CAMBRIDGE BIOLOGICAL SERIES.

General Editor:—Arthur E. Shipley, M.A., F.R.S.

FELLOW AND TUTOR OF CHRIST’s COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE.

GRASSES.

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE,

C. F. CLAY, Manager.

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

Edinburgh: 100, PRINCES STREET.

ALSO

London: H. K. LEWIS, 136, GOWER STREET, W.C.

Leipzig: F. A. BROCKHAUS.

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS.

Bombay and Calcutta: MACMILLAN & CO. Ltd.

[All Rights reserved.]

A HANDBOOK FOR USE IN THE FIELD

AND LABORATORY.

BY

H. MARSHALL WARD, Sc.D., F.R.S.

LATE PROFESSOR OF BOTANY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE.

CAMBRIDGE:

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS.

1908

First Edition 1901

Reprinted 1908

THE following pages have been written in the hope that they may be used in the field and in the laboratory with specimens of our ordinary grasses in the hand. Most of the exercises involved demand exact study by means of a good hand-lens, a mode of investigation far too much neglected in modern teaching. The book is not intended to be a complete manual of grasses, but to be an account of our common native species, so arranged that the student may learn how to closely observe and deal with the distinctive characters of these remarkable plants when such problems as the botanical analysis of a meadow or pasture, of hay, of weeds, or of “seed” grasses are presented, as well as when investigating questions of more abstract scientific nature.

I have not hesitated, however, to introduce general statements on the biology and physiological peculiarities of grasses where such may serve the purpose of interesting the reader in the wider botanical bearings of the subject, though several reasons may be urged against extending this part of the theme in a book intended to be portable, and of direct practical use to students in the field.

I have pleasure in expressing my thanks to Mr R. H. Biffen for carefully testing the classification of “seeds" on pp. 135-174, and to him and to Mr Shipley for kindly looking over the proofs; also to Mr Lewton-Brain, who has tested the classification of leaf-sections put forward on pp. 72-82, and prepared the drawings for Figs. 21-28.

That errors are entirely absent from such a work as this is perhaps too much to expect: I hope they are few, and that readers will oblige me with any correctionsvi they may find necessary or advantageous for the better working of the tables.

The list of the chief authorities referred to, which students who desire to proceed further with the study of grasses should consult, is given at the end.

I have pleasure in acknowledging my indebtedness to the following works for illustrations which are inserted by permission of the several publishers:—Stebler’s Forage Plants (published by Nutt & Co.), Nobbe’s Handbuch der Samenkunde (Wiegandt, Hempel and Parey, Berlin), Harz’s Landwirthschaftliche Samenkunde (Paul Parey, Berlin), Strasburger and Noll’s Text-Book of Botany (Macmillan & Co.), Figuier’s Vegetable World (Cassell & Co.), Lubbock’s Flowers, Fruits and Seeds (Macmillan & Co.), Kerner’s Natural History of Plants (Blackie & Son), and Oliver’s First Book of Indian Botany (Macmillan & Co.).

It is impossible to avoid the question of variation in work of this kind, and students will without doubt come across instances—especially in such genera as Agropyrum, Festuca, Agrostis and Bromus—of small variations which show how impossible it is to fit the facts of living organisms into the rigid frames of classification. It may possibly be urged that this invalidates all attempts at such classifications: the same argument applies to all our systems, though it is perhaps less disastrous to the best Natural Systems which attempt to take in large groups of facts, than to artificial systems selected for special purposes. Perhaps something useful may be learned by showing more clearly where and how grasses vary, and I hope that the application to them of these preliminary tests may elucidate more facts as we proceed.

H. M. W.

Cambridge, April, 1901.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Vegetative Organs | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Vegetative Organs (continued) | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

Grasses Classified according to their Vegetative Characters | 39 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Anatomy and Histology | 62 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

Grasses Classified according to the Anatomical Characters of the Leaf | 72 |

| viiiCHAPTER VI. | |

| Grasses in Flower | 83 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

Grasses Grouped according to their Flowers and Inflorescences | 99 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Fruit and Seed | 119 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Classification of Grasses by the “Seeds" (Grains) | 135 |

| Bibliography | 175 |

| Index, Glossary and List of Synonyms | 177 |

That grasses are interesting and important plants is a fact recognised by botanists all the world over, yet it would appear that people in general can hardly have appreciated either their interest or their importance seeing how few popular works have been published concerning their structure and properties.

Apart from their almost universal distribution, and quite apart from the fascinating interest attaching to those extraordinary tropical giants, the Bamboos, West Indian Sugar-cane, the huge Reed-grasses of Africa, the Pampas-grasses of South America; and from the utilitarian value of the cereals—Maize, Rice, Wheat and other corn, &c.—everyone must be struck by the significance of the enormous tracts of land covered by grasses in all parts of the world, the Prairies of North America and the Savannahs of the South, the Steppes of Russia and Siberia, and the extensive tracts of meadow and pasture-land in Europe being but a few examples.

Although in the actual number of species the Grass family is by no means the largest in the vegetable kingdom, for there are far more Composites or Orchids, the curious sign of success in the struggle for existence comes out in grasses in that the number of individuals far transcends those of any other group, and that they have taken possession of all parts of the earth’s surface. Some species are cosmopolitan—e.g. our common Reed, Arundo Phragmites; while others—e.g. several of our native species of Festuca and Poa—are equally common in both hemispheres. On the whole the Tropics afford most species and fewest individuals, and the temperate regions most individuals.

Considering their multifarious uses as fodder and food, for brewing, weaving, building and a thousand other purposes, it is perhaps not too much to say that if every other species of plant were displaced by grasses of all kinds—as many indeed gradually are—man would still be able to supply his chief needs from them.

The profound significance of the grass-carpet of the earth, however, comes out most clearly when we realise the enormous amounts of energy daily stored up in the countless myriads of green blades as they fix their carbon. By decomposing the carbon-dioxide of the air in their chlorophyll apparatus by the action of the radiant energy of the sun, they build up starches and sugars and other plant-substances, which are then consumed and turned into flesh by our cattle and sheep and other herbivorous animals, and so furnish us with food. The whole theory of agriculture turns on this pivot, and the by no means3 small modicum of truth in such sayings as “All flesh is grass,” and that the man who can make two blades of grass grow where one grew before deserves well of his country, obtains a larger significance when it is realised that the only real gain of wealth is that represented by the storage of energy from without which comes to us by the action of green leaves waving in the sunshine.

The true Grasses, comprising the Natural Order Graminaceæ—also written Gramineæ—are often popularly confounded with other herbs which possess narrow green ribbon-like leaves, or even with plants of very different aspects—e.g. Cotton-grass (Eriophorum) and other Sedges, and the names Rib-grass (Plantago), Knot-grass (Polygonum), Scorpion-grass (Myosotis) and Sea-grass (Zostera), as well as the general usage of the word grass to signify all kinds of leguminous and other hay-plants in agriculture, point to the wider use of the word in former times. This has been explained by the use of the words gaers, gres, gyrs, and grass in the old herbals to indicate any kind of small herbage.

In view of the importance of our British grasses in agriculture, I have here put together some results of observation and reading in the hope that they may aid students in recognising easily our ordinary agricultural and wild grasses. During several years of work in the fields, principally directed at first to the study of the parasitic fungi on grasses, and subsequently to that of the importance of grasses in forestry and agriculture, and to the variations they exhibit, the need of some guide to the identification of a grass at any time of the year,4 whether in flower or not, forced itself on the attention, and although a botanist naturally turns to a good Flora when he has the grass in flower, as the best and quickest way of ascertaining the species, it soon became evident that much may be done by the study of the leaves and vegetative parts of most grasses. Indeed some are recognisable at a glance by certain characters well known to continental observers: in the case of others the matter is more difficult, and perhaps with a few it is impossible to be certain of the species from such characters only.

Nevertheless, while the best means for the determination of species are always in the floral characters so well worked up in the Floras of Hooker, Bentham and others, there is unquestionably much value in the characters of the vegetative organs also, as the works of Jessen, Lund, Stebler, Vesque and others abroad, and Sinclair, Parnell, Sowerby and others in this country attest.

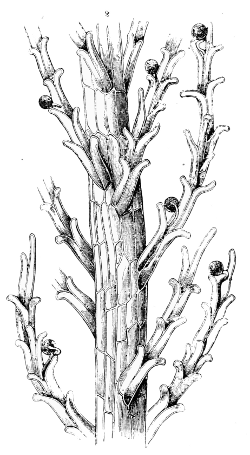

Almost the only plants confounded with true grasses by the ordinary observer are the sedges and a few rushes. Apart from the very different floral structures, there are two or three easily discoverable marks for distinguishing all our grasses from other plants (Fig. 1). The first is their leaves are arranged in two rows, alternately, up the stems; and the second that their stems are circular or flattened in section, or if of some other shape they are never triangular and solid1 (Figs. 6 and 7). Moreover the leaves are always of some elongated shape, and without 5leaf-stalks2, but pass below into a sheath, which runs some way down the stem and is nearly always perceptibly split 6(Figs. 8-13). Further, the stems themselves are usually terete, and distinctly hollow except at the swollen nodes, and only branch low down at the surface of the ground or below it3.

Fig. 1. A plant of Oat (Avena), an example of a typical grass, showing tufted habit and loose paniculate inflorescence (reduced). Figuier.

All our native grasses are herbaceous, and none of

them attain very large dimensions. In the following lists

I term those small which average about 6-18 inches in

the height of the tufts, whereas those over 3 feet high

may be termed large, the tufts being regarded as in

flower. The sizes cannot be given very accurately, and

starved specimens are frequently found dwarfed, but in

most cases these averages are not far wrong for the

species freely growing as ordinarily met with, and in

some cases are useful. I have omitted the rare species

throughout, and in the annexed lists have added the

popular names.

Large Grasses.

(Over 3 feet.)

Milium effusum (Millet-grass).

Digraphis arundinacea (Reed-grass).

Aira cæspitosa (Tufted Hair-grass).

Arrhenatherum avenaceum (False Oat).

Elymus arenarius (Lyme-grass).

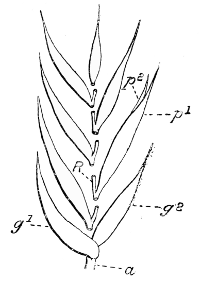

Bromus asper (Hairy Brome).

B. giganteus (Tall Brome).

Festuca elatior (Meadow Fescue).

F. sylvatica (Reed Fescue).

Glyceria aquatica (Reed Sweet-grass).

G. fluitans (Floating Sweet-grass).

Arundo Phragmites (Common Reed).

Medium Grasses.

(1-3 feet.)

Phleum pratense (Timothy).

Avena pratensis (Perennial Oat-grass).

Anthoxanthum odoratum (Sweet Vernal).

Alopecurus agrestis (Slender Foxtail).

A. pratensis (Meadow Foxtail).

Agrostis alba (Fiorin).

Psamma arenaria (Sea Mat-grass).

Avena flavescens (Yellow Oat-grass).

Holcus lanatus (Yorkshire Fog).

Hordeum sylvaticum (Wood Barley).

H. pratense (Meadow Barley).

Agropyrum repens (Couch-grass).

A. caninum (Fibrous Twitch).

Lolium italicum (Italian Rye-grass).

Brachypodium sylvaticum (Wood False-Brome).

B. pinnatum (Heath False-Brome).

Bromus erectus (Upright Brome).

B. sterilis (Barren Brome).

B. arvensis (Field Brome).

Festuca ovina (var. rubra, &c.). (Sheep’s Fescue).

F. elatior (var. pratensis). Meadow Fescue.

Dactylis glomerata (Cock’s-foot).

Cynosurus cristatus (Crested Dog’s-tail).

Poa pratensis (Meadow-grass).

P. trivialis (Rough stalked Meadow-grass).

P. nemoralis (Wood Poa).

Molinia cærulea (Flying Bent).

Melica nutans (Mountain Melick).

M. uniflora (Wood Melick).

Small Grasses.

(6-18 inches.)

Phleum arenarium (Sand Cat’s-tail).

Alopecurus geniculatus (Marsh Foxtail).

Agrostis canina (Brown Bent).

Aira flexuosa (Wavy Hair-grass).

8 Aira canescens (Grey Hair-grass).

A. præcox (Early Hair-grass).

A. caryophyllea (Silvery Hair-grass).

Nardus stricta (Moor Mat-grass).

Hordeum murinum (Wall Barley).

H. maritimum (Sea Barley).

Lolium perenne (Rye-grass).

L. temulentum (Darnel).

Brœmus arvensis (var. mollis). (Field Brome).

Festuca ovina (Sheep’s Fescue).

F. Myuros (Rat’s-tail Fescue).

Briza media (Quaking-grass).

Poa maritima (Sea Poa).

P. annua (Annual Meadow-grass).

P. compressa (Flattened Meadow-grass).

P. alpina (Alpine Poa).

P. bulbosa (Bulbous Poa).

Triodia decumbens (Heath-grass).

Kœleria cristata (Crested Kœleria).

The roots of our grasses are almost always thin and

fibrous and are adventitious from the nodes, frequently

forming radiating crowns round the base and easily pulled

up, and usually broken in the process; but in the case

of a few moor grasses—especially Nardus (Fig. 2) and

Molinia—the roots are so tough and thick (stringy) as to

resist breakage very efficiently. In stoloniferous grasses a

similar difficulty of removal may be caused in a slighter

degree by the underground stems. In a few cases, e.g.

Alopecurus bulbosus (Fig. 3), Poa bulbosa, Phleum pratense

and P. Bœhmeri, Arrhenatherum avenaceum, and to a

slighter extent in Poa alpina and one or two others, the

lowermost internodes and sheaths of the stems may be

swollen and stored with food-materials, and a sort of tuber

or bulb results; this is especially apt to occur in dry sandy

9

10soils. In old lawns, pastures, &c., the roots of Poa annua

and others may have nodules on them due to the presence

of certain small Nematode worms, Heterodera.

Fig. 2. Nardus stricta. Plant showing tufted habit, and simple spikate inflorescence, with pointed spikelets all turned towards one side (secund) on the rachis (reduced). Note also the bristle-like (setaceous) leaves at length reflexed. Parnell. |

Fig. 3. Alopecurus geniculatus, var. bulbosus. Plant (reduced) showing habit, bulbous shoots and cylindrical spike-like inflorescences (Foxtail type). Notice the inflated sheaths, and the “kneed" lower parts of the ascending stems. Parnell. |

Grasses are annual, biennial, or perennial, and it is

often of importance to know which. The point may usually

be determined by examining the shoots. If all the shoots

have flowering stems in them, and are evidently of the

current year, the grass is an annual; but if any shoots

have leaves only, it is either biennial or perennial: to

determine which is not always easy, but in perennial

grasses there will generally be evident remains of older

leaf-bases and shoots, and if there are distinct underground

stolons or creeping rhizomes as well the point

may be considered decided, and the grass is perennial, as

is the case with most of our important species. If all the

shoots are barren, the grass is a biennial in its first year

of growth: if all have flowering stems in them, but show

traces of old leaf-bases of the previous year, then the grass

is a biennial in its second year. The proof of biennial

character is not always easy, however, and a few grasses

may be either annual or biennial, or biennial or perennial,

according to conditions—e.g. species of Hordeum, Bromus,

&c. In the following lists I have given the duration of

the principal grasses, where the character is especially

important.

Annuals.

Phleum arenarium.

Aira præcox.

A. caryophyllea.

Hordeum murinum.

H. maritimum.Lolium temulentum.

Festuca Myurus.

Briza minor.

Poa rigida.

P. annua.Annuals

which may become biennial or perennial.

Alopecurus geniculatus.

Hordeum pratense.

Lolium perenne.

L. italicum (may be perennial).

Bromus asper (may be perennial).

B. sterilis.

B. arvensis (may be perennial).Perennials.

Holcus lanatus.

H. mollis.

Nardus.

Hordeum sylvaticum.

Agropyrum.

Brachypodium.

Bromus erectus.

B. giganteus.

Festuca ovina.

F. elatior.

F. sylvatica.

Dactylis.

Cynosurus cristatus.

Briza media.

Milium.

Anthoxanthum.

Digraphis.

Phleum pratense.

Alopecurus pratensis.

Agrostis alba.

A. canina.Psamma.

Aira cæspitosa.

A. flexuosa.

A. canescens.

Avena pratensis.

A. flavescens.

Arrhenatherum.

Glyceria aquatica.

G. fluitans.

Poa maritima.

P. compressa.

P. pratensis.

P. trivialis.

P. nemoralis.

P. alpina.

P. bulbosa.

Molinia.

Melica.

Triodia.

Kœleria.

Arundo.

Fig. 4. Catabrosa aquatica. Plant showing the creeping habit, rooting nodes, and paniculate inflorescence (reduced). Parnell.

The rhizome of a perennial grass is continued sympodially

by means of buds branching from the lowermost

joints of the flowering shoots, and some importance is

attached to the mode of spreading of these lateral sprout12ing

shoots. The buds always arise in the axils of the lower

leaf-sheaths—i.e. they are intra-vaginal. If they remain

intra-vaginal during further growth, the shoots are forced

upwards and only tufts (Fig. 2) are formed, except in so far

as such shoots may fall prostrate on the surface of the

ground later, and throw out roots from their nodes, and

so act as runners or offsets, or put out a few roots &c.

as they ascend through the soil. But in many cases the

buds soon burst through the leaf-sheaths, and develope

as extra-vaginal shoots, and may then run horizontally

as underground stolons. Only creeping grasses of these

latter kinds can rapidly cover large areas4: the grasses

13

with intra-vaginal shoots only can only make tufts or

"tussocks." Several peculiarities in the habits of grasses

depend on these facts. The following are the most

important creeping, or stoloniferous species, contrasted

with the much more common tufted and the far rarer

grasses with runners above ground (Fig. 4). Some of

these (Elymus, Psamma, &c.) are of great importance as

sand-binders.

With intra-vaginal branches only.

Lolium—slightly stoloniferous.

Festuca elatior—slightly stoloniferous.

Avena flavescens—slightly stoloniferous.

Phleum pratense—no stolons, but may be bulbous.

Dactylis—no stolons.

Festuca ovina—no stolons.

Poa alpina—no stolons.

Cynosurus—no stolons.With extra-vaginal shoots.

Arrhenatherum—short stolons, sometimes bulbous.

Holcus lanatus—creeping.

Alopecurus pratensis—long stolons.

Anthoxanthum—slightly stoloniferous.

Agrostis alba (var. stolonifera)—long stolons and runners.

Digraphis—long stolons.

Poa pratensis—long stolons.

P. trivialis—runners only.

Festuca heterophylla, Lam.—a variety of F. ovina with slight stolons.

F. rubra (Linn.)—a variety of F. ovina with long stolons.

Bromus erectus—no stolons.

B. inermis—long stolons.Creeping below ground and truly stoloniferous.

Agropyrum.

Elymus.

Psamma.

Poa pratensis.

P. compressa.

Agrostis alba (var. stolonifera).

Alopecurus pratensis.

Brachypodium (slightly).Bromus erectus (slightly).

Festuca ovina (var. rubra, Linn.).

F. elatior (slightly).

Briza (slightly).

Glyceria.

Poa maritima.

Melica.

Arundo.Tufted Grasses.

Milium.

Agrostis alba (on downs, &c.).

Aira cæspitosa.

A. flexuosa.

A. canescens.

A. præcox.

A. caryophyllea.

Avena pratensis (slightly creeping).

Arrhenatherum.

Nardus (Fig. 2).

Hordeum sylvaticum.

Lolium.

Bromus.

Festuca ovina (except some varieties).F. sylvatica.

F. Myurus.

Dactylis.

Cynosurus.

Poa rigida.

P. annua.

P. trivialis.

P. nemoralis.

P. alpina.

P. bulbosa.

Molinia.

Triodia.

Kœleria.Creeping above ground (with runners).

Holcus lanatus.

Alopecurus geniculatus.

Agrostis alba (var. stolonifera).

Hordeum pratense (slightly).

H. murinum (slightly).

Catabrosa (Fig. 4).

Cynodon (Fig. 5).

Hackel has pointed out that a distinction must be drawn

between the true nodes of the culm, and the swellings15

Fig. 5. Cynodon Dactylon. Plant (reduced) showing creeping and stoloniferous habit, and peculiar inflorescence of digitate

spikes. Parnell.often found at the base of the sheaths themselves over

these: the latter are often conspicuous when the

former are inconspicuous—e.g.

most species of Agrostis, Avena,

Festuca, &c.

Fig. 5. Cynodon Dactylon. Plant (reduced) showing creeping and stoloniferous habit, and peculiar inflorescence of digitate

spikes. Parnell.often found at the base of the sheaths themselves over

these: the latter are often conspicuous when the

former are inconspicuous—e.g.

most species of Agrostis, Avena,

Festuca, &c.

The nodes are of importance in the description of a few species only—e.g. they are usually dark coloured in certain Poas such as P. compressa and P. nemoralis; they are sharply bent in Alopecurus geniculatus, and may be so in other species if “layed" by wind, rank growth, &c.

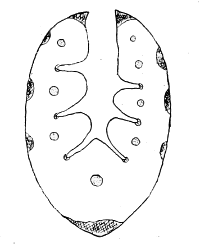

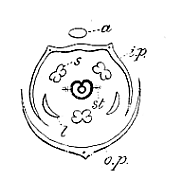

A point of considerable classificatory value is the shape of the transverse section of the shoot, which is correlated with the mode of folding up of the young leaf-blades.

In most grasses the blades are convolute—i.e. rolled up like the paper of a cigarette, one edge over the other—and the section of the shoot is round (Fig. 7). In some cases, however, the leaves are conduplicate—i.e. each half of the lamina is folded flat on the other, the upper sides being turned face to face inwards, with the mid-rib as the hinge—and in this case the shoots are more or less compressed (Fig. 6).

In these latter cases the transverse section may be

elliptical—e.g. Poa pratensis and P. alpina, Briza, &c.,

or more flattened and linear-oblong—e.g. Glyceria fluitans—with

the flattened sides straight, or the section is

oval but pointed more or less at each end owing to projecting

keels and leaf-edges, and the form is naviculate—e.g.

Glyceria aquatica, Dactylis (Fig. 6)—or, the sides being

less flattened, more or less rhomboidal as in Poa trivialis.

In Melica the leaves are convolute and the shoot-section

quadrangular.

Flat, and usually sharp-edged shoots.

Dactylis glomerata (Fig. 6).

Poa trivialis, P. annua, P. pratensis, P. compressa, P. maritima,

and P. alpina.

Glyceria aquatica and G. fluitans.

Avena pubescens.

Lolium perenne.

Fig. 6. Dactylis glomerata. Transverse section of a leaf-shoot (× 5). A, conduplicate leaf-blade. B, sheath. Stebler. |

Fig. 7. Digraphis arundinacea. Transverse section of a leaf-shoot (× 5). A, sheath. B, convolute leaves. Compare Fig. 14. Stebler. |

The leaves of all our grasses consist of the blade, which passes directly into the sheath, without any petiole or leaf-stalk (Fig. 1).

The sheath is usually obviously split, and so rolled

round the internode that one edge overlaps the other,

but in the following grasses the sheath is either quite

entire, or only slit a short way down, the two edges being

fused as it were for the greater part of its length.

Sheath more or less entire.

Glyceria aquatica and G. fluitans.

Melica uniflora and M. nutans.

Dactylis glomerata.

Poa trivialis (Fig. 8), P. pratensis, P. alpina.

Sesleria cærulea.

Bromus (all the species).

Briza media and B. minor.

In some cases—e.g. Arrhenatherum, Bromus asper, and Holcus lanatus—the sheath is marked with a more or less18 prominent ridge down its back, due to the continuation of the keel of the leaf. The sheath may also be glabrous or hairy, and grooved or not.

A few grasses are so apt to develope characteristic

colours in their sheaths, especially below, that they may

often be recognised in winter by this peculiarity.

Sheaths coloured.

Lolium—all red.

Holcus—red with purple veins.

Festuca elatior—red.

Cynosurus—yellow.

Alopecurus pratensis, and

A. agrestis—violet-brown, &c.

Festuca ovina, var. rubra—red.

Fig. 8. Poa trivialis. A, base of blade. B, ligule. C, sheath. D, culm (× about 3). |

Fig. 9. Alopecurus pratensis. A, base of blade. B, ligule. C, sheath. Slightly magnified. |

Fig. 10. Avena flavescens. Lettering as before (× 2). Note the split sheath, the hairs and ridges. Stebler. |

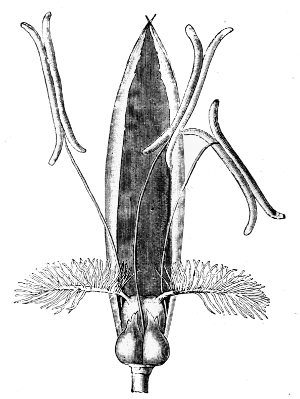

At the junction of the blade with the sheath there is in most cases a delicate membranous upgrowth of the former, more or less appressed to the stem, and called the Ligule (Figs. 8-13). Its use is probably to facilitate the shedding19 of water which has run down the leaf; and so lessen the danger of rotting between the sheath and stem: possibly the shelves and ears commonly met with at the base of the lamina (Fig. 12) aid in the same process. This ligule may be long or short, acute or obtuse, toothed or entire, or it may be reduced to a mere line, or tuft of hairs, or even be obsolete, and is of considerable value in classification—e.g. the ligule is obsolete or wanting in Melica, Festuca ovina, F. Myurus, F. elatior, Kœleria and Panicum.

It is represented by a tuft of hairs in Molinia, Triodia and Arundo.

Fig. 11. Lolium perenne. A, base of lamina, B, ligule. C, sheath (× 3). Note the low ribs, and absence of hairs (glabrous). |

Fig. 12. Festuca elatior, var. pratensis. A, base of lamina. B, the extremely short ligule, with pointed ears. C, sheath (× 3). |

Fig. 13. Festuca ovina. A, base

of lamina. B,

ligular ears. C,

sheath (× about

4). Stebler. |

Our other ordinary grasses have a more or less well-developed membranous ligule (Fig. 8).

The leaf-blade is long or short, broad or narrow, but always of some elongated form such as linear, linear-lanceolate or linear-acuminate, or subulate, setaceous, &c., varying as to the degree of acuteness of the apex, and the tapering of the base.

In the following native grasses the form of the lamina affords a useful character.

The base tapers to the sheath below—i.e. the leaf is more or less linear-lanceolate—in Molinia, Brachypodium, Melica, Milium, Kœleria, and the very rare Hierochloe; less distinctly so in Bromus asper and species of Hordeum. The base is rounded in Arundo. In the following cases the leaves are setaceous, due to the very narrow blade remaining permanently folded or inrolled at its edges, and usually being thickened and hardened also (Figs. 13 and 18). The habitat of these moor-and heath-grasses suggests that these are no doubt adaptations to prevent excessive evaporation by the exposure of too large a surface—e.g. various species of Aira, Festuca ovina, F. Myurus and allies, Nardus, and several other species; whereas, conversely, the thin flat leaves of shade-grasses facilitate exposure to light and transpiration. In Avena pratensis and Agrostis canina some of the leaves are involute and subulate, and the thickened leaves of Poa maritima also are turned up at the edges, and are U-shaped in cross-section.

As we shall see later the degree of inrolling of many grass leaves varies with circumstances.

In most others the blades are either flat (Figs. 8-12), or more or less conduplicate on the mid-rib. The latter case occurs, for example, in grasses with flattened shoots, especially at the lower part of the blade—e.g. Lolium perenne, Dactylis, Glyceria, and some species of Poa, and the cross-section of the leaf below, just before it enters the sheath, is V-shaped. In Glyceria the leaf-bases may show yellow or brownish triangles.

Further characters of the leaves are derived from their texture, apex, margins, mid-ribs and venation, hairiness, and especially the presence and characters of the longitudinal ridges which run along the upper or lower surface in many cases.

The venation is parallel from base to apex in nearly all our grasses, but such is not always the case—e.g. in the exotic Panicum plicatum the mid-rib, which enters the leaf with several vascular bundles, gives off strong and weak veins below, which first diverge and then run in arches which converge upwards: this leaf is also remarkable in being plaited (plicate) in vernation. In Arundo Donax also the veins, though approximately parallel, do not all run to the apex of the tapering leaf; the outer ones end above in the margins and are shorter than the mid-rib.

As regards texture, the leaves of most grasses are thin and herbaceous; but in some they are dry and harsh to the touch. They are thin and dry in Agropyrum caninum, Hordeum pratense, H. murinum, Avena pratensis, &c., very hard and leathery (coriaceous) in Psamma, Nardus, species of Festuca, Aira, Agropyrum junceum, Elymus, &c. In aquatic grasses like Glyceria, the leaf is almost spongy owing to the large air-chambers developed in the tissues. These are easily visible with a lens.

The apex is in most cases slender and tapering—acuminate; but in some it is merely brought to a point (acute) as in Catabrosa, Glyceria and several species of Poa and Avena, &c., usually flat, but somewhat hooded or curved up in some Poas. In cases where the leaves are setaceous or subulate, the apex is like a thin tapering22 bristle, and even flatter leaves may be so inrolled at the tips as to have the apex prolonged into a sharp needle-like pungent or spinescent point—e.g. Hordeum pratense, Avena pratensis to a slight extent, and pronounced in Elymus, &c. In Sesleria the apex is rounded with a short, sharp, prickle-like median projection (mucronate).

The passage of blade into sheath has already been described, but the base of the blade may have its margins projecting as horizontal shelves, like a Byron collar, round the sides of the throat of the sheath, sometimes tinged with yellow or pink—e.g. Lolium, Holcus, Bromus inermis, Hordeum; the ends of these may project as auricles or ears—e.g. Festuca elatior, Elymus, Agropyrum, Anthoxanthum, Bromus asper, Hordeum, &c. In Festuca ovina the ears are short, stiff, and erect (Fig. 13).

The margin may be perfectly even, as in most grasses, or it is more or less scabrid or scaberulous, as in Aira cæspitosa, Poa maritima, Festuca elatior, Avena pratensis, Agrostis, Milium, Phleum, Briza, the minute teeth (serrulæ) pointing up or down.

The surface may be bright green, or glaucous, harsh, hairy or glabrous, and is not uncommonly also scabrid, like a file or emery-paper, and sometimes only when rubbed in one direction up or down, owing to the minute teeth being directed all one way. These teeth are developed on the ridges.

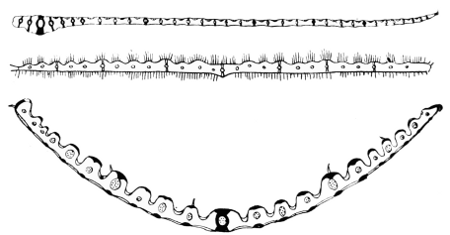

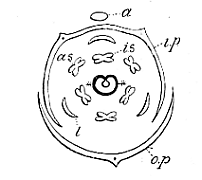

All our ordinary grass leaves are parallel-veined, and the vascular strands (the veins) can usually be seen on holding the leaf up to the light. In most cases the tissue is raised over the veins, as ridges or “ribs," and according23 to the height of these ridges the thinner parts between look like deep or shallow furrows (cf. Figs. 8-16 and Chapter IV.). If the leaf is held up to the light the ridges appear dark in proportion to their opacity—i.e. height or thickness—and the furrows light in proportion to the thinness of the tissues there. If the contrast is very great, as in Aira cæspitosa (Fig. 23), the furrows seem like transparent sharp lines, and when, as in Poa, which is practically devoid of ridges, the difference of thickness is small they appear merely as fine striæ. These characters must be determined on the fresh leaves, however, because the contraction in drying draws the ridges closer together and tends to obliterate the lines.

Fig. 14. Digraphis arundinacea. Transverse section of mid-rib and half the leaf (× about 6).

Fig. 15. Holcus lanatus. Transverse section of leaf-blade (× 10).

Fig. 16. Cynosurus cristatus. Transverse section of the leaf-blade (× 20). Stebler.

The ridges are almost always evident—Catabrosa, Poa, and Avena furnishing the chief exceptions—and are nearly invariably on the upper surface: they are below in Melica,24 however; and their relative numbers, heights and breadths, section—acute, rounded, or flattened—furnish valuable characters; as also does the coexistence or absence of hairs, asperities, &c.

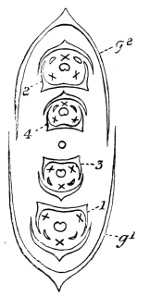

Fig. 17. Transverse section of the leaf of Festuca elatior, var. pratensis (× 12).

Fig. 18. Ditto of the leaf of F. ovina (× 15).

Fig. 19. Ditto of the leaf of F. ovina, var. rubra (× 35).

Fig. 20. Festuca ovina, var. rubra. Transverse section of the blade of an upper leaf (× 35). Stebler.

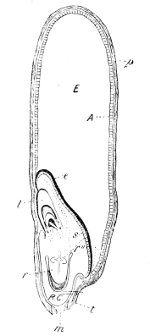

A very interesting anatomical adaptation is met with in the leaves of many grasses which grow in dry situations (xerophytes) such as on sandy sea-shores, exposed mountains and so forth. When the air is moist, in wet weather or in the dews, and the sun’s rays not too powerful, the leaf is spread out with its upper surface flat or nearly so, but when the scorching sun and dry air or winds prevail, the leaves fold or roll up, with the upper sides apposed or overlapping inside the hollow cylinder thus made.

In such leaves some of the upper epidermal cells,

either next the mid-rib (Sesleria &c.) or between the other

ribs (Festuca &c.) are large and very thin-walled, full of

sap when distended, and so placed that as they lose water

by evaporation they contract, and so draw together

the two halves of the lamina (Sesleria) or each ribbed

segment (Festuca), thus causing the infolding or inrolling

(see Chapter IV). Not only from the structure

and actions of these motor-cells, but also from the fact that

the stomata are on the upper surfaces and thus protected,

and that the lower surfaces which alone are exposed to

the drought are defended by hard and impenetrable

tissues, we must look upon these as adaptations to the

xerophytic conditions.

Leaves prominently ridged.

Elymus.

Psamma.

Aira cæspitosa.

Lolium.

Cynosurus (Fig. 16).

Agrostis.Alopecurus.

Glyceria fluitans.

Kœleria.

Festuca elatior.

Festuca Myurus (var. sciuroides).

Melica has ridges on the lower surface.

Ridges are less prominent in Phleum pratense, Briza, Agropyrum, Triodia, Arrhenatherum avenaceum.

Leaves practically devoid of ridges.

Poa—all common species.

Glyceria aquatica.

Catabrosa aquatica.

Avena pratensis.

In some grasses the tissue over the mid-rib is considerably

raised and strengthened on the dorsal side of the

blade as a “keel."

Keel more or less prominent.

Arrhenatherum (sheath keeled).

Poa (all except P. maritima).

Dactylis.

Bromus.

Bromus asper (sheath keeled, often a white line).

Holcus lanatus (slight and decurrent) (Fig. 15).

Digraphis (Fig. 14).

Glyceria.

Most grasses are glabrous, but there are a number in

which hairs are nearly always a prominent feature. It

must be remarked, however, that with grasses, as with

other plants, the character of pubescence is apt to vary

with the situation. In general it may be stated that a

hairy grass tends to become more glabrous in a moist

situation, and more pubescent in a dry one, but the rule

is by no means absolute. In some cases,—e.g. Avena

pubescens, A. flavescens, Agropyrum, the hairs are almost

entirely confined to the crests of the ridges (Figs. 10, 15).

The following is a list of hairy grasses.

Hairy Grasses.

Holcus (Fig. 15).

Molinia cærulea.

Brachypodium sylvaticum.

Agropyrum (variable).

Bromus asper.

B. mollis.Hordeum.

Anthoxanthum.

Avena flavescens (Fig. 10).

A. pubescens.

Triodia.

Kœleria.To a less extent. Festuca sciuroides (on ribs). Melica.

Grasses as a rule are devoid of strong scents5 or tastes, but Anthoxanthum has a faint but distinct sweet odour, especially as it dries—it is one of the grasses which give the scent to new-mown hay—and a bitter flavour, and Milium, Hierochloe and Holcus are also more or less bitter. Spartina stricta emits a strong unpleasant odour.

The habitat of grasses is of great importance as an aid to determination. No one would expect to find a sea-shore grass growing in a beech-forest, or an aquatic grass on a dry chalk-down; but they are even more true to their habitats than this, and I append the following lists of habitats of British grasses as of use in determining them, though it is not pretended that the limits are absolute.

In the following list “pasture-grass" (P) means useful

for grazing, and "meadow-grass" (M) one that is especially

valuable for mowing—i.e. for hay. A “weed" (W) is used

in its agricultural sense for a grass not useful and not

wanted on cultivated land, though often found there.

Meadow- and Pasture-grasses.

(P and M) Dactylis glomerata (fields, &c.).

(P and M) Poa trivialis (meadow and pasture).

(W) Bromus arvensis (cultivated and waste places, meadow and pasture).

(W) B. sterilis (ruderal).

(P and M) Poa pratensis (meadow and pasture).

(W) Briza media (meadow and pasture).

(P) Avena pratensis (meadow and pasture, especially hilly).

(P) A. pubescens (var.)—dry.

28(P and M) Lolium perenne (meadow, pasture and waste places).

(P and M) L. italicum (valuable culture grass).

(P) Cynosurus cristatus (downs).

(M and P) Festuca elatior (meadow and moist pasture, banks and river-sides).

(W) Agrostis alba and A. canina (pasture and waste places, wet or dry).

(P and M) Alopecurus pratensis (meadow and pasture).

(W) A. geniculatus (moist meadows and marshes).

(P and M) Phleum pratense (meadow and pasture).

(P) Arrhenatherum avenaceum (meadow, hedges and copse).

(P and M) Anthoxanthum odoratum (fields generally).

(W) Hordeum pratense (moist meadow and pasture).

(W) Holcus lanatus and H. mollis (meadow, pasture and waste).

(P and M) Avena flavescens (dry meadow and pasture).

(W) Avena fatua (corn-weed).

(P) Festuca ovina (light limestone pastures and chalk downs).Shade-grasses.

Found in woods, copses, &c., under shade.

Melica uniflora (woods, &c.).

Bromus asper (hedges, thickets, and edges of woods).

B. giganteus (hedges and woods).

Aira cæspitosa (moist shade and damp hedges).

Poa nemoralis (woods, shady places and damp mountain rocks).

Milium effusum (moist woods, &c.).

Agropyrum caninum (woods and shady places).

Hordeum sylvaticum (woods and copse).

Brachypodium sylvaticum (woods, hedges and thickets).

Arrhenatherum avenaceum (meadows, hedges and copse).

Festuca sylvatica (mountain woods).Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Grasses.

Found in wet ditches, ponds, and on marshes, river-banks, &c.

Glyceria fluitans (wet ditches and slow waters).

G. aquatica (wet ditches and shallow waters).

29Alopecurus geniculatus (moist meadow and marsh lands).

Digraphis arundinacea (river-banks, marshes).

Arundo Phragmites (wet ditches, marshes and shallow waters).

Molinia cærulea (wet heaths and moors, woods and waste places).

Triodia decumbens, Agrostis alba, Catabrosa and Calamagrostis.Moor-and Heath-grasses.

Downs and dry hill-pastures.

Nardus stricta (moors, heaths and hilly pastures).

Aira flexuosa (heaths and hill pastures).

Molinia cærulea (wet heathy moors, woods and waste places).

Kœleria cristata (dry pasture).

Triodia decumbens (dry heathy and hilly pastures).

Festuca ovina (hilly pastures—especially dry and open—rarer in moist situations).

Agrostis vulgaris and A. canina.Maritime or Seaside Grasses.

Poa maritima (maritime).

P. distans (sandy pastures and wastes near sea).

Elymus arenarius (coasts).

Psamma arenaria (coasts).

Poa bulbosa (waste places in S.E. of England).

Agropyrum junceum (coasts).

Hordeum maritimum (S. and E. coast).

Phleum arenarium (coasts).Ruderal or Vagabond Grasses.

Waste places, walls, road-sides and dry sandy situations.

Molinia cærulea (wet, heathy moors, woods and waste places).

Festuca Myurus (waste places, walls, road-sides).

F. ovina (hilly pastures and especially dry, rarely moist situations).

Aira caryophyllea (sandy and hilly pastures).

30Aira præcox (sandy and hilly pastures).

Poa distans (sandy wastes near the sea).

P. compressa (dry, barren, waste ground).

P. annua (cultivated and waste lands and fields).

Agropyrum repens (fields and waste places).

Hordeum murinum (waste places and road-sides).

Holcus lanatus (meadow, pasture, and waste lands).

H. mollis (same—rarer).

Alopecurus agrestis (waste lands and roads in S. of England).

Lolium perenne (meadows, pastures and waste places).

L. temulentum (fields and waste places, not common).

Bromus sterilis (on way-sides, &c.).

B. arvensis (cultivated and waste meadows and pastures).

Poa rigida (dry, rocky places).

It is also often useful to know whether a grass is rare or local, especially for the purpose we have in view, and I have therefore drawn up the following list of rare, local or introduced foreign grasses either not noticed at all, or only referred to incidentally in this work.

In many cases these introduced foreign grasses have sprung up from seeds brought over in cargoes of hay, wool, and other products and packing materials, which in part accounts for their occurrence only near certain sea-ports, manufacturing towns and so forth. Such plants are frequently termed ballast plants. Foreign plants are also introduced in seed, as mixtures or impurities, and frequently escape from corn-fields &c.

Leersia oryzoides (ditches of Hants., Sussex and Surrey).

Panicum sanguinale (S. England).

P. verticillatum (fields in S. and E.).

P. glaucum (rarely introduced).

Hierochloe borealis (Thurso only).

Phleum alpinum (Highlands only).

31P. Bœhmeri (Eastern counties, rare).

P. asperumxEas"terncou"nties"

Phalaris canariensis (rare weed).

Alopecurus alpinus (Highlands).

Mibora verna (Anglesea and Channel Islands).

Lagurus ovatus (Suffolk coasts).

Polypogon monspeliensis (rare, in S. England near sea).

P. littoralis (salt marshes S. England).

Agrostis setacea (dry heaths of S. Wales).

A. Spica-venti (sandy fields of E. counties).

Gastridium lendigerum (fields and waste places in S. Wales and Norfolk).

Calamagrostis Epigeios (moist glades &c. in Scotland).

C. lanceolata (moist shades, scattered in England).

C. stricta (bogs, &c., very rare).

Cynodon Dactylon (waste and cultivated lands near sea in Scotland).

Spartina stricta (salt marshes S. and E. coast).

Lepturus incurvatus (scattered on shores).

Bromus maximus (Jersey).

B. madritensis (roads and waste, Scotland and Tipperary).

B. inermis (introduced from Hungary).

Lolium italicum (introduced from Lombardy).

Festuca uniglumis (Irish and S.E. coast).

Poa procumbens (waste ground near sea).

P. loliacea (sandy sea-shores).

P. laxa (Ben Nevis, &c.).

P. alpina (Highlands and N.).

Catabrosa aquatica (shallow pools and ditches, scattered).

Finally, a few words may be said on a subject still in its infancy—that of Indicator-plants. In many cases certain plants are found so confined to certain classes of soil, that foresters and agriculturists have claimed to be able to infer from their presence the presence or absence of certain chemical or other constituents of soils: on the contrary we find other plants so universally distributed32 without reference to the quality of the soil, that they are not indicative. The latter are often termed ruderal or vagabonds (see p. 29). Without attempting too rigid a classification of Grasses in this connection—which would be premature in this early state of our knowledge—the following remarks are at least generally true.

A few grasses are Indicators of chalk and limestone—e.g. Briza media, Kœleria cristata, and the exotic species Stipa pennata and Melica ciliata.

The following are said to indicate a sufficiency of potassium salts,

In moister soils.

Digraphis arundinacea.

Phleum pratense.

Avena pubescens.Arundo Phragmites.

Molinia cærulea.

Glyceria fluitans.In drier soils.

Anthoxanthum odoratum.

Alopecurus pratensis.

Agrostis alba.

Holcus lanatus.

Arrhenatherum.

Kœleria cristata.

Briza media.Dactylis glomerata.

Cynosurus cristatus.

Poa pratensis.

P. trivialis.

P. compressa.

Festuca elatior.

Lolium perenne.

Grasses like Bromus arvensis indicate the existence of clay in the soil.

While the following are indicative of sand,In drier soils.

Aira caryophyllea.

A. præcox.

A. canescens.Festuca ovina.

Bromus sterilis.

And only if the sandy soil is moist and of better quality, owing to a certain proportion of humus, the following,

Anthoxanthum odoratum.

Agrostis alba.

Dactylis glomerata.Arrhenatherum avenaceum.

Avena pubescens.

Poa pratensis.

That the soil contains considerable quantities of common salt—sodium chloride—may be inferred if the following grasses occur,

Psamma arenaria.

Elymus arenarius.Hordeum maritimum.

Agropyrum junceum, &c.

The existence of much humus is indicated by such shade grasses as

Melica uniflora.

M. nutans.

Milium effusum.Bromus giganteus.

B. asper.

Brachypodium sylvaticum.

Whereas soils known as “sour," though containing much vegetable remains, may be suspected if the following grasses abound on them,

Aira cæspitosa.

Nardus stricta.Alopecurus geniculatus.

Molinia cærulea;

especially if sedges and rushes coexist with them.

When cuttings are made in forests, such grasses as the following are very apt to appear, and may do harm to young plants,

Festuca ovina and varieties.

Agrostis alba.Holcus mollis.

Aira flexuosa, &c.

The grasses more especially indicative of particular classes of forest-soils are chiefly the wood-species (see34 p. 28), and need not be further specified. In gaps, borders, and copses—half-shade—we find several common grasses—e.g.

Anthoxanthum odoratum.

Agrostis alba.

Aira flexuosa.

Holcus lanatus.

Arrhenatherum avenaceum.Triodia decumbens.

Dactylis glomerata.

Festuca rubra.

Brachypodium pinnatum.

Hordeum sylvaticum.

Whereas

Poa nemoralis,

Festuca sylvatica,

Agropyrum caninum,

Melica,Milium,

Bromus asper,

B. giganteus,

Brachypodium sylvaticum,

are more likely to be met with in the deep shade inside the forest.

On the other hand there are vagabond grasses which seem to show no signs of preference for one soil over another—e.g. Poa annua—though in some cases these ruderal plants indicate the presence of rotting substances, on ash-heaps and rubbish of various kinds.

With reference to the above, however, the student must not forget that very complex relations are concerned in changes of soil, shade, moisture, elevation, &c. and that although experienced observers can draw conclusions of some value from the presence of numerous species and individuals on a given soil, no one must conclude too readily that a soil is so and so, from observing solely that a particular kind of grass will grow there.

An excellent example of what may be done by applying such knowledge as exists of the habits of grasses, is afforded by the historic case of the planting up of shifting35 sand-dunes with species like Psamma arenaria, Elymus arenarius, Agropyrum junceum, &c. (together with sand-binding species of sedges) and so not only fixing the sand, but preparing it for gradual afforestation with bushes and eventually trees, and so saving enormous tracts of land and sums of money, as has been done on the West coasts of France.

Moreover, the action of ruderal plants—including grasses—is to completely alter the nature of the poor soil and gradually fit it for other plants. Coverings of grass greatly affect the actions of heat and sunshine on the surface soil, and modify the effects of radiation and evaporation, to say nothing of the penetrating and other effects of the roots.

Rhizomes and stolons break up stiff soils; and every engineer and forester knows how useful certain grasses are in keeping the surface-soil from being washed down by heavy rains on steep hill-sides or embankments.

On the other hand, luxuriant growths of tall grasses may do harm to young plants, by their action as weeds and especially as shade-plants; though foresters can employ them in the latter capacity, under restrictions, to shelter young trees from the sun. Again, too much dry grass near a forest offers dangers from fire; and it is a well known fact that certain injurious animals, e.g. mice and other vermin, are favoured by a covering of grass.

Graminaceæ are for the most part chalk-fleeing plants, in spite of the fact that certain species can grow in very thin layers of soil on chalk downs. They must be regarded as requiring moderate supplies of humus as a36 rule, and even sand-loving grasses are not real exceptions.

The physiognomy of the grasses has always been regarded as a striking one, and Humboldt classed it as one of his 19 types of vegetation. As is well known they are sociable plants, often covering enormous areas—prairies, alps, steppes, &c.—with a few species, alone or densely scattered throughout a mixed herbage. They also represent characteristically the sun-plants, the erect leaves exposing their surfaces obliquely to the solar rays, and being often folded and nearly always narrow.

The dead remains of these sociable grasses are an important factor in protecting the soil against drought and in facilitating humification, as well as in covering up plants during long winters or dry seasons, keeping the ground warmer and moister, and generally lessening the effect of extremes.

Many Graminaceæ are pronounced xerophytes, the epidermis often being developed as a water-storing tissue, while the erect leaves roll themselves in intense light, the stomata being situated accordingly. The halophytic strand-plants Psamma arenaria, Elymus arenarius, Agropyrum junceum, and other Dune-species, as well as species of Aira, Festuca, Anthoxanthum, Stipa, Lygeum, Aristida, &c. are examples. The heath-grasses—e.g. Festuca ovina, Nardus stricta, Molinia cærulea—also come under this category.

Many of the strand-plants (halophytes) Agropyrum, Psamma, Elymus, are covered with waxy bloom, and have long rhizomes which bind the sand and form new soil, a37 property largely taken advantage of in certain forest operations.

Other grasses, particularly annual species, show their adaptation to xerophytic habits by forming bulbous store-houses at the base of the culms—e.g. Phleum arenarium.

Some Graminaceæ are hydrophytes, such as Arundo, Glyceria, &c., with large intercellular spaces in their tissues; while many species—e.g. Aira cæspitosa, Agrostis canina, Molinia cærulea—grow on wet moor-lands, forming perennial tufts, with or without creeping rhizomes.

The mesophyte grasses are especially characteristic of what may be termed carpets—a lawn is a good example on a small scale, though of course we must remember that here the struggle for existence has been artificially interfered with more or less. Such carpets consist of the densely interwoven rootlets and rhizomes forming sod, and contain much humus from the accumulated débris of former years. These grass-carpets may be composed of nearly pure growths of a few species, or of very many different grasses and other herbage. They are common in Arctic regions, on Alps, and in temperate climates generally, where we know them as meadows, hay-fields, pasture and lawns.

The Bamboos in the wider sense have a physiognomy of their own, e.g. in India, and may drive out most other plants and form dense undergrowths or jungle of interlaced stems and leaves and thorny shoots. Similar growths occur on the Andes and elsewhere in South America. In some parts of India and tropical Asia the taller bamboos form aggregates comparable to dense forests, and such forests are common on the banks of several large tropical38 rivers. Most of these Bamboos are xerophytes. Bamboos are neither confined to the tropics, nor to warmer regions, however, for species are known from distinctly cool regions—e.g. South America—or even from near the snow line—e.g. Chili, the Himalayas, Japan, &c., and the number of species known as hardy is increasing annually, as is evident on examining our larger English gardens.

The permanence and character of extensive grasslands, especially prairies, savannahs, and steppes, are much affected by the periodical firing they are exposed to in the dry season, and large tracts of country in various parts of the world would doubtless bear forests or other vegetation if not thus fired, while in other cases the herbage would be differently constituted were firing discontinued.

The following chapter embodies an attempt to classify our British grasses solely for purposes of identification when not in flower. It is not claimed that the arrangement is the best possible, nor that it is complete, and I need hardly say that corrections will be gratefully received.

I. Sheaths entire except where those of lower leaves are burst by branches, &c.

A. Aquatics with the sheaths reticulated, owing to large air-cavities. Leaves equitant, linear acute, often floating.

Glyceria fluitans (Br.). Floating sweet grass. Somewhat coarse, but useful pasture in water-meadows and fens. Sweet-tasting.

Section of sheathed leaves linear oblong; sheath striate or furrowed, keeled; leaf ribbed; ligule broad acute. Leaf-base with a yellow triangle. Smooth.

Glyceria aquatica (Sm.). Reed sweet grass. Especially given to growing in the water-courses and on banks instead of spreading in the water-meadows, &c. Sweet-tasting.

Section of sheathed leaves broadly naviculate; sheath smooth, no keel; leaf not ribbed, thick and inflated with 40 large air-cavities; ligule short. Leaf-base with a brown triangle. Margins and keel rather rough.

These two species of Glyceria are distinguished by their shoot-sections and the ridges of the leaves of G. fluitans: they often occur in the same ditch.

They cannot readily be confused with others on account of their aquatic habit, and the characters given. The only other aquatic or semi-aquatic species are forms of Catabrosa, Digraphis, Arundo, Alopecurus geniculatus, Molinia cærulea and the rare Calamagrostis.

The ligule and flat shoots with closed sheaths alone suffice to distinguish it from the round and split sheathed Arundo Phragmites; and the round shoots of Digraphis, its split sheath and firm leaves, suffice to distinguish it.

Molinia also has a tuft of hairs instead of a ligule, and a split sheath, and its habit is different.

Alopecurus geniculatus, with its “kneed" shoots, has a totally different habit from Glyceria, and its very high ridges and want of visible air-chambers complete the diagnosis.

Catabrosa is a small creeping aquatic with very flaccid leaves, quite glabrous and soft. Also sweet-tasting.

B. Not aquatic, and devoid of visible air-chambers in leaf or sheath. Often perennial, i.e. having stolons or other branches with no rudiments of flowers in them, and with relics of old leaf-bases.

(α) Sections of sheathed leaves acute: either two-edged or four-edged.

(1) Section of sheathed leaves quadrangular. Blades of leaf thin and dry, sparsely hairy. Sheath quite entire. Woods and shady places.

Melica uniflora, L. (Wood Melick). Lamina slightly tapered below, convolute. Ligule obsolete, with a stiff subulate process on the sheath opposite the blade-insertion. Ridges below, but not above.

Melica nutans, L. (Mountain Melick). Ligule longer, and without the awl-shaped peg. Only in Scotland and W. of England.

Both are shade grasses of no agricultural value.

M. uniflora, with its quadrangular shoots and anti-ligular peg, cannot be confounded with any other grass.

(2) Sections of sheathed leaves more or less acutely two-edged, owing to the keels of the compressed equitant leaves.

(i) Shoots broad and fan-like, much compressed, with old brown leaf-sheaths below, sometimes burst by the intra-vaginal branches: leaf ridgeless, with prominent keel. No underground stolons.

Dactylis glomerata, L. (Cock’s-foot). An early and quick-growing pasture-grass, which forms much aftermath. Grows on all soils. Often coarse. Coarse tussocks, and harsh, with broad thick succulent bluish-green leaves.

Section of sheathed leaves acutely naviculate. Prominent obtuse ligule, torn above. Lamina long, rough, acute, with white lines if held up, and serrulate edges. No flanking lines6. No stolons (Fig. 6).

There is a cultivated variety of Dactylis with broad opaque white stripes down the leaves: these are totally different from the translucent white stripes seen on holding the wild form, or Aira cæspitosa, up to the light. Another cultivated “ribbon-grass"—Digraphis—has round shoots, split sheaths, and a different habit, and the same applies to its wild form.

Probably the only serious chances of confusion with Dactylis are between it and Poa pratensis, which also has flattened shoots and closed sheath; but in the latter the section of the shoot is elliptical—not naviculate,—the keel is far less prominent, and the ligule 42 shorter. Moreover P. pratensis is a creeping stoloniferous grass, less harsh, and with less pointed leaves.

The distance to which the sheath is torn may be from 1/8 to 1/2 down. Leaves tend to remain conduplicate. Margins serrulate with teeth extremely short and directed forwards.

(ii) Shoots compressed but narrow: the section almost

rhomboid with rounded edges.

Poa trivialis, L. (Rough-stalked Meadow-grass). Conspicuous in deep rich pastures and orchards, preferring slight shade and rich soil. Valuable pasture and hay grass.

Rootstock shortly creeping, branches extra-vaginal and above ground, shoots rough. Blade narrow, harsh, with an acute point, thin, shining below, ridgeless, with flanking lines and keel. Ligule acute, and short or long (Fig. 8).

Sesleria cærulea, Ard. (Blue Moor-grass), of our northern limestone hills, has narrow, flat, glaucous blue, stiff, mucronate leaves, with scabrid apex. Ligule ciliate.

Poa trivialis is most likely to be confounded with other Poas, especially P. annua and P. pratensis, since they both have thin leaves and flat shoots; but P. annua has a split sheath, less acute and duller leaves, is annual, and less harsh, and the shoot-section is flatter at the sides and rounder at the ends.

Poa pratensis, L. is larger and more stoloniferous, with both extra- and intra-vaginal branches, culms erect and smooth, sheaths smooth, and the shoot-sections elliptical—not cornered or rhomboidal—and with darker green and larger, thicker, 7-veined, more glossy, and less harsh leaves, with shorter, blunter ligule.

Poa compressa, L. also presents difficulties, but the sheath is split, and the ligule is shorter than in P. trivialis, the leaves thicker, and the shoot-sections more linear-oblong or elliptical.

(β) Sections of sheathed leaves rounded, circular or oval, there being no prominent keels.

(1) Section of sheathed leaves circular or nearly so, the shoots being only slightly compressed.

✲ Perennial.

Bromus inermis (Awnless Brome).

Sections circular, the leaves being convolute, base shelving. Glabrous sheaths and leaves. Stoloniferous. Ligule short, truncate, and finely toothed. A forage grass of the Hungarian steppes. Now being grown in this country, but of doubtful value here.

Bromus erectus, Huds. (Upright Brome). A weed.

Sections oval and rounded, but leaves equitant. Radical leaves remain folded and almost subulate, hairy edges. No stolons. Fields, &c. It is a weed on dry lands, and of little or no value.

Bromus asper, Murr. (Hairy Brome). In thickets, &c.: a weed, and useless. Leaves green, long, flat, hanging, and eared. Sheath with scattered deflexed hairs. Lamina tapering at the base. Keel a white line, ridges inconspicuous: distance between veins 2-3 times breadth of latter. Ligule very short, toothed.

B. giganteus, L. (Tall Brome), also comes here. It is less common and glabrous. Woods, &c., a useless weed.

✲✲ Annual or biennial.

Bromus mollis (B. arvensis, var. mollis, L.), Field Brome. A too abundant and useless weed in water-meadows and hay-fields. Softly downy. Blades very thin and not eared: dry.

Bromus sterilis, L. (Barren Brome). A useless weed. Rough and downy, but less so than the last. Moist waysides, &c.

The Bromes are extremely variable and difficult to determine by the leaves. The annual species are apt to be biennial or (B. sterilis) perennial; and some vary much as regards hairiness—e.g. B. mollis is connected by a series of semi-glabrous forms to varieties quite smooth, all grouped by Bentham under B. arvensis.

Bromus asper, being auriculate and a shade-species, runs some risk of confusion with Hordeum sylvaticum, but Hordeum has a split sheath and in B. asper the translucent interspace between the ridges is 2-3 times as broad as in Hordeum sylvaticum.

The other species of Bromus are not eared, and their entire sheaths at once distinguish them from Hordeum.

Bromus giganteus has leaves glabrous and very like Festuca elatior. The red split sheaths of the latter, its sharp ears and prominent ridges afford the best distinctions; and B. giganteus has broader leaves and more evident serrulation or descending bristles at the basal margins.

(2) Section of sheathed leaves elliptical, owing to the shoots being compressed. Sheaths often only slightly split above. No hair on surface of leaves or sheaths.

✲ Margins of leaves smooth and even. Blades without ridges, a keel and flanking lines, acute, base rounded. Ligule of lower leaves very short.

Poa pratensis, L. (Smooth-stalked Meadow-grass). An early and valuable dry pasture-grass, but though deep-rooted, it yields thin hay: its chief value is for "bottom grass" and in lawn mixtures, &c. Leaves stiff and pointed. Extra-vaginal rooting underground stolons, and intra-vaginal branches. Shoots smooth. Keel slight: seven principal veins and smaller ones between. Leaves blunter and broader than in P. trivialis.

Poa alpina, L. (Alpine Poa). On mountains in the north. No stolons. 4-5 veins on each side of the median one.

Poa pratensis presents similar difficulties to P. trivialis: for diagnoses see p. 42. It is distinguished from P. nemoralis by its closed sheath, thicker, blunter and harder leaves, linear-elliptical shoot-sections, and light coloured nodes, as well as by its habit. All other Poas have shallow and poorly developed roots.

P. fertilis is a form very like P. nemoralis, with rougher leaves and longer ligule, introduced into cultivation.

✲✲ Margins of leaves scaberulous with descending hairs. Very low flat ridges. Sheath smooth.

Briza media, L. (Quaking Grass). A weed in meadows, indicating poor soil—e.g. moorlands and chalk—but eaten by sheep. Tufted and slightly creeping perennial. Ligules very short, entire.

Briza minor, L. (Lesser Quaking-grass). Annual. Leaves broader and shorter, and ligules longer. In the south and rarer.

II. Sheaths split, at least some distance down.

A. Glabrous—i.e. with no obvious hairs7.

(a) Grasses with setaceous or bristle-like leaves;—i.e. the lamina of the lower leaves remains permanently folded instead of opening out flat.

(1) Ligule obsolete, auricled at the junction of blade and sheath.

Festuca ovina (Sheep’s Fescue). Densely tufted perennial. Leaves hard, glabrous and often glaucous, with 5-7 ridges if forcibly unrolled, ears short, stiff and erect. Branches in permanent sheaths. Chiefly useful as pastures 46 on downs and dry chalk-soils. Several varieties are recognised by agriculturists, as hard, red, various-leafed, fine-leafed Fescue, &c. (see Figs. 13 and 18).

Festuca Myurus, L. (Rat’s-tail Fescue). Annual, longer auricles, and hair on the ribbed inrolled surface. A roadside weed.

Festuca ovina presents difficulties with its varieties and with F. Myurus, L. (var. sciuroides, Roth.).

The chief varieties of F. ovina are Hard Fescue (F. duriuscula, L.), taller and with some of the upper leaves flat, and found in moister and rich soils: Red Fescue (F. sabulicola, Duf. or F. rubra, L.) more or less creeping and with red sheaths to the lower leaves, on poor stony land—F. heterophylla is a form of this on chalky soils, with flat leaves above: and F. tenuifolia a very wiry form on sheep-lands. They all pass into one another, however, and cannot be distinguished by the leaves (see Figs. 18-20).

F. Myurus (var. sciuroides) is ruderal and annual, and has longer hairs on the ridges of the folded leaves. It has no agricultural value.

(2) Ligule membranous, not auricled.

(α) Bristle-like (setaceous) leaves, very hard and stiff, and more or less solid.

Nardus stricta, L. (Moor Mat-grass). Roots very tough and stringy: ligule small, but thick and blunt. Leaves channelled: upper erect, lower horizontal. Sheath smooth. Moors and sandy heaths: useless (Figs. 2 and 26).

Aira flexuosa, L. (Wavy Hair-grass). Roots fibrous. Leaves short, filiform, terete, solid—the channel hardly discernible. Ligule short, obtuse. Heaths, &c. Of little use, even for sheep (Fig. 28).

(β) Leaves bristle-like, but distinctly due to inrolling of edges.

Aira caryophyllea, L. (Silvery Hair-grass), is scabrid. A weed, with very slight foliage.

A. præcox, L. (Early Hair-grass). Greener and more glabrous. Habit more rigid.

A. canescens, L. (Grey Hair-grass). Glaucous or purplish; rare, on S.E. coasts.

(γ) Leaves narrow and more or less involute, and subulate upwards, but easily unrolled, and apt to become flatter as they age.

Avena pratensis, L. (Perennial Oat). Leaves rather thin, dry, harsh, ridgeless, with flanking lines and a keel8; glaucous, glabrous, but edges scabrous. Usually involute, but may open out. Ligule long ovate-acute. Dry pastures, especially on calcareous soil, and of little value.

Poa maritima, Huds. (Sea-grass). Leaves narrow, rather short, and U-shaped in section. Involute: ridgeless, with flanking lines, but no keel; soft and rather thick. Ligule rather long, obtuse and decurrent. Useless agriculturally.

For difficulties with other species of Avena and Poa see pp. 44, 54 and 60.

(b) Grasses with the leaves expanded, more or less flat.

(1) Blades conspicuously ridged—i.e. the surface is raised in prominent longitudinal ridges with furrows between.

(i) Leaves rigid and hard, sharp pointed. Sheath and outer leaf-surface usually glabrous.

Aira cæspitosa, L. (Tufted Hair-grass). Forms large tufts. A coarse weed forming bad tussocks in wet meadows and pastures: useless for fodder. Leaves flat. Ligule long, acute. Ridges equal, high and sharp, and scabrid, 48 with 5-6 white lines between, if viewed by transmitted light. Wet meadows.

A. cæspitosa cannot easily be mistaken for any other species. Alopecurus geniculatus is also a moisture-loving grass with strongly ridged leaves, but the interspaces are far less translucent and the whole habit is different.

All the other species of Aira have involute and setaceous leaves, and even A. cæspitosa is apt to roll in its leaves in mountain varieties, but they are easily flattened out, and show the ridges.

Psamma arenaria, Beauv. (Sea Mat-grass). This is one of the most valuable “sand-binders," its long matted rhizomes holding loose sand together. It is a sea-shore grass, of no use for fodder. It was formerly much used for mats and thatching. Leaves concave, long, narrow, erect, scabrid and glaucous above, and polished below: pungent. Ridges rounded, alternately high and low. Sheath long. Ligule very long and bifid.

Elymus arenarius, L. (Sand Lyme-grass). Like Psamma, this is a “sand-binder" and of no use for fodder. Leaves concave, and eared at the base of the blade: ears pointed and tend to cross in front. Ligule very short and obtuse. Ridges flattened above, not scabrid. Apex of blade rolled, forming a hard spine.

Psamma cannot easily be mistaken for the much less common Elymus, as it is not eared, and the ridges and ligule are very different.

(ii) Leaves not specially rigid and hard, and often thin; glabrous, or shining below. Ridges less evident.

✲ Ligule very short or obsolete; blade firm but not hard, glabrous or nearly so, and shining below. Sheath often coloured red or yellow at the base.

† Sections of sheathed leaves narrow, oblong, owing to compression of shoots. Sheath nearly entire.

Lolium perenne, L. (Perennial Rye-grass). Very valuable pasture-grass, especially on clay. Less successful as hay. Deep rooted tufts. Glossy dark green. Ligule short (Fig. 11). Sheath red or purplish below. Blade conduplicate and keeled, often rounded, collared or eared at the base; with rounded ridges and rough above, shining below. When the ears are well developed their points often cross one over the other in front of the sheath.

L. italicum, Braun. (Italian Rye-grass), is an earlier and better variety for hay and sewage farms. Shoot more rounded in section, and has less marked veins on the more rolled leaf.

L. temulentum, L. (Common Darnel), is annual and a weed of corn-fields. Foliage usually rougher.

Lolium perenne presents some difficulties in relation to such forms as L. italicum, species of Agrostis and Festuca, Alopecurus pratensis, Cynosurus and Agropyrum.

Owing to the leaves not being always strictly conduplicate in the first year, the flat shoots may not sharply mark it off from L. italicum. Its somewhat looser, almost stoloniferous tufts, and darker green foliage, less polished below and usually narrower and harder, have then to be taken into account.

The ridges of Lolium are often like those of Festuca pratensis; and the shining lower surface and rather firm leaves and red sheaths, present other points of confusion. The smooth basal margins of Lolium, absence of white translucent lines when held up, and the different ligule and ears afford distinctions—the ligule of Festuca being a mere line, and the ears pointed and projecting, whereas they may be mere lateral ledges in Lolium.

Cynosurus has the ligule and ears very like those of Lolium, the ears being mere ledges; but the former has yellow sheaths, firmer and thicker leaves with more evident ridges, and the old plants usually have the characteristic crested spikes remaining. Cynosurus, moreover, has the sheath split only a short way down.

With regard to Agrostis, there is no colour in the sheath, the ligule is longer and pointed, and the leaves drier and thinner than in Lolium, and harsher on both surfaces. Agrostis has also no ears.

Alopecurus pratensis has much broader and flatter ridges than Lolium and a longer ligule, and its sheaths are dark-brown or black—not red; but A. agrestis has very similar ridges to Lolium and may easily be confounded at first.

Agropyrum is sometimes nearly glabrous, and may then be confused with Lolium by beginners: its low ridges, curled and pointed ears, obsolete ligule, and thinner, drier, harsher blade, as well as the stolons, distinguish it.

Lolium temulentum and Hordeum murinum occasionally cause difficulty, but the latter is always more or less hairy, its blades thinner and drier, and the ridges less raised.

†† Sections rounded—elliptical or nearly circular. Sheath distinctly split, at least above.

Cynosurus cristatus, L. (Crested Dog’s-tail). Useful as pasture on dry soils, but only moderately so as hay. Blade narrow, slightly eared or collared below, tapered above; firmer than Lolium. Sheath only split a short way down. Yellow or yellowish-white at the base. Leaves conduplicate or convolute, short and narrow, the ligule short: minute ears at base. Usually easily recognised by the withered culms and persistent pectinate spikes (Fig. 15).

Festuca elatior, L. (Meadow Fescue). A valuable meadow and pasture grass, though somewhat coarse. Several varieties are known. Best on heavy soils. Deep rooted. Blade flat and broad, conduplicate, sharp-eared at the base, and there rough at the margin: lower surface polished. Rich green. Mid-rib flat above, numerous ribs with white lines between if held up and examined with a lens. Ligule obsolete (Figs. 12 and 17).

Arundo Phragmites, L. (Common Reed). A large aquatic, reed-like creeping grass, with broad leaves (3/4 to 1 in.), flat, rather rigid, acuminate, glaucous below, hispid at edges. Sheath smooth, striate, bearded at mouth. Ligule a mere fringe of hair. (Cf. Digraphis, p. 54.)

Cynosurus is not very liable to confusion; but it has resemblances to Lolium (see p. 49) and to species of Agrostis. The leaves of Cynosurus are firmer, thicker, less dry, and with a shining undersurface, and the sheath is only split above, and yellow below; whereas Agrostis has relatively thin and dry leaves, rough surfaces and margin, distinct ridges, and converging margins as the blade nears the sheath.

Festuca elatior is easily confused with the glabrous Bromes. For B. giganteus see p. 43.

Bromus erectus is distinguished by the entire sheath, usually hairy, the want of auricles, and the conduplicate—not convolute—leaves.

Agrostis has thinner, duller, and drier leaves, and no red sheath.

Alopecurus pratensis has more depressed, flatter and broader ridges than Festuca, and a longer ligule, and lacks the pointed ears.

✲✲ Ligule whitish, membranous, long, or at least well developed. Sheaths not coloured or brown. Leaves thin and rough, at least at the base. Ridges not very prominent, but numerous and distinct.

Agrostis stolonifera, L. (Fiorin). Stolons, with numerous short offsets bursting through the leaf-sheaths. Blade flat, rough, tapering, with rounded ridges, and convolute in bud: there are no auricles, but the blade may narrow, and form ledges, as it runs into the sheath. Sheaths nearly smooth. Ligule long and pointed, and often toothed at the margins. The leaves vary in breadth.

This and A. vulgaris, With. with shorter ligules, and, possibly, A. canina, L. with finer leaves, are varieties of52 A. alba, L. Only the variety A. stolonifera is of moderate value for pasture, especially on poor soils, as it lasts late into autumn: the others are weeds, like couch-grass.

Agrostis is full of difficulties for the beginner. The weed-forms often spring up after wheat has been cut, and count as “twitch," like Agropyrum.

All the ordinary forms—A. stolonifera, A. vulgaris, and A. canina—may be included in A. alba (Linn.). On dry hills a close tufted grass, with setaceous leaves, and in rich soils creeping and luxuriant with broad leaves. It is one of the few grasses that thrive in wet soils.

The chief points in the flat-leafed forms are the thin, dry leaves, rough on both sides and on the margins, with distinct raised ridges, and the base of the leaf narrowing suddenly into its insertion with the sheath, with no auricle, but with a long membranous ligule. The sheath not coloured, and the blade convolute.

Again, A. stolonifera has a long, serrated, acute ligule, while A. vulgaris has a much shorter, entire and truncate one, and narrower leaves.

Agropyrum is the grass most likely to lead to confusion. Its ears, lower ridges, very short or obsolete ligule, and pubescence (sometimes glabrous) distinguish it.

Cynosurus sometimes gives trouble (see p. 50) with Alopecurus pratensis: the sheaths, ligule and flattened ridges should suffice for distinction.

Alopecurus geniculatus is even more like Agrostis, but its ridges are more prominent and sharp, and its aquatic habit and bent "knees" distinguish it.

Alopecurus agrestis, in dry corn-fields, has a thickened ligule, sometimes coloured, and is annual or biennial, but otherwise very like Agrostis.