Original Book Cover

CANADA

DEPARTMENT OF MINES

Hon. Louis Coderre, Minister; R. G. McConnell, Deputy Minister.

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

MEMOIR 75

No. 10, Anthropological Series

BY

Frank G. Speck

OTTAWA

Government Printing Bureau

1915

No. 1499

| PAGE | |||

| Figure | 1. | Mohegan basket gauge. | 11 |

| “ | 2. | Mohegan hand splint planer. | 11 |

| “ | 3. | Mohegan crooked knives with wood and antler handles. | 13 |

| “ | 4. | Bone punch. | 15 |

| “ | 5. | Typical basketry design of the Mohegans. | 15 |

| “ | 6. | Mohegan and Niantic painted designs. c, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. a, d, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. b, e, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan. |

17 |

| “ | 7. |

Mohegan and Niantic painted designs. a, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. b, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. c, e, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan. d, from specimen a, Pl. I, Mohegan. f, from specimen c, Pl. II, Mohegan. |

19 |

| “ | 8. |

Mohegan and Niantic painted designs. a, c, d, e, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. |

21 |

| “ | 9. |

Mohegan painted designs. a, c, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. b, Mohegan. |

23 |

| “ | 10. |

Mohegan, Niantic, and Scatticook painted designs. a, b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. c, e, f, g, h, i, k, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. d, from specimen a, Pl. II, Mohegan. j, from specimen c, Pl. II, Mohegan. l, from Curtis, Scatticook. |

25 |

| “ | 11. |

Mohegan and Niantic painted designs. a, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan. b, c, d, e, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. |

27 |

| “ | 12. |

Mohegan, Scatticook, and Niantic painted designs. a, c, from specimen (Mohegan). b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan. d, f, from Curtis (Scatticook). e, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic. |

29 |

| “ | 13. | Linear border designs from Mohegan painted baskets. | 29 |

| “ | 14. |

Body designs from Mohegan painted baskets. a, on the top of the basket; b on the sides. |

31 |

| “ | 15. | The curlicue or roll, in Scatticook baskets. | 33 |

| “ | 16. | The curlicue or roll, in Scatticook baskets. | 35 |

| “ | 17. | Bottom of Scatticook basket, showing trimming of radial splints. | 37 |

| “ | 18. | (a) Scatticook gauge. | 39 |

| (b) Scatticook gauge. | 39 | ||

| “ | 19. | Scatticook gauges. | 41 |

| “ | 20. | Scatticook splint planer. | 43 |

| “ | 21. | Mohegan beadwork on birch bark. | 43 |

| “ | 22. | Carved bone hand. | 43 |

| “ | 23. | Decorated Mohegan wooden object. | 45 |

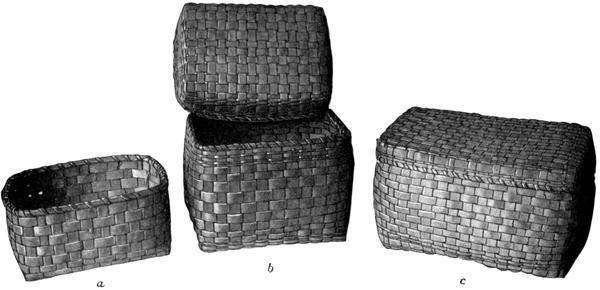

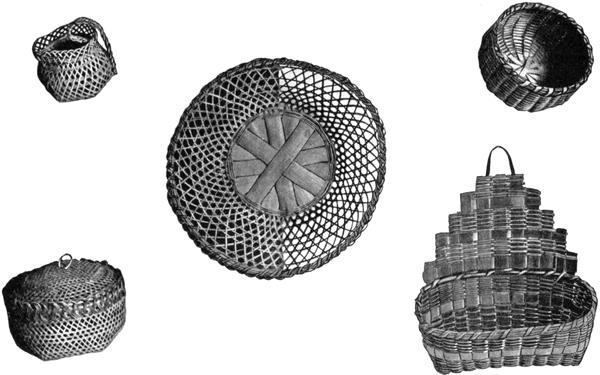

| Plate | I. | Mohegan baskets (a and b painted). | 49 |

| “ | II. | Mohegan baskets (a, b, and c painted). | 51 |

| “ | III. |

Mohegan baskets. a—Painted. b—Shows bottom construction. |

53 |

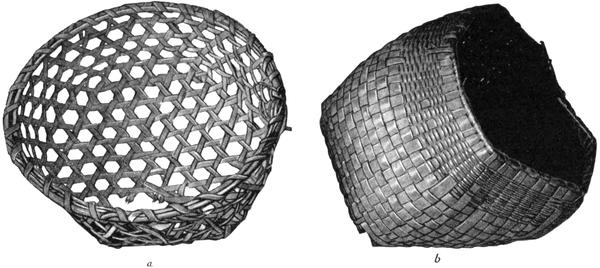

| “ | IV. |

Niantic and Mohegan baskets. a—Mohegan washing basket, b—Niantic storage basket made about 1840 by Mrs.Mathews at Black Point (near Lyme, Conn.) |

55 |

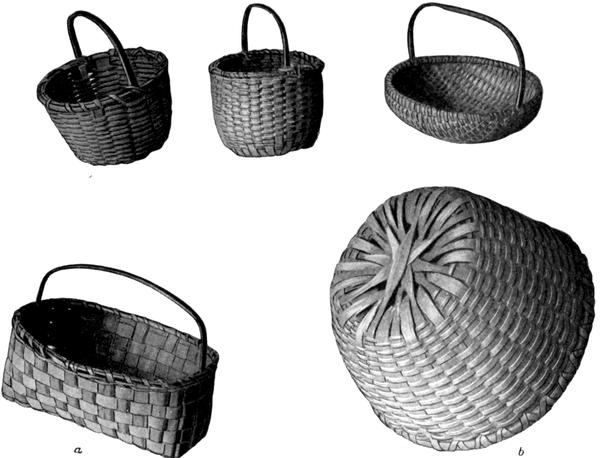

| “ | V. | Mohegan carrying baskets. | 57 |

| “ | VI. | Mohegan baskets, fancy work baskets, and wall pocket. | 59 |

| “ | VII. | Tunxis baskets. Made by Pually Mossuck, a Tunxis woman from Farmington, Conn., who died about 1890 at Mohegan. Lower left hand basket slightly painted. | 61 |

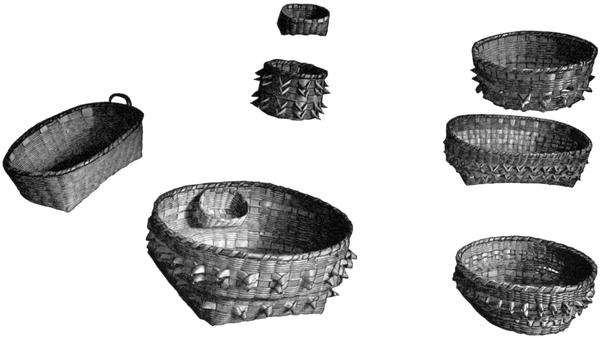

| “ | VIII. | Scatticook baskets, made by Rachel Mawee, Abigail Mawee, and Viney Carter, who died at Kent, Conn. about 1895. | 63 |

| “ | IX. | Oneida stamped basket (Heye collection). | 65 |

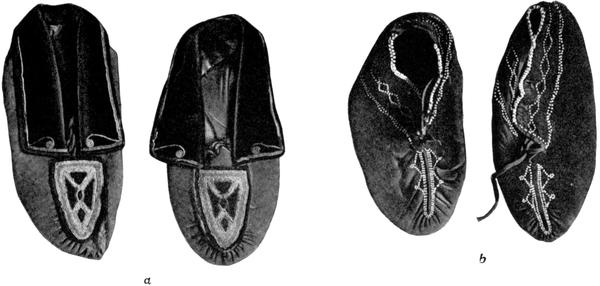

| “ | X. |

Mohegan and Niantic moccasins. a—Mohegan moccasins. b—Niantic moccasins from the old reservation at Black Point, near Lyme, Conn. |

67 |

| “ | XI. | Mohegan and Niantic beaded bags (3 from the Heye collection). | 69 |

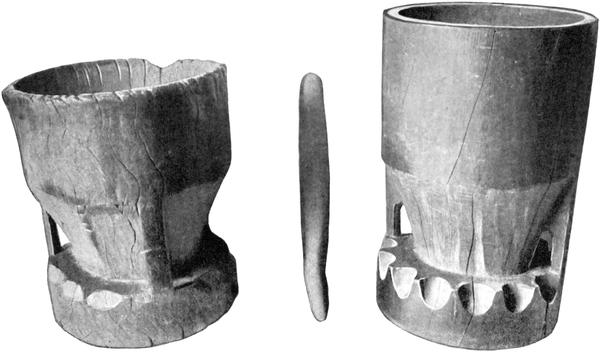

| “ | XII. | Mohegan corn mortars and stone pestle. | 71 |

| “ | XIII. | Mohegan ladles and spoons. | 73 |

A fortunate phase of the research work among the Indians of New England has recently led to the extension of our knowledge of the decorative art of the eastern Algonkin tribes. This has been made possible by the discovery of specimens, and by information furnished by several aged Indians of the Mohegan and Niantic tribes of eastern Connecticut.[1]

During several visits in the winter of 1912–13, Mrs. Henry Mathews (Mercy Nonsuch), the only full-blooded survivor of the Niantic Indians, formerly inhabiting the shore of Long Island sound around the mouth of Niantic river, and the Mohegans, Cynthia Fowler, Charles Mathews, and the late Fidelia Fielding, the last person who could speak the Mohegan language, all contributed towards the material here presented.[2]

The principal field of decoration among the Mohegan and Niantic, so far as we can now tell, seems to have been chiefly in paintings on baskets. Decorative wood-carving upon household utensils and sometimes upon implements was also quite common. Bead-work, on the other hand, appears to have been a secondary activity. A short account of the basket-making itself is required, before the basket decorations are described. For household and gardening purposes these people have developed a few types[Pg 2] of baskets (manu·´da[3] “receptacle”) varying in shape, size, and weave. The most characteristic forms seem to have been rectangular baskets a foot or so in length, two-thirds as high, and of proportionate width, and without handles, though often provided with covers. These are the household storage articles (Plates I and II). For carrying garden products, and for hand use in general, are somewhat smaller round-bottomed baskets, with handles or bails, ranging in width from 4 inches up to baskets with a capacity of half a bushel (Plates III and V). Then we have the type known, among the Indians from Nova Scotia to the Southern States, as “melon”, “rib”, or “gizzard” baskets (Plate III, upper right hand corner), provided with bails, and also used for carrying. And, lastly, there are the open work baskets, some of which are small fancy articles, while others are used as strainers (Plates IV and VI). These fall under the general type of open hexagonal twill baskets. All these types, of course, are commonly found among practically all the tribes of the Atlantic coast, varying only in the minor details of weave at the rim and the bottom.

As to the materials, the Mohegan and Niantic, like the northern New England tribes, used prepared splints of the brown ash. Next in importance is the white oak. Here the pounding is unnecessary, the splints being more easily freed from the log. Swamp maple is also commonly used by the Mohegan basket-makers, although it is not as durable as either the oak or the ash.

All these materials go through the same processes of preparation before the splints are ready to be woven. The first stage in the process consisted in pounding the ash log all over, and then separating the layers of wood. Next, the lengths of splints were shaved smooth with a spoke-shave, which looks like a European tool. Hand gauges were then used to cut the splints into strips of uniform width. These gauges (Figure 1), not unlike those of the Penobscots, were provided with teeth made,[Pg 3] in recent days, of clock springs; the width of the splint depending upon the distance at which the teeth were set in the end of the gauge. Another small implement, a sort of hand planer through which the splint was drawn to make it finer, was also obtained at the Mohegan village (Figure 2). The knives of the crooked type, bən·ī·´dwaŋg (Figure 3), used by the Mohegans for woodworking in general, have a very pronounced curve, and are usually mounted on wooden or sometimes buckhorn handles. While not necessarily used directly in basket making, these knives are indispensable to the Indian workman. A very old bone pointed tool, probably a punch (Figure 4), seems to have been used in some way, perhaps in weaving the basket rims.

The ordinary weave among these tribes is the common checker-work. The basket bottoms are of two kinds, rectangular and round. In the rectangular bottoms the checker-work forms a foundation, the same process continuing up the sides. In the round-bottomed forms the splints are arranged like the spokes of a wheel crossing and radiating from a centre. These splints turn upwards around the bottom, and form the standards around which the side filling is woven, in the under-one-over-one-process. Among the Mohegans a certain feature of the round-bottomed types occurs which has not yet been found in other tribes making similar baskets; that is, the broad flattened centre standards of the bottom, appearing in Plate III, figure b. The ordinary New England oak or maple hoops, one inside and the other outside, bound down by a splint in the ordinary manner of wrapping, constitute the rims of all the baskets. The second type of round baskets is called “gizzard” basket by the Mohegans (Plate III, upper right hand corner). These are generally made of oak, and their weave, although shown plainly in the illustration, is almost impossible to describe.

The decorations upon baskets are produced in two ways, either by running variously coloured splints into the weaving as fillers round the sides, or by painting with pigment upon broad splints various patterns extremely free in outline and quite independent of the technique. It is with such painted designs that we have chiefly to deal, because they perpetuate the native decorative art of these Indians. The colours appearing[Pg 4] upon the baskets are red (skwa´yo), black (sug·a´yo), and indigo (zi·wamba´yo), the commonest being red and black. The red is obtained by boiling down cranberries. The black dye has now been forgotten, although some think that it was either ‘snakeberries’ (or ‘poke-berries,’ termed skuk), or perhaps huckleberries. In later times they have used either water colours or blueing. The colours were applied by means of crude brushes, made by fraying the end of a splinter of wood, or by using a stamp cut from a potato, which is dipped into the colouring matter and then stamped on the splints.

The designs themselves in the field of basketry decoration are pre-eminently floral, the figures being highly conventionalized. The main parts of the blossom are pictured. The corolla of the flower forms the centre, surrounded by four petals, and commonly augmented by four corner sprays apparently representing the calyx from underneath brought into view. There is a fundamental similarity in these pseudo-realistic representations occurring on all the different baskets, which shows that this was the prevailing motive in this kind of decoration. The corolla usually occupies the exposed surface of one splint, and the four petals occupy the surrounding ones, as is shown in the natural size illustration (Figure 5). The colours in this specimen are limited to blue and red. Cynthia Fowler, a Mohegan informant, named the flower the “blue gentian”; but how generally this name was used in former times it is impossible to say. These flowers are usually found enclosed within a larger diamond-shaped space, on one side of the basket, the enclosing border consisting of a straight line or chain-like line edged by dots. These dotted borders and the flower elements are very characteristic of Mohegan and Niantic work. The corners of the baskets from top to bottom also constitute another favourite field of ornamentation. Here vertical alternating chain-like curves of several types appear. Examples of the available designs of both sorts are shown in Figures 6 to 14. The solid black in the sketches represents either black or dark indigo of the actual design; the lined spaces represent red.

Turning to the design reproductions (Figures 6, 7, 8, 9), we observe a most consistent similarity in all those of the rosette[Pg 5] type, to wit, the conventional centre, the radiating petals, and the enclosing diamond or four-curve, recurring with modifications in practically all of such designs. Some are very handsome, a few rather colourless. The dotting is very distinctive. Next are the line or border patterns, which, although adapted to linear spaces, are characterized, like the rosettes, by intertwined lines, dots, and petals. Frequently different rosettes appear on each of the four sides of the same basket; and the sides are also occasionally quartered diagonally by one of the border or line patterns, and are thus divided into triangular areas, each containing a rosette. Unfortunately none of the painted figures show in the photographs, on account of their having become quite faint through age and wear.[4]

In this whole series of conventional painted patterns a general resemblance to northeastern Algonkin designs, as far north as the Naskapi of Labrador, is very noticeable. It is, moreover, quite likely that similar designs among the Narragansetts were referred to by Roger Williams when he wrote, “They also commonly paint these (skin garments, etc.) with varieties of formes and colours.”[5]

A further extension of the ubiquitous splint basketry of the New England tribes, and the decorative work connected therewith, is furnished by another Connecticut tribe—the Scatticook, of the Housatonic river, near Kent. Their art is especially interesting, because it has also just become extinct among their descendants here. As a tribe the Scatticook (Pisga´‛tiguk, ‘At the fork of the river’) were composed of exiled Pequots, Mohegans, and the remnants of western Connecticut tribes who formed a new unit in their new home.[6] Their type of culture was accordingly intermediate in some respects between the eastern Connecticut tribes and those of the Hudson river.

To judge from a vocabulary which I obtained at Scatticook about ten years ago, they had closer linguistic affinities with the Hudson River (Delaware) group.

Until ten years ago the native art of basketry was preserved by the Scatticooks, and some specimens were then collected during several visits. It was found recently, in another visit to the tribe, that the industry had become extinct; so our remarks are now based upon old specimens and implements in the possession of the Indians. The general character of Scatticook work is the same as that of the Mohegans. Instead of the maple, however, the Scatticook used white oak or brown ash. The method of preparing the splints was the same, as was also the case with the types of weaving (Plate VIII). In the round-bottom forms we notice the same flat radiating splints cut narrow at the edge, as figured before in dealing with Mohegan work. The Scatticook baskets are, as a whole, quite finely constructed of very thin splints. One somewhat distinctive feature is found here, namely, the very frequent use of the curlicue or roll as an ornamental feature. The curlicue consists of a splint run over one of the warp splints and twisted between two alternate standards, thus making a sort of twisted imbrication. The Scatticook, considering the embellishment as representing a shell, call it “a shell”; and they term the baskets with this feature “shell-baskets” (Figures 15, 16, 17).

Three modifications of this ornamentation are shown in Figures 15, 16, a and b; in Figure 16, a, the splint is twisted alternately between two rows of warp at a different level; in Figure 15, the splint is curled twice in a different direction, and forms a point; in Figure 16, b, the splint is twisted once between two parallel rows of warp. This is claimed by the Indians to be a native feature; and, since it is found in the oldest baskets from the region, there seems little doubt that it is aboriginal.

The Scatticook seem to have employed almost exclusively pokeberry juice to stain the basket splints dark blue. In none of the specimens made in recent times do we find the painting upon the splints, as is the case among the Mohegans. The only record of this kind of work from the Scatticook is found in an[Pg 7] article by W. S. Curtis,[7] describing a collection of old baskets obtained many years ago.

The gauges made by these people are somewhat distinctive (Figures 18 a and b, and 19). One of their characteristics is that the decorations are largely functional, the object in the maker’s mind evidently having been to provide a firm grip for the operator and at the same time to produce a decorative effect. This interesting feature is noticeable in the few specimens that were discovered on the reservation, and in several others in the possession of collectors. They are all highly prized by their possessors. In one case there seems to have been an attempt to portray a fish on the handle. Another instrument, a knife used in shaving the splints, is shown in Figure 20.

While we may assume that some influence upon the art of the Connecticut Indians resulted from contact with the Iroquois, there is nothing to show that the former had such symbolic associations in their designs as did the Iroquois.[8] The general similarity of the Connecticut Indian decorations to those of both the Iroquois and the northeastern Algonkins is really too ambiguous to permit a final decision as to their affinities. Aware of these uncertainties, I feel, however, that the evidence sustains the conclusion that the stamped and painted designs are original to the southern New England Indians, and that they spread from them to the Iroquois.

The occurrence of identical types of splint basketry and similar potato stamp decorations among the Oneida (Plate IX) and Onondaga,[9] might lead to the impression, were we to overlook resemblances with northern Algonkin designs, of an Iroquoian origin for the whole technique. In a recent visit, however, to the Cherokee of North Carolina, for the purpose of tracing relationships between northern and southern art motives,[Pg 8] nothing was discovered comparable to these northern types either in design or technique, although the eastern Cherokee are quite conservative. This naturally leaves the art of the southern New England tribes to be tentatively classified as a somewhat distinctive branch of the northern and eastern Algonkin field, with some outside affinities.

From information and sketches furnished by Dr. J. Alden Mason, based on studies and photographs which he made of New England baskets in the C. P. Wilcomb collection, Oakland, Cal., it seems that similar stamped splint baskets were found among the Indians as far as the Merrimac River valley in southeastern New Hampshire. Specimens in the collection referred to are supposed to have come from Union, Me., Lenox, Mass., Ipswich, Mass., and Herkimer, N.H. While not numerous enough to permit of discussion, the specimens from this eastern extension of the stamped or painted basket area show a type of design different from that of our southern New England tribes. The patterns are less elaborate. Although it is difficult to account for it, they seem to bear closer resemblances to the designs on Oneida baskets.

North of the southern New England culture sub-area, which appears to have terminated at the Merrimac river, splint basketry and painted designs were replaced by the birch bark basketry and etched designs characteristic of the art of the Wabanaki group.

A few examples of Mohegan and Niantic beadwork have survived the decay of Indian culture in New England. These miscellaneous articles are shown in Plates X and XI. They include moccasins, bags, and portions of costume. Whether they have all been actually made by Mohegans is not certain, except where indicated. One peculiarity of Mohegan art is beadwork upon birch bark. A couple of very old specimens (Figure 21) of this work have come to light. The foundation is the thin bark of the white birch. The beadwork figures are practically all floral, though a few geometrical designs occur; and realism appears as in the butterfly representation. The floral designs seem to be somewhat related to those found in the basket paintings, although they are not so aboriginal in appearance.[Pg 9] The beadwork designs are generally termed “forget-me-nots,” “daisies,” “yellow daisies,” with buds, leaves, and stems. It should be noted in this connexion that from the earliest time the Mohegans have had some contact with Iroquois, especially the Mohawks, who from time to time visited the Connecticut Indians in small parties. During the early nineteenth century a number of the latter joined the Iroquois, with whom an intermittent relationship has since been maintained. It may be said in general, however, that the same type of floral beadwork extends throughout the whole northeastern and Great Lakes area, in which the Mohegan work may be included. Almost identical bags, for example, both in form and design, come from the Mohegan, Penobscot, Malecite, Montagnais, and Ojibwa.

In the carving of wooden utensils, such as bowls, spoons, mortars, and miscellaneous articles, the Mohegans have shown considerable skill, as appears from what few articles have survived among them. Some of their bowls made from maple burls are exquisite. Several of these have been described and illustrated by Mr. Willoughby in a recent paper, the originals being in the Slater Memorial Museum, of Norwich. Wolf or dog faces facing inward from projections upon the rim are very well executed. Oftentimes such bowls were decorated by inserting wampum beads into the wood, giving the outline and eateries of the face. These bowls were used until a few generations ago for mixing native bread known as johnny-cake.

Hardly inferior in workmanship to the bowls are the very distinctive Mohegan mortars (də´kwaŋg, “pounder”) made of a pepperidge log, and provided with long stone pestles (gwu´nsnag, “long stone”). Three of these specimens, now in the Heye collection, are shown in Plate XII. Practically all of the large mortars for grinding corn in the household, among the Mohegans, were of this type. Their sides were tapered toward the pedestal, and there were from two to three handles on the sides near the bottom. Hollowed scallop work ornamented the edge of the pedestal. The mortars average about 17 inches in height; and their cavity, narrowing towards the bottom, is very deep. The stone pestle is 18 inches long. Until lately a few of these[Pg 10] heirlooms were cherished in several Mohegan families.

The use of wooden spoons and ladles (giya´mən) has not been entirely abandoned by these Indians. The designs of most of the forms are considered as aboriginal. They have rather broad oval—or sometimes even circular—bowls, sometimes flat-bottomed bowls; and the handles are of varying lengths, with rounded projections in the under side to prevent the ladle from sliding down into the pot. This favourite semi-decorative and functional feature also occurs in the handles of gauges (Figure 1). The spoons are usually made of birch or maple. One or two ornamentally carved specimens were found. One with a dog’s head at the end of the handle, and the bowl set at an angle to the handle, is in the Slater Museum. Another, recently obtained from the Indians (Plate XIII), has two human faces, back to back, at the end of the handle. The spoons range from 6 to 12 inches in length. Various types are shown in Plate XIII.

Several articles of bone, ornamentally carved, have come to light. Chief among these are whalebone canes, with skilfully made carvings. The handle of one of these canes represents a very natural looking human hand (Figure 22). This same figure has been met with in the carvings of the Penobscot and Iroquois.

A few miscellaneous articles made by old Mohegan workmen have been discovered during the investigation, one of which is covered with decorative designs (Figure 23). No discussion is warranted, since any possible interpretation has now been forgotten, even as to the function of the object.

Strange as it may seem to find definitive material amid such deculturated surroundings, there can be little doubt that these tribes have preserved designs of considerable antiquity. Perhaps they belong to an early type of eastern Algonkin art, consisting of curves, circles, ovals, wavy lines and dottings forming floral complexes, having a general distribution in the north and east, from which the more elaborate realistic floral figures of beadwork have developed.

Figure 1. Mohegan basket gauge.

Figure 2. Mohegan hand splint planer.

Figure 3. Mohegan crooked knives, with wood and antler handles.

Figure 4. Bone punch.

Figure 5. Typical basketry design of the Mohegans.

Figure 6. Mohegan and Niantic painted designs.

c, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

a, d, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

b, e, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan.

Figure 7. Mohegan and Niantic painted designs.

a, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

b, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

c, e, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan.

d, from specimen a, Pl. I, Mohegan.

f, from specimen c, Pl. II, Mohegan.

Figure 8. Mohegan and Niantic painted designs.

a, c, d, e, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

Figure 9. Mohegan painted designs.

a, c, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

b, Mohegan.

Figure 10. Mohegan, Niantic, and Scatticook painted designs.

a, b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

c, e, f, g, h, i, k, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

d, from specimen a, Pl. II, Mohegan.

j, from specimen c, Pl. II, Mohegan.

l, from Curtis, Scatticook.

Figure 11. Mohegan and Niantic painted designs.

a, from specimen b, Pl. I, Mohegan.

b, c, d, e, f, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

Figure 12. Mohegan, Scatticook, and Niantic painted designs.

a, c, from specimen (Mohegan).

b, from specimen a, Pl. III, Mohegan.

d, f, from Curtis (Scatticook).

e, from specimen b, Pl. IV, Niantic.

Figure 13. Linear border designs from Mohegan painted baskets.

Figure 14. Body designs from Mohegan painted baskets; a, on the top of the basket; b on the sides.

Figure 15. The curlicue or roll, in Scatticook baskets.

(a)

(b)

Figure 16. The curlicue or roll, in Scatticook baskets.

Figure 17. Bottom of Scatticook basket, showing trimming of radial splints.

Figure 18 (a). Scatticook gauge.

Figure 18 (b). Scatticook gauge.

Figure 19. Scatticook gauges.

Figure 20. Scatticook splint planer.

Figure 21. Mohegan beadwork on birch bark.

Figure 22. Carved bone hand.

Figure 23. Decorated Mohegan wooden object.

Explanation of Plate I.

Mohegan baskets (a and b painted.)

Plate I.

Explanation of Plate II.

Mohegan baskets (a, b, and c painted.)

Plate II.

Explanation of Plate III.

Mohegan baskets.

a—Painted.

b—Shows bottom construction.

Plate III.

Explanation of Plate IV.

Niantic and Mohegan baskets.

a—Mohegan washing basket.

b—Niantic storage basket made about 1840 by Mrs. Mathews at Black Point

(near Lyme, Conn.)

Plate IV.

Explanation of Plate V.

Mohegan carrying baskets.

Plate V.

Explanation of Plate VI.

Mohegan baskets, fancy work baskets, and wall pocket.

Plate VI.

Explanation of Plate VII.

Tunxis baskets. Made by Pually Mossuck, a Tunxis woman from Farmington, Conn., who died about 1890 at Mohegan. Lower left hand basket slightly painted.

Plate VII.

Explanation of Plate VIII.

Scatticook baskets, made by Rachel Mawee, Abigail Mawee, and Viney Carter, who died at Kent, Conn., about 1895.

Plate VIII.

Explanation of Plate IX.

Oneida stamped basket (Heye collection.)

Plate IX.

Explanation of Plate X.

Mohegan and Niantic moccasins.

a—Mohegan moccasins.

b—Niantic moccasins from the old reservation at Black Point, near Lyme,

Conn.

Plate X.

Explanation of Plate XI.

Mohegan and Niantic beaded bags (3 from the Heye collection.)

Plate XI.

Explanation of Plate XII.

Mohegan corn mortars and stone pestle.

Plate XII.

Explanation of Plate XIII.

Mohegan ladles and spoons.

Plate XIII.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A few baskets made by an old woman, named Pually Mossuck, of the Tunxis tribe (in the vicinity of Farmington, Conn.) were incidentally obtained. A number of years ago this woman died at Mohegan, the last of her people. This entire collection is now in the possession of Mr. George G. Heye.

[2] In previous papers the writer has already published other ethnologic notes on the Mohegan and Niantic tribes. See Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History (N.Y.) vol. III, pp. 183–210 (1909), where are also listed papers in collaboration with Prof. J. D. Prince on the Mohegan language.

[3] · indicates that preceding vowel or consonant is long; ‛ indicates breathing following vowel; ´ indicates main stress; ə, like u of English but; ŋ, like ng of English sing; other characters used in transcription of Indian words need no comment.

[4] I am indebted to Mr. Albert Insley for his careful work in deciphering and reproducing the designs on these baskets.

[5] Cf. Roger Williams, A Key into the Language of America, London, 1643 (reprinted by the Narragansett Club), p. 145 and p. 206.

[6] Cf. article in Proceedings of American Philosophical Society, vol. XLII, No. 174 (1903), by J. D. Prince and F. G. Speck; also De Forest, History of the Indians of Connecticut.

[7] ‘Basketry of the Scatticooks and Potatucks,’ Southern Workman, vol. XXXIII, No. 7, 1904, pp. 383–390.

[8] Cf. A. C. Parker, American Anthropologist, N.S., vol. 14, No. 4, 1912, pp. 608–620.

[9] Specimens in the collection of the American Museum of Natural History, New York City. I also learned of the same decorations among the Iroquois at Oshweken, Ontario, and the Mohawks of Deseronto.

Transcriber’s Note:

This e-text is based on the 1915 edition. Punctuation errors have been tacitly removed. The following typographical errors have been corrected:

# p. 3: l. 20/21: “under-one over-one-process” → “under-one-over-one-process”

# Footnote 7: “Scattacook” → “Scatticook”

# Caption for Figure 20: “Satticook” → “Scatticook”

For transliteration of the Mohegan language special pronunciation characters are used in the original text. These characters are specified by the following descriptive terms (cf. Footnote 3):

# ə—schwa: “inverted e”

# ŋ—eng, or engma:“ng”

# ī—“i with macron above”