(From the Division of Ethnology, Bureau of Science, Manila, P. I.)

Four plates

Beliefs as to the origin of the earth, and of the men, animals, plants, and various topographical features found in it, seem to survive with greater persistence than any other trait of primitive culture. These beliefs lie at the base of nearly all religions, and the myths in which the beliefs are preserved are the foundation of literature. The preservation and study of origin myths is, therefore, of much importance in the reconstruction of the history of mankind which is the chief aim of anthropology.

The peoples of the Philippines have a rich and varied mythology as yet but little explored, but which will one day command much attention. Among the Christianized peoples of the plains the myths are preserved chiefly as folk tales, but in the mountains their recitation and preservation is a real and living part of the daily religious life of the people. Very few of these myths are written; the great majority of them are preserved by oral tradition only.

Until recent years, it has been believed that all ancient records written in the syllabic alphabets which the Filipinos possessed at the time of the Spanish conquest had been lost. It is now known, however, that two of these alphabets are still in use, to a limited extent, by the wild peoples of Palawan and Mindoro; and ancient manuscripts written in the old Bisaya alphabet have been lately discovered in a cave in the Island of Negros. Many of these Negros manuscripts are written myths, and translations of them are shortly to be published. The Bisaya peoples, in general, have preserved their old pagan beliefs to a greater extent than have the other Christian Filipinos, and it is to be [86]hoped that the discovery of these manuscripts will stimulate further investigations.

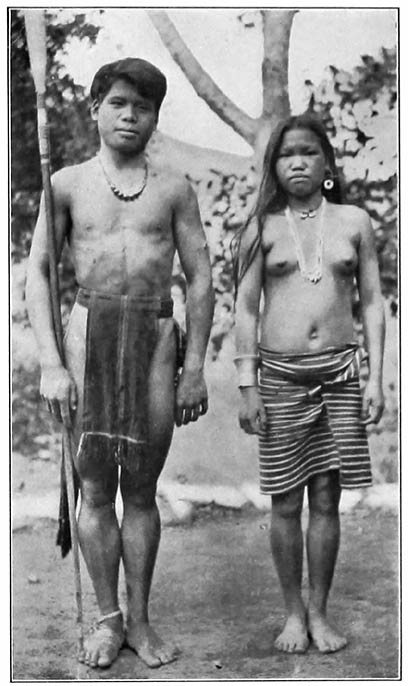

Among the pagan mountain peoples, with which this paper will chiefly deal, there are no written myths except those which have been recorded by Europeans in modern times. Some of the myths are sung or chanted only, while others are repeated in the form of stories. In nearly every case, the repeating of the myths forms an important part of the religious ceremonies of the people. Many different grades of culture are represented among these mountain peoples, and we find a correspondingly unequal development of their mythologies. All classes are represented: primitive, such as the beliefs of the Man͠gyans of Mindoro, the Tagbanwas of Palawan, and the Ilongots of northern Luzon; mediocre, as the beliefs of the pagan tribes of Mindanao; and highly developed, such as the elaborate polytheisms of the Ifugaos, Igorots, Kalingas, and the other peoples of the Mountain Province in Luzon.

Most of the myths and legends recorded here were collected by men well acquainted with the dialect of the people from whom the myth or legend was obtained; they are, therefore, of much greater value than if they had been secured through interpreters.

I shall next discuss a few myths from each of the classes just mentioned.

Our knowledge of the more primitive tribes of the Philippines is very limited and is chiefly confined to the material culture, together with a few of the more obvious social traits. Nothing like a complete study of any one of these tribes has ever been made. Of the Ilongots, most of our knowledge2 is contained in the records of the early Spanish missionaries of the first part of the 18th century, at which time an extensive exploration of the Ilongot country was made.3 There are two modern sources of information: a paper by Worcester,4 which deals chiefly with the material culture, and the notes of Dr. William Jones, who was killed while studying the ethnology of this people. Dr. Jones’ notes are now in the possession of the Field Museum, [87]Chicago, and have not yet been published. Relating to the Man͠gyans, there are three important papers by Worcester,5 Gardner,6 and Miller,7 but these likewise deal chiefly with the material and general social culture, and give only fragmentary notes regarding the religious beliefs. Two papers, one by Worcester8 and one by Venturello,9 relate to the Tagbanwas. The religion of these people is interesting, although primitive. The general character of their beliefs may be seen by the following quotation from Worcester:10

I was especially interested in their views as to a future life. They scouted the idea of a home in the skies, urging that it would be inaccessible. Their notion was that when a Tagbanua died he entered a cave, from which a road led down into the bowels of the earth. After passing along this road for some time, he came suddenly into the presence of one Taliákood, a man of gigantic stature, who tended a fire which burned forever between two tree-trunks without consuming them. Taliákood inquired of the new arrival whether he had led a good or a bad life in the world above. The answer came, not from the individual himself, but from a louse on his body.

I asked what would happen should the man not chance to possess any of these interesting arthropoda, and was informed that such an occurrence was unprecedented! The louse was the witness, and would always be found, even on the body of a little dead child.

According to the answer of this singular arbiter, the fate of the deceased person was decided. If he was adjudged to have been a bad man, Taliákood pitched him into the fire, where he was promptly and completely burned up. If the verdict was in his favour, he was allowed to pass on, and soon found himself in a happy place, where the crops were always abundant and the hunting was good. A house awaited him. If he had died before his wife, he married again, selecting a partner from among the wives who had preceded their husbands; but if husband and wife chanced to die at the same time, they remarried in the world below. Every one was well off in this happy underground abode, but those who had been wealthy on earth were less comfortable than those who had been poor. In the course of time sickness and death again overtook one. In fact, one died seven times in all, going ever deeper into the earth and improving his surroundings with each successive inward migration, without running a second risk of getting into Taliákood’s fire.

I could not persuade the Tagbanuas to advance any theories as to the nature or origin of the sun, moon, and stars. Clouds they called “the breath of the wind.” [88]

They accounted for the tide by saying that in a far-distant sea there lived a gigantic crab: when he went into his hole the water was forced out, and the tide rose; when he came out the water rushed in, and the tide fell. The thing was simplicity itself.

I asked them why the monkey looked so much like a man. They said because he was once a man, who was very lazy when he should have been planting rice. Vexed at his indolence, a companion threw a stick at him which stuck into him; whereupon he assumed his present form, the stick forming his tail.

From the foregoing, it is evident that the Tagbanwa beliefs are not highly developed. However, several items are of interest for comparison with the beliefs of the more cultured tribes to be later described. Of these items, those most to be kept in mind are the idea of a seven-storied underworld, and the name of the chief deity of that underworld, Taliákud. This name comes from the stem tákud, túkud, or tókod, which is common to many Philippine dialects and means “post” or “support.” It is generally applied to the four legs or posts of the common Philippine house. Now, the belief in an Atlas, or god who supports the earth world, is widespread in the Philippines, and the name applied to this god is nearly always derived from this same stem túkud. The Ifugao Atlas is Tinúkud of the underworld, and I suspect that the Tagbanwa Taliákud of the underworld is a deity of the same character.

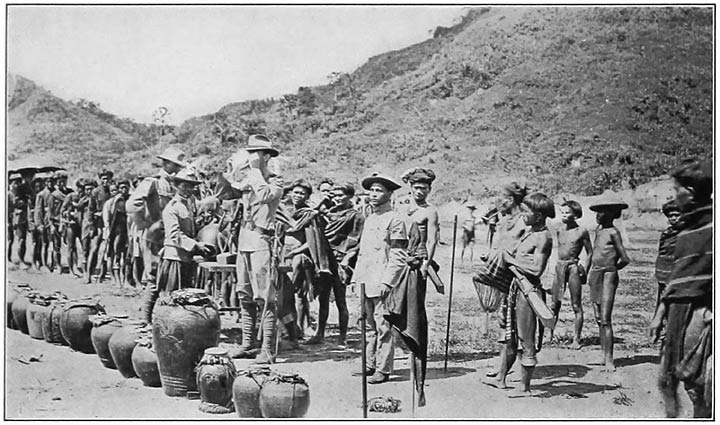

The interior of Mindanao is occupied by some ten pagan tribes, the most important being the Manóbos, Mandayas, Atás, Bagóbos, Biláns, Tirurais, and Subánuns. These tribes are all remarkably alike in culture; much more so, in fact, than any other similar group of peoples in the Philippines; and this culture shows a close resemblance to that of the tribes in the interior of Borneo. In the development of their myths and of their religious beliefs, these peoples occupy a middle position between the more primitive and the highest developed types of the Philippines. John M. Garvan has recently completed a very extensive study of the Manóbo peoples of the Agúsan Valley, in eastern Mindanao, and the following beliefs and myths are quoted from his unpublished notes.

The story of the creation of the world is variable throughout the whole Agúsan Valley. In the district surrounding Talakógon, the creation is attributed to Makalídun͠g, the first great Manóbo. The details of his great work are very meager. He set it up on posts (some say iron posts) with one in the center. At the central post he has his abode, in company with [89]a python, according to the version of some, and whenever he feels displeasure toward men, he shakes the post, thereby producing an earthquake, and at the same time intimating to man his anger. It is believed that, should the trembling continue, the world would be destroyed.

In the same district it is believed that the sky is round and that its extremities are at the limits of the sea. Somewhat near these limits is an enormous hole called the navel of the sea through which the waters descend.

It is said that in the early days of creation the sky was low, but that one day a woman, while pounding rice, hit it with her pestle and it ascended to its present position.

Another version of the creation, prevalent among the Manóbos of the Argauan and Híbun͠g Rivers, gives the control of the world to Dágau, who lives at the four fundamental pillars in the company of a python. Being a woman, Dágau dislikes the sight of human blood, and when it is spilled upon the face of the earth she incites the huge serpent to wreathe itself around the pillars and shake the world to its foundations. Should she become exceedingly angry, she diminishes the supply of rice either by removing it from the granary or by making the soil unproductive.

Another variation of the story to be heard on the Upper Agúsan, Simulau, and Umayan Rivers, has it that the world is like a huge mushroom and that it is supported upon an iron pillar in the center. This pillar is controlled by the higher and more powerful order of diuwáta, who on becoming angered at the actions of men manifest their feelings by shaking the pillar and thereby reminding men of their duties.

Three points in the beliefs just mentioned should be kept in mind. First, the recurrence of the idea that the earth world is supported by a post created by the chief deity and near which he dwells. Second, the belief in the púsod nan͠g dágat, or “navel of the sea,” which is common to all of the pagan tribes of Mindanao and was also known by the ancient Bisáyas, Tagálogs, and other peoples now Christianized. It is extremely probable that this belief originated from some great whirlpool, known to the ancestors of the Philippine peoples or passed by them on their voyages.11 Third, the belief that the sky was once very near the earth, and was raised to its present position by some deity. This belief is also common in northern Luzon.

The idea of the origin of curious-shaped rocks, hills, or mountains by petrifaction of some living animal or plant is common in the Philippines. Garvan gives the two following Manóbo legends of this character:

In the old, old days a boat was passing the rocky promontory of Kágbubátan͠g.12 The occupants espied a monkey and a cat fighting upon the [90]summit of the cliff. The incongruity of the thing suggested itself to them, and they began to give vent to derisive remarks, addressing themselves to the brute combatants, when, lo and behold! they and their craft were turned into rock. To this day the petrified craft and crew may be seen placed upon the promontory, and all who pass must make an offering,13 howsoever small it be, to their vexed souls. To pass the point without making an offering might arouse the anger of its petrified inhabitants, and render the traveler liable to bad weather and rough seas.14

The imitation of frogs is especially forbidden, for it might be followed not merely by thunderbolts but also by petrifaction of the offender, and in proof of this is adduced the legend of An͠gó of Bináoi.15

An͠gó lived many years ago on a lofty peak with his wife and family. One day he hied him to the forest with his dogs in quest of game. Fortune granted him a fine big boar, but he broke his spear in dealing the mortal blow. Upon arriving at a stream, he sat down upon a stone and set himself to straightening out his spear. The croaking of the nearby frogs attracted his attention, and, imitating their shrill gamut, he boldly told them that it would be better to cease their cries and help him mend his spear. He continued his course up the rocky torrent, but noticed that a multitude of little stones began to follow behind in his path. Surprised at such a happening, he hastened his steps. Looking back he saw bigger stones join in the pursuit. He then seized his dog, and in fear began to run, but the stones kept in hot pursuit, bigger and bigger ones joining the party. Upon arriving at his sweet-potato patch, he was exhausted and had to slacken his pace, whereupon the stones overtook him and one became attached to his finger. He could not go on. He called upon his wife. She with the young ones sought the magic lime16 and set it around her husband, but all to no avail for his feet began to turn to stone. His wife and children, too, fell under the wrath of Anítan. The following morning they were stone up to the knees, and during the following three days the petrifying continued from the knees to the hips, then to the breast, and then to the head. Thus it is that to this day there may be seen on Bináoi peak the petrified forms of An͠gó and his family.17

The sun, moon, and stars are great deities, or the dwelling place of such deities, in nearly all Philippine religions. The following Manóbo myth is interesting because of its resemblance to others from northern Luzon. [91]

It is said that in the olden time the Sun and the Moon were married. They led a peaceful, harmonious life. Two children were the issue of their wedlock. One day the Moon had to attend to one of the household duties that fall to the lot of a woman, some say to get water, others say to get the daily supply of food from the fields. Before departing, she crooned the children to sleep and told her husband to watch them but not to approach lest by the heat that radiated from his body he might harm them. She then started upon her errand. The Sun, who never before had been allowed to touch his bairns, arose and approached their sleeping place. He gazed upon them fondly, and, bending down, kissed them, but the intense heat that issued from his countenance melted them like wax. Upon perceiving this he wept and quietly betook himself to the adjoining forest in great fear of his wife.

The Moon returned duly, and after depositing her burden in the house turned to where the children slept but found only their dried, inanimate forms. She broke out into a loud wail, and in the wildness of her grief called upon her husband. But he gave no answer. Finally softened by the loud long plaints, he returned to his house. At the sight of him the wild cries of grief and of despair and of rebuke redoubled themselves until finally the husband, unable to soothe the wife, became angry and called her his chattel. At first she feared his anger and quieted her sobs, but, finally breaking out into one long wail, she seized the burnt forms of her babes, and in the depth of her anguish and her rage threw them to the ground in different directions. Then the husband became angry again, and, seizing some taro leaves that his wife had brought from the fields, cast them in her face and went his way. Upon his return he could not find his wife, and so it is to this day that the Sun follows the Moon in an eternal cycle of night and day. And so it is, too, that stars stand scattered in the sable firmament, for they, too, accompany her in her hasty flight. Ever and anon a shooting star breaks across her path, but that is only a messenger from her husband to call her back. She, however, heeds it not, but speeds on her way in never-ending flight with the marks of the taro leaves18 still upon her face and her starry train accompanying her to the dawn and on to the sunset in one eternal flight.

On myths such as these the religions of the pagan tribes of Mindanao are built up. These religions are by no means primitive, but are accompanied by sacrifices, sometimes human, and the ceremonies are performed by a well-developed priest class.19 [92]

Let us now turn to the highest type of Philippine beliefs:

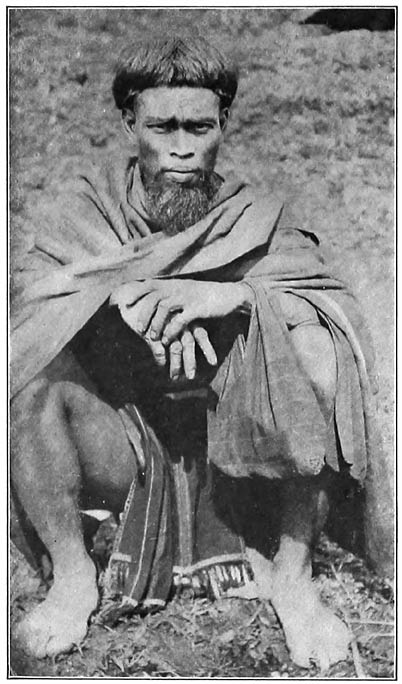

I shall mention chiefly the Igorot, Bontok, and Ifugao peoples, as these three, in addition to holding the highest order of beliefs, are the best developed in general material and social culture of any of the Philippine mountain tribes. The Tin͠ggián, Kalinga, and other tribes in that region also have religions of high type, but our information concerning them is more limited.20

The literature relating to the Igorot-Bontok-Ifugao group is very considerable in extent, and I shall refer only to a few of the more important papers dealing particularly with religion and mythology.

Before taking up the mythology proper, we should have some idea of the religion as a whole. These peoples believe that the regions of the sky world, earth world, and underworld are peopled by an almost incalculable number of deities of varying character and powers. Some of these deities are the great beings who inspire the phenomena of nature, while others are guardian spirits, messenger spirits, or mischievous tricksters. The great nature deities are mostly of malevolent character, and are much feared. Ancestral souls and the souls of sacred animals are looked upon as mediators between gods and men. Pigs and chickens are sacrificed to the deities, and other articles of food and drink are provided for them. Many elaborate religious feasts and ceremonies are held at which priests officiate. The priests form a well-defined class, and in some districts there are also priestesses. A religious ceremony is required for every important act of life, and the priests and priestesses are usually busy people.

It would seem that a religion of this same general type was also common among the lowland peoples of the Philippines before they were Christianized by the Spaniards. Pigafetta, the first European to write of the Philippines, describes a ceremony, which he saw performed in Cebu in the year 1520, as follows:21 [93]

In order that your most illustrious Lordship may know the ceremonies that those people use in consecrating the swine, they first sound those large gongs. Then three large dishes are brought in; two with roses and with cakes of rice and millet, baked and wrapped in leaves, and roast fish; the other with cloth of Cambaia and two standards made of palm-tree cloth. One bit of cloth of Cambaia is spread on the ground. Then two very old women come, each of whom has a bamboo trumpet in her hand. When they have stepped upon the cloth they make obeisance to the sun. Then they wrap the cloths about themselves. One of them puts a kerchief with two horns on her forehead, and takes another kerchief in her hands, and dancing and blowing upon her trumpet, she thereby calls out to the sun. The other takes one of the standards and dances and blows on her trumpet. They dance and call out thus for a little space, saying many things between themselves to the sun. She with the kerchief takes the other standard, and lets the kerchief drop, and both blowing on their trumpets for a long time, dance about the bound hog. She with the horns always speaks covertly to the sun, and the other answers her. A cup of wine is presented to her of the horns, and she dancing and repeating certain words, while the other answers her, and making pretense four or five times of drinking the wine, sprinkles it upon the heart of the hog. Then she immediately begins to dance again. A lance is given to the same woman. She shaking it and repeating certain words, while both of them continue to dance, and making motions four or five times of thrusting the lance through the heart of the hog, with a sudden and quick stroke, thrusts it through from one side to the other. The wound is quickly stopped with grass. The one who has killed the hog, taking in her mouth a lighted torch, which has been lighted throughout that ceremony, extinguishes it. The other one dipping the end of her trumpet in the blood of the hog, goes around marking with blood with her finger first the foreheads of their husbands, and then the others; but they never came to us. Then they divest themselves and go to eat the contents of those dishes, and they invite only women (to eat with them). The hair is removed from the hog by means of fire. Thus no one but old women consecrate the flesh of the hog, and they do not eat it unless it is killed in this way.

This ceremony, almost the same as described by Pigafetta, is in use among the Ifugaos to-day, although it is performed by men instead of by women and differs in a few minor details.

I shall next discuss the religion and mythology of the Igorots, Bontoks, and Ifugaos, treated separately and in more detail.

These people occupy the subprovinces of Benguet, Lepanto, and Amburayan in the Mountain Province. The region of their purest culture is in northern Benguet and eastern Lepanto. Of the religion of this region, we have considerable information from the writings of Fr. Angel Perez, an Augustinian missionary; Sr. Sinforoso Bondad of Cervantes, Lepanto; and a number of personal observations made by myself. [94]

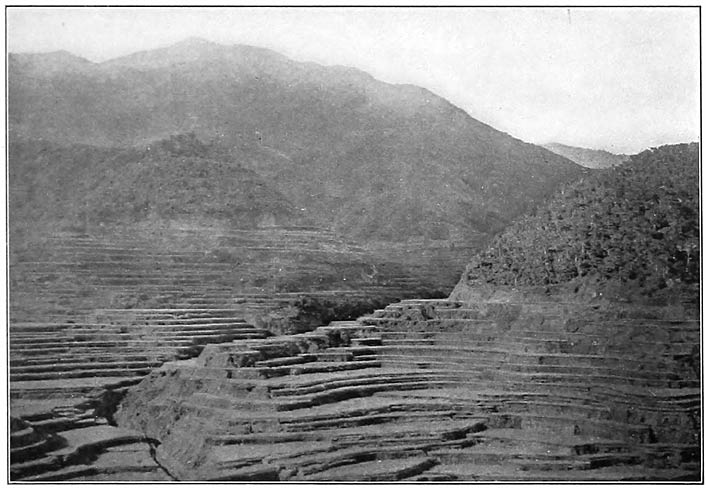

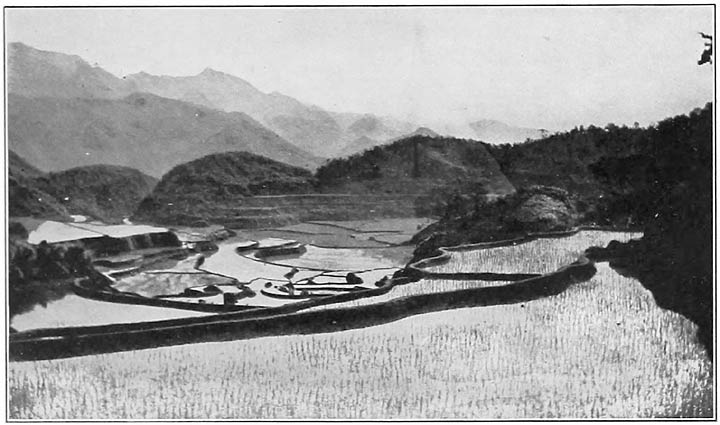

The sun gods, and the deities of the sky world in general, occupy the most important place in the Igorot religion. Place-spirits and animal deities are likewise highly developed. At a place called Kágubátan,22 at the foot of the sacred mountain Múgao in eastern Lepanto, is a small lake full of sacred eels which the people guard with great care. They believe that if these eels were killed the springs would all dry up and they would have no water for their terraced rice fields. The eels are fed every day with rice and sweet potatoes by the children of the village, who, as they approach the lakelet, sing a peculiarly sweet and mournful song, upon hearing which the eels all rise to the surface of the water and approach the shore to receive their food.

The Igorots have both priests and priestesses, and they perform many public and private ceremonies, both for the benefit of the great deities and for the countless minor spirits which inhabit the sacred mountains, cliffs, groves, trees, and bushes that are scattered throughout the Igorot country. Sacrifices of pigs or chickens are made at every ceremony. The ceremonies of the common people are more or less of a private nature, but those of the aristocracy and of wealthy men are nearly always public and general. The greatest ceremonies are those connected with war and marriage and the great public festival which proves a man’s right to the title of nobility.

The Igorots have a high code of morals which is closely associated with their religious belief. They also have a scientific calendar and a considerable knowledge of astronomy which has effected many modifications in their religion. Their mythology is extensive, and they have a rich unwritten literature of epic poems, hero-stories, and historical legends. Most of the myths are too long to be given here, but for purposes of comparison I give the following short one which was collected by the Dominican, Fr. Mariano Rodriguez:

It has been mentioned above that among their tales and stories they preserve a tradition relating to their origin and beginning, after a great and dreadful flood which, a very long time ago, as their old people relate, covered the earth. All the inhabitants except a brother and sister were drowned. The brother and sister, though separated from each other, were saved, the woman on the summit of the highest mountain in the District of Lepanto, called Kalauítan, and the man in a cave of the same mountain. [95]After the water had subsided, the man of the cave came out from his hiding place one clear and calm moonlight night, and as he glanced around that immense solitude, his eyes were struck by the brightness of a big bonfire burning there on the summit of the mountain. Surprised and terrified, he did not venture to go up on the summit where the fire was, but returned to his cave. At the dawn of day he quickly climbed toward the place where he had seen the brightness the preceding night, and there he found huddled up on the highest peak his sister, who received him with open arms. They say that from this brother and sister so providentially saved, all the Igorots that are scattered through the mountains originated. They are absolutely ignorant of the names of those privileged beings, but the memory of them lives freshly among the Igorots, and in their feasts, or whenever they celebrate their marriages, the aged people repeat to the younger ones this wonderful history, so that they can tell it to their sons, and in that way pass from generation to generation the memory of their first progenitors.23

This myth of the great flood, and of the brother and sister who survived it, is common throughout northern Luzon. It is most highly developed by the Ifugaos, as we shall later see.

The Bontoks are sometimes wrongly called Igorots, but have no more right to that name than have the Ifugaos. They are a distinct people, occupying a part of the subprovince of Bontok. They are in some respects unique, and possess certain social institutions and traits which have not been found elsewhere in the Philippines. Most of our information concerning them is contained in the monograph by Jenks;24 in the bulky volume on the language by Seidenadel;25 and in my own observations on the general culture and ethnology of the Bontoks. Jenks’ monograph is excellent as an economic paper, but the few myths given are mostly children’s stories. Seidenadel26 gives several myths in the form of texts, and some of these I have freely translated as follows: [96]

The sons of Lumáwig went hunting. In all the world there were no mountains, for the world was flat, and it was impossible to catch the wild pigs and the deer. Then said the elder brother: “Let us flood the world so that mountains may rise up.” Then they went to inundate at Mabúd-bodóbud. Then the world was flooded. Then said the elder brother: “Let us go and set a trap.” They used as a trap the head-basket at Mabúd-bodóbud. Then they raised the head-basket and there was much booty: wild pigs and deer and people—for all the people had perished. There were alive only a brother and sister on Mt. Pókis. Then Lumáwig looked down on Pókis and saw that it was the only place not reached by the water, and that it was the abode of the solitary brother and sister. Then Lumáwig descended and said: “Oh, you are here!” And the man said: “We are here, and here we freeze!” Then Lumáwig sent his dog and his deer to Kalauwítan to get fire. They swam to Kalauwítan, the dog and the deer, and they got the fire. Lumáwig awaited them. He said: “How long they are coming!” Then he went to Kalauwítan and said to his dog and the deer: “Why do you delay in bringing the fire? Get ready! Take the fire to Pókis; let me watch you!” Then they went into the middle of the flood, and the fire which they had brought from Kalauwítan was put out! Then said Lumáwig: “Why do you delay the taking? Again you must bring fire; let me watch you!” Then they brought fire again, and he observed that that which the deer was carrying was extinguished, and he said: “That which the dog has yonder will surely also be extinguished.” Then Lumáwig swam and arrived and quickly took the fire which his dog had brought. He took it back to Pókis and he built a fire and warmed the brother and sister. Then said Lumáwig: “You must marry, you brother and sister!” Then said the woman: “That is possible; but it is abominable, because we are brother and sister!” Then Lumáwig united them, and the woman became pregnant. They had many children * * * and Lumáwig continued marrying them. Two went to Maligkon͠g and had offspring there; two went to Gináan͠g and had offspring there; and the people kept multiplying, and they are the inhabitants of the earth * * *. Moreover, there are the Mayinit-men, the Baliwan͠g-men, the Tukúkan-men, the Kaniú-men, the Barlig-men, etc. Thus the world is distributed among the people, and the people are very many! * * *

Another story runs as follows:

The brother-in-law of Lumáwig said to him: “Create water, because the sun is very hot, and all the people are thirsty!” Then said Lumáwig: “Why do you ask so much for water? Let us go on,” he continued, “I shall soon create water.” Then they went on, and at last his brother-in-law said again: “Well, why do you not create water? It should be easy, if you are really Lumáwig!” Then said Lumáwig: “Why do you shame me in public?” And then they quarreled, the brothers-in-law. Then they climbed on up the mountain, and at last the brother-in-law said [97]again: “Why do you care nothing because the people are thirsty, and you do not create water?” Then said Lumáwig: “Let us sit down, people, and rest.” Then he struck the rock with his spear, and water sprang out. Then he said to the people: “Come and drink!” And his brother-in-law stepped forth to drink, but Lumáwig restrained him, saying: “Do not drink! Let the people drink first, so that we shall be the last to drink.” And when the people had finished drinking, Lumáwig drank. Then he said to his brother-in-law: “Come and drink.” Then the brother-in-law stooped to drink, and Lumáwig pushed him into the rock. Water gushed out from his body. Then said Lumáwig: “Stay thou here because of thy annoying me!” Then they named that spot ad Isik.27 Then the people went home; and the sister of Lumáwig said to him: “Why did you push your brother-in-law into the rock?” Then said Lumáwig: “Surely, because he angered me!” Then the people prayed and performed sacrifices. * * *

In the above stories we see the recurrence of the flood myth and the origin of fire, or rather the manner in which men received it. The story of bringing water out of a rock is interesting, and occurs again in Ifugao mythology in a slightly different form. It is possible, of course, that this is a biblical story which was brought in by some wandering Christians several generations past; but the flood legend is certainly native, and I see no good reason why the story of the miraculous drawing of water from a rock should not also be a native development in spite of its similarity to the Hebrew myth.

The Bontoks have hundreds of myths and stories about Lumáwig, who corresponds to the Ifugao Líddum, who is the good god who gave men fire, animals, plants, and all the useful and necessary articles of daily life. These myths are of great value, and it is to be hoped that a full collection of them will some day be made.

The Bontok religion is, on the whole, somewhat less developed than that of the Igorots and Ifugaos. The same general beliefs are held, however, and the ceremonial life is similar. Priests are the rule, rather than priestesses; and the same sacred animals are used, as in the other areas. In the social organization, the clan system is in a more perfect state of development than among any other people in the Philippines.

I shall now take up the last religion to be discussed, and the one which is at the same time the most highly developed: [98]

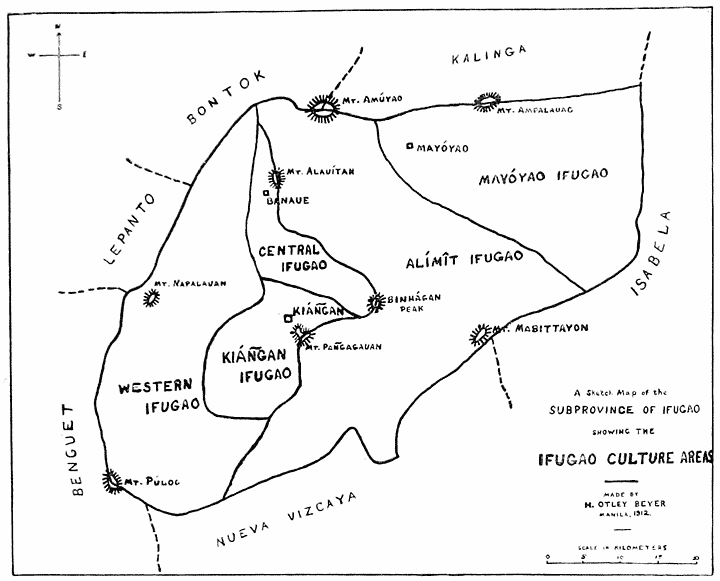

The subject of the Ifugao religion is an extensive one, and I have no intention of discussing it in detail here. I shall merely give a few general facts, and a few of the more interesting myths. In addition to some minor papers by the Dominican fathers Malumbres and Campa, most of our information concerning the Ifugao religion is contained in three extensive manuscript monographs.29 The myths that I shall give here are selected from the first and third of these manuscripts, and the general facts are taken from all three.

The Ifugao conception of the universe differs considerably in the different religious districts.30 The Western Ifugao and Central Ifugao beliefs are closely associated, but stand quite apart from those of Kián͠gan Ifugao. The people of the latter area think of the universe as being composed of a large number of horizontal layers which are very similar one to the other. The upper face of each of these layers is of earth, while the [99]lower face of each of them is of a smooth blue stone called múlin͠g.31 The layer on which we live is called the Earth World (Lúta). The four layers above us constitute the Sky World (Dáya), and are called, in order from the top down, Húdog, Luktág, Hubulán, and Kabúnian. The last is the layer immediately above the Earth World, and it is the blue-stone underfacing of this layer that we call the “sky.” The Under World (Dálom) consists of an unknown number of layers beneath the one on which we live. All of the layers meet in the farthest horizon,32 where lie the mythical regions of the East (Lágud) and other places.

Some of the Kián͠gan priests seem to have developed the further idea that this Dáwi, or farthest horizon, is in the form of a great celestial globe that surrounds the universe, forming its boundary, the inside face of which can be distinguished in the hazy distance where the deep blue of the sky fades into a very light blue or whitish color.33 The Earth World, or layer on which we live, lies approximately at the center of the universe. It is therefore the largest layer, and the layers of the Sky World and Under World grow successively smaller as they approach the zenith and nadir of the celestial globe, the boundary of the universe.34

The inhabitants of the universe consist chiefly of an incalculable number of greater and lesser deities and spirits.35 In addition to these, there are the souls of men, animals, and plants. [100]They have always existed in the various regions of the universe, and were brought to the Earth World by the gods. Men are descended from the gods of the Sky World, as we shall see in the myths.

The mythology of the Kián͠gan Ifugaos is rich and varied. As an introduction to it, I have selected the following:

Origin of the mountains.—The first son of Wígan, called Kabigát, went from the sky region Húdog to the Earth World to hunt with dogs. As the earth was then entirely level, his dogs ran much from one side to another, pursuing the quarry, and this they did without Kabigát hearing their barking. In consequence of which, it is reported that Kabigát said: “I see that the earth is completely flat, because there does not resound the echo of the barking of the dogs.37” After becoming pensive for a little while, he decided to return to the heights of the Sky World. Later on he came down again with a very large cloth, and went to close the exit to the sea of the waters of the rivers, and so it remained closed. He returned again to Húdog, and went to make known to Bon͠gábon͠g that he had closed the outlet of the waters. Bon͠gábon͠g answered him: “Go thou to the house of the Cloud, and of the Fog, and bring them to me.” For this purpose he had given permission beforehand to Cloud and Fog, intimating to them that they should go to the house of Baiyuhíbi,38 and so they did. Baiyuhíbi brought together his sons Tumiok, Dumalálu, Lum-údul, Mumbatánol, and Inaplíhan, and he bade them to rain without ceasing for three days. Then Bon͠gábon͠g called to X ... and to Man͠giuálat, and so they ceased. Wígan said, moreover, to his son Kabigát: “Go thou and remove the stopper that thou hast placed on the waters,” and so he did. And in this manner, when the waters that had covered the earth began to recede, there rose up mountains and valleys, formed by the rushing of the waters.39 Then Bon͠gábon͠g called Mumbá’an that he might dry the earth, and so he did.

The first inhabitants of the Earth World.—Such being the state of affairs, Kabigát went to hunt once again; and, while following the dogs, that were chasing a quarry, he made a thrust with his spear into a [101]spring (or fountain) at the foot of a large tree. Immediately Kabigát returned to Húdog, bringing with him the captured quarry. When he had dressed and eaten the savory game, Kabigát said to his father Wígan that he had seen on the Earth World a spring and very good and beautiful trees for timber with which to make houses, and that accordingly he was desirous of going down to live at such a delightful place. His father answered him that if he so desired he might do so.

Some time after Kabigát had departed, and after he had cut excellent timber wherewith to build a house, Wígan said to his daughter Búgan: “Look, daughter! Thy brother Kabigát is down in Kai-án͠g building a house. I think that it would behoove thee to look after his meals.” Búgan volunteered to descend with such a design. This intention having been carried out, she lodged herself in the upper part of the house, and her brother dwelt in the lower part.

In the meantime, Kabigát, reflecting on his solitude and want of company, and, seeing that the domestic chickens, even though related among themselves, produced other roosters and hens, resolved to know carnally his sister Búgan, during her sleep. Some time having expired, the sister noted that she had fruit in her womb. * * * Such was the sadness and melancholy that came upon her, that she did nothing else but to weep and bewail herself, and to seek by some means alleviation for her sorrow through a violent death. She pretended to her brother that she was going to look for ísda,40 but what she did was to follow the course of the river until she arrived at its mouth in Lágud (the Eastern World). Upon arriving at the shore of the sea, she remained there weeping and waiting for someone to take away her life in a violent way. Soon her brother Kabigát (who had followed her) appeared there, and Búgan, upon discerning him, cast herself into the depths; but, instead of going to the bottom, she stopped at the rice granary of N͠gílîn Man͠gón͠gol. The brother, who witnessed the tragedy, did not stop at trifles but at once cast himself after her into the depths of the ocean, stopping, by a strange coincidence, at the very same rice granary as his fugitive sister and spouse. She continued there, bemoaning her misfortune, when, behold! N͠gílîn, hearing her plaint, approached and inquired the cause of her affliction. She related to him her trouble, how she had conceived by her carnal brother when she was asleep. N͠gílîn soothed her as follows: “Do not be afflicted, daughter, by that. Are not the fowls of Kai-án͠g related among themselves, and yet they beget just like those that are not so?” The maiden became somewhat calm, but still, out of shame for what had happened, she refused to eat what N͠gílîn offered her. Then he said to her: “In order that thou mayst further assure thyself of what I tell thee, and in order that thou mayst quiet thyself, let us go and consult my elder brother Ambúmabbákal.” And so they did. Ambúmabbákal, having been informed of the circumstances, burst out laughing and said to them: “Peradventure have ye not done well and righteously, there not being in existence any others but yourselves to procreate? However, for greater assurance, let us all go together to [102]set forth the case before Muntálog my father.” Muntálog, having heard their story, applauded the conduct of the solitary brother and sister. He told them, accordingly, to calm themselves and to rest there for a few days,—and so they did.

The bringing of fire to the Earth World.—On the third day, Kabigát requested leave to return, but Muntálog answered: “Wait one day more, until I in my turn go to my father Mumbónan͠g.” Muntálog found his father and mother seated facing each other; and, upon his arrival, his mother, Mumboniag, came forward and asked him: “What news do you bring from those lower regions, and why do you come?” The father also became aware of the presence of his son, through the questioning of the mother, and inquired likewise as to the reason of his coming. Muntálog answered: “I have come, father, to ask thee for fire for some Ifugaos who remain in the house of Ambúmabbákal.” “My son,” the father replied, “those Ifugaos of yours could not arrive at (or, come to) Mumbónan͠g without danger of being burned to cinders.” Then he continued: “It is well! Approach me!”41 Muntálog accordingly approached Mumbónan͠g, who said to him: “Seize hold of one of those bristles that stand out from my hair,” and so Muntálog did, noticing that the said point faced the north, and he placed it in his hand. Then Mumbónan͠g said to him again: “Come nigh! Take this white part, or extremity, of the eye that looks toward the northeast, toward the place called Gonhádan.” And he took it and placed it in his hand. And Mumbónan͠g said to him once more: “Come near again, and take the part black as coal, the dirt of my ear which is as the foulness of my ear.” And so he did. Then Mumbónan͠g said to Muntálog: “Take these things and bring them to thy son Ambúmabbákal and to N͠gílîn, in order that the latter may give them to the Ifugaos.” And he said again to Muntálog: “Take this white of my eye (flint), this wax from my ear (tinder), and this bristle or point like steel for striking fire, in order that thou mayst have the wherewith to attain what thou seekest (that is, fire), and to give gradually from hand to hand to the Ifugao; and tell him not to return to live in Kai-án͠g, but to live in Otbóbon, and cut down the trees and make a clearing there, and then to get together dry grass; and that they make use of the steel for striking fire, holding it together in this manner, and burying it in the grass. And on making the clearing if they see that snakes, owls, or other things of evil omen approach, it is a sign that they are going to die or to have misfortunes. But if they do not approach them, it is a sign that it will go well with them in that place; that the soil will be productive, and that they will be happy.”

The journey to Ifugao land from the East.—Upon the return of Muntálog, at the termination of the fourth day, he said to Búgan and Kabigát: “Now ye can go but let N͠gílîn and Ambúmabbákal accompany [103]you as far as the house of Lin͠gan,42 in order that there they may make the cloth or clothes necessary for wrapping the child according to the usage of the Earth World.”

Lin͠gan actually furnished to them the cloth and the seamstress to make the swaddling clothes for the child—and then they continued their journey unto the house of Ambúmabbákal. The latter said to them: “Take this cloth and this pair of fowls, male and female, and do not return to live at Kai-áhan͠g but go to Otbóbon.” And Ambúmabbákal accompanied them to the house of N͠gílîn á Man͠gón͠gan43 and said to the latter: “It will be well if we beseech the búni44 to take pity on these poor people, considering the great distance that still remains to them unto Otbóbon, and keeping in mind also the great heat that prevails.” So they did, saying: “Ye búni, take pity upon these unhappy ones and shorten for them the distance.” The prayer was heard, and after two or three days they found themselves at the end of their journey.

The peopling of Ifugao land.—Having arrived at Otbóbon, they built a temporary hut on fertile land. Later they constructed a good house, and it was just after it was finished that Búgan gave birth to a healthy boy; and the fowls also procreated.

The child grew a little, but there came to him an unlooked-for sickness. Then Kabigát remembered that Ambúmabbákal had advised them to offer fowls to their ancestors in case any sickness should come upon them. So they killed a rooster and a hen, and offered them to Ampúal, Wigan, and their other ancestors. The child recovered and began to grow very robust and plump. They named him Balitúk. Búgan conceived again, and she gave birth to a strong girl, to whom she gave the name of Lin͠gan. These children grew up, and, having attained a marriageable age, were married like their parents, and gave origin to the Silipanes.45

Their parents, Kabigát and Búgan, had a second son, on whom they placed the name Tad-óna, and then another daughter, whom they called Inúke. She and Tad-óna did what their parents and brother and sister had done, and gave birth to Kabigát, the second, and Búgan, the second. These latter two, imitating the preceding ones, were united in wedlock and begot sons and daughters who peopled the remainder of the Ifugao region.46

Establishment of religious ceremonies.—Upon their marriage Tad-óna and Inúke did not offer pigs or fowls to the búni as was customary. This being observed by Líddum from Kabúnian, he descended and asked them: “Why have ye not offered sacrifices?” They answered him that they were ignorant of such a custom or ceremony. Then Líddum returned to Kabúnian [104]and brought them the yeast with which to make búbûd, or wine from fermented rice; and he taught Tad-óna the method of making it, saying: “Place it in jars on the third day,” and he returned to the Sky World. On the fifth day he came down again to teach them the manner of making the mum-búni.47

Some version of the above myth is known to the people of every Ifugao clan, although the details of the story vary considerably in the different culture areas. The myth is also known to the Igorots and Bontoks, as we have already seen. I have in my possession some twenty different versions that have been collected from various clans of Central, Western, and Kián͠gan Ifugao. These may all be classified into two general types, one of which is represented above.48 An example of the other type, entitled The Ifugao Flood-Myth, is given later in this paper under the heading Central Ifugao Beliefs.

The god Wígan is one of the greatest and best known figures in Ifugao mythology. He has three sons, Kabigát, Balitúk, and Ihîk, and one daughter, Búgan. The following story about Ihîk is especially interesting because of its resemblance to one of the Bontok myths previously given.

Ihîk nak Wígan, in company with his brothers Kabigát and Balitúk, went to catch fish in the canal called Amkídul at the base of Mt. Inúde. After catching a supply of fish, they strove to ascend to the summit of the mountain; but, ever as they went up, Ihîk kept asking his brothers for water to satiate his devouring thirst. They answered him: “How can we find water at such an elevation? Water is found at the base of the mountains but not at their summits!” But Ihîk kept on importuning them. At last, when they were in the middle of their ascent, they came to an enormous rock. Balitúk struck the rock with his spear, and instantly there burst forth a large jet of water.

Ihîk desired to drink first but they deterred him, saying: “It is not just that thou shouldst drink first, being the last born of us brothers!” Then Kabigát drank, and afterwards Balitúk. Just as Ihîk was about to do so, Balitúk seized him and shoved the whole of his head under the rock, adding: “Drink! Satiate thyself once for all, and serve henceforth as a tube for others to drink from!” And so it came to pass that Ihîk on receiving the water through his mouth sent it forth at the base of his trunk. He said to his brothers: “You are bent on making me take the part of a water-spout! I shall do so, but bear in mind that I shall [105]also take just vengeance on your descendants for this injury.” In view of this threat, Kabigát and Balitúk did not dare to make use of the improvised fountain, and so they returned home.

This myth, which is very long, then relates how certain of the great deities befriended Ihîk by setting him free and assisting him in obtaining vengeance on his brothers and their descendants.

Another myth, showing an interesting resemblance to a Manóbo myth already given, tells how the sky region of Manaháut,50 which was once very near the Earth World, was raised to its present position. The cannibalistic and voracious appetite of Manaháut was causing the slow extermination of the human race,51 and the aid of the gods was invoked. The Ifugaos have a number of powerful deities who always remain in a sitting posture. One of these suddenly rose up, and, with his head and shoulders, thrust the sky region of Manaháut to a vast height above the earth, thereby preventing the extermination of the people.52

As a final example of Kián͠gan Ifugao mythology, I give the following story which is one of the best specimens of Ifugao literature.

The wife of the god Hinumbían is Dakáue. She has no children except a daughter called Búgan. This Búgan was with her parents in Luktág. Let it be noted that these divinities of the highest region of the Sky World do not see directly that which takes place in the lower spheres, but the first calls the second, and the second the third, etc. [106]According to this order, the first or principal god, known as Bun͠gón͠gol, charges or gives orders to his son Ampúal, who in turn orders his son Balittíon, and the latter orders and charges Líddum of the lowest sky region, or Kabúnian. This Líddum is the one that communicates directly with the Ifugaos. The said Búgan, daughter of Hinumbían, was at that time a maiden, while in Luktág, and her uncle Baiyuhíbi54 told her to go down and amuse herself in the third sky region, Hubulán. So, according to the wishes of her relatives, she went down to Hubulán where Dologdógan, the brother of Balittíon, was. The said Dologdógan had gone to Hubulán to marry another Búgan. The first Búgan, daughter of Hinumbían, had been advised to marry in Luktág, but she did not wish to do so, and so they told her to go off and divert herself in Hubulán. Having settled down in this sky region, her uncles advised her to get married there, but neither did she wish this. In view of her attitude on this question, Dologdógan exhorted her to descend to Kabúnian, and go to take her abode in the house of Líddum her relative and the son of Amgalín͠gan. The said Líddum wished her to marry in Kabúnian, but she also refused to do this. Near the house, or town, of Líddum (whose wife is called Lin͠gan) there was a village called Habiátan, and the lord of the village also bore this name. Such being the case, the said Habiátan went to the house of Líddum, and, upon seeing the young Búgan in the condition of maidenhood, he asked Líddum: “Why does this maid not marry?” The former answered him: “We have counseled her to it, but she does not wish to do so. I, upon seeing that she did not wish to get married, nor to follow my advice, said to her: ‘Why dost thou not get married?’ She began to laugh. I replied: ‘Then, if thou dost not wish to get married in Kabúnian, it were better for thee to return to thy people and thy family of Luktág,’ but she answered: ‘That is not necessary, and I should like to stay with thee in thy house—and I shall take care to get married at my pleasure, when I see or meet someone of my liking, and then I shall tell thee.’” Habiátan, after hearing this story of Líddum, said to him: “According to this, I shall take the young Búgan to my rancheria and house in Habiátan to see if she wishes to marry my son Bagílat.”55 To which Líddum rejoined: “If Búgan so desire, it goes without saying that she can accompany thee at once.” The maiden having been consulted, assented, and went off with Habiátan to his house and village. Having arrived at the said place, and after Búgan had observed somewhat the young Bagílat, as if Habiátan had asked her whether she desired to marry him, she answered: “How am I to wish to marry him (Bagílat), grim and fierce as he is, and making use of such an extraordinary spear! Moreover, he never stops—but is always running around in all parts of the Sky World, through the north and the south, through the east and the west;” and she told Habiátan that she did not wish to marry his son Bagílat, the Lightning, because that through his effects he harmed plants, fruits, and possibly might injure even herself. Then said Habiátan: “Thou art somewhat fastidious, and I see that thou couldst with great difficulty get married in these regions; it would be better that thou return once more to thy land.” She answered that she did not desire to return any more to her people, and that accordingly she would betake [107]herself to some other point more to her liking. This dialogue being completed, she went down from the house of Habiátan, and, casting a glance at the four cardinal points, she saw that the weather was clear and calm, and descried on the Earth a place called Pan͠gagáuan, over (or on) Umbuk, where there was an Ifugao called Kin͠ggáuan—a young man, unmarried, naked, and without a clout (which he had thrown away because of its age), because he was engaged in making pits, or wells, for catching deer with a trap (according to the custom)—and there he had a hut. Upon seeing him Búgan exclaimed: “Oh! the poor man! and how unfortunate!” And, hiding the occurrence from Habiátan, she determined to return to her sky region of Luktág in order to manifest to her father, Hinumbían, that it was her desire to descend to the Earth World in order to get married with that poor Ifugao.

The paternal permission having been obtained, she made ready the necessary provisions—consisting of a vessel of cooked rice and a clout (or bahág). In this fashion she proceeded to Kin͠ggáuan’s hut and entered it, saying: “Who is the owner of this hut?” “I,” answered Kin͠ggáuan, “but I am ashamed to approach thee, because thou art a woman and I am naked.” To which she replied: “Never mind! because here I have a clout for thee.” But he did not approach for shame; and so she threw him the clout from afar, in order that he might cover himself. The surprised man expressed to her his astonishment, saying: “Why dost thou approach here, knowing that the appearance of a woman, when men are engaged in such an occupation, is of evil omen for the hunt?”56 And she replied to him: “By no means shall it come to pass as thou thinkest, but, on the contrary, thou shalt be extremely lucky in it. For the present let us eat together, and let us sleep this night in thy hut. To-morrow thou shalt see how lucky we are in the hunt.” The following day, upon going to visit the pits, they actually found them full. Kin͠ggáuan killed the quarry and spent the rest of the day in carrying the carcasses to his hut. He kept alive only two little pigs, a male and a female, which he delivered to Búgan that she might tie them in the dwelling-place while he was bringing in the rest of the dead game. On the second day Búgan asked the solitary one: “Why dost thou dwell in such evil places?” Kin͠ggáuan answered her: “Because my parents are so parsimonious in giving me what I need.” Then said Búgan to him: “Let us go to Kián͠gan,” and he consented. Leaving, then, the dead game in the hut, they carried with them only the two live “piglets.” Kin͠ggáuan carried the male one, and Búgan the female one—arriving at the above-mentioned place on the nightfall of the second day.

Having arrived at Kián͠gan, they took up their lodging in the house of Kin͠ggáuan’s mother—the man entering first and then Búgan. The mother of the former was surprised, and asked him: “Who is this woman?” The son answered: “I was at the hunting place and she presented herself to me there and I do not know whence she comes.” The aged mother after having looked at them a little while—when seated—addressed herself to Búgan and asked: “Who art thou? How dost thou call thyself? From [108]whence dost thou come?” The maiden replied that her name was Búgan, that she was the daughter of Hinumbían and Dakáue, and that she belonged to the sky region of Luktág. But the reason of her descent to that terraqueous region, and of accompanying her son, was her having seen him so poor and deserted * * * “for which reason I took pity on him and came down to visit him and to furnish him with an abundance of game” * * * and she added that on the following day the mother should send many people to collect the dead game which they had left in the lonely hut of her son. By a coincidence, the mother of the young man was also called Búgan, with the addition of na kantaláo.

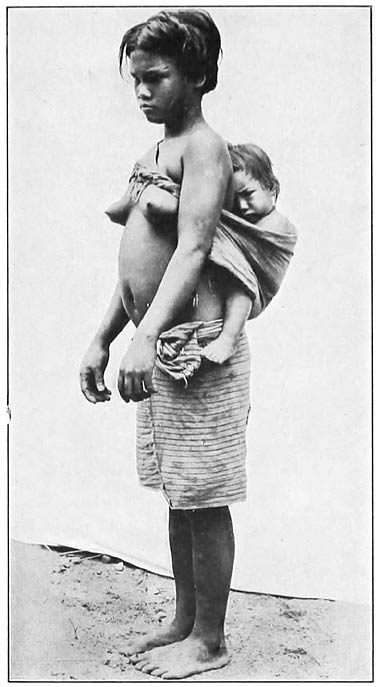

During all this, the young couple had already been united in the bond of matrimony—without any of the prescribed formalities—at the place called Pan͠gagáuan, and Búgan gave birth to a vigorous son to whom she gave the name Balitúk. The little pigs, also, which they had brought, gave forth their fruit. The child grew a little, but he did not yet know how to walk. His mother, Búgan, as a being from the Sky World, did not eat like the rest of the people of Kián͠gan, but desired only boiled rice, birds, and meat of game. Those of that region bore her much envy because of her being a stranger; and, because they knew she did not like certain vegetables of theirs, they strove to make her depart from their town and to betake herself to her birthplace of Luktág in the sky. Their envy toward her increased upon their seeing the abundance of her fowls and pigs. With the object, then, of disgusting her, and of driving her away, they attempted to surround her house with certain garden stuffs, greens, and fish. With these they succeeded effectively in making Búgan fall sick with an intense itch and fever; for which reason she abandoned that house and went to another place, while her husband moved to a rice granary. But they persecuted her again in her new place of lodging, surrounding it with the vegetables and other things spoken of above, and causing her nausea in a stomach accustomed to other food. In view of such wearisome tricks, Búgan proposed to Kin͠ggáuan her desire to return to her land with the new blossom of spring, their child. Her husband answered her: “I should well like to accompany thee, but I am afraid of ascending to so high a place.” “There is no reason to be afraid,” replied Búgan, “I myself shall take thee up in the áyud (a kind of hammock).” She accordingly strove to persuade him, but Kin͠ggáuan did not lay aside his fear; then she attempted to take him up bound to a rope, but neither did she effect this. During these labors, she soared aloft with the child to the heights of Luktág, but upon perceiving that her husband had not followed her she went down again, with her son in the band which the Ifugaos use for that purpose. (Plate III, fig. 2.) After conferring with Kin͠ggáuan, she said to him: “Thou seest the situation. I cannot continue among thy countrymen, because they hate me unto death. Neither dost thou dare to ascend unto Luktág. What we can do is to divide our son,” * * * and, seizing a knife, Búgan divided her son Balitúk in the middle, or just above the waist, and made the following division: The head and the rest of the upper trunk she left to Kin͠ggáuan—that it might be easier for him to give a new living being to those upper parts—and she retained for herself the lower part of the trunk unto the feet; and as for the entrails, intestines, heart, liver, and even the very excrement, she divided [109]them—leaving the half for her husband. The partition having been completed, Búgan mounted to her heavenly mansion, taking with her the part of her son which fell to her lot, and, giving it a breath of life, she converted it into a new celestial being retaining the very name of Balitúk. On the other hand, the part which she had left to her husband, on the earth, began to be corrupted and decayed, because he, Kin͠ggáuan, had not been able, or did not know how, to reanimate it. The foul odor of the putrified flesh reached unto the dwelling place of Búgan in Luktág, and, having been perceived by her, she descended to Kabúnian in order to better acquaint herself with the happening. From Kabúnian she saw that the evil odor issued from the decomposition of the part of the entrails which she had left on the earth in charge of her husband, and which he had not reanimated. Then she broke forth in cries of grief, pity, and compassion—and, descending to Kián͠gan, she severely accused Kin͠ggáuan, saying unto him: “Why hast thou allowed our son to rot? And why hast thou not quickened him to life?” Upon which he answered that he did not understand the art of reanimation.

Búgan endeavored to remove the greatest possible portion of the corrupted part of her son. Consequently, she changed the head of Balitúk into an owl57—a nocturnal bird called akúp by the Ifugaos—whence the origin of the Kián͠gan custom of auguring evil from this bird, and the offering of sacrifices of fowls to Búgan, in order that no harm should come to them, and that the said owl should not return to them.

The ears she threw into the forest, and for that reason there come forth on the trees certain growths, like chalk, half spherical (certain species of fungi). The nose she threw away and changed it also into a certain species of shell which attaches itself to trees. Of the half of the excrement she made the bill of a small bird called ido, from which the Ifugaos augur well or ill, according to certain variations of its song.58

From the putrified tongue she produced a malady, or swelling, of the tongue in men, which is cured with a hot egg, or with a chicken, which they offer to their mother, Búgan.

From the bones of the breast she created a venomous serpent. From the heart she made the rainbow. From the fingers she made certain very long shells, after the form of fingers. From the hair, thrown into the water, she created certain little worms or maggots. From the skin she drew forth a bird of red color, called kúkuk. From the half of the blood she created the small bats (litálît). From the liver she drew [110]forth a certain disease of the breast. From the intestines she formed a class of somewhat large animals, resembling rabbits or rats (amúnîn?). From the bones of the arms she made pieces of dry or rotted wood that fall from trees upon passers-by who approach them.

The Balitúk that Búgan reanimated is in the sky region of Luktág.59

The myth just given is an example of one of the most interesting processes in the early development of literature. It is probable that originally it was only a simple origin myth, but it has been elaborated and developed until now it is worthy of its little niche in the world’s literature. [111]

The exact difference between the Central Ifugao and the Kián͠gan beliefs is not an easy matter to determine. There has been much mixture between the two peoples accompanied by a corresponding exchange of ideas. The effect of this exchange in some cases has been to produce a deceptive similarity in beliefs and myths that originally were fundamentally different; while in other cases myths that were originally the same have been so greatly differentiated in the two areas that their unity can scarcely be recognized.

However, it would seem that some basic differences really exist, and the probability is that they are survivals from the ancient cultures of the peoples who went to make up the present distinctly composite Ifugao group. But the evidence at hand is not sufficient to warrant a full discussion of this question here, and I shall merely cite one example. Kián͠gan myths are nearly always told from the standpoint of the gods, and have to do with the dealings of the gods with one another and with men. On the other hand, Central Ifugao myths are told from the standpoint of men in their relations and dealings with the gods. This will be made plain by a comparison of the following Central Ifugao myth with the Origin of the Ifugaos previously given.

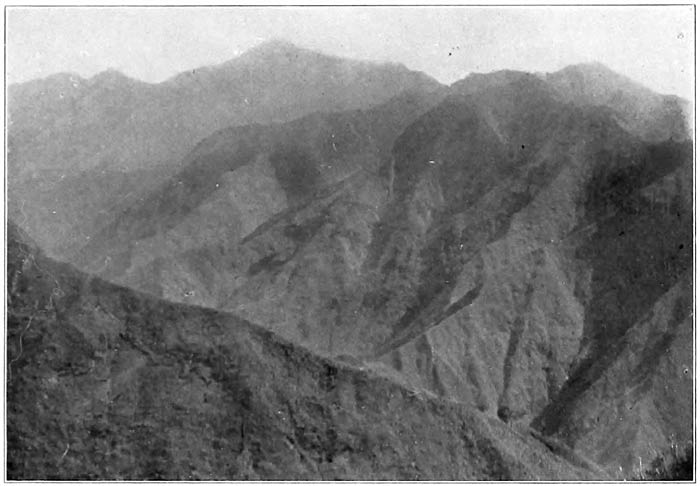

The Golden Age.—Ifugao knowledge of the prediluvian period is very vague. It is known, however, that the Earth World was entirely flat except for two great mountains, one in the east called Amúyao and one in the west called Kalauítan.61 This level country was heavily forested, and all of the people lived along a large river that ran through the central plain between the two great mountains.

The period was something like a Golden Age, when things were much better than they are now. The people were demigods whose life was a happy one and their country a sort of Garden of Eden. To obtain rice, all that they needed to do was to cut down a stalk of bamboo, which was plentiful, and split open the joints which were filled with hulled rice ready to cook. Stalks of sugar-cane were filled with baiyax,62 and needed only to be tapped to furnish a most refreshing drink. The river was full of fish, and the forests were filled with deer and wild hogs [112]which were much easier to catch than those of the present day. The rice grains of that time were larger and more satisfying, and a handful of them was sufficient to feed a large family.

But this Golden Age, like others, was not destined to last.

The flood, and the origin of the mountains.—One year when the rainy season should have come it did not. Month after month passed by and no rain fell. The river grew smaller and smaller day by day until at last it disappeared entirely. The people began to die, and at last the old men said: “If we do not soon get water, we shall all die. Let us dig down into the grave of the river, for the river is dead and has sunk into his grave, and perhaps we may find the soul of the river and it will save us from dying.” So they began to dig, and they dug for three days. On the third day the hole was very large, and suddenly they struck a great spring and the water gushed forth. It came so fast that some of them were drowned before they could get out of the pit.

Then the people were happy, for there was plenty of water; and they brought much food and made a great feast. But while they were feasting it grew dark and began to rain. The river also kept rising until at last it overflowed its bank. Then the people became frightened and they tried to stop up the spring in the river, but they could not do so. Then the old men said: “We must flee to the mountains, for the river gods are angry and we shall all be drowned.” So the people fled toward the mountains and all but two of them were overtaken by the water and drowned. The two who escaped were a brother and sister named Wígan and Búgan—Wígan on Mt. Amúyao and Búgan on Kalauítan. And the water continued to rise until all the Earth World was covered excepting only the peaks of these two mountains.

The water remained on the earth for a whole season or from rice planting to rice harvest.63 During that time Wígan and Búgan lived on fruits and nuts from the forests that covered the tops of the two mountains. Búgan had fire which at night lit up the peak of Kalauítan, and Wígan knew that there was someone else alive besides himself. He had no fire, and suffered much from the cold.

At last the waters receded from the earth and left it covered with the rugged mountains and deep valleys that exist to-day; and the solitary brother and sister, looking down from their respective peaks, were filled with wonder at the sight.

The repopulation of the Earth World.—As soon as the earth was dry, Wígan journeyed to Kalauítan where he found his sister Búgan, and their reunion was most joyous. They descended the mountain and wandered about until they came to the beautiful valley that is to-day the dwelling place of the Banáuol clan—and here Wígan built a house. When the house was finished, Búgan dwelt in the upper part and Wígan slept beneath.

Having provided for the comfort of his sister, Wígan started out to find if there were not other people left alive in the Earth World. He [113]traveled about all the day and returned to the house at night to sleep. He did this for three days, and then as he was coming back on the third evening he said to himself that there were no other people in the world but themselves, and if the world was to be repopulated it must be through them. * * * At last Búgan realized that she was pregnant. She burst into violent weeping, and, heaping reproaches on his head, ran blindly away toward the East, following the course of the river. After traveling a long way, and being overcome with grief and fatigue, Búgan sank down upon the bank of the river and lay there trembling and sobbing.64 After having quieted herself somewhat, she arose and looked around her, and what was her surprise to see sitting on a rock near her an old man with a long white beard! He approached her and said: “Do not be afraid, daughter! I am Maknón͠gan, and I am aware of your trouble, and I have come to tell you that it is all right!” While he was speaking, Wígan, who had followed his sister, appeared on the scene. Then Maknón͠gan placed the sanction and blessing of the gods upon their marriage, assuring them that they had done right, and that through them the world must be repeopled. He told them to return to their house, and whenever they were in trouble to offer sacrifices to the gods. After Búgan had become convinced in this manner, they left Maknón͠gan and returned home.

In the course of time nine children were born to Wígan and Búgan, five sons and four daughters. The four oldest sons married the four daughters, and from them are descended all of the people of the Earth World. The youngest son, who was named Igon, had no wife.65

The sacrifice of Igon.—One year the crops failed, there was much sickness, and everything went wrong. Then Wígan remembered the advice of Maknón͠gan, and he told his sons to procure an animal for the sacrifice. They caught a rat and sacrificed it, but the evil conditions were not remedied. Then they went out into the forest and captured a large snake and sacrificed it to the gods, but the disease and crop failure still continued. Then Wígan said: “The sacrifice is not great enough, for the gods do not hear! Take your brother Igon, who has no wife, and sacrifice him!” So they bound Igon, and sacrificed him, and called upon the gods. And Maknón͠gan came, and all the other great gods, to the feast. And they took away the sickness, and filled the granaries with rice, and increased the chickens, the pigs, and the children. Then Maknón͠gan said to the people: “It is well, but you have committed an evil in spilling human blood and have thereby brought war and fighting into the world. Now you must separate to the north, south, east, and west, and not live together any more. And when ye have need to sacrifice to the gods, do not offer rats, snakes, or your children, but take pigs and chickens only.”

And one of the sons of Wígan went to the north, and one to the south, and one to the east, and one to the west; and from them are descended the peoples of the Earth World, who fight and kill one another to this day because of the sacrifice of Igon.

[114]

Many other illustrations might be given of the differences between the Central and Kián͠gan Ifugao religious conceptions, but the above will suffice for the purposes of the present paper.66

One more type of Ifugao origin myth merits our attention before we come to the conclusion. This type consists of the myths invented to explain the origin of the ancient Chinese jars, bronze gongs, amber-agate beads, and other rare articles of foreign manufacture on which the Ifugaos place a high value, and the origin of which they do not know. Many of these objects have been in the possession of the people for at least several hundred years. They were probably brought into the Islands by Chinese traders centuries before the coming of the Spaniards, and gradually found their way to the Ifugaos through the medium of their cursory commerce with the surrounding peoples.67

One of these myths, explaining the origin of three well-known jars, runs as follows.

A long time ago, before the coming of the Spaniards, there lived at Hinagán͠gan a man called Ban͠ggílît. He was a wealthy man, possessing four rice granaries and a very large house; but he was not a priest. His constant desire was to hunt in the forest.

One day Ban͠ggílît went hunting in the forest and was overtaken by night. He called his dogs but they did not come. He made fire, cooked, and ate. Then one dog came to him, and he took it in lead and departed. Near by he found a path. The dog with him barked and the second dog answered, and they went on. And the dog with Ban͠ggílît began to [115]whimper and whine, and to pull on the leash; and Ban͠ggílît ran, and they went on. Suddenly it became light all around them, and they came out of the forest into a large group of people. And the people said among themselves: “Surely Ban͠ggílît is dead,” and they examined his body and asked: “Where were you speared?” And Ban͠ggílît spoke and said: “I have not been speared! I went hunting and was overtaken by night, and my dog here ran ahead on our path. I followed, and came here, and lo! it is light here!”

And they took Ban͠ggílît and went to their town—for there are many large towns there in the dwelling-place of souls. They wished to give him food, but he said: “Wait until my own food is exhausted, and then I will eat of your rice here.” And they asked him: “How many days will you remain with us?” and Ban͠ggílît answered that he would remain four days. Then the people began to laugh and one of them said: “Not four days but four years here!” “Ha!” cried Ban͠ggílît, “I shall never do that! Wait until you see!” “Just so!” answered the other, “but one day here is the same as a year on the Earth World,” but Ban͠ggílît thought that he was lying.

Ban͠ggílît visited all of the towns there. He worked in the rice fields and they gave him four jars as his wages. Then his host said to him: “Return home now, for you have been here four days, which, according to the usage of the Earth World, are four years.” “Yes,” answered Ban͠ggílît, “I wish to go home now, as I am homesick for my family. You have been very good to me, for you have given me wages for my work.” And the host said: “It was a gift; not wages, but a gift, that I gave you,” and he led the way and pointed out to Ban͠ggílît a ladder. “Go down that ladder, and in a short time you will arrive at your house,” he said. Ban͠ggílît started to go down, but one of the jars struck heavily against the ladder and was broken. He went down the ladder and at last arrived in the top of a betel-nut tree. He slid down the trunk of the tree to the ground, and the chickens were crowing and it was just dawn. And he looked at his surroundings and exclaimed: “Why this is my own house!” His relatives came out and said: “Who are you?” and he replied: “This is my house.” They looked at him closely and cried: “Well now, it is Ban͠ggílît who has been gone these four years!” And they sat down and talked long together. He showed them the jars, and they asked: “Where did you get those?” And he answered: “I brought them from the Sky World,” and they were afraid and went to look for the ladder but it was no longer there.69

The above myth may well have been invented by some man who, unknown to his relatives and friends, wandered across [116]the mountains into Lepanto or Benguet and returned after four years with the jars in question. Hundreds of myths and legends of this type are current among the Ifugaos.

No representative collection of Philippine myths has yet been made, and the present paper can only be considered a beginning. I hope to be able to continue the work. [117]

1 Read before The Philippine Academy, October 2, 1912. The paper is intended as an introduction to a series of more complete studies in Philippine mythology and religion. ↑

2 A complete bibliography cannot be given within the limits of this paper, but a number of the most important printed titles and manuscripts have been cited. ↑

3 Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands. Cleveland (1906), 37; (1907), 48. ↑

4 This Journal (1906), 1, 812–818. Many plates illustrating Ilongot types and culture are given. ↑

5 The Philippine Islands and Their People. New York (1898), 362–434. ↑

6 A typewritten manuscript of 60 pages, entitled “The Hampán͠gan Man͠gyans of Mindoro” by Dr. Fletcher Gardner. U. S. A. (1905). In the records of the division of ethnology, Bureau of Science, Manila. ↑

7 This Journal, Sec. D (1912), 7, 135–156. ↑

9 Smithsonian Misc. Colls. (Paper No. 1700), 48, 514–558. ↑

11 I am informed by Dr. N. M. Saleeby that this myth is also known among the Malays of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. ↑

12 Kágbubátan͠g is a point within sight of the town of Placer, eastern Mindanao. ↑

13 The offering may be very small, even a little piece of wood, and is thrown overboard while passing the point. ↑

14 There is said to be a similar locality near Taganíto, eastern Mindanao. ↑

15 Bináoi is the name of an oddly shaped peak at the source of the River An͠gdánan, tributary of the River Wáwa, Agúsan Valley. ↑

16 Limes and lemons are said to be objects of fear to the búsao. ↑

17 Garvan suggests these stories as illustrations of punishment following the imitating or making fun of animals, acts which are strictly tabú in Manóbo culture. ↑

18 Some say that the spots upon the moon are a cluster of bamboos, others, that they are a baléte tree. ↑

19 Our information concerning these peoples is limited, but of much interest. Besides the work of Garvan, the chief sources are the Letters of the Jesuit Fathers and a paper on the Subánuns [Christie, Pub. P. I. Bur. Sci., Div. Ethnol. (1909), 6, pt. 1]. The latter does not record any myths, but gives several song-stories about great culture-heroes which throw much light on the character of the Subánun mythology and identify it with the mythologies of the other pagan tribes of Mindanao. These hero-stories are too long to be given here. ↑

20 The Tin͠ggiáns, or Itnegs, should be excepted, as there are important and accurate accounts of these people by Gironière, Reyes, Worcester, Cole, and others. ↑

21 According to the translation by James A. Robertson in Blair and Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1906), 33, 167–171. ↑

22 Note the similarity of this place-name to the Kágbubátan͠g of the Manóbo legend, p. 89. ↑

23 Translated by Roberto Laperal from “Igorrotes,” by Angel Perez. Manila (1902), 319–320. ↑

24 Jenks, Albert Ernest, The Bontoc Igorot, Pub. P. I. Ethnol. Surv. (1905), 1. ↑

25 Seidenadel, Carl Wilhelm, The First Grammar of the Language Spoken by the Bontoc Igorot, with a Vocabulary and Texts. The Open Court Publishing Co., Chicago (1909). ↑

26 Opus. cit., 485–510. Seidenadel gives an interlinear literal translation, which is, in some places, slightly inaccurate. I have made a new free translation directly from the Bontok. The text was told in the form of a story rather than that of a myth, and contains much extraneous matter which I have omitted. ↑