A FIGURANTE.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation and spelling have not been corrected. Punctuation has been silently corrected. A list of other corrections can be found at the end of the document.

A FIGURANTE.

"Go the whole figure."—Sam Slick.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

1844.

LONDON:

R. CLAY, PRINTER, BREAD STREET HILL.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

"Good wine needs no bush," and, therefore, little by way of preface is necessary to this Work. "He who is ignorant of arithmetic," says Archimedes, "is but half a man." Therefore, for the sake of manhood, which drapers'-boys and lawyers'-clerks attempt by means of mustachoes and penny-cigars, read this Work,—for if the dead abstractions of this science will make a man, what must the living realities do?—Nothing less than a Phœnix D'Orsay, which is at least 1 man ¾ and ⅝.

Read this book, then, my friends, young and old. It teaches practical philosophy in every [2] chapter; wisdom in every page; and common sense in every line. Get this manual at the fingers' ends of your mind, and your physical and mental powers will be so expanded that you will be able to catch a comet by the tail; take the moon by the horns; knock down the great wall of China, à la Cribb; or measure the spectre of the Brocken for a pair of breeches, and thus cut a pretty Figure.

Arithmetic is the art or science of computing by numbers. It is national, political, military, and commercial. It is of the highest importance to the community; because it pre-eminently teaches us to take care of Number I. Our ministers succeed according to their knowledge of the science of numbers. Witness the skilful management of majorities of the lower house.

He who understands the true art of Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, and Division, as here laid down, will not be considered a mere cipher in [4] the world; but will, in all probability, make a considerable figure: and in the figurative words of Horace, be "Dives agris dives positis in fœnore nummis."

Let us, therefore, under the guidance and protection of that god of honest men, the light-heeled and light-fingered Mercury, be diligent so to add to our store by subtracting from the stores of others, that we may add to our importance. Let us so multiply our resources, by encouraging division among our contemporaries, that we may see their reduction in the perfection of our own practice.

EQUALITY.

"WHO ARE YOU?"

= Equality. The sign of equality: as, "A living beggar is better than a dead king;" or both being dead, are equal to each other.

— Minus, less. The sign of subtraction; as, for instance, an elopement to Gretna; or, a knocking-down argument by the way-side, — minus ticker. Take from — from take.

A PLURALIST.

+ Plus, or more. The sign of addition; as, 3 livings + to 1 = 4; or, 5 millions of new taxes + to 48 = 53.

THE SACRED HALTAR.

× Multiplied by. The sign of multiplication: as, "The sun breeds maggots in a dead dog."—See Shakspeare. Or, "Money makes money."—See Franklin. Or, Anti-Malthus.—See Ireland.

DIVIDING THE CHINESE, A CUTTING JOKE.

÷ Divided by. The sign of division. Example [8] 1. The Whigs.—2. The Church. A house divided against itself. Division of property; the lion's share, &c.

Is to: so is:: As Lord B—— is to Bishop P——, so is a blue musquito to a planter's nose.

As Sir R—— I—— is to J—— H——, so is a pair of donkey's-ears to a barber's-block.

As Tommy Duncombe is to Lord Stanley, so is shrimp-sauce to a boiled turbot.

THE POOR CURATE. THE BISHOP.

Numeration teaches the different value of figures by their different places (see Walkinghame, Court Guide, Law List, &c.); also the value of ciphers, or noughts, according to their relative situations (see Intellectual Calculator, or Martin's Arithmetical Frames). As regards the value of figures in places, we have illustrations in sinecures [10] of all grades, from the Lords of the Treasury to the meanest underling of the Stamp-Office.

Place and pension make the unit a multitude, according to the position of the noughts,—that is, that large portion of the public called the nobodies. The more a man is surrounded by his inferiors, the greater he becomes. Hence the necessity of restrictive tariffs to prevent wealth in a community,—and of impediments to education. It is not, therefore, naughty for our betters to keep us down by any kind of mystification; as the sun always looks larger through a fog.

The value of figures and of ciphers will be well understood in the following table, which ought to be committed faithfully to memory. It will be seen that when the noughts, the nobodies, that is, the people, go before the legislative units, their value is consequently decreased; but when they follow as good backers in good measures, the value of the characters is increased ad infinitum.

| The good old times. | ||||

| P E O P L E . | – | 1 | King. | |

| 20 | Lords. | |||

| 300 | Tithe-eaters. | |||

| 4000 | Quarrel-mongers (lawyers). | |||

| 50000 | Men-killers (army). | |||

| 600000 | Land-swallowers (landlords). | |||

| 7000000 | Dividendists. | |||

| 80000000 | Pensioners. | |||

| 900000000 | Sinecurists. | |||

| The new system, or march of intellect. | ||||

| King | 100000000 | – | P E O P L E . | |

| Lords | 20000000 | |||

| Tithe-eaters | 3000000 | |||

| Quarrel-mongers | 400000 | |||

| Land-swallowers | 50000 | |||

| Dividendists | 6000 | |||

| Men-killers | 700 | |||

| Pensioners | 80 | |||

| Sinecurists | 9 | |||

Our life is an addition sum; sometimes long, sometimes short; and Death, with "jaws capacious," sums up the whole of our humanity by making the "tottle" of the whole.

Man is an adding animal; his instinct is, to get. He is an illustration of the verb, to get, in all its inflexions and conjugations; and thus we get and beget, till we ourselves are added to our fathers.

There are many ways of performing addition, as in the following: a young grab-all comes upon the fumblers at long-taw, as Columbus did upon the Indians; or, as every thrifty nation does upon the weak or unsuspicious, and cries "Smuggins!"

[13] Addition is also performed in a less daring manner by the save-all process, till Death, with his extinguisher, shuts the miser up in his own smoke.

A SAVE-ALL.

Addition may also be performed by subtraction by other methods. It is one to make "Jim along Josey!" the watchword, as Joey does in the pantomime.

MIHI CURA FUTURI.

Addition teaches, also, to add units together, and to find their sum total, as A + B = 2. A bachelor is a unit; a Benedict, unitee.

Matrimonial Addition.—By common ciphering 1 and 1 make 2. But, by the mathematics of matrimony, 1 and 1 will produce from 1 to 20, arranged in row, one above another, like a flight of [15] stairs. They make a pretty addition to a man's effects, as well as to his income; and, if not themselves capital, are a capital stimulus to exertion. Surrounded by these special pleaders, a man becomes as sharp-set as a Lancashire ferret, and looks as fierce as a rat-catcher's dog at a sink-hole. Such men ought to be labelled, "Beware of this unfortunate dog!" for he would bite at a file!

A MAN OF MANY WOES.

Adding to your name.—This is another mode of performing addition. It is not necessary to go [16] to an university for this, any more than it is necessary to go to a church to get married. The thing can now be done without it. Schoolmasters, and pettifoggers of all kinds, will find this an excellent piece of practical wisdom.

To go back a little to first principles, which should never be lost sight of in the teaching of any art or science, we must set forth the grand leading rule before our pupils. Addition teaches, therefore,[19]

The man who takes care of No. 1.

Subtraction teaches to "take from" or to find the difference of two numbers; having taken too much in, and slept out; to find the difference in sovereigns and shillings between that and sleeping at home according to the "conventional laws of virtuous propriety." (Vide Miss Martineau.)

The figures are to be arranged in subtraction one under the other; that line expressing the [24] highest number, being placed above the line expressing the smaller number. In this arrangement, the upper line is called the subtrahend, and the lower the subtractor; the difference is called the remainder. Our readers, the million, are the subtrahend. The following are subtractors:—

The Rule of Subtraction is perhaps the most useful in either national, political, or commercial Arithmetic; "Take from" being the universal maxim of mankind from the day that Adam and Eve stole the forbidden fruit. In sacred history we find various exemplifications of the principle: Jacob made use of it when he obtained his brother's birthright and his blessing; David, when he took the wife of Uriah. Profane or classical history abounds with examples. It was the royal and sacerdotal rule, in all climes, countries, and [25] times. Kings have grown thrifty by it, and conquerors invincible. "Take from" is, in short, the motto of the legislators; and rhetoric the soldier's watchword, the prince's condescension, the courtezan's smile, the lawyer's brief, the priest's prayer, and the tradesman's craft. The use of this rule, is to enable us to "do one another," not "as we would be done," without the contravention of the majesty of the law.

We have had some amusing ways of performing this rule in "by-gone ages." Among the most celebrated, were Indulgences and Benevolences. They worked well for those who worked ill, and led to a multiplication of heresies.

Subtraction is perhaps one of the most fashionable of all the rules; and any one who sets himself down for a gentleman must expect to be beset by a swarm of hungry locusts, who make a rule to bleed him at every pore till he becomes poor. When Edward the First took the wealth of the Jews and their teeth at the same time, he showed a fatherly consideration for those who having nothing to eat wanted neither incisores, cuspidati, bicuspidæ, or molarii. But we are to be nipped, and squeezed, and tapped, and leeched, and drained to all eternity, and are still expected to—give.

To take in.—This rule not only teaches us to take from, but also to take in, which is to take from, with true tact and skill. England is the [27] Land of Goshen in this particular, and Smithfield the focus of the art, whence the first rule for selling a horse is—

TAKEN IN AND DONE FOR.

"who steals MY purse steals trash."

The rules already given for performing this branch of arithmetic apply to money matters; but the perfection of the art consists, not in simply taking from another what you want yourself, but that which does not enrich you, but makes him poor indeed. This has been styled, by way of eminence, the devil's subtraction, being the general essence of the black art. It is called Detraction.

[29] Detraction may be performed in a variety of ways, as for example:—"Oh, I know him—his great grandfather was—but no matter, and his mother—no better than she should be, but I hate to speak evil of the dead. I have enough to do to mind my own business—and yet one cannot help knowing—but yet nobody knows what he is or how he gets his money. He makes a show certainly, but I like things to be paid for before they are sported. His wife, too—what was she, do you suppose? As I have heard, a cook in a tradesman's family.—Well, a cook is not so bad after all—I am sure it is better than a doctor. But I believe he was forced to marry her.—Poor woman, she suffered, I dare say—Well, it is well it is no worse—It was the only amends he could make her—It would have been a cruel thing for the poor innocent children to be born illegitimate.—But he is still very gay—These sort of men will be—but there will be an exposé some day. Things can't go on for ever—Well, I wish them no harm, poor creatures—But do you go to their party to-night?—I go only for the sake of seeing how madam cook conducts the entertainment."

[30] Rule for Ladies With Regard To Their Rivals.—Should any lady be so unfortunate as to fear a rival in the affections of some simple-hearted swain in the personal attractions of some youthful beauty whom he has never seen, it must be her method not to vilify her character or underrate her accomplishments,—no, this is but sorry skill. The more delicate and refined way of subtracting from her merits will be to employ unbounded panegyric, so as to raise the expectations of the feared admirer, that the real shall fall infinitely short of the ideal. This is another mode of performing subtraction by addition.

Literary Subtraction.—This is of essential service to editors, reviewers, and others, who, having nothing good of their own with which to amuse the public, steal the brains of others.

Rule.—Take from a work published at a guinea all its cream and quintessence, under pretence of praising it into immortality through the pages of your fourpenny review. "Castrant alios, ut libros suos per se graciles alieno adipe suffarciant."

[31] Mercantile Subtraction.—It is well understood in this country, that no honest man can get a living, in consequence of the extraordinary competition among us. It is therefore considered legal and justifiable for the baker to "take toll" and make "dead men;" for the licensed victualler to make "two butts out of one;" for the wine-merchant to "doctor" his port; for the butcher to "hang on Jemmy;" for the printer to make "corrections;" for the tailor to "cabbage;" for the grocer to "sand his sugar and birch-broom his tea." The milkman "waters his milk" by act of parliament; and to show that all this is in the order of Providence, the rains of heaven wet the coals.

National or Political Subtraction.—There is one part of the New Testament which all Christian rulers have religiously observed, namely, "Now, Cæsar issued a decree that all the world should be taxed." The art of taxation is, therefore, not only a religious obligation, but is the science of sciences and the most important part of National Arithmetic.

Taxation is necessary just as blood-letting is necessary in plethora. Over-feeding produces a [32] determination of the blood to the head, and then radical rabidity breaks out into rebellion. Over-feeding requires bleeding. There is a tendency in every industrious nation to get on too fast. Taxation is the fly-wheel which softens and regulates the motion of the national machinery, the safety valve which prevents explosion, while that accumulation of taxation called the dead weight is a "clogger" to keep things down.

Whenever there is a "rising," it is a sure sign that taxation is too light; consequently taxation should be so accommodated to the habits, tastes, and feelings of the people, as to fit them at all points, like well-made harness. If they grow too enlightened we can double the window-tax; if they be disposed to kick, put on the breeching in the shape of an income-tax; if they go too much by the head, we can raise the price of malt, and, by way of a martingale, put a duty on spirits; if they jib, we can touch them on the raw with "the house duty;" if they step out too fast, tighten the "bearing rein" by 10 per cent. on the assessment; and should any attempt be made to bolt, we can secure them with a curb, by a tax on absentees.

[33] The perfection of taxation is to make it as much as possible like an insensible perspiration; or to cause it to subtract, like the vampire when lulling the victim to sleep, by fanning him with the wings of patriotism and the hum-hum of a liberal oration, on the principle of

"FORKING UP."

Multiplication teaches a short way of adding one number together any number of times. Its sign is a cat o'-nine-tails; its symbol a whipping-post. Since the wonderful powers of the number nine have been publicly discussed, we have had no more shooting at her Majesty, (Heaven preserve her!) which shows the transcendant powers of arithmetical argument. The Egyptian plague of frogs and flies exemplifies this rule. In Modern Rome we have multiplication of fleas. In Modern Babylon we have multiplication of bugs, particularly humbugs. In the West Indies we have [35] multiplication of musquitoes and piccaninies, and in the East, multiplication of oneself, as in the case of Abbas Mirza and his 1000 sons for a body guard.

Multiplication of Laws.—This is a favourite amusement with our modern legislators. It naturally leads to the multiplication of lawyers, whose proper calling is to set people together by the ears, for the multiplication of dissensions. The original type of this order was the plague of locusts.

Domestic Multiplication, or Multiplication of miseries. This rule is performed by taking unto oneself a wife for better or worse; then, multiplying as usual, and, at the end of fifteen or twenty years, having the young "olive branches" round about our tables.

Multiplication of Money.—This is the most universal case in the whole rule. The multipliers are the operatives, who are placed at the bottom, instead of the top of the arithmetical scale. They may be ranged, in general, as in the following:—[36]

These digits are to be worked from fourteen to sixteen hours a-day at the lowest possible fraction of pay. The product is to be set down in the 3½ per cents. or invested in the first unjust war in which this nation may be engaged; or the whole aggregate of sums may be multiplied by monopoly.[37]

LAWYER DIVIDING THE OYSTER.

Division teaches how to divide a number into two or more equal parts, as in the division of prize-money.

[39] Division is of great importance, whether political, ecclesiastical, commercial, civil, or social. Nothing is more likely to destroy your opponents than a split. Divide et impera is the true Machiavelian policy of all governments.

Numbers, that is the multitude, are to be divided, in a variety of ways,—by mob orators, or by mob-sneaks, or by parliamentary flounderers, or by mystifying pulpit demagogues.

The divisors should generally endeavour to work into their own hands, and the dividends may be compared to fleeced-sheep, plucked-geese, scraped sugar-casks, drained wine-bottles, and squeezed lemons.

Social Division.—The divisions here may be a tale-bearer, a gossip, or a go-between, and the divisors will "separate" to fight like Kilkenny cats, leaving nothing behind but two tails and a bit of flue. In a township, a volunteer corps is an excellent divisor: you may kill the adjutant by way of a quotient, on the surgical principle of "Mangling done here."

In the division of property by will, be your own lawyer, and your property will be divided to [40] your heart's content; for, as your heirs will most assuredly be divided amongst themselves, when they have done fighting over your coffin for what does not belong to them, they will call upon the Court of Chancery to divide it—principally among the lawyers, according to the lex non scripta.

In the division of profits, first take off the cream three times, and then divide the milk.

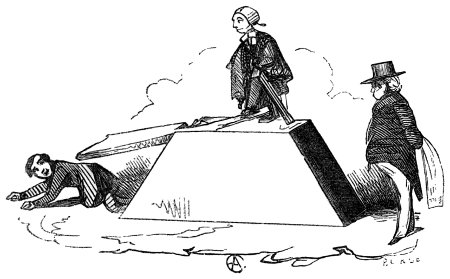

THE LION'S SHARE.

In all kinds of "Division of Money" endeavour to carry out the principle of the fable. Like the [41] lion when dividing the spoil, consider that you have a right to the first part, because you are a lion; to the second, because you are strong; to the third, because no one dares dispute your right; and to the fourth, because no one is so able as yourself to defend it. This is the lion's share.

Division of Time.—"Tempus fugit," and therefore the due systematic and proper division of time, in a rational manner, is the bounden duty of every "beardling." All philosophers and some kings, whether from Democritus to Tim Bobbin, or from Alfred the Great to that merry old soul, "Old King Cole," have divided their time equitably, according to the maxim of Horace, "Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero." Modern life teaches and exhibits the same necessity for the rigid division of the "stuff life is made of," and the twenty-four hours may be systematically divided, with great advantage, by young men, as follows:—

| HOURS. | |||

| 1. | To yawning, vertigo, head-ache and soda-water, say from one to three, A.M. | 2 | |

| 2. | From pulling off the night-cap to putting the first leg out of bed | 1 | |

| [42] 3. | To "cat-lap," "broiled chickens," Lackadaisical Magazine, "Dry Punch," and Gazette of Fashion | 2 | ½ |

| 4. | To the study of "cash stalking," the art of post-obits, with lessons from Professor Mœshes on the science of "Bondology." (Nocturnâ versate manu, versate diurnâ) | 1 | |

| 5. | To lounging, "dawdling," "muddling," sauntering, losing oneself in "ins and outs," "nowheres," &c. | 1 | ½ |

| 6. | To dressing for dinner, to getting on a pair of boots, half an hour, swearing at coat quarter of an hour, selecting vests half an hour, cursing pantaloons quarter of an hour, shaving, and other unnecessaries | 2 | ½ |

| 7. | To dining, wineing, brighting the eye, doubling the cape, getting half seas over, going into port instead of finding a champaign country | 2 | |

| 8. | To dressing for opera, "titivating," "bear's greasing," curling, barbarizing, scenting, putting on opera countenance, and ogling | 1 | ½ |

| 9. | To tying on stock half an hour, to putting on gloves quarter of an hour, to curling whiskers half an hour, to laying on the rouge, &c. | 1 | ½ |

| 10. | To bowing, scraping, hemming, hawing, yawning, toying, soft-sawdering, salooning, staggering, cigaring, coaching, and finishing | 3 | ½ |

| 11. | To no one knows what—Nisi castè saltem cautè | 5 | |

| 24 | |||

Long Division is so called when a long time is taken for the division of various sums, as in the case of the Deccan prize-money, or the Duke of York's debts. In these cases, various persons are [43] placed in the state of longing—hence the name of the rule, which is a figurative exemplification of "hope deferred."

Rule I—Teaches to work an expected legacy or an estate in reversion, or a right of entail, with a "post-obit bond," cent. per cent. on a stiff stamen.

Rule II—Teaches how to wait for a living instead of working for one. This is a hungry expectancy: yourself, in a consumption, with an interesting cough, preaching as curate to an admiring congregation principally composed of females, who bring jellies and jams, pitch-plasters, electuaries, and pills, "bosom friends," and other comforters, while the jolly incumbent, with his rosy gills and round paunch, writes you once a quarter to dine with him, to see how well he holds it.

Rule III. Chancery Long Division.—This is an exemplification of the "law's delay," and the rule is to be worked by giving the expectants the "benefit of a doubt," which is not quite so pleasant in Chancery as in criminal practice. The "Bidder" of this rule was John Lord Eldon.

[44] Rule IV.—Beside long annuities, there are also long dividends. For instance, in the case of Bamboozle, Humbug and Co. who lately declared the third and last dividend of three-fourths of a farthing in a pound, for the benefit of their creditors.

THE INSOLVENT TRAP.

"THE LAW BINDS, BUT THE LAW LOOSES."

Reduction is properly the "art of sinking." It teaches us, according to Martin, to bring numbers to a lower name without altering their value. When numbers are brought to a higher name, it is called Reduction ascending, when to a lower, Reduction descending.

Reduction ascending is to stand high in your own estimation, from the convincing reason, that, as no one thinks anything of you, you ought to think something of yourself. The visit of the Queen to Edinburgh raised the baillies so high in their own estimation, that it took them three hours to get up in a morning.

[46] Examples of Reduction ascending are to be found in the following cases:—When a noodle is made a lord; 2. When Timothy Fig obtains a baronetcy; 3. When Muggins keeps his "willa;" and when a beggar gets on horseback.

Reduction ascending for Females.—Mrs. General Swipes, Mrs. Colonel Trashee, Mrs. Major Minus, Mrs. Alderman Bumble, Mrs. Common-sergeant Sprigings, Mrs. Common-councilman Snigings, Mrs. Executioner Ketch, Mrs. Beadle Blow-em-up, Mrs. Corporal Casey.

Reduction ascending is to be seen in the manufacturing districts; when the body politic gets inflated, a "rising of the lights," that is, of the illuminati, may be expected. In these risings the scum always gets uppermost, and some political demagogue is ejected to parliament by a revolutionary eruction—to be reduced to his own level as a leveller.

Reduction descending.—

[47] This is the "old saw" Alderman Harmer used when he cut the city—or Lord John in his "finality" speech—cut his own fingers.

There have been many examples of Political Reduction both in our last and present ministry. The reduction of postage, so that it paid less than the cost, was an exceedingly business-like act. The reduction of cats'-meat in the storehouses at Plymouth, Woolwich, Portsmouth, and Chatham, from a penny to three farthings a-day, was also an example of legislative wisdom, and proved the maxim, "Sparus at the speketas letouat the bungholeas."

The reduction of paupers' food to "doubly diminutive and beautifully less" than that of the felon, is also "wisdom wonderful;" being a new way of offering a premium upon crime, at about thirty and a third per cent. It is presumed to have occurred with a view to the assistance of Old Bailey practice, and of the Poor Law [48] Commissioners, as it promotes Coroners' inquests and saves coffins.

Rule for the Reduction of Paupers.—Take "an operative," starve him in the streets till he becomes light enough to make a shuttlecock of, then place in his hands an order from an Edmonton magistrate, by way of a feather; bandy him about from parish to parish till you are tired of the game. Let him then fall into the lock-up of the station-house. Keep him sixteen hours in a cold cell without food. Bring him before the Board, put him on the refractory diet, water-gruel, poultice dumplings, and rat roastings. Keep him till he becomes so thin as to lose his shadow, then turn him into the streets to look for a job, with three yards of cord in his pocket, and a direction to the nearest lamp-post, as an intimation of what that job is to be.

A state may be reduced in the same way by nip-cheese patriots. Such "save-alls," when they lop off excrescences, bark the trunk—when they prune redundances, let loose the sap. These "flint-skinners" grind down professions, pare down dignities, sweat sovereigns, purge the [49] commonwealth, scour landlords, skin the army, starve the navy, scrape religion to the backbone, sell the honour of their country for a mess of porridge and its glory for a bag of moonshine; till at last John Bull becomes as lean as a country whipping-post, and would hang himself, only he has not weight enough on him to produce strangulation.

"BLOWED PUFFERY."

Proportion is sometimes called the "Rule of Three," because a certain system of conventionalisms has its origin in that, which is called, by way [51] of joke, the "Three Estates" of the realm—King, Lords, and Commons; in other words, a parliament, so called from its being the focus of palaver, in which originate those splendid specimens of collective wisdom, known by the name of Acts of Parliament—because they "won't act."

The theoretic proportion is, that numbers should be exactly balanced,—that one sovereign should equal six hundred lords, that six hundred lords should equal six hundred and fifty-eight commoners, and that these should represent twenty-nine millions of people. Now, as the interests of each of these estates are said in theory to be opposed to each other, and as they are all theoretically supposed to pull three opposite ways with equal force, it must follow that legislation would be at a stand still, by the first law of mechanics, viz. that action and reaction are always equal: but to prevent such a catastrophe of stagnation, and to set in motion this beautiful machine, a pivot-spring, in the shape of a prime minister, or prime mover, is superadded, and a golden supply, fly, or budget wheel, is introduced, by which the following subordinate, yet ruling principles are developed; [52] and thus we go on from age to age, making laws one day, and unmaking them the next, for the sake of variety.

"OUT OF PROPORTION."

It must not be forgotten that this rule is one of proportionals, as its name imports. It therefore teaches proportion in all its relations, social and political; it is the rule of our country, and seeks to develop that beautiful equality and justice, so conspicuous in all our institutions, exemplified in the following well-known legal and constitutional maxim, viz. "One man may steal a horse, but another must not look over the hedge."

It is a maxim of English law, that punishment should be proportionate to the offence, and have a relation to the moral turpitude of the offender. Hence the seducer and adulterer only inquire, "What's the damage?" By the same rule, it is held highly penal to sell the only ripe fruit in England, roasted apples; and the stock in trade of the basket woman is confiscated. She, too, is [54] sent to the Counter—because she is not rich enough to keep one with a shop attached.

CALLED TO ACCOUNT.

This brings us to the rationale of reward, and shows us the policy of making a prison superior to a poor-house. This wise arrangement of the collective wisdom of the Rule of Three (the three estates) is upon the principle of counter-irritation, that is, the best way to administer to the miserable is to inflict more misery, just as we put [55] a blister on one part to subdue inflammation on another, or set up a mercurial disease to cure a liver complaint. On the other hand, we cure villany by increased rations of beef, bread, beer, and potatoes, in accordance with the maxim, that "the nearest way to a man's heart is through his stomach."

On the same principle of "Proportion," the operative is to have for his share the pleasure of [56] doing the labour; for if one man had the labour and the gains too, it would be abominable, and destructive to all the usages of society.

It is also strictly proportional, that we should pay not only for what we have, but for that which we have not. Thus church-rates ought to be inflicted, not so much for the benefit of the church, but as the substitute for that wholesome discipline of flagellation, unhappily discontinued, and for the "good of the soul;" for if the spiritual benefit be great to those who pay for what they receive only, how great must be the reward of those who are content to pay for that which, they not only do not receive, but which they will not have at any price! Hence, it is possible that even dissenters may be saved—the trouble of spending their money in other ways.

The "Tax upon Incomes" affords also a striking example of the doctrine of Proportionals. It is so beautifully equalized, that the loss upon one branch of trade is not to be set off against the gain of another, the object of the act being, no doubt, to put a stop to trade altogether, as the best means of placing things statu quo, the grand desideratum of modern legislation.

[57] "Bear ye each other's burdens" is a sublime maxim. The principle of the lever is well brought to bear in the doctrine of proportionals—and shows how to shift the weight of taxation from the shoulders of the rich upon those of the poor—

A SLIDING SCALE.

The laws and regulations for the conduct of our civil polity and social condition being founded on these divine principles, it is assumed as a fundamental maxim, that "great folks will be biggest," and he who has not learned that this is the ideal of [58] true proportion, and who does not recognise it in his practical philosophy, will be compelled to knock his head against a wall to the day of his dissolution.

"BROKEN DOWN."

The word Fractions is from the Latin "Fractus," broken. A Fraction is therefore a part or broken piece. A broken head is a fraction; a broken heart is a fraction; a bankrupt is a fraction—he is [60] broken up; yet a horse is not a fraction, although he may be broken in—but his rider may have a broken neck, which is called an irreducible fraction. Speaking generally, therefore, a fraction may be considered as a "Tarnation Smashification."

FRACTIONAL SIGNS.

Fractions are of two kinds, Vulgar and Decimal. Vulgar fractions are used for common purposes, and examples may be seen in the plebeian part of our commonalty, such as coal-heavers, costermongers, sheriff's-officers, bailiffs, bagmen, cabmen, excisemen, lord-mayors, lady-mayoresses, carpet-knights and auctioneers.[61]

Vulgar fractions may be known by the way in which they express themselves. They are more expressive than decimals; and the words, Go it, Jerry—Jim along Josey—What are you at?—What are you arter?—Variety—Don't you wish you may get it?—All round my hat—Over the left—All right, and no mistake—Flare up, my covies—I should think so—with those inexpressible expletives which add so much to the force and elegance of our language, may be taken as specimens of Fractions.

"AN ANCIENT AND MODERN MUG."

KNOCKING DOWN THE LOT.

DONE BY INTEREST.

To think of getting on in this world without Interest, is ridiculous. Place and Promotion are not for Fitness or Worthiness, but to serve particular Interests, private or public; and yet a [73] number of very simple persons, who have as large a green streak in them as a sage cheese, without its sageness, are continually wondering that virtue and talent do not get all the "good things" of a vicious community. Punch forbid! Is not virtue declared to be its own reward? and as to talent,—let a man be content with that. It is a positive monopoly to covet wit and money too.

AT A PREMIUM AND DISCOUNT.

To take care of our Interest is the great law of Nature, and is universally followed. Every one for himself, and Fate for us all, as the donkey said when he danced among the chickens, is as profound a maxim as the gnothi seauton of Plato. [74] "Take care of yourself" is of more importance than "Know thyself." To take care of oneself is a science which comes home to every man's business and bosom. It is "wisdom" identified with our personal character. It is philosophy turned to account. It is morality above par. It is a religion in which "every man may be his own parson," find his Bible in his ledger, his Creed in the "stock-list," his Psalter in the tariff, his Book of Common Prayer in the railway and canal shares, his Temple in the Royal Exchange, his Altar in his counter, and his God in his money.

THE OLD AND NEW PRINCIPLE—BOTH WITH CREDIT.

[75] Principle, or Principal, is an old term used by our forefathers in "money matters" and commercial transactions, but is now obsolete. It formerly represented capital, and raised the British merchant in the scale of nations; but it is now a maxim of trade to discard Principle as not being consistent with Interest. It is paradoxically Capital to take care of our Interest, but it seldom requires any Principle to do so.

"The want of money is the root of all evil." Such is the new reading, according to the translation of a new sect called the Tinites. In the orthodox translation, the love of money was unfortunately rendered. To be without money is worse than being without brains—for this reason we should oppose all dangerous innovations, which in any way have a tendency to disturb the "balance of Capital." Right is not to usurp might. We are not, for the sake of Quixotic experiment, to invade the interests of the landed proprietor by an Anti-Corn Law movement, nor the vested right of doing wrong, which the various close corporations of law, physic, and trade, &c. have so long maintained, making England the envy of the world and the glory of surrounding nations.

THE TIN-DER PASSION.

Interest, therefore, teaches us to interest ourselves for our own interests, and to keep them continually in view in all our transactions. When a man loses sight of his own interests he is morally blind; he must, therefore, according to this rule, walk with his eyes open, and be wide awake to every move—keep the weather-eye open, and not have one eye up the chimney and the other in [77] the pot, but both stedfastly fixed on the main chance.

Interest teaches us also to swear to anything and admit nothing; to prove, by the devil's rhetoric, that black is white and white black; to tamper, to shuffle, to misrepresent, to falsify, to scheme, to undervalue, to entangle, to evade, to delay, to humbug, and to cheat in virtue of the monied interest.

FAITH AND DUTY.

In the days of our forefathers, we had a most excellent compendium of Faith and Duty, called [78] the "Church Catechism," which taught us not only to "fear God and honour the King," but to be "true and just in all our dealings." The "fast and loose," "free and easy" system of "liberality," shuts the Creed and the Catechism out of half our schools; and worldliness teaches in its place the creed of Mammon. Instead of being taught to worship God, we are taught to worship money. Instead of honouring the Queen, we are told to bow down to the "golden image" which trade has set up; we no longer consult our conscience, but our pocket; for principle we read interest—for piety, pelf.

In illustration of this, the following "cut and dry" "'Change Catechism," which fell from the pocket of a Latitudinarian bill-broker, is subjoined, as affording the best examples of the Rule of Interest.

When goods are bought or work is done, a bill is to be made out and delivered. In some cases the bill may be made out before the work is done, [84] and work charged in prospective; and therefore the making out of bills is an art and mystery known only to the professional man or the tradesman. It comprehends the mystery of mystification, and impudence and assurance are its two first rules. The milkman is not only allowed by parliament to water his milk, but to cut a notch in his chalk and mark double. The baker thinks it legitimate, and part of his vested rights, to put in "dead uns;" the butcher to "hang on Jemmy;" but the birds noted for the longest bills are the carpenter woodpecker, (who undertakes to take you under) the gallipot [85] crane, the red-tape snipe, and the heron. The bills of each of these bipeds are as long as from this to the paying of the National Debt, and as unfathomable as the Bay of Biscay—or the lowest pit of——

L

A DECIMAL FIGURE.

Decimal Fractions are so called because the fractions are always tenths. They differ from [90] Vulgar Fractions in this, that the denominator is not written, but a point before it is used instead.

A STRONG TITHE.

Decimals are best illustrated by tithes, which are general and universal tenths extracted in every part of "merry England." They are added, subtracted, multiplied, and divided like any other numbers, but to designate their value a point is prefixed.

In tithes, as in decimals, the denominator does not appear; that is to say, the incumbent rarely lives at his incumbency. When tithes are to be added, taken, or subtracted, the tithodecimo point [91] is used as his representative, namely, the POINT OF THE BAYONET.

To make a point of "doing good by stealth" is a national virtue; and among all other "points" in this uncertain world, the "point blank" is the most certain. This may be made with a rifle, [92] when the pockets are to be rifled, either with or without a bayonet at the end of it. The charge for spiritual care is best settled by a charge of dragoons; and a discharge of clerical arrears by a discharge of fire-arms.[4]

Take a tithe-owner, a collector, a proctor's warrant, and a constable, and go in a body to the house of a Quaker, or the mud hovel of an Irish Catholic. Enter the house by means of a crow-bar. Take pigs, poultry, pots, pans, sticks, or rattletraps. Obtain an appraiser, call in a broker, and divide the spoil by means of any number of vulgar fractions, called purchasers. Take the dividend, called plunder, and "pocket."

The proper value of a decimal is only to be ascertained by his points of character, and they are to be found of full value in many parts of the kingdom, in the shape of worthy curates, and honest rectors and vicars, dividing not their flocks, or the produce of their flocks, but their own time, means, and money, in the conscientious discharge of their clerical duties.

The Rule of Practice is indispensable in all our operations. It is in some degree the "ultimatum" of the preceding rules, for as the proverb says, "Practice makes perfect."

Nature is said to have begun the creation of "living infinities" by this rule, for in the words of the poet,

Practice is thus divided into two kinds—the first called Practice Preliminary; the second is denominated Practice in General.

[95] Practice Preliminary is experimental philosophy, or asking discount for a bill at 18 months; Practice in General taking in the flats. The one resolves itself into "trying it on," the other to "clapping it on."

"Trying it on" is an universal principle, from the old Jew salesman who asks four pounds for a thread-bare coat and takes four shillings; or the old cabbage woman who offers 3lbs. of "taters" for two pence and sells 7lbs. for three farthings; to the prime minister who asks three millions of taxes, and expects five. The converse of this rule is, "Don't you wish you may get it."

Practice is performed by taking "aliquot parts;" to be a man of some "parts" is therefore necessary. The application of our "parts" to the science of L.S.D. with a view to their development and perfection, is the aim of the rule, and the "practice of Practice" is to show,

PRACTISING AT EXETER HALL.

HULLA, BOYS, HULLA.

Practising for the Army.—As shooting and slaying are the legitimate objects of this profession, [100] you cannot begin too early. The first instrument to be used is a pea-shooter; this is for the age P.C. previous to corderoys. The second is a pop-gun, indicating the age of breeches (and breaches). From this we arise to "sparrow-shooting," after the ruse de guerre of the salt-box has been tried without effect. Being now grown bloody-minded, we go to that sanguiniferous-looking house at Battersea, called the Red House, (being of a blood colour, from the enormous slaughter committed near it,) and here we take lessons in pigeon-shooting. From hence to the Shooting Gallery, Pall Mall, we improve rapidly. A lieutenancy in the Guards is our next step. To this succeeds a dispute respecting the glottis of Mademoiselle Catasquallee, and "Chalk-Farm" or "Wimbledon Common" is the result; and here, unless courage should ooze out of our fingers' ends, we may stop; our courage is apparent, and for the future we may shoot with the "long-bow" to all eternity without fear of contradiction.

Practising for the Profession.—"Cutting up" and "Cut and come again," are the maxims of the surgeon; and as no trade or profession can live [101] except by the adoption of the "cutting system," and if a man cannot cut a figure, he will assuredly be cut by his acquaintance, surely the art should be thoroughly studied. As a preliminary step, Burking and body-snatching must be mastered; and then you may go snacks in a "subject," and take your "loin of pauper," "leg of pauper," or "shoulder of beggar," or "rump of beggar," or "sirloin of alderman," or "fore-quarter of citizen," or "hand and spring" of beadle or bellman. Or should your taste be fastidious, you may take a "fillet of cherrybum;" or club for a "sucking-kid." On these practise till you are perfect; and should it so happen that any of the personages above-named should turn out to be related by consanguinity, be as stoical as a reviewer, and make no bones of cutting-up (if necessary for science) your own father.

Practising for the Ministry.—The aspirant for the "tub," "born in a garret, in a kitchen bred," commences his spiritual career by announcing to the elect that he is almost sure that he has had a call (caul), for he has heard his mother say he was born with one. He may next exhibit [102] his buffetings with Satan by showing the marks of the beast, in the shape of double-dealing, pettifogging, shuffling, cutting and cheating; he may next venture on the new birth.

He now attempts open-air preaching on Kennington Common, and exhibits spiritual rabidity in good earnest. He foams at the mouth, barks and bites, and yells in his ravings; calls himself from a pig to a dog, and from a dog to no gentleman. What is he? "A bundle of filthy rags," "a whited sepulchre," "a cancerous sore," a "sink [103] of pollution," "a mass of corruption," "a cesspool," "a common sewer," "a worm," "a scorpion," "a snake," "a spider," "an adder." He may also charge himself with murder, abomination, witchcraft, lying, and every vice denounced in the Decalogue, on the principle of "the greater the sinner the greater the saint."

Having thus initiated himself into the spiritual fraternity, he may write a work to prove that the "Church damns more souls than she saves."[6] He then mounts the rostrum as a burning and a shining light. He deals in brimstone, wholesale, retail, and for exportation. Now he unites his spiritual with secular power, and mixes parliamentary logic with divinity, electioneering squibs with "Hymns of the Chosen;" makes Lucifer cuckold, and swears himself his true liege man on the cross-buttock of a radical candidate. He now receives the degree of D.D. from a Scotch university, for 7l. 13s. 6d., and begins to feel as "big as bull-beef;" his lank hair curls; he has red velvet cushions to his tub; he begowns and belappets [104] himself; he looks on all sides for an half-idiot heiress, or infatuated widow in a state of fatuity, and marries. Thus he jumps into his bishopric, makes religion a "good spec," till it is found out he has had "two wives" before, and a variety of miniature portraits of himself:—and thus ends his Practice.

PRACTISING FOR THE OPERA.

Man is a "forgiving animal," and this is a better definition of him than Plato's "biped without feathers," which the plucked cock demonstrated. Man is the only animal which strikes a bargain. A dog does not exchange a bone with another dog; and however skilful he may be at a steak, he is not at all clever at this sort of "chop."

"Our chops are our masters," says Hobbes; and it is all "a matter of wittles," says Sam Weller. Hence arise the art and mystery of swapping, buying, and selling, and the notion of trade and commerce.

England is per se a nation of shopkeepers—we do every thing upon the principle of small profits and quick returns. To barter the national honour [106] is legitimate policy; to sell up our enemies has been a practice since the days of the Plantagenets.

Hence we can always buy our enemies, if we cannot beat them. Buonaparte, according to the radicals, was sold at Waterloo; we have been recently sold to the Russians; and thus British gold has been always more powerful than British steel.

Ten thousand thanks will be given to any influential gentleman who will procure the advertiser a place of commensurate value under government: an under lord of the treasury, a commissioner of excise, a distributor of stamps, a head clerkship, or any other situation, in which the principal duties are to receive the salary.

[107] Appointments in the army secured without risk, loss, or trouble to the purchaser. Cornetcies, Ensigncies, Lieutenancies, Colonelcies, to be disposed of, at the lowest possible prices. Also a few cast-off ribbons, stars, spurs, and garters, to be had a bargain.

The next presentation to a valuable rectory, to be had for a song. A title for orders, "cheap as dirt." Degrees may be obtained of A.M., LL.D., D.C.L. and D.D., on reasonable terms; and livings wholesale, retail, and for exportation. Apply at the "Bottle-nose Head," York; or at the "Frigasseed surplice," Canterbury.

[108] Comfortable and respectable sittings at Beelzebub Chapel, Brimstone Alley, St. Luke's, under an able minister, by the quarter, month, or year. Pews to hold eight, 2l. 12s. 6d. per annum; single sittings, 10s. The Pewseyites will have the right of election and other privileges.—N.B. No connexion with the parish church next door.

To be sold, peremptorily, the property of a gentleman about to travel, (once a rum cove, now a Sidney cove,) a five-year old hunter, the most splendid horse in Europe, with grand action. Got by Spavin out of Roarer, grandsire Glanders, grandam Botts, warranted sound and without fault; (blemishes are not faults, but misfortunes;) gentle to ride, quiet to drive, warranted to do fourteen stone, or any other weight. Price 120 guineas.—No abatement.

[109] Sale by auction, in Smithfield. Without reserve. A most eligible and desirable lot. Coming in low. Parasol, bustle, and baggage included. My better half. Weight, sixteen stone. Has taken the lead at All Max. Temper, mild (horse-radish). Eloquence, Broughamatic. Voice, Saffernhillish. Person, Nixmydollyish. Talons, cataclawdish.—No abatement.

The idea of trade and commerce naturally leads us to the consideration of the sublime science of Political Economy, which endeavours to dogmatize that profound conundrum, that the natural rate of wages is that which barely affords the labourer the means of subsistence, and of continuing the race of labourers—meaning thereby, the starvation point at which a labourer can be worked. It is assumed that the labourer has so much work in him, and the problem is to draw it out at the least possible cost—of whip or legal enactment—or police forces or military expenditure.

Another leading doctrine of the political economists is, the fatal necessity of starvation. It is maintained, and that seriously, that "God, when he made man, intended that he should be starved;" that human fecundity tends to get the start of the [110] means of subsistence; that the former moves as 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64; but the latter only as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. The consequence drawn from this proposition is, that poor-laws, or any efforts of charity, are only a childish indulgence of feeling; for since there will be a surplus number, who must at all events be starved, if the life of one is saved by charity, whether public or private, it is only that another may be starved in its stead. Hence the perishing of annual multitudes may be looked upon as a proof of the national wealth; and the poor-law system, and the Queen's Letter, but so much concern utterly useless; and the only remedy for our abundant population is for us to return to the system of the ancients, and legalize a few Herods, or, to go further back, to make every man a Saturn—the eater of his own children.

Discount is the allowance made to a person, for paying money before it is due; so says Walkinghame; but there are now few persons who commit so egregious a folly, the plan being not to pay until it has been due a long time, and then get discount as for ready money.

The usual manner of settling accounts in the City is to purchase for ready money; to give a bill at three months, which is to be considered as equal to ready money; and when the bill becomes due to give—the cash? No! but another bill at five months. This is called cash payments.

[112] Leaving the City, as being "vulgar," let us look at discount by the broad light of Universality. Discount means something "taken off," or reduced by so much, or decreased in value, or lessened.

"DISCOUNTING FOR A MAN FORMERLY."

A man is said to be at a discount on 'Change, when he has no change at the Bank; when he has no banker in the City; when "no effects" is written on his "mandible:"—at Almack's, when he ceases to invite dinner eaters; among the ladies, when grey hairs and crows' feet make their appearance, and teeth their disappearance.

[113] Par, above par, below par. We are at par, when in that blessed state of equanimity found in perfection at a Quakers' meeting; above par, when floundering about in champagne; and below par, when cooling down on water gruel and Seidlitz.

Examples of discount at the present moment are too numerous to mention. Every thing seems at a discount; radicals, dissenters, theatricals, fine arts, scientificks, trade, commerce, manufactures. Asses' heads alone are looking up.

Involution and Evolution are two rules of arithmetic which signify getting in and getting out. Involution signifies such matters as getting in love, getting into a lawsuit, or getting into debt. It is the rule of entanglement, and is represented by a fly in a spider's web.

Evolution comprehends all the tricks, shifts, schemes, and stratagems, by which we get out of our various difficulties; but it may be observed that it is much easier to become involved in any matter, than to get disentangled: whatever may be our evolutions, it is a difficult matter to get out of love, out of a law-suit, or out of debt.

The ways of getting into debt are multiform. To be involved is patriotic, fashionable, genteel, and sentimental. To pay is vulgar, inconvenient, and unpopular. [117] The man who lives within his means is never considered to have any means. A man in debt possesses an interest and an importance truly pleasurable. It is surely something to know that in your little self a hundred are subject to hopes, fears, anxieties, speculations, aspirations, and a world of such like poetry. The greater the number of creditors, the greater must be the sensation produced; and the production of a sensation is every thing in fashionable society.

The old proverb was, "Out of debt out of danger;" but modern arithmetic teaches, "In debt out of danger;" the law of debtor and creditor being fashioned according to this maxim, which is now the Lex Scripta of the courts. To be over head and ears in debt, is the best security; "debt is the safest helmet." To be not worth powder and shot, or to make believe you are not, is the best method of keeping on the wing. It requires, however, some curious evolutions to enable an empty sack to stand upright.

This is an involuntary process, and an entanglement equally powerful with the meshes of [118] the law. In this case, however, the pleasure increases with the entanglement, as the fly said in the honey-pot. The arms of a fair lady are the softest bonds; the poison of a maiden's lip the sweetest poison. To be in love is to be entangled in a cobweb of ten thousand ecstasies, where every string is bliss, and every mesh is beauty. In this web, Cupid sits as an angel in one corner, and Hymen on the other; thus bound with sighs, tied with kisses, linked by embraces, chained by tears, lovers disport themselves; till Hymen, in fear that they should die of ecstasy, tightens the web, and binds them hand and foot in the true lover's knot of matrimony.

| Rule 1. | Make up your mind to "go the whole hog" with your party. |

| 2. | Flatter, gammon, and gloze all parties. |

| 3. | Humbug your opponents, and cheat your supporters. |

| 4. | Make love to every prevailing vagary of the day, and coquet with Mother Church, and her fantastical daughter, Miss Dissent. |

| [119]5. | Promise every thing, perform nothing, and be the last year of your parliamentary term a contradiction of the six preceding years, so as to ensure another return. |

Supposing yourself to be a green yokel, just raw from school, with little wit, little money, and little influence, act as follows:—

1. Marry for the sake of respectability and a little more money.

2. Give away soup to the poor, flannel petticoats, trusses, and baby linen.

3. Set up schools on the free system, "every boy his own archbishop:" Free-trade in religion, and no walloping.

4. Get into a squabble with your Rector, about free grace and non-election.

5. Write once a week in the dissenters' "slop pail," against clerical intolerance, tithe pigs, "red noses," round paunches, lawn sleeves.[120]

6. Attend the jawy jobations of Exeter hall, as a "flowery speaker," and advocate various Jew, Gipsy, Voluntary Church, Anti-pseudo-baptistical Societies, till you are black in the face.

7. Join the Society for the Diffusion of Useless Knowledge, the Donkey Protecting Society, and other congenial "Institutes."

8. Build a chapel, and bribe a congregation to come to it. Become a teetotaller; be a betwixt and betweenish, half-and-half, out-and-out radical. Defeat the imposition of a Church rate—rave against the taxes—pledge yourself to support triangular parliaments, universal suffering—blindfold voting—and confusion to all order.

MEASURING BY THE "YARD"—TRUE FIT.

Duodecimals teach us to find the superficial contents of any "thing." A thing is properly [123] something, neither woman nor man; possessing all the superficial of either, and the substantials of neither: such as numbsculls, lordlings, quacks, empirics, &c.

Duodecimals also teach the mensuration of plastering, painting and glazing; which comprehend the arts of palaver and gammon, and the science of Flattery in general.

This is, above all others, a "superficial age," and the mensuration of superficies is characteristic of the modern era—the age of meretricious flummery. Our science is superficial thinking; our morality, superficial blinking. Every thing is made now-a-days for the "surface," which, like the gilded wooden organ pipes, placed in front of that instrument, are not made to blow, but for the sake of show. In learning, we get a smattering instead of the real thing; and we drop the meat for the sake of the shadow. The deep and the solid have long ago been discarded: in short, this is the age of gammon, and society is like a quire of "outsides foolscap."

Of Flat Surfaces.—A plane or flat surface has length and breadth without thickness. Flat [124] surfaces are often made, by some peculiar property of polarized light, to reflect rays which do not belong to them. Thus, flats pass for solids, and "shallows" for "deep-uns."

Book-keeping is not to be understood only as the art of "Book-borrowing," a very good science in its way, but as the highest branch of the science of legerdemain, invented for the express purpose of enabling the speculative to conceal their accounts, just as the use of speech is given to man to enable him to conceal his thoughts.

We have excellent directions given us on this head from very high authority, which is to be understood according to the Benthamite Philosophy. "How much owest thou my lord? And he said, A hundred measures of oil. Take thy bill, and sit down quickly, and write fifty." Hence the children of the philosophers are wiser than the children of light.

In "keeping books" it is not only indispensable that you should keep them, but that they also should "keep you." This is in accordance with [126] the free-trade reciprocity system; and to enable them to do it requires but little tact. For instance, you open a shop—not for the purpose of doing business, but for doing some unfortunate flat, in the very spirit of a "Good-will;" so that when your business is done, your client may find his business done too, and when you have taken yourself off, he may find himself taken in. This example may be repeated any number of times.

Upon entering life, every young man must consider that it will be quite impossible to live without some "cash in hand;"—that he will, at times, be inevitably called upon to "fork out," "dub up," or "come down;"—and that in all transactions, such as swelling and dashing, cutting and flashing, it will be necessary to keep a sharp look-out upon the "blunt," tin, or pewter, as it is variously termed; if not for your own satisfaction, at least for your beloved father's, whom you are in duty bound to bamboozle. There are certain items which never need come into this account; namely, board, lodging, tailor's bills, boots, shoes, linen, horses, and such like necessaries; these belong religiously to the old boy, or are fit and proper matters for "whitewashing."

[127] To fulfil this purpose, open a cash account, putting Dr. in the left hand corner, which signifies Dear Father, in honour of your respected parent, or in testimony that everything is dear; and Cr. on the right hand, which may signify "cruel little I have to spend." This is called the Waste Book. The items introduced are merely hints for the getting and disbursement of Cash.

| Simon Sapscull Clutchings, in Account with his Father, from May 1 To May 3. | |||||||

| Dr. | Cr. | ||||||

| £ | s. | d. | £ | s. | d. | ||

| May 1. | May 1. | ||||||

| Out of the old chap, by wheedling and bullying | 50 | 0 | 0 | Paid at Shooting Gallery, and at the Fives' Court | 4 | 16 | 0 |

| Out of the schoolmaster, after being in Whitecross-street two hours | 0 | 3 | 8 | For cigars, riding whip, Sporting Calendar, and Life in London | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Out of mother, by way of bonus on "good nature." | 10 | 0 | 0 | For salve for the dog's tail, (burnt some time since) | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| [130]Out of father, for charitable purposes | 20 | 0 | 0 | Spent at Divan, Coal Hole, and at various places on stroll | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Out of sister, to lend a friend in distress | 20 | 0 | 0 | For Covent Garden Oyster Rooms, cigars, brandy, champagne, and various other matters indistinctly remembered | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Out of mother, another 20l.—having lost the first when carried home drowned, (good idea this,) Mem. to be repeated. | 20 | 0 | 0 | Relief to a poor young widow, soda water, and restorative cordial to the dog | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Paid Duncombe for books, according to father's direction; Flash Lexicon, ditto Songster, ditto Anecdotes, ditto Morality, ditto Divinity | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| May 2. | [131]May 2. | ||||||

| Out of father, for divinity books, (sorry didn't get more, as the old chap is so pleased to think I am "preserved") | 40 | 0 | 0 | Paid at Westminster pit, and loss on dog Billy | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Cigars and coachman, for a turn with the ribbands | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Turn out in post, breaking horses' knees, paid horsekeeper | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Cigars, sandwich, heavy wet, negus, brandy, brandy-and-water, Welsh-rabbit, port, sherry, waiters | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| At the Lowther—gloves, pumps, supper, bursting waiter's tights, breaking glasses, negus, wine, supper, brandy, soda water, brandy, wine, whisky, brandy, claret | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Tearing ladies' dress, spoiling gentleman's watch, damaging ladies' false teeth, smashing fiddle, &c. | 26 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| To a destitute mantua-maker | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Worm pills for the dog | 1 | 10 | 0 | ||||

| [132]May 3. | May 3. | ||||||

| Out of mother, to invest on the sly in the 3½ per cents. for herself | 40 | 0 | 0 | To soda water and brandy, brandy solus, Seidlitz, vinegar and water, cab to Park, ditto to Colonnade | 1 | 15 | 0 |

| Borrowed of Jem | 3 | 0 | 0 | [133]To rouge et noir, bagatelle, breaking cue, and losses on learning French and Hebrew | 50 | 10 | 9 |

| Balance due to me | 56 | 3 | 0 | To "Drury"—cigars, saloon, cab, brandy, Falstaff Drawing Room, music, oysters, champagne, brandy, damaging lady's bonnet, ditto gentleman's glass eye, ditto whiskers, ditto lady's curls, ditto curtains, ditto windows, ditto policeman's nose | 76 | 14 | 10 |

| Relief to a poor servant girl out of place | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| To Mrs. H. for her motherly care for next three days | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| To the pew-opener at church on Sunday | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| £259 | 6 | 8 | £259 | 6 | 8 | ||

[134] Having been thus initiated in the making out of personal accounts, the pupil must now turn his attention to the methods of Book-keeping adopted by "gentlemen in difficulties," connected with that peculiar process of law which professes to put new wind into a collapsed bladder, and enable an empty sack to stand upright. The example is called taking the "Benefit;" the principal part of which is making out a Schedule, which may be done as follows:—

| £ | s. | d. | ||

| Paid for | twinkling a bed-post | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Spouting the tea-kettle | 1 | 15 | 0 | |

| New teething the hair comb | 1 | 10 | 0 | |

| Stopping holes in cullender | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| Pulling the gray hairs from hearth broom | 0 | 15 | 0 | |

| Whitewashing inside of chimney | 1 | 15 | 0 | |

| A Newgate-Calendar-novel, to soften hard-hearted cabbages before boiling | 1 | 11 | 6 | |

| [135] | Pectoral lozenges for short-winded bellows | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| 1000 cigars, to smoke for cure of corns | 12 | 10 | 0 | |

| Pigeons'-milk on the 1st of April | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| A leather saw | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| A worsted hatchet | 0 | 10 | 0 | |

| New vamping and welting India-rubber conscience | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Loan to Thimble-Rig, Esq. | 15 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ditto to Billy Blackleg | 20 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ditto to Richard Roe | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ditto to John Doe | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ditto to Jack Noakes | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ditto to Tom Styles[7] | 60 | 0 | 0 | |

| £204 | 10 | 6 | ||

Notwithstanding the copious examples above given, there is one other kind of Book-keeping which can only be thoroughly understood by the first accountants, and is only practised by the first of practitioners. This is making up a book for the St. Leger, which is

LEGERDEMAIN COMPLETE.

| [136]An Account of the Expenditure of the "Secret Service Money," from 1825 to 1841. | |||||

| £ | s. | d. | |||

| Paid | to Colonel Queerum, for a series of Tricknometrical admeasurements of the length and breadth of public credulity | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | |

| To Captain Audacity, for endeavouring to determine the "heights" of "impudence" in Whig Radicalism | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Colonel Feel-your-way, for surveying the Terra Incognita of ways and means, per session | 1,500 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Dr. Sapscull, for instructions in sapping and mining the constitution | 2,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Dr. Gammon, for moonlight lessons in the art of Mystification and Jack-o'-Lanternism | 500 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Dr. Lardner, for horizontal sections of the broadest latitude of latitudinarian policy | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Lord Bumfiddle, for a series of impracticable experiments in the House of Lords | 5,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| [137]To Lord Bumfiddle, for his project to light both houses with "cats' eyes," to facilitate legislation in the dark | 2,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To expenses of a tour to the Devil's Ace-à-Peak, to discover the polarity of political consistency | 3,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Dr. Bubblejock, for a new plan of making long speeches out of soap bubbles | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Jack Pudding, for the sale of nostrums, "pitch plasters," and hocusses | 2,500 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Döbler, for instructions in legerdemain, sleight of hand, and hocus pocus | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To J. H. for his chemical extraction of the blunderful from the public accounts | 1,500 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To a cargo of soap and soft sawder, to unite the dissenters | 500 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To various sops thrown to the Irish hound "Cerberus," on going into the Tartarus of a new session | 17,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Mesmerizing a Whig Lord, at stated intervals, and for dust to throw into the eyes of the Church | 3,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Oliver Hill, for his plan of buying and selling, and living by the loss | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| [138]To Pawnbroker's interest on pawning the crown and keeping the Queen in check | 5,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To pepper, mustard, Congreve rockets, and Spanish flies, for seasoning speeches at public meetings | 2,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To 150 yards of new spouting for Exeter Hall, and for the repair of weathercocks at St. Stephen's | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| For putting a new bottom to the fundamental maxims of English law, (paid by Sheriffs) | 5,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To a constant supply of "hot water" for both Houses, and for the use of "cold water" to throw on petitions | 5,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Dr. Shuttlecock Casey, for his plan of "water grueling" the poor, and "blowing up" schoolmasters with "small beer" science | 0 | 0 | 0 | ¼ | |

| To "Hogs' Wittles," of various kinds, in the shape of pamphlets, addressed to the swinish multitude | 3,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Daniel O'Connell, for pulling the wires of the political Punch and Judy, seven sessions | 150,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| [139]To Scott the diver, for going to the bottom of the Exchequer bills affair, and reporting unsound | 1,000 | 0 | 0 | ||

| To Colonel Common Sense, for blowing up the wreck of the "Impracticable," and reporting "safe anchorage" (unpaid) | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| £215,600 | 0 | 0 | ¼ | ||

CHARLES I.—A BLOCK-HEAD.

We have already treated on "superficial measurement;" we now come to "Solid Measure." Solids are, in general, what are termed "blockheads," [141] or "thickheads," or "bumbleheads," or "numbsculls," exemplified in "senior wranglers," "tripos," "professors of Greek," and teachers of Latin. The advantages of a thick scull are great. It was found upon the gauging of Porson's head, by the heads of his college, that his scull was so thick that it became the subject of marvel how knowledge could get in—once in, it was held impossible to get out. The case is the same with most of our schoolmen.

Solid Measure has been applied with great success to the measure of blockheads by Messrs. Gull and Spuzzy, Epps, Ham and Co. The measure is now principally performed by a Scotch "Combe," consisting of four "bushel-heads" in one. This instrument, the length and breadth and thickness of a head being given, will work out the solid contents and capacity of the understanding, to the fraction of a fraction.

The science so formed upon the measure of wooden heads was invented by Albertus Magnus, who flourished in the thirteenth century and made a wooden man with a wooden head, dividing it into [142] sixty-eight orders or ratios. Gull and Spuzzy, however, finding this large number bother them, took away thirty-three, sans cérémonie, observing, "Organum botheratio sive ambarum rationum mistura fortuita effervescens, bullas gignens." But the whole scull is now mapped out into thirty-six compartments, and subjected to a trigonometrical survey, and a barometrical admeasurement of comparative heights and hollows.

These divisions are so delightfully situated, that from Combativeness, the organ of fighting, we enter Friendship, (Adhesiveness,) without a turnpike between. Acquisitiveness, the love of money, is next-door neighbour to Ideality, the quality of poets, who generally show so much contempt for it. Constructiveness, the organ of building, lies as a foundation for that of Music, and handy for the grating of saws, the knocking of hammers, and the squeaking of wheelbarrows, as accompaniments to Haydn's symphonies. Metaphysics are also handy for wit. Ideality is a parallelopiped, Hope is a square, Cautiousness a circle, Eventuality a semicircle; then we have cones, rhomboids, trapeziums, polygons, hexagons, decagons; [143] while Language, like the science itself, is all my eye.[8]

Thick-heads, block-heads, bumble-heads, or basket-heads, which used in former days to be symbols of obesity, and gave rise to the maxim, "Great head, little wit," are now the indications of intellectual superiority. "The bigger the head the greater the genius," as the mushroom said to the cucumber; and to have a head as big as a baker's basket, or the bustle of a lady mayoress, is perfection.

To fumble these heads is the business of the Feelosophers; so called from feel, to fumble, os, a bone, and pher, far from the truth. This science being at our fingers' ends, a great advantage is felt in all the transactions of life, as the most tender ideas maybe expressed with mathematical certainty, numerically, figuratively, and arithmetically, as follows:—

Divine Louisa,

I need not remind you that last night I felt (not emotions, raptures, and soul-thrilling transports) but your BUMPS. On returning home I also felt my own, and I hasten to inform you that while 17 is throbbing like an earthquake, all my 33 is insufficient to describe my state, on finding that a kind Providence has ordained that for every bump on your beloved head, there rises a corresponding bump on mine. I 18 you do not see them, and in 16 declare that my No. 11 only centres in you.

I do not wish to give a false 26 to what I say, but in the 30 of your becoming mine, my No. 1 will develop No. 2, and all my No. 3 will be directed to 14 for your 13. Dearest girl, need I say more? Nos. 2, 3, 4, are so harmoniously protuberant in both of us, that I can have no doubt of either a large or a happy home. Your 23 and 24, and the 26 on your [145] cheeks, are indeed divine. Sweet soul, do allow your 13 to name as soon as possible your 31 and 27, that no untoward 30's may cross our 17's.

Yours, from 1 to 36,

Bobby Bumpas.

"ASSURANCE."

Assurance or Brass is a rule of the utmost consequence in all monetary transactions; by it miracles have been performed from the earliest ages. A good stock of assurance, i. e. impudence, [147] will carry a man further than even a stock of money, wit, or learning. The brazen head of Friar Bacon, by which he is said to have performed such wonders, was nothing more than a typical personification of the brass, assurance, or impudence of the conjuror. The present prima facie economic method is to wear a brazen face with a wooden head. Mettle, it is true, may be necessary, but "cheek" is indispensable.

Modesty is an antiquated virtue, to be repudiated above all others; and humility is only fit for charity-school boys, who learn the "catechiz." But even among these the notion of "humbly, lowly and reverendly," will soon be exploded by the music and dancing system; the new philosophy of the times being, "Jack's as good as his master" and a "tarnation sight better;" every one feels this assurance.

Be assured, gentle readers, there is nothing like brass; it enables a man to put his best leg forward, and a good face upon any thing. Brass is the true philosopher's stone, which turns all it touches into tin. By it the insignificant makes himself important, the empiric becomes a professor, the smatterer a proficient, the mountebank a philosopher, [148] and the quack an oracle; in short, by this rule, "fools rush in where angels fear to tread."

The rule of Assurance is founded upon the fact, that there are no bounds to human credulity; well sustained assumption, with a very small amount of gumption, being alone requisite for miracles in commerce, trade, politics, or religion.

1. Calling on a friend in cold weather, make bold to "roast the boiling piece," by placing your fundamental basis before his parlour fire; lean your back against his "marble," scrape your shoes on his fender, and puff your cigar to the detriment of his elaborate ornaments and gimcracks; as to his wife and children being excluded from the fire, let that be "a part of your religion," fieri facias.

2. Should you be invited to dinner, when you enter the house, walk at once into the dining-room, and make yourself at home by pulling off your boots, calling for a clean pair of shoes, a newspaper, [149] a cigar, and the arm chair; you may nod to the mistress of the house, and say "How do" to the juveniles, if you do not wish to be taken for a brute.

3. Should you call at the house of a friend, during his absence, do not hesitate to mount his best horse, and take a twenty miles' ride for the sake of exercise. When you return, you can "stop dinner" with his wife, and afterwards take her to the Opera.

4. On entering a country church, always patronise the clergyman's or the squire's pew; should any ladies be present, you may take out your eyeglass and quizz them with a vacant stare,—they will probably suppose you to be an unknown friend;—politely hand the fair devotees the prayer and hymn-book; you may also hum the bass in chords to the ladies' treble; when you depart, be sure to make a very low congee, as it will mark you for a gentleman.

5. Should you, by any chance, be introduced to a new acquaintance, you may, at the expiration of a week, jerrymediddle him by the question—"You [150] have not got such a thing as five pounds about you, have you?" A person, who prefers your society to solitude, can have no objection to a loan; you can then make yourself as scarce as asparagus at Christmas.

MUTUAL ASSURANCE.

Assurance is displayed to perfection in modern Assurance Companies; and it only requires assurance to raise a company as baseless as the emasculated minus of No. I., and as fabrickless as a "footless stocking without a leg," which shall be eagerly taken by the public.

The following Prospectus, lately issued by a company in West Middlesex, will afford an example:—

To the Public.—West Middlesex. The Visionary Assurance Company and Utopian Insurance, for the beneficial investment of capital, the insurance of lives, and the manufacture of diamonds out of condensed soap bubbles.

DIRECTORS.

AUDITORS.

SOLICITORS.

SECRETARY.

[153] Royal Flesh and Bones Joint Stock Matrimonial Assurance Company. Patron, Sir Peter Laurie.

The universal Uxorian, Matchmaking and Matchbreaking Company, for the equal and uniform benefit of Maids, Damsels, Wives and Widows.

Schedule A.—

Young Maids with face and fortune, 100; with face without fortune, 900; with fortune without face, 500; with neither face nor fortune, 1,000; damsels ditto, ditto, ditto, ditto, ditto.

Widows with youth and money, 100; with youth and no money, 800; with money and no youth, 600; with neither youth nor money, 1,000.

Old Maids, monied, 100; moneyless, 700; fidgety, with money, 700; fidgety, without money, 1,000.

Young Men with whiskers, mustachoes, money, and connexion, 100; young men with money and connexion, but without whiskers, &c. 800; young men with whiskers, &c., but without money, 1,000; young men without money or whiskers, 600.

Bachelors with rheumatism and money, 500; without rheumatism and with money, 100; without money and with rheumatism, 700; with neither rheumatism nor money, 1,200.

Widowers with families and money, 500; with money and without families, 100; with families and without money, 800; with neither families nor money, 1,100.