| Vol. XX.—No. 980.] | OCTOBER 8, 1898. | [Price One Penny. |

[Transcriber's Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

OUR PUZZLE POEM REPORT: "PREPOSITIONS."

TAME VOLES.

"OUR HERO."

MARY'S PART.

CHRONICLES OF AN ANGLO-CALIFORNIAN RANCH.

VARIETIES.

CHINA MARKS.

RINGS LOST AND FOUND.

JAP DOLL SCENT SACHETS.

LETTERS FROM A LAWYER.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

THINGS IN SEASON, IN MARKET, AND KITCHEN.

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of "A Girl in Springtime," "Sisters Three," etc.

All rights reserved.]

The afternoon post had come in, and the Vicar of Renton stood in the large bay window of his library reading his budget of letters. He was a tall, thin man, with a close shaven face, which had no beauty of feature, but which was wonderfully attractive all the same. It was not an old face, but it was deeply lined, and those who knew and loved him best could tell the history and meaning of each of those eloquent tracings. The deep vertical mark running up the forehead meant sorrow. It had been stamped there for ever on the night when Hubert, his first-born, had been brought back, cold and lifeless, from the river to which he had hurried forth but an hour before, a picture of happy boyhood, in his white boating flannels. The Vicar's brow had been smooth enough before that day; the furrow was graven to the memory of Teddy, the golden-haired lad who had first taught him the joys of fatherhood. The network of little lines about the eyes were caused by the hundred and one little worries of every-day life, and the strain of working a delicate body{18} to its fullest pitch; and the two long, deep streaks down the cheeks bore testimony to that happy sense of humour which showed the bright side of a question, and helped him out of many a slough of despair. This afternoon, as he stood reading his letters one by one, the different lines deepened, or smoothed out, according to the nature of the missive. Now he smiled, now he sighed, anon he crumpled up his face in puzzled thought, until the last letter of all was reached, when he did all three in succession, ending up with a low whistle of surprise—

"Edith! This is from Mrs. Saville. Just look at this!"

Instantly there came a sound of hurried rising from the other end of the room; a wicker-work basket swayed to and fro on a rickety gipsy table, and the Vicar's wife walked hurriedly towards him, rolling half-a-dozen reels of thread in her wake, with an air of fine indifference.

"Mrs. Saville!" she exclaimed eagerly. "How is my boy?" and without waiting for an answer she seized the letter and began to devour its contents, while her husband went stooping about over the floor picking up the contents of the scattered basket and putting them carefully back in their places. He smiled to himself as he did so, and kept turning amused, tender, little glances at his wife as she stood in the uncarpeted space in the window, with the sunshine pouring in on her eager face. Mrs. Asplin had been married for twenty years and was the mother of three big children, but such was the buoyancy of her Irish nature and the irrepressible cheeriness of her heart, that she was in good truth the very youngest person in the house, so that her own daughters were sometimes quite shocked at her levity of behaviour, and treated her with gentle, motherly restraint. She was tall and thin like her husband, and he, at least, considered her every whit as beautiful as she had been a score of years before. Her hair was dark and curly; she had deep-set grey eyes and a pretty fresh complexion. When she was well and rushing about in her usual breathless fashion, she looked like the sister of her own tall girls; and when she was ill, and the dark lines showed under her eyes, she looked like a tired, wearied girl, but never for a moment as if she deserved such a title as an old or elderly woman. Now, as she read, her eyes glowed, and she uttered ecstatic little exclamations of triumph from time to time, for Arthur Saville, the son of the lady who was the writer of the letter, had been the first pupil whom her husband had taken into his house to coach, and as such had a special claim on her affection. For the first dozen years of their marriage all had gone smoothly and well with Mr. and Mrs. Asplin, and the vicar had had more work than he could manage in his busy city parish; then, alas, lung trouble had threatened; he had been obliged to take a year's rest, and to exchange his living for a sleepy little parish, where he could breathe fresh air, and take life at a slower pace. Illness, the doctor's bills, the year's holiday, ran away with a large sum of money; the stipend of the country church was by no means generous, and the vicar was lamenting the fact that he was shortest of money just when his children were growing up and he needed it most, when an old college friend, Major Saville, requested, as a favour, that he would undertake the education of his only son, for a year at least, so that he might be well grounded in his studies before going on to the military tutor who was to prepare him for Sandhurst. Handsome terms were quoted, the vicar looked upon the offer as a leading of Providence, and Arthur Saville's stay at the Rectory proved a success in every sense of the word. He was a clever boy who was not afraid of work, and the vicar discovered in himself an unsuspected genius for teaching. Arthur's progress not only filled him with delight, but brought the offer of other pupils, so that he was but the forerunner of a succession of bright, handsome boys, who came from far and wide to be prepared for college, and to make their home at the vicarage. They were honest, healthy-minded lads, and Mrs. Asplin loved them all, but no one had ever taken Arthur Saville's place. During the year which he had spent under her roof he had broken his collar bone, sprained his ankle, nearly chopped off the top of one of his fingers, scalded his foot, and fallen crash through a plate-glass window. There had never been one moment's peace or quietness; she had gone about from morning to night in chronic fear of a disaster; and, as a matter of course, it followed that Arthur was her darling, ensconced in a little niche of his own, from which subsequent pupils tried in vain to oust him.

Mrs. Saville dwelt upon the latest successes of her clever son with a mother's pride, and his second mother beamed and smiled and cried, "I told you so!" "Dear boy!" "Of course he did!" in delighted echo. But when she came to the second half of the letter her face changed, and she grew grave and anxious. "And now, dear Mr. Asplin," Mrs. Saville wrote, "I come to the real burden of my letter. I return to India in autumn, and am most anxious to see Peggy happily settled before I leave. She has been at this Brighton school for four years, and has done well with her lessons, but the poor child seems so unhappy at the thought of returning, that I am sorely troubled about her. Like most Indian children, she has had very little home life, and after being with me for the last six months, she dreads the prospect of school, and I cannot bear the thought of sending her back against her will. I was puzzling over the question yesterday, when it suddenly occurred to me that perhaps you, dear Mr. Asplin, could help me out of my difficulty. Could you—would you, take her in hand for the next three years, letting her share the lessons of your own two girls? I cannot tell you what a relief and joy it would be to feel that she was under your care. Arthur always looks back on the year spent with you as one of the brightest of his life; and I am sure Peggy would be equally happy. I write to you from force of habit, but really I think this letter should have been addressed to Mrs. Asplin, for it is she who would be most concerned. I know her heart is large enough to mother my dear girl during my absence, and if strength and time will allow her to undertake this fresh charge, I think she will be glad to help another mother by doing so. Peggy is bright and clever like her brother, and strong on the whole, though her throat needs care. She is nearly fifteen—the age, I think, of your youngest girl, and we should be pleased to pay the same terms as we did for Arthur. Now, please, dear Mr. Asplin, talk the matter over with your wife, and let me know your decision as soon as possible."

Mrs. Asplin dropped the letter on the floor and turned to confront her husband.

"Well!"

"Well?"

"It is your affair, dear, not mine. You would have the trouble. Could you do with an extra child in the house?"

"Yes, yes, so far as that goes. The more the merrier. I should like to help Arthur's mother, but——" Mrs. Asplin leant her head on one side, and put on what her children described as her "ways and means" expression. She was saying to herself, clear out the box room over the study. Spare chest of drawers from dressing-room—cover a box with one of the old chintz curtains for an ottoman—enamel the old blue furniture—new carpet and bedstead, say five or six pounds outlay—yes! I think I could make it pretty for five pounds. The calculations lasted for about two minutes, at the end of which time her brow cleared, she nodded brightly, and said in a crisp, decisive tone, "Yes, we will take her. Arthur's throat was delicate too. She must use my gargle."

The vicar laughed softly.

"Ah! I thought that would decide it. I knew your soft heart would not be able to resist the thought of that delicate throat! Well, dear, if you are willing, so am I. I am glad to make hay while the sun shines, and lay by a little provision for the children. How will they take it, do you think? They are accustomed to strange boys, but a girl will be a new experience. She will come at once, I suppose, and settle down to work for the autumn. Dear me! dear me? It is the unexpected that happens. I hope she is a nice child."

"Of course she is. She is Arthur's sister. Come! the young folks are in the study. Let us go and tell them the news. I have always said it was my ambition to have half-a-dozen children, and now, at last, it is going to be gratified."

Mrs. Asplin thrust her hand through her husband's arm, and led him out of the room, down the wide flagged hall, towards the distant room whence the sound of merry young voices fell pleasantly on the ear.

(To be continued.)

Prepositions.

Ten Shillings Each.

Five Shillings Each.

Very Highly Commended.

Rev. S. Bell, E. Blunt, J. A. Center, Edith Collins, R. D. Davis, E. M. Le Mottee, Jas. S. Middleton, Alice M. Motum, H. W. Musgrave, J. D. Musgrave, Mrs. Nicholls, Gertrude Smith, Ellen C. Tarrant, Violet C. Todd, Horace Williams.

Highly Commended.

Guy Baily, Elizabeth A. Collins, Eva Gammage, Mrs. A. D. Harris, Edward St. G. Hodson, Edith L. Howse, Annie G. Luck, May Merrall, F. Miller, Margaret G. Oliver, E. Phillips, M. G. Phillips, Alice M. Seaman, Katie Whitmore.

Honourable Mention.

Mrs. Adkins, Muriel V. Angel, Mrs. Astbury, Mrs. L. Bishop, M. Bolingbroke, Louie Bull, Helen M. Coulthard, Constance Daphne, B. Duret, Annie K. Edwards, C. M. A. Fitzgerald, Edith E. Grundy, Edith M. Higgs, S. D. Honeyburne, J. Hunt, Ethel L. Jollye, Edith B. Jowett, Carlina V. M. Leggett, Mrs. R. Mason, Wm. E. Parker, A. A. L. Shave, Helen Singleton, Clara Souter, W. Fitzjames White, Emily Wilkinson, Henry Wilkinson, Amy G. Wiltshire, Emily C. Woodward, Diana C. Yeo, Sophia Yeo.

The general opinion seems to be that "Prepositions" was a very difficult puzzle. It was certainly unpopular, judging by the number of solutions sent in, but we were inclined to think that this was accounted for by the subject. Who wants to learn anything about prepositions in the middle of summer, and who would be so extremely foolish as to spend any of the precious—not to say "honied"—hours over a grammatical puzzle? In the summer of 1897 about fifteen hundred individuals tried to unravel a page full of curious suppositions. But then suppositions are always dear to the girl mind, while prepositions seldom are, because they pertain to a science which the girl mind (as a rule) little understands. So the subject repelled, and as the difficulty also repelled, we begin to be surprised that there were any solutions at all.

With these unpopular features to contend with, it was particularly unfortunate that the puzzle should have been marred by two serious mistakes. In line 11 no amount of solving ingenuity could convert gr divided by rown into "grown," though a shrewd guess helped nearly all the solvers to the right word. In line 15 the minus sign should have been the sign of division, giving hold divided by u. The point of this mistake was not so widely apprehended, and no wonder.

Of the rest of the puzzle little need be said. Probably the ninth line was the most obscure, and it needed a truly expert solver to discover that lake plus a short line (inserted in the right place) becomes take. The waits were now and then taken for a German band, giving the quaint reading, "But if you take a German noun." Obviously, the alteration that an English preposition would undergo if tacked on to a German noun would be extremely serious, though the precise nature of it would not be easy to define. Many solvers failed to notice that an e was left out of different in line 12. The word was intended to be so written, with of course the addition of an apostrophe, because of the rhythm.

We must not fail to thank M. T. M. for her exceedingly kind and encouraging letter. Referring to our puzzles generally she writes: "I am an invalid, and the diversion of thought and interest is very welcome to me." It is indeed good for us to know that even our more frivolous efforts can be so helpful, and no form of commendation could give us more sincere pleasure.

We append our foreign award on Fluctuations. It is rather late, but we have been anxious to include solutions from the remotest parts of the world. One comes to us from Coomooboolaroo, wherever that may be, and the author mildly suggests that she is afraid her solutions do not arrive in time as she has never had honourable mention. Now that we allow a reasonable extension of time, we hope the writer will continue to solve, for if The Girl's Own Paper can reach even a place with eight os in it so can a Puzzle Poem Prize.

It is very odd, but a puzzle which is popular at home is certain also to be popular abroad.

Fluctuations.

Prize Winners (Seven Shillings Each).

Very Highly Commended.

Ivie D. Ashton, Gertrude Burden (Australia), Ethel Danford (Canada), Lillian Dobson (Australia), Aveline Gall (Demerara), Maggie Glasgow, Mrs. Hardy (Australia), Mrs. Manners, Maud C. Ogilvie (India).

Highly Commended.

Evalyn Austin (Australia), M. C. C. (Ceylon), Mrs. F. Christian, Lily Harman, Harry John (India), Philippa M. Kemlo (Cape Colony), Elizabeth Lang (France), Frances A. L. Macharg (S. Africa), Grace Rhodes (Australia), Frances E. Scott (Austria), Mrs. Sprigg, Mrs. F. H. le Sueur (Cape Colony), A. G. Taylor (Australia), Dora M. C. Webbe (New York).

Honourable Mention.

Mrs. G. Barnard (Australia), Annie Barrow (Switzerland), Winifred Bizzey (Canada), Mabel E. Broughton (Australia), Marcelle Crasenster (Belgium), Elsie V. Davies, Barton Egan (Australia), Hattie L. Elliot (Canada), Lena Gahan (Burma), Ethel L. Glendenning (New Zealand), Dora von Grabmayr (Austria), Agnes Henderson (S. Africa), Violet Hewett (Canada), A. Hood (France), Annie Jackson, Mabel C. King (Canada), Blanche Kirkup (Russia), Mina J. Knop (India), Percival Laker (Australia), Mrs. J. R. Lee (Burma), Annie Leipoldt (S. Africa), Mrs. G. Marrett (India), Gertrude E. Moore, Amy F. Moore-Jones (New Zealand), Annie Orbiston (Australia), E. Nina Reid (New Zealand), Hilda D'Rozario (India), A. Shannon (Australia), Laura O'Suleivan (Burma), J. S. Summers (India), Gladys Wilding (New Zealand), Elsie M. Wylie (New Zealand).

One day last August, when strolling in a secluded part of my garden, I was surprised to see some little brown mice playing about and racing after each other without at all regarding my presence.

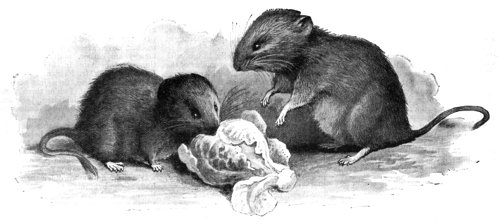

I stood and watched these playful gambols, and soon discovered that the little animals were short-tailed field-mice, or voles, as I believe they ought to be called. Some differences in structure separate the voles from the true mice and rats; they also differ in their food, the voles being almost entirely vegetable feeders.

The water-rat, so called, is a vole and a perfectly harmless little animal. I often endeavour to explain this fact to farmers and working-men, who seem to think they have done something meritorious when they have hunted to death one of these voles, whose harmless diet consists chiefly of duckweed, flag, rushes, and other water-plants; but, unfortunately, it looks like a land rat, and so it has to suffer for the evil reputation of its relative.

There are two small voles, the red field-vole and this commoner short-tailed species which inhabits my garden.

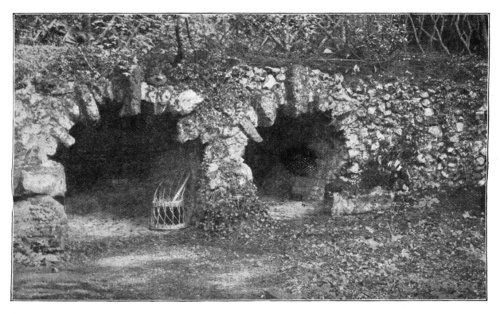

I had often wished to catch and keep these little animals as pets for purposes of study; and, finding some specimens already so tame, I began to entice them to come to a special place under a stone archway by daily strewing at exactly the same spot some oatmeal and canary seed.

Very soon the tiny creatures would allow me to stand and watch them feeding, and I drew nearer and nearer until I could almost touch them.

I then put a mouse-cage under the arch in the hope that they might accept it as a home and thus be led into voluntary captivity. This new idea met with a measure of approval, for one little vole scooped out a small cavity beneath the cage and appeared to make itself quite at home there, even allowing me to lift up the cage without moving, gazing curiously at me with its small black eyes.

This went on from August until October. The voles and I grew to be quite good friends; but, as the colder weather would soon be hindering my daily visits, our friendship would have to cease unless I could bring my small pets indoors.

It struck me that they might be coaxed into captivity by another device. I placed a glass globe under the arch, containing their favourite food, and a piece of wood leaning against the globe to enable the mice to climb up and leap in.

When I went next morning there was a little vole inside the globe and by no means frightened, for it allowed me to stroke its soft fur without alarm.

I have had great pleasure in watching the graceful attitudes of this small creature. It sits up like a squirrel holding a grain of wheat in its paws; then, its meal over, it thoroughly cleans its fur, brushes its whiskers, and performs a careful toilet before going to sleep, curled up in a lump of cotton wool and moss.

My ultimate aim being to obtain some baby voles to be trained into absolute tameness, I set to work to secure a mate, and placed the globe as before, baited with tempting food.

In a few days' time I caught a second vole, and now Darby and Joan live happily together in a square glass case where they have room for exercise and where I can see and record their doings.

All this may seem to some readers exceedingly trivial and not worth writing about; but, seeing that we cannot be all day out-of-doors making observations about these and other subjects of study, there seems some use in keeping creatures in happy captivity, because one can thus become ultimately acquainted with them and learn many facts about their life and habits which would otherwise be difficult or impossible to observe.

I am now testing their liking for various plants, and after a time I may be able to make a list of the weeds they consume which may possibly be a set-off to the damage they do in other directions.

Voles have an acute sense of smell, as I learn in this way. The little pair may be sound asleep in their bed of moss and wool, but I no sooner place an earthy root of groundsel or chickweed in their glass case than I see an inquisitive nose at the entrance of the dormitory sniffing the air, and in another minute out comes mousie to enjoy the feast of fresh greenery.

The winter passed by uneventfully, until on the morning of January 26th I heard quite loud growls and squeaks proceeding from the voles' residence.

The cotton-wool quivered and was upheaved by unseen forces. Something serious must evidently be going on, so I cautiously interfered.

In lifting the woollen mass I disturbed four little sprawling infants of a bright pink colour and no particular shape! They were, of course, speedily replaced, and I could well understand the state of affairs.

The father mouse must be removed somehow{21} as he was evidently in the way and quite upsetting the nursery arrangements, but how I was to tell which was which was a real puzzle.

I thought I would try to learn a lesson from the wise king of old and see whether maternal love would not prove a sure test. I thought I would allow the vole that first returned to the nest to remain and place the other in a separate globe.

The plan was successful, for the mother mouse went back to the nest at once and set to work to repair the dwelling which I had somewhat disarranged.

The young voles were by no means beautiful. Bright red in colour, the thin hairless, almost transparent, skin allowed one to see the beating of the heart and its circulation very plainly.

The head was nearly half the length of the body, and the eyes were, of course, closely shut, yet, feeble though they were, when only two days old the small creatures were full of life, and resented being touched by giving angry little kicks and plunges. Indeed, I never knew any family so forward.

I purposely stroked and handled the four small mites daily so that they might grow up to be perfectly tame from their babyhood. In doing this I noted one or two rather curious traits of instinct.

Whilst still quite blind, the young voles, if placed on a table, would invariably creep backwards and continue a retrograde movement, until at last they would have fallen over the edge of the table if I had allowed them to do so.

I imagine nature teaches this evolution so that, in their native burrow, these defenceless weak young creatures may invariably retreat as far back as possible out of the reach of danger.

About ten days later, whilst I was holding one of the young voles in my hand in order to take its portrait, it surprised me by sitting up and beginning to clean its fur and whiskers as carefully and neatly as if it had been a cat by the fireside, even licking each little paw in succession until its toilet was complete. The creature was only thirteen days old and still quite blind, so it shows how soon instinct teaches the important lesson of cleanliness.

On the morning of the fourteenth day the little mice could see and became quite enterprising, nibbling lettuce leaves and oatmeal and roaming about their small domain. A little later on they could feed themselves, and I believe I ought then to have taken away the hard-worked little mother, for I imagine family cares and worries must have accounted for my finding poor Joan had died on the very day when I purposed letting her and her mate have their liberty.

I set Darby free in his old home under the archway, where no doubt he will soon find another mate, and I shall probably discover by their depredations in my garden that he has reared strong and healthy families to prey upon my cherished plants and trees.

At present the young voles are by no means tame, and still indulge in kicking, squeaking, and scratching if I attempt to stroke them, but I have learnt a good deal about their domestic life and derived a great deal of amusement from my experiment in vole-rearing.

Eliza Brightwen.

A TALE OF THE FRANCO-ENGLISH WAR NINETY YEARS AGO.

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of "Sun, Moon and Stars," "The Girl at the Dower House," etc.

HOW MOLLY HEARD THE NEWS.

"Molly, Molly, listen to me. I've something to tell you, Molly."

"What is it?"

"Put that book down. What are you reading? The History of a Good Little Girl. Oh, I know; and there was a naughty boy, who tied a string across the stairs, and the grannie tumbled down and broke her leg. That's all; at least, she got well again, and he was sorry, and never did anything naughty again. So now you know, and you can stop. Listen to me, Molly."

Roy jerked the book out of his twin-sister's hands. It was not a handsome and well-illustrated volume, like those now in vogue, but it was bound in dull boards, and the woodcuts were fantastically hideous. To Molly Baron, who had never seen anything better, such a volume brought delight. She loved reading, while Roy hated it, unless he found a book about battles.

Molly had a pale little face, with large anxious black eyes, and short dark hair, brushed smoothly back. She wore a frock of thick blue stuff, short-waisted and low-necked, while her thin brown arms were bare.

Nobody else was in the schoolroom, which served also as a playroom for the two children. Its furniture was scanty, including no easy-chairs or footstools, but only straight-backed hard-seated chairs and backless wooden stools. Mrs. Baron was a mother unusually given to the expression of tender feeling, in a sterner age than this of ours; but even she never dreamt of permitting her children opportunities for lounging. They had to grow up straight-backed, whatever might befall.

In this room Roy and Molly had done all their lessons together, till Roy reached the age of nine years; and the day on which he began to attend a day-school had witnessed the first deep desolation of little Molly's heart. An ever-present dread was upon her of the coming time—she knew it must come—when he would be sent away to a boarding-school, and she would be left alone. But as yet no date had been named to her, and she hugged the present condition of affairs, trying to believe that it would go on indefinitely.

Since Molly had read the book at{22} least six times already, she made no protest, but simply waited to hear the news.

"Guess what's going to happen. Guess, Molly."

"How can I tell? What sort of thing?"

"I'm going to France—to Paris!"

Roy turned head over heels, and came right side up again.

"Why? What for? Why are we going?"

"I didn't say you. I said I was. Papa and mamma mean to take me with them. And Den too."

"And not—me!"

Molly held up her head resolutely, trying not to let even her lips quiver. She gazed hard at the opposite wall.

Roy was far too much absorbed with his own prospects to notice her distress. To leave Molly for the delights of foreign travel meant nothing to him, though, had she been the one to go, and he the one to stay behind, he would no doubt have felt differently. In all their lives the twins had never yet been separated for more than one or two nights. Naturally, however, when the first real separation came, it would mean more to the girl than to the boy. Roy had to the full a boy's love of novelty.

"We shall go over the sea, and then I shall know how the sailors feel. If I wasn't going to be a soldier I should want to be a sailor; but of course I'm going to be what papa and Den are, and I like that best, only I've got to wait longer for it. And we shall stay in Paris, and there will be mounseers everywhere. Won't that be funny? And I shall write and tell you all about it"—as her silence dawned upon him. "And you'll have Jack and Polly, you know."

"If I was going to Paris, would you think Jack and Polly enough instead?" demanded Molly, out of her sore heart, still staring fixedly at the wall. A great lump was struggling in her throat.

"But you're not going, and I am. And you and Jack can have fun together."

"Jack's grown up; he isn't a boy, like you." Molly would have liked much to add, "He isn't my twin, Roy," but at the bare idea of saying such words her whole heart seemed to rise up in one huge billow, and very nearly swamped her self-control. She had to clench her hands and to bite her lips fiercely. If Roy did not care about leaving her, she was not going to let him see that she cared about losing him.

Roy seated himself astride on a chair, with his face to the back, and told his tale. He described his position outside the drawing-room window, and related the stray words which had reached his ears, making no secret of the fact that he had done his best to hear more. A glitter appeared in Molly's eyes, as she listened, and when the story was ended she said, with a catch of her breath—

"I think I shouldn't be so glad to go if—if you—weren't going too. And I shouldn't like to be you, to have listened on the sly. It was mean."

Roy sat motionless. That view of the matter had not yet occurred to him. He dismissed Molly's first words as unimportant, being merely a girl's unreasonable view of things, with which he as a boy could not be expected to agree. But that he—Roy Baron, son of a Colonel in His Majesty's Guards—should be accused of "meanness!" The word stung sharply. Roy always pictured his own future in connection with a scarlet coat, a three-cornered cocked hat, a beautiful pigtail, and the stiffest of military stocks to hold up his chin. He knew something of a soldier's sense of honour, and even now he felt ready to fight his country's battles. And that he should be accused of meanness—and by a girl!

"I do think so," Molly added. "It was horridly mean. Prying into what you weren't meant to hear! And then coming and telling me! If I had done such a thing, you'd have been the first to call it mean."

Roy stood bolt upright.

"You needn't have said it to me like that!" he said. "You might have told me, Molly—different, somehow. But I wouldn't be mean for anything, and I'm going to tell papa, straight off."

Roy did not ask Molly to go with him, and she was keenly sensible of the omission. He marched off alone, carrying his head as high as if the military stock had already encircled his throat. When he went into the drawing-room there was a pause in the conversation; and this seemed to show that Molly was in the right. She might be cross, but perhaps she had judged correctly.

"Run away, Roy," the Colonel said. "We did not send for you, and we are busy."

"Please, sir, may I say something first?" Roy advanced unfalteringly, and stood in front of the Colonel.

"Well, be quick, my boy. You are interrupting us."

Roy's honest grey eyes met his father's. "I was out there," he said, pointing to the verandah. "And I heard something. I didn't think about its being a secret, and I listened. I heard about going to Paris, and I—I went and told Molly. And she said it was mean of me. And I—couldn't be mean, sir!"

"No, Roy, you couldn't," the Colonel answered with gravity, while delighted at the boy's openness.

"I didn't mean any harm; but I suppose I oughtn't to have listened. I won't ever again, sir."

"Well, yes; of course that was wrong," the Colonel said, with a careful choice of words. "You should have told us that you were there. And you must not look upon the plan as—ahem—as quite settled. We are merely discussing it; and we might change our intentions——"

"I am sure, my dear sir, I heartily wish you would," chimed in Mrs. Bryce.

The Colonel made her a stately bow.

"And if I had found you out, Roy, overhearing us, I should certainly have blamed you. But as you have voluntarily confessed it, I"—the Colonel hesitated, conscious of his wife's pleading gaze—"well, we need say no more about the matter. You have acted rightly in coming at once to me; and I am convinced that you will not do such a thing again. Now you may run away."

Roy bounded off in the best of spirits, and Mrs. Bryce remarked, "There is an opportunity to give up your scheme. Best possible punishment for the boy. Were he my boy he should suffer for his behaviour."

"But Roy is my son," the Colonel said, and there was an accent of pride in his voice.

The pretty girl, with tall feathers in her bonnet, glided softly out of the room after Roy. She did not follow him far. She saw him vanish in the direction of the garden, flourishing his heels like a young colt, and she went the other way, towards the school-room. For Roy had told Molly about the Paris plan, and Polly guessed what that would mean to Molly.

Mary Keene and her brother John, commonly known as "Polly" and "Jack," were not really cousins to Roy and Molly, though treated as such by the family. Their widowed grandmother, Mrs. Keene, had, some fourteen years earlier, married a second time—rather late in life—and her new husband, Mr. Fairbank, had one daughter, Harriette, then just married to Captain Baron. Two or three years later her own grandchildren, Jack and Polly, were left orphans, and were taken in permanently by Mr. and Mrs. Fairbank. When Mr. Fairbank died, some four or five years before this date, his twice-widowed wife took up her abode, with her grandchildren, in Bath, then a fashionable place of residence for "the quality." Jack, who was a year and more older than Polly had, at the beginning of this story, just been gazetted to a regiment of the line, which was quartered in Bath.

Molly was very fond of Polly, and she had also a warm admiration for Jack; but no one in the world could be to her like her own twin-brother, Roy; and Roy's indifference to this first serious separation had cut her to the quick. When Polly entered the schoolroom, she at first thought that Molly had fled; but she detected a little heap in the farthest and darkest corner, and soon she heard the sound of a smothered sob, followed quickly by a second and a third.

Polly waited a moment, to draw off her gloves, and then she made her way to the corner, sat down on the ground, and put a pair of gentle arms round the child.

"O fie, little Molly, fie! This won't do at all, you know. Crying to have to go home with me! That is altogether wrong and silly. And so unkind too. It makes me feel half inclined to cry also, because I wanted to have dear little Molly, and now I know that Molly does not care to come. Molly, you dear little goose, don't you know that people can't be always and for ever together the whole of their lives? It isn't the way of the world, dear; and you and I can't alter the world to please ourselves. Roy is glad to go to Paris, of course; and so would you be, and so should I{23} be, in his place. But everybody can't go to Paris at the same time. Fie, fie, little Molly, to mind so much what isn't worth making your eyes red about! Fie, dear! Wake up, and don't be doleful. Always laugh, if you can; because if you are unhappy, it makes other people unhappy as well. And that is such a pity. You don't wish to set me off crying too, do you?"

The elder girl's eyes had a suspicious look in them of tears not far off, as she bent over the child.

"Other people have troubles, as well as you, little Moll. Try to believe that, and try to be brave. We don't all—I mean, they don't all talk about their troubles always. It is of no use. Things have to be borne, and crying does no good. So stop the tears, Molly, and hold up your head, and think how nice it will be to see my grandmother and Jack, and the Bath Pump-room, and all the fine ladies and gentlemen walking about in their smart clothes."

A squeeze of Molly's arms came in reply.

"There will be Admiral and Mrs. Peirce to see, for the Admiral is now at home, and they are in Bath—and little Will Peirce, who soon is to be a middy in His Majesty's Navy. And Jack shall show himself to you in his new scarlet coat. You would not think how well he looks in it. I am proud of him, and so must you be; for Jack is everything in the world to me. No, not quite everything, but a great deal, as Roy is to you. Yet, I do not expect always to keep Jack by my side. He will have to go some day, and he will have to fight for old England. And when that day comes, I shall bid him farewell with a smile; for I would not be a drag upon him, nor wish to hold him back. And Roy will go also; and you will bear it bravely, little Moll. I am sure you will—like a soldier's daughter."

The soft caressing voice, the cool rose-leaf cheek against her own, the lovely dark eyes smiling upon her, all comforted poor Molly's sore heart; and she clung to Polly, and cried away more than half her pain.

"Don't tell Roy," she petitioned presently. "He doesn't mind, and he must not think that I do."

"Why not? That is naughty pride, Molly. It is always the women who care, not the men." Polly held up her head, and a far-away look crept into the soft eyes. "Dear, you must expect it to be so. Men have so much to do and to think about. But we have time to grieve, when they go away to fight; and they are always so glad to go."

"Are they?" a deep and quiet voice asked, close to her side, and Polly started strangely. For a moment her tiny shell-pink ears became crimson, and then she looked up, smiling.

"How do you do, Captain Ivor?"

Denham Ivor in his uniform—large-skirted military coat, black gaiters, white breeches, pig-tail, and gold-laced cocked hat in hand—looked even taller than out of it, and at all times he was wont to overtop the average man. He had a fine face, well browned, with regular features and dark eyes, ordinarily calm, and he bore his head in a stately fashion, while his manners were marked by a grave courtesy, which might seem strange beside modern freedom. As he looked down upon Polly, a subdued glow awoke in those earnest eyes.

Polly had not sprung up. She was still kneeling on the floor beside Molly, and her slim figure in its white frock looked very child-like. The flush had died as fast as it had arisen. Molly was clinging to her, with hidden face, and for an instant the fresh voice failed to reach the younger girl's understanding. Then Molly became aware of another spectator, and quitting her hold, she fled from the room. Polly rose gracefully.

"We will now go to the drawing-room," she suggested.

"Nay, wait a moment, I entreat. One instant"—and the bronzed face had grown positively pale. "I beseech of you to listen to me. For indeed, I have somewhat to say which I can no longer resolve to keep to myself. No, not even for one more day. Somewhat that you alone can answer, thereby making me the most happy or the most miserable of men."

A tiny gleam came to Polly's downcast eyes.

"If you have aught that is weighty to say, it may be that I could but refer you to my grandmother," she suggested demurely.

"But perhaps you can divine what that weighty thing is. And what if already I have written to your grandmother; and if she has consented to my suit?"

Young ladies did not give themselves away too cheaply in those days. Polly was barely eighteen; but, for all that, she had a very dainty air of dignity. And if, during past weeks, she had gone through some troublous hours, recognising how much she cared for Captain Ivor, and wondering, despite his marked attentions, whether he seriously cared for her, she was not going to admit as much in any haste to the individual in question. So she dropped an elegant little curtsey, and asked, with the most innocent air imaginable—

"Then, pray, sir, what may be your will?"

"Sweet Polly, may I speak?"

A solid square stool—well adapted for present purposes—was close at hand, and promptly down upon this with both knees went the tall grenadier, in the most approved fashion of his day. Sweet Polly could not long stand out against his earnest pleading. So, with a show of coy reserve, she gradually yielded, intimating that she did like him just a little; that some day or other she thought she could be his wife; that meantime she would somehow manage to keep him in her memory.

"And next week you are away to Paris!" she said, perhaps secretly wondering why he did not prefer to spend his leave in Bath. "For a whole long fortnight!"

"I could wish that I were not going. But all is arranged and the Colonel desires it. I must not fail him now at the last. If I can see my way to return at the end of a se'night, I will assuredly do so. If not—I shall still have a fortnight after my return. I shall know what to do with that time, sweetheart."

It is to be feared that Polly found small leisure thereafter for meditating on the childish woes of little Molly, so full was her head of the brave young Grenadier Captain, who had vowed to devote his life to her.

Just one or two weeks of separation, and then she would have him with her again; and hers would be the ineffable delight of showing off this gallant lover among all her Bath friends. How they would one and all envy Polly!

A small touch of feminine vanity no doubt crept in here, though Polly's whole girlish heart was given to Denham. But in his deeper love for her there was no thought of what others might say. He would, of course, be proud of the fair creature whom he had won; yet in his love there was no room found for the puerile element. It pervaded the man's entire being.

He stood very much alone in the world as regarded kinship, having been left an orphan at an early age, under the guardianship of Colonel Baron, his father's cousin, and having no brothers, sisters or other near relatives. The Barons' house had been, ever since Colonel Baron's marriage, a home to him; and while Colonel Baron was in some sense almost as his father, Mrs. Baron occupied rather the position of an elder sister. To Roy and Molly, Denham had always been like a brother. He had seen a good deal of both Polly and Jack in their childhood, but during later years he had been much on service abroad; and his first view of Polly Keene, his quondam playmate, transformed into a grown-up young lady, had been but a few weeks before this date. Denham had lost his heart to her in the first half-hour of their renewed acquaintance; and Polly soon discovered that he was the one man in the world who had her happiness in his keeping.

Despite the warm affection of his Baron cousins, Denham had possessed hitherto none as absolutely his own. Now that he had won "Sweet Polly," life would wear for him a new aspect.

And when, three or four days later, good-byes were said, no voice whispered to him or to Polly, how long-drawn-out a separation lay ahead.

(To be continued.)

By WILLIAM T. SAWARD.

By MARGARET INNES.

It has been suggested that the experiences of some English people in search of and on a ranch in California might be of interest to others, especially, perhaps, to those who are looking about more or less anxiously to find some promising opening for the future of their boys, and who, seeing the Old World so crowded, and realising the difficulty of finding a possible niche at home, may desire to try an altogether new life in the New World.

Many fathers and mothers, also like ourselves, would fain discover, if possible, some way of keeping their boys beside them; some business which they can work together, and in which they may find a satisfactory livelihood for all. Of course, I am speaking of those who have no well-established family business or firm; for them many difficulties and anxious questions are solved.

These were the reasons, together with the delicate health of our two boys, and my own long-standing lung trouble, which, after much thought and study, led us to pack up all our worldly goods, label them "Settlers' effects," and start off on the weary long journey of 6,000 miles, to the land of sunshine, on the Pacific coast. Having some acquaintances living at a little summer holiday place on the coast, and within some seventeen miles of the busy and enterprising town of Los Angeles, we decided to go there, and, if convenient, make it our headquarters while looking about and getting all possible information on the important subject of ranching.

We arrived about the end of October, when the heat of summer was over; for even on the coast, the glare of full summer is trying to people coming from northern latitudes.

But we found the climate most exquisite all the winter. The sunshine was perfectly glorious; the colours, the distances and the sunsets were like fairyland. Indeed, they were quite an excitement to us, and we would often come to a sudden standstill in our evening walks to watch the splendid transformation scene, saying how exaggerated everyone would think our descriptions, if we tried to put them all down exactly, on paper. It is true Holman Hunt had such colours in his pictures of Palestine, but it needs a genius to make such impossible colours accepted as realities.

The little town is built near the edge of the bluffs, and it was delightful to sit under the eucalyptus trees and look out at the sea, so wonderfully blue, with its broad white fringe all round the bay, where the big rollers broke on the yellow sands, and rushed away up the level shore.

The happiness too of all the living creatures seemed quite infectious. We saw flocks of dainty wee sea-ducks, tumbling and swimming about in the sea, just where the huge rollers broke, vying with each other in the show of bravery, going under with the huge crest of a wave and bobbing up again, so rapidly, and with a jaunty toss of the head. Enormous golden brown butterflies came floating down the soft air and hung over the white surf.

Schools of porpoises made the most demonstrative show of enjoyment, jumping high out of the sea and careering round, in a rushing mass, that would churn up the water as they went into a perfect whirlpool. Here and there, in the quiet evening, the head of a friendly seal would appear silently, and then go under without a ripple.

Stately, solemn-looking pelicans, too, flew past constantly, always in single file, as though they were going to some grave and important function. There were crowds of blue birds, looking like jewels in the bright sunshine; and the humming-birds made quite a noise with their wee wings round our honeysuckle-covered verandah.

Every living thing seemed to have just discovered how gay and charming a thing life was.

All this helped to give us a very favourable impression of the new land, and to heal a little the painful home-sickness and longing that beset us almost at once, when we realised more and more the strangeness of much around us.

Finding, on arriving there, that this little town would suit us for some months, we "rented" a pretty little house of seven or eight rooms, with a good verandah, shaded with honeysuckle, and a small garden, for which we paid thirty dollars a month.

Many of the ranchers from the inland valleys come there for three or four of the{26} summer months, as the heat is then almost unendurable anywhere out of reach of the sea breeze. We had been advised to bring a servant with us from England; for help of every kind is very expensive, all over the States, and especially in California. The usual wages are twenty-five dollars a month for women servants, and thirty to forty dollars for a Chinaman.

Unfortunately we were not able to bring a well tried and trusted servant, but had to content ourselves with choosing the best we could from a large number who, tempted by the high wages, came to be interviewed, in answer to our advertisement; but only very few of the applicants were at all suitable.

The usual plan as to the fare—which is of course expensive—is to make a clear and binding arrangement with the girl engaged; that it shall come out of her first six months' wage, also that she shall give a promise to stay at least two years, and that after this period she shall receive the full California wage, having, meanwhile, been paid somewhat less. These arrangements were all made, most clearly in our case, and were at once forgotten by our carefully chosen maid. She was an absolute failure, so far as we were concerned, and as few people out here ask any character when engaging a servant, it was quite easy for her to get another place at once at the usual high wages and simply march off and leave us; which she did.

Our house agent, a kindly Englishman, who had been many years in California, told us that even if we desired to go to law about it, the case would most certainly be given against us. The jury would be composed of men, all more or less of the same class as our servant, and their sympathies would be with her, and we should not have the least chance of getting justice.

It was rather comforting, at the time, to find how many others among our acquaintances had gone through the same experience!

Before this catastrophe came about, however, we had been exceedingly busy visiting innumerable ranches and examining possible and impossible land that was waiting to be made into ranches. We saw most of the well-known "settled-up" parts, and many lovely valleys and foothills which were said to be the coming fruit districts of the near future.

It takes some years for English eyes to get accustomed to the bareness of the hills of California, or to find out the true beauty of these dried-up looking slopes. Once the love for them begins, however, it grows at a great pace, and one discovers constantly fresh wonder and charm in them. Surely no other hills have the gift of holding the splendid sunset colours with such transfiguring power. Even the Alps cannot outrival them in this. But at first it is their uncompromising bareness, dryness and barrenness which hurts one's sensitiveness. We were also disagreeably impressed by the tracts of waste ground, lying promiscuously among the more finished streets, and all scattered over with empty tins and other rubbish, giving a decided effect of disorder and unkemptness, even though the neighbouring houses might be pretty and have dainty gardens. Some of the older established fruit districts were very prosperous looking, and had quite a busy social life. But our minds were quite made up, that of what the land had to offer, we would, without hesitation, choose a real country life, free and untrammelled, in one of the less settled neighbourhoods.

However we conscientiously went to see all the most promising parts, and in this way we learnt a great deal. We found that in this part of Southern California the heat during the summer months was so very great, that all who had the means to do so, left these inland valleys and came every summer to the coast for three or four months, leaving a reliable man in charge, and also going back and forward several times to see that everything was being well cared for. To many people this would be no drawback, but only a pleasant change. We did not wish, however, to settle in any place where we should be absolutely compelled to leave home for so long every year.

Another disadvantage of buying a ranch in one of these established parts is the very high price demanded for all such land. However, it is an open question whether it really costs more in the end to buy a ready-planted and bearing ranch at the very high figure generally quoted.

If you buy in a less settled neighbourhood the rough untouched land at a tenth of the price—which would be about the cost of good land with water—there is the hard work of clearing and grading, laying out, planting and piping it. Then the long waiting before the trees can bring in any income, and when household and ranch expenses have to be met, must be counted as so much more money invested. It is just here that so many sad failures occur.

There has been so much exaggeration about the wonders of California, that those who have caught from such one-sided accounts the fever of longing for the sunshine and free life, do not make allowance for this necessarily long pause before any income is possible from a ranch. Thus it comes to pass that so many ranches are mortgaged; and when a ranch is mortgaged, it is a hopeless business for the poor rancher who has worked so hard at his unaccustomed labour.

It has been said that small fruit—berries of different kinds—may be grown meanwhile, and that the profits from these will help out the expenses until the ranch trees bear. If you are made of cast iron, you may possibly be able to give the necessary work to your ranch, and at the same time cultivate small fruit; but if you come from the ordinary comfortable middle-class at home, you cannot have the strength or resistance to stand this additional toil.

I believe there is a vague but sanguine idea among those at home, bitten by the Californian fever, that you have only to plant trees or vegetables and then sit down comfortably in the sunshine and wait for them to grow, condescending eventually to put aside your book and your pipe for a little while, and gather in all the rich harvest which this wonderful climate has produced for you. This is not so. Ranching is really hard work, and moreover the greatest strain of the life to men coming from a different climate, is that all this unaccustomed labour has to be done in the hot glare of unbroken sunshine.

(To be continued.)

It Strikes one as Remarkable.

A train starts daily, let us say, from San Francisco to New York, and one daily from New York to San Francisco, the journey lasting seven days. How many trains will a traveller meet in journeying from San Francisco to New York?

It appears obvious at the first glance that the traveller must meet seven trains—and that is the answer which will be given by nine girls out of ten to whom the question is new.

The fact is overlooked that every day during the journey a fresh train is starting from the other end, whilst there are seven on the way to begin with. The traveller will, therefore, meet not seven trains but fourteen.

The Two Sacks.

Imitated from Phædrus.

In Debt for Ever.

A man who owes a shilling, proceeds to pay it at the rate of sixpence the first day, threepence the second day, three half-pence the next, three farthings the next, and so on—paying each day half the amount he paid the day before.

Supposing him to be furnished with counters of small value, so as to be able readily to pay fractions of a penny, how long would it take him to pay the shilling?

The answer is that he would never pay it. It is true that he would pay elevenpence-farthing in four days, but after that his progress would be slow and he could never get out of debt.

Good Verses by a Bad Poet.

Few things in Dryden or Pope, it has been remarked, are finer than the following lines by a man whom they both continually laughed at—Sir Richard Blackmore—

Love of Country.

Churchill.

The Passing Cloud.

Cloud and storm only intimate the passing commotion needful to purify the air and the water; and compared with the azure depths above and below, they are superficial and transitory. They retire, and the beautiful blue of heaven reappears, and the ocean again becomes a sapphire foundation on which the sun scatters his jewels of light with regal lavishness.

And so no dark trial, no grievous judgment, can cross our sky without revealing some spot of heavenly blue in the midst of it, or if concealed for a moment, breaking forth again with greater brightness and beauty.

Rev. Dr. Hugh Macmillan.

ENGLISH PORCELAIN.

The name porcelain is derived from the Italian porcellana, signifying a cowrie shell, on account of the delicate translucent glaze on its surface. At how early a date the manufacture of pottery began in this country, before the Roman invasion, is not absolutely known. In the Anglo-Saxon times the pottery of the Celtic tribes was confined to the manufacture of cinerary urns and very common utensils of household use; as they preferred the employment of glass and horn for drinking purposes, and metal or wood for solid food. In the thirteenth century pottery was reinstated in public favour; and a great advance was made in the art, a glaze being employed from the fourteenth to the beginning of the sixteenth century, when a new description of pottery was invented, a salt-glazed stoneware, which came into the market with importations of Italian fayence and oriental porcelain.

It was not until the good Père d'Entrecolles introduced into this country the learning of that ancient Empire of China, in the mysteries of the ceramic art, that our own ideas became enlarged and elevated above the improvements made in our potteries. The Père, being a resident in a district distinguished for its porcelain manufactories, sent samples to his own country (A.D. 1727, 1729,) with information as to the substances employed at King-te-Chin, for which kilns affording greater heat and suitable for firing the differently-coloured enamels were employed.

Hard paste was made at Plymouth, Bristol and Lowestoft, and the soft paste at Chelsea, Bow, Derby, Nantgarw, Liverpool, Pinxton, Swansea, Rockingham, Worcester, Shropshire and Staffordshire; felspar being superadded in the latter two manufactories. The soft paste is produced from an alkaline flux, combining chalk, bone-ash, sand or gypsum.

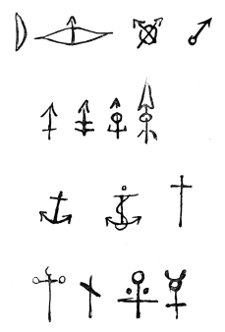

At Stratford-le-Bow (called "New Canton") soft-paste china was produced in the old pottery works, believed to have been established in 1730, though little is known of them till 1744, when Edward Heylin and Thomas Frye, a painter, took out the first patent, and a second in 1749. The marks attributed to these works are as here illustrated.

The glaze on the Bow ware was very brilliant, but sometimes erred in point of thickness. The blue china was generally decorated with birds, flowers, figures and Chinese landscapes. A pattern of hawthorn was a favourite, consisting of two sprigs united. The bow and arrow mark is usually found on small objects, and the dagger and anchor, with a crescent at times, appears on figures. A small blue crescent, with the horns turned up, have also been used. The monogram of Thomas Frye, sometimes reversed, identified some figures from the Bow works at a date previous to 1760. Many variations of Frye's signature have been used by the workmen of this factory; too many for the space at disposal in these columns. It was carried on for many years by Messrs. Crowther and Weatherby, who employed some ninety painters, of whom one was Thomas Craft. The Bow paste is very hard and compact, and therefore heavy. But the most delicate ware was also produced; as in cups and saucers, which were like egg-shells in thinness, and of a milky whiteness.

Under Thomas Frye the china was brought to great perfection. It was after him we find that the works passed into the hands of Weatherby and Crowther, and were closed by the bankruptcy of the latter in 1763, Weatherby having died the previous year.

I may observe that sprigged tea-sets, Dresden sprigs and white bud sprigs—all very popular patterns—were largely produced at Bow, in addition to landscapes and dragon services; also statuettes and groups of figures, vases, etc.

The Chelsea manufacture of china is said to date from Cenvirons, 1745-49, but a species of porcelain was produced in a glass factory at Chelsea in 1676, established there by some Venetians, patronised by the then Duke of Buckingham. Clay from Dorsetshire, sand from the Isle of Wight and kaolin, and chinastone from Cornwall and Devonshire, were employed at this factory. An anchor sometimes barbed, and at other times with amulets, and one within a double circle; as also a triangle, with the name "Chelsea," and the date "1745" beneath it, were the marks chosen to distinguish this ware. On the finest specimens the anchor is gilt, on those of second quality in red, brown or purple upon the glaze.

The porcelain of Chelsea bears some resemblance to that of Venice of about the same date—the Cozzi period, 1780—which is natural, the founders of the manufactory having been Venetians; and the porcelain produced there stands amongst the very first of our English ceramic works in every respect, ranking higher than that of Bristol. The workmen were originally procured from Bow, Burslem and other works; the china manufacture being carried on at first by William the Duke of Cumberland and Sir Everard Faulkenor, the latter dying in 1755 or 1758, and the former in 1765, when Sprimont became sole proprietor. Three blemishes, or spots, characterise the china of this factory, appearing at equal distances where the glaze has been removed, apparently by contact with what the article rested upon.

The work executed at the Chelsea factory ranked in the highest place that was ever attained at others in this country. It was greatly admired by Wedgwood, and was scarcely inferior to the best at Sèvres. The whole contents of the manufactory were sold by auction by M. Sprimont on his retirement; Mr. Duesbury purchasing the house, etc., and the remainder of the stock was sold by Christie and Ansell in 1779.

One of the earliest of the Chelsea marks is here given showing the date; and two anchors side by side and one inverted, in gold, is only found on the finest examples.

The early productions of Chelsea were of soft paste, and the glaze was thick and creamy, much of the white ground being left without decoration. The pieces with the bleu de Vincennes, the peacock green and turquoise blue, copied from the Sèvres ceramists, were of later date. Those of claret-colour are very rare. All these self-coloured examples are highly gilt.

(To be continued.)

By DORA DE BLAQUIÈRE.

Nothing is more curious and interesting in the changes and chances of the world than the stories of things "lost and found." One constantly hears of such on the best authority, being told by people in whom one has the most perfect confidence, and who have no reason to deceive us. Nearly everyone has tales of this kind to tell you when once they understand your interest in the subject, and generally they are about some article of jewelry, and nearly always of finger-rings. I have a large number of notes taken down from people's own lips, some of which would be too strange to be believed if you did not know the character of the narrator. Tales of what we call coincidences, of dreams, of apparitions, all connected with the recovery of certain articles, appear in the collection, but in the following papers I shall try to avoid taxing your powers of belief too severely, for though I may believe what has been related to me, you, not having had my experiences and knowledge of my sources of information, would probably refuse to credit them.

One of the most remarkable tales of rings lost and found is that told of the discovery, in June, 1820, of the signet-ring of Mary, Queen of Scots, in the ruins of the Castle of Fotheringay. The finder was a workman named Robert Wyatt, formerly a private in the Prince of Wales's 3rd Foot. In latter years he gained his living as a guide to the ruins of the castle, and often related to visitors how he assisted in the digging-up of the drawbridge and the filling-up of the moat; and that a Scottish gentleman had measured out the banqueting-hall, where the Queen was executed, and found it correct, and finally, how the ring was found by himself. It is supposed to have been swept away with the blood-stained sawdust, and to have fallen from her finger during the last agonies of her violent death. Wyatt died in September, 1862, at the good age of 83. It has an inscription, i.e., "Henri L. Darnley, 1565," the monogram of H and M bound up in a true lovers' knot, and within the hoop the lion of Scotland on a crowned shield.

This ring was exhibited at the Stuart Exhibition in 1889 (No. 337 in the catalogue), but the description is not quite accurate. It was in the collection of Mr. Waterlow, of Walton Hall, Yorkshire, and a full account is given in the Archæological Journal, vol. xv., p. 253, and also in Archæologia, vol. xxxiii., p. 355. No doubt seems to be entertained that it was Mary's nuptial ring, as well as the betrothal one, the date "1565" being that of their engagement, and they were married the following year.

Mary's rings, indeed, seem to have been addicted to being lost, for I saw at the Peterborough Exhibition, in 1887, a ring lent by Lord Wantage, found in the garden of Sywell Hall, which is believed to have been given by her to one of her attendants there. It has the motto "Tre loyalement ma souvreyn" engraved inside, and is of fine gold. A thumb signet-ring was found at Borthwick Castle, with her cipher on it, "M.R.," and is believed to have been lost during her stay at the castle, to which she fled with Bothwell, 1567. This was at the same exhibition.

Though called a signet-ring, it is well to say here that a signet-ring used by her is now in the British Museum, which was formerly the property of Queen Charlotte, and subsequently belonged to the Duke of York. The betrothal ring, however, is not a signet, though it might have been used for sealing.

Another interesting case of a ring lost and found is that of Dean Bargrave's signet, who was Dean of Canterbury in the days of Cromwell. This ring was probably either lost or hidden in the deanery garden when the dean was seized by Cromwell's Roundheads, and dragged to the Fleet Prison. It was found a few years ago, and was recognised by its appearance in the portrait of the dean, who has it on his finger. The portrait now hangs in the dean's study at Canterbury.

In nearly all the cases I am about to relate, I have the names and addresses of the narrators, and all of them are apparently true, and quite to be relied upon. The first one was told me by the daughter of an old lady, who was the daughter of a clergyman in Essex, and nearly related to one of the Archbishops of Canterbury. She was walking in the garden of the rectory one day, not long before her marriage, when in some way a ring she was wearing slipped from her finger, and no searching availed to recover it. Apparently it was lost for ever. The path was an ordinary gravelled garden walk, and there seemed no place where even so small an object could have found a sheltering to conceal it. The next year, after her marriage, she was paying a visit to her father at the rectory, and was walking down the same path in the garden, when she saw the lost ring lying on the ground in front of her. From the same authority I heard two other stories, the first of a ring lost in a hay-field while the hay-making was going on. After an interval had elapsed of a year and a half, one morning the coachman came in with the lost ring in his hand. He said he had been cutting out hay from the stack, and had felt something hard against the edge of his cleaver, and on putting in his hand, he had immediately discovered the ring. The second story was not of a ring, however, but of a very valuable scarf-pin, lost by a great fox-hunter while riding through a gap in a hedge. The next year the same ground was gone over, and the same gap revisited, which reminded the owner of his lost pin. He dismounted from his horse, and after a short search, found his pin, which was sticking upright in the ground near the hedge.

Many of these modern stories of lost and found sound like repetitions of old ones—"chestnuts," in fact. But they are not; and in this matter, as well as in others of a different kind, history appears to repeat itself. The Canadian story which follows is one of these, but it is quite a new one. It was told me by a friend, and confirmed by her husband, and by the original letter containing the account of the dream, which came from far-off Assiniboinia.

The tale begins with a family who dwelt on a farm by the lake of J—— in Ontario; but finding that the rocky land on its shores was not conducive to successful farming, they moved up to the Great North-West and took up fresh land in Assiniboinia. The family consisted of the father and mother, their son and his wife, and several children, and my tale relates to the son's wife only, who had lost, some years before her departure, in the garden of the old home, her wedding-ring. To a woman it will not be at all wonderful to hear that this loss was a subject of great concern, and also somewhat superstitious fear; for by many people such a loss is thought to be an omen of ill-luck. Some of the family still remained on the lake of J——, a married daughter, the sister-in-law of the loser of the ring. One morning, about two years after the departure of her family, she had a letter from her brother's wife, to beg her to go across the lake to the old homestead, for she had had a very vivid dream about the lost ring; and in this dream she had seen it, lying at the root of a white flower, a phlox, she thought, which grew on the right side of the front door, close to the wall of the house and the door-step.

A few days after the receipt of this letter, Mrs. B—— and her husband rowed across the lake and visited the old farm. It had never been let, and a buyer in those regions is hard to find; so the garden paths were overgrown, and the house neglected and forlorn; but growing by the front door-step there was a white phlox in full bloom, and taking the spade they had brought with them, they dug it up, and at its roots they found the lost wedding-ring.

I also gleaned another story in Canada of the same kind. A worthy alderman of a small town in Ontario was digging potatoes in his garden one summer morning, in the year 1894. His wife had several times summoned him to breakfast, but on her last summons he declared he could not come until he had dug up one more hill. When he finally came in to breakfast he brought with him a ring which she had lost in the garden seven years before, and which he had unearthed in that last potato hill.

A story which I thought very remarkable was told me the other day, and happened, I believe, at Hastings. A maidservant in the family of a resident found a brooch in the street, and as it was both pretty and rather valuable, an advertisement was put into a local paper by the finder, who wished to discover the owner, but without success. Two years elapsed, and the girl and her mistress both agreed that there was no hope of an owner turning up, and so she wore it. The very first day she put it on she went out, and walking down one of the main roads into Hastings, she met a lady who, looking at her closely, said, coming up to her, "I think you are wearing my brooch." The wonderful part of this story is that the lady was only a visitor, and had not been in Hastings since the day she had lost her brooch, two years before.

A writer in the Globe, a short time ago, gave a very remarkable account of a coincidence which is said to have been quite authenticated. A lady finding that the setting of a valuable ring had become insecure, entrusted it to a lad in her service to take it to the jewellers to be repaired. She lived on her estate at a short distance from the neighbouring town, and on his way the messenger had to cross a wooden bridge over a stream in the park. This, of course, presented the usual attraction. The boy lingered, and bethinking him of his charge, took the ring from the case for a closer inspection. But ill-luck followed him, for the ring suddenly slipped from his hold, and falling on a muddy bank, disappeared from view. The lad searched in vain; and being apprehensive that he might be charged with its theft, absconded from his situation and went to sea. Being a quick and handy boy, he grew into an energetic and enterprising man; settled in a colony, and in the course of time realised a large fortune. Returning to England, he found the estate on which he had formerly{29} served was in the market, whereupon he bought it and took up his residence in the Manor House.

Walking through his grounds one day with a friend, they came to the scene of the lost ring, and he related the story which had indirectly led to his present position. "And that is the very spot where it dropped," said he, thrusting his stick into the bank. The lost ring was found upon the stick when it was withdrawn. It had actually impaled the lost jewel, which was its own startling verification of the story. The strange part of this tale is that the loser should have been the finder, for there is nothing marvellous in the misadventure until we come to the finding of the ring.

One of the interesting things shown at the Stuart Exhibition was the keys of Lochleaven Castle. I am sure my readers will all remember the romantic story of Queen Mary's escape from thence in 1568, with the help of young Douglas, who locked the gates to prevent pursuit, and then threw the keys into the lake, where they lay until discovered in 1805.

Many people have looked at the dredging and cleansing of the Tiber, which has been going on for the last few years, with much interest, in the hope that, during the course of these labours, many precious objects would be discovered, and amongst others, the spoils of the Temple at Jerusalem, which were brought by Titus to grace his triumph, and which may be seen depicted on the inside of the arch erected to commemorate his victories. Amongst these were the seven-branched candlesticks and the table of the shewbread. These, with other treasures, are said to have been thrown into the Tiber.

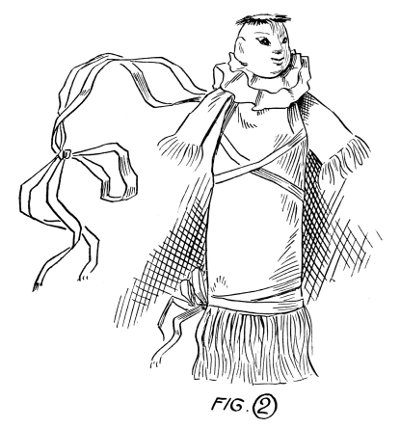

One of these little ladies travelled safely all the way from Ohio, United States, wrapped up in a newspaper; her sister came only from the other side of London, and arrived with a smashed head. Two kind friends, knowing I am always on the look-out for some novelty for "Our Girls," were seized simultaneously with the desire, which they carried into effect, to send me an "idea" by way of a birthday present, and here is the result.

The wee "Jap" dolls may be bought for a penny each at many fancy shops. For Fig. 1, three-quarters of a yard of satin or any good ribbon three inches wide, and one yard of a contrasting colour an inch wide, is required. Double the piece of wide ribbon and fringe both ends for an inch and a half, oversew one side, insert a thick layer of wadding to within two inches of the top, plentifully besprinkled with sweet sachet-powder—obtainable at any chemist's—oversew the otherside and along the bottom above the fringe, cut a hole at the top sufficiently large to insert the doll's body—poor thing, she requires no legs—fix it firmly at shoulders and waist, take the narrow ribbon and drape it gracefully round according to the drawing, leaving a loop for hanging purposes. Fig. 2 requires but half a yard of wide ribbon, two yards of quarter-inch ditto, and half a yard of one inch wide. Two little sleeves are made of the wide ribbon folded lengthwise and fringed at one end; the remainder is folded, filled, and sewn up. In this case only the doll's head is retained; there are no arms within those sleeves as in Fig. 1. A "toby" frill is made with the half yard of inch-wide ribbon, and the narrow is arranged artistically according to Fig. 2.

It is quite possible, of course, to make these sachets with any odds and ends of silk without buying special pieces of any particular width. The little dolls and some sachet-powder are the only absolute necessaries, and, if good colourings are chosen, an array of them look most tempting and fascinating on a bazaar stall. They should not be sold for less than sixpence, and in some places might fetch a shilling.

"Cousin Lil."

The Temple.

My dear Dorothy.—You do not often favour me with your correspondence, so that I was particularly pleased and flattered by the receipt of your letter asking for my opinion, as a rising barrister, on the following important legal points, which I will now proceed to deal with. As you have approached me without the intervention of a solicitor, it may possibly gratify you to know that I am not entitled to make any charge (even were I disposed to do so) for my professional opinions. This statement will, I am sure, remove a great weight from your mind; but a truce to jesting, now to business.

In your first question you ask me to decide whether you or Mr. Anstruther were right on the question of paying excess fares on your return from the Crystal Palace the other evening.

So far as the arguments adduced on either side are concerned, I can tell you frankly that you were both wrong; but let me have the facts of the case clearly stated before me. It appears that Aunt Anne, Robert and yourself went down last Wednesday to the Crystal Palace, where you met Miss Anstruther and her brother; and I have no doubt enjoyed yourselves immensely, wandering through those lovely grounds, gazing at the antediluvian monsters on the lakes or listening to the bands in the rosary or on the terrace.

In my opinion the Crystal Palace is just the place to spend a happy day. This, however, is a digression.

Instead of dining at the Palace, Aunt Anne invited the Anstruthers to return to town with you and to take their chance of getting—what I from personal experience can vouch for as certain to have been—an excellent impromptu meal.

On the return journey—we are getting to the point at last—the tickets were collected at Battersea Bridge, your tickets were returns to Victoria, but the Anstruthers had returns to Clapham Junction only, and accordingly Mr. Anstruther was invited to pay excess fare on them.

As a matter of fact the price for a return ticket from Victoria to the Palace is exactly the same as a return from Clapham Junction to the Palace, and such being the case, you considered that the collector had no right to demand an excess fare on Mr. Anstruther's tickets. You were wrong. Mr. Anstruther, you say, paid the excess on the ground that it was merely a concession on the part of the Company to those booking at Victoria to charge them the same fare as those booking at Clapham Junction; this may or may not be the case, it is beside the question.

The matter is entirely one of contract between yourself and the Railway Company. They contract to carry you for a certain sum to a certain place; in your case it was from Victoria to the Palace and back, and in the case of Mr. Anstruther and his sister from Clapham Junction to the Palace and back. On their return, therefore, to Clapham Junction, the contract between themselves and the Railway Company was completed, and on their remaining in the train and travelling up to Victoria a new contract was commenced between themselves and the Company. Mr. Anstruther was right, therefore, in paying the excess demanded, although his reason for doing so was not the right one.

To turn to quite another matter, I see that you want my advice on a point in connection with bicycles. So you also have not escaped the cycling craze of the day. Oh, Dorothy, after this I shall not be surprised to hear that you have taken to golf!

I am very sorry that you should have been annoyed by the insolence of the cabman; I am afraid our London jehus are not called "growlers" without reason, and some of them are only too ready to take advantage of ladies, when travelling without male escort, to insult them with impunity.