OUR GREATEST BATTLE

THE VAGABOND

WITH KUROKI IN MANCHURIA

THE LAST SHOT

MY YEAR OF THE GREAT WAR

MY SECOND YEAR OF THE WAR

WITH OUR FACES IN THE LIGHT

AMERICA IN FRANCE

OUR GREATEST BATTLE

BY

FREDERICK PALMER

Author of "The Last Shot," "America in France," etc.

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1919

During the war we had books which were the product of the spirit of the hour and its limitations. Among these was my "America in France," which was written, while we were still expecting the war to last through the summer of 1919, to describe the gathering and training of the American Expeditionary Forces, and their actions through the Château-Thierry and Saint-Mihiel operations. Since the war and the passing of the military censorship, we have had many hastily compiled histories, and many "inside" accounts from participants, including commanders, both Allied and enemy, whose special pleading is, to one familiar with events, no less evident in their lapses than in their tone.

This book, which continues and supplements "America in France," is not in the class of the jerry-built histories or the personal narratives. It aims, as the result of special facilities for information and observation, to give a comprehensive and intelligent account of the greatest battle in which Americans ever fought, the Meuse-Argonne.

In the formative period of our army, I was the officer in charge of press relations, under a senior[vi] officer. I was never chief censor of the A. E. F.: I had nothing to do with the censorship of the soldiers' mail. After we began operations in the field, my long experience in war was utilized in making me an observer, who had the freedom of our lines and of those of our Allies in France. Where the average man in the army was limited in his observations to his own unit, I had the key to the different compartments. I saw all our divisions in action and all the processes of combat and organization. It was gratifying that my suggestions sometimes led to a broader point of view in keeping with the character of the immense new army which was being filled into the mold of the old.

Friends who have read the manuscript complain that I do not give enough of my own experiences, or enough reminiscences of eminent personalities; but even in the few places where I have allowed the personal note to appear it has seemed, as it would to anyone who had been in my place, a petty intrusion upon the mighty whole of two million American soldiers, who were to me the most interesting personalities I met. The little that one pair of eyes could see may supply an atmosphere of living actuality not to be easily reproduced from bare records by future historians, who will have at their service the increasing accumulation of data.

In the light of my observations during the battle,[vii] I went over the fields after the armistice, and studied the official reports, and talked with the men of our army divisions. For reasons that are now obvious, the results do not read like the communiqués and dispatches of the time, which gave our public their idea of an action which could not be adequately described until it was finished and the war was over. We had repulses, when heroism could not persist against annihilation by cross-fire; our men attacked again and again before positions were won; sometimes they fought harder to gain a little knoll or patch of woods than to gain a mile's depth on other occasions. Accomplishment must be judged by the character of the ground and of the resistance.

As the division was our fighting unit, I have described the part that each division took in the battle. The reader who wearies of details may skip certain chapters, and find in others that he is following the battle as a whole in its conception and plan and execution, and in the human influences which were supreme; but the very piling up of the records of skill, pluck, and industry of division after division from all parts of the country, as they took their turn in the ordeal until they were expended, is accumulative evidence of what we wrought.

The soldier who knew only his division, his regiment, battalion, company, and platoon, as he lay in chill rain in fox-holes, without a blanket, under gas,[viii] shells, and machine-gun fire, or charged across the open or up slippery ascents for a few hundred yards more of gains, may learn, as accurately as my information warrants, in a freshened sense of comradeship, how and where other divisions fought. He may think that his division has not received a fair share of attention for its exploits. I agree with him that it has not, in my realization of the limitations of space and of capacity to be worthy of my subject.

There are many disputes between divisions as the result of a proud and natural rivalry, which was possibly too energetically promoted by the staff in order to force each to its utmost before it staggered in its tracks from wounds and exhaustion. One division might have done the pioneer hammering and thrusting which gave a succeeding division its opportunity. A daring patrol of one division may have entered a position and been ordered to fall back; troops of another division may have taken the same position later. There was nothing so irritating as having to withdraw from hard-won ground because an adjoining unit could not keep up with the advance. Towns and villages were the landmarks on the map, with which communiqués and dispatches conjured; but often the success which made a village on low ground tenable was due to the taking of commanding hills in the neighborhood. Sometimes troops, in their eagerness to overcome the fire on their front, found[ix] themselves in the sector of an adjoining division, and mixed units swept over a position at the same time. In cases of controversy I have tried to adjust by investigation and by comparing reports. I must have made errors, whose correction I welcome. To illustrate the full detail of each division's advance would require several maps as large as a soldier's blanket. The maps which I have used are intended to indicate in a general way the movement of each division, and our part on the western front in relation to our Allies.

There may be surprise that I have not mentioned the names of individuals below the rank of division commander, and that I have not identified units lower than divisions. The easy and accepted method would have been to single out this and that man who had won the Medal of Honor or the Cross, and this or that battalion or company which had a theatric part. Indeed, the author could have made his own choices in distinction. I knew the battle too well; I had too deep a respect for my privilege to set myself up in judgment, or even to trust to the judgment of others. Not all the heroes won the Medal or the Cross. The winners had opportunities; their deeds were officially observed. How many men deserved them in annihilated charges in thickets and ravines, but did not receive them, we shall not know until our graves in France yield their secrets.

I like to think that our men did not fight for Crosses; that they fought for their cause and their manhood. A battalion which did not take a hill may have fought as bravely as one which did, and deserve no less credit for its contribution to the final result. So I have resisted the temptation to make a gallery of fame, and set in its niches those favored in the hazard of action, when it was the heroism and fortitude of all which cannot be too much honored. I have written of the "team-play" rather than the "stars"; of the whole—a whole embracing all that legion of Americans at home or abroad who were in uniform during the war. If I have been discriminate about regulars and reserves, and frank about many other things, it is in no carping sense. We fought the war for a cause which requires the truth, now that the war is over.

I regret that it is not possible for me to give due acknowledgment to the many officers of our army who, during the actual campaign and since their demobilization, have facilitated the gathering of my material. For the preparation of the book I am indebted to the continued assistance, both in France and at home, of Mr. George Bruner Parks.

September, 1919.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | A Change of Plan | 1 |

| II | Into Line for Attack | 19 |

| III | New and Old Divisions | 42 |

| IV | The Order of Battle | 51 |

| V | On the Meuse Side | 65 |

| VI | We Break Through | 75 |

| VII | In the Wake of the Infantry | 95 |

| VIII | The First Day | 109 |

| IX | The Attack Slows Down | 129 |

| X | By the Right Flank | 147 |

| XI | By the Left | 168 |

| XII | By the Center | 194 |

| XIII | Over the Hindenburg Line | 223 |

| XIV | Disengaging Rheims | 249 |

| XV | Veterans Drive a Wedge | 266 |

| XVI | Mastering the Aire Trough | 280 |

| XVII | Veterans Continue Driving | 294 |

| XVIII | The Grandpré Gap Is Ours | 309 |

| XIX | Another Wedge | 324 |

| XX | In the Meuse Trough | 340 |

| XXI | Some Changes in Command[xii] | 355 |

| XXII | A Call for Harbord | 376 |

| XXIII | The S. O. S. Drives a Wedge | 391 |

| XXIV | Regulars and Reserves | 413 |

| XXV | Leavenworth Commands | 433 |

| XXVI | Others Obey | 449 |

| XXVII | American Manhood | 472 |

| XXVIII | The Mill of Battle | 485 |

| XXIX | They Also Served | 501 |

| XXX | Through the Kriemhilde | 515 |

| XXXI | A Citadel and a Bowl | 540 |

| XXXII | The Final Attack | 571 |

| XXXIII | Victory | 589 |

| FACING PAGE | ||

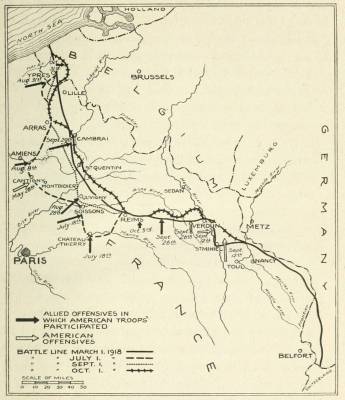

| 1.— | American Offensives and other Offensives | |

| in which American troops participated, | ||

| May-November, 1918 | 2 | |

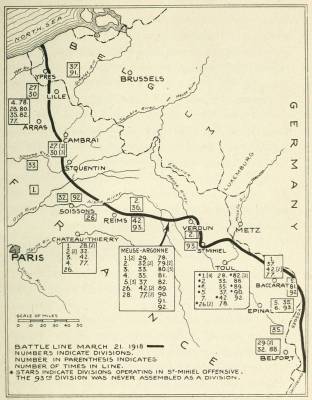

| 2.— | Where American Divisions were in line, | |

| from our entry into the trenches until | ||

| the Armistice | 14 | |

| 3.— | Offensives of September, 1918. Relation | |

| of Meuse-Argonne Battle to the | ||

| decisive Allied offensive movement | 20 | |

| 4.— | Divisions in the First Stage of the | |

| Meuse-Argonne Battle, September | ||

| 26th-October 1st | 52 | |

| 5.— | Divisions in the Second Stage of the | |

| Meuse-Argonne Battle, October 1st-31st | 194 | |

| 6.— | Lines reached by German and Allied | |

| Offensives, 1918 | 224 | |

| 7.— | In the Trough of the Aire | 266 |

| 8.— | The approach of the Center to the | |

| Whale-back | 274 | |

| 9.— | Divisions east of the Meuse | 348 |

| 10.— | The Services of Supply: Showing Ports | |

| and Railroad Communications | 378 | |

| 11.— | Divisions in the Third Stage of the | |

| Meuse-Argonne Battle, October 31st-November | ||

| 11th | 590 |

The original scope of Saint-Mihiel—A winter of preparation for a spring campaign—Which is cut down to two weeks—The tide turning for the Allies—The advantage of a general attack—And especially of numbers—The tactician's opportunity—Why the Meuse-Argonne—The whale-back of Buzancy—Striking for the Lille-Metz railway—All advantage with the defense—The audacity of the enterprise—The handicaps—A thankless task at best.

We were in the fever of preparation for our Saint-Mihiel attack. Divisions summoned from the victorious fields of Château-Thierry, and divisions which had been scattered with the British and French armies, were gathering in our own sector in Lorraine. The French were to assist us with ample artillery and aviation in carrying out our first ambitious plan under our own command.

After cutting the redoubtable salient, which had been a wedge in the Allied line for four years, we were to go through to Mars-la-Tour and Etain, threatening the fortress of Metz itself. This was[2] to be the end of our 1918 campaign. Instead of wasting our energy in operations in mud and snow, we should spend the winter months in applying the lessons which we had learned in our first great battle as an army. Officers who had been proved unfit would be eliminated, and officers who had been proved fit would be promoted. All the freshly arrived divisions from home camps and all the personnel for handling the artillery, tanks, and other material of war which our home factories would then be producing in quantity, would be incorporated in a homogeneous organization.

MAP NO. 1

AMERICAN OFFENSIVES AND OTHER OFFENSIVES IN

WHICH AMERICAN TROOPS PARTICIPATED, MAY-NOVEMBER,

1918.

The spring would find us ready to play the part which had been chosen for us in the final campaign. On the left of the long line from Switzerland to the North Sea would be the British Army, striking out from the Channel bases; in the center the French Army, striking from the heart of France; and on the right the American Army, its munitions arriving in full tide to support its ceaseless blows, was to keep on striking toward the Rhine until a decision was won.

In the early days of September, with our troops going into position before the threatening heights of the salient, and with the pressure of the effort of forming in time an integral army increasing with the suspense as the 12th, the day set for the attack, drew near, some important officers, at the moment when their assistance seemed invaluable, were detached[3] from the Saint-Mihiel operations. Their orders let them into a portentous secret. They were to begin work in making ready for the Meuse-Argonne attack. While all the rest of the army was thinking of our second offensive as coming in the spring of 1919, they knew that it was coming two weeks after the Saint-Mihiel offensive.

This change of plan was the result of a conference between Marshal Foch and General Pershing which planned swift use of opportunity. The German Macedonian front was crumbling, the Turks were falling back before Allenby, and the Italians had turned the tables on the Austrians along the Piave. Equally, if not more to the point for us, the Anglo-French offensive begun on August 8th had gained ground with a facility that quickened the pulse-beat of the Allied soldiers and invited the broadening of the front of attack until, between Soissons and the North Sea, the Germans were swept off Kemmel and out of Armentières and away from Arras and across the old Somme battlefield.

The communiqués were telling the truth about the Allies' light losses; at every point the initiative was ours. The Germans were paying a heavier price in rearguard action than we in the attack. It was a surprising reaction from the pace they had shown in their spring offensives. All information[4] that came through the secret channels from behind the enemy lines supported the conviction of the Allied soldiers at the front that German morale was weakening.

Ludendorff, the master tactician, was facing a new problem. That once dependable German machine was not responding with the alacrity, the team-play, and the bravery which had been his dependence in all his plans. He had to consider, in view of the situation that was now developing, whether or not the Saint-Mihiel salient was worth holding at a sacrifice of men. He knew that we were to attack in force; he knew that in an offensive a new army is bound to suffer from dispersion and from confusion in its transport arrangements. If he allowed us to strike into the air, he could depend upon the mires of the plain of the Woëvre to impede us while the defenses of Metz would further stay our advance, with the result that his reserves, released from Saint-Mihiel, might safely be sent to resist the pressure on the Anglo-French front, either in holding the Hindenburg line or in the arduous and necessarily deliberate business of covering his withdrawal to a new and shorter line of defense based on the Meuse River. The German war machine, which had been tied for four years to its depots and other semi-permanent arrangements for trench warfare, could not move at short notice.

A generalization might consider the war on the Western Front as two great battles and one prolonged siege. For the first six weeks there had been the "war of movement," as the French called it, until the Germans, beaten back from the Marne, had formed the old trench line. Throughout the four years of siege warfare that had ensued, the object of every important offensive, Allied and German, had been a return to the "war of movement." After a breach had been made in the fortifications, the attacking army would make the most of the momentum of success in rapid advances and maneuvers, throw the enemy's units into confusion, and, through the disruption of the delicate web of communications by which he controlled their movements for cohesive effort, precipitate a disaster. The long preparations which had preceded the offensives of 1915, 1916, and 1917 had always given the enemy ample warning of what to expect. He had met concentrations for attack with concentrations for defense. The sector where the issue was joined became a settled area of violent siege operations into which either side poured its fresh divisions as into a funnel. Succeeding offensives, in realization of the limitations of a narrower sector,—which only left the advance in a V with flanks exposed,—had broadened their fronts of attack; but none had been broad enough to permit of vital tactical surprises after the[6] initial onset. The attrition of the man-power of the offensive force had so kept pace with that of the defensive that the offensive had never had sufficient reserves to force a decision when the reserves of the defensive were approaching exhaustion. Moreover, the Allies had never had sufficient preponderance of men, ordnance, and munitions to warrant undertaking the enterprise, which was the dream of every tactician, of several offensives at different points of the front at the same time or in steady alternation.

Now from Soissons to the sea the French and British were developing a comprehensive movement of attacks, now here and now there, in rapid succession. This drive was not a great impulse that died down as had previous Allied offensives, but a weaving, sweeping, methodical advance. Not only was German morale weakening and ours strengthening, but attrition was now definitely in our favor. Ludendorff's reserves were all in sight. His cards were on the table; we could feel assured that we knew fairly well how he would play them. Our own hand was being reinforced by three hundred thousand men a month from the immense reserves in the American training camps. We could press our initiative without fear of being embarrassed by serious counter-attacks taking advantage of our having overextended ourselves.

Thus far, however, the Germans were still in possession of their old trench system, except at a few points; our counter-offensive had only been recovering the ground which the Germans had won in their spring and summer offensives. Now that the tide had turned against him, Ludendorff, if his situation were as bad as we hoped, had two alternatives, and a third which was a combination of the two. One was to fall back to the proposed shorter line of the Meuse. This would give him the winter for fortifying his new positions. As a shorter front would allow him deeper concentrations for defense and the Allies less room for maneuvers in surprise, it must be their purpose to prevent his successful retreat by prompt, aggressive, and persistent action. The other alternative was to make a decisive stand on the old line, where for four years the Germans had been perfecting their fortifications. If we should overwhelm them when he was holding them rigidly, we should have the advantage of a wall in fragments when it did break. The third plan was to use the old fortifications as a line of strong resistance in supporting his withdrawal. Broadly, this was the one that he was to follow.

Everything pointed to the time as ripe for the fulfilment for the Allies of the tactical dream which had called Ludendorff to his own ambitious campaign in the spring of 1918. Marshal Foch would[8] now broaden his front of alternating attacks from Verdun to the North Sea, in the hope of freeing the Allied armies from trench shackles for a decisive campaign in the open. The American part in this bold undertaking was to be its boldest feature.

If a soldier from Mars had come to Earth at any time from October, 1914, to October, 1918, and had been shown on a flat map the fronts of the two adversaries, he would have said that the obvious strategic point of a single offensive would be between the Meuse River and the Argonne Forest. This would be a blow against the enemy's lines of communication: a blow equivalent to turning his flank. If the soldier from Mars had been shown a relief map, he would have changed his mind, and he would have perfectly understood, as a soldier, why all the offensives had been in the north, from Champagne to Flanders, where breaking through the main line of defenses would bring the aggressor to better ground for his decisive movement in the open. He would also have understood why the front from the Argonne to the Swiss border had been tranquil since the abortive effort of the Germans at Verdun.

When Ludendorff undertook his great offensive of March, 1918, he did not repeat Falkenhayn's error, but turned to the north, where the Allies had made[9] their attacks. In that Lorraine-Alsatian stalemate to the south, with the Vosges mountains and interlocking hills from Switzerland to the forts of Metz as the stronghold of the Germans, and the forts of Verdun, Toul, Epinal, and Belfort as the strongholds of the French, the odds were apparently too much against an offensive by either side to warrant serious consideration. Yet a watch was kept. Over the French mind was always the shadow of a possible German offensive toward Belfort; and, when the sector which our young army was to hold in Alsace and Lorraine had been first discussed in July, 1917, the French excluded the defense of a portion of the front opposite Belfort, with the polite explanation that they preferred to hold that themselves. But the Germans never did more than make the feint of an offensive in the south, which Ludendorff used in the winter of 1918 to draw off French troops and guns from the north: for the army with the numbers and the initiative of offense can always force the defense to waste movements to meet threats of attack. This was another advantage which the Allies could now use in keeping Ludendorff in doubt as to where our real blows were to be struck.

The heights of the Saint-Mihiel salient, which look directly across the plain of the Woëvre to the fortress of Metz, may be said roughly to have formed[10] the left flank of the Lorraine-Alsatian stalemate. They continue onward in the hills which are crowned by the forts of Verdun, and then across the Meuse River for a distance of twenty miles through the bastion of the Argonne Forest, where they gradually break into the more rolling country of Champagne. The Meuse winds past Saint-Mihiel and through the town of Verdun, and then, in its devious course, swings gradually to the northwest until, at Sedan, it turns full westward.

Our new offensive was to be between the Meuse River and the western edge of the Argonne Forest. East of the forest is the little river Aire, and between its valley and the valley of the Meuse rises back of the German front a whale-back of heights, as I shall describe them for the sake of bringing a picture to mind, though the comparison is not absolute. The practical summit of the whale-back is to the eastward of the village of Buzancy. We may use Buzancy as a symbol: for it is only in a highly technical history that the detail of names, confusing to the general and even the professional reader, is warrantable. The summit of the whale-back gained, you are looking down an apron of rolling ground and small hills toward the turn of the Meuse westward past Sedan, where the German Army surrounded the French Army in the Franco-Prussian War.

To the northeast, readily accessible to attack, are the Briey iron-fields, which were invaluable to the Germans for war material. Along the valley of the Meuse after it turns westward, and along the Franco-Belgian frontier runs the great railroad from Metz to Lille, which is double-track all the way and in large part four-track. Incidentally this connected the coal fields of northern France with Germany, but its main service was to form the western trunk line of communication for the German armies in Belgium and northern and eastern France. It was linked up with the railways spreading northward into Belgium and southward toward Amiens and Paris in the arterial system which gave its life blood to the German occupation. If this road were cut, the German troops in retreat would have to pass through the narrow neck of the bottle at Liége.

The dramatic possibilities of gaining the heights of Buzancy and bringing the Lille-Metz tracks under artillery fire had the appeal of a strategic effect of Napoleonic days. The German staff had been fully aware of the danger when, in their retreat after their repulse on the Marne, which the world saw only as the spectacle of the French Army inflicting a defeat on an advancing foe, it used its tactical opportunity for choosing, with comparative deliberation, advantageous defensive positions from the Argonne[12] Forest to the Meuse at the foot of the whale-back.

For future operations it was depending upon more than the elaborate fortifications of that line. Every hundred yards from the foot of the whale-back to the summit was in its favor in resisting attack. Higher ground leads to still higher ground, not in a regular system of ridges but in a terrain where nature cunningly serves the soldier. Nowhere might the defense invite the attack into salients with a better confidence, or feel more certain of the success of his counter-attacks. All roads, and all valleys where roads might be built, were under observation. Heights looked across to heights on either side of the two river troughs, heights of every shape from sharp ridges and rounded hills to peaked summits crowned by woods. Tongues of woods ran across valleys. Patches of woods covered ravines and gullies where machine-gunners would have ideal cover and command of ground. Reverse slopes formed walls for the protection of the artillery. The attack must fight blindly; the defense could fight with eyes open.

Had the Allies attempted an offensive in the Meuse-Argonne sector in the first four years of the war, the long and extensive preparations then regarded as requisite for an ambitious effort against first-line fortifications would have warned the Germans in time to make full use of their positions in[13] counter-preparations. All the advantage of railroads and highways were with them in concentrating men and material. It might not be a long distance in miles from the Argonne line to the Lille-Metz railway or to the Briey iron-fields, but it was a long distance if you were to travel it with an army and its impedimenta against the German Army in its prime. When attrition was in his favor in the early period, the German might well have preferred that the Allied offensive of Champagne, or Loos, or the Somme, or Passchendaele, should have been attempted here: thus leaving open to him, after he had inflicted a bloody repulse in this sector, the better ground in the north for a telling counter-offensive.

Thus an Allied effort toward Mézières, Sedan, and Briey would have been madness until the propitious moment came. Had it really come now? Anyone who was familiar with the history of warfare on the Western Front might ask the question thoughtfully. Bear in mind that we had not yet taken Saint-Mihiel and were not yet certain of our success there; and that from Soissons to Switzerland the old German line was intact. North of Soissons we had broken into it at only a few points. In the event that they had had to make a strategic withdrawal, the Germans had always followed the tactical system of a full recoil to strong chosen positions,[14] where they resisted with sudden and terrific violence and held stubbornly and thriftily until they began one of their powerful counter-thrusts.

MAP NO. 2

WHERE AMERICAN DIVISIONS WERE IN LINE, FROM OUR

ENTRY INTO THE TRENCHES UNTIL THE ARMISTICE.

Thus they had fallen back after their defeat on the Marne, from before Warsaw, and from Bapaume to the Hindenburg line. Again and again their morale had been reported breaking, and they had seemed in a disadvantageous position, only to recover their spirit as by imperial command and to extricate themselves in a reversal of form. The German Staff was still in being; the German Army still had reserve divisions and was back on powerful trench systems with ample artillery, machine-guns, and ammunition. Whether Ludendorff was to stand on the old line or withdraw to a new line, either operation would be imperiled by the loss of those heights between the Argonne and the Meuse. He must say, as Pétain had said at Verdun: "They shall not pass!"

In my "America in France" I have told of our project, formed in June, 1917, when we had not yet a division of infantry in France and submarine destruction was on the increase, for an army of a million men in France, capable of the expansion to two million which must come, General Pershing thought, before the war could be won. That far-sighted conception and the decision which was now taken are the two towering landmarks of the troublous road of our effort in France. By July 1st, 1918, we had a million men in France, or nearly double the number of the schedule arranged between the French and American governments. We should soon have two millions.

When the Allies called for more man-power, in the crisis of the German offensive of March, 1918, the British had supplied the shipping that brought the divisions from our home training camps tumbling into France. They were divisions, not an army; and in equipment they were not even divisions. They had been hurried to the front to support the British and French as reserves, and they had been thrown into battle to resist the later German offensives. There had been no niggardliness in our attitude. We offered all our man-power as cannon-fodder to meet the emergency. Across the Paris road behind Château-Thierry we had given more than the proof of our valor. In the drive toward Soissons and to the Vesle we had established our personal mastery over the enemy. We had pressed him at close quarters, and kept on pressing him until he had to go. The confidence inherent in our nature, strengthened by training, had grown with the test of battle. We had known none of the reverses which lead to caution. More than ever our impulse was to attack.

Château-Thierry had taught Marshal Foch that[16] he could depend upon any American division as "shock" troops which would charge and keep on charging until exhausted. Now he would use this quality to the utmost. To the American Army he assigned the part which relied upon the call of victory to soldiers as fresh as the French on the Marne, and, in their homesickness for their native land, impatient for quick results. If a Congressional Committee, knowing all that General Pershing knew, had been told of the plan of the Meuse-Argonne, they would probably have said: "No leader shall sacrifice our men in that fashion. We will not stand by and see them sent to slaughter."

The reputation of a commander was at stake. Should we break through promptly to the summit of the heights, then we might take divisions, corps, even armies, prisoners; but that was a dream dependent upon a deterioration in German staff work and in the morale of the German soldier which was inconceivable. The great prize was the hope of an early decision of the war; in expending a hundred or two hundred thousand casualties in the autumn and early winter, instead of a million, perhaps, during the coming summer. At home we should be saved from drafting more millions of men into our army; from the floating of more liberty loans; from harsher restrictions upon our daily life; from the calling of more women and children to[17] hard labor; from the prolongation of the agony, the suspense, the horror, and the costs of the cataclysm of destruction.

There were more handicaps than the heights to consider: those of our unreadiness. If we had failed, this would have meant the burden of criticism heavy upon the shoulders of the commander-in-chief, who would have been recalled. Dreams of any miraculous success aside, it was not the example of the swift results in a day at Antietam, or the brilliant maneuver of Jackson at Chancellorsville, but the wrestling, hammering, stubbornly resisting effort of the men of the North and South in the Appomattox campaign which was to call upon our heritage of fortitude. In that series of attacks which Marshal Foch was now to develop, our part as the right flank of the three great armies was in keeping with the original plan of 1917: only we were facing the Meuse instead of the Rhine. Without sufficient material or experience, we were to keep on driving, not looking forward to the dry ground and fair weather of summer but toward the inclemency of winter. There against the main artery of German communications we were to launch a threat whose power was dependent upon the determined initiative of our men. Every German soldier killed or wounded was one withdrawn from the fronts of the British and French, or from Ludendorff's reserves[18] which must protect his retreat; and every shell and every machine-gun bullet which was fired at us was one less fired at our Allies. It was to be in many respects a thankless battle, and for this reason it was the more honor to our soldiers.

The Meuse-Argonne and the Somme Battle of 1916—The British had four months of preparation—And a trained army—But a resolute enemy—Our untried troops—Outguessing Ludendorff—Prime importance of surprise—Blindman's buff—What it means to move armies—Fixing supply centers—Staffs arrive—Their inexperience—Learning on the run—Our confidence—Aiming for the stars—Up on time.

Comparisons with the Battle of the Somme, the first great British offensive, which I observed through the summer of 1916, often occurred to me during the Meuse-Argonne battle. In both a new army, in its vigor of aggressive impulse, continued its attack with an indomitable will, counting its gains by hundreds of yards, but never for a moment yielding the initiative in its tireless attrition.

The British were four months in preparing for their thrust on the basis of nearly two years' training in active warfare, with all their arrangements for transport and supply settled in a small area only an hour's steaming across the Channel from home. Behind their lines they built light railroads and highways. They had ample billeting space, and their great hospitals were within easy reach. They[20] gathered road-repairing machinery and trained their labor battalions; built depots and yards; established immense dumps of ammunition and engineering material; brought their heavy guns into position methodically, and registered them with caution over a long period; set an immense array of trench mortars in secure positions; dug deep assembly trenches for the troops to occupy before going "over the top"; and ran their water pipes up to the front line, ready for extension into conquered territory.

MAP NO. 3

OFFENSIVES OF SEPTEMBER, 1918. RELATION OF MEUSE-ARGONNE

BATTLE TO THE DECISIVE ALLIED OFFENSIVE

MOVEMENT.

Their divisions had been seasoned by long trench experience, tested in the terrific fire of the Ypres salient and trained in elaborate trench raids for a great offensive. All their methods were as deliberate as British thoroughness required. Units were carefully rehearsed in their parts, and their liaison worked out by staffs that had long operated together. Commanders of battalions, brigades, and divisions had been tried out, and corps commanders and staffs developed.

On the other hand, the Germans knew that the British attack was coming. Their army was in the prime of its numbers and efficiency. They had immence forces of reserves to draw upon to meet an offensive which was centered in one sector, with no danger of having to meet offensives in another sector. We were striking in one of several offensives, each having for its object rapidity and suddenness of execution, over about the same breadth of front as the British in 1916; and against[21] the Germans, not in their prime, as I have said, but when they had lost the initiative and were deteriorating.

The increase of the skill of infantry in the attack, in their nicely calculated and acrobatic coördination with protecting curtains of accurate artillery fire, had been the supreme factor in the progress of tactics. As a young army we had all these lessons to learn and to apply to our own special problems. As we could not use the divisions that were at Saint-Mihiel in the initial onset in the Meuse-Argonne, we had to depend upon others from training camps and upon those which were just being relieved from the Château-Thierry area. Two of them had never been under fire; several had had only trench experience. They had not fought or trained together as an army. Many of our commanders had not been tried out. Some of the divisions were as yet without their artillery brigades; others had never served with their artillery brigades in action. By the morning of September 25th, or thirteen days after the Saint-Mihiel attack, all the infantry, the guns, the aviation, and the tanks must be in position to throw their weight, in disciplined solidarity, against a line of fortifications which had all the strength[22] that ant-like industry could build on chosen positions.

We had neither material nor time for extensive preparations. We must depend upon the shock of a sudden and terrific impact and the momentum of irresistible dash. If we took the enemy by surprise when he was holding the line weakly with few reserves, we might go far. Indeed, never was the element of surprise more essential. We were countering Ludendorff's anticipation that, if he withdrew from the salient, we should stall our forces ineffectually in the mud before Metz: countering it with the anticipation that he would never consider that a new army, though it grasped his intention, would within two weeks' time dare another offensive against the heights of the whale-back.

For our dense concentrations we had only two first-class roads leading up to the twenty-mile front between the Meuse and the Forest's edge. These were ill placed for our purpose. We might form our ammunition dumps in the woods, but nothing could have been more fatal than to have built a road, for to an aviator nothing is so visible as the line of a new road. Where aviators were flying at a height of twelve thousand feet in the Battle of the Somme, they were now flying with a splendid audacity as low as a thousand feet, which enabled them to locate new building, piles of material, even[23] well-camouflaged gun positions; and the minute changes in a photograph taken today in comparison with one of yesterday were sufficient evidence to a staff expert that some movement was in progress. An unusual amount of motor-truck traffic or even an unusual number of automobiles, not to mention the marching of an unusual number of troops along a road by day, was immediately detected.

All our hundreds of thousands of men, all the artillery, all the transport must move forward at night. To show lights was to sprinkle tell-tale stars in the carpet of darkness as another indication that a sector which had known routine quiet for month on month was awakening with new life that could mean only one thing to a military observer. With the first suspicion of an offensive the enemy's troops in the trenches would be put on guard, reserves might be brought up, machine-guns installed, more aviators summoned, trench raids undertaken, and all the means of information quickened in search for enlightening details.

It was possible that the German might have learned our plan at its inception from secret agents within our own lines. If he had, it would not have been the first time that this had happened. In turn, his preparations for defense might be kept secret in order to make his reception hotter and more crafty. He might let the headlong initiative of our troops[24] carry us into a salient at certain points before he exerted his pressure disastrously for us on our flanks. Thus he had met the French offensive of the spring of 1917; thus he had concentrated his murder from Gommecourt to La Boisselle in the Somme Battle.

Not only had our army to "take over" from the French in all the details of a sector, from transport and headquarters to front line, but the Fourth French Army, on our left, which was to attack at the same hour, must be reinforced with troops and guns. The decision that the Saint-Mihiel offensive was not to follow through to Etain and Mars-la-Tour meant that French as well as American units and material must move from that sector to the Argonne. Immediately it had covered the charge of our troops the heavy artillery, both French and American, was to be started on its way, and, after it, other artillery and auxiliary troops and transport of all kinds as they could be spared.

"It sounds a bromide to say that you cannot begin attacking until your army is at the front," said a young reserve officer, "but I never knew what it meant before to get an army to the front."

He had studied his march tables at the Staff School at Langres; now he was applying them. Young reserve officers had a taste of the difficulties of troop movements. They had to locate units, see[25] that they received their orders, and set them on their way according to schedule, with strict injunctions from "on high" to see that everybody was up on time. They had lessons in the speed of units and the capacity of roads which, at the sight of a column of soldiers on the march, will always rise in their recollections of anxious days.

When haste is vital, unexpected contingencies due to the uneven character of men and materials break into any system. That is the "trouble" with war, as one of these young officers said. Everything depends upon system, and system is impossible when the very nature of war develops unexpected demands that are prejudicial to any dependable processes of routine. With urgent calls for locomotives and rolling stock coming from every quarter to meet the demands of the extension of the Allied offensive campaign over an unexampled breadth of front, the railroads, which were few in this region, could not transport troops and artillery which ordinarily would have gone by train.

Three road routes were available from the Saint-Mihiel to the Argonne region. Artillery tractors that could go only three were in columns with vehicles that could go ten and fifteen miles an hour. Field artillery regiments, coming out from the Saint-Mihiel sector after two weeks of ceaseless travail, were delayed by having their horses killed by shell-fire.[26] The exhaustion of horses from overwork was becoming increasingly pitiful. They could not have the proper rest and care. In some instances they made in a night only half the distance which schedules required. When the deep mud, and outbursts of bombardment from the enemy, retarded the relief of troops, motor buses, which were waiting for them, had to be dispatched on other errands, leaving weary legs to march instead of ride. Military police, army and corps auxiliaries of all kinds, and various headquarters must be transferred.

Officers who had hoped for a little sleep once the Saint-Mihiel offensive was under way received "travel orders," with instructions to reach the Argonne area by hopping a motor-truck or in any way they could. Soldiers, after marching all night, might seek sleep in the villages if there were room in houses, barns, or haylofts. Blocks of traffic were frequent when some big gun or truck slewed into a slough in the darkness.

The processions on these three roads from Saint-Mihiel represented only one of many movements from all directions to the Argonne sector. French units had to pass by our new front to that of the Fourth Army. A French officer at Bar-le-Duc, who had charge of routing all the traffic, was an old hand at this business of moving armies. He perfectly appreciated that curses were speeding toward his[27] office from all four points of the compass where traffic was stalled or columns waited an interminably long time at cross-roads for their turn to move, or guns or tanks or anything else in all the varied assortment were not arriving on schedule time. By telephone he kept in touch with American and French units in the process of the mobilization, while he moved his chessmen on the rigid lines of his map.

The "sacred road" from Bar-le-Duc to Verdun coursed again with the full tide of urgent demands; only this time the traffic turned off on the roads to the left instead of going on to the town. With each passing day, as the concentration increased, daylight became a more portentous foe. "No lights! No lights!" was the watchword of all thought which the military police spoke in no uncertain tones to any chauffeur who thought that one flash of his lamps would do no harm; some of the language used was brimstone and figuratively illuminating enough to have made an aurora borealis. Camouflage became an obsession of everyone who had any responsibility. Discomfort, loss of temper and of time were the handicaps in this blind man's buff of trying to keep the landscape looking as natural by day as it had in the previous months of tranquil trench warfare.

Traffic management was only one and not the[28] most trying or important part of the problem. If the demands upon the Services of Supply were not met, failure was certain: our army would be hungry and without ammunition. In no department was the additional burden of the Meuse-Argonne more keenly felt than in this. New railheads must be established, and additional vehicular transport sent forward to connect up with the new front. Though the mastering of the objective in the Saint-Mihiel operation released a certain surplus, it was disturbingly small. The line established after the salient was cut had become violent. It would require large quantities of supplies as long as we should hold it; and it was already evident that the Meuse-Argonne offensive was to be a greedy monster which could never have its hunger satisfied.

Every hour that we kept the enemy ignorant of the strength of our concentration was an hour gained. The one thing that he must not know was the number of divisions which we were marshaling for our effort. They were the sure criterion of the formidability of our intentions. The most delicate task of all was the taking over of the front line from the French. Not until the stage was set with the accessories of the heavy artillery, the new depots, and ammunition dumps did the roads near the front, cleared for their progress, throb under the blanket of night with the scraping rhythm of the doughboys'[29] marching steps, infusing in the preparations the life of a myriad human pulse-beats in unison. Our faith was in them, in the days before the battle and all through the battle to the end. Their faces so many moving white points in the darkness, each figure under its heavy equipment seemed alike in shadowy silhouette. In the mystery of night their disciplined power, suggestive of the tiger creeping stealthily forward for the spring on his prey, was even more significant than by day.

The men were prepared in the red blood that coursed young arteries, in their litheness and their pride and will to "go to it." They had their rifles, their belts full of ammunition, their gas masks, and their rations. It was not for them to ask any questions—not even if the barrages which would cover their charges would be accurate, if the tanks would kill machine-gun nests, if the barbed wire would be cut, and if their generals would make mistakes. Suspense, not of the mind but of the heart, lightened at the sight of their movement, so automatic and yet so stirringly human. The gigantic preparations of dumps, gun positions, and trains of powerful tractors became only a demonstration of the mighty energy of our industrial age beside that subtler endeavor which had formed them for their task and set them down as the pawns of a staff in a gamble with death. Might the big guns that the troops[30] passed, grim hard shadows in ravines and woods, do their work well in order that the empty ambulances at rest in long lines might have little to do!

By battalions and companies the marching columns separated, taking by-roads and paths, as their officers studied their maps and received instructions from French guides who knew the ground. By daylight they were dissipated into the landscape. The hornets were in their hives; they would swarm as dawn broke to the thunders of the artillery. Attacks were always at dawn; and dawn had taken on a new meaning to us since the morning of July 18th, when our 1st and 2nd Divisions, in the company of crack French divisions, had started the first of the counter-offensives.

The success of Saint-Mihiel had developed corps staffs which must now direct the Meuse-Argonne, while others took over the arrangements at Saint-Mihiel. Major-General Hunter Liggett, pioneer of corps commanders, with the First Corps was to be on the left; Major-General George H. Cameron, with the Fifth Corps in the center; and Major-General Robert L. Bullard, with the Third Corps on the right. Groups of officers making a pilgrimage in automobiles to the new sector were to be the "brains" of the coming attack; for our corps command was an administrative unit which took over the[31] direction of a different set of divisions from those under it at Saint-Mihiel.

The corps staffs had only four or five days for their staff preparations for the battle. It was Army Headquarters in the town hall of Souilly which set the army objective, the corps limits, and the tactical direction of the attack as a whole, while the corps set the divisional limits and objectives to accord with the army objective. At our call we had French experience of the sector, and in this war of maps we had maps. Our prevision in this respect was excellent. The French furnished us with millions of maps in the course of the war; we had our own map-printing presses at Langres; and we had movable presses in the field for printing maps which gave the results of the latest observations of the enemy's defenses. A snowstorm of maps descended upon our army, and still the cry was for more. Not only battalion and company, but platoon and even squad commanders needed these large-scale backgrounds marked with their parts.

Yet maps have their limitations. They may show the ground in much detail, but, even when the blue diagrams and symbols are supposed up to date, not the bushes where the enemy's machine-gun nests are hidden, or what the enemy has done overnight in the way of defenses. Nor are maps plummets into human psychology. Even when they have located[32] machine-gun nests they cannot say whether the gunners who man them will yield easily or will fight to the death. If the British on the Somme, after months of preparation and study of the defenses of the sector, had more elaborate directions for their units than we, it does not mean that, considering its inexperience, our staff did not accomplish wonders.

Our corps commanders may have known their division commanders in time of peace, but they had never been their superiors in action of any kind. Their artillery groupings and aviation arrangements included French units as well as their own. There was no time for considering niceties in dispositions. Division commanders who had to arrange the details of their coöperation had never served together. They had scores of problems, due to the haste of their mobilization, to consider; for the burden of apprehension that pressed them close was of apprehension lest they should not be up on time. They and their officers went over the ground at the front, but they had not the time to make the thorough observation that any painstaking and energetic division commander would have preferred.

A division with all its artillery, machine-guns, and transport is a ponderous column in movement, with every part having its regulation place. One day in one set of villages and the next in another, the communication of orders and requirements down[33] through all the branches is difficult, and the more so when you are short of dispatch riders, and there is a limit to what can be done over the field telephone. The unexpected demand for wires for our second great offensive must not find the signal corps unprepared; or a people as dependent on telephones and telegraph as we are, and so accustomed to having them materialize on request, would have been helpless in making war. The deepest tactical concern was, of course, the coördination of the artillery with the infantry advance. It is only a difference of a hundred yards' range, as we all know, between putting your shells among your own men instead of the enemy's.

Reliable communication from the infantry to the aviator and his reliable report of his observations to the artillery and infantry is one of the complicated features in that team-play, which, in the game of death, needs all the finesse of professional baseball, a secret service, and a political machine, plus the requisite poise, despite poor food and short hours of sleep, for worthily leading men in battle. Some divisions that went into this action had not yet received their artillery; or again their artillery arrived from the training camp, where the guns had just been received, barely in time to go into position, so that an inexperienced artillery commander reported to an inexperienced division commander with whom he[34] had never served. There were batteries without horses, which the horses of other batteries pulled into position after they had brought up their own. Battery commanders received their table of barrages and their objectives of fire, and, without registering, had to trust to observation by men untried in battle or by aviators who had never before observed in a big operation. Aviators had been trained to expect the infantry to put out panels, and they might say that the infantry did not show their panels, while the infantry would deny the charge. Such things had happened before. They would happen this time. They happen to the most veteran of armies, whose long experience, however, may have an excellent substitute in other qualities which we had in plenitude, as we shall see.

All our own guns were of French make, with the exception of a few howitzers. The gun-producing power of the French arsenals supplying us with our artillery and our machine-guns—the Brownings were only just beginning to arrive—in addition to supplying all their own forces over the long front of their offensive was one of the marvels of the war and an important factor in victory. The majority of our planes were also of French make: not until August had the Liberty motors begun to arrive. The French had supplied us with additional aviation and tanks, as well as artillery, from their own army; but[35] much of this was new. All the Allies, indeed, were robbing their training camps for the supreme effort that was about to be made from the Meuse to the Channel.

While the public, which thinks of aviation in terms of combat, admired the exploits of the aces in bringing down enemy planes, which they looked for in the communiqués, the army was thinking of the value of the work of the observers, whose heroism in running the gamut of fire from air and earth in order to bring back information might change the fate of battles. Training for combat, perhaps, more nearly approximated service conditions than training for observation. A fighting aviator, with natural born courage, audacity, and coolness, who goes out determinedly to bring down his man, makes the ace. These qualities were never lacking in our fliers. They went after their men and got them, in a record of successes which was not the least of the honors which our army won in France. The observer had no public praise; he was always the butt of the complaint that he did not bring enough information, or that he brought inaccurate information. His complex responsibilities were singularly dependent upon that experience which comes only from practice.

Instead of applying the lessons of Saint-Mihiel at leisure, as we had hoped, to the whole army, we had[36] to apply them on the run in the rapid concentration of divisions which had not been at Saint-Mihiel. Yet the supreme thing was not schooling. It was a seemingly superhuman task in speed. It was to have the infantry up on time even if the other units were limping. In this we succeeded. On the night of September 24th, from the Meuse to the Forest's western edge every division was in position. We had kept faith with Marshal Foch's orders. We were ready to go "over the top."

The Marshal postponed the attack for another day. Rumor gave the reason that the French Fourth Army was not ready; possibly the real reason, or at least a contributory reason, was in the canniness of such an old hand at offensives as Marshal Foch. Ours was a new army under enormous pressure. Veteran armies were always asking, at the last moment, for more time in which to complete their preparations before attacking. Possibly the Marshal had set the 25th as the date with a view to forcing our effort under spur of the calendar, while he looked forward to granting the inevitable request for delay. At all events the respite was most welcome. Our staff had time for further conferences and attention to their arrangements for supplies, and our combat troops a breathing spell which gave their officers another day in which to study the positions they were to storm.

When I considered all the digging necessary for making the gun positions, or had even a cursory view of the parks of divisional transport, of the reserves crowded in villages and woods, of the ammunition trains, and of the busy corps and division headquarters, I wondered if it were possible that the Germans could not have been apprised that a concentration was in progress. Not only did pocket lamps flash like fireflies from the hands of those who used them thoughtlessly, but despite precautions careless drivers turned on motor lights, and some rolling kitchen was bound to let out a flare of sparks, while the locomotives running in and out at railheads showed streams of flames from their stacks, and here and there fires were unwittingly started. An aviator riding the night, as he surveyed the shadowy landscape, could not miss these manifestations of activity. If he shut off his engine he might hear above the low thunder of transport the roar of the tanks advancing into position, of the heavy caterpillar tractors drawing big guns. When the air was clear and the wind favorable, the increasing volume of sound directed toward the front must have been borne to sharp ears on the other side of No Man's Land. All this I may mention again, without reference to observations by spies within our lines.

On our side, we might try to learn if the enemy knew of our coming, and how much he knew. A[38] thin fringe of French had remained in the front-line trenches, with our men in place behind them. Thus our voices of different timbre, speaking the English tongue in regions where only French had been spoken, might not be heard if we forgot the rules of silence, which were as mandatory by custom as in a church or a library; and besides, if the Germans made a raid for information they would not take American prisoners. They did make some minor raids, capturing Frenchmen who, perhaps unwittingly when wounded or in the reaction from danger, and subject to an intelligence system skilled in humoring and indirect catechism, told more than they thought they were telling. Information that we had from German prisoners left no doubt that the Germans knew at least that the Americans were moving into the sector, but did not expect a powerful offensive. This, as we had anticipated, was discounted as being out of the question on the heels of the Saint-Mihiel offensive. Our new army, the Germans thought, had not the skill or the material for such a concentration, even if we had the troops.

In our demonstration that we did have the skill and the energy, and that in one way and another we were able to secure the material even though it were inadequate, we were peculiarly American; and we were most significantly American in the adaptable[39] exercise of the reserve nervous force of our restless, dynamic natures, which makes us wonderful in a race against time. We strengthen our optimism with the pessimism which spurs our ambition to accomplishment by its self-criticism that is never satisfied.

On all hands I heard complaints by officers concerning lack of equipment, of personnel, of training, and of time. But no one could spare the breath for more than objurgations, uttered in exclamatory emphasis, which eased the mind. I could make a chapter out of these railings. Yet if I implied that the unit, whether salvage or aviation, hospital or front-line battalion, tanks or signal corps, or any other, would not be able to carry out its part, I was assailed with a burst of outraged and flaming optimism. And optimism is the very basis of the psychologic formula of war. Americans have it by nature. We lean forward on our oars. Optimism comes to us from the conquest of a continent. It presides at the birth of every infant, who may one day be president of the United States.

Confidence was rock-ribbed in a commander-in-chief's square jaw; it rang out in voices over the telephone; it was in the very pulse-beats of the waiting infantry; it shone in every face, however weary. We had won at Château-Thierry; we had won at Saint-Mihiel; we should win again. The infantry[40] might not conceive the nature of the defenses or of the fire they might have to encounter. So much the better. They would have the more vim in "driving through," said the staff.

The objectives which we had set ourselves on that first day, after the conquest of the first-line fortifications, which we took for granted, were a tribute to our faith in Marshal Foch's own optimism. On the first day we were striking for the planets. In our second and third days' objectives we did not hesitate to strike for the stars. This plan would give us the more momentum, and if we were to be stopped it would carry us the farther before we were. Of course we did not admit that we might be stopped. If we were not, the German military machine would be broken; and any doubts on the part of generals were locked fast in their inner consciousness, for uttered word of scepticism was treason.

On the night of the 25th, when all the guns began the preliminary bombardment, stretching an aurora from the hills of Verdun into Champagne, our secret was out. From the whirlwind of shells into his positions the enemy knew that we were coming at dawn. With thousands of flashes saluting the heavens it no longer mattered if a rolling kitchen sent up a shower of sparks or an officer inadvertently turned the gleam of his pocket flash skyward. Along the[41] front our infantry slipped forward into the place of the French veterans, who came marching back down the roads.

"Gentlemen," said the French, "the sector is yours. A pleasant morning to you!"

A military machine impossible in human nature—Regular traditions—National Guard sentiment—National Army solidarity—Divisional pride—Our first six divisions unavailable to start in the Meuse-Argonne—British-trained divisions—What veteran divisions would have known.

The Leavenworth plan was to harmonize regulars, National Guard, and National Army into a force so homogeneous that flesh and blood became machinery, with every soldier, squad, platoon, brigade, and division as much like all the others as peas in a pod; but human elements older than the Leavenworth School, which had given soldiers cheer on the march and fire in battle from the days of the spear to the days of the quick-firer, hampered the practical application of the cold professional idea worked out in conscientious logic in the academic cloister. It may be whispered confidentially that all unconsciously their own training and associations sometimes made the inbred and most natural affection of the Leavenworth graduates for the regulars subversive of the very principle which they had set out to practise with such resolutely expressed impartiality. A regular felt that he was a little more[43] of a regular if he were serving with a regular division.

"We're not having any of this good-as-you-are nonsense in this regiment," said its Colonel, talking to a fellow-classman who was on the staff. "We're filled up with reserve officers and rookies,—but we're regulars nevertheless. We've started right with the regular idea—the way we did in the old —th"—in which the officers had served together as lieutenants.

By the same token of sentiment and association the National Guardsmen remained National Guardsmen. They also had a tradition. If they were not proud of it they would be unnatural fighters. While the average citizen had taken no interest in preparedness, except in the abstraction that national defense was an excellent thing, they had drilled on armory floors and attended annual encampments. Sometimes the average citizen had spoken of them as "tin soldiers"; and they were conscious perhaps of a certain superciliousness toward them on the part of regular officers. Drawn from the same communities, members of the same military club that met at the armory, they already had their pride of regiment and of company: a feeling held in common with Guardsmen from other parts of the country, who belonged to the same service from the same motives. Should that old Connecticut or Alabama or any[44] other regiment with a Civil War record, and, perhaps, with a record dating from the Revolution, forget its old number because it was given a new number, or its own armory, because it went to a training camp? Relatives and friends, who bowed to the edict of military uniformity and anonymity, would still think of it as their home regiment. If Minneapolis mixed its sons with St. Paul's, they would still be sons of Minneapolis.

While all volunteers felt that they were entitled to the credit of offering their services without waiting on the call, the draft men, who had awaited the call, had their own conviction about their duty, which, from the hour when they walked over from the railway stations to the camp, gave them a sense of comradeship: while they might argue that it was more honor to found than to follow a tradition. Their parents, sisters, and sweethearts were just as fond, and their friends just as proud, of them as they had been in the Guard. Aside from a few regular superiors, their officers were graduates of the Officers' Training Camps, who, as the regulars said, had nothing to unlearn and were subject to no political associations. Yes, the draft men considered themselves as the national army; and they would set a standard which should be in keeping with this distinction.

All the men assembled in any home cantonment,[45] with the exception of the regulars, were almost invariably from the same part of the country, which gave them a neighborhood feeling. The doings of that cantonment became the intimate concern of the surrounding region. Its chronicles were carried in the local newspapers. There was a division to each cantonment; and in France the fighting unit was the division, complete in all its branches,—artillery, machine-guns, trench mortars, engineers, hospital, signal corps, transport, and other units. As a division it had its training area; as a division it traveled, went into battle, and was relieved.

Before a division was sent to France its men were already thinking in terms of their division; they met the men of no other division unless on leave, and met them in France only in passing, or on the left or right in battle. In the cantonment the division had its own camp newspaper, its own sports, its separate life on the background of the community interest, without the maneuvering of many divisions together on the European plan until they were sent into action in the Saint-Mihiel or Meuse-Argonne offensive. Each division commander and his staff, who were regular officers, conspired to develop a divisional pride, thereby, in a sense, humanly defeating the regular idea of making out of American citizens a machine which could be anything but humanly American. Within the division, pride of company,[46] of battalion, of regiment, was instilled, and the different units developed rivalries which were amalgamated in a sense of rivalry with other divisions.

Every cantonment had the "best" division in the United States before it went to France, where rivalry expressed itself on the battlefield. The record of the war is by divisions. Men might know their division, but not their corps commander. Divisions might not vary in their courage, but they must in the amount of their experience and in the quality of their leaders. A division that had been in three or four actions might be better than one that had been in ten; but a division that had not been in a single action hardly had the advantage over one that had been in several. Our four pioneer divisions, which had been in the trenches during the winter of 1917-18 and later in the Château-Thierry operations, the 1st (regulars), and the 2nd (regulars and marines), and the 26th and the 42nd (both National Guard), were all at Saint-Mihiel. Their units were complete; their artillery had had long practice with their infantry; they had had long training-ground experience in France, had known every kind of action in modern war, and had kept touch under fire, rather than in school instruction, with the progress of tactics. If they were not our "best" divisions, it was their fault.

Of the two other divisions which had been longest[47] after these in our army sector, the 32nd had just finished helping Mangin break through at Juvigny, northwest of Soissons, and the 3rd was at Saint-Mihiel. These six formed the group which General Pershing had in France at the time of the emergency of the German offensive in March, which hastened our program of troop transport.

Now we were bringing to the American army five of the divisions which had been trained with the British, the 4th, 28th, 33rd, 35th, and 77th. From the British front the 77th had gone to Lorraine, whence it was recalled to the Château-Thierry theater. The 4th and the 28th were ordered from the British front, after the third German offensive in June, to stand between Paris and the foe, and then participated, along with the 77th, in the counter-offensive which reduced the Marne salient,—or as the French call it, the second Battle of the Marne, a simple, suggestive, and glorious name. Château-Thierry had thus been a stage in passage from the British to the American sector, and the call for the defense of Paris had been serviceable to the American command as a reason for detaching American divisions, which the British had trained, from Sir Douglas Haig, who, as he is Scotch, was none the less thriftily desirous of retaining them.

The 33rd Division, remaining at the British front after the other divisions had departed, gained experience[48] in offensive operations, as we know, which approximated that of the others at Château-Thierry, when, fighting in the inspiring company of the Australians in the Somme attacks beginning August 8th, the Illinois men took vital positions and numerous prisoners and guns. Though these four divisions, the 4th, 28th, 33rd, and 77th, had not had the long experience of the four pioneer divisions, they had had their "baptism of fire" under severe conditions, they knew German machine-gun methods from close contact, and they had the conviction of their power from having seen the enemy yield before their determined attacks. To Marshal Foch they had brought further evidence that the character of the pioneer divisions with their long training in France was common to all American troops. The National Guard divisions which had arrived late in France, though they had been filled with recruits, had, as the background of their training camp experience at home, not only the established inheritance of their organization but the thankless and instructive service on the Mexican border, where for many months they had been on a war footing.

According to European standards none of the divisions in the first shock of the Meuse-Argonne battle was veteran, of course; and the mission given them would have been considered beyond their powers. Indeed, the disaster of broken units, dispersing[49] from lack of tactical skill, once they were against the fortifications, would have been considered inevitable. A veteran or "shock" division in the European sense—such divisions as the European armies used for major attacks and difficult operations—would have had a superior record in four years of war. Its survivors, through absorption no less than training, would have developed a craft which was now instinctive. They were Europeans fighting in Europe; they knew their enemy and how he would act in given emergencies; they knew the signs which showed that he was weakening or that he was going to resist sturdily; they knew how to find dead spaces, and how to avoid fire; and they had developed that sense of team-play which adjusts itself automatically to situations. All that our divisions knew of these things they had learned from schooling or in one or two battles. We had the advantage that experience had not hardened our initiative until we might be overcautious on some occasions.

The battle order of our divisions for the Meuse-Argonne battle was not based on the tactical adaptation of each unit to the task on its front. We must be satisfied with placing a division in line at a point somewhere between the Meuse and the Forest's edge where transportation most favored its arrival on time. One division was as good as another in a[50] battle arranged in such haste. The French Fourth Army was to attack on the west of the Argonne Forest; on its right a regiment of the 92nd (colored) Division, National Army, with colored officers, was to form the connecting link between the French and the American forces. For men with no experience under heavy fire, who were not long ago working in the cotton fields and on the levees of the South, this was a trying assignment, which would have tested veterans. Never before had colored men under colored officers gone against a powerful trench system. All the British and French colored troops had white officers, and our other colored division, the 93rd, which was attached to the French Army through the summer and fall of 1918, had white officers.

We come now to our divisions in place on the night of September 25th, with whom will ever rest the honor of having stormed the fortifications. When I consider each one's part I should like to write it in full. I shall mention them individually when that best suits the purpose of my chronicle, and at other times I shall describe the common characteristics of their fighting: in either case mindful of the honor they did us all as Americans.

The Metropolitan Division in the Argonne proper—Six weeks without rest—Direct attack impossible in the Forest—Similar history of the Keystone Division—Pennsylvania pride—Its mission the "scalloping" of the Forest edge—The stalwart men of the 35th Division—Storming the Aire heights—Fine spirit of the Pacific Slope Division—A five-mile advance projected for the Ohio Division—North and South in the 79th Division—Never in line before, it was to strike deepest.

Three National Army divisions were to be in the initial attack. It was a far cry for the men who a year before had tumbled into the training camps at home, without knowledge of the manual of arms or of the first elements of army etiquette and discipline, to the march of trained divisions forward into line of battle in France. On the extreme left of the line was the Liberty Division, from New York City. The metropolitans were given the task of taking not a town, but a forest, with which their name will be as long connected as with our largest city. Its left flank on the western edge of the Argonne Forest and its right on the eastern, the 77th had a long divisional front of over four miles; but it would have been unsatisfied if it had had to share the Forest. The Forest was its very own. The public[52] at home seemed to have the idea that the whole battle was fought there. If it had been, the 77th would have had to share credit with twenty other divisions, which had equally stiff fighting in patches of woods which were equally dense even if they were not called forests.

If the Forest were stripped bare of its trees, it would present a great ridge-like bastion cut by ravines, with irregular hills and slopes of a character which, even though bald, would have been formidable in defense. Its timber had nothing in common with the park-like conception of a European forest, in which the ground opens between tree trunks in lines as regular as in an orchard. If the Argonne had been without roads, the Red Indians might have been as much at home in its depths as in the primeval Adirondacks. Underbrush grew as freely as in second-growth woods in our New England or Middle States; the leaves had not yet begun to fall from the trees.

It had not been until September 15th that the 77th had been relieved from the operations in the Château-Thierry region. A new division, fresh from training at the British front and in Lorraine, it had gone into line in August to hold the bank of the Vesle against continuous sniping, gassing, and artillery fire; and later, after holding the bottom of a valley with every avenue of approach shelled in nerve-racking strain, it had shown the mettle of[53] the Americans of the tenements by fighting its way forward for ten days toward the Aisne Canal. It had been in action altogether too long according to accepted standards, though this seems only to have tempered its steel for service in the Argonne.

Ordinarily a new division would not only have been given time to recover from battle exhaustion, which is so severe because in the excitement men are carried forward by sheer will beyond all normal reactions to fatigue, but it would have been given time for drill and for applying the lessons of its first important battle experience. The value of this is the same to a division as a holiday at the mountains or the seashore to a man on the edge of a nervous breakdown. He recovers his physical vitality, and has leisure to see himself and his work in perspective.