Any volume sold separately.

DOTTY DIMPLE SERIES.—Six volumes. Illustrated. Per volume, 75 cents.

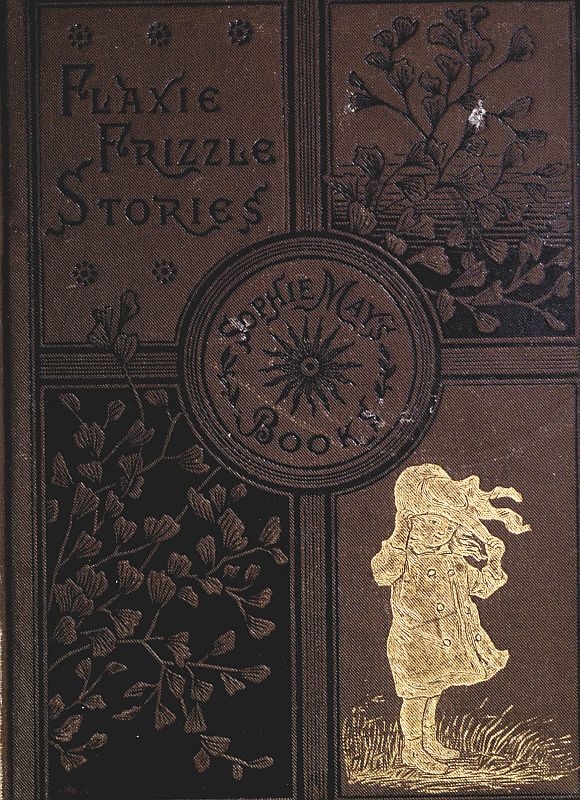

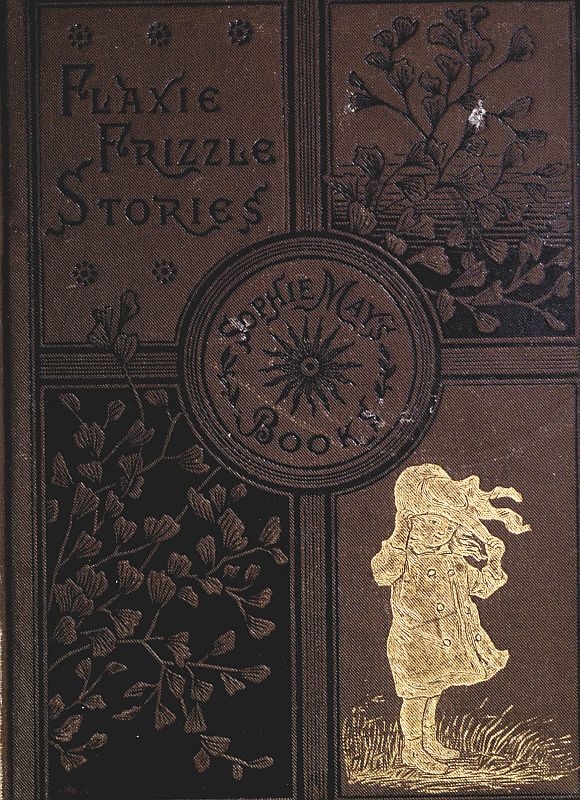

FLAXIE FRIZZLE STORIES.—Six volumes. Illustrated. Per volume, 75 cents.

LITTLE PRUDY STORIES.—Six volumes. Handsomely Illustrated. Per volume, 75 cents.

LITTLE PRUDY’S FLYAWAY SERIES.—Six volumes. Illustrated. Per volume, 75 cents.

————

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS,

BOSTON.

FLAXIE FRIZZLE STORIES

————

Copyright,

1884,

By Lee and Shepard.

———

All Rights Reserved.

———

FLAXIE GROWING UP.

TO

Mary Louise Gibbs.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Punishing Ethel | 7 |

| II. | Asking for “Whiz” | 26 |

| III. | The Spelling School | 43 |

| IV. | The Minister’s Joke | 59 |

| V. | Chinese Babies | 76 |

| VI. | Old Bluff | 91 |

| VII. | Camp Comfort | 109 |

| VIII. | Pudding and Pies | 128 |

| IX. | The Hailstorm | 145 |

| X. | Miss Pike’s Story | 160 |

| XI. | Dining Out | 177 |

| XII. | Christmas at Old Bluff | 191 |

“Stop, Ethel,” said Mary Gray authoritatively, “stop this moment, you are skipping notes.”

The child obeyed gladly, for music was by no means a passion with her, and she especially disliked practising when Mary’s sharp eye was upon her.

“I’m obliged to be severe with you, Ethel, for it never will do to allow you to play carelessly. You are worse than usual this morning, because Kittyleen is waiting in the dining-room. It’s very unfortunate that[8] Kittyleen has to come here in your practising hour, and it makes it pretty hard for me; but what do you think or care about that? If you ever learn to play decently, Ethel Gray, ’twill be entirely owing to me, and your teacher says so. There! run off now and play with Kittyleen; but, remember, you’ll have to finish your practising this afternoon.”

Ethel made her escape, and Mary seated herself in the bay-window at her sewing with a deep sigh of responsibility. Her mother was ill; Julia, the eldest of the family, was confined to her room with headache, and the children had been left in Mary’s care this morning with strict charges to obey her.

“The children” were Philip, a boy of eight and a half, and Ethel, a little girl nearly six; but as Phil was now skating on the pond, and Ethel playing dolls in the[9] dining-room with her young friend, Kittyleen Garland, Mary was free to pursue her own thoughts, and her work was soon lying idly in her lap, while she looked out of the window upon the white front yard facing the river.

There was no one in the room with her but her grandmother, who sat knitting in an easy-chair before the glowing coal fire. Grandma Gray did not seem to grow old. Father Time had not stolen away a single one of her precious graces. He had not dimmed her bright eyes or jarred her gentle voice; the wrinkles he had brought were only “ripples,” and the gray hair he had given her was like a beautiful silver crown.

Grandma looked up from her knitting; Mary looked up from her sewing. Their eyes met, and they both smiled.

“A penny for your thoughts, my child.”

“Oh, I was only thinking, grandma, it does seem as if something might be done to prevent people from calling me Flaxie Frizzle—I’m just worn out with it. It did very well when I was a little child; but now that I’m twelve years old, I ought to be treated with more respect. It’s very silly to call people by anything but their real, true names; don’t you think so? Oh, here comes the Countess Leonora!” cried Mary in a different tone, dropping her work, breaking her needle, and pricking her finger, all in a second of time.

“Who? I didn’t understand you, dear.”

“Oh, it’s only Fanny Townsend, grandma. We have fancy names for each other, we girls, and Fanny’s name is Countess Leonora,” cried Mary, quite unaware that there was anything “silly” in this, or that grandma was amused by her inconsistent remarks.[11] The dear old lady smiled benevolently as a small figure in a brown cloak rushed in, breathless from running. It was not Fanny Townsend and Mary Gray, it seemed, who began to chat together in the bay-window, but the Countess Leonora, and her friend, Lady Dandelina Tangle. Lady Dandelina was telling the Countess that her mother and sister were ill, and that she was left in charge of the castle.

“Don’t you miss your brother Preston so much, Lady Dandelina?”

“Indeed I do, Countess; but young men are obliged to go to college, you know. And I can bear it better because my cousin, Fred Allen, of Hilltop, is with us. He will stay, I don’t know how long, and go to school. I only wish it was my sister Milly!”

“So do I, Lady Dandelina. Oh, I saw that old teacher of ours, Mr. Fling, as I was[12] coming here. He stood on the hotel-piazza talking with Miss Pike.”

“Mr. Fling?” said Mary, laughing. She had dropped her work, for how could she sew without a needle?

“Yes; and said he, ‘How’s your health, Miss Fr-an-ce-s?’ as if I’d been sick. I like him out of school, Dandelina; but in school he used to be sort of hateful, don’t you know?”

“Not exactly hateful,” replied Mary, stealing a glance at grandma. “I call it troublesome.”

“Yes; how he would scold when we got under the seat to eat apples?”

“Oh, I never ate but one apple, Fan, I’m sure I never did. I was pretty small then, too. How queer it is to think of such old times!”

“Why, Flaxie, ’twas only last winter!”

“Are you sure, Fan? I thought ’twas ever so long ago.”

“Your reminiscences are very interesting, my dears,” said grandma, rising. “I wish I could hear more, but I shall be obliged to go up stairs now, and leave your pleasant company.”

As the serene old lady passed out at one door, little Ethel, very much excited, rushed in at another; but the girls, engrossed in conversation, did not look up, and she stood for some time unheeded behind Mary’s chair.

“I want to ask you, Flaxie—” she said.

“Mr. Fling and Miss Pike were talking about a spelling-school,” said Fanny, emerging from “old times” at a bound. “She’s going to have an old-fashioned one out in her school at Rosewood to-morrow night.”

“I want to ask you, Flaxie—” repeated Ethel.

“They ‘choose sides.’ Do you know what that is?”

“No, I’m sure I don’t. I wish Preston was here, and he’d take me out in the sleigh. Miss Pike would let our family go, of course.”

“I want to ask you—” said little Ethel again.

“Why, Ethel, child, I thought you were in the other room,” said Mary impatiently. “Don’t you see, I want to hear about the spelling-school; and it’s so thoughtful and kind of little girls to give big girls a chance to speak!”

But next moment, ashamed of her ill-nature, and remembering her maternal responsibility, she drew Ethel to her side and kissed her.

“Wait a minute, Leonora, till we find out what this means,” said she, surprised to see[15] her usually quiet little sister in this wild state. “Tell me all about it, dear.”

Thus encouraged, Ethel broke forth indignantly, “Kittyleen is very disagreeable! And besides, she knocked me down!”

Fanny began to laugh. “Oh, what a Kittyleen!”

“Hush, Fan,” said Mary, warningly, drawing up her mouth like grandma’s silk “work-pocket.” “It doesn’t seem possible, Ethel. I never heard of Kittyleen’s behaving so before. What had you done to vex her?”

“I—I—knocked her down—first,” confessed Ethel, in low, faltering tones.

And Fanny laughed again.

“Fanny Townsend, do be quiet. I have the care of this child to-day. Ethel, where is Kittyleen?”

“Gone home.”

“Ah. Ethel, Ethel, it will be my duty to punish you. Fanny, can you be quiet?”

“You punish her? Oh dear, that’s too funny!”

“Yes, I have full authority to punish her if I choose,” said Mary, elevating her chin.

She was subject to little attacks of dignity; but instead of being duly impressed, Fanny only laughed the more, while shamefaced little Ethel hid her head and felt that she was trifled with.

“May I ask what amuses you, Miss Townsend?” said Mary, with increased dignity.

“Oh don’t, oh dear, what shall I do? You’re so queer, Flaxie Frizzle!”

“Well, if you go on in this way, I shall be obliged to take Ethel out of the room. Have you no judgment at all, Fanny Townsend?”

“Oh dear, oh dear, I shall die laughing![17] shall have to go home! If you could see just how you look, Flaxie Frizzle! Good-by. I can’t help it,” said Fanny, reeling out of the door.

Mary drew a long sigh. “Now come to me, Ethel. This is a dreadful thing, and you’re a perfectly awful child; but it will not do to speak to mother about it, when she has pneumonia, and a blister on the chest. She said I must take care of you.”

Ethel did not stir. Mary paused and gazed reproachfully across the room at her, not knowing in the least what to say next. She had never before undertaken a case of discipline, and rather wondered why it should be required of her now. But she had been given “full authority over the children,” and what did that mean if she was not to punish them when they did wrong?

To be sure Julia’s headache might be over[18] to-morrow, and Julia could then attend to Ethel; but Mary was quite sure it would not do to wait an hour or a minute; the case must be attended to now. “It is my duty, and I will not shrink from it. I’ll try to act exactly as mamma always does,—not harsh, but sad and gentle,—Ethel, my child, come here.”

“Don’t want to,” said Ethel, approaching slowly and sullenly, drawing her little chair behind her.

“Not that way, dear; mamma never allows you to go all doubled up, dragging your chair like a snail with his house on his back. There, sit down and tell me about it. What made you so naughty?”

“My head aches. Don’t want to talk.”

“Were you playing dolls?”

“Yes. Pep’mint Drop is jiggly and won’t sit up.”

“Peppermint Drop is very old and has rheumatism, Ethel; she was my dolly before ever you were born.”

“Well, my head aches. Don’t want to talk.”

“But you must talk. I’m your mother to-day.”

“You?” Ethel looked up saucily, and Mary felt half inclined to laugh; but when one has the care of a young child one must be firm.

“Ethel, I am your mother to-day. What were you doing with those dolls?”

“Nothing! Kittyleen pulled off Pep’mint’s arm.”

“Yes, and then?”

“Then she was cross.”

“No, no. What did you do to her?”

“Tipped her over.”

“Ethel! Ethel!”

“Well, she tipped me over too.”

“This is perfectly dreadful!” exclaimed Mary, as solemnly as if she had never heard it before. And then she sat in deep thought. What would mamma have done in this case? Did Ethel’s head ache? Possibly. Her cheeks looked hot. Mamma was tender of the children when they were ill, and perhaps would not approve of shutting Ethel in the closet if she had taken cold.

“Ethel,” said Mary in natural tones, “I’m going to be very sweet and gentle. You’ve been extremely to blame, but perhaps Kittyleen may forgive you if you ask her.”

“H’m! Don’t want her to!”

“What! Don’t want her to forgive you?”

“No, I don’t; Kittyleen was bad herself!”

“But you were bad first, Ethel.”

“H’m! If I ask her to forgive me she’ll think she was good!”

Mary looked at stubborn Ethel sorrowfully. Oh, how hard it was to make children repent!

“Perhaps I’d better leave her by herself to think. Mamma does that sometimes.” Then aloud: “Ethel, I’m now going into the kitchen, and I wish you to sit here and think till I come back.”

“No, you mustn’t; my mamma won’t allow you to shut me up, Flaxie!”

“But I’m not shutting you up; I only leave you to think.”

“Don’t know how to think.”

“Yes, you do, Ethel, you think every time you wink.”

“Well, may I wink at the clock then?” asked the child, relenting, for it was one of her delights to sit and watch the minute-hand steal slowly over the clock’s white face.

“Yes, you may, if you’ll keep saying over and over, while it ticks, ‘I’ve been a naughty[22] girl—a naughty girl; mamma’ll be sorry, mamma’ll be sorry.’”

“Well, I will, but hurry, Flaxie; don’t be gone long.”

In fifteen minutes Mary returned to find the child in the same spot; her eyes pinker than ever with weeping.

“Just the way I used to look when mamma left me alone,” thought Mary, encouraged.

“Well, Ethel,” with a grown-up folding of the hands which would have convulsed Fanny Townsend. “Well, have you been thinking, dear?”

“Yes, and I’ll tell mamma about it; I shan’t tell you.”

“Mamma is very sick, my child.”

“Then I’ll tell Ninny.” Ninny was the children’s pet name for Julia.

“No, Ninny has a headache. I’m your mamma this afternoon. And I won’t be[23] cross to you, darling,” added Mary, with humility, recalling some of her past lectures to this little sister.

“Well,” said Ethel faintly, with her apron between her teeth. “I wasn’t very bad to Kittyleen, but if she wants to forgive me I’ll let her.”

“O sweetest, you make me so happy!”

“Don’t want to make you happy,” returned Ethel disdainfully; “don’t care anything about you! But mamma’s sick. And you—won’t you write her a letter?”

“Write mamma a letter?”

“No, Kittyleen, write it with vi’let ink, won’t you, Flaxie?”

The note was very short and written just as Ethel dictated it:

My Affectionate Friend,—I am very sorry I knocked you down first. I will forgive you if you will forgive me.

Ethel Gray.

Ethel meant just this, no more, no less. She was sorry; still, if she had done wrong so had Kittyleen; if she needed forgiveness Kittyleen needed it also.

“Now, put something in the corner,” said she, looking on anxiously, as Mary directed the envelope. “You always put something in the corner of your notes, Flaxie; I’ve seen you, and seen you.”

“Do I? Oh yes, sometimes I put ‘kindness of Ethel’ in the corner, but that is when you carry the note.”

“Put it there now.”

“But are you going to carry the note?”

“No, Dodo will carry it if I give her five kisses.”

“Then, I’ll write ‘Kindness of Dora.’”

“No, no, I’m the one that’s kind, not Dodo,” insisted the child.

And “Kindness of Ethel” it had to be in the corner in large, plain letters.

Dora laughed when she read it, and Mary smiled indulgently.

Kittyleen did not smile, however, for she did not know there was any mistake. She accepted Ethel’s doubtful apology with joy, and made her nurse Martha write in reply, “I forgive you.” And in the left-hand corner of her envelope were the words “Kindness of Kittyleen,” for she supposed that was the correct thing, and she never allowed Ethel to be more fashionable than herself if she could possibly help it.

Mary felt that on the whole her first case of discipline had resulted successfully, and was impatient for to-morrow to come, that her mother might hear of it and give her approval.

Next day Mrs. Gray was somewhat better, and when Mary knocked softly at the chamber door, Julia replied, “Come in.” The little girl had not expected to see her mother looking so pale and ill; and the tears sprang to her eyes as she leaned over the bed to give the loving kiss which she meant should fall as gently as a dewdrop on the petal of a rose. It did not seem a fitting time for the question she had come to ask about the spelling-school. Julia was brushing Mrs. Gray’s hair, and Mary kissed the dark, silken locks which strayed over the[27] pillow, murmuring, “Oh, how soft, how beautiful!”

“Well, my dear,” said Mrs. Gray, with an affectionate smile, which lacked a little of its usual brightness, “how did you get on yesterday with Ethel? She is such a quiet little thing that I’m sure you had no trouble.”

“No trouble!” Mary’s look spoke volumes. “I suspect there’s some frightful revelation coming now,” said Julia. “Did you irritate her, Flaxie?” For Ethel’s quietness was not always to be relied upon. She was like the still Lake Camerino of Italy, which so easily becomes muddy that the Italians have a proverb, “Do not disturb Camerino.” Dr. Gray often said to Mary, when he saw her domineering over her little sister, “Be careful! Do not disturb Camerino.”

“No, indeed, Ninny, I was very patient,” replied Mary with pride. “But for all that I had to punish her!”

Mrs. Gray turned her head on her pillow, and looked at Mary in astonishment.

“Did you think I gave you authority to punish your little sister? That would have been strange indeed! I merely said she and Philip were to obey you during the afternoon.”

Mary felt a sudden sense of humiliation, all the more as Julia had suspended the hairbrush, and was looking down on her derisively—or so she fancied.

“Why, mamma, I must have misunderstood you. I thought it was the same as if I was Julia, you know.”

“Julia is eighteen years old, my child. You are twelve. But what had Ethel done that was wrong?”

Then Mary told of the quarrel with Kittyleen, and the notes which had passed between the two little girls. Though naturally given to exaggeration, she had been so carefully trained in this regard that her word could usually be taken now without “a grain of salt.”

Mrs. Gray looked relieved and amused.

“So that was the way you punished your little sister? I was half afraid you had been shutting her up in the closet, or possibly snipping her fingers, either of which things, my child, I should not allow.”

“No, ma’am.” Mary felt like a queen dethroned.

“You were ‘clothed with a little brief authority’ yesterday, to be sure, but you should have waited till to-day and reported any misbehavior to me, or—if I was too ill to hear it—to Julia.”

“Yes, mamma,” said Mary meekly.

“Not that I blame you for this mistake, dear. You have shown judgment and self-control, and no harm has been done as yet, I hope. Only remember, if you are left to take care of the children again, you are not the one to punish them, whatever they may do.”

“Yes, ma’am,” repeated Mary; but her face had brightened at the words “judgment and self-control.”

“I am afraid Ethel’s repentance doesn’t amount to much,” said Julia.

“I thought of that myself. I’m afraid it doesn’t,” admitted Mary.

She watched the brush as it passed slowly and evenly through her mother’s hair. Her color came and went as if she were on the point of saying something which after all she found it hard to say.

“Mamma, Miss Pike is going to have—spelling-school to-night.”

Mrs. Gray’s eyes were closed; she did not appear to be listening.

“It’s in her schoolhouse at Rosewood, and anybody can go that chooses.”

“Ah?”

“Papa isn’t at home this morning.” A pause. “And Fred Allen and I—Now, mamma, I’m afraid you’ll think it isn’t quite best; but there’s a moon every night now; and did you ever go to an old-fashioned spelling-school, where they choose sides?”

“Flaxie, don’t make that noise with the comb,” said Julia. “I suppose you and Fred would like the horse and sleigh, and Fred hasn’t the courage to ask father; is that it?”

“Oh, may we go, mamma? Please may we go?”

“What, to Rosewood in the evening—two miles?”

“Oh, I wish I hadn’t asked you. I wish I hadn’t asked you; I mean I wish you wouldn’t answer now, not till I tell you something more.”

“Well, I will not answer at all; I leave it to your father.”

“Oh, I don’t mean that; I don’t want you to leave it to papa.”

“Flaxie,” remonstrated Julia, “can’t you see that you are tiring mother?”

“I won’t tire her, Ninny. I only want her to think a minute about Whiz, how old he is and lame. He doesn’t frisk as he used to, does he, mamma? And I’m sure Miss Pike will want me at her spelling-school, we’re such friends. And Fanny Townsend is going, and lots and lots of girls of my age.”

“My dear, I leave it entirely to your father,” said Mrs. Gray wearily.

“Yes, mamma; but if you’ll talk to him first, and say Fred’s afraid to ask him, and—and Whiz is so old——”

Julia frowned and pointed to the door. Mary ought to have needed no second warning. She might have seen for herself the conversation was too fatiguing.

“What does make me so selfish and heedless and forgetful and everything that’s bad,” thought she, rushing down-stairs. “I love my mother as well as Ninny does, and am generally careful not to tire her; but if I once forget they think I always forget, and next thing papa will forbid my going into her room.”

Fred stood by the bay window awaiting his cousin’s report.

“O Fred, I don’t know yet; mamma isn’t[34] well enough to be talked to, and we’ll have to wait till papa comes home. Perhaps papa won’t think you are too young to drive Whiz just out to Rosewood. It isn’t like going to Parnassus, ten miles; you know he didn’t allow that.”

“Pretty well too if a fellow fourteen years old can’t be trusted with that old rack-o-bones,” said the youth scornfully, remembering that Preston at his age had driven Whiz; but then Preston and Fred were different boys.

“Well, I’ll be the one to ask him,” said Mary. “Shouldn’t you think the moon would make a great difference? I should.”

It was while Dr. Gray was carving the roast beef at dinner that Mary came out desperately with the spelling-school question. He seemed to be thinking of something else at first, but when brought to understand[35] what she meant, he said Miss Pike was a sensible woman, and he approved of her, and Mary and Fred “might go and spell the whole school down if they could.”

This was beyond all expectation. Fred looked gratified, and Mary, slipping from her chair, sprang to her father and gave him a sudden embrace, which interfered with his carving and almost drove the knife through the platter.

All the afternoon her mind was much agitated. What dress should she wear? Did Ninny think mother would object to the best bonnet? And oh, she ought to be spelling every moment! Wouldn’t grandma please ask her all the hard words she could possibly think of?

Grandma gave out a black list,—eleemosynary, phthisic, poniard, and the like,—and though Mary sometimes tripped, she did[36] admirably well. Logomachy, anagrams, and other spelling games were popular in the Gray family, and all the children were good spellers. Dr. Gray said, “They tell us that silent letters are to be dropped out of our language, and then the words will all look as they sound; but this has not been done yet, and meanwhile it is well to know how to spell words as they are printed now.”

Julia was in her mother’s room, and Mary was left again with the care of the children; but in her present distraction she quite forgot Ethel, and the child, left to her own devices, managed to get the lamp-scissors and cut off her hair. The zigzag notches, bristling up in all directions, were a droll sight.

“Oh, you little mischief,” cried Mary, angry, yet unable to help laughing. “This all comes of my reading you the story of the[37] ‘Nine Little Goslings’ yesterday. Tell me, was that what made you think of it?”

Ethel nodded her sheared head silently.

“Oh, you dreadful child. When I was trying so hard to interest you! I didn’t want to read to you! And to think you must go and do this! What do people mean by calling you good? I never cut off my hair, but nobody ever called me good!”

Mary was seized again with laughter, but, recovering, added sternly:—

“It’s very hard that I can’t shut you in the closet, but you’ll get there fast enough! Yes, I shall report you, and into the closet you’ll go, Miss Snippet. Oh, you needn’t cry; you’re the worst-looking creature in town, but the blame always falls on me! Just for those ‘Nine Little Goslings.’ And here was I working so hard to get ready for spelling-school and—”

The jingle of sleigh-bells put a sudden stop to this eloquence. Ethel wiped her eyes and stole to the window without speaking. She was usually dumb under reproof, and perhaps it was her very silence which encouraged Mary to deliver “sermonettes,” though I fear these sermonettes hardened instead of softening little Ethel’s heart. The young preacher was smiling enough, however, when she went out to enter the sleigh; and Julia, who tucked her in, looked as if she were trying her best not to be proud of her bright young sister. Mary felt very well pleased with herself in her new cloak and beaver hat, with its jaunty feather; but she was not quite satisfied with cousin Fred.

“He can’t drive half as well as Preston; and, worse than that, he doesn’t know how to spell,” thought she, as they drove on in[39] time to the merry music of the bells. They had gone about half a mile, and Fred had used the whip several times with a lordly flourish, always to the great displeasure of Whiz, when they were suddenly brought to a pause by a loud voice calling out,—

“Stop! Hilloa, boy, stop!”

To say that they were both very much frightened would be no more than the truth. Mary’s first thought was the foolish one, “Oh, can it be a highway robber?” while Fred wondered if anything was amiss with the harness. It might be wrong side upward for aught he knew.

But they were both alarmed without cause. As soon as Fred could rein in his angry steed, it appeared that the owner of the voice was only Mary’s old friend and former teacher, Mr. Harrison Fling, and all he wished to say was,—

“Well, Miss Mary and Master Fred, are you going to spelling-school?”

“Yes, sir,” said Fred, touching his cap; while Mary hoped nothing had happened to the spelling-school to prevent their going.

“And may I ride with you?” asked the young man, with a persuasive bow and smile.

“Yes, sir, if you like,” replied Fred, rather relieved to find it was no worse, though certainly not pleased.

“I’ll drive, of course,” said Mr. Fling serenely, seating himself, and taking Mary in his lap. “Master Fred, your aunt will thank me for happening along just as I did, for you were going at breakneck speed. You would have been spilled out at the next corner.”

Fred’s brows were knitted fiercely under his cap. Was it possible that Mr. Fling was regarded as a gentleman?

“Miss Flaxie,” pursued the interloper, “I hope you’re as glad to see me again as I am to see you. Don’t you feel safer now I’ve taken the reins?”

Mary did not know what reply to make. She was not glad to see him, yet she did feel safer to have him drive. She laughed a little, and the laugh grated unpleasantly on Fred’s ears. This was the first time he had ever taken his young cousin to ride, and he thought it would be the last.

Mr. Fling talked all the way to Miss Pike’s school-house, apparently not minding in the least that nobody answered him. “Now, children,” said he, lifting Mary out, and planting her upon the door-stone before Fred could offer his hand, “now, children, with your permission, I’ll drive a little farther. I’d like to drop in on a few of my old friends in this neighborhood. Give my[42] very best regards to Miss Pike, and tell her I hope to be back in season to hear a little of the spelling.”

“With your permission,” indeed! Fred was incensed. If Mr. Fling had been a person of his own age, he would have said to him, and very properly, too, “I have no right to lend Dr. Gray’s horse, and you have no right to ask me for him.” But as Mr. Fling was at least a dozen years older than himself, such a speech would have been impertinent; and Fred could only look as forbidding as possible, and preserve a total silence, while Mr. Fling caught up the reins again, and was off and away without further ceremony.

“Isn’t he a funny man?” said Mary. “Funny” was not the word Fred would have used.

The spelling-school had not yet begun, but Fanny Townsend and her brother Jack had already arrived, and so had Mr. Garland, and his nephew, Mr. Porter. Miss Pike expressed pleasure at seeing them all, and stood at the desk some time with her arm around Mary’s waist, chatting about “old times” at Laurel Grove, at Hilltop, and at Washington. Mary was feeling of late that there were many old times in her life, and that she had lived a long while. She had been quite a traveller, had seen and known a variety of people, but nobody—outside her[44] own family—that is, no grown person,—was so dear to her as this excellent young lady, who was known among strangers as “the homely Miss Pike.” Mary had attended her school at Hilltop with Milly Allen, and afterward Miss Pike had been a governess in Dr. Gray’s family, and still later had spent a winter with the Grays at Washington. She had a decided fancy for Mary; and in return the little girl always called Miss Pike her “favorite friend.” It is only to be wished that every little girl had just such a “favorite friend.”

But it was now time for the exercises to begin. At a tap of the bell everybody was seated. The scholars were nearly all older than Mary, she and Fanny being perhaps the youngest ones there.

“This is an old-fashioned spelling-match,” explained Miss Pike to her visitors, “and we[45] will now announce the names of the two ‘captains,’ Grace Mallon and James Hunnicut. They will take their places.”

Upon this James Hunnicut, a large, intelligent-looking boy of fifteen, walked to one side of the room and stood against the wall, and Grace Mallon, a sensible young girl of fourteen, walked to the other side of the room, and took her place exactly opposite James. They both looked very earnest and alive.

Grace had the first choice; next James; and so on for some minutes. There was breathless interest in it, for, as the best spellers would naturally be chosen first, the whole school sat waiting and hoping. The house was so still that one heard scarcely a sound except the names spoken by the two captains, and the brisk footsteps of the youths and maidens crossing the room, as[46] they were called, now to Grace’s side, now to James’s, there to stand like two rows of soldiers on drill.

Miss Pike could not but observe the sparkle of satisfaction in some faces, and the gloom of disappointment in others; and she rejoiced with the good spellers and grieved with the poor ones, like the dear, kind woman she was.

Out of courtesy, Mary Gray and Fanny Townsend were chosen among the first. James Hunnicut supposed it would be ungallant to neglect visitors, though he did wince a little as he called Mary Gray’s name, thinking, “What do I want of a baby like that? Of course she’ll miss every word.”

Mary answered James’s call with a throbbing heart, proud, delighted, yet afraid. Next Grace Mallon called Fred Allen, and thought, when he walked over to her side[47] with his well-bred air, that she had secured a prize. How could she suspect that a distinguished-looking lad like that was not a “natural speller,” and did not always do as well as he knew, on account of his habit of speaking before he thought? In fact, he missed the very first word, exactly, making the first syllable eggs in his ruinous haste. Of course he knew better, but no allowance was made for mistakes, and like a flash the word was passed across the room to Mary, who spelled it correctly.

Fred felt disgraced, lost all confidence, and, if he had dared, would have asked to be excused from duty. Captain Grace would have excused him gladly, but such a thing was never heard of; he must stand at his post, and blunder all the evening.

It was the custom, when a word was missed on one side and corrected on the[48] other, for the successful captain to swell his own numbers by “choosing off” one from the enemy’s ranks. Captain James now “chose off” one of Captain Grace’s best soldiers, and the game went on.

Next time it was one of Captain James’s men—Fanny Townsend—who blundered, and it was Captain Grace’s turn to choose off.

For some time the numbers were about even; but as Fred Allen invariably missed, and there were Jack Townsend and other poor spellers below him to keep him company, Captain James began to have a decided advantage. He kept choosing off again and again,—Mary Gray, among the rest,—while Captain Grace bit her lips in silence.

But the moment she had it in her power she called a name in a ringing voice, and it was “Mary Gray.” Mary had spelled all her[49] words promptly,—they had usually been hard ones, too,—and her blue eyes danced as she tripped across the room in answer to the call. Was there a ray of triumph in her glance as it fell on cousin Fred, who was propping his head against the wall, trying to look easy and unconcerned? Fred, who was so much older than herself, and ciphering at the very end of the arithmetic? Fred, who had always looked down on little Flaxie as rather light-minded?

There he stood, and there he was likely to stand, and Jack Townsend, too, while the favorite spellers with ill-concealed satisfaction were walking back and forth conquering and to conquer.

Mary Gray was called for as often as the oldest scholar in the room, and, as she flitted from east to west, her head grew as light with vanity as the “blowball” of a dandelion.[50] She threw it back airily, and smiled in a superior way when poor Fred missed a word, as if she would like to say to the scholars, “I came here with that dunce, it’s true, but please don’t blame me because he can’t spell.”

“That’s a remarkably bright, pretty little girl, but I fancy she wouldn’t toss her head so if there was much in it,” whispered Mr. Garland’s nephew to Miss Pike, while Mr. Garland was putting out the words.

Miss Pike had been pained by Mary’s silly behavior, but replied:—

“You are wrong, quite wrong, Mr. Porter, she is a dear little girl and has plenty of sense.”

It was positively gratifying to the good lady afterwards to hear Mary mis-spell the word pillory, for the mortification humbled her, and from that moment there was no more tossing of curls.

When the time was up, Captain James’s side had conquered most victoriously, numbering twice as many as the other side. The two captains bowed to each other and the game was over. Then Fred Allen, Fanny Townsend, and all the other wallflowers were allowed at last to move. It was time to go home.

The girls and boys, all shawled and hooded and coated and capped, went toward the door, chatting and laughing.

James Hunnicut said to Grace Mallon, “Beg your pardon; I didn’t mean to take all your men.”

“Oh,” returned Grace, undaunted, “I had men enough left, and dare say I should have got every one of yours away from you if we’d only played half an hour longer.”

“Ah, you would, would you? Well, we’ll[52] try it again and see. Isn’t that little girl of Dr. Gray’s a daisy?”

“Not quite equal to the Allen boy; I admire him,” returned Grace in an undertone; but Fred heard and buttoned his overcoat above a swelling heart.

“Good night, we’re all so glad you came,” said Miss Pike, shaking hands warmly with him and Mary. Then off she went, and half the school followed, walking and riding by twos and threes and fours.

But where, oh where, in the name of all the spelling-schools, was Fred’s horse? There wasn’t the shadow of him to be seen. Where was Fred’s sleigh? There was not so much as the tip of a runner in sight. Where was Mr. Fling? Gone to Canada, perhaps, the smooth-faced deceitful wretch!

Fred would “have a sheriff after him,” so[53] he assured cousin Flaxie, and that immediately.

Mary stamped her little low-heeled boots to keep her feet warm, and highly approved of the plan.

“Oh yes, Fred, do call a sheriff; I’m perfectly willing;” and the situation seemed delightfully tragic, till somebody laughed, and then it occurred to her that sheriffs, whatever they may be, do not grow on bushes or in snow-banks. And, of course, Mr. Fling had not gone to Canada, Fred knew that well enough; he had only “dropped in” at somebody’s house and forgotten to come out.

“The people, wherever he is, ought to send him home,” said James Hunnicut sympathetically.

“That’s so,” assented two or three others. “It’s abominable to go ’round calling with a borrowed horse and sleigh.”

So much pity was galling to both Mary and Fred, making them feel like young children, who ought not to have been trusted without a driver. Why wouldn’t everybody go away and leave them. The situation would surely be less embarrassing if they faced it alone.

Fred was angry and undignified. He had had as much as he could bear all the evening, and this was a straw too much. Mary, on the other hand, had enjoyed an unusual triumph; but how her feet did ache with cold! The blood had left them hours ago to light a blazing fire in her head; and now to stand on that icy door-stone was torture!

“I know I shall freeze, but I’ll bear it,” thought she, taking gay little waltzing steps. “How they do admire me, and it would spoil it all to cry. Why, all the great spelling I[55] could do in a year wouldn’t make up for one cry.”

Just as she had got as far as to remember that she had heard of a man whose feet “froze and fell off,” Grace Mallon asked when her brother Phil would have a vacation? She had shut her teeth together firmly, but being obliged to answer this question, her voice, to her dire surprise and confusion, came forth in a sob! Not one articulate word could she speak; and there was Captain James Hunnicut looking straight at her! Keener mortification the poor child had seldom known. Following so closely, too, upon her evening’s triumph! But at that moment Mr. Garland, who was about driving off with his nephew, stopped his horse and said: “This is too bad! Here, Miss Flaxie, here’s a chance for you to ride with us. We can make room for her, can’t we[56] Stephen? But as for you, Master Fred, I see no other way but you must wait for your horse.”

Mary, utterly humbled, sprang with gratitude into Mr. Garland’s sleigh, without trusting herself to look back.

And Fred did “wait,” with a heart swelling as big as a foot-ball, and saw his cousin bestowed between the two gentlemen, who smiled on him patronizingly, as upon a boy of four in pinafores.

This was hard. And when Mr. Fling appeared at last, laughing heartlessly, and drove the half-frozen boy part of the way home, leaving him at the hotel, the most convenient point for himself, and advising him to take ginger-tea and go to bed,—this oh, this, was harder yet!

But it was Mrs. Gray who suffered most from this little fiasco. Before the children[57] returned she was flushed and nervous, and Dr. Gray blamed himself for having allowed them to go.

“I’m thankful, my daughter, that you’ve got here alive,” said she, sending for Mary to come to her chamber; “Whiz is a fiery fellow, and Fred isn’t a good driver.”

“Was it as delightful as you expected, Mary? And did you spell them all down?” asked her father.

“Yes, sir, it was delightful; and I spelled ever so many hard words, and only missed one; but Fred spells shockingly,” replied Mary, taking up a vial from the stand and putting it down again.

“So, on the whole, I see you didn’t quite enjoy it,” said Mrs. Gray, rather puzzled by Flaxie’s disconsolate look.

“Not quite, mamma; don’t you think Mr. Fling was very impolite? And oh, I must[58] warm my feet, they are nearly frozen,” said Mary, questioning within herself why it was that, whenever she had a signal triumph, something was almost sure to happen that “spoiled it all.”

The spelling-school, with its triumphs and chagrins, had partially faded from Mary’s memory, to become one of her “old times;” for winter had gone, and it was now the very last evening of March.

You may not care to hear how the wind blew, and really it has nothing to do with our story, only it happened to be blowing violently. Tea was over, and everybody had left the dining-room but Mary and cousin Fred. Mary had just parted the curtains to look out, as people always do on a windy night, when Fred startled her by saying, in a whisper, “Flaxie, come here.”

She dropped the curtain hastily, and crossed the room. What could Fred be wanting of her, and why should he whisper when they two were alone, and the wind outside was making such a noise?

“Put your ear down close to my mouth, Flaxie. You mustn’t tell anybody, now remember.”

“Why not, Fred? It isn’t best to make promises beforehand. Perhaps I ought to tell.”

“Ought to tell? I like that! Then I’ll keep it to myself, that’s all.”

“Now, Fred, I didn’t say I would tell. And, if it’s something perfectly right and proper, I won’t tell, of course.”

“Oh, it’s right and proper enough. Do you promise? Yes or no?”

“Yes, then,” said Flaxie, too anxious for Fred’s confidence, and too much honored[61] by it to refuse, though she knew from past experience that he frequently held peculiar views as to “propriety.”

“Here, see this,” said he, taking a smooth block of wood from his pocket and whispering a word of explanation. “Won’t it be larks?”

She drew back with a nervous laugh. “Why, Fred!”

“And I didn’t know but you’d like to go with me, Flaxie, just for company.”

“But do you think it’s exactly proper? He’s a minister, you know.”

“Why that’s the very fun of it,—just because he is a minister! It’s the biggest thing that’ll be done to-morrow, see if it isn’t?”

Mary looked doubtful.

“I was a goose to tell you, though, Flaxie; I might have known girls always make a fuss.”

“Oh, it isn’t because I’m a girl, Fred! Girls like fun as well as anybody, only girls have more——.” She did not know whether to say “delicacy” or “discretion,” but decided that either word would give offence; “girls are different.”

“Then you won’t go with me? No matter. I believe, after all, I’d rather have one of the boys.”

“Yes, oh yes, I will go with you; I’d like to go,” exclaimed Mary, desperately, throwing discretion to the winds.

“Agreed, then,—to-morrow morning on the way to school. And now mind, Flaxie, don’t put this down in your journal to-night, for that would let it all out.”

“Why, nobody ever looks at my journal! It would be dishonest.—Why, Fred,” in sudden alarm, “did you ever look at my journal?”

“Poh! what do I care for your old scribblings?” The boy’s manners had been falling to decay all winter for lack of his mother’s constant “line upon line.” “Only your journal is always ’round, and you’d better be careful, that’s all.”

Next morning it rained, and Mary walked to school with Fred under the gloom of a big umbrella, Phil having been sent on in advance.

“Pretty weather for April Fools,” remarked Fred, carefully guarding under his arm a neat little package containing a block of wood, with a card, on which were the words, simple but significant, “April Fool.”

Arriving at Rev. Mr. Lee’s door-yard, he walked up the narrow gravel-path with Flaxie beside him, “just for company.”

“Now don’t laugh and spoil it,” said he. And, to solemnize his own face, he tried to[64] think of the horrible time last summer, when he and his brother John went for pond-lilies, and were upset and nearly drowned. Mary looked as if she were thinking of an accident still worse, her face drawn to remarkable length, and her mouth dolefully puckered.

“You don’t suppose Mr. Lee will come himself, do you?” whispered Fred, ringing the door-bell very gently.

“Oh Fred, let’s go away. Just think if he should put you in a sermon? He put somebody in once for stealing watermelons. He didn’t say the name right out, but——”

Two early dandelions by the front window seemed bubbling over with merriment and curiosity; but before they or Fred had learned who stole the watermelons, Fred stopped his cousin by saying contemptuously, “When a man gets nicely fooled he won’t put that in a sermon, you’d better[65] believe.” And then, gathering courage, he rang louder.

Mary was deliberating whether to run or not, when the housemaid appeared.

“Will you give this to Mr. Lee? Very important,” said Fred, handing her the dainty little parcel.

She looked at it, she seemed to look through it; a merry glint came into her eyes.

“I was afraid somebody was dead,” said she. “You rung so loud, and you looked so terrible solemn, both of you.”

“Solemn?” echoed Fred; and then it was he, not Mary, who broke down and smiled.

“Mr. Lee’s gone to a funeril,” continued Hannah, looking through and through the parcel again; “but I’ll give it to him when he comes home, and tell him who brought it.”

Did Fred wish her to tell him? He began to doubt it.

“Come, Flaxie, we must go.”

“Fred,” said the little girl, as they hurried out of the gate, “I can’t help thinking; shan’t we feel sorry next Sunday?”

“Nonsense!” returned her cousin. He had already thought about Sunday, and fancied himself looking up to the pulpit to meet Mr. Lee’s eye. Had he been quite respectful to that learned and excellent man?

“Nonsense! ministers are no better than other folks!”

It was too late to repent; but he wished now he had waited till afternoon and thought of all the possible consequences. Perhaps the fun wouldn’t pay. These doubts, however, he did not mention to the boys at school, but told them he had made “a splendid fool” of the minister.

That evening, as he and Mary stood by the carriage-way gate, and he was opening it for Dr. Gray to drive into the yard, who should be passing on the other side of the street, but Mr. Lee.

“How do you do, Dr. Gray,” said he; and came over to do a trivial errand, which Fred fancied must have been made up for the occasion; it was something about a book which he wished to borrow some time, not now. Then, turning to guilty Fred, who had not dared slip away,—

“Good evening, Master Fred,” with extreme politeness; “I was very sorry not to be at home this morning when you left your card.”

Your card! Those were his words.

“My card! Does he think I signed myself April Fool? My goodness, so I did! People always put their own names on their[68] visiting-cards, sure enough! It’s I that am the April Fool, and nobody else,” thought the outwitted boy, not venturing to look up.

A blush mounted to Mary’s forehead, and she too looked at the ground.

“Pray call again, Master Fred,” said Mr. Lee; and his manner was as respectful as if Fred had been at least a supreme judge.

“What’s all this?” asked the doctor sternly as the clergyman walked away.

“’Twas a little kind of a—a joke, you know, sir, for fun. I didn’t mean anything. I like Mr Lee first rate,” stammered Fred, scanning his boots, as if to decide whether they were big enough for him to crawl into and hide.

Dr. Gray never needed to be told more than half a story.

“Oh, I see! You’ve made an April Fool of yourself. Ha, ha! Mr. Lee is too sharp[69] for you, is he? And so, Mary, you went with Fred?”

The doctor looked grave. It was not easy to let this pass. “Wait here, both of you, till I come back,” said he, driving into the stable.

“This is a great go,” thought Fred. “Hope the boys won’t hear of it.”

“Fred,” said Dr. Gray, returning,—and he spoke with displeasure,—“I am disappointed in you. And in you too, Mary.”

“Oh, papa,” wailed a little voice from under Mary’s hat. Her head was bowed, and her tears were falling.

“I was the one that thought of it; I was the one that asked her to go,” spoke up Fred, all the manliness in him stirred by his cousin’s tears.

“No doubt you were; and I’m glad to hear you acknowledge it,” said Dr. Gray,[70] resting his hand on his nephew’s shoulder. “But Mary knew better than to be led away by you. My daughter, jests of this sort may be tolerated in your own family or among your schoolmates; but do you think they are suitable to be played upon ministers?”

“No, sir,” sobbed Mary.

“Well, then, let this be a lesson to you.” This was a favorite speech with the doctor. “Kiss me, my child; and now run into the house. I shall never refer to this matter again, and it is not necessary to mention it to your mother. But Fred,” he added, as Mary swiftly escaped, “do you think your conduct has been gentlemanly and courteous? Ought you to have taken this liberty with a comparative stranger,—a person, too, of Mr. Lee’s high character?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you think your mother would be pleased to hear of it?”

“I know she wouldn’t,” admitted Fred frankly.

Dr. Gray’s countenance softened.

“I don’t like to be harsh with you, for you meant no impertinence; still, if I am to treat you as my own child, as your parents desire, I believe I shall have to bid you ask Mr. Lee’s pardon. What say you to that? It’s the way I should treat Preston.”

“All right,” replied Fred sadly.

Next morning saw the lad, cap in hand, knocking at the door of the minister’s study. Mary had half-offered to go with him, but he had scorned to accept the sacrifice.

“Come in,” said Mr. Lee, opening the door.

Fred advanced one step into the room. There was an awful pause, during which those very dandelions of yesterday winked at him from a silver vase, and his well-pondered speech began to grow hazy.

“My uncle sent me to apologize,” he faltered forth. “I didn’t mean to be disrespectful to a—to a minister. For I think—of course I think—that ministers——”

Here a certain twinkle in Mr. Lee’s eye distracted Fred, and his speech flew right out of the window. “For I don’t think,” added he, in wild haste, “that ministers are any better than other folks.”

It was just like Fred. He had meant to say something entirely opposite to this; but the “imp of the perverse” was apt to seize his tongue. Oh, dear, he had finished the business now!

“I agree with you, my boy; ministers aren’t any better than other folks, certainly,” said Mr. Lee, laughing outright in the most genial way.

“Oh, that wasn’t what I meant, sir. Please don’t think I meant to say that,”[73] pleaded Fred, feeling himself more than ever the most foolish of April fools.

But the good-natured clergyman drew him into the room. “Come, now,” said he, still laughing, though not sarcastically at all, just merrily, “let me have the call I missed yesterday. Your cousin Preston is one of my best friends, but I think you’ve never entered my study before.”

It was a cosy, sunny room, and, beside books, held a large cabinet, and a green plant-stand, blooming with flowers. Fred seated himself on the edge of a chair, ready for instant departure; but Mr. Lee chatted most agreeably, telling interesting stories, and inquiring about Hilltop people, till he forgot his embarrassment, and was soon asking questions in regard to the different objects in the cabinet.

What was that whitish, buff-colored stuff?[74] Coquina? Oh! And people built houses of it? Possible? Was it really made of shells? How strange!—Well, that tarantula’s nest was a queer concern! Why, it shut down like a trap-door exactly. Looked as if it had a hinge, and a carpenter made it.—Was that an eagle’s claw?—Oh, and that? A rattlesnake’s rattle?—Was this a scorpion?—And so on.

It was a varied collection, and Mr. Lee seemed to have nothing to do that morning but to exhibit it. Not another word about the April Fool; but Fred felt that he was forgiven, or, rather, that no forgiveness was needed, as no offence had been taken.

“I tell you, Flaxie,” confided he to his cousin afterward, “I never liked Mr. Lee half so well; never dreamed he was so bright and sharp. He likes fun as well as we boys. Only somehow—Well, I wouldn’t do it[75] again; it was foolish. See here, Flaxie, have you put this in your journal? Well, don’t you now! If the boys should find out—”

“What do you mean about my journal?” returned Mary, drawing up her mouth like the silk “work-pocket,” to mark her displeasure. “Anybody’d think my journal was a newspaper.”

Fred smiled wisely.

The journal was a pretty little red book, which lay sometimes on the piano, sometimes on the centre-table, and was often opened innocently enough by callers. If it had been the simple, matter-of-fact little book that it ought to have been, the reading of it would have done no harm. But Mary had a habit of recording her emotions, also her opinions of her friends,—a bad habit, which she did not break off till it had nearly brought her into trouble.

“What does Fred Allen mean by calling me ‘Miss Fanny dear, with mouth stretched[77] from ear to ear’?” asked Fanny Townsend, indignantly.

“How do you know he did?”

“Saw it in your journal. And you put a period after ‘Miss’! Needn’t accuse me of laughing, Flaxie Frizzle, when I happen to know that my mother considers you a great giggler, and dreads to have you come to our house.”

“Does she? Then I’ll stay away! And if I did put a period after ‘Miss’ it was a mistake. But I’ve no respect for people that read other people’s private journals!”

“Hope you don’t call that private. Why, I thought ’twas a Sabbath-school book, or I wouldn’t have touched it.” And whether she would or not, Fanny was obliged to laugh; so the breach was healed for the time. But after this Mary began a new journal, which she conducted on different[78] principles, trying moreover to keep it in its proper place in her writing-desk.

There were secret signs and mysterious allusions in this new journal, however, the letters “C. C.” recurring again and again in all sorts of places, without any apparent meaning or connection. She evidently enjoyed scribbling them, and no harm was done, since nobody but “we girls” knew what they meant. “C. C.” was a precious secret, which we may pry into for ourselves by-and-by.

Mary was now in her thirteenth year, and though she still enjoyed hanging May-baskets, driving hoops, skipping the rope, and even playing dolls, her growing mind was never idle. She enjoyed her lessons at school, for she memorized with ease; she liked to draw; but sitting at the piano was a weariness; and she considered it a trial that,[79] in addition to her own practising, she should be expected to teach and superintend Ethel. She was strict with her little pupil, and found frequent occasion for sermonettes, but Ethel got on famously, and Mary received and deserved high praise as teacher.

She missed her cousin Fred when he went home at last, not to return, but she told Lady Fotheringay (Blanche Jones) in confidence that she “could improve her mind better when he was gone.” Moreover, Preston would soon be home for his summer vacation.

She was beginning to question what she was made for. Something grand and wonderful, no doubt; something much better than studying, reading, sewing, and doing errands. There were times when this favored child of fortune even said to herself that life was hard, and that her mother was[80] over-strict in requiring her to mend her clothes and do a stint of some sort of sewing on Saturdays. Wasn’t she old enough yet to have outgrown stints?

“Why can’t pillow-cases be hemmed by machine?” complained she to Ethel. “And there you are,—almost six years old, with not a thing to do! I can tell you I used to sew patchwork at your age by the yard! C. C. I keep saying that over to comfort myself, Ethel, but you don’t know what it stands for. Oh no, not chocolate candy; better than that!—Wish I lived at the south, where colored servants do everything. There’s Grandma Hyde now; if we had her black Venus, and her black Mary, and her yellow Thomas, I shouldn’t have to dust parlors and run of errands! Mamma is always talking to me about being useful. Little girls are never talked to in that way; it’s we older[81] girls who have to bear all the brunt. It tires me to death to sew, sew, sew! Now it’s such fun to run in the woods. Mr. Lee says we ought to admire nature, and I’m going after flag-root this afternoon instead of mending my stockings—I think it’s my duty!”

As Mary rattled on in this way, little Ethel listened most attentively. Her sister Flaxie stood as a pattern to her of all the virtues,—ah, if Flaxie had but known it!—and she looked forward to the time when she should be exactly like her, with just such curls, and just that superior way of lecturing little people. It was not worth while to be any better than Flaxie. If Flaxie objected to sewing and mending, Ethel would object to it also.

“If my mamma ever makes me sit on a chair to sew patchwork, I’ll go South! If[82] she makes me mend stockings, I’ll go in the woods! I won’t be useful if Flaxie isn’t; no indeedy!”

Thus while Flaxie’s sermonettes were forgotten, her chance words and her example took deep hold of the little one’s mind.

Everybody said Mary was growing up a sweet girl, more “lovesome” and womanly than had once been expected. In truth Mary thought so herself. Plenty of well-meaning but injudicious people had told her she was pretty; and she knew that Mrs. Lee liked to look at her face because it was so “expressive,” and Mrs. Patten because it was so “thoughtful,” and somebody else because it was so “intelligent.” Ethel had a figure like a roly-poly pudding; but Mary was tall and slight, and even Mrs. Prim admitted that she was “graceful.”

One Sunday morning early in May she sat[83] in church, apparently paying strict attention to the sermon, but really thinking.

“I dare say, now, Mrs. Townsend is looking at me, and wishing Fanny were more like me. Nobody else of my age sits as still as I do, except Sadie Stockwell, and she has a stiff spine. There’s Major Patten, I remember he said once to father, ‘Dr. Gray, your second girl is a child to be proud of.’ I know he did, for I was coming into the room and heard him.”

Directly after morning services came Sunday school, and Mary was in Mrs. Lee’s class. Mrs. Lee was an enthusiastic young woman, fond of all her scholars, but it was easy to see that Mary was her prime favorite. Mrs. Gray’s class of boys—Phil being the youngest—sat in the next seat. The lesson to-day was short, and after recitation Mrs. Lee showed her own class and Mrs. Gray’s[84] some pictures which her uncle had brought her from China.

“What is that queer thing?” said Fanny, as she and Mary touched bonnets over one of the pictures.

“That is called a baby-tower. My uncle says it is a good representation of the dreadful place they drop girl-babies into sometimes. You know girls are lightly esteemed in heathen countries.”

“Drop girl-babies into it?” asked Blanche Jones. “Doesn’t it hurt them?”

“Not much, I believe; but it kills them.”

“Oh, Mrs. Lee!” It was Mary who spoke, in tones of horror.

“The tower is half full of lime, and the lime stops their breath. So I presume they hardly suffer at all.”

Mary’s eyes were full of tears, and she sprang up eagerly, exclaiming,—

“Oh, Mrs. Lee! Oh, mamma, did you hear that? I declare, it’s too bad! Can’t the missionaries stop their killing babies so?”

“You sweet child,” said Mrs. Lee.

But Mrs. Gray only said,—

“Yes, my daughter, the missionaries are doing their best; but everything can’t be done in a day.”

“But it ought to be done this very minute, mamma.”

Mary’s whole face glowed; and Mrs. Lee, who sat directly in front of her, could not refrain from leaning over the pew and kissing her.

“We ought to bring more money, seems to me,” suggested good, moon-faced Blanche Jones, pressing her fat hands together.

“Yes, a cent every Sunday is too little,” said one of Mrs. Gray’s little boys.

“Yes, a cent is too little,” agreed Fanny Townsend earnestly.

“How thoughtless we’ve been,” said Mary, in high excitement. “For my part, I mean to give those Chinese every cent of my pin-money this month. Do you care if I do, mamma?”

“No; you have my full consent. Only do not make up your mind in a hurry,” replied Mrs. Gray; but her manner was cold in comparison with Mrs. Lee’s cordial hand-shake and “God bless you, my precious girl.”

“I’m a real pet with Mrs. Lee,” thought Mary, her heart throbbing high.

Blanche, Fanny, and the two older girls in the class,—Sadie Patten and Lucy Abbott,—were silent. They knew that Mary’s pin-money amounted to four dollars a month, and though they had thought of doing something themselves, this brilliant offer discouraged them at once: they could not make up their minds to anything so munificent.

Going home that noon, Mary “walked on thorns,” though she tried to be humble. By the next day, her feelings toward the Chinese had undergone a slight chill; and when her mother alluded to Captain Emerson—Mrs. Lee’s uncle—and his pictures, Mary did not care to converse on the subject. She even felt a pang of regret at the recollection of her hasty promise. Those girl-babies were far off now; she could not see them in imagination, as at first. Days passed, and the poor things were fading out of mind, buried deep in the lime of the tower.

“My daughter,” said Mrs. Gray, on Saturday, “let me see your portmonnaie.” It contained three dollars and a half now. Mrs. Gray counted the bills. “Have you any especial use for this money, Mary?”

“I don’t know. Would you buy those stereoscopic views of Rome and the Alps[88] that Mr. Snow said I could choose from different sets?”

Mrs. Gray smiled quietly.

“What good will the views do the babies in China?”

There was a sudden droop of Mary’s head.

“Why, mamma, as true as you live I forgot all about those babies; I really did! You see, mamma, I didn’t stop to think last Sunday. Must I give all my money to Mrs. Lee—three dollars and a half?”

“To Mrs. Lee? I was under the impression that you were to give it to the missionaries to convert the Chinese.”

“Oh, yes, but I said it to Mrs. Lee; the missionaries don’t know anything about it.”

“So it seems,” returned Mrs. Gray dryly; “you said it to Mrs. Lee merely to please her.” Mary’s head sank still lower. “Well,[89] you might ask Mrs. Lee to let you off, my daughter.”

“But, mamma, how it would look to go to her and ask that! I couldn’t!”

“Then you’ll be obliged to give the money,” responded Mrs. Gray unfeelingly. How easily she might have said, “Never mind, Mary, I will see Mrs. Lee and arrange it for you.” And she was usually a thoughtful, obliging mother. Mary pressed the bills together in her hand, spread them out tenderly, gazed at them as if she loved them. It was a large sum, and looked larger through her tears.

“I can’t ask Mrs. Lee to let me off; you know I can’t, mamma. I’d rather lose the money!”

“Lose the money!” So that was the way she regarded it! A strange sort of benevolence surely!

“Take heed, therefore, that ye do not your alms before men to be seen of them; otherwise ye have no reward of your Father which is in heaven.” This was Mr. Lee’s text next day.

“Oh, that means me,” groaned Mary inwardly. “I’ve been seen of Mrs. Lee, and I’ve been seen of Blanche and Fanny and the other girls; and that’s just what I did it for, and not for the people in China! Oh, dear! oh, dear! to think what a humbug I am!”

And now we come to an episode of the highest importance to five young misses of Laurel Grove. General Townsend owned an unoccupied house about two miles from town, at the foot of a steep hill called Old Bluff; and it had occurred to the active mind of Mary Gray that this would be a fine place for “camping out.”

It was April when she hinted this to Fanny Townsend, but it was May before Fanny spoke of it to her father.

“I’m waiting till some time when you come to my house to tea, Dandelina; and[92] we mustn’t get to laughing, now you remember.”

Mary seated herself at the Townsend tea-table one evening with nervous dread; for, next to Mrs. Prim, Mrs. Townsend inspired her with more awe than any other lady in town. When she thought it time for Fanny to speak, she touched her foot under the table, and Fanny began.

“Papa, I have something to say.”

Fanny had the feeling that she was not highly reverenced by her family, on account of her unfortunate habit of giggling; but her face was serious enough now. “Papa, may we girls go down to the farm next summer,—to that house with the roses ’round it,—and camp out? The girls all want to, and we—we’re going to call it Camp Comfort.” (The reader will perceive that this explains the letters “C. C.”) She was sorry next moment[93] that she had spoken, for her mother said, just as she had feared she might, “What will you think of next, Fanny?”

But her father seemed only amused. “Camp out? We girls? How many may ye be? And who? Going to take your servants?”

“You’ll each need a watch-dog,” suggested Fanny’s elder brother, Jack.

“You’ll come home nights, I presume,—servants, watch-dogs and all,” said her father.

“O no, indeed! It wouldn’t be camping out if we came home nights! And nobody has a dog but Fanny, and we shouldn’t want any servants,” cried Mary Gray, whose views of labor seemed to have changed materially.

“We intend to do our own work,” remarked Fanny. Whereupon everybody laughed; and General Townsend asked again who the girls were? “Oh, Flaxie Frizzle and Blanche[94] Jones and I, papa; that makes three, rather young; and then Sadie Patten and Lucy Abbott, they’re rather old; that makes five. Sadie and Lucy will be the mothers,—I mean if you let us go.”

“That ‘if’ is well put in,” said brother Jack.

“But what will you do for a stove?” asked General Townsend, wishing to hear their plans, “there’s none in the house.”

“My mamma has a rusty stove, and our Henry Mann could take it to Old Bluff,” replied Mary.

“But there’s no furniture,—not a chair or a table.”

“They have too many chairs at Major Patten’s and Mr. Jones’s; their houses are running over with chairs.”

“Well, what about dishes?”

“Why, papa,” said Fanny eagerly, “only[95] think what lots of dishes we have, just oceans, all broken to pieces!”

“Ah, shall you eat from broken dishes?” asked Mrs. Townsend coolly. “And perhaps you’ll sleep on the floor?”

“O no, Mrs. Townsend, our house is full of beds! Mamma has some of them put in the stable, and Blanche Jones’s house is full of beds, and they have to keep some of them in the attic. Everybody has everything; we’ve talked it all over. And there’s our big express wagon, and our Henry Mann to drive.”

Mary paused for breath.

“Yes, papa, Dr. Gray’s express wagon is very large; and we have a push-cart, you know. So can’t we go?” coaxed Fanny, true to first principles.

“What have I to do about it, little Miss Townsend? It seems you have already made[96] your plans and invited your guests. How happened you to think to ask my permission for the rent of the house.”

“Finish your supper, Frances, and do not sit there with your bread in the air,” said Mrs. Townsend in a decided tone. “You forget that I am to be consulted as well as your father. And that’s not all. I’ve no idea that Dr. Gray, or Major Patten, or Mr. Jones, or Mrs. Abbott will consent to this camping out, as you call it; so you must not set your hearts on it, you and Flaxie.”

But it chanced that every one of the parents did consent at last; and one morning in the latter part of June you might have seen some very busy girls loading a push-cart and an express wagon, with the help of their brothers and Henry Mann, while Fanny laughed almost continually, and Mary Gray exclaimed at intervals,—

“O won’t it be a state of bliss?”

There were four bedsteads, eight chairs, one old sofa, one table, one rusty stove, a variety of old dishes,—not broken ones,—beside a vast amount of rubbish, which the mothers thought quite useless, but which the daughters assured them would be “just the thing for our charades.”

“I’m not going to Old Bluff to assist in such performances as charades, so you may just count me out,” said Preston, who was to take turns with Bert Abbott in being a nightly guest at Camp Comfort; since the parents would not consent that the girls should spend one night there alone.

“As if boys were the least protection,” said Lucy Abbott, Preston’s cousin.

“Still they may be useful in getting up games,” returned Sadie Patten hopefully. “And Jack Townsend’s cornet is charming.”

“So it is; it goes so well with your harmonica. And we’ll make the boys stir the ice cream,” said Lucy, the head housekeeper.

There was an ice-house connected with their cottage, and ice cream was to be permitted on Sundays, and lemonade at pleasure.

“But where are the lemons?” said Mary, flying about in everybody’s way.

“Oh, we shall buy fresh lemons every morning of our grocer who comes to our door,” said Lucy grandly. “What I want to know is, if my hammock was packed?—Children, did you see three hammocks in that push-cart?—Boys, I hope you’ll hang up those hammocks before we get there! Don’t go racing now and spilling out things!—There, I don’t believe anybody thought to put in that spider,” added she anxiously, as the five girls had bidden good-by to their[99] families in the cool of the morning, and were walking in a gay procession toward their house in the country.

Old Bluff was a steep, though not very high mountain on the Canada side, and if it is not gone, it stands there yet, hanging defiantly over the blue brook called the river Dee, and throwing its huge shadow from shore to shore.

Old Bluff is a stern, bareheaded peak, and few are the flowers that dare show their faces near it. It is chiefly the hardy wintergreen and disconsolate little sprigs of pine and spruce which huddle together along its sides.

At the foot of this famous bluff, on the New York side, stood General Townsend’s old-fashioned farm-house, a story and a half[100] high, with a white picket fence around it, and a red barn at one side. The house many years ago had been white; and the panes of glass in the windows were not only very small, but weather-stained and streaked with rainbow hues. London Pride or “Bouncing Bet” grew near the broad front door-stone, together with a few bunches of southernwood, which Dr. Gray thought had a finer odor than any geranium. The front yard was grassy, and the fence lined with roses of various sorts.

It was the first summer for years that this pleasant old place had been vacant, and now it might be applied for any day; but meanwhile the five girls, called “the quintette,” and the three attendant cavaliers, called “the trio,” were welcome to rusticate in it, and call it a “camp” if they chose.

After the furniture was set up, and there[101] had been a reasonable amount of play at hide and seek in the barn, and the first supper had been eaten—the tablecloth proving to be too small for the table—Mary went to one of the front “rainbow-windows” to watch for Preston.

“I mean to be a true woman.”

This was what she usually said to herself when resolved not to cry. But there was something lonesome in the thought of going to bed without kissing her mother.

“Nobody else feels as I do, and I wouldn’t mention it for anything; but I’d give one quarter of my pin money—one whole dollar—to see mamma and Ethel.”

She had supposed that in camping out all care would be left behind. Her mother had excused her from lessons and sewing, and she had looked for “a state of bliss;” but it is forever true—and Mary was beginning to[102] find it so—that wherever we are, there is “something still to do and bear.”

Homesickness was a constitutional weakness with Mary, but she disdained the cowardice of running home; she would be a “true woman,” and crack walnuts to please Lucy.

“Well, this is a hard-working family,” said Preston, arriving presently in state on his bicycle, as Lucy and Sadie were engaged in putting the supper dishes in the kitchen cupboard.

“Yes, Mr. Gray; and we allow no idlers here. Please may I ask what ails our window shades, sir?”

The poor old green-cloth curtains were tearing away from the gentle clasp of Sadie Patten’s tack-nails, and leaning over from the tops of the windows as if already tired of the sun and wanting a little rest.

“Well, let’s see your hammer.”

“No, I’m using it, I’m a young lady now and do as I please,” cried Mary, springing up from the kitchen hearth, and scattering her walnuts broadcast, “catch me if you can.”

“Is that so? Well, then, now for a race from here to the sweet-apple tree. One, two, three, begin!” And Preston started off at the top of his speed, Mary just before him, her face aglow, her hair streaming in the wind. As she skimmed over the ground, shouting and laughing, she seemed for all the world like a little girl, and not in the least like a young lady. She was soon caught and obliged to surrender the hammer, whereupon Preston nailed the curtains neatly, and went whistling about the house, giving finishing touches here and there to the rickety furniture.

“O thank you. You’ve been a great help. Now, in return, you shall have a spring-bed[104] to sleep on, the only one we have in the house,” said Lucy, with a mischievous glance at Sadie.

The spring-bed did not fit the bedstead, and the chances were that it might fall through in the night.

“You’re too tremendously kind, too self-sacrificing,” said Preston, suspecting at once that something was wrong.

But he had his revenge. The bedstead was extremely noisy, and the roguish youth, unable to sleep himself on account of mosquitoes, rejoiced to think that he was probably keeping his cousin Lucy awake.

“Good morning, Preston, I hope you rested well,” said she, as they all met next morning in the front yard.

“O very.—it’s so quiet in the country,” returned he demurely. “Did you ever hear anything so quiet?”

“Never; except possibly a saw-mill,” said Sadie Patten. “Lucy and I wondered if you could be alive, you were so still!”

“It was sort of frightful. No sound broke the awful silence, save the warning voice of the mosquito.—By the way, girls, why don’t you call this spot Mosquito Ranch?”

“I’ll tell you what we used to call it at our house,—we always called it ‘Down to the Farm,’” remarked little Fanny.

“It ought to be Rose Villa,” said Lucy. “Just see our rose-tree that reaches almost to the eaves. We measured it yesterday, and it’s seven feet high.”

“That will do for a tree,” said Preston, plucking one of the pure, white roses and thrusting it into his button-hole; “but you can’t eat roses, you know.”

He had built a fire in the kitchen stove, but the young ladies seemed to have forgotten[106] entirely that there was such a thing in the world as breakfast.

“O, yes, we must prepare our simple morning meal,” said cousin Lucy. “Girls, where’s my blue-checked apron? Preston, we’ve heard there are lovely trout in that brook across the field. Not the river-brook.”

“Have you, really? Then I go a-fishing; I’d rather do that than starve.—No, Fan, you needn’t come, I won’t have anybody with me but Flaxie.”

Very proud was Mary that she could be trusted to keep silence in the presence of the wise and wary trout. It was beautiful there by the brook-side, in the still June morning, sitting and watching the “shadowy water, with a sweet south wind blowing over it.” There was no house within half a mile, and perhaps the Peck family and the Brown family—the nearest neighbors—were still[107] asleep, for there was no sound, except the “song-talk” of the birds, and the whisper of the wind through the trees. It was a very light whisper, reminding Preston of the words,—

Mary’s breath was a “noiseless noise,” too; it hardly stirred the folds of her buff print dress; it was the very “sigh” of “silence,” and Preston thought he should tell her so, and praise her when they got home; but it happened that he forgot it.

The trout came, as they usually did when he called for them; but it must be confessed that they were never eaten. Lucy put them in the spider, Sadie salted, Fanny turned, and finally Blanche Jones burned them. The “morning meal” was as “simple” as need[108] be, with cold bread and butter, cold tongue, and muddy, creamless coffee, the milk having turned sour. In the midst of their repast, the young campers were surprised by a loud peal of the door-bell.

“Buttons,” said Lucy to her cousin Preston, “you’ll have to go to the door.”

“Yes,” said Sadie, “as Buttons is the only servant we keep, he must answer the bell.”

Preston obeyed, laughing. A droll little image of dirt and rags stood at the door, holding a ten-quart tin pail.

“Good morning,” said Preston, surprised at the shrewd, unchildlike expression of her face, for she was perhaps twelve years old and looked forty. The little girl seemed equally surprised. “What’s them things?”[110] said she, pointing to Preston’s spectacles. “What do you wear ’em for?”

“Do you want anything, little girl?” asked he, frowning, or trying to frown.

“I say, what do you wear glasses for? You ain’t an old man.”

“No matter what I wear them for—” very sternly. “Do you want anything, child?”

“Yes, I came to ax you for some swifts.”

“What do you mean by swifts?”

“Lor now, don’t you know what swifts is? Swifts is something folks reels yarn on.”

“Well, we haven’t any in this house, little girl, and if that’s all you came for, you’d better run home.”

“Hain’t got no swifts?” shuffling forward with her small, bare feet, and peeping into the house through her straggling locks of hair. “Well, you’ve got a spin-wheel, hain’t ye?”

“No, we’ve nothing you want. You’d better go.”

By that time Mary and Fanny were at the sitting-room door, curious to see the stranger.

“How d’ye do? Do you children live here all alone? Guess I’ll come in,” said the waif, brushing past Preston, who did not choose to keep her out by main force, and entering the sitting-room where the breakfast-table was spread. “I live over t’other side of Bluff. My name’s Pancake.”

“Oh, I know who you are then,” said Fanny, not very cordially; for she had heard her father speak of a poor, half-starved, vagrant family of that name; harmless, he believed, but not very desirable neighbors.

“My name’s Pecy Pancake,” added the waif obligingly, and bent her snub nose to sniff the burnt trout.

“Peace, probably,” said Preston, aside.

“No, Pecielena. Hain’t you got no lasses cake? Oh, what cunning little sassers;” handling the salt glasses. “Where’s the cups to ’em? How came you children to come here alone?”

“We came because we chose,” said Mary, with crushing emphasis.

“We wished to come,” said Fanny, trying to be as dignified as Mary, though she felt her inferiority in this respect always.

In no wise disconcerted, Miss Pecielena Pancake started on a tour of observation about the room.

“You look like you’d been burnt out or somethin’. Who does your work? Got any cow? Oh, you hain’t? Well, I’ve got a cow. This here is my milk bucket. I’ll fetch ye some milk.”

“No, no, no,” exclaimed Lucy, in alarm. “Our milk is to be brought from town.”

“Is, hey? Well, I’ll fetch you some sour milk; five cents a quart.”