GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XLI. November, 1852. No. 5.

Table of Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

AGATHA.

THE CASTLE OF INDOLENCE.

POETRY BY CHARLES MACKAY.

ACCOMPANIMENTS BY SIR H. R. BISHOP.

Air “Pray, Goody, PLEASE TO MODERATE.”

Oh! youth’s fond dreams, like eve ’ning skies,

Are tinged with colours bright,

Their cloud-built halls and turrets rise

In lines of ling’ ring light;

Airy, fairy,

In the beam they glow,

As if they’d last

Thro’ ev’ry blast

That angry fate might blow;

But Time wears on with stealthy pace

And robes of solemn grey.

And in the shadow of her face

The glories fade away.

But not in vain the splendours die,

For worlds before unseen

Rise on the forehead of the sky

Unchanging and serene.

Gleaming,—streaming,

Thro’ the dark they shew

Their lustrous forms

Above the storms

That rend our earth below.

So pass the visions of our youth

In Time’s advancing shade;

Yet ever more the stars of Truth

Shine brighter when they fade.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XLI. PHILADELPHIA, November, 1852. No. 5.

Those little curly-pated elves,

Blest in each other and themselves,

Right pleasant ’tis to see

Glancing like sunbeams in and out

The lowly porch, and round about

The ancient household tree.

And pleasant ’tis to greet the smile

Of her who rules this domicile

With firm but gentle sway;

To hear her busy step and tone,

Which tell of household cares begun

That end but with the day.

’Tis pleasant, too, to stroll around

The tiny plot of garden ground,

Where all in gleaming row

Sweet primroses, the spring’s delight,

And double daisies, red and white,

And yellow wall-flowers grow.

What if such homely view as this

Awaken not the high-wrought bliss

Which loftier scenes impart?

To better feelings sure it leads,

If but to kindly thoughts and deeds

It prompt the feeling heart.

———

BY THOMAS MILNER, M. A.

———

Rivers constitute an important part of the aqueous portion of the globe; with the great lines of water, with streams and rivulets, they form a numerous family, of which lakes, springs, or the meltings of ice and snow, upon the summits of high mountain chains, are the parents. The Shannon has its source in a lake; the Rhone in a glacier; and the Abyssinian branch of the Nile in a confluence of fountains. The country where some of the mightiest rivers of the globe have their rise has not yet been sufficiently explored to render their true source ascertainable. The origin of others is doubtful, owing to a number of rills presenting equal claims to be considered as the river-head; but many are clearly referable to a single spring, the current of which is speedily swelled by tributary waters, ultimately flowing in broad and deep channels to the sea. Inglis, who wandered on foot through many lands, had a fancy, which he generally indulged, to visit the sources of rivers, when the chances of his journey threw him in their vicinity. Such a pilgrimage will often repay the traveler, by the scenes of picturesque and secluded beauty into which it leads him; and even when the primal fount is insignificant in itself, and the surrounding landscape exhibits the tamest features, there is a reward in the associations that are instantly wakened up—the thought of a humble and modest commencement issuing in a long and victorious career—of the tiny rill, proceeding, by gradual advances, to become an ample stream, fertilizing by its exudations and rolling on to meet the tides of the ocean, bearing the merchandise of cities upon its bosom. The Duddon, one of the most picturesque of the English rivers, oozes up through a bed of moss near the top of Wrynose Fell, a desolate solitude, yet remarkable for its huge masses of protruding crag, and the varied and vivid colors of the mosses watered by the stream. Petrarch’s letters and verses have given celebrity to the source of the Sorques—the spring of Vaucleuse, which bursts in an imposing manner out of a cavern, and forms at once a copious torrent. The Scamandar is one of the most remarkable rivers for the grandeur of its source—a yawning chasm in Mount Gargarus, shaded with enormous plane-trees, and surrounded with high cliffs from which the river impetuously dashes in all the greatness of the divine origin assigned to it by ancient fable. To discover the source of the Nile, hid from the knowledge of all antiquity, was the object of Bruce’s adventurous journey; and we can readily enter into his emotions, as he stood by the two fountains, after the toils and hazard he had braved. “It is easier to guess,” he remarks, “than to describe the situation of my mind at that moment—standing in that spot which had baffled the genius, industry, and inquiry of both ancients and moderns, for the course of three thousand years. Kings had attempted this discovery at the head of armies; and each expedition was distinguished from the last, only by the difference of the numbers which had perished, and agreed alone in the disappointment which had uniformly, and without exception, followed them all. Fame, riches and honor, had been held out for a series of ages to every individual of those myriads these princes commanded, without having produced one man capable of gratifying the curiosity of his sovereign, or wiping off this stain upon the enterprise and abilities of mankind, or adding this desideratum for the encouragement of geography. Though a mere private Briton, I triumphed here, in my own mind, over kings and their armies; and every comparison was leading nearer and nearer to presumption, when the place itself where I stood—the object of my vain-glory—suggested what depressed my short-lived triumphs. I was but a few minutes arrived at the sources of the Nile, through numberless dangers and sufferings, the least of which would have overwhelmed me, but for the continual goodness and protection of Providence: I was, however, but then half through my journey; and all those dangers, which I had already passed, awaited me again on my return. I found a despondency gaining ground fast upon me, and blasting the crown of laurels I had too rashly woven for myself.” Bruce, however, labored under an error, in supposing the stream he had followed to be the main branch of the Nile. He had traced to its springs the smaller of the two great rivers which contribute to form this celebrated stream. The larger arm issues from a more remote part of Africa, and has not yet been ascended to its source.

Upon examining the map of a country, we see many of its rivers traveling in opposite directions, and emptying their waters into different seas, although their sources frequently lie in the immediate neighborhood of each other. The springs of the Missouri, which proceed south-east to the Gulf of Mexico, and those of the Columbia, which flow north-west to the Pacific Ocean, are only a mile apart, while those of some of the tributaries of the Amazon, flowing north, and the La Plata, flowing south, are closely contiguous. There is a part of Volhynia, of no considerable extent, which sends off its waters, north and south, to the Black and Baltic seas; while, from the field on which the battle of Naseby was fought, the Avon, Trent, and Nen receive affluents, which reach the ocean at opposite coasts of the island, through the Humber, the Wash, and the Bristol Channel. The field in question is an elevated piece of table-land in the centre of England. The district referred to, where rivers proceeding to the Baltic and the Euxine take their rise, is a plateau about a thousand feet above the level of the sea. The springs of the Missouri and the Columbia are in the Rocky Mountains; and it is generally the case, that those parts of a country from which large rivers flow in contrary directions, are the most elevated sites in their respective districts, consisting either of mountain-chains, plateaus, or high table-lands. There is one remarkable exception to this in European Russia, where the Volga rises in a plain only a few hundred feet above the level of the sea, and no hills separate its waters from those which run into the Baltic. The great majority of the first-class rivers commence from chains of mountains, because springs are there most abundant, perpetually fed by the melting of the snows and glaciers. They have almost invariably an easterly direction, the westward-bound streams being few in number, and of very subordinate rank. Of rivers flowing east, we have grand examples in the St. Lawrence, Orinoco, Amazon, Danube, Ganges, Amour, Yang-tse-Kiang, and Hoang Ho. The chief western streams are the Columbia, Tagus, Garonne, Loire and Neva, which are of far inferior rank to the former. The rivers running south, as the Mississippi, La Plata, Rhone, Volga and Indus, are more important, as well as those which proceed to the north, as the Rhine, Vistula, Nile, Irtish, Lena and Yenisei. The easterly direction of the great rivers of America is obviously due to the position of the Andes, which run north and south, on the western side of the continent, while the chain of mountains which traverses Europe and Asia, from west to east, cause the great number of rivers which flow north and south. In our own island, the chief course of the streams is to the east. This is the case with the Tay, Forth, Tweed, Tyne, Humber and Thames, the Clyde and Severn being the most remarkable exceptions to this direction. The whole extent of country from which a river receives its supply of water, by brooks and rivulets, is termed its basin, because a region generally bounded by a rim of high lands, beyond which the waters are drained off into another channel. The basin of a superior river includes those of all its tributary streams. It is sometimes the case, however, that the basins of rivers are not divided by any elevations, but pass into each other, a connection subsisting between their waters. This is the case with the hydro-graphical regions of the Amazon and Orinoco, the Cassiaquaire, a branch of the latter, joining the Rio Negro, an affluent of the former. The vague rumors that were at first afloat respecting this singular circumstance, were treated by most geographers with discredit, till Humboldt ascertained its reality, by proceeding from the Rio Negro to the Orinoco, along the natural canal of the Cassiaquaire.

Rivers have a thousand points of similarity, and of discordance. Some exhibit an unbroken sheet of water through their whole course, while others are diversified by numerous islands. This peculiarly characterizes the vast streams of the American continent, and contributes greatly to their scenical effect, of which our illustration gives us an example, selected from the beautiful Susquehanna, the largest Atlantic river of the United States. The St. Lawrence, soon after issuing from the Lake Ontario, presents the most remarkable instance to be found of islands occurring in a river channel. It is here called the Lake of the Thousand Islands. The vast number implied in this name was considered a vague exaggeration, till the commissioners employed in fixing the boundary with the United States actually counted them, and found that they amounted to 1692. They are of every imaginable size, shape, and appearance; some barely visible, others covering fifteen acres; but in general their broken outline presents the most picturesque combinations of wood and rock. The navigator in steering through them sees an ever-changing scene, which reminds an elegant writer of the Happy Islands in the Vision of Mirza. Sometimes he is inclosed in a narrow channel; then he discovers before him twelve openings, like so many noble rivers; and soon after a spacious lake seems to surround him on every side. River-islands are due to original surface inequalities, but many are formed by the arrest and gradual accretion of the alluvial matter brought down by the waters.

The Susquehanna.

There is great diversity in the length of rivers, the force of their current, and the mass and complexion of their waters; but their peculiar character is obviously dependent upon that of the country in which they are situated. As it is the property of water to follow a descent, and the greatest descent that occurs in its way, the course of a river points out generally the direction in which the land declines, and the degree of the declination determines in part the velocity of its current, for the rapidity of the stream is influenced both by its volume of water and the declivity of its channel. Hence one river often pours its tide into another without causing any perceptible enlargement of its bed, the additional waters being disposed of by the creation of a more rapid current, for large masses of water travel with a swift and powerful impetus over nearly a level surface, upon which smaller rivers would have only a languid flow. In general, the fall of the great streams is much less than what would be supposed from a glance at their currents. The rapid Rhine has only a descent of four feet in a mile between Shaffhausen and Strasburg, and of two feet between the latter place and Schenckenschauts; and the mighty Amazon, whose collision with the tide of the Atlantic is of the most tremendous description, falls but four yards in the last 700 miles of its course, or one-fourth of an inch in 1¼ mile. In one part of its channel the Seine descends one foot in a mile; the Loire, between Pouilly and Briare, one foot in 7,500, and between Briare and Orleans one foot in 13,596; the Ganges, only nine inches; and, for 400 miles from its termination, the Paraguay has but a descent of one thirty-third of an inch in the whole distance. The fall of rivers is very unequally distributed; such, for instance, as the difference of the Rhine below Cologne and above Strasburg. The greatest fall is commonly experienced at their commencement, though there are some striking exceptions to this. The whole descent of the Shannon, from its source in Loch Allen to the sea, a distance of 234 miles, is 146 feet, which is seven inches and a fraction in a mile, but it falls 97 feet in a distance of 15 miles, between Killaloe and Limerick, and occupies the remaining 219 miles in descending 49 feet. When water has once received an impulse by following a descent, the simple pressure of the particles upon each other is sufficient to keep it in motion long after its bed has lost all inclination. The chief effect of the absence of a declivity is a slower movement of the stream, and a more winding course, owing to the aqueous particles being more susceptible of divergence from their original direction by impediments in their path. Hence the tortuous character of the water-courses, chiefly arising from the streams meeting with levels after descending inclined planes, which so slackens their speed that they are easily diverted from a right-onward direction by natural obstacles, to which the force of their current is inferior. The Mæander was famed in classical antiquity for its mazy course, descending from the pastures of Phrygia, with many involutions, into the vine-clad province of the Carians, which it divided from Lydia near a plain properly called the Mæandrian, where the bed was winding in a remarkable degree. From the name of this river we have our word meandering, as applied to erratic streams.

The Rhine at Oberweisel.

This circumstance increases prodigiously the extent of their channels, and renders their navigation tedious, but the absence of that velocity of the current which would make it difficult is a compensation, while a larger portion of the earth enjoys the benefit of their waters. The sources of the Mississippi are only 1250 miles from its mouth, following a straight line, but 3200 miles, pursuing its real path; and the Forth is actually three times the length of a straight line drawn from its rise to its termination. The rivers which flow through flat alluvial plains frequently exhibit great sinuosities, their waters returning nearly to the same point after an extensive tour. The Moselle, after a curved course of seventeen miles, returns to within a few hundred yards of the same spot; and a steamer on the Mississippi, after a sail of twenty-five or thirty miles, is brought round again, almost within hail of the place where it was two or three hours before. In high floods, the waters frequently force a passage through the isthmuses which are thus formed, converting the peninsulas into islands, and forming a nearer route for the navigator to pursue. By the “grand cut off” on the Mississippi, vessels now pass from one point to another in half a mile, in order to accomplish which they had formerly a distance of twenty miles to traverse.

Rivers receive a peculiar impress from the geological character of the districts through which they flow. Those of primary or transition countries, where sudden declivities abound, are bold and rapid streams, with steep and high banks, and usually pure waters, owing to the surface not being readily abraded, generally emptying themselves by a single mouth which is deep and unobstructed. The streams of secondary and alluvial districts flow with slow but powerful current, between low and gradually descending banks, which, being composed of soft rocks or alluvial grounds, are easily worn away by the waters, and hence great changes are effected in their channels, and a peculiar color is given to their streams by the earthy particles with which they are charged. Many rivers have their names from this last circumstance. The Rio Negro, or Black River, which flows into the Amazon, is so called on account of the dark color of its waters, which are of an amber hue wherever it is shallow, and dark brown wherever the depth is great. The names of the two great streams which unite to form the Nile, the Bahr-el-Abiad, or White River, from the Mountains of the Moon, and the Bahr-el-Azrek, or Blue River, from Abyssinia, refer to the color which they receive from the quantity of earth with which they are impregnated. The united rivers, for some distance after their junction, preserve their colors distinct. This is the case likewise with the Rhine and the Moselle; the St. Lawrence and the Ottawa. The Upper Mississippi is a transparent stream, but assumes the color of the Missouri upon joining that river, the mud of which is as copious as the water can hold in suspension, and of a white soapy hue. The Ohio brings into it a flood of a greenish color. The bright and dark red waters of the Arkansas and Red River afterward diminish the whiteness derived from the Missouri, and the volume of the Lower Mississippi bears along a tribute of vegetable soil, collected from the most distant quarters, and of the most various kind—the marl of the Rocky and the clay of the Black Mountains—the earth of the Alleghanies—and the red-loam washed from the hills at the sources of the Arkansas and the Red River. Mr. Lyell states that water flowing at the rate of three inches per second will tear up fine clay; six inches per second, fine sand; twelve inches per second, fine gravel; and three feet per second, stones of the size of an egg. He remarks, likewise, that the rapidity at the bottom of a stream is everywhere less than in any part above it, and is greatest at the surface; and that in the middle of the stream the particles at the top move swifter than those at the sides. The ease with which running water bears along large quantities of sand, gravel, and pebbles, ceases to surprise when we consider that the specific gravity of rocks in water is much less than in air.

It is chiefly in primary and transition countries that the rivers exhibit those sudden descents, which pass under the general denomination of falls, and form either cataracts or rapids. They occur in secondary regions, but more rarely, and the descent is of a more gentle description. The falls are generally found in the passage of streams from the primitive to the other formations. Thus the line which divides the primitive and alluvial formations on the coast of the United States, is marked by the falls or rapids of its rivers, while none occur in the alluvial below. Cataracts are formed by the descent of a river over a precipice which is perpendicular, or nearly so, and depend, for their sublimity, upon the height of the fall, and the magnitude of the stream. Rapids are produced by the occurrence of a steeply-inclined plane, over which the flood rushes with great impetuosity, yet without being projected over a precipice. The great rivers of England—the Thames, Trent and Severn—exhibit no example of either cataract or rapid, but pursue a generally even and noiseless course; though near their sources, while yet mere brooks and rivulets, most of our home streams present these features in a very miniature manner. A true rapid occurs in the course of the Shannon, just above Limerick, where the river, forty feet deep, and three hundred yards wide, pours its body of water through and above a congregation of huge rocks and stones, extending nearly half a mile, and becomes quite unnavigable. Inglis had never heard of this rapid before arriving in its neighborhood; but ranks it in grandeur and effect, above either the Welsh water-falls or the Geisbach in Switzerland. The river Adige, in the Tyrol, near Meran, rushes, with resistless force and deafening noise, down a descent nearly a mile in length, between quiet, green, pastoral banks, presenting one of the most magnificent spectacles to be met with in Europe. The celebrated cataracts of the Nile are, more properly speaking, rapids, as there is no considerable perpendicular fall of the river; but for a hundred miles at Wady Hafel, the second cataract reckoning upward, there is a succession of steep descents, and a multitude of rocky islands, among which the river dashes amid clouds of foam, and is tossed in perpetual eddies. It is along the course of the American rivers, however, that the most sublime and imposing rapids are found, rendered so by the great volumes of water contained in their channels. The more remarkable are those of the St. Lawrence, the chief of which, called the Coteau de Luc, the Cedars, the Split Rock, and the Cascades, occur in succession for about nine miles above Montreal and the junction of the Ottawa. At the rapid of St. Anne, on the latter river, the more devout of the Canadian voyageurs are accustomed to land, and implore the protection of the patron saint on their perilous expeditions, before a large cross at the village that bears her name. The words of a popular song have familiarized English ears with this habit of the hardy boatmen:—

“Faintly as tolls the evening chime,

Our voices keep tune and our oars keep time.

Soon as the woods on shore look dim,

We’ll sing at St. Ann’s our parting hymn.

Row, brothers, row, the stream runs fast,

The Rapids are near, and the daylight’s past.

“Utawa’s tide! this trembling moon

Shall see us float over thy surges soon.

Saint of this green isle hear our prayers,

Oh, grant us cool heavens and favoring airs.

Blow, breezes, blow, the stream runs fast,

The Rapids are near, and the daylight’s past.”

Kaaterskill Falls.

The Kaaterskill Falls here represented are celebrated in America for their picturesque beauty. The waters which supply these cascades flow from two small lakes in the Catskill Mountains, on the west bank of the Hudson. The upper cascade falls one hundred and seventy-five feet, and a few rods below the second pours its waters over a precipice eighty feet high, passing into a picturesque ravine, the banks of which rise abruptly on each side to the height of a thousand to fifteen hundred feet.

In the grandeur of their cataracts, also, the American rivers far surpass those of other countries, though several falls on the ancient continent have a greater perpendicular height, and are magnificent objects. In Sweden, the Gotha falls about 130 feet at Trolhetta, the greatest fall in Europe of the same body of water. The river is the only outlet of a lake, a hundred miles in length and fifty in breadth, which receives no fewer than twenty-four rivers; the water glides smoothly on, increasing in rapidity, but quite unruffled, until it reaches the verge of the precipice; it then darts over it in one broad sheet, which is broken by some jutting rocks, after a descent of about forty feet. Here begins a spectacle of great grandeur. The moving mass is tossed from rock to rock, now heaving itself up in yellow foam, now boiling and tossing in huge eddies, growing whiter and whiter in its descent, till completely fretted into one beautiful sea of snowy froth, the spray, rising in dense clouds, hides the abyss into which the torrent dashes; but when momentarily cleared away by the wind, a dreadful gulf is revealed, which the eye cannot fathom. Upon the arrival of a visitor at Trolhetta, a log of wood is sent down the fall, by persons who expect a trifle for the exhibition. It displays the resistless power of the element. The log, which is of gigantic dimensions, is tossed like a feather upon the surface of the water, and is borne to the foot almost in an instant. In Scotland, the falls of its rivers are seldom of great size; but the rocky beds over which they roar and dash in foam and spray—the dark, precipitous glens into which they rush—and the frequent wildness of the whole scenery around, are compensating features. The most remarkable instances are the Upper and Lower Falls of Foyers, near Loch Ness. At the upper fall, the river precipitates itself, at three leaps, down as many precipices, whose united depth is about 200 feet; but, at the lower, it makes a descent at once of 212 feet, and, after heavy rains, exhibits a grand appearance. The fall of the Rhine at Schaffhausen is only 70 feet; but the great mass of its waters, 450 feet in breadth, gives it an imposing character. The Teverone, near Tivoli, a comparatively small stream, is precipitated nearly 100 feet; and the Velino, near Terni, falls 300, which is generally considered the finest of the European cataracts. This “hell of waters,” as Byron calls it, is of artificial construction. A channel was dug by the Consul Carius Dentatus in the year 274 B. C., to convey the waters to the precipice, but having become filled up by a deposition of calcareous matter, it was widened and deepened by order of Pope Paul IV. “I saw,” says Byron, “the Cascata del Marmore of Terni twice at different periods; once from the summit of the precipice, and again from the valley below. The lower view is far to be preferred, if the traveler has time for one only; but in any point of view, either from above or below, it is worth all the cascades and torrents of Switzerland put together.”

Falls of Trolhetta.

In the Alpine highlands, the Evanson descends upward of 1200 feet, and the Orco forms a vertical cataract of 2400; but in these instances the quantity of water is small, and the chief interest is produced by the height from which it falls. At Staubbach, in the Swiss Canton of Berne, a small stream descends 1400 feet, and is shattered almost entirely into spray before it reaches the bottom.

Falls of Terni.

Waterfalls appear upon their grandest scale in the American continent. They are not remarkable for the height of the precipices over which they descend, or for the picturesque forms of the rocky cliffs amid which they are precipitated, like the Alpine cataracts; but while these are usually the fall of streamlets merely, those of the western world are the rush of mighty rivers. The majority are in the northern part of the continent, but the greatest vertical descent of a considerable body of water is in the southern, at the Falls of Tequendama, where the river of Funza disembogues from the elevated plain or valley of Santa Fe de Bogota. This valley is at a greater height above the level of the sea than the summit of the great St. Bernard, and is surrounded by lofty mountains. It appears to have been formerly the bed of an extensive lake, whose waters were drained off when the narrow passage was forced through which the Funza river now descends from the elevated inclosed valley toward the bed of the Rio Magdalena. Respecting this physical occurrence Gonzalo Ximenes de Quesada, the conqueror of the country, found the following tradition disseminated among the people, which probably contains a stratum of truth invested with a fabulous legend. In remote times the inhabitants of Bogota were barbarians, living without religion, laws, or arts. An old man on a certain occasion suddenly appeared among them of a race unlike that of the natives, and having a long, bushy beard. He instructed them in the arts, but he brought with him a malignant, although beautiful woman, who thwarted all his benevolent enterprises. By her magical power she swelled the current of the Funza, and inundated the valley, so that most of the inhabitants perished, a few only having found refuge in the neighboring mountains. The aged visitor then drove his consort from the earth, and she became the moon. He next broke the rocks that inclosed the valley on the Tequendama side, and by this means drained off the waters. Then he introduced the worship of the sun, appointed two chiefs, and finally withdrew to a valley, where he lived in the exercise of the most austere penitence during 2000 years. The Tequendama cataract is remarkably picturesque. The river a little above it is 144 feet in breadth, but at the crevice it is much narrower. The height of the fall is 574 feet, and the column of vapor that rises from it is visible from Santa Fe at the distance of 17 miles. At the foot of the precipice the vegetation has a totally different appearance from that at the summit, and the traveler, following the course of the river, passes from a plain in which the cereal plants of Europe are cultivated, and which abounds with oaks, elms, and other trees resembling those of the temperate regions of the northern hemisphere, and enters a country covered with palms, bananas, and sugar-canes.

In Northern America, however, we find the greatest of all cataracts, that of the Niagara, the sublimest object on earth, according to the general opinion of all travelers. More varied magnificence is displayed by the ocean, and giant masses of the Andes and Himalaya; but no single spectacle is so striking and wonderful as the descent of this sea-like flood, the overplus of four extensive lakes. The river is about thirty-three miles in length, extending from lake Erie to lake Ontario, and three-quarters of a mile wide at the fall. There is nothing in the neighboring country to indicate the vicinity of the astonishing phenomenon here exhibited. Leaving out lake Erie, the traveler passes over a level though somewhat elevated plain, through which the river flows tranquilly, bordered by fertile and beautiful banks; but soon a deep, awful sound, gradually growing louder, breaks upon the ear—the roar of the distant cataract. Yet the eye discerns no sign of the spectacle about to be disclosed until a mile from it, when the water begins to ripple, and is broken into a series of dashing and foaming rapids. After passing these, the river becomes more tranquil, though rolling onward with tremendous force, till it reaches the brink of the great precipice. The fall itself is divided into two unequal portions by the intervention of Goat Island, a façade near 1000 feet in breadth. The one on the British side of the river, called the Horse-Shoe fall, from its shape, according to the most careful estimate, is 2100 feet broad, and 149 feet 9 inches high. The other or American fall is 1140 feet broad, and 164 feet high. The former is far superior to the latter in grandeur. The great body of the water passes over the precipice with such force, that it forms a curved sheet which strikes the stream below at the distance of 50 feet from the base, and some travelers have ventured between the descending flood and the rock itself. Hannequin asserts that four coaches might be driven abreast through this awful chasm. The quantity of water rolling over these falls has been estimated at 670,250 tons per minute. It is impossible to appreciate the scene created by this immense torrent, apart from its site.

“The thoughts are strange that crowd into my brain,

While I look upward to thee. It would seem

As if God poured thee from his hollow hand,

And hung his bow upon thine awful front;

And spoke in that loud voice which seemed to him

Who dwelt in Patmos for his Saviour’s sake,

The sound of many waters; and had bade

Thy flood to chronicle the ages back,

And notch his centuries in the eternal rocks.

Deep calleth unto deep. And what are we,

That hear the question of that voice sublime?

Oh! what are all the notes that ever rung

From war’s vain trumpet, by thy thundering side?

Yea, what is all the riot man can make,

In his short life, to thy unceasing roar?

And yet, Bold Babbler! what art thou to Him,

Who drowned a world, and heaped the waters far

Above its loftiest mountains?—a light wave,

That breaks, and whispers of its Maker’s might.”

It has been remarked that at Niagara, several objects composing the chief beauty of other celebrated water-falls are altogether wanting. There are no cliffs reaching to an extraordinary height, crowned with trees, or broken into picturesque and varied forms; for, though one of the banks is wooded, the forest scenery on the whole is not imposing. The accompaniments, in short, rank here as nothing. There is merely the display, on a scale elsewhere unrivaled, of the phenomena appropriate to this class of objects. There is the spectacle of a falling sea, the eye filled almost to its utmost reach by the rushing of mighty waters. There is the awful plunge into the abyss beneath, and the reverberation thence in endless lines of foam, and in numberless whirlpools and eddies; there are clouds of spray that fill the whole atmosphere, amid which the most brilliant rainbows, in rapid succession, glitter and disappear; above all, there is the stupendous sound, of the peculiar character of which all writers, with their utmost efforts, seem to have vainly attempted to convey an idea. Bouchette describes it as “grand, commanding and majestic, filling the vault of heaven when heard in its fullness”—as “a deep, round roar, and alternation of muffled and open sounds, to which there is nothing exactly corresponding.” Captain Hall compares it to the ceaseless, rumbling, deep-monotonous sound of a vast mill, which, though not very practical, is generally considered as approaching near to the reality. Dr. Reed states, “it is not like the sea; nor like the thunder; nor like any thing I have heard. There is no roar, no rattle; nothing sharp or angry in its tones; it is deep, awful—One.” The diffusion of the noise varies according to the state of the atmosphere and the direction of the wind, but it may be heard under favorable circumstances through a distance of forty-six miles: at Toronto, across Lake Ontario. To the geologist the Niagara falls have interest, on account of the movement which it is supposed has taken place in their position. The force of the waters appears to be wearing away the rock over which they rush, and gradually shifting the cataract higher up the river. It is conceived that by this process it has already receded in the course of ages through a distance of more than seven miles, from a point between Queenstown and Lewiston, to which the high level of the country continues. The rate of procession is fixed, according to an estimate, mentioned by Mr. M’Gregor, at eighteen feet during the thirty years previous to 1810; but he adds another more recent, which raises it to one hundred and fifty feet in fifty years.

The following account of a visit to the Falls of Niagara has been communicated to us by Mr. N. Gould. It forms a part of his unpublished Notes on America and Canada.

“My attention had been kept alive, and I was all awake to the sound of the cataract; but, though within a few miles, I heard nothing. A cloud hanging nearly steady over the forest, was pointed out to me as the ‘spray cloud;’ at length we drove up to Forsyth’s hotel, and the mighty Niagara was full in view. My first impression was that of disappointment—a sour sort of deep disappointment, causing, for a few minutes, a kind of vacuity; but, while I mused, I began to take in the grandeur of the scene. This impression is not unusual on viewing objects beyond the ready catch of the senses; Stonehenge and St. Paul’s cathedral seldom excite much surprise at first sight; the enormous Pyramids, I have heard travelers say, strike with awe and silence on the near approach, but require time to appreciate. The fact is, that the first view of Niagara is a bad one; and the eye, in this situation, can comprehend but a small part of the wonderful scene. You look down upon the cataract instead of up to it; the confined channel, and the depth of it, prevent the astounding roar which was anticipated; and, at the same time, the eye wanders midway between the water and the cloud formed by the spray, which it sees not. After a quarter of an hour’s gaze, I felt a kind of fascination—a desire to find myself gliding into eternity in the centre of the Grand Fall, over which the bright green water appears to glide, like oil, without the least commotion. I approached nearly to the edge of the ‘Table Rock,’ and looked into the abyss. A lady from Devonshire had just retired from the spot; I was informed she had approached its very edge, and sat with her feet over the edge—an awful and dangerous proceeding. Having viewed the spot, and made myself acquainted with some of its localities, I returned to the hotel (Forsyth’s) which, as well as its neighboring rival, is admirably situated for the view; from my chamber-window I looked directly upon it, and the first night I could find but little sleep from the noise. Every view I took increased my admiration; and I began to think that the other Falls I had seen were, in comparison, like runs from kettle-spouts on hot plates. I remained in this interesting neighborhood five days, and saw the Fall in almost every point of view. From its extent, and the angular line it forms, the eye cannot embrace it all at once; and, probably, from this cause it is that no drawing has ever yet done justice to it. The grandest view, in my opinion, is at the bottom, and close to it, on the British side, where it is awful to look up through the spray at the immense body as it comes pouring over, deafening you with its roar; the lighter spray, at a considerable distance, hangs poised in the air like an eternal cloud. The next best view is on the American side, to reach which you cross in a crazy ferry-boat: the passage is safe enough, but the current is strongly agitated. Its depth, as near to the falls as can be approached, is from 180 to 200 feet. The water, as it passes over the rock, where it is not whipped into foam, is a most beautiful sea-green, and it is the same at the bottom of the Falls. The foam, which floats away in large bodies, feels and looks like salt water after a storm: it has a strong fishy smell. The river, at the ferry, is 1170 feet wide. There is a great quantity of fish, particularly sturgeon and bass, as well as eels; the latter creep up against the rock under the Falls, as if desirous of finding some mode of surmounting the heights. Some of the visitors go under the Falls, an undertaking more curious than pleasant. Three times did I go down to the house, and once paid for my guide and bathing dress, when something occurred to prevent me. The lady before alluded to performed the ceremony, and it is recorded, with her name, in the book, that she went to the farthest extent that the guides can or will proceed. It is described as like being under a heavy shower-bath, with a tremendous whirlwind driving your breath from you, and causing a peculiarly unpleasant sensation at the chest; the footing over the débris being slippery, the darkness barely visible, and the roar almost deafening. In the passage you kick against eels, many of them unwilling to move, even when touched: they appear to be endeavoring to work their way up the stream.”

Supposing the cataract to be receding at the rate of fifty yards in forty years, as it is stated by Captain Hall, the ravine which extends from thence to Queenstown, a distance of seven miles, will have required nearly ten thousand years for its excavation; and, at the same rate, it will require upward of thirty-five thousand years for the falls to recede to Lake Erie, a distance of twenty-five miles. The draining of the lake, which is not more than ten or twelve fathoms in average depth, must then take place, causing a tremendous deluge by the sudden escape of its waters. In addition to the gradual erosion of the limestone, which forms the bed of the Niagara at and above the falls, huge masses of the rock are occasionally detached by the undermining of the soft shale upon which it rests. This effect is produced by the action of the spray powerfully thrown back upon the stratum of shale; and hence has arisen the great hollow between the descending flood and the precipice. An immense fragment fell on the 28th of December, 1828, with a crash that shook the glass vessels in the adjoining inn, and was felt at the distance of two miles from the spot. By this disintegration, the angular or horse-shoe form of the great fall was lessened, and its grandeur heightened by the line of the torrent becoming more horizontal. A similar dislocation had occurred in the year 1818; and the aspect of the precipice always so threatening, owing to the wearing away of the lower stratum, as to render it an affair of some real hazard to venture between the falling waters and the rock. Miss Martineau undertook the enterprise, clad in the oil-skin costume used for the expedition, and thus remarks concerning it:—“A hurricane blows up from the cauldron; a deluge drives at you from all parts; and the noise of both wind and waters, reverberated from the cavern, is inconceivable. Our path was sometimes a wet ledge of rock, just broad enough to allow one person at a time to creep along: in other places we walked over heaps of fragments, both slippery and unstable. If all had been dry and quiet, I might probably have thought this path above the boiling basin dangerous, and have trembled to pass it; but, amidst the hubbub of gusts and floods, it appeared so firm a footing, that I had no fear of slipping into the cauldron. From the moment that I perceived we were actually behind the cataract, and not in a mere cloud of spray, the enjoyment was intense. I not only saw the watery curtain before me like tempest-driven snow, but, by momentary glances, could see the crystal roof of this most wonderful of Nature’s palaces. The precise point where the flood quitted the rock was marked by a gush of silvery light, which of course was brighter where the waters were shooting forward, than below, where they fell perpendicularly.” There have been several hair-breadth escapes, and not a few fatal accidents, at Niagara, the relation of which is highly illustrative of Indian magnanimity. Tradition preserves the memory of the warrior of the red race, who got entangled in the rapids above the falls, and, seeing his fate inevitable, calmly resigned himself to it, and sat singing in his canoe till buried by the torrent in the abyss to which it plunges. The celebrated Chateaubriand narrowly escaped a similar fate. On his arrival he had repaired to the fall, having the bridle of his horse twisted round his arm. While he was stopping to look down, a rattle-snake stirred among the neighboring bushes. The horse was startled, reared, and ran back toward the abyss. He could not disengage his arm from the bridle; and the horse, more and more frightened, dragged him after him. His fore-legs were all but off the ground; and, squatting on the brink of the precipice, he was upheld merely by the bridle. He gave himself up for lost; when the animal, astonished at this new danger, threw itself forward with a pirouette, and sprang to the distance of ten feet from the edge of the abyss.

The erosive action of running water, which is urging the Niagara Falls toward Lake Erie, is strikingly exhibited by several rivers which penetrate through rocks and beds of compact strata, and have either scooped out their own passage entirely, or widened and deepened original tracks and fissures in the surface, into enormous wall-sided valleys. The current of the Simeto—the largest Sicilian river round the base of Etna—was crossed by a great stream of lava about two centuries and a half ago; but, since that era, the river has completely triumphed over the barrier of homogeneous hard blue rock that intruded into its channel, and cut a passage through it from fifty to a hundred feet broad, and from forty to fifty deep. The formation of the magnificent rock-bridge which overhangs the course of the Cedar creek, one of the natural wonders of Virginia, is very probably due in part to the solvent and abrading power of the stream. This sublime curiosity is 213 feet above the river, 60 feet wide, 90 long, and the thickness of the mass at the summit of the arch is about 40 feet. The bridge has a coating of earth, which gives growth to several large trees. To look down from its edge into the chasm inspires a feeling answering to the words of Shakspeare:

“Come on, sir; here’s the place:—stand still. How fearful

And dizzy ’tis, to cast one’s eyes so low!”

Few have resolution enough to walk to the parapet, in order to peep over it. But if the view from the top is painful and intolerable, that from below is pleasing in an equal degree. The beauty, elevation, and lightness of the arch, springing as it were up to heaven, present a striking instance of the graceful in combination with the sublime. This great arch of rock gives the name of Rock-bridge to the county in which it is situated, and affords a public and commodious passage over a valley which cannot be crossed elsewhere for a considerable distance. Under the arch, thirty feet from the water, the lower part of the letters G. W. may be seen, carved in the rock. They are the initials of Washington, who, when a youth, climbed up hither, and left this record of his adventure. We have several examples of the disappearance of rivers, and their emergence after pursuing for some distance a subterranean course. In these cases a barrier of solid rock, overlaying a softer stratum has occurred in their path; and the latter has been gradually worn away by the waters, and a passage been constructed through it. Thus the Tigris, about twenty miles from its source, meets with a mountainous ridge at Diglou, and, running under it, flows out at the opposite side. The Rhone, also, soon after coming within the French frontier, passes under ground for about a quarter of a mile. Milton, in one of his juvenile poems, speaks of the

“Sullen Mole, that runneth underneath;”

and Pope calls it, after him, the

“Sullen Mole, that hides his diving flood.”

Natural Bridge, Virginia.

The Hamps and the Manifold, likewise—two small streams in Derbyshire—flow in separate subterraneous channels for several miles, and emerge within fifteen yards of each other in the grounds of Ilam Hall. That these are really the streams which are swallowed up at points several miles distant has been frequently proved, by watching the exit of various light bodies that have been absorbed at the swallows. At their emergence, the waters of the two rivers differ in temperature about two degrees—an obvious proof that they do not anywhere intermingle. On the side of the hill, which is overshadowed with spreading trees, just above the spot where the streams break forth into daylight, there is a rude grotto, scooped out of the rock, in which Congreve is said to have written his comedy of the “Old Bachelor,” and a part of his “Mourning Bride.” In Spain, a similar phenomenon is exhibited by the Guadiana; but it occurs under different circumstances. It disappears for about seven leagues—an effect of the absorbing power of the soil—the intervening space consisting of sandy and marshy grounds, across which the road to Andalusia passes by a long bridge or causeway. The river reappears with greater power, after its dispersion, at the Ojos de Guadiana—the Eyes of the stream.

[To be continued.

———

BY J. HUNT, JR.

———

Not those who’ve trod the martial field,

And led to arms a battling host,

And at whose name “the world grew pale,”

Will be in time remembered most:

But they who’ve walked the “paths of peace,”

And gave their aid to deeds t’were just,

Shall live for aye, on Mem’ry’s page,

When heroes sleep in unknown dust.

———

BY HENRY WILLIAM HERBERT, AUTHOR OF “FRANK FORESTER’S FIELD SPORTS,” “FISH AND FISHING,” ETC.

———

THE BITTERN. AMERICAN BITTERN. Ardea Minor sive Lentiginos.

THE INDIAN HEN. THE QUAWK. THE DUNKADOO.

This, though a very common and extremely beautiful bird, with an exceedingly extensive geographic range, is the object of a very general and perfectly inexplicable prejudice and dislike, common, it would seem, to all classes. The gunner never spares it, although it is perfectly inoffensive; and although the absurd prejudice, to which I have alluded, causes him to cast it aside, when killed, as uneatable carrion; its flesh being in reality very delicate and juicy, and still held in high repute in Europe; while here one is regarded very much in the light of a cannibal, as I have myself experienced, for venturing to eat it. The farmer and the boatman stigmatize it by a filthy and indecent name. The cook turns up her nose at it, and throws it to the cat; for the dog, wiser than his master, declines it—not as unfit to eat, but as game, and therefore meat for his masters.

Now the Bittern would not probably be much aggrieved at being voted carrion, provided his imputed carrion-dom, as Willis would probably designate the condition, procured him immunity from the gun.

But to be shot first and thrown away afterward, would seem to be the very excess of that condition described by the common phrase of adding injury to insult.

Under this state of mingled persecution and degradation, it must be the Bittern’s best consolation that, in the days of old, when the wine of Auxerre, now the common drink of republican Yankeedom, which annually consumes of it, or in lieu of it, more than grows of it annually in all France, was voted by common consent the drink of kings—he, with his congener and compatriot the Heronschaw, was carved by knightly hands, upon the noble deas under the royal canopy, for gentle dames and peerless damoiselles; nay, was held in such repute, that it was the wont of prowest chevaliers, when devoting themselves to feats of emprise most perilous, to swear “before God, the bittern, and the ladies!” an honor to which no quadruped, and but two plumy bipeds, other than himself, the heron and the peacock, were admitted.

Those were the days, before gunpowder, “grave of chivalry,” was taught to Doctor Faustus by the Devil, who did himself no good by the indoctrination, but exactly the reverse, since war is thereby rendered less bloody, and much more uncruel—the days when no booming duck-gun keeled him over with certain and inglorious death, as he flapped up with his broad vans beating the cool autumnal air, and his long, greenish-yellow legs pendulous behind him, from out of the dark sheltering water-flags by the side of the brimful river, or the dark woodland tarn; but when the cheery yelp of a cry of feathery-legged spaniels aroused him from his arundinaceous, which is interpreted by moderns reedy, lair; when the triumphant whoop of the jovial falconers saluted his uprising; and when he was done to death right chivalrously, with honorable law permitted to him, as to the royal stag, before the long-winged Norway falcons, noblest of all the fowls of air, were unhooded and cast off to give him gallant chase.

If, when struck down from his pride of place by the crook-beaked blood-hound of the air, his legs were mercilessly broken, and his long bill thrust into the ground, that the falcon might dispatch him without fear of consequences, and at leisure, it was doubtless a source of pride to him, as to the tortured Indian at the stake, to be so tormented, since the amount of the torture was commensurate with the renown of the tortured; besides—for which the Bittern was, of course, truly grateful—it was his high and extraordinary prerogative to have his legs broken as aforesaid, and his long bill thrust into the ground, by the fair hand of the loveliest lady present—thrice blessed Bittern of the days of old.

A very different fate, in sooth, from being riddled with a charge of double Bs from a rusty flint-lock Queen Anne’s musket, poised by the horny paws of John Verity, and then ignobly cast to fester in the sun, among the up-piled eel-skins, fish-heads, king-crabs, and the like, with which, in lieu of garden-patch or well-trained rose-bush, the south-side Long Islander ornaments his front-door yard, rejoicing in the effluvia of the said decomposed piscine exuviæ, which he regards as “considerable hullsome,” beyond Sabæan odors, Syrian nard, or frankincense from Araby the blest!

Being eaten is being eaten after all; whether it be by a New Zealand war-chief, a New York alderman, a peerless lady, or a muck-worm; and I suppose it feels much the same, after one is once well dead; but, if I had my choice, I would most prefer to be eaten by the damoiselle of high degree, and most dislike to be battened on by the alderman, as being more ravenous and less appreciative than either Zealander or muck-worm.

The Bittern, however, be it said in sober earnest, although like many other delicious dishes prized by the wiser ancients, but now fallen into disuse, if not into disrepute—to wit, the heronschaw, the peacock, the curlew, and the swan—all first-rate dainties to the wise—is a viand not easily to be beaten, especially if he be sagely cooked in a well-baked, rich-crusted pastry, with a tender and fat rump-steak in the bottom of the dish, a beef’s kidney scored to make gravy, a handful of cloves, salt and black pepper quantum suff., a dozen hard-boiled eggs, and a pint of scalding-hot port wine poured in just before you serve up.

What you say, is perfectly true, my dear madam, cooked in that manner an old India rubber shoe is good; not only would be, but is. But you’d better believe it, a Bittern is a great deal better. If you don’t believe me, try the Bittern, and then if you prefer it, adhere to the shoe.

But now to quit his edible qualifications and turn to his personal appearance, habits of life, and location, and other characteristics, we will say of him, in the words of Wilson, that eloquent pioneer in the natural history of America, that the American Bittern, whom it pleases the Count de Buffon to designate as Le Butor de la Baye de Hudson, “is another nocturnal species, common to all our sea and river marshes, though nowhere numerous. It rests all day among the reeds and rushes, and, unless disturbed, flies and feeds only during the night. In some places it is called the Indian Hen; on the sea-coast of New Jersey it is known by the name of dunkadoo, a word probably imitative of its common note. They are also found in the interior, having myself killed one at the inlet of the Seneca Lake, in October. It utters at times, a hollow, guttural note among the reeds, but has nothing of that loud, booming sound for which the European Bittern is so remarkable. This circumstance, with its great inferiority of size, and difference of marking, sufficiently prove them to be two distinct species, although, hitherto, the present has been classed as a mere variety of the European Bittern. These birds, we are informed, visit Severn river, at Hudson’s Bay, about the beginning of June; make their nests in swamps, laying four cinereous green eggs among the long grass. The young are said to be, at first, black.

“These birds, when disturbed, rise with a hollow kwa, and are then easily shot down, as they fly heavily. Like other night birds, their sight is most acute during the evening twilight; but their hearing is, at all times, exquisite.

“The American Bittern is twenty-seven inches long, and three feet four inches in extent; from the point of the bill to the extremity of the toes, it measures three feet; the bill is four inches long; the upper mandible black; the lower, greenish yellow; lores and eyelids, yellow; irides, bright yellow; upper part of the head, flat, and remarkably depressed; the plumage there is of a deep blackish brown, long behind and on the neck, the general color of which is a yellowish brown, shaded with darker; this long plumage of the neck the bird can throw forward at will, when irritated, so as to give him a more formidable appearance; throat, whitish, streaked with deep brown; from the posterior and lower part of the auriculars, a broad patch of deep black passes diagonally across the neck, a distinguished characteristic of this species; the back is deep brown, barred, and mottled with innumerable specks and streaks of brownish yellow; quills, black, with a leaden gloss, and tipped with yellowish brown; legs and feet, yellow, tinged with pale green; middle claw, pectinated; belly, light yellowish brown, streaked with darker; vent, plain; thighs, sprinkled on the outside with grains of dark brown; male and female, nearly alike, the latter somewhat less. According to Bewick, the tail of the European Bittern contains only ten feathers; the American species has, invariably, twelve. The intestines measured five feet six inches in length, and were very little thicker than a common knitting-needle; the stomach is usually filled with fish or frogs.[1]

“This bird, when fat, is considered by many to be excellent eating.”

It is on the strength of Mr. Wilson’s statement as above that I have given among the vulgar appellations of this beautiful bird that of Dunkadoo; though I must admit that I never heard him called a Dunkadoo, either on the sea-coast of New Jersey or any where else; and further must put it on record, that if the sea-coasters of New Jersey did coin the said melodious word as imitative of its common note, they proved much worse imitators than I have found them in whistling bay snipe, hawnking Canada geese, or yelping Brant. They might just as well have called him a Cockatoo, while they were about it.

The other name, Quawk, by which it is generally known both on the sea-coast of New Jersey, and every where else where the vernacular of America prevails, is precisely imitative of the harsh clanging cry with which he rises from the reeds in which he lurks during the day-time, and which he utters while disporting himself in queer clumsy gyrations in mid air, over the twilight marshes in the dusk of summer evenings; and how nearly Quawk approaches to Dunkadoo, that one of my readers who is the least appreciative of the comparative value of sweet sounds, can judge as well as I can.

In England the Bittern, who there is possessed of a voice between the sounds of a bassoon and kettle-drum, with which he makes a most extraordinary booming noise, which can be heard for miles, if not for leagues, over the midnight marshes, a noise the most melancholy and unearthly that ever shot superstitious horror into the bosom of the belated wayfarer, who is unconscious of its cause, has also been designated by the country people, from his cry, “the bog-bumper,” and the “bluttery bump”—but as our bird—the United Stateser, I mean, or Alleghanian, as the New York Historical Society Associates would designate their countrymen—Bittern never either booms, blutters or bumps, but only quawks; a quawk only he must be content to remain, whether with the sea-coasters of New Jersey, the south-siders of Long Island, or my friends, the Ojibwas of Lake Huron.

In another respect I cannot precisely agree with the acute and observant naturalist quoted above, as to its ungregarious nature, since on more occasions than one I have seen these birds together in such numbers, and under such circumstances of association, as would certainly justify the application to them of the word flock.

One of these occasions I remember well, as it occurred while snipe-shooting on the fine marshes about the riviere aux Canards in Canada West, when several times I saw as many as five or six flush together from out of the high reeds, as if in coveys; and this was late in September, so that they could not well have been young broods still under the parental care.

At another time I saw them in yet greater numbers and acting together, as it appeared, in a sort of concert. I was walking, I cannot now recollect why, or to what end, along the marshes on the bank of the Hackensack river, between the railroad bridge and that very singular knoll named Snakehill, which rises abruptly out of the meadows like an island out of the ocean. It was late in the summer evening, the sun had gone quite down, and a thick gray mist covered the broad and gloomy river. On a sudden, I was almost startled by a loud quawk close above my head; and, on looking up, observed a large Bittern wheeling round and round, now soaring up a hundred feet or more, and then suddenly diving, or to speak more accurately, falling, plump down, with his legs and wings all relaxed and abroad, precisely as if he had been shot dead, uttering at the moment of each dive a loud quawk. While I was still engaged in watching his manœuvres, he was answered, and a second Bittern came floating through the darksome air, and joined his companion. Another and another followed, and within ten or twelve minutes, there must have been from fifteen to twenty of these large birds all gamboling and disporting themselves together, circling round one another in their gyratory flight, and making the night any thing, certainly, but melodious by their clamors. What was the meaning of those strange nocturnal movements I cannot so much as guess; it was not early enough in the spring to be connected in any way with the amatory propensities of the birds, or I should have certainly set it down, like the peculiar flight, the unusual chatter, and the drumming, performed with the quill-feathers, of the American snipe—Scolopax Wilsonii—commonly known as the English snipe, during the breeding season, as a preliminary to incubation, nidification, and the reproduction of the species—in a word, as a sort of bird courtship. The season of the year put a stopper on that interpretation, and I can conceive none other than that the Quawks were indulging themselves in an innocent game of romps, preparatory to the more serious and solemn enjoyment of a fish and frog supper.

The Bittern, it appears, on the Severn river, emptying into Hudson’s Bay, makes its nest in the long grass of the marshes, and there lays its eggs and rears its black, downy young; but several years ago, while residing at Bangor, in Maine, while on a visit to a neighboring heronry, situated on an island covered with a dense forest of tall pines and hemlocks, I observed a pair of Bitterns flying to and fro, from the tree-tops to the river and back, with fish in their bills, among the herons which were similarly engaged in the same interesting occupation of feeding their young. One of these, the male bird, I shot, for the purpose of settling the fact, and we afterward harried the nest, and obtained two full-grown young birds, almost ready to fly.

Hence, I presume, that, like many other varieties of birds, the Bittern adapts his habits, even of nidification, to the purposes of the case, and that where no trees are to be found, in which he can breed, he makes the best he can of it, and builds on the ground; but it is my opinion that his more usual and preferred situation for his nest is in high trees, as is the case with his congeners, the Green Bittern, the blue heron, the beautiful white egret, the night heron, which may be all found breeding together in hundreds among the red cedars on the sea beach of Cape May. The nest, which I found in Maine, was built of sticks, precisely similar to that of the herons.

The Bittern is a more nocturnal bird than the heron, and is never seen, like him, standing motionless as a gray stone, with his long slender neck recurved, his javelin-like bill poised for the stroke, and his keen eye piercing the transparent water in search of the passing fry.

All day he rambles about among the tall grass and reeds of the marshes, sometimes pouncing on an unfortunate frog, a garter-snake, or a mouse, for, like the blue heron, he is a clever and indefatigable mouser; but when the evening comes, he bestirs himself, spreads his broad vans, rises in air, summoning up his comrades by his hoarse clang, and wings his way over the dim morasses, to the banks of some neighboring rivulet or pool, where he watches, erect sentinel, for the passing fish, shiners, small eels, or any of the lesser tribes of the cyprinidæ, and whom he detects, wo-betide; for the stroke of his sharp-pointed bill, dealt with Parthian velocity and certitude by the long arrowy neck, is sure death to the unfortunate.

Mr. Giraud, in his excellent book on the birds of Long Island, thus speaks of the American Bittern, and that so truthfully and agreeably withal, that I make no apology for quoting his words at length.

“This species is said to have been the favorite bird of the Indians, and at this day is known to many persons by the name of “Indian Hen,” or “Pullet,” though more familiarly by the appellation of “Look-up,” so called from its habit, when standing on the marshes, of elevating its head, which position, though probably adopted as a precautionary measure, frequently leads to its destruction. The gunners seem to have a strong prejudice against this unoffending bird, and whenever opportunity offers, seldom allow it to escape. It does not move about much by day, though it is not strictly nocturnal, but is sometimes seen flying low over the meadow, in pursuit of short-tailed or meadow-mice, which I have taken whole from its stomach. It also feeds on fish, frogs, lizards, etc.; and late in the season, its flesh is in high esteem—but it cannot be procured in any number except when the marshes are overflowed by unusually high tides, when it is hunted much after the manner the gunners adopt when in pursuit of rail. On ordinary occasions, it is difficult to flush; the instant it becomes aware that it has attracted the attention of the fowler, it lowers its head and runs quickly through the grass, and when again seen, is usually in a different direction from that taken by its pursuer, whose movements it closely watches; and when thus pursued, seldom exposes more than the head, leading the gunner over the marsh without giving him an opportunity to accomplish his purpose.

“When wounded, it makes a vigorous resistance, erects the feathers on the head and neck, extends its wings, opens its bill, and assumes a fierce expression—will attack the dog, and even its master, and when defending itself, directs its acute bill at its assailant’s eye. It does not usually associate with other herons, nor does it seem fond of the society of its own species. Singly or in pairs it is distributed over the marshes, but with us it is not abundant.”

The geographical range of this bird is, as I have before stated, very extensive, extending from the shores of Hudson’s Bay, in the extreme north, so far south at least as to the Cape of Florida, and probably yet farther down the coasts of the Mexican gulfs.

That fanciful blockhead, the Count de Buffon—for he was a most almighty blockhead when he set himself drawing on his imagination for facts—with his usual eloquent absurdity, describes the species as “exhibiting the picture of wretchedness, anxiety, and indigence; condemned to struggle perpetually with misery and want; sickened with the restless cravings of a famished appetite;” a description so ridiculously untrue, that were it possible for these birds to comprehend it, it would excite the risibility of the whole tribe.

If the count had seen the Quawks, as I did, at their high jinks, by the Hackensack, he would have scarce written such folly; and had he been a little more of a true philosopher, and thorough naturalist, he would have comprehended that whatsoever being the Universal Creator hath created unto any end—to that end he adapted him, not in his physical structure only, but in his instincts, his appetites, his tastes, his pleasures and his pains; and that to the patient Bittern, motionless on his mud-bank, that watch is as charming, as is the swift pursuit of the small bird to the falcon, of the rabbit to the fox, of the hare to the greyhound, of all the animals devoured to all the devourers; and that his frog diet is as dear to Ardea Lentiginosa, as his flower dew to the humming-bird, or his canvas-backs, in the tea-room, to an alderman of Manhattan.

As for the Bittern starving, eat a fat one in a pie, and you’ll be a better judge of that probability, than any Buffon ever bred in France; and as for all the rest—it is just French humbug.

At another opportunity, I may speak of others of this interesting tribe. Sportsmen rarely go out especially to hunt them, except in boats, as described by Mr. Giraud, but in snipe and duck-shooting in the marshes they are constantly flushed and shot.

Pointers and setters will both stand them steadily, and cocking spaniels chase them with ardor. Their flight is slow and heavy, and their tardy movements and large size render them an easy mark even to a novice. They are not a hardy bird, as to the bearing off shot; for the loose texture of their feathers is more than ordinarily penetrable, and a light charge of No. 8, will usually bring them down with certainty.

When wing-tipped they fight fiercely, striking with their long beaks at the eyes of the assailant, whether dog or man, and laying aside resistance only with their lives.

Early in the autumn is the best time both for shooting him and eating him, and for the latter purpose he is better than for the former; but for the noble art of falconry, the mystery of rivers, he is the best of all. Avium facile princeps; easily the Topsawyer of the birds of flight, unless it be his cousin german heronshaw, whom the princely Dane knew from a hawk, when the wind was nor-nor-west.

|

I have taken an entire water-rail from the stomach of the European Bittern.—Ed. |

———

BY CAROLINE F. ORNE.

———

Wild roses by the river grow,

And lilies by the stream,

And there I pulled the blossoms fair

In young love’s happy dream.

The lilies bent upon the stem

In many a graceful twine,

But lighter was the slender form

Of her I dreamed was mine.

The wilding-rose hath fairer hues

Than other flowers have known,

But lovelier tints were on the cheek

Of her I called mine own.

I pulled my love the wilding-rose,

The lily-bell so frail,

Sudden the flowers were scattered far,

Reft by the envious gale.

So from my life was reft away

Love’s flower; I dwell alone,

Far severed by relentless fate

From her I called mine own.

Still by the river blooms the rose,

The lily by the stream,

I pull no more the blossoms fair,

Fled is love’s happy dream.

———

BY ELLEN MORE.

———

“My right to love, and thine to know,

The life-stream, in its seaward flow,

Glides, chainless, ’neath the drifted snow.”

Wherever it listeth the free-born wind bloweth:

Wherever it willeth the stream of song floweth:

It revels in twin-light—its lone threads run single;

It passeth calm seas with wild Caspians to mingle.

If blest with true life-mate, in roughest of weather,

They join their glad voices and rush on together;

If lost in a lake whose fair surface is calmer,

It but hides in its bosom to warble there warmer.

If Spring lay a couch all enameled with flowers,

It lingers, enrapt, with the soft rosy hours,

And lists the wood-birds, and the meek insect-hummer,

Through the soft, growing idless of thought-teeming Summer.

And when Fall strews a carpet of brown o’er the meadow

It rests in the dusk of some mountain’s vast shadow;

Laughs out at the vain who look in for their faces,

For it mirrors great groups of the Nations and Races.

Though the Song-stream must cease all its rich, liquid flowing

When Time’s boreal breath o’er cold icebergs is blowing,

While closed the chill surface its depths who shall number,

Or the beats of its heart through the long polar slumber!

For the stream of true song hath a far-reaching mission;

It but gropeth while here, like sick sleeper in vision;

Or like volatile babe, its first word-lessons taking,

It catches faint glimpse of the vastness awaking.

As whither it listeth the free-born wind bloweth,

Wherever God willeth the true Song-stream floweth:

From all Dead Seas it holdeth its crystal wave single,

Till it riseth from earth with sky-dews to commingle.

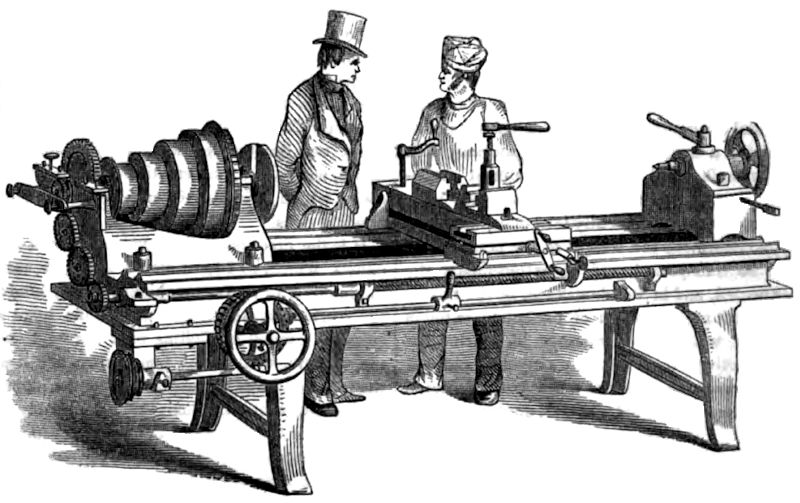

MESSRS. LEONARD, BROS. MACHINISTS.

MATTEAWAN WORKS, FISHKILL, DUCHESS COUNTY, NEW YORK.

MACHINERY DEPOT 109 PEARL AND 60 BEAVER STREET, NEW YORK.

NO. 1.—IMPROVED POWER PLANER.

Of all the leading characteristics of the present age, the most remarkable, and that which is evolving results of the greatest moment, is the general prevalence, and almost universal application of labor-saving machines, of one sort or another, which are gradually but surely bringing about a thorough revolution in all the forms of human industry.

Horse-power, man-power, nay! but almost wind and water power also, are rapidly becoming things almost obsolete and disused; while the giant might of the labor-imprisoned steam is pressed into services the most multifarious and diverse; now speeding the mighty ship with a regularity of time and pace exceeded only, if exceeded, by that of the chronometer; now whirling along, through the ringing grooves of iron, trains, the weight of which must be reckoned not by hundreds nor by thousands, but by tens of thousands of tons, measuring miles by minutes, and almost annihilating time and space; now drilling the smallest eye of the finest needle, turning the most delicate thread of the scarce visible screw, drawing out metallic wires to truly fabulous fineness, or spinning the sea island cottons of the South to threads, beside which the silkiest hair of the softest and most feminine of women waxes apparently to the thickness of a cable.

Henceforth it is apparent that of man, the worker, the skill and the slight, no more the sinews and the sweat, are to be called into requisition; that the head, and not the hand, is to be the chief instrument; that the intellectual and no longer the physical forces are to predominate, even in the merest labor.

To direct, not to wield, the power is henceforth to be the principal duty of the mechanic, even of the lowest grade; and in no respect is the progression, set in movement by the progress of science, more real than in this—that increased intelligence, increased capacity of comprehension, increased application to study, is hourly becoming more and more essential to the working-man of the present and the coming ages.

To be as strong as an elephant and as patient as a camel, with an average intelligence inferior probably to that of either animal, will no longer suffice to the swart smith, who now wields, by simple direction of a small spring or tiny lever, forces ten thousand times superior to any power that could be effected by the mightiest of sledge-hammers swung by the brawniest of human arms.

It is worthy of note, that at all periods, from the first introduction of labor-saving machinery, fears have been entertained, even by scientific men and political economists of high order, that the vast increase of working power would exert an injurious influence against the human worker; as if production were about to outrun demand and consumption, so that there would not in the end be enough of labor to be done to employ those seeking to exercise their industry or ingenuity, and depending on that exercise for the support of themselves and their families. Panics have, moreover, arisen among the workmen of the manufacturing classes, as if the machinery were about to rob them of their daily labor, whence their daily bread; and the consequences have been, especially in the large English manufacturing towns, fearful riots, conflagrations of mills and factories, destruction of much valuable machinery, the ruin of owners and employers, and—as a natural consequence of the cause last named—stagnation in business, deterioration of the laborer’s condition, and actual loss of life.

Now, it is not to be denied that on the first introduction into any factory, or class of factories, of any new labor-saving machine, by which perhaps one man is enabled to perform the work of a dozen or twenty, a large number of hands must necessarily be thrown out of work, and more or less immediate distress arise therefrom; neither is it to be admired, or held as an especial wonder, that poor men, ignorant of the operation of great principles, suffering the extremes of poverty, smarting under the idea that their right to be employed and to earn is superseded and usurped forever by the twin colossi, capital and machinery, and goaded to frenzy by the gross folly of socialist editors and journalists, should attempt to abate, what they naturally esteem dangerous and aggressive nuisances, by physical violence.

But it is certain that they do so wrongfully as regards theoretical rights, wrongfully as regards general principles and the general good, and not least wrongfully as regards their own particular welfare.

For not only is it manifestly unjust that the great mass of mankind, as consumers, throughout the universe, should be deprived of the incalculable benefit of increased supplies of necessaries at decreased prices, in order to advance the interests of a certain class of producers—not only is it manifestly absurd to dream of a return to first principles, either in arts, manufacture or science, to fancy that, once invented, elaborated and rendered public, labor-saving machinery can be abolished and thrown into compulsory disuse—but it can be shown, evidently enough, that the condition of the mechanical and manufacturing laborer is in fact improved, not deteriorated, by every successive step gained in saving labor and lowering the prices of production by the agency of machines.