconds afterwards his rubicund face appeared at a window near the roof of the building and, not without difficulty, he succeeded in pulling down the sign, while the whole beach rang with the echoes of the crowd singing and[11] a brass band playing Belgium’s national anthem, “La Brabançonne.”

The following morning the proud and noble reply which the King of Belgium made to Germany’s ultimatum was published. A herald read the royal proclamation at all corners of the streets leading to the beach, amid the acclamations of the younger folks. Meanwhile sinister rumors were circulating. Some were to the effect that Vise was burning; others that Argenteau had been destroyed; that civilians had been executed; that devastation and terror reigned in the region situated east of the Meuse river; that the Germans, without even waiting a reply to their provoking summons to Belgium, had invaded Belgian territory–which fact the reader now knows to be true–according to the statement made to me a few days previously on that Ostend train by the couple returning to Ghent from a trip through Germany.

I particularly recall the anguish of a brave old lady, Mrs. Anciault, who owned and was staying at a villa at Middelkerke,[12] but who resided in the suburbs of Liege. She had for several days been without news of her husband and children who had remained at home at Liege.

We then resolved to leave Middelkerke and return to Antwerp and Capellen.

THE DIGUE AT MIDDELKERKE

The cross denotes the Cogels Villa, now destroyed, where Dr. and Madame Beland stayed

We had left Middelkerke, “armes et bagages,” as we say in French. When I say arms and baggage it is a mere figure of speech, as our fowling-guns had been confiscated by the municipal authorities at Middelkerke and had been placed in the town hall. This precaution was taken in all communes of Belgium, to avoid untimely intervention of armed civilians, who, prompted by justified but unlawful indignation, might have committed acts which, under international rights, are contrary to the laws of war. An edict calling upon all citizens to surrender to the municipal authorities all kinds of arms in their possession had been posted and read everywhere, and, with rare exception, all Belgian citizens had strictly obeyed the decree. It may not be out of place to state here that[14] when the German authorities subsequently claimed that the Belgian Government was an accomplice of the civil population which, the Germans alleged, fired on German soldiers, they were only trying–but the effort was in vain–to find an excuse or justification for the inhuman acts they committed in Belgium.

On August 5 we left by train for Ostend on our way to Antwerp. A state of war then actually existed between Germany and Belgium. There were five people in the same compartment–three children, my wife and myself; one seat remained vacant.

The train was pulling out of the station when an excited individual, quite out of breath, rushed to our compartment, opened the door, but, before entering, turned and said–repeating the phrase several times in English–“Thank you,” to a person he left behind, at the same time waving his hand in farewell.

Entering the compartment, the newcomer took the vacant seat, and as I had[15] heard him speaking English, I asked him, “Are you English, sir?”

“No,” he replied, “I am an American.”

“Well,” I continued in English, “if you are an American we belong to the same continent; I am a Canadian.”

He did not appear to relish my overtures, but turned to admire the landscape from the window.

“May I inquire where you are going?” I ventured to ask after a short interval of silence.

“To Russia,” he answered.

“But why?” I said. “My dear man, you will never reach Russia; Germany is at war with Belgium, and I don’t see how you can get through to Russia.”

“Oh,” he said, “I shall go by way of Holland.”

His abruptness and reserve convinced me that he had no desire to continue the conversation. I began to entertain suspicions of the stranger, and my wife, who occupied the seat opposite to us, indicated by a significant glance that she, too, thought there was something extraordinary[16] in the demeanor of our travelling companion.

The train was running at express speed and a few minutes later we reached Bruges. On the station platform an expectant excited crowd had gathered.

The passenger I had addressed took up his suitcase and was hurriedly leaving the train when fifty voices in the crowd cried together: “C’est lui! C’est lui! C’est lui!” “It is he! It is he! It is he!”

On the platform the man was immediately taken in charge by four or five gendarmes, who asked him abruptly: “Are you German?”

He made no reply, but nodded his head affirmatively.

He was surrounded by the irate crowd and several individuals attempted to take him by force from the custody of the gendarmes, who, however, maintained their guardianship and protected the stranger against the threatened assault, though with great difficulty and at the risk of their own lives.

What happened to this man, or where[17] he was placed, I do not know. Was he the belated traveler he pretended to be, or was he actually a spy? I cannot say, but if he was a spy in the employ of Germany, and if he ever goes back to his country, one story he will be able to relate will describe the narrow escape he had at Bruges from the violence of a crowd of Belgians whose righteous indignation had been aroused by the insult to the nation’s honor and dignity by the great Central Empire.

It is unnecessary for me, I think, to insist here upon the patriotism displayed by the Belgian nation. All classes of the population, rich and poor, young and old, of all ages and of both sexes, were anxious to help the national cause of their country, threatened by the Germanic monster.

During the first days of August, 1914, on all sides I was asked the question: “Mr. Beland, what do you think England will do?” And I had from the outset a sincere conviction, which I expressed freely, that if Germany dared to execute her threat to violate the neutrality of Belgium Great Britain would declare war on the invader.

I recall most distinctly a demonstration which took place on the beach at Middelkerke, on the day Germany’s ultimatum was published. In the North Sea in the[19] offing the people could see what, to the naked eye, looked like a bank of clouds. Through the glasses, however, one could plainly perceive a squadron of British warships. When the news was announced the reassuring effect it had on the population was touching, and when I promptly called for three cheers for the British squadron the response was fervid and prolonged. From the moment it became known that Great Britain had signified to Germany that she would enter the fray to avenge the honor of Belgium and uphold the sanctity of treaties a tremendous confidence, an atmosphere of serenity, replaced the anxiety, depression and fear that had occupied the minds of all.

It was then that I went to Antwerp and offered my services as physician to the Belgian Medical Army Corps. I was given a cordial welcome and I took up my duty at St. Elizabeth Hospital, directed by Dr. Conrad, one of the most prominent and celebrated physicians of Antwerp, indeed of Belgium.

This hospital was in charge of Sisters[20] of Charity, whose name I now forget. Let it suffice to say that these noble women showed a devotion beyond human praise and reward. They were indeed martyrs to their cause.

It was toward the middle of August that the first wounded began to arrive at the hospital, coming from the centre of Belgium. All the physicians, except myself, were army physicians and had been enlisted at the outbreak of the hostilities.

It was on August 25, if I remember well, that the first German air raid was made on the City of Antwerp. It is difficult to convey an idea of the manner in which this event filled the citizens with terror. The Zeppelins were then unknown to the ordinary population. Twelve civilians–men, women and children–were killed by the bombs dropped by the raiders. On the following morning there appeared in La Metropole, an Antwerp newspaper, an article advising the burial of the victims at a certain place in the city, and the erection of a monument bearing the following inscription:[21] “Assassinated by the German barbarians on the 25th of August, 1914.”

The indignation of the public was great. The presence of German subjects in Antwerp had become impossible. Most of them, however, had by that time left the fortified portion of the city.

Every morning I used to bring with me to the hospital a copy of the London Times, and when we had a few moments of leisure the other physicians would gather around to hear the translation of the principal items of news.

Brussels was occupied by the Germans on August 18; Antwerp had now become the centre of the Belgians’ resistance; the seat of the Government and the general staff of the army had been transferred here.

In America one had not yet a full conception of the popularity of King Albert and of Queen Elizabeth among their subjects. Very few sovereigns enjoy to such a large extent the love and confidence of their people.

One day I had left the hospital and was[22] running toward the wharves on hearing that a detachment of German prisoners captured by the Belgians was to pass that way. I shall never forget the spectacle offered on that occasion by the entire population of the city crowding the main streets and avenues to get a glimpse of these German soldiers, invaders of the sacred soil of Belgium. And it was while wending my way through the streets to get a nearer glimpse of the captives that more than ever I realized how the Belgians resented the insult inflicted upon them by the barbarian hordes. The prisoners looked tired and haggard; they were covered with dust and mud; the sight was pitiable.

When returning to the hospital I encountered, half way down a narrow street leading to the Cathedral, a group of small boys who were making an ovation in honor of a young lady, neatly dressed, and accompanied by a small boy eight or ten years of age. The boys were joined by adults, who continued to cheer the Queen and the Prince as they passed through the[23] Place de Meir towards the royal palace. For it was the Queen and her son walking unostentatiously on the street. From every door and every window men, women and children continued cheering: “Vive la reine Elizabeth! Vive le petit Prince!”

In the last weeks of August and during the first three weeks of September, the Belgian troops concentrated in the fortified positions of Antwerp, and made several demonstrations against the Germans, who then occupied Brussels and Malines. At the hospital we were notified in advance of these sallies by the Belgian army, so that we might prepare ourselves to receive a fresh contingent of wounded the following day.

The wounded brought into St. Elizabeth Hospital were not, as a rule, very seriously injured, although at times and at first sight one would have believed them mortally injured. Happily, up to this date there had been no artillery attack on Antwerp. It is wounds resulting from artillery fire that are the most dangerous and the most frightful to look upon.

It is out of question for me to try to relate in full justice the military events which attended the attack and capture of Antwerp by the Germans.

Divers histories of the war, published in French and English since 1914, have reported the principal phases and details of the memorable event. I will confine myself then to certain incidents which I witnessed, and in which I participated.

Antwerp, as is well known, was reported to be impregnable. The city itself is surrounded by walls and canals. In addition there was a first chain of forts known as inner forts, and another chain of forts known as outer forts.

About September 26 or 27, 1914, it became apparent in Antwerp that the Germans were making a serious strategic demonstration[25] against the city on the side of Malines, situated half way between Antwerp and Brussels, and only five or six miles distant from the outer forts of Antwerp.

The military critics have often discussed the reasons which prompted the German high military command to undertake the conquest of the famous fortified position. It appears that what decided the Germans, more than anything else, to undertake the siege of Antwerp was the necessity to offset, in the minds of the German people, the painful impression created by the retreat of their army at the famous battle of the Marne. The Germans, you will remember, were forced to withdraw from both banks of the Marne between the 4th and the 12th of September, and a few days afterwards plans were made by the enemy to attack Antwerp.

Malines and a few villages on the south-west were first occupied, after which the attack was started against Antwerp through the outer forts on the south and south-east of the city.

The question was asked several times why did the Germans concentrate their first attack this way, when it would have been easier for them to capture the city by attacking from the west, whence they might have cut off any retreat of the Belgian army towards the North Sea. Between Thermonde and the frontier of Holland there is only a narrow border of territory which the Germans could have taken easily. It is still unanswered.

I have been assured that the Germans, after taking possession of a village named Hyst-Op-Den-Berg, had only to tear down the walls of a house to find, ready for use, a concrete base for a heavy and powerful piece of artillery.

Was this one of the numerous pre-war preparations of the Germans? No one can tell now, but it is a fact from this point the German artillery was able to bombard the forts of Waehlen, Wavre, Ste. Catherine and Lierre, which were the first ones destroyed.

At that time a large number of wounded soldiers were being brought to the hospital[27] every day. Every time a new batch of wounded was brought in the doctors would, after rendering first aid, gather round in order to obtain some details of the progress of the battle. The reports became more and more alarming. The Germans were making their way steadily toward us. It was next reported that enemy detachments had crossed the Nete river; that in a short while the artillery would be able to bombard the city itself.

I remember particularly a lieutenant of artillery who was under my care at the hospital. He described to me the scenes which took place during the bombardment of the fort he occupied. He told me that although accustomed to the tremendous detonation of the guns, he could not find words to adequately express the effect of an explosion caused by the firing of a shell from a 28-centimetre howitzer or a 42-centimetre gun.

I think it was on Saturday, October 3, that the news spread like lightning that Mr. Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty of Great Britain, had arrived[28] in Antwerp. A few hours later we were told at the hospital that the English statesman had gone back, after assuring the Belgian authorities that help would be forthcoming immediately. As a matter of fact, on the days immediately following, British Jack Tars arrived in Antwerp. They crossed the city from l’Escaut to the forts on the south-west amid the indescribable enthusiasm of the population, and took position in the Belgian trenches.

The confidence of the people in the besieged fortress, which had become somewhat shaken, was at once restored and rose higher than ever. And I desire here to express my admiration for the conduct of the British naval squadrons, which was beyond praise. Their behavior and courage were alike unequalled, and whatever criticism may have been advanced in the British press at that time of sending these naval forces into Belgium, it is my sincere belief that these troops played an exceedingly important part. While they did not prevent the fall of Antwerp, they succeeded, at all events, in holding back the[29] German advance for a time, and covered the Belgian army’s retreat, first through the city, thence to the other side of the Escaut, in the country of Vaes, toward St. Nocalos, Ghent, and Ostend. The British marines were the last to leave Antwerp. During the night of October 8-9 a small number of them fell as prisoners into the hands of the enemy; others evaded the Germans by crossing into Holland; the remainder followed in the wake of the Belgian army.

Antwerp itself was bombarded for thirty hours unceasingly. The bombardment started in the evening of Wednesday, October 7, and continued until the following Friday morning. During this time it was estimated that no fewer than 25,000 shells fell into the city, shaking it to its deepest foundations.

We remained at the hospital until the following day, Thursday. We had removed the majority of our patients to Ostend. Only a few remained under the care of the brave nuns. I myself was preparing to leave, when a shell burst right in the[30] centre of the operating room close upon the ward where I was occupied. I was slightly wounded, and I left the hospital a few minutes later.

This was on Thursday, October 8, and as I rode on my bicycle through the now deserted streets I could hear above my head the whizzing of the shells fired by the enemy in the direction of the Belgian army headquarters.

The Belgian army headquarters were then at the Hotel St. Antoine, on the Marche aux Souliers (shoe market), a small thoroughfare which leads from Place de Meir to Place Verte. On the day following the fall of the city, I rode back to Antwerp on my bicycle, and to my great surprise I saw that while every vestige of buildings on the opposite side of the street had disappeared–blown into atoms by the German shells–the Hotel St. Antoine had not been touched. The shells had merely grazed the roof of the building before crashing down the opposite side of the street.

The night of October 8-9 was terrible[31] and sinister. From the roof of the house we lived in, at Capellen, we observed the city being devoured by the flames. From the spot where we witnessed this awful scene, it looked as though the whole city were on fire. The oil reservoirs were burning at the same time that other parts of the city were being consumed by the devastating element. In the midst of this horrible carnage, we could see the tower of the great, magnificent cathedral pointing, like the finger of God, toward heaven. It was visible for a minute, then invisible–swallowed up in enormous tongues of fire. In the distance toward the south, where total darkness prevailed, we could observe from time to time flashes of the explosions caused by the German artillery vomiting its volleys of shells on the burning city.

It was an appalling spectacle which lasted through the night. The formidable vibrations caused by explosions repeated on an average of 300 per minute was an experience which is still painful for the imagination to dwell upon. Then on the[32] morning of Friday, October 9, a dismal silence followed the carnage on the fortified city. Antwerp as a Belgian fortress was no more!

What a touching spectacle–that of a whole people fleeing to another country! This sight we witnessed in all its tragic pathos. While the Germans approached from the east and south-east towards Antwerp, the population of Malines and the neighboring villages, the people of the villages situated between the outer and the inner lines of the forts, the inhabitants of Duffel, Lierre, Contich, Viedieux and fifty other villages had poured into Antwerp, and when it became evident, on Tuesday and Wednesday, the city would be subjected to the bombardment of the German artillery, all these brave people, probably 300,000 in number–men, women, and children–who had sought refuge in Antwerp, where they hoped they would be safe from the onslaught of the Huns, scattered in all[34] directions to escape the threatening fire. Some 200,000 people, perhaps, crossed the Escaut river and fled, some in the direction of Holland, others toward Ostend. Between 250,000 and 300,000 traversed the highway which leads from Antwerp to Holland.

During the last days of the agony of Antwerp, I was the witness of the constant departure of this desolate people towards Holland.

I had to journey each morning on my bicycle from Capellen to Antwerp and return in the evening. In the morning I had to ride against the surge of escaping refugees; in the evening I rode with the tide, as it were. How can I describe the pathetic sights I witnessed during these days of horror? I saw men and women–many far advanced in years; some of them carried young children on their backs, some in their arms; others pushed carts and wheelbarrows and small vehicles of all kinds, which contained these people’s whole belongings, remnants of the wreck of their homes; beds and bedding, furniture[35] and clothing, religious books and articles of piety. In this great moving caravan were cows and goats, horses and sheep, and the ever-faithful dog–all being led away by the refugees–truly a shattered cohort wending its way with bowed heads, drawn faces, weary eyes, haggard and livid. I say it was a terrible, heartrending sight to witness, one that I hope God will prevent me from ever seeing again.

I shall never forget one case, more pitiful, perhaps, than all the others. It was that of an old man who was pushing a wheelbarrow in which sat his old wife, crippled and paralyzed. It was night, about 9 o’clock. We invited the old couple to spend the night in our home.

During the last week of Antwerp’s resistance, hundreds of refugees would enter the enclosure of our home at Capellen and there improvise for themselves a refuge for the night in the bushes or under the trees. Others, the older men, the women folk and the children, were lodged in the building. Rooms, corridors, garrets, and even the cellars were filled to capacity.

On the following morning these poor refugees would start again on their distressing journey towards Holland–the long, sad walk of a whole people leaving behind them their beloved country, their souls tortured by grief and anguish.

On Friday, the day Antwerp fell, the German troops entered the city at about 9 o’clock in the morning, and what I relate now was conveyed to me personally by a German officer, who took part in the attack on Antwerp and was billeted in our house for more than three months after the capture of the city.

When the Belgian military resistance ended–that is, during the night of the 8th to the 9th of October–the Germans, as I have already stated, continued to bombard the city, but in the morning at 7 o’clock the artillery’s action ceased. Two hours later the order was given to a regiment to pass inside the walls of the city. The Germans thought they would have to fight foot by foot within the walls. For some reason, the opinion prevailed that the whole Belgian army–between 90,000 and 150,000 in[37] number–had concentrated for a last stand within the walls of the city itself.

The Germans, who, according to the information given to me by the officer I have mentioned, had only 55,000 men, actually feared to meet the Belgian army in close battle. But the order was given to enter, and regiment after regiment, with fixed bayonet, marched into the city, alert but quietly, as though in constant dread of being surrounded.

The city was virtually empty. No civilians or military were to be found. The German troops were ordered to halt in front of the Athenée, and a group of officers were directed towards the Belgian army headquarters, in order to obtain information. They were met by one lone janitor, who heroically refused to state where the Belgian army had gone.

The deputation of officers next crossed to the City Hall, where the principal municipal officials awaited them. Here also information as to the direction the Belgian army had taken was refused.

A demand was then made by the German[38] officers for the surrender of the city, but the municipal authorities replied: “As the city is under the command of the military authorities, we have not the necessary authority to surrender it.”

And that is why on the following day a German officer staying at Capellen told us that the situation at Antwerp was rather precarious. While the Germans occupied the ground, the city had not surrendered!

Antwerp had only fallen. The Belgian army had withdrawn towards Ostend. It had traversed the coast road to Nieuport, where the troops took up their position. We all know now what an important and heroic part they played behind the locks of Nieuport. But the whole Province of Antwerp had fallen under heel of the Hun!

Friday, October 9, 1914, was a day of anxiety and fear for the city of Antwerp and the villages situated inside the fortified position. The Germans were within our midst, and from 9 o’clock in the morning the soldiers of the Kaiser began to extend their positions around the fortress, along the routes from the east and south-east. What was to become of Capellen? was a question asked by all of us.

All along the paths of the park of Starrenhof (residence of Mrs. Beland-Cogels), on the Antwerp-Holland highway in front of the Town Hall, groups of people who were left gathered to discuss the situation. Each asked the other: “When will the Germans reach here?” And fear was deeply lined on all faces, for the reports had reached us from the villages in the centre[40] and in the east of Belgium which were far from reassuring as to the probable conduct of the German soldiery.

Refugees from the village of Aerschot, who were lodging at the farm of the chateau, drew a startling word picture of the tragic events which occurred at that place. Murder and arson had held sway for several days. In brief, the whole population of Capellen, including the refugees, were in a state of great nervousness.

Night fell on the city and the surrounding country without the Germans having put in an appearance. At about 9 o’clock, while our family with their friends were talking together, a fearful explosion was heard. What had happened? Each of us had different ideas, but the most plausible explanation was that a Zeppelin, flying over the village, had dropped a bomb into the yard of the chateau. Then the true explanation burst upon us suddenly. The fort nearest to the chateau was that of Erbrand, distant about one kilometre from us. The commanding officer of the garrison had ordered the fort blown up previous[41] to its evacuation. The shock was so tremendous that an oil lamp burning in the hall where we sat was extinguished, and several windows were shattered. The bombardment of the city had broken electric light wires and the gas conduits were wrecked, so that oil lamps and candles were our only means of obtaining light.

Naturally, the explosion did not tend to soothe our nerves, and the entire family remained together in a large hall for the rest of the night. Beds were improvised and each of us obtained what rest was possible in the exciting condition of the time, which was very little.

About 1 o’clock in the morning a servant girl knocked at the door and told me that a man wished to see me. It was a Belgian, who urged me to at once leave with the family for Holland. He informed me that the Germans had left Antwerp a few hours previously, and were fast approaching Capellen; that they had already reached the village of Eccheren. They were pillaging and burning everything on the way. The[42] man added that he himself was on his way to Holland with his aged mother.

“Where do you come from?” I asked him.

“From Contich,” he replied.

“Where is your mother?”

“I left her in a farmer’s house nearby,” he said. “I will go back to get her presently and take her to safety.”

“It is well,” I told him, “and I thank you for the warning you have given me.”

When leaving the house he urged again: “You have not a moment to lose. The lives of your wife and children are in danger,” he persisted.

After his departure I ordered a servant to awake everybody in the building–our immediate family and relatives from several places who had been lodging with us since the bombardment started. We held a family council–a real war council, if ever there was one. All were inclined to follow the man’s advice and start off for Holland. The dear old parish priest of Schouten, a distant relative of the family, wished us to leave at once.

I suggested that my wife and the children should go, taking with them all the baggage they could carry, while I would remain with Nys, an old and faithful servant who had been with the family for over thirty years. The old servant was quite willing to stay, but, as one might suppose, my wife objected to this arrangement. “We shall all remain together, or we shall all leave together,” she said.

Thereupon I proposed that we should take counsel of an old resident of Capellen, Mr. Spaet, a man of wisdom and experience, of German origin, but who had lived long in the country and could claim Belgian citizenship for upwards of forty years. He had two sons in the Belgian army. This proposal was accepted unanimously.

I accordingly left to see Mr. Spaet, wending my way through the line of fugitives who were still crowding the highway at this early hour of the morning.

Mr. Spaet was at home. In reply to my questions, he said he had no advice to give me, but insofar as he himself was concerned[44] he intended to go back to bed as soon as I left him. I returned to the chateau somewhat reassured, and, addressing the members of the family and our friends, who had in the meantime made preparations to leave for Holland, I said: “Every one goes back to bed.” I related my conversation with Mr. Spaet, and then we all returned to bed, but, I am sure, none of us to sleep.

Subsequently another fearful explosion shook the house. It was the second fort–that of Capellen–which had been blown up. The large building in which we lived shook to its foundations.

A few minutes afterwards the same servant who previously knocked at the door of the hall came up again. She stated that our previous visitor had returned and demanded to see me. I went to him a second time. He repeated his monition, told me not to postpone the carrying out of his previous advice, but to act upon it immediately.

My suspicions were aroused by his manner and persistence, so I said to him:[45] “What about the other residents of Capellen?”

“They have all gone,” he replied.

“And Mr. Spaet?” I asked him.

“Mr. Spaet is now in Holland with the others,” he said, without a tremor.

I knew that the man was lying, and if he was capable of lying he would be capable of stealing. He was one of those human jackals whose sinister plan it was to precede and follow the armies and plunder the houses as soon as the occupants had left them. I turned to the man and said: “Now, you, sir, take counsel of your own advice to me, and leave at once.” He went. But what a night was that one …!

At daybreak a radiant sun gilded the autumn foliage. As I opened a window I saw that the women and children who had sought refuge in the park of the chateau were still sleeping. The Germans had not yet arrived. They were not very far away, however.

On the morning of October 10, at about 9 o’clock, a messenger called at our house and, on behalf of a group of citizens, invited me to the City Hall. I was at a loss to know why my presence was wanted there, and decided to go at once. The City Hall was no more than one kilometre distant, and on my way I had to cross the unending procession of refugees slowly wending their toilsome way in the direction of Holland.

At the City Hall, I was met by a number of representative citizens of Capellen. They asked me to join them in receiving the German officers, who were then due to arrive at any moment. I could realize how hatred was accumulating in the German heart against Great Britain, for was Britain not the prime cause of their present[47] check–the actual obstacle of the military promenade which the Germans had for forty years dreamed of making from the German frontier to Paris? The initial plan of the German high command had been frustrated, and for this disastrous failure they would hold that the English were naturally and justly responsible. I, therefore, suggested to my fellow-citizens that in my quality as a British subject I was more likely to be a hindrance than a help to them. They insisted, however–and with some plausibility perhaps–that the German officers would not know to which nationality I belonged, and that it was of immediate importance to make as good a showing as possible in numbers–there were not more than five of us all told, the others having crossed the frontier into Holland. Under the circumstances, I accepted their proposal and agreed to stay with them and meet the incoming Germans.

At 10 o’clock an individual burst into the room in which we were assembled and[48] made the simple announcement: “Gentlemen, a German officer is here.”

Before the fall of Antwerp I had a close inspection of a number of German prisoners of war as they marched in file and under Belgian escort along the streets of the city, but I had never yet seen either near, or at a distance, a real Prussian officer, and I must confess that my curiosity was greatly aroused by the announcement of the imminent arrival. Ere we had time to advance to meet him, there he stood in the doorway, dressed in the uniform of a captain of German artillery and wearing the pointed helmet. He gave us the military salute, turned to Mr. Spaet and, speaking in German, said that in civilian life he was a lawyer and practised his profession at Dortmund. He looked at each and every one of us several times as though searching our souls to discover what were our inmost feelings and sentiments. He was manifestly surprised by the fact that Mr. Spaet, a Belgian, could speak such perfect German, and inquired of him how he had acquired his knowledge of his own[49] language. Mr. Spaet replied frankly and honestly and then asked:

“What must we do?”

“Nothing,” replied the German officer. “However, you will not have to deal with me; I am only a scout. It is with Major X—, who will be here shortly, that you will have to make arrangements.”

With these words he took his leave, and a few minutes afterwards an automobile, containing the real negotiator, a Prussian major, who was accompanied by a very elegant officer, stopped in front of the Town Hall. This major typified the Prussian officer my imagination had pictured. Resplendent in uniform and glittering helmet, with blonde moustache trained a la Kaiser, he stood erect as a letter I, and stiff as an iron rod.

At the time there was, as in preceding days, a large crowd in the public square fronting the Town Hall. It was the direct route from Antwerp to Holland, and there were now accumulated here refugees from the four corners of the fortified position. Seemingly annoyed by such a gathering,[50] the Prussian major demanded an explanation, which Mr. Spaet gave without hesitation.

“Whither are these people going?” he inquired.

“To Holland,” Mr. Spaet told him.

“Why?”

“Because they seek refuge from German fire,” answered Mr. Spaet.

“But since Antwerp has fallen, there is no further danger,” stated the major. “Tell these people to return to their homes. They will not be molested.”

Naturally we feared many requisitions would be made upon us.

The major informed us that only horses would be taken. “We must have horses,” he added.

But it was explained the only horses in Capellen belonged to the farmers, and these animals were absolutely needed if the crops were to be garnered.

“Well,” said the major finally, after further explanations,[51] “only one infantry company will be sent to Capellen, and you must see that the officers are well treated. As to the soldiers, well, you may billet them anywhere you like–in the schoolhouse, for example.”

The German officer demanded to know in what condition were the forts around Capellen. We told him our present impression was that they had all been destroyed by the garrisons immediately before their evacuation. He took two of our party with him in his automobile and made a tour of the forts of Capellen, Erbrand, and Stabrock. He brought us back to the Town Hall and then departed. I never saw him again.

In the afternoon of Saturday, October 10, a company of infantrymen arrived in front of the Town Hall. At the word of command, two soldiers left the ranks and entered the building. A few minutes afterwards the crowd witnessed the humiliating and supremely painful ceremony of the lowering of the Belgian flag, which had flown from that flag-staff for nearly one hundred years, and in its place was hoisted the German standard. Capellen then was definitely subjected to enemy occupation.[52] As Capellen is situated at the extreme north of the fortified position of Antwerp, consequently the German flag floated as the breeze blew from the frontier of France to the frontier of Holland.

And mourning entered every home.

“Do please hurry, and return to the house, my dear sir and madame, for the Germans are there.”

It was a young lady who thus addressed us on the sidewalk midway between the church and the chateau. My wife and I were returning from church when we were thus apprised that the Hun was more than at the gate–that in fact he was beyond it, and actually in the house awaiting our return. We hastened our footsteps homeward. The first thing we observed was an automobile standing opposite the main entrance.

In the house we found ourselves in the presence of a German officer of medium build. He bowed very low to my wife and myself, and then explained that the automobile standing at the door in charge of[54] three soldiers belonged to him. He spoke the French language and demanded lodgings.

Such an unexpected request was perplexing, to say the least. We could hardly refuse it, although, candidly, we did not relish the proposition in the least. I explained that the house was full of refugees, who were our relatives; that they had been with us for over a week, and that under the circumstances it would be difficult, if not quite impossible, to find fitting accommodation for him. He insisted, however, saying the three soldiers who accompanied him–a chauffeur, an orderly and a valet–could sleep in the garage, and he alone would require a room in our house. I thought that in stating my nationality he might change his mind; so I said to him: “I am very anxious to return with my wife to Canada, for I am a Canadian, consequently a British subject.”

“I know that,” he replied. “I know that.”

I have to confess that I was astonished to learn that he knew my nationality. What[55] a marvelous service of espionage these Germans had!

“Yes,” he added. “I can say definitely that you must not leave Belgium. There is nothing to prevent you remaining here, even if you are a British subject. I have also learned that you are a physician, and that as such you served in hospital at Antwerp. You need have no fear, then, in remaining here; you are protected under laws of military authority.”

I exchanged a glance with my wife and together we reached the same conclusion. We would receive this officer in the house, find accommodation for his servants, and, for ourselves, we would remain in Capellen. As a matter of fact, we were very happy to be able to reach this decision, as Capellen, at that time, had no other medical doctor. Several of the local physicians had joined the army, and others had gone to Holland. I might, therefore, be able to render some service by remaining. My wife was at the head of a charity organization long established at Capellen, and which, in consequence of the war, had become[56] of exceptional utility and importance. This was how we came to remain, and the children with us.

The German officer came from Brunswick. Goering was his name. For two years he had been attached to the German Embassy in Spain, and later he was for eight years at the German legation in Brazil. He had, it must be acknowledged, acquired a great deal of polish through his international experience. He spoke English and French fairly well. He had none of the haughtiness and self-conceited characteristics of the ordinary Prussian officers. But he entertained no doubt about the ultimate success of the German arms, above all at that moment when the world-famed fortress of Antwerp had just fallen into their hands. He professed to believe that German troops would land in England within a few weeks, and this opinion was shared by his three military servants. The Germans were already in Ostend, and from that place an expeditionary force was to be directed against England. That project was on every one’s lips.

POOR BOYS IN CAPELLEN BEING FED BY THE ST. VINCENT DE PAUL

The arrow and the cross designate Madame and Miss Beland

This officer remained with us for about three months, leaving at the end of December. I must acknowledge again that I never found in him the typical Prussian officer. This is easy to conceive when one recalls that for ten years immediately preceding he had lived in foreign countries, and associated with diplomats and attachés of embassies and legations of many countries. Naturally, he believed in the superiority of the German race. He boasted of German culture. He was convinced German industry was destined to monopolize the world’s markets. He insisted that France was degenerate, that Britain had not, and would never have, a powerful army, and said Dunkirk and Calais would surely be captured within a few weeks, etc., etc., etc.

During October and November of that year it was possible, although the frontier was guarded by German sentries, to cross into Holland on any pretext whatsoever. One might go there to buy provisions so long as the sentries were satisfied the party intended to return. It was only at Christmas,[58] 1914, that the frontier between Antwerp and Holland was “hermetically closed”–if I may use this term. At the distance of about one kilometre from the frontier, a post of inspection and control was established. Here on Christmas Day the most absolute control of passports was ordered. No one could cross unless provided with a permit issued by the German administration in Antwerp. We were, therefore, at that time cut off from all communication with the outside world.

Winter had come; distress was great in Belgium, and but for the foodstuffs and clothing forwarded from the United States and Canada–but for the charitably disposed rich families, who can tell what horrors the population of the occupied territory would have gone through.

Towards the end of October, 1914, two or three weeks after the evacuation of the fortress of Antwerp, His Eminence Cardinal Mercier issued a pastoral letter to his clergy and people entreating the Belgians who took refuge in Holland during the terrible weeks of the bombardment of the northern region of Belgium to return to their homes.

This letter contained a special provision which is remembered to this day. The Cardinal stated that, after a conference with the German authorities, he was convinced the inhabitants of the Province of Antwerp would be exempt from all annoyances and would not be molested for any personal delinquency.

“The German authorities,” the Cardinal added,[60] “affirm that in the event of any offence being committed against the occupying authority this authority will seek out the guilty party, but if the culprits be not found, the civil population need have no fears, as they would be spared.”

This was quite clear. The episcopal document was, of course, published in Holland and, consequently, many thousands of refugees returned to their homes in Belgium.

About the 15th of December of the same year–that is to say, about two months after the Cardinal’s letter appeared–two Capellen lads, 14 or 15 years of age, boarded a locomotive standing at the station, where it had been left by the engineer and fireman while they went to dinner. The boys amused themselves with the lever and soon had the engine running backwards and forwards alongside the station platform. Here they were caught by German soldiers who carried them off to Antwerp, where they were summarily tried, and sentenced to serve three weeks in jail.

The incident was considered closed; but not so, as we shall see. On the following day, Major Schulze, if I am not mistaken,[61] the commanding officer at Capellen, requested the burgomaster to supply him with a list of twenty-four citizens, including the parish priest, the Rev. Father Vandenhout, and a former burgomaster, Mr. Geelhand. These twenty-four citizens, it was ordered, would be divided into groups of eight men each, and each group would, in turn, keep guard on the railroad every night from 6 o’clock until 7 o’clock the following morning, and this until further orders. This raised a hue and cry in the village. The citizens asserted, with reason, that the boys guilty of interfering with a locomotive had been caught; that the offence was not serious–was, in fact, nothing at all but the pranks of two boys. Everybody now recalled Cardinal Mercier’s letter, and the assurance upon which it was based, as given by the German authorities, namely, that no personal delinquency would be followed by reprisals against the civil population. What was to be done? Counsel was taken on all sides. The principal citizens met secretly and decided[62] to submit the case to the Governor of Antwerp, General Von Huene.

But it was of no avail; the twenty-four citizens whose names appeared on the list were compelled to keep guard in front of the station during the cold, wet nights of December and January. On Christmas eve, the group to which the old priest, Father Vandenhout, belonged was on guard. This priest, about 70 years of age, and seven companions paced to and fro in front of the station, throughout a cold and stormy night. It was not until the 15th of January that an order from Antwerp ended this arbitrary ruling of the local military authorities.

It was at about that time that a new officer appeared at the chateau with a request that we should receive him in the house. This man was much less pleasant in manner than his predecessor. He had not lived in Spain or in Brazil. He had come straight from Eastern Prussia. He was violent and arrogant. He treated his orderly with extreme severity. The house trembled each time he started to scold the[63] man, and this happened frequently enough. The officer left after a stay of three weeks, and God knows we never regretted his departure.

Once again we were free from the Germans’ presence. True, we could hear their heels tramping on the road outside, but under the domestic roof the family lived quietly in peace.

One of the Capellen physicians having returned from Holland, my wife and I decided, after consulting the children, to take steps to leave the occupied country, with the intention of crossing later to Canada.

Early in February, 1915, my wife and I went to Antwerp, and called at the Central Office for the issuing of safe-conducts (passports). We submitted to the two officers in charge our request to be authorized to leave Belgium.

“Where do you wish to go?” inquired one of the officers.

“To Holland,” I replied.

“For what purpose?”

“In order to embark for America.”

“Why go to America?”

“Because I wish to return home to Canada, where I reside.”

“Then you are British subjects?”

“Yes.”

The officer appeared surprised. He turned to his comrade, and then looked at us, my wife and I, from head to foot.

“You are British subjects?” he repeated.

“You are right.”

“How long have you been in Belgium?”

“I came to Belgium before your arrival–that is to say, in July,” I replied.

“What are you doing here?” he inquired.

A colloquy between the two officers and ourselves followed for a few minutes, during which it was easily explained that my presence in Belgium had nothing mysterious about it, even from a German viewpoint.

Apparently convinced that he was not in the presence of a spy employed by the British Government, the first officer confessed that he could see no serious objection to the issue of a permit for our leaving Belgium, but he said that insofar as British subjects were concerned explicit instructions had been given, and he could not then give us the passport we requested without being first authorized to do so by the chief of the military police, Major Von Wilm. He advised us to see the major,[66] and we proceeded to carry out the advice. On our way to the major’s office I remarked to my wife that it was quite possible I might never come out of this office, once inside. We went on, however. Major Von Wilm received us courteously, and listened attentively to our story.

He, too, was convinced, apparently, at least, that I was not a spy. He did not anticipate any obstacle to the issuing of a passport, but he said he would have to talk the matter over first with the governor of the fortress. He advised us to return to Capellen and await instructions.

A few days afterwards we received a letter from the major. It read as follows:

Antwerp, Feb. 8, 1915.

Mr. and Mrs. Beland,

Starenhof,

Capellen.

Sir and Madam:–

Regarding our conversation of a few days ago, I have the honor to inform you that a safe-conduct will be granted to you on two conditions. The first is that Mr.[67] Beland will formally undertake never to bear arms against Germany during the continuance of the war, and second, that all properties belonging to you in the occupied territory of Belgium shall be subjected, after your departure, to a tenfold taxation.

(Signed) Von Wilm.

It then remained for us to decide what to do. I deemed it advisable to return to Antwerp and discuss at greater length with Major Von Wilm, particularly the question of the tenfold taxation. After a prolonged conversation with him, and after receiving renewed assurances that I might remain in the occupied territory without fear of annoyance, molestation, or imprisonment on account of my profession and medical services I was rendering the population, we decided to remain without further protest until the month of April. By this time the taxes would be paid. In the meantime this high German official, who conducted important functions in the Province of Antwerp, pledged himself to discuss with the German financial authorities[68] at Brussels the question whether the onerous conditions of a tenfold taxation upon all the properties we owned in Belgium might not be removed. The ordinary taxes were duly paid in April, and I again visited the major at Antwerp, urging him to enter into negotiations with the German financial authorities on the question already alluded to.

Once more he promised to take the matter into consideration as soon as his occupations would allow him; once more he assured me of proper protection, and told me I might continue in perfect security. There could be no question at all of my being interned, he said, and as to the question of taxes, he had no doubt whatever that the matter would be settled to my entire satisfaction.

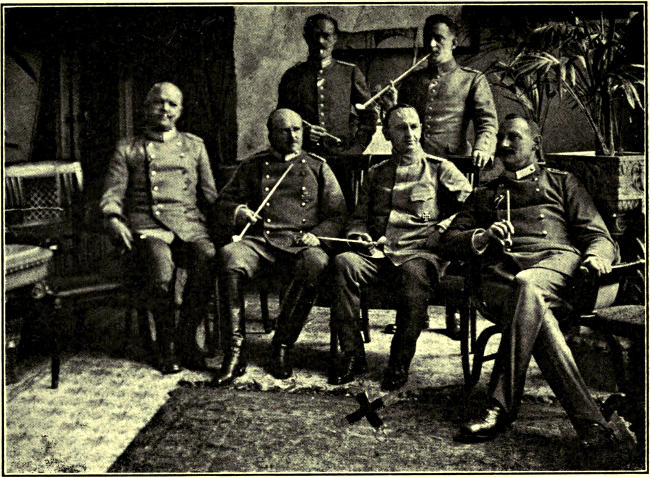

GROUP OF GERMAN OFFICERS AT ANTWERP

Cross indicates Von Wilm who was instrumental in the arrest and internment of Dr. Beland

Military police inspection at this period became much more stringent. If one were walking along the street, or visiting a neighbor, or making a sick call, he was liable to be kept under the closest surveillance. It was not an uncommon experience in the course of a walk in the garden to suddenly perceive the ferret-like eye of an official watching you from a cluster of foliage nearby. As a matter of fact, we felt our every movement was spied upon. The least infraction of the regulations imposed by the occupying authority–and God knows the number of these regulations; they were posted everywhere–I say the least infraction was punished by a money fine or with a jail sentence.

It was a few days after the sinking of the Lusitania. All British hearts felt a[70] new bitterness. At the same time a greater feeling of arrogance was reflected from the German mind. The Boches had unbridled their terrorism on the seas, and they now would attempt to make their conduct more appalling in occupied territory.

All of this stimulated our desire to leave Belgium to return to Canada.

On May 15, at 8 o’clock in the morning, I was apprised by a messenger that my presence was wanted at the Town Hall. It was not without a feeling of some apprehension that I made my way towards that building. In the office of the Mayor where I was introduced, I saw the Mayor and a non-commissioned officer. The Mayor, who was one of my friends, said, with a significant glance towards me: “This gentleman wishes to speak to you.”

“What is the matter?” I asked.

“You must go to Antwerp,” replied the non-commissioned officer.

“Very well,” I said, “I will go immediately on my bicycle.”

“No,” said the non-commissioned officer,[71] “you had better leave your bicycle here at the Town Hall. I wish you to accompany me.”

A few minutes later we arrived at the station which was transformed, like all the other stations in the occupied country, into a military post. The non-commissioned officer directed me to a waiting room where there were a group of several soldiers chatting and smoking.

One of these soldiers at a word of command came forward, put on his pointed helmet, slung his rifle over his shoulder, and simply said: “Commen sie mit.” I was right in interpreting his remark to mean “Come with me.” For the first time in my life I had the honor (?) of parading along the street in the company of a disciple of Bismarck!

The people of Capellen, who knew me very well by this time, hurried to the doors to see me pass. A few minutes afterwards we arrived in Antwerp. I was conducted to the Bourse, a large building, which had been struck and damaged by a bomb during the air raid of August 25.

The Germans had established in the[72] Bourse an office for the “control of foreigners.” I did not know of this as yet, but it was not long before I was made aware of it. I was taken into a large room on the door of which I had noticed the name of the officer in charge. He was Lieut. Arnins. I ask the reader to remember this name. I shall never forget it, nor the personage himself.

In the office was a long table with a soldier at each end; an officer, small of stature, and with a puny face, and a non-commissioned officer, bigger in build than his companion. The officer addressed me, speaking with undue violence: “Sir,” said he, “you would have avoided the annoyance of being brought here, under military escort, if you had reported yourself, as it was your duty to do.”

“I was not aware that I had to report,” I replied.

“That’s false,” asserted the officer in a voice louder than before.[73] “That’s false. I have had posted in all the municipalities of the Province of Antwerp a notice enjoining the subjects of countries at war with Germany to report themselves before a given date. You could not ignore this.”

“Most assuredly I was not aware of it,” I said. “Will you please tell me where, in Capellen, you had this notice posted?”

“At the Town Hall,” the officer answered.

“Well,” I continued, “I reside at about one kilometre distant from the Town Hall, and I have no occasion to go there.”

“It is useless for you to attempt to explain,” he declared. “You have knowingly and wilfully avoided military supervision, and take notice that this is a very serious offence.”

“Sir,” I replied, “when you affirm that I have avoided military supervision, you are placing yourself in contradiction with the facts. What you say does not conform with the truth.”

The officer jumped to his feet as if moved by a spring.

“What is that you say?” he demanded.

“Simply that I never had any intention to disobey the regulations you have posted up,” I answered calmly.

“You take it in a rather haughty manner,” he said. “Do you think we are not aware that you are a British subject?”

“I never thought so,” I replied.

“You are a British subject, are you not–you are a British subject?”

“You are quite right–I am a British subject.”

“It is well for you that you do not deny it.”

“Reverting to the accusation you have made against me,” I said, “let me ask you a simple question: If it is established that the chief of the German military police here, in Antwerp, knows me personally; if he and I have talked together at length; if he knows my nationality and under what circumstances I am in Belgium; why I came here; what I am doing, and what I hope to do, will you be of the opinion still that I have infringed the regulations knowingly and wilfully in not reporting to this office?”

The German officer was visibly abashed. He went to the telephone and spoke with the chief of police. He became convinced[75] that what I had said was true, and while not so violent as hitherto, he said, in a haughty manner: “Well, you ought to know that in the quality of stranger you are not allowed to go around without a card of identification. We will give you your card and you must report yourself here every two weeks.”

The officer had to give full vent to his wrath on somebody, so, turning to the soldier who had remained near me, he said, brutally, “Los!” (Go!)

The soldier, poor slave, turned on his heels, struck his thighs with his hands, looked fixedly at his superior officer, and walked hurriedly from the room.

An hour later, and feeling really not too much annoyed by my trip, I returned to Capellen, where I was surrounded by my family and a group of friends all anxious to know in every detail what happened to me on my visit to Antwerp.

Apparently I was safe. With my card I might go freely among my patients. At the end of two weeks’ time I reported myself[76] in Antwerp, where my passport was examined and found to be correct.

I still was allowed to breathe, with all my lungs, the air of freedom!

One can readily realize that a journey to Antwerp under the escort of a German soldier had rather humiliated me. I wrote a letter of protest to Major Von Wilm, relating all the incidents of the day.

A few days afterwards I received a reply from this officer, who explained that my arrest was owing to a denunciation; that he had supplied the German military police with all necessary information; that everything was now properly arranged, and that I need have no inquietude as to the future.

I succeeded in taking with me to the prison later this letter written by Major Von Wilm, and I also was able to smuggle it out of Germany on my release. The reader will find the letter reproduced elsewhere in this story. It is a document[78] which I consider of the greatest importance. In it the chief of the German military police in Antwerp is on record as declaring over his signature that I need not be uneasy as to the future, as I should be allowed to enjoy immunity.

This immunity, however, was to be of short duration. On June 2, when I believed I had been freed from all annoyance, two soldiers presented themselves at the house and requested me to accompany them to Antwerp. I felt convinced that surely this time it was to be a simple visit to an office of some kind, but unaccompanied by inconvenience or vexation.

I left the house without hesitation, taking with me only my walking cane. One of the soldiers spoke French. He appeared to think my call to Antwerp was a mere formality, and that I might be allowed to return to Capellen the same evening.

Arriving in Antwerp, the soldiers conducted me to a hall situated near the kommandantur on des Recollets street. In this hall I saw a large number of people whose appearance was not very reassuring.[79] There were men and women who, judging by appearance, were all more or less bad characters.

Left alone by the two soldiers I made a close observation of this doubtful-looking crowd, and the non-commissioned officer who was in charge of them. I tried in vain to recall the place where I was, and so decided to secure the information from the non-commissioned officer. “Well,” said I to him. “What place is this? What am I brought here for? What do they wish to get from me? Do you know?” The non-commissioned officer did not answer. He just shrugged his shoulders as though he did not understand what I said. I thereupon gave him my card, together with a message for the major. A few minutes later an officer appeared and requested me to follow him. It turned out to be Major Von Wilm’s office into which I was now introduced.

“Mr. Beland,” he said, “I am desolate. New instructions have just arrived from Berlin and I must intern you.”

I had not time to express surprise or[80] utter a word of protest before he added: “But you will be a prisoner of honor. You will lodge here in Antwerp at the Grand Hotel, and you will be well treated.”

“But this,” I said, “does not suit me. First of all, my wife and family are not aware of what is happening to me. In any event I must go back and inform them of my predicament and obtain the clothing I shall need at this hotel.”

Visibly embarrassed through being unable to grant my request even for one hour the major was unable to reply at once. He pondered, walked a few paces in front of his desk, then what was Prussian in the man asserted itself and he said: “No, sir, I cannot permit you to return to Capellen. You may write to madame; tell her what has happened, and I will forward the letter by messenger.” This was done.

The major made every effort to convince me that my detention would be of short duration; that all that was required was evidently to establish my quality as a practising physician; that as soon as documentary proof of this could be placed in the hands of the German authorities I should be liberated and restored to my family.

A SAMPLE OF GERMAN PERFIDY

Antwerpen, 21./5. 15.

Werten Herr Beland!

In diesem Moment erhalte ich Ihren freundlichen Brief vom 19. Ich hoffe, daß Ihre Vorladung beim Meldeamt ein befriedigendes Resultat gehabt hat; ich habe nochmals mit dem Vorstand des Meldeamtes gesprochen und höre, daß Sie diese Unannehmlichkeiten einer Denunziation zu verdanken haben.

Die Sache ist jetzt in Ordnung und wird sich nicht wiederholen.–

ergebenst

Von J. Wilm

Major.

TRANSLATION

Antwerp, May 21st, 1915.

Dear M. Beland!

I receive at this moment your kind letter of the 19th.

I hope that your appearance before the Police Bureau has had a satisfactory outcome; I have spoken once more with the head of the Police Control office and I learn that you owe this inconvenience to a denunciation and it will never occur again.

Sincerely

(signed) Von J. Wilm

Major.

One can easily come to believe what one fervently desires. I deluded myself with the hope that my sojourn in this hotel was only temporary.

A young officer was ordered to accompany me to the Grand Hotel. On the way he allowed me to stop at a stationer’s store long enough to buy a few books. Shortly afterwards we arrived at the hotel.

Every public hall had been converted into military offices. The officer who accompanied me, having exchanged a few words with some of the soldiers, the latter glanced at me as though I were a curious animal.

“He must be an Englishman–yes, he’s English, all right,” several of those repeated in turn, all the time staring at me unsympathetically.

Finally I was conducted to the topmost floor of the hotel and there shown into a room. I was locked in and a sentry kept guard outside. My jailers had the extreme kindness to inform me that I must take[82] my meals in my room; that I must pay for them and also pay the rent of the room. His German Majesty refused to feed his prisoner of honor!

On the following day, Friday, June 4, my wife arrived at the hotel, more dead than alive. She was, as one may easily imagine, in a state of great nervousness. Before coming she had asked and obtained permission to occupy the room with me and share my imprisonment. Well, as one should bear all things philosophically, and as we were in war times, as many millions of people were much worse off than we might be at this hotel, we accepted the inevitable and settled down to our present little annoyance with perfect resignation.

On the following Saturday the children came to visit us. We saw them enter the courtyard on their way to apply for a permit to see us. As they waited we hailed them from the window. Two soldiers immediately rushed from the office and addressed us with bitter invective because we had dared to speak to our own children and because the children had been[83] “audacious” enough to speak to us! What a terrible provocation that children should exchange greetings with their parents!

The children were cavalierly ejected from the courtyard and we saw them no more that day. But on the following morning, by special permission, they were allowed to speak for a few minutes with us. The same day, at noon, the major visited us in our room, transformed into a jail cell.

His face was gloomy. His whole bearing betrayed much anxiety and uneasiness. He brought us bad news.

“I am desolate,” he said again. “I am heart-broken, but Mr. Beland must leave to-day without fail for Germany.”

Imagine the dismay of my wife and of myself at this abrupt announcement!

I ventured to protest. I reminded the major of the assurances he had previously given me. I repeated to him that in my quality as a physician I ought not to be deprived of my liberty. I asked him why was it that the competent authorities at Berlin had not been informed of the medical[84] services I had been rendering at the hospital and to the civil population since the beginning of the war? Altogether I made a very strong plea in protest against the execution of the latest order.

Perturbed and embarrassed the major mumbled some sort of an explanation. The instructions had “come from someone higher in authority than himself”; he had “tried to explain my case to them,” but they “would not hear him”; “all the British subjects in Germany and occupied territory were to be interned without delay.” The major assumed an air of haughtiness I had not noticed hitherto.

“At two o’clock this afternoon you will have to depart,” he said. “A non-commissioned officer will accompany you to Berlin and thence to Ruhleben.”

Ruhleben is the internment camp for civilians of British nationality. The shadow of a very real sorrow pervaded that room. I did not know what to say. Two hours only remained in which my wife and I might be together. She persisted in her entreaties that she might bear me company[85] to Germany, only to meet with an absolute refusal every time.

The Major had the delicacy (?) to inform her that her company, even to the station merely, was not desirable!

Punctually at two o’clock on June 6 a non-commissioned officer stood in the room to which during the past three days we had become reconciled, as to a new little home where the children, living only a few miles away, might visit us once or twice a week.

All was declared ready for my departure. It was a solemn moment, and profoundly sad. My wife and I were separated. I did not know then–and it was perhaps better–that I should never see her again in this world.

At three o’clock the train arrived at Brussels, where we had to wait for an hour to connect with the express which ran from Lille to Libau in Russia.

By four o’clock we were steaming at a good speed in the direction of Berlin, passing through the country sights of Belgium. We crossed through Louvain, which had been burned, and through a large number[86] of towns and villages which showed the effects of bombardment and other horrors of war; thence through Liege, Aix-la-Chapelle, and Cologne, where we arrived at about nine o’clock.

Overcome by the tidings of what was to be my fate I had no inclination for lunch before I left Antwerp. In the evening I was seized by the pangs of hunger, and as there was a dining-car on the train I suggested to my guardian that we should take dinner.