Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 1895. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 839. | two dollars a year. |

"An hour's sport with a Spanish cruiser—that's what it will be," Benito Bastian said to himself.

But the care he was giving to his boat looked like more serious business than an hour's sport. She is a swift sharpie that he called Villa Clara, after his native town, and she was drawn up on the beach and turned over, and Benito was scraping her clean. If she ever did fast sailing, he wanted her to do it that night.

"Let this wind hold, and give me a dark night," he went on, "and it will take a faster cruiser than El Rey to catch me."

Benito is a handsome dark-eyed Cuban boy, who lives on the little Cuban island called Ginger Key, forty miles north of the Cuban coast. The boys of Ginger Key, like their older brothers, are full of excitement just now; for occasionally a band of Cuban patriots makes its way over from Florida and goes into hiding in the thick woods, and watches its chance to land on the coast of Cuba. These hands need guides; and it is the Ginger Key boys who know the waters well, and the coast too. Benito handles his sharpie to perfection on the darkest nights and in all kinds of weather; and as to helping his countrymen, the Cuban insurgents, he feels about it just as the Boston boys felt about Bunker Hill.

"I ought to be doing something for the cause," he said to himself several months ago. "It's a pity I'm only sixteen; they may think I am too young. But I know these waters as well as any man on the key."

He looked down regretfully at his bare feet and legs, for his trousers were rolled well up. He took off his old straw hat and smiled at it; but he could not see how his brown eyes flashed, nor how handsome his brown hair looked, waving in the wind. He is tall and strong for his age, and brown as a berry—not only from the sun, but by nature.

"Yes, they'll say I'm only a boy, that's sure," he continued; "so I must have my wits about me if I want to get a chance."

Two large parties of armed men Benito saw land on Ginger Key, and saw neighbors of his pilot them across to Cuba, dodging the Spanish cruisers. Then a third party came and went into camp, while the schooner Dart cruised up and down in the Florida straits. This last party staid so long that something seemed to be wrong, and Benito made up his mind that he might be useful; at any rate, he would try. He said little, but learned all he could, and when the opportunity came he went to the leader of the party.

"You don't get away very fast," he said to the leader, taking care to speak in a low voice. "It's ticklish work, landing men near Sagua la Grande. That's well watched."

The man looked at him curiously, surprised that this boy should know so much about his arrangements.

"Yes," he answered, "that is well watched. El Rey, the big Spanish cruiser, patrols that coast day and night."

"I think I could draw her off long enough for you to land your men," Benito whispered.

"You?" the man exclaimed; "why, you are only a boy!" It was just as Benito expected.

He went on to unfold the plan he had made; and it was a plan so full of daring and danger that the man opened his eyes wide.

"Well," said he, "you're full of grit, if you are only a boy. But you are very young, and I don't know anything about you. I don't even know whether you could make your way over to Cuba. You run over there alone and bring me some token to show that you've been there, and then I will talk to you."

"That's easy," Benito answered. "What shall I bring you?"

The man thought a moment. "Bring me a bunch of red bananas," he answered. "They are plenty in Cuba, but you raise only yellow ones on this key. If you bring me a bunch of red bananas, I will know that you have been in Cuba."

Forty-eight hours later Benito laid a bunch of red bananas in the leader's tent, and gave him some valuable information about the movements of the cruiser.

"I think you'll do," said the man. "You are not all talk and no action, like some of these fellows. If you can draw the cruiser off and keep her out of our way for two hours, you are worthy to call yourself a Cuban."

"Very good," Benito answered. "I will try."

They talked over the details of the plan, and agreed that they must wait for a pitch-dark night and a brisk wind. On the morning that Benito scraped his boat, there was every promise of such a night. There would be no moon, the sky was overcast, and a lively breeze came in from the southeast.

Seventy-five men and a great many cases of rifles were on board the schooner Dart, at five o'clock that afternoon, the hour agreed upon for sailing to make sure of reaching Sagua la Grande by midnight; and the sharpie Villa Clara seemed impatient for Benito to hoist her sails.

"We will give you a line and tow you over," said the leader.

"Oh, I guess you don't know the Villa Clara," Benito answered. "I think she will show the schooner the way."

"One thing I must ask you," were the leader's last words before he went on board the schooner—"do your father and mother know what danger you are going into to-night?"

"I have no father or mother," Benito replied, sadly; "so if I don't come back it will not make much difference."

None knew better than he the risk he was taking. The cruiser would blow him out of the water if she could; and if any of them were captured, they would either be shot or be sentenced by the Spaniards to long terms of imprisonment.

The night was all they could ask, and just what they had waited for. No moon, the sky full of black clouds to obscure the stars, and half a gale blowing from the southeast. Benito was willing to risk his life on the sharpie being a faster boat than the Spanish cruiser on such a night.

Neither schooner nor sharpie showed a light; and if Benito had been captured on the way over his captors would have been astonished at the cargo he carried. In the bottom of his boat were a dozen boards, each two feet long by a foot wide, with a shallow tin can nailed to the middle of each board. And there were four canisters of colored fire—one red, one yellow, one green, and one white. And there were several yards of fuse, and a box of sand. The colored fire and the fuse Benito had bought when he visited Cuba for the bananas.

"The schooner is to lie to as soon as we sight the lights on the Cuban coast," was the arrangement Benito made with the leader. "After I find the cruiser you will see her lights moving; but she will be nearer to me than to you. I will give you a white light when all is safe. When I burn a white light you can land your men."

The sharpie and the schooner kept well together till they were near the coast of Cuba, and they saw the lights of Sagua la Grande before ten o'clock. This was so much earlier than they had expected that it made some difference in Benito's plans. By midnight the cruiser, following her usual course, should be somewhere off Cardenas; but instead of that they saw her lights directly in front of the spot where they proposed to land the men.

"So much the better," said Benito, when he boarded the schooner for a moment before setting his dangerous plot in motion. "I will coax her down to the eastward."

The leader of the party gave him a warm grip of the hand before they parted.

"You are a brave lad," said he. "When you are under the cruiser's fire, remember that it is in the cause of freedom."

"Oh, I don't think they can hit me," Benito answered; "and I am sure they can't catch me." And he was off.

The schooner and the sharpie had this great advantage; they could see the cruiser's lights, but she could not see them.

Benito beat down the coast till he was about five miles to the eastward of the cruiser, and several miles from the shore. Then he took up one of his boards with the shallow tin can nailed to it.

He poured sand into the can till it was about two-thirds full, and then put in a good inch of red fire. Through a little hole that he had punched in the side of the can he inserted the end of a full half-yard of fuse, and wound it round and round the can, and tied it with a cord to keep it out of the water. Cautiously he struck a match under the stern seat and touched it to the fuse, and laid the board on the surface of the water and left it floating there.

This done, he headed the sharpie for shore. The long fuse was used because he desired to be close under the shore before the red fire burned. The southeast wind was just right for him, and the sharpie fairly flew through the water. He was close enough in, and was pouring sand into the second can fastened to a board, when the red light blazed up.

What a glare it made! Certainly that lurid light must be visible for twenty miles.

It was green fire that Benito poured into his second can, and for this he used a much shorter fuse—just long enough to give him time to escape from the circle of light that was sure to follow. The red fire had hardly died out before the green fire blazed up, but by that time Benito was half a mile away.

"That will stir them up," he said to himself. The sharpie was making a long run to the northeast then, seaward and away from the cruiser; but he kept an eye on her lights. "It's plain enough what that means. First the red light, a signal from a party about to land; then the green light, an answering signal from their friends on shore. At least that's what I want the cruiser to think, and I believe she will; and she'll hunt those lights."

"Ah!" he exclaimed, a moment later, "the cruiser has seen the lights, for she's moving. I've started her, sure. Now the excitement begins."

The cruiser's lights grew larger and larger. She was standing down the coast, almost straight toward the green light, which still burned. She ran up within a half-mile of it, and fire belched from one of her turrets.

C-r-a-s-h! crash! Not one great boom, but a continuous roar.

"That's her Gatling!" Benito exclaimed. "Lucky I didn't burn my lights on the boat, as I thought of doing."

Spain's cruisers are as modern as our American vessels, and fitted with every deadly appliance. The one thing that El Rey lacks is a search-light; if she had carried a search-light that night Benito would not be alive to tell this story.

The green light disappeared under the shower of bullets, and the cruiser kept on her course. That was against the wind, and the sharpie could not compete with steam against the wind; but Benito was heading out seaward, off to the northeast, further and further away from the schooner.

When he was full three miles out from shore again, and perhaps eight miles from the Dart, he set off another red light, giving it, as before, a long fuse. He was hardly fifty feet away from it when there came another crash from the[Pg 79] cruiser—a deep boom this time from one of her heavy guns, followed by a shower of bullets from the Gatling; he heard them whistling and shrieking through the air, but he was not struck. The red light had not even begun to burn yet; the cruiser's watchful men had seen the spark burning at the end of the fuse.

"All right, Spaniard!" Benito exclaimed. He had never been under fire before, and his lips were set firm, and his free hand involuntarily closed into a tight fist. "All right, Spaniard! I've got you waked up, anyhow. You're chasing a party of insurgents, ain't you! I wish I dared tell you that you're chasing a boy, while the insurgents are getting ready to land ten miles up the coast!"

He stood in for the shore again, still beating to the eastward as close as the wind would allow; and when the fuse's spark blazed up into a bright red light the cruiser was heading towards it.

"A little careful about showing this light; that's what I'll have to be; a little careful," he said to himself, as he struck a match to set off his second green light close to shore. He kept the sharpie between the spark of fuse and the cutter's lights as long as he could to hide the fire, and then stood out seaward to the northeast again.

As the green light blazed up he turned his head a moment to look at it, and in that instant a strange thing happened. When he looked towards the cruiser again she had disappeared! Save for the green fire burning there was not a spark of light on all that black sea.

"I thought she'd do that!" Benito exclaimed. "She's trying my own game, and has put out all her lights. Well, I'll give her a white light in a few minutes, and that will be something new for her to think about."

He was still running out seaward and eastward, and the sharpie was bending down to her work, and cutting the waves like a knife, when suddenly he heard the throbbing of an engine and the splash of a propeller. Before he had time to think a great black wall of iron, looming twenty feet above his head, was right on top of him.

The cruiser was accidentally running him down in the darkness! He could see nothing on the water, but there was light enough in the sky to make out her great black form towering over him. His first impulse was to cry out; but he shut his teeth tight and waited for the blow.

But the blow did not come. The next instant the black mass was shooting past him, her iron side hardly six feet from the sharpie's stern.

"Good sharpie! Good old girl!" he exclaimed; and in the excitement he patted the boat on the gunwale. "If you hadn't been a flier, we'd been goners that time."

Benito's heart was in his throat for a few minutes; he would not pretend to deny that. But no wonder, for no boat ever had a narrower escape. He ran out several miles more and burned his white light, which said to the schooner:

"Land your men! I have the cruiser busy." And then he ran out five miles further to the northeast and burned another red light.

"That's an extra touch, that last red light," he said to himself. "They gave me a close rub, so I'll just mix them up a little worse."

Then he put the sharpie about, and headed her for Ginger Key. He had risked his little all—his life and his boat—in the cause of his country, and his night's work was done. With the wind on his starboard quarter he knew that no cruiser in Cuban waters could overtake him. Before he had gone far he saw lights on the cruiser again, and they showed her to be nearly where he had burned the white fire, fully ten miles from the schooner. And by that time the men were all on shore.

Next day Benito was on Ginger Key as usual; but it was not till nearly a month later that a passing schooner carried to the key a letter with an Havana postmark, addressed to Benito Bastian. The letter was only a few lines, without any signature; but it enclosed a Spanish draft for two hundred dollars.

"We landed safely, and are with friends," the letter said. "We have made up this little testimonial for a brave boy we know."

The next morning Cato was sent over to the Hewes' mansion with a note signed by both the twins, and addressed to Carter. It requested him to come to Stanham Manor and spend the day, and plans were laid to have a glorious time.

But what was their disappointment when Cato brought back the news that their new-found friend and old-time enemy had left that very morning with his father for New York.

The twins were much cast down, but there was soon to be a greater burden on their minds, for after luncheon they had been told that a parting would shortly take place between them, and that Mr. Daniel Frothingham was going to take William back with him to England.

For some reason Uncle Nathan had a marked partiality for William, but he was the last person in the world to have held a preference in this regard, as it was absolutely impossible for Uncle Nathan to tell the twins apart.

The boys had listened to the news of the coming separation in dignified silence, and as soon as possible they had made their way back to the garden behind the house. Their feelings at first were too deep for words.

"I will not go, unless you go too," said the elder boy at last, seating himself on the edge of a grass-plot. He had hard work to keep from crying.

"You said you wanted to go to England," said George. "You have talked about it often."

"Well, it's not fair," said William. "Why should he choose me?"

"It may not be for long," answered George. "You'll come back—or probably I can go over there to see you."

"And we may be able to get into the army," said William, trying to be cheerful.

George sat down beside him. "I do wish I were leaving with you," he said, choking back the tears, "but he refused to think of sending us both. Aunt Clarissa asked him." He put his arm about his brother's shoulders. "I'm going to be sent to town to school," he added.

"I tell you what let's do," said William. "Let's draw lots, and see which one of us will go to London."

He broke a bundle of spears of grass and tore them off, some longer than others. Then he rubbed two of them in his hands.

"I don't know which it is," he said; "but if you get the shorter one, you go, and if you get the longer one, I go."

George drew at once. It was the shorter spear. So far as Uncle Nathan's preference went, it counted for nothing with his nephews.

The departure that took place the following week was an affair of the greatest moment. Although the young Frothinghams did not know it at the time, it was a long farewell they were taking of Stanham Mills.

Good-byes were said at last, and, to tell the truth, tears were shed in plenty as they parted from their sister.

The twins' belongings were packed into small boxes, then the old chaise was harnessed up, and seated beside their Uncle Daniel, and followed by Nathaniel Frothingham and Cato on horseback, they set out to make the long journey to the city. Mr. Wyeth had started the previous afternoon.

The young Frothinghams had been to New York only once before, when they were very small indeed, and their recollections of the first visit were somewhat vague.

It was long after dusk when the little party arrived at their destination. They had been rowed across the river from Paulus Hook, and went with their uncle at once to a tavern which in the days of Dutch supremacy had been one of New York's most aristocratic dwelling-houses. Now it[Pg 80] was the rendezvous for merchants of Tory principles and army officers. Young, befrilled, and powdered dandies who aped the manners of the Continent hero exchanged their pinches of snuff with as much gallantry and courtesy as if they had met at the palace of St. James.

The Stanham party had been driven from the ferry in a rough lumbering affair—half coach, half omnibus—and had been deposited with their small box and the saddle-bags at the door of the tavern.

As they had gone down the hallway they caught a glimpse, through the open door on the right, of a group of men in red coats, with much glitter of gold lace and many buttons, who could be seen through the thick clouds of tobacco smoke seated about a large steaming punch-bowl on a great oak table. They were some of the officers of his Majesty's forces that had been sent to "protect" the inhabitants of his "thankless colonies."

Everything was new to the boys—the sound of the many voices, the snatches of songs and choruses that now and then came up from the coffee-room, the jingle of spurs and sabres as a party of troopers made their way across the stone flagging of the court. In all directions were delights, and in their little room they could hardly sleep from excitement that first night.

Early in the morning they looked out of the window, still thrilled with the pleasure that all young natures feel at being amidst new surroundings. It was a beautiful day, and the wind blowing from the southward was filled with the fresh smell of the sea. Their room was high up, and they could look over the sloping roofs and house-tops across the river and out into the bay, where two or three huge men-of-war lay straining at their anchors.

"Isn't it fine!" exclaimed William, as they knelt on the floor with both elbows on the window-sill, drawing short breaths with gasps of sheer delight.

At the end of the street was a small green, and here a company of infantry was drilling. They could catch the glint of the sunlight upon the muskets, and almost hear the energetic words of the young officer, who strode up and down the front.

"Oh, to be a soldier!" said William.

"Wouldn't it be grand?" said George, the martial spirit that animates almost every boy welling up in him so strongly that he quivered from the top of his head to the soles of his bare feet.

Just then a two-horse equipage was seen coming down the street, with the dust flying up from the great red wheels. In it sat a man, richly dressed, with his three-cornered hat set sideways over his powdered hair, his chin resting on his hands, which were supported by a gold-headed cane, and a sneer was upon the cruel lips.

It was Governor Tryon, who had put down the so-called "rebellion" in the Carolinas, and for his "fidelity" in hanging several people who strongly expressed their views had been honored by the post of being his Majesty's representative, the Governor at New York.

The boys were craning their necks to get a good view of the red-wheeled coach, when suddenly there was a knock on the door. It was old Cato.

"Come on, young gentlemen," he said. "Hurry on yo' close; yo' uncles is waitin' breakfast down below stairs."

They jumped up, and in a few minutes were both arrayed in the quaint costumes in which we first saw them. True, the pink breeches, despite Aunt Polly's careful ironing, showed traces of the plunge into the brook, and the buttons on the heavy velvet coats were not all mates; but Aunt Clarissa had sacrificed some of her treasures, and the lace trimmings were fresh and clean.

"I wish we had swords," said George, thinking of the glimpse of a young periwigged dandy he had seen talking to some ladies in the tavern parlor the night before.

The two uncles greeted the twins quite cheerfully. The ship that was going to take Uncle Daniel back to England was to sail early on the morrow, and he appeared glad indeed at the prospect of leaving America behind him. As the boys sat down, Mr. Wyeth came up and joined the party.

"Well, my young gentlemen," he said, bowing over the back of his chair, "we're glad to see you in the city; and what do you think of it?" he inquired.

"It's very fine," ventured George, but then he could say no more. He grasped his brother's hand underneath the table. He could not speak of the prospect of leaving William then, for, of course, no one else knew that the twins had decided in their own way which one was to go with Uncle Daniel.

A party of officers in all the bravery of their red coats and glittering accoutrements came laughing through the doorway. They hardly acknowledged Mr. Wyeth's salute, and seated themselves at a table, thumping loudly with their fists, and calling for the waiter.

The twins looked at them in wide-eyed admiration.

"This is a loyal house," said Mr. Wyeth, with a sigh of pleasure. "But I do assure you, sir," addressing Uncle Daniel, "that there are other taverns in the town where seditious speeches are made openly, and where men gather whose conduct and whose thoughts approach almost to open rebellion." He lowered his voice. "The merchants here have followed the pernicious example of the misguided Bostonians, and have refused to import English goods. If this keeps up, ruin to the country must follow. Secret societies have been formed, and their abominable proclamations can be seen posted on almost every corner. They say England has no right to impose a tax of any kind."

Uncle Nathan frowned, but he restrained his tendency to burst into rage. "There are the gentlemen who can take care of the rebels," he said, nodding towards the group of officers. "The prisons should be filled with malcontents, who dare to dispute the authority of the King." Uncle Nathan had calmed himself with an extreme effort.

After breakfast the boys set out for a stroll, and made their way down to the Battery. As they turned into the little park whom should they see but Carter Hewes leaning against a big stone post, and watching the waters lapping against the sea-wall.

"Carter!" they both shouted, running forward, and some breathless greetings were exchanged.

"What brings you here?" said one of the twins at last, after they had explained their own presence and their mission.

"I came with my father," said Carter. Then he lowered his voice. "He is here on business, you see."

Just then what Carter was going to say was drowned by the sudden rolling of a drum, and down Broadway, into which the boys had turned, came a company of English foot.

"Don't they look splendid?" said William, keeping time to the throbbing of the music.

Carter looked at them sullenly. "They may have a chance to lose some of their finery soon," he said. "I wish they were at the bottom of the sea. If some people were not blind they would have been sent back before—back where they came from!"

"But the King," said William, pointing to the small bronze statue of George III. on horseback, that was in the little circle on the near-by Bowling Green.

"Confound the King!" said Carter. "He's the blindest of them all."

This expression must be pardoned on account of Carter's youth. Probably even his hot-headed father would not have used it in such a public place at least.

The twins gasped and stepped back slowly from him. "You are a rebel, then!" they both said, and, turning, they walked away, without looking over their shoulders.

Carter remained standing where he was. He saw he had offended the loyal young Frothinghams beyond manner of expression, and he wished that he could take back his words, now that it was too late.

But the twins walked silently along; they felt each other's minds so well that speech was not needed. However, when they had gone some distance up Broadway they stopped for a moment before a house where some troops were quartered, for a drum rested on the doorstep.

A tall soldier stepped outside of the house. He was putting pipeclay on his white cross-belts, and smoking[Pg 81] some villanous tobacco, which caused him to hold his head to one side to keep the smoke from getting in his eyes. He was humming a bit of song as he worked, and suddenly glancing down, his eye caught the boys watching him.

"Git out, ye little Yankee rebels!" he said, and launched a kick in their direction—"git out of this."

"We are not 'Yankee rebels,'" said the younger, drawing himself up proudly.

"We are loyal subjects of his Majesty King George," said William, "and you have no right to talk to any one like that, no matter who they are!"

The man paused and took the pipe out of his mouth. "Tare and ages!" he said, "an' you're loyal subjects of the King, in troth?"

"We would fight for him," said William.

"Hear the bhoys!" said the man. Then he called back through the doorway, "Shaughnessy," said he, "come out here quick; here are two recruities fer ye!"

Another tall man with sergeant's chevrons on his sleeves came to the doorway. The powder from his hair was still about his shoulders, and he was binding his queue with a black cord, holding the end of it in his mouth, and twisting the cord around and around until he deftly tied it with a jerk. Then he spoke over his companion's shoulders.

"Would yez enlist?" he said.

"If we were old enough," said William.

"Ah, they're brave lads," said the first speaker. "If there was more like thim I could go back to my Katherine at Bally Connor, and now we'll be kipt here until the saints only know whin, and probably will have to fight out in the howlin' wilderness."

"Come down and see us, bhoys," broke in the second speaker. Then he whispered, "Bring some of yer father's terbaccy, or a paper o' snuff. How's that, Gineral McCune?"

"Or a bottle of somethin' warmin'," suggested the other one.

The twins were too much depressed by the result of their meeting with Carter to appear amused. They simply turned and walked away, and after a stroll of an hour or so they arrived at Smith's Tavern again.

The hours passed quickly. At next sunrise the boys were dressing in their little room at the top of the house. William handed a coat to George. It was the one Aunt Clarissa had prepared for the journey.

Generally the old lady had endeavored to make some slight differences in the boys' garments, which was not noticeable at first glance, but was helpful in distinguishing them, provided each wore his own apparel.

George put on William's coat, but paused, with his arm half-way in the sleeve. "No, William, you ought to go," he said.

"Pray, it's settled," replied his brother. "When they find it out perhaps they will send me too."

"How about the scar?" said George, reading his brother's thoughts.

William made a sudden movement and extended his arm. Across the back of his left hand ran a large scar. He had hurt it years ago while playing with a sickle out at Stanham Mills. It showed quite plainly in a good strong light.

"Perhaps you had better go, after all," said George.

"Not a single step," replied his brother. "You know we never change when we once have drawn lots. I can keep my hand hidden easily enough. Besides, they have not thought of looking for a long time now."

This decided it, and with the exchange of coats the boys exchanged their names, as they had done on various occasions before.

All was bustle and confusion at the wharf where the Abel Trader lay.

Cato stood by trying hard to smile, but the tears were running down his cheeks and dropping from the point of his grizzled chin.

The tide and wind were ripe to swing the vessel out from shore; the last good-byes had been said. George was standing[Pg 82] by Uncle Daniel on the deck. For some few minutes the twins had not been able to speak a word, for they would have cried hysterically, and they knew it well enough.

Suddenly William drew his hand across his eyes; Uncle Nathan started. There was the red scar!

The gang-plank was being drawn, and the old man staggered. "Stop there a minute!" he shouted, before the last cable was thrown off. "Stop there, I say!"

He rushed up the swaying plank to the deck, holding William by the arm, and fairly dragging him after him.

"You little villains!" he exclaimed, hoarsely, as he pushed up to where his brother Daniel and George were standing near the taffrail. He exchanged the boys much as one person would take one article in place of another, and did not even have time to reply to Uncle Daniel's astonished exclamation, but holding George as if he were afraid he would soar into the air, and with a grasp that made the boy wince with pain, he muttered beneath his breath, and fairly had to make a jump for it to regain the dock.

Once there, Uncle Nathan began to shake the boy so fiercely that his head almost flew off his shoulders.

The little brig swung slowly out, and her blocks grated as her yards were braced around. Then her jibs clattered up the forestays and she caught the wind.

Strange to say, if it had not been for Uncle Nathan's action on this day this story might never have been written.

It was a rainy April day in New York. Three years had passed since the events of the last chapter. Promises of spring were to be seen on every hand. A few warm days had already started the leaf buds along the Bowery Lane; even a few blossoms had begun to show in the shrubbery in Ranleigh Gardens.

But the feeling of uneasiness in the colonies, due to the continued oppressions of Great Britain, was soon to be broken by a burst of flame.

New York was yet the most loyal city that the King held in America, but much indignation had been shown at the actions of the crown that were directed against Boston, and the latter city was on the verge of rebellion. Except for the excitement of the days when the long-expected tea was attempted to be landed in New York in April, when Captain Lockyer had returned to England with the tea-ships, their cargoes all intact, the year of '74 had passed without happenings of much moment.

But now it was the momentous year of '75, and many things had changed—changes in some respects hard to believe.

Poring over the books in a dingy shipping-office in a narrow side street off Mill Lane leaned a tall figure. Two years of this same kind of work had not impaired George's health in the least. Although now only sixteen, he looked years older, for he was tall and wonderfully developed, and the grave manner of speech and that strange dignity which the young Frothinghams possessed had not left him. From some ancestor the twins must have inherited immense natural strength, for George was as strong almost as the biggest porter in Mr. Wyeth's employ.

His clothes were neat, but were devoid of any attempt at lace or ornament. In fact, young Frothingham had quite a struggle at present to get along. His aunt sent him a little money from the proceeds of the grist-mill, for mining had now wholly ceased at Stanham Mills. This, with the pittance that Mr. Wyeth paid him for his services, had enabled him to secure a small room in the house of a good old Irish woman named Mrs. Mack, who washed clothes for the gentle folk.

Poor Uncle Nathan had been dead now two years or more, and George had been taken from school at a Mr. Anderson's, and placed in Mr. Wyeth's office.

Mr. Wyeth and George had grown apart in the last year. The latter always did his duty, but could not stand the tirades of the virulent Tory against a cause to which the boy now felt himself firmly united, for George, even against his will and inclination, had become converted to the side taken by the Sons of Liberty. Mr. Wyeth, over a year before this rainy April morning, had found that George had, as he expressed it, "gone entirely wrong," and after seeing remonstrance would be in vain, had ignored him altogether. If it were not for what he owed Uncle Daniel in London he would have discharged him from his service.

This would not have mattered much. But there was one sorrow that cut the younger Frothingham deeper and deeper every day. It was the tone of his brother's letters from England. Since the day upon the dock they had not seen each other. Long letters, however, passed between them every month.

So strongly had William felt upon the matter, and so frequently had he expressed himself angrily at the course of popular thought and action in the colonies, that George could never bring himself to take up the other side in his correspondence. There had never been a difference of opinion between them in their lives. So he had from the first ignored the question in his letters to his brother.

If, however, the trouble should blow over, and wise counsels prevail in England, at some future time, when everything was once more tranquil, he could confess all. England even at this late moment could have recalled the colonies to her standard.

In the mean time, no one, not even Mr. Wyeth or his fellow clerks, knew that George was attached to a secret society, whose members were pledged to give their lives to "opposing tyranny."

George was not the only lad whose smooth face was innocent of a razor, but whose strong young frame and true heart were both at the service of his country.

Through the window-panes of Mr. Wyeth's office, on the second floor, could be seen the dripping streets and the rain pouring down from the gables of the houses.

George paused, with his finger marking the place in a column of figures, and looked out. He saw Mr. Wyeth coming towards the office, and as soon as he had entered, the merchant came through the large store-room and approached George's desk.

"Master Frothingham," he said, "will you come to my house to-morrow morning? I am desirous of having people in my employ meet some gentlemen who will be there present."

George accepted the invitation gravely, and the events of the next day were to have a tremendous influence on his life.

The morrow dawned clear and bright. It was Sunday, the twenty-second of the month. Clouds, however, were banking all around, and shortly after the breakfast hour it was portending rain.

George walked to his employer's house. Several of his fellow clerks waited in the hall. Mr. Wyeth was in consultation in his library with one or two influential men of well-known royalist principles. One of them was Rivington the Tory, printer to his Majesty, and another was Mr. Anderson, George's former schoolmaster, now secretary to the hated Governor Tryon.

The bells had commenced ringing for church, and people could be seen walking along the streets with their prayer-books under one arm and unwieldy umbrellas under the other.

"We are going to receive a lecture on loyalty to the crown," whispered one of the clerks.

"I do not think we are in need of it, Master Frothingham," said another. "Trust us for that."

The speaker was a loose-jointed youth, with pale fishy eyes, whom George disliked extremely. So he did not reply, but walked to the doorway and gazed out through the little strip of lozenge-shaped windows. It had commenced to rain, and the big drops were hopping up from the doorstep.

The street joined the Bowery Lane; the ground sloped slightly, and at the top of the incline the lad saw a crowd was gathering. Some people bareheaded, others with umbrellas, were swarming out from the houses and thronging at the corner. The church-going crowds had halted.

There was a man on horseback there, who waved his[Pg 83] hand excitedly as he talked. News had evidently come from Boston, and all ran to the window. What could it mean? Just then some one laughed. Flying down the hill came Abel Norton, the chief clerk. He was plashing the mud to right and left, and holding his hat on with both hands as he ran along, heading direct for Mr. Wyeth's.

"Abel's got the news," said some one. "There's no use going out; we'll hear it all." They laughed again.

The old man burst breathlessly through the door, and at that moment a cheer came from the crowd outside. The people did not seem to mind the rain in the least. Hats were thrown into the air, then the gathering dispersed in different directions, and the corner was deserted.

Abel stood leaning against the tall clock in the hallway, trying to catch his breath.

"Where's Mr. Wyeth?" he said.

The latter, hearing the disturbance, had pushed himself out of the great leather chair in his library, and had stepped to the door.

"Did any one call my name?" he asked; then catching sight of Abel's dripping figure, "Well, sir," he said, "what means this, prithee?"

"It means," said Abel, "that there has been a battle near Boston. It means that war is on."

"Another Tea Party, I presume," said Mr. Wyeth, taking a pinch of snuff calmly, and dusting his shirt frill with a stroke of his fingers.

"No, sir," exclaimed the chief clerk. "His Majesty's troops have been defeated, and driven, with great slaughter, back from Concord and Lexington to the protection of the city. The rebels are organized, well drilled and armed."

"Hurrah!" said a voice quite audibly.

Everybody started back in consternation; Mr. Wyeth dropped his snuff-box with a jingle.

"Who said that?" he asked, his face turning a shade redder.

George stepped forward. He was pale, and his hands were gripped strongly together behind his back.

"THE TIME HAS COME," HE SAID, LOOKING MR. WYETH IN THE

EYE.

"THE TIME HAS COME," HE SAID, LOOKING MR. WYETH IN THE

EYE.

"The time has come," he said, looking Mr. Wyeth in the eye—"the time to decide. I did so long ago. The voice of liberty has spoken."

There was a murmur of assent or disagreement—it was hard to tell which—from the group of clerks.

One of the porters who stood in the doorway with folded arms exclaimed, beneath his breath, so no one heard him, "Thank God!"

Mr. Wyeth stepped forward. "I had suspected quite as much," he said. "You disgrace your name, sir. Leave my presence and eke my employment. Instanter, sir."

George walked down the hall. When he reached the door, he turned and bowed.

"Hold!" exclaimed Mr. Wyeth. "There is a letter here from your brother in England. Let us trust that he is more loyal to his country's interests and to his King. Let us trust that there is only one of your family name who does not know his duty."

He extended a letter which had arrived by a packet the previous afternoon. George took it and silently walked out into the rain.

The porter Thomas followed him and half closed the door behind him. "I thank you, Mr. Frothingham," he said, "for the words you spoke. We'll drive the 'Lobster Backs' into the ships, and turn 'em all adrift—eh, sir, will we not?"

The two grasped hands without a word, and George, stepping into the shelter of a big elm, broke the seal of the letter.

It was from William. It beseeched him to stand by the side of the "loyal men and true, who uphold the crown." It expressed sorrow at hearing through Mr. Wyeth that he had been seen at least on friendly terms with "traitors and arch conspirators." His brother prayed him to remember all their early talks, and exhorted that his first thought be of the King.

"If you cannot answer me," went on the letter, "in a way I hope you will, I shall understand your silence; but remember it is for the—"

George glanced at the last word, crumpled the letter in his hands, and then tore it into small pieces that floated out into the rainy gutter.

"My country has no King now," he said, and looking out through the rain and through his tears it seemed to him that the world was turned upside down. He drew his hand across his forehead wearily, and drawing his cloak about him like an old man, strode down the street.

Suddenly the idea of the "Redcoats" running before the farmers at Lexington came into his mind's eye. He quickened his steps and threw back his shoulders once again, and as he turned about the corner he ran into some one hastening in the opposite direction. He looked closely at the thick-set, muscular figure.

"Carter Hewes!" he exclaimed.

"Well met, indeed," replied the other, "What think you of the news?"

"Glorious!" said George.

"We will have it all about here soon," said Carter. "You are with us?"

"I am, with all my heart," replied young Frothingham, "to the very end." The two lads shook hands for full a minute.

"Listen! Listen!" said Carter, suddenly. "The bells!—the bells have it, and I would that the King in England could hear them ringing."

"I would better that my brother William were here and listening with us," returned George.

"Ain't it about time for the stage, Cynthy?"

"Why, no, Aunt Patty! Just look at the clock; it's only half past four. The stage doesn't leave the station until five."

"This day's seemed dreadful long, somehow."

"That's because we are expecting Ida," said Cynthia, who was patching a sheet by the light of a west window. "And I suppose the day has seemed long to her, too."

"Yes, poor child, travellin' since ten o'clock this mornin'," said Aunt Patty. "I guess she'll relish our cold chicken 'n' orange marmalade, Cynthy."

"I wonder if she's changed much?" Cynthia put down her work and looked meditatively from the window. "Six years is a long time, Aunt Patty."

"Yes, Ida's a young lady now, dearie," Aunt Patty sighed. "And she's lived so different from what we have, Cynthy. We mustn't expect her to fall into our ways right away. She'll have to learn to love us all over again, you see."

Cynthia turned a tender glance upon the little plainly dressed old woman sitting in the open doorway sewing carpet rags.

"SHE WON'T HAVE ANY TROUBLE LEARNING TO LOVE YOU."

"SHE WON'T HAVE ANY TROUBLE LEARNING TO LOVE YOU."

"She won't have any trouble learning to love you, Aunt Patty," she said. "Just think what we owe to you! Neither of us can ever forget for a moment all you've done for us."

"I haven't done anything but what was my duty, child. When your poor mother died, there wasn't any one but me to take you 'n' Ida; but I've never been able to do for you as I'd like."

"You've done more than one person out of a thousand would have done!" and Cynthia threw down the sheet, crossed the room, and put both arms around the old woman's neck. "Aunt Stina Chase could have taken us. She was rich even then, and could have borne the burden of our support better than you. But she didn't even consider it, and she never did anything for us until she took Ida. And you know it was only because Ida was so pretty that she wanted her. Now that she is going to Europe, she sends Ida back without even consulting you about it."

"Well, dearie, we're glad enough to take her back, I'm[Pg 84] sure. She'll be company for us both these long summer days. And we oughtn't to expect Aunt Stina to take her to Europe. I guess it's pretty expensive livin' in those foreign places."

"I only hope Ida didn't want to go," rejoined Cynthia, returning to her seat by the window. "She'll find it very dull here, anyhow, I'm afraid, after the gay times she's had in the city."

"Yes, poor child," said Aunt Patty, "and we mustn't feel put out if she seems down-hearted just at first. I guess I'd better set about gettin' supper, Cynthy; it's strikin' five."

"Very well; and I'll set the table," said Cynthia, beginning to fold the sheet, "I'm going to put a big vase of flowers in the middle, and I'll give Ida one of the best damask napkins, if you don't mind?"

"Do just as you like, child," said Aunt Patty.

They went into the big pleasant kitchen together. The setting sun filled it with a golden glory; on the braided rug by the stove lay a big Maltese cat, in the south window was a wire stand of plants, and in one corner a tall eight-day clock with a moon on its face. Everything was scrupulously clean and in perfect order. The floor was as white as soap and sand could make it; the pans on the big dresser reflected everything about them, and the stove shone with its coat of polish.

Cynthia sang as she moved about putting the dishes on the table. She was of a happy contented disposition, and never grumbled at anything. She loved her home, plain as it was; she didn't mind hard work, and her simple pleasures satisfied her, though she had often longed for a peep into the great busy world outside Brookville. She had sometimes envied Ida, though she had never allowed Aunt Patty to suspect it, and had wished that she might have shared with her sister the many advantages afforded by city schools and teachers.

Aunt Stina Chase was her father's only sister, and had never known what it was to be poor. She had married a rich man at a very early age, and had been left a widow within a few years. She took her luxurious home, her many servants, her carriage, and her diamonds as a matter of course. But her easy, untroubled life had made her selfish, and when her brother and his wife died within a few months of each other, leaving two little girls to the mercy of the world, she had not thought it incumbent on her to take the children. She had left that to Aunt Patty, who was only a half-sister of the dead mother. But when, years after this, she heard from an acquaintance that Ida, the elder of the two little girls, was exceedingly pretty and attractive, a whim seized her to send for the child.

Aunt Patty had thought it her duty to let Ida go, for Mrs. Chase promised to have the girl instructed in music and the languages, and there was no opportunity at the Brookville school for anything except the plainest sort of an education.

So for six years Ida had made her home in the city, and her occasional letters to Cynthia, who was a year her junior, gave evidence that she was well satisfied with the change of homes.

It was Mrs. Chase who had written that Ida was about to return to Brookville. It was apparently taken for granted that Aunt Patty would welcome her gladly, and there was no hint about reclaiming her when the European trip should be over.

Cynthia thought the letter cold and heartless, and her tender heart ached for her sister. She wondered if Ida had not been cruelly hurt at being so summarily disposed of when her presence was found inconvenient. She wondered, too, how Ida would bear the change from luxury to a very plain way of living, for Cynthia was quite conscious of the limitations of her home, much as she loved it.

"There's the stage, now!" cried Aunt Patty, as the rumble of wheels and the heavy trot of horses' hoofs were heard on the hard road which ran before the house.

They both hurried out to the front gate. The stage had stopped in a cloud of dust, and a tall, slender girl, fashionably attired in a dark blue suit, and hat of rough straw trimmed with blue ribbons, was descending from it.

The driver, assisted by another man, who had volunteered his help, was engaged in taking down a large canvas-covered trunk, on one end of which were the initials "I. S. W."

"IDA, DEAR IDA!" SHE CRIED.

"IDA, DEAR IDA!" SHE CRIED.

Cynthia opened the gate and hastened out into the road. "Ida, dear Ida!" she cried, and threw her arms about her sister. "We are so glad to have you back," the tears rushing to her eyes.

"I suppose you're Cynthia," said Ida, withdrawing herself gently from her sister's embrace. "I never would have known you in the world," her gaze travelling critically over the small figure in the plain dark gown. "Is that the maid at the gate? Ask her to come and take my satchel."

"The maid!" stammered Cynthia, with a startled look. "Oh, Ida! that's Aunt Patty! Here, give me your satchel."

"Pray excuse my mistake," said Ida, in a low voice, as she relinquished the satchel. "Remember, I was not eleven years of age when I left here, and one so soon forgets faces."

Aunt Patty, fortunately, had not heard her niece's questions, and as Ida approached the gate the old woman threw it open, her kindly face beaming.

"You're most welcome, dear child," she said, with a kiss and a little embrace. "But, dear me, how you've changed!"

"That was to be expected, of course," said Ida, as she followed her aunt around the house to the kitchen porch. "I have been away more than six years, you know, Aunt Patty. By-the-way," pausing at the corner of the house, with a glance backward, "do you not use your front door?"

"Not for common," answered Aunt Patty. "I guess you've forgot our Brookville ways. Folks here think it's more sociable to run in 'n' out their kitchens."

"Ah! I had forgotten," said Ida. "We must show them something different."

Cynthia now came close behind them, carrying the satchel. She had stopped to hold open the gate for the two men, who followed her with the trunk.

"We'd better lug it up stairs for ye, Cynthy," said the stage-driver. "It's everlastin' heavy; chockful of gold, I guess," and he laughed, good-naturedly.

"My books make it heavy," said Ida, in a dignified tone.

Cynthia opened the door leading from the kitchen into[Pg 85] the hall, and showed the men up stairs to the neat but barely furnished room her sister was to occupy.

Ida followed, and, after the men had set the trunk down and gone away, she turned to Cynthia with an expression on her young face which was almost severe.

"Surely you don't allow that coarse common stage-driver to call you by your Christian name?" she said.

"Who? Old Jake Storm!" Cynthia looked surprised. "Why, Ida, of course he does! He has known me since I was two years old! He gave me a pair of pigeons once."

"Because he has known you all your life is no reason why he should be lacking in respect for you," rejoined Ida, still severe. "You are no longer a child."

"He doesn't intend it for disrespect, Ida."

"Perhaps not; but he should be made to know his place. Is this to be my room?"

"Yes, Aunt Patty and I thought you would like it better, perhaps, than the one we had together before you went away. We did what we could toward making it comfortable for you, and I do hope you'll like it."

She looked around the spacious chamber as she spoke. To her eyes it looked very attractive, with its bright rag carpet, light pine furniture, and fresh muslin curtains. There was a big crazy-work cushion in the old rocker; a home-made rug of scarlet and black lay before the bureau; and the blue glass vases on the high old-fashioned mantel were full of fragrant June roses. Over the bureau hung a sample of the needle-work for which Aunt Patty had been famous in her youth—a picture in colored silks of a house on a hill-side, a few trees around it, and several thick-waisted children in long pantalettes playing with an oddly shaped black dog.

Ida glanced at the picture as she approached the bureau to lay upon it her hat, which she had just taken off.

"The room is pleasant enough," she said, carelessly. "I can improve it by the addition of a few unframed water-colors I brought with me—my own work, of course. But this wall-paper is hideous," with a little shudder, "and yet it looks fresh."

"Yes, it is new; Aunt Patty chose it," said Cynthia. "The old paper was so ugly. We both thought you wouldn't like it. But this—why, it looks pretty to me, though, of course, I do not pretend to any great artistic taste."

"No, or you would hardly have left that atrocity over my bureau," rejoined Ida. "I believe I used to think it a work of art when I was a child. Now it offends my eye. Take it down, Cynthia; I couldn't sleep with it in the room."

Cynthia bit her lip; but she stepped up on a convenient chair and took down the offending picture.

"There, that is better," said Ida. "And will you have the servant bring me a pitcher of warm water? I must bathe some of this wretched dust from my face."

"I will bring it," said Cynthia; "we don't keep a servant."

"No servant!" Ida stared at her sister. "Why, how in the world do you ever get along without one?"

"We have a woman come to wash every Monday, and the rest of the work we do ourselves."

"By preference?"

"No; we can't afford a servant, Ida. We have to economize very closely."

"I did not imagine your economy extended to doing without a servant. No wonder your hands look so rough, Cynthia. And what an old-fashioned gown you have on! Aunt Patty is your dressmaker, I suppose?"

"Yes," answered Cynthia, flushing with mortification and wounded feeling. "What is wrong with this dress?"

"The sleeves are of a fashion of two years ago, and the skirt doesn't hang well," was the immediate answer. "Well, I know something about dress-making—Aunt Stina used to say I had a natural talent for it—and I will soon put your wardrobe to rights."

"Thank you; I'll give you full liberty with it," said Cynthia. "I'd like to look as much like you as possible, of course, though I'm plain and you are pretty. Now I'll get you the hot water. We have supper at six."

"Supper? Oh, yes, of course; dinner at noon, I presume." A scornful little smile curled Ida's lip. "At Aunt Stina's we had lunch at two and dinner at seven. But, of course, that can't be expected here. You're forgetting that atrocious picture, Cynthia. You might as well take it away now as later."

Cynthia took up the picture and went out, closing the door behind her. She stood for a moment in the hall, staring down at the carpet; then sighed, threw back her head after a little fashion she had when hurt or annoyed, and then, going into her own room, just opposite the one given to Ida, hung the despised picture on an unoccupied nail over her mantel.

"It won't keep me awake," she muttered.

"I think sometimes that I can't stand it another day, Cynthia. It makes me miserable to sit at the table with her, and I have grown to fairly dread meal-times. When she takes her soup she sucks it from the spoon; she drinks her tea with long sips that set my nerves on edge. She drums on the table with her fingers, wipes her mouth on a corner of the table-cloth, and puts her fingers into the bowl of loaf-sugar. I actually saw her once use her thumb to take a fly out of the bowl of honey."

"Anything else?" asked Cynthia, dryly, her brown eyes looking very steadily on her sister's face.

"Yes, dozens of other things. But what is the use of enumerating them? It can't help matters. I only know that I have actually suffered every day of the two weeks I have been here," and Ida sighed heavily as she resumed her[Pg 86] sewing. She was making a dainty little fichu of chiffon and some scraps of old lace. Aunt Patty had found the lace in an old chest of odds and ends of the finery of her early youth, and had at once given it all to Ida.

The two girls were alone in the pleasant sitting-room. Aunt Patty had gone to call upon a sick neighbor, carrying a glass of her golden apple jelly. She was not expected back until supper-time.

"You girls can have a nice, long, pleasant afternoon together," she said on leaving.

But it didn't prove a pleasant afternoon to either Ida or Cynthia, for as usual, when they were out of Aunt Patty's hearing, Ida began to talk of the many things which made her present home unpleasant to her.

"No," said Cynthia, after a long pause, during which she had steadily darned stockings; "talking can't help matters, and you'd better learn as soon as you can to make the best of things, Ida. Aunt Patty is too old now to be made over. It is a pity you could not have gone to Europe with Aunt Stina."

"It was more than a pity, it was a shame," said Ida, flushing. "But while I hoped she'd offer to take me, I did not expect it. Aunt Stina is refined to the last degree, and has elegant manners, but she is not generous. During the six years I was with her she kept scrupulously to her bargain; she gave me a home, and paid my school bills—nothing more."

"Never any presents?" asked Cynthia.

"Nothing, except finery and old clothes for which she had no further use herself. It was pretty hard sometimes; there were so many things I wanted. But I never hinted nor asked for any thing. In the first place, I was too proud, and then I knew it would be useless. She never cared to spend her money on any one except herself, and often complained bitterly at having to pay such heavy school bills."

"It must have made you feel dreadfully," said Cynthia. "Now Aunt Patty hasn't a stingy bone in her body."

"No; she's very generous," admitted Ida.

"You'd say that more heartily if you knew how she used to pinch and contrive in order to send you a little extra money, Ida. She was always making little plans for you, and was so proud whenever you wrote that you'd taken a prize."

"She has her good qualities, of course, Cynthia; I admit that. But I do wish she understood a little about table etiquette. I don't wonder now that Aunt Stina used to shrug her shoulders and smile whenever Aunt Patty's name was mentioned. She often used to say that I didn't realize from what a depth she had rescued me."

A little spark of indignation burned in Cynthia's brown eyes as she looked up quietly.

"It was unkind of her to say that," she exclaimed. "And why was she willing to send you back to such an uncivilized place?"

"Because she found it convenient to do so," answered Ida, coolly. "Self first, always, with Aunt Stina."

"And it is never self with Aunt Patty." Cynthia's tone was warm. "What do her little peculiarities matter? If you made up your mind not to let them annoy you, Ida, you would soon cease to notice them."

Ida shook her head and smiled incredulously. "They would always annoy me," she said. "I pity you, Cynthia, for having had to live with her all these years."

"You needn't; I have never pitied myself."

"Well, you are used to her, and of course that makes a great difference. You probably don't notice things that drive me nearly wild."

"There you are mistaken, Ida. But when I think how Aunt Patty took us in when we were troublesome little children, homeless and penniless, and how many sacrifices she has made for us, I feel that I can't do enough to show my love and gratitude. And I believe the day will come when you will appreciate her just as I do, and be heartily sorry that you ever allowed yourself to be ashamed of her, or to utter one word to her discredit."

"Well, I declare, Cynthia, you have read me quite a lecture." Ida laughed as she spoke. She did not seem at all offended. "You are a quaint, old-fashioned little soul, Cynthia. I suppose you don't realize it, though. I wonder if I would have been like you if Aunt Stina had left me here?"

Tears stood thickly in Cynthia's eyes. She wiped them away with the stocking she was darning. She could not trust herself to say another word.

"Have I offended you by calling you quaint and old-fashioned?" asked Ida. "Well, then, you must forgive me, Cynthia, for I didn't intend to be unkind."

Cynthia, who loved her sister dearly in spite of her faults, could not resist the kiss Ida laid lightly on her cheek. She smiled through her tears. "I must try not to be so sensitive," she said. "Of course I know I must strike you as peculiar; I'm so different from the other girls you have known. That Angela Leverton, for instance, to whom you are always writing."

"Oh, Angela is not perfection by any means," said Ida. "But she is very refined, and nothing she does is ever out of taste. We were inseparable, and I miss her dreadfully now."

"Why not have her come to spend a few weeks with us this summer?" asked Cynthia. "I know Aunt Patty—" She stopped suddenly, then added, in a changed tone: "But, of course, it wouldn't do; you'd be ashamed to have her see how you're living now."

"No, I wouldn't care to have her come," said Ida, frankly. "She wouldn't enjoy a visit of even a few days. What could I do to amuse her? Take her to the store to get weighed, I suppose, and to the meetings of your little Band of Hope Circle."

Cynthia laughed. "It isn't very gay here, that's a fact," she said.

Ida had finished the fichu, and was now trying its effect upon herself before the little mirror between the two windows. Suddenly she gave a little start. "There's Mrs. Lennox's carriage coming down the road," she said. "Cynthia, I do believe it is going to stop here. Yes, it has stopped, and Mrs. Lennox is getting out. Where shall we receive her? That dreadfully stuffy parlor—"

"Go out and meet her on the front porch," said Cynthia. "She can sit down there. It is you she wants to see, of course. If she asks for me, you can let me know."

Ida was so graceful in her air of taking it as a matter of course that Mrs. Lennox would prefer a seat on the vine-clad porch, that it did not occur to that lady to wonder why she was not asked into the parlor.

Mrs. Lennox, moreover, was no stickler for ceremony. She was a gentle, refined woman, whose heart was overflowing with good-will toward every one. She found her greatest happiness in making others happy, and it was with the object of contributing a little toward the pleasure of Mrs. Patty Dean's two nieces that she had come to call upon them.

She lived in a handsome house, a mile from the village, and entertained a great deal during the summer, spending the winter months in the South.

"I have noticed you at church," she said to Ida, "and I have been intending every day to call upon you, but I have had a houseful of company. You have been here about a fortnight, I think, and of course you have had a very happy time with your dear aunt and sister; but I hope you will not object to a little dissipation now, for I want you and Cynthia to come to a lawn party I expect to give next Tuesday."

"How delightful! And how kind of you to think of us!" said Ida.

"Ah! but I need all the young girls I can muster, and I expect several from town," rejoined Mrs. Lennox. "One of them, Angela Leverton, writes me that she is a particular friend of yours."

"Angela! coming to Brookville!" exclaimed Ida. There was consternation as well as surprise in her voice.

"Yes; she will make me a visit of a week or ten days. I expect her on Saturday. Now can I depend on having you and Cynthia for my lawn party?"

"Yes, I—I think so," answered Ida, whose heart was beating very fast. "It is so good of you to want us, Mrs. Lennox."

When, a few minutes later, Mrs. Lennox went away, Ida accompanied her to the gate, and stood there after the carriage had disappeared from view. She stared straight before her, a little frown on her smooth white brow. She was trying to make up her mind to do something which her conscience, that infallible monitor, told her was both mean and unkind. She started and colored when Cynthia's voice fell suddenly on her ear.

"I thought you were never coming in, Ida," she said. "What did Mrs. Lennox want?"

"She wanted to invite me to a garden party," answered Ida, without looking at her sister. "But of course I can't go. I have nothing fit to wear."

"Not go!" exclaimed Cynthia. "Oh, Ida, you must! It will be perfectly delightful. She gave one last year, and had a band of music, fireworks, refreshments served in tents, colored lanterns on the trees, and everything else you can imagine. She told me all about it herself, when she called one day soon after to see Aunt Patty, and she promised that if she ever gave another I should be invited. I suppose, however, she forgot it, or perhaps she thinks I'm too young. Anyhow, I'm glad she asked you."

"Yes; it was very nice of her," rejoined Ida, in a stiff tone. "But I really have nothing suitable for such an occasion, and I am sure you have no party dress, Cynthia."

"No; but if she had invited me I could have worn my pink organdie."

"That faded, forlorn thing!"

"Well, what would it matter? No one would pay any attention to me at such a place. I would enjoy myself just looking on. But I wasn't invited, so there is no use talking about it," and she turned around and walked back to the house, a look of disappointment on her face.

Ida leaned over the gate again.

"I suppose I've done a mean thing," she thought. "But it is too late now to alter matters. Moral courage isn't my specialty, I imagine," and she sighed heavily.

Just then a quaint figure, waving an old green silk parasol, came into sight around a bend in the road. It was Aunt Patty. Her face fairly beamed as she saw Ida.

"Watching for me, dearie?" she called out, as she drew within speaking-distance. "Bless your tender heart! Well, I've something grand to tell you girls. Such good news. Where's Cynthia?"

The Imp opened a small door upon the right of the room, and through it Jimmieboy saw another apartment, the walls of which were lined with books, and as he entered he saw that to each book was attached a small wire, and that at the end of the library was a square piece of snow-white canvas stretched across a small wooden frame.

"Magic lantern?" he queried, as his eye rested upon the canvas.

"Kind of that way," said the Imp, "though, not exactly. You see, these books about here are worked by electricity, like everything else here. You never have to take the books off the shelf. All you have to do is to fasten the wire connected with the book you want to read with the battery, turn on the current, and the book reads itself to you aloud. Then if there are pictures in it, as you come to them they are thrown by means of an electric light upon that canvas."

"Well, if this isn't the most—" began Jimmieboy, but he was soon stopped, for some book or other off in the corner had begun to read itself aloud.

"And it happened," said the book, "that upon that very night the Princess Tollywillikens passed through the wood alone, and on approaching the enchanted tree threw herself down upon the soft grass beside it and wept."

Here the book ceased speaking.

"That's the story of Pixyweevil and Princess Tollywillikens," said the Imp. "You remember it, don't you?—how the wicked fairy ran away with Pixyweevil, when he and the Princess were playing in the King's gardens, and how she had mourned for him many years, never knowing what had become of him? How the fairy had taken Pixyweevil and turned him into an oak sapling, which grew as the years passed by to be the most beautiful tree in the forest?"

"Oh yes," said Jimmieboy. "I know. And there was a good fairy who couldn't tell Princess Tollywillikens where the tree was, or anything at all about Pixyweevil, but did remark to the brook that if the Princess should ever water the roots of that tree with her tears, the spell would be broken, and Pixyweevil restored to her—handsomer than ever, and as brave as a lion."

"That's it," said the Imp. "You've got it; and how the brook said to the Princess, 'Follow me, and we'll find Pixyweevil,' and how she followed and followed until she was tired to death, and—"

"Full of despair threw herself down at the foot of that very oak and cried like a baby," continued Jimmieboy, ecstatically, for this was one of his favorite stories.

"Yes, that's all there; and then you remember how it winds up? How the tree shuddered as her tears fell to the ground, and how she thought it was the breeze blowing through the branches that made it shudder?" said the Imp.

"And how the brook laughed at her thinking such a thing!" put in Jimmieboy.

"And how she cried some more, until finally every root of the tree was wet with her tears, and how the tree then gave a fearful shake, and—"

"Turned into Pixyweevil!" roared Jimmieboy. "Yes, I remember that; but I never really understood whether Pixyweevil ever became King? My book says, 'And so they were married, and were happy ever afterwards'; but doesn't say that he finally became a great potteringtate, and ruled over the people forever."

"I guess you mean potentate, don't you?" said the Imp, with a laugh—potteringtate seemed such a funny word.

"I guess so," said Jimmieboy. "Did he ever become one of those?"

"No, he didn't," said the Imp. "He couldn't, and live happy ever afterwards, for Kings don't get much happiness in this world, you know."

"Why, I thought they did," returned Jimmieboy, surprised to hear what the Imp had said. "My idea of a King was that he was a man who could eat between meals, and go to the circus whenever he wanted to, and always had plenty of money to spend, and a beautiful Queen."

"Oh no," returned the Imp. "It isn't so at all. Kings really have a very hard time. They have to be dressed up all the time in their best clothes, and never get a chance, as you do, for instance, to play in the snow or in summer in the sand at the seashore. They can eat between meals if they want to, but they can't have the nice things you have. It would never do for a King to like ginger-snaps and cookies, because the people would murmur and say, 'Here—he is not of royal birth, for even we, the common people, eat ginger-snaps and cookies between meals; were he the true King he would call for green peas in winter-time, and boned turkey, and other rich stuffs that cost much money, and are hard to get; he is an impostor; come, let us overthrow him.' That's the hard part of it, you see. He has to eat things that make him ill just to keep the people thinking he is royal and not like them."

"Then what did Pixyweevil become?" asked Jimmieboy.

"A poet," said the Imp. "He became the poet of every-day things, and of course that made him a great poet. He'd write about plain and ordinary good-natured puppy-dogs, and snow-shovels, and other things like that, instead of trying to get the whole moon into a four-line poem, or to describe some mysterious thing that he didn't know much about in a ten-page poem that made it more mysterious than ever, and showed how little he really did know about it."

"I wish I could have heard some of Pixyweevil's poems," said Jimmieboy. "I liked him, and sometimes I like poems."

"Well, sit down there before the fire, and I'll see if we can't find a button to press that will enable you to hear them. They're most of 'em nonsense poems, but as they are perfect nonsense they're good nonsense."

"It is some time since I've used the library," said the Imp, gazing about him as if in search of some particular object. "For that reason I have forgotten where everything is. However, we can hunt for what we want until we find it. Perhaps this is it," he added, grasping a wire and fastening it to the battery. "I'll turn on the current and let her go."

"NO WONDER IT WOULDN'T SAY ANYTHING," HE CRIED.

"NO WONDER IT WOULDN'T SAY ANYTHING," HE CRIED.

The crank was turned, and the two little fellows listened very intently, but there came no sound whatever.

"That's very strange," said the Imp, "I don't hear a thing."

"Neither do I," observed Jimmieboy, in a tone of disappointment. "Perhaps the library is out of order, or the battery may be."

"I'll have to take the wire and follow it along until I come to the book it is attached to," said the Imp, stopping the current and loosening the wire. "If the library is out of order it's going to be a very serious matter getting it all right again, because we have all the books in the world here, and that's a good many, you know—more'n a hundred by several millions. Ah! Here is the book this wire worked. Now let's see what was the matter."

In a moment the whole room rang with the Imp's laughter.

"No wonder it wouldn't say anything," he cried. "What do you suppose the book was?"

"I don't know," said Jimmieboy. "What?"

"An old copy-book with nothing in it. That's pretty good!"

At this moment the telephone bell rang, and he had to go see what was wanted.

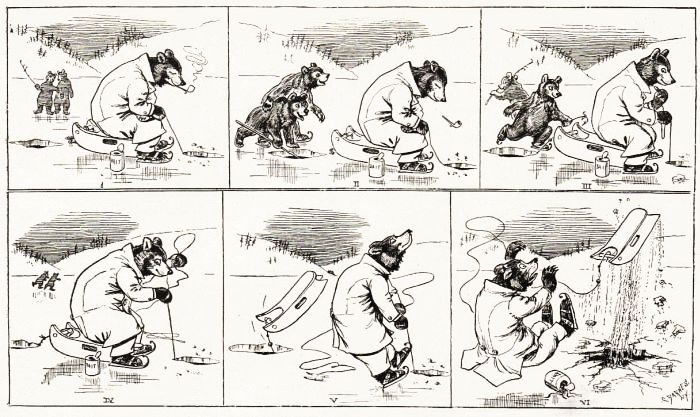

"Excuse me for a moment, Jimmieboy," the Imp said, as he started to leave the room. "I've got to send a message for somebody. I'll turn on one of the picture-books, so that while I am gone you will have something to look at."

The Imp then fastened a wire to the battery, turned on the current, and directing Jimmieboy's attention to the sheet of white canvas at the end of the library, left the room.

Never before was the chafing-dish so popular as now. And yet, in spite of the books that have been written directing how it is to be used, and the classes that have been formed for learning its capabilities, there is still a very general impression that its chief function is to cook Welsh-rarebit. As there is a prejudice against these as unwholesome, it is not strange, perhaps, that young girls and lads have had little practice with the chafing-dish. It has been rather reserved for their seniors, whose digestions may be supposed to have become case-hardened. But there are many other delicious dishes besides Welsh-rarebit which may be cooked over an alcohol flame. Even this much-abused compound, if properly prepared, and eaten at a reasonable hour, need not cause dyspepsia. It has gained a bad name because it is usually devoured late at night, and not followed by the vigorous exercise that is necessary if one would digest cheese comfortably.

The chafing-dish, however, is a really valuable aid in teaching young people something about cookery, and that in an easy, pleasant fashion. A chafing-dish is a charming possession for a young girls' club in which light and inexpensive refreshments are served. It is not always easy for the cook to prepare eatables for a club that meets every week or fortnight; and yet all girls—and boys—know how the sociability of any little gathering of this sort is heightened if there is something to eat. Girls who cannot have the "spread" prepared in the kitchen generally regale themselves with cream-puffs or éclairs, chocolate creams or caramels. And the boys—what do the boys eat? Peanuts, apples, pop-corn balls, varied by chewing-gum, and occasionally a cigarette "on the sly." Surely none of these are as good or as wholesome as some hot dainty prepared in a chafing-dish. The constant nibbling at sweets is very likely to prove injurious in the long-run, and to cost as much as the chafing-dish cookery.

But, some one may ask, what is there that can be cooked in a chafing-dish that will not give trouble to prepare in advance? There is no sense in planning for dishes that will keep the cook at work for an hour or so beforehand.

Certainly not. The right sort of chafing-dish cookery can all be done, at a pinch, in a chafing-dish. This ceases to be useful when it makes demands upon the kitchen stove, the cook, and every-day pots and pans.

There are many delicacies that the little cook can prepare with no help except that of her own clear head and her deft hands. It is not worth while to rehearse all of the dainties she has at her command, but here are a few of them: Scrambled eggs, eggs with cheese, eggs with curry, poached eggs, eggs with tomatoes, eggs with ham, curried eggs, creamed salmon, grilled sardines, panned oysters, broiled oysters, stewed and creamed oysters or clams, barbecued[Pg 89] ham, fricasseed dried beef, creamed tomatoes, and cheese fondu.

For none of these need the cook's services be required, nor call be made upon the larder for any but uncooked provisions, except in the dishes where ham is used. And in these days, when cold boiled ham may be bought at every delicatessen shop and many groceries, it is no more trouble to supply one's self with that than with fresh eggs.

The girl who wishes to provide a feast for the little club or circle to which she belongs, should first make out a list of all the utensils and materials she will need. Then she may collect them and arrange them upon the table where she means to do her cookery. The chafing-dish must stand on a tray; close at hand should be a half-pint measuring-cup, a small wooden spoon for stirring, a couple of teaspoons, a table-spoon, and a knife. If eggs are to be cooked there must be a small bowl to beat them in and a fork. The ingredients must be arranged in the order in which the cook will have to use them.