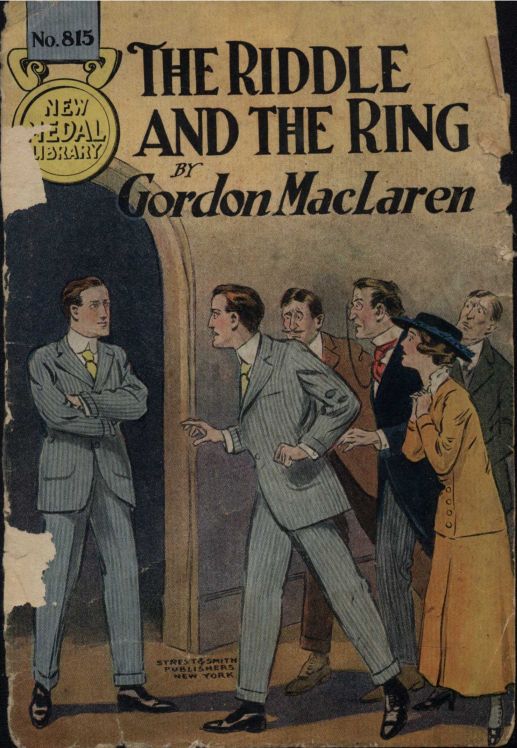

THE RIDDLE AND THE RING

The Riddle and the Ring;

OR,

WON BY NERVE

BY

GORDON MACLAREN

[From TOP-NOTCH MAGAZINE]

STREET & SMITH, PUBLISHERS

79-89 SEVENTH AVE., NEW YORK CITY

Copyright, 1911

By STREET & SMITH

The Riddle and the Ring

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages,

including the Scandinavian.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

THE RIDDLE AND THE RING.

CHAPTER I.

THE LITTLE MAN IN BLACK.

It was the second time the man had passed the bench, and, as their eyes met for an instant before the stranger swiftly averted his head and walked on, Barry Lawrence frowned with quick suspicion. Was it possible that the intolerable persecution had begun again? For more than three weeks he had been left in peace, and it seemed the irony of fate that now, at a moment when he was tasting the bitter dregs of life, the harassing should begin again.

The next moment he shrugged his shoulders resignedly. After all, what did it matter? They could get nothing from him now—he had nothing to give. If they had indeed returned, they must soon discover that.

The massive façade of the Pennsylvania Station had caught his eye, and brought new hope to his numbed brain. Here at least would be comparative warmth, and they could not very well turn him out. He could pretend that he was waiting for a train, and might sit for hours in the waiting room. After that—— Well, he did not wish to think of afterward.

He was only just beginning to recover from the stupefying cold which had numbed and chilled him to the marrow, and driven him into the great station to keep from dropping in the icy, wind-swept street.

He fancied that the passing porters looked at him curiously. When the announcer strolled near him, he felt impelled to turn toward the news stand in the corner. At least he could afford a paper. It was about the only thing he could buy now, and with it he could retire to the waiting room with some semblance of naturalness.

It was as he turned away from the stand that his eyes met, for the first time, those of the little man in black. Lawrence did not notice his appearance particularly then, but averted his eyes, and strode toward the men's waiting room. Here it was much warmer. The benches were well filled, but he found a seat facing the door, spread out his paper, and began to read.

Perhaps five minutes later he happened to glance up in time to see that same short, slim, precise figure pass the bench on which he sat. Of course, there might have been nothing more than a coincidence in it—people are constantly walking about a station while waiting for a train, and one frequently notices the same face half a dozen times in the space of a few minutes.

Still, Lawrence felt annoyed. His recent experience of having been followed and spied upon had so worn on his nerves that he constantly found himself suspicious of even the most casual glance. A frown furrowed his wide forehead, and, though his eyes dropped again to the printed sheet before him, he could not seem to dismiss the commonplace stranger from his mind.

Thus it happened that, when the man passed the bench again, Lawrence threw back his head swiftly, and caught the pale, grayish eyes fixed on his face with a stealthy, but unmistakably intent, scrutiny. The lids drooped instantly, and the stranger continued his pacing without a pause, Barry's glance followed him suspiciously.

This man did not look at all like the others who had made his life miserable for months. He seemed so insignificant, with his slight, spare form, his pale eyes, and rather weak face. He looked more like a bookkeeper or clerk, grown old and sedate in the service of some long-established banking house, than anything Lawrence could think of; though that did not seem to fit him exactly.

Now the man had turned and was coming back, and Barry, noticing his face intently, found himself wondering whether he was really old or not. After all, he might easily have been thirty-five or so; it was his iron-gray hair and curiously set expression which made him seem older.

The young fellow's eyes dropped to the paper, and he waited for the stranger to pass on. The latter did not pass, however. Instead, he approached the bench, and quietly took the seat on Barry's left. There was a momentary pause, during which Lawrence wondered what under the sun was coming next. Then the unknown cleared his throat, shot a quick glance at the stout man dozing at the end of the bench, and spoke.

"I beg pardon," he said sedately, "but would you have any objection to earning a thousand dollars?"

CHAPTER II.

AN AMAZING OFFER.

Lawrence dropped his paper, and flashed a startled, bewildered glance at the man beside him. For a moment he was silent, unable to credit his senses.

"What did you say?" he gasped at length.

"I asked if you would care to earn a thousand dollars," the stranger repeated, in a quiet, precise voice.

Lawrence stared for a second longer, and then suddenly burst into a harsh, mirthless laugh. For an instant he had been thrilled to the very core. A thousand dollars! Good Lord!

In that fleeting space there flashed through his brain a dozen pictures—clear, vivid, and distinct. He saw restaurants such as he used to patronize, with food—real food, and not the gross, coarse stuff one ate simply to fill that gnawing, aching void. He saw theaters, with their glittering lights and stirring music. He saw his old rooms, cheery and homelike in the lamplight and the red glow of the grate fire. He saw an overcoat, well cut, and lined with thick, warm fur, into which he might snuggle and defy the bitter blasts which had sapped his vitality and tortured him almost beyond endurance. He saw everything that a thousand dollars would bring to him.

And then he came to earth with a thud. Of course, the man was mad!

"I can understand that this may seem a little odd to you," the stranger went on, in that same dry, unemotional tone, "but the circumstances themselves are somewhat out of the ordinary. I had hoped that you might consider the matter favorably."

Something in the other's calm, sedate, business-like manner made Lawrence eye him again keenly. There was nothing in the least savoring of insanity about the stranger. His whole personality fairly exuded respectability. His pale eyes were quiet and steady—the eyes of a man who might be utterly unemotional and lacking imagination, but scarcely the eyes of a maniac.

Somehow the glance steadied Barry, and brought him new hope. After all, it would do no harm to inquire further into this extraordinary matter. He could scarcely be worse off than he was now.

"You can hardly blame me for being surprised," he said, with a faint, whimsical smile. "I beg your pardon for laughing, but I couldn't help it. If you will be a little more definite, and explain what I shall have to do to earn this money, I'll be very glad to consider it."

The stranger did not smile in answer. He simply nodded in a manner betokening his satisfaction, and turned more directly toward Lawrence.

"Good!" he said briefly, in that same low tone, which made it impossible for any passer-by to hear him. "The matter is very simple. It will take exactly one week of your time, at the end of which the thousand dollars I shall hand you now will be yours, without further obligation on your part."

"You mean to pay me in advance?" Lawrence exclaimed incredulously.

"I am obliged to. I think, however, that I may safely leave it to your honor to fulfill the conditions I impose."

Barry frowned. The situation was growing more and more puzzling, and verging on the absurd.

"And those conditions are?" he questioned.

"Simply this," the unknown explained: "If you accept my proposition, you will at once provide yourself with an ample wardrobe, including proper evening clothes—provided, of course, that you are not already so equipped."

Barry's lips twitched as he remembered that empty hall bedroom over near Tenth Avenue, but he made no comment save an understanding nod.

"There are shops where a man of taste can obtain these things ready-made," the stranger continued quietly. "I should prefer to have them cut by a good tailor, but there is no time. Having secured the wardrobe—you understand that there must be no stinting in either quality or quantity—I will give you an additional sum for expenses. You will go to the St. Albans Hotel, and engage a suite of rooms. You know the house?"

Lawrence shook his head. It seemed that he could not speak. His brain was whirling, and he was beginning to wonder whether it might not be he himself who had taken leave of his senses. One or the other of them must be mad; there could be no doubt of that.

"It is on Forty-fifth Street, just west of the avenue." The precise, matter-of-fact tone of his companion's voice penetrated to Barry's disordered brain, and again he felt that odd, reassuring sense he had noticed before. "A quiet, high-class house. You will remain there for just one week, beginning to-day. During that week you will dine every night at the Waldorf; lunch each day at the Plaza, the Knickerbocker, Shanley's, or restaurants of equal standing, and next Tuesday afternoon, at three o'clock, the thousand dollars will be earned."

Lawrence sat staring at him, open-mouthed, waiting for him to continue. When it became evident that the little man had nothing more to say, Barry's eyes threatened to pop out of his head.

"Is that all?" he managed to stammer.

"Yes."

"You don't want me to do anything but that?"

"No."

"He is daffy!" Lawrence said to himself decidedly. "There can't be a doubt of it. He's probably given his keeper the slip, and is having the time of his life with me."

For an instant his heart sank, for, in spite of everything, he had been thrilled by the prospect opened up by the stranger's words. Then he shrugged his shoulders. After all, it would be rather diverting to see how the fellow would get out of the affair, and Barry was sadly in need of something to take his mind from his own difficulties.

"My time, then, except for lunching and dining and sleeping, will be my own?" he inquired seriously.

"Exactly."

"You wish me to register at the St. Albans under my own name?"

"That's a matter for you to decide. It's quite immaterial to me."

"I suppose it would be a waste of time to inquire why you are willing to pay such a sum for anything so very simple," Lawrence remarked tentatively.

"Quite so!" the stranger returned emphatically. "That is altogether my affair. Well, what do you say?"

Barry kept his face serious with difficulty. "Say?" he repeated. "Why, I accept, of course. I'd be a fool not to."

The unknown arose briskly.

"Good!" he said. "Suppose we take a stroll outside. This place is getting close."

Without question, Lawrence followed him out into the great vaulted space. What was the fellow going to do? How was he going to escape carrying out his side of the bargain with any plausibility or grace? Of course, he would get out of it somehow, for he was mad—mad as a March hare.

But, in spite of this conviction, Barry felt the blood tingling in his finger tips as they walked past the news stand, past the ticket offices, and on to the deserted extremity of the enormous marble hall.

CHAPTER III.

PANIC.

Clear of the last passer-by, the little man paused, and thrust one hand into the pocket of his inner coat. "There is one other condition," he said, drawing out a thick leather wallet. "Under no circumstances must you explain to any one where you obtained this money. You must be silent regarding every particular of our meeting here, and the terms of our bargain. I have your promise?"

Lawrence, his eyes fixed incredulously on the bulging wallet, felt something grip his throat. It could not be true—it simply could not! And yet——

"I promise," he said, in a queer, hoarse voice.

The stranger opened the leather flap, and showed the wallet crammed with crisp bank notes.

"I have your word to carry out faithfully every condition I have mentioned?" he questioned briskly, fixing Barry with a keen glance.

The latter tore his eyes from the bills, and returned the look.

"I give you—my word—of honor," he stammered.

His brain was whirling. He could not believe his senses. It was all a mad illusion—a dream from which he must soon awake. His heart, thudding loudly and unevenly, drove the blood into his face, a crimson flood. He was trembling, but not with cold. The stranger's voice seemed to come from far, far away; it had fallen to a mere whisper, which Lawrence could barely catch.

"There is a matter of another thousand dollars here for expenses," he was saying. He held out the wallet, and Barry's fingers closed around it instinctively. "That is all, I think. You know what you are to do, and I can trust to your word of honor."

Without another word, he turned and walked away.

Lawrence sprang after him. "I haven't thanked you!" he exclaimed incoherently. "You don't know—what you have done for me. I—I——"

"I want no thanks," the stranger returned impatiently, his eyes fixed on the great clock. "You can best show your gratitude by carrying out my conditions to the letter. I am pressed for time. I can wait no longer. Good-by!"

As he hurried away, Lawrence stood staring after him, as if in a dream. He saw the slim, somberly clad figure bustle past the waiting rooms and through the doors into the train shed. A moment later the announcer bellowed out the last call for a certain train, and his raucous voice aroused Barry from the trance.

He had thrust the wallet into his pocket, but now he took it out, and opened it with trembling fingers. The bills were still there—new, crisp, and yellow. His fingers touched them, and they did not crumble into dust, as he almost expected them to do. Scraps of long-forgotten fairy stories, read as a child, danced through his dazed brain, in which benefactors in strange guises gave unexpected largess to starving, freezing people. Nothing could be stranger than the appearance of the little man in black.

He laughed aloud. Then a thought came to him which swept the smile from his lips and the color from his cheeks in the twinkling of an eye: The bills were counterfeit!

With blanched face and trembling fingers, he thrust the wallet back into his pocket like a flash. What a fool he had been—what a bonehead! The bills were counterfeit, and the stranger, followed closely, no doubt, by detectives, had taken this way of getting them off his person. This accounted for the stealth, the secrecy, of the transaction. This explained everything which had been inexplicable.

With a swift-drawn breath, Lawrence looked nervously around, to meet the glance of a thin, wiry man standing in the center of the rotunda. Cold chills began to course up and down Barry's spine. What should he do if he were caught with the stuff in his pocket? If he could only escape from the station there might be a chance of throwing it away unobserved. If only he had not dropped his paper, he might, even here, tuck the incriminating wallet in its folds, and fling both carelessly into the rubbish can. What a fool he had been!

Presently the man who had been watching him turned slowly away, and walked toward one of the ticket windows. That was only a pretense, of course. Lawrence realized that perfectly, and yet, relieved of the stranger's scrutiny, he ventured to move toward the broad flight of steps leading up to that long corridor, and thence to the street.

The man did not turn, and Barry's speed increased. If he could only get out of the station it would be all right. As his foot struck the bottom step, his eyes, glancing backward, told him that the man was buying a ticket. He could scarcely see through the back of his head. Perhaps there was a slim chance, after all.

Less than a minute later he flung himself out into the icy street, with a gasp of thanksgiving. Hurrying past the long front of the building, it seemed to him that every one must be staring after him. Through his thin coat the wallet bulged horribly. How could any one fail to guess what was in it?

Under normal conditions he was not a fellow to act in this fashion, but conditions were far from normal. He was half starved, and half frozen. He had lost his job four months before, under circumstances which made it almost impossible to get another, and he was desperate. On top of this, the extraordinary situation in which he found himself was enough to make any man lose his head.

But Lawrence did not quite do that.

He was flustered, nervous, almost terrified; but through it all he clung to one idea—to get back to his miserable room he had thought never to see again. There, at least, he would have security for the moment, and a chance to pull himself together.

So he sped on, dodging through cross streets and down wide avenues, the wind whistling in his ears unheeded, the cold penetrating anew his flimsy garments. As block after block was set behind him without the expected happening, a shaky sort of confidence began to take possession of him. And when at last he ran up the steps of the dilapidated rooming house on Twenty-fourth Street, he gave a long sigh of relief.

"I'm glad I didn't throw it away, after all," he muttered, feeling for his key with fingers blue with cold. "There's just a chance it may be good."

But in his heart he felt that the chance was slim indeed.

CHAPTER IV.

THE EMERALD RING.

In the absorption of the greater trouble, Lawrence had quite forgotten one of his lesser worries—his landlady. That argus-eyed female was on the watch, however, and darted up from the basement just in time to catch him in the hall.

"I s'pose you're comin' to pay me the three weeks' rent you're owin'?" she said, with sarcasm.

Lawrence winced at her tone. He was not yet hardened to that sort of a thing.

"I hope to have it for you this afternoon, Mrs. Kerr," he returned quietly.

"You hope, do you?" shrilled the woman caustically. "Well, let me tell you right here, I ain't livin' on hopes. If that money ain't paid down by three o'clock, out you go. I don't care if it is below zero. I've stood your triflin' long enough, an' if you can't pay you can beat it an' find another lodging place. I hear they're letting loafers sleep in the churches these nights. That might suit you, bein' it's free."

Barry's face flushed, and his hand strayed toward the wallet in his pocket. For a second he was sorely tempted to hand her one of those crisp twenties, and tell her to keep the change. She would never find out its worthlessness until he was safe away. He stifled the impulse, however, and, repeating briefly that she should have her money that afternoon, passed on up the stairs.

The instant his door was shut and the key turned, he jerked the wallet out and opened it with trembling fingers. As he shook out the mass of yellowbacks on the bed, the sight of them was like a stab of a knife. They looked so real it seemed impossible that they could be counterfeit.

He took up a fifty, and, carrying it to the light, examined it closely, feeling the texture and scrutinizing every little detail with care. He could see nothing wrong about it. Four months before, had such a bill been offered him at the bank, he would have accepted it without hesitation.

He took up another, which seemed equally good. He examined half a dozen without finding a single flaw, and then decided that the trouble was in himself. His judgment was no longer what it had been, and he dared not trust it.

"They look good, but they can't be," he muttered, frowning down at the beautiful bits of yellow paper strewn so carelessly over the bed. "What the mischief can I do?"

For fully ten minutes he stood there, his eyes thoughtful and his forehead wrinkled. Then, gathering the bills up, he put them all back in the wallet save one, a ten; after which he lifted the mattress, and shoved the wallet well underneath it.

"There!" he said, straightening up; "now, if I'm pinched, they won't find but one on me. I hate to take this over to the bank, but that's the only way I can be sure."

Ten minutes later he entered the big Twenty-third Street National Bank, and walked directly to one of the tellers.

"Will you kindly tell me if this is all right?" he said quietly, thrusting the ten-dollar bill through the window.

The teller picked it up, and examined it intently. Then he glanced keenly and with some suspicion at Lawrence.

The latter bore the scrutiny well, however, and the official looked the bill over carefully again, drew it through his fingers, and finally tossed it back.

"Certainly it's good," he said, rather brusquely. "What made you think it wasn't?"

For a second Barry was silent. He could not have spoken to save his life. Then he stammered something about "just wanting to make sure," and turned away, quite heedless of the impatient exclamation of the teller at having his time wasted in that manner.

Lawrence had no distinct recollection of how he got back to his room. His brain was in a whirl, and the only thing which stood out vivid and clean-cut was the realization that the money was real.

Real! Ye gods! The thought intoxicated him like champagne. He forgot the cold and wind, his thin clothes, his ravenous hunger. He gave no thought to who the donor might be, or how he had acquired those crisp yellow bills. They were his, every one of them. All he had to do was to buy clothes, to take an apartment at the St. Albans, to dine for a week at the Waldorf! He laughed aloud, and a shivering, frosty-nosed citizen turned and stared after him suspiciously as he hurried down the street.

Lawrence did not see this; nor, seeing, would he have cared. He flew through the snowy streets, and on the doorstep of his lodging house was smitten with a sudden fear for the safety of his treasure. Racing up the two flights of stairs, he darted into his room and tore up the mattress.

The wallet was safe, but what might have been made him tingle all over with a sickening sensation, for he had gone out without even locking his door.

Having turned the key, he sat down on the bed, and opened the wallet. Slowly, deliberately, and with a delicious thrill, he counted the bills. There were fifteen one hundreds, eight fifties, and an odd hundred dollars in twenties and tens.

Evidently the little man in black had been prepared for his acceptance of the extraordinary offer, and the realization brought into Lawrence's mind a swift wonder as to what it could all be about. What reason—what possible reason—could the stranger have for making those astonishing, seemingly absurd, conditions? What purpose would be accomplished by Barry's appearing at the places mentioned for the short space of a week?

Urged on by a fresh curiosity, Lawrence took up the wallet again, to examine it for some mark of identification.

It was of heavy pigskin, finely made, and bearing the stamp of a well-known English firm. That much told nothing; but, in turning it over, Barry noticed something which had escaped his attention before. One corner was bulkier than the rest. His inquiring fingers told him that there was undoubtedly a hard object in one of the numerous compartments of the case.

Eagerly he searched, and at last, slipping his fingers into a slit in the back of the wallet, drew forth a ring.

For a moment he sat staring at it in wonder and admiration, for it was one of the strangest jewels he had ever seen.

A great, square-cut emerald was in the center, and twined about it were two serpents in dull, exquisitely chiseled gold, with tiny flecks of emerald for their eyes. Their heads were slightly raised, and the unknown craftsman had wrought them in amazing similitude to life. With patient cunning he had carved each tiny line of flat, broad head and sinuous, undulating body, until it seemed to Barry as if the things must actually wriggle presently, and dart out forked tongues.

"By Jove!" Lawrence exclaimed aloud. "I never saw anything like it in all my life. That emerald's a perfect whopper, and must be worth a fortune. He forgot to take it out, of course; and, hang it all, I don't see how the mischief I can get it back to him. I don't even know his name."

He slipped it on his finger, and found that it fitted well. Then, as he sat admiring its perfect, almost uncanny, beauty, the thought flashed into his mind that, by its means, he might solve the mystery of the man in black.

"Of course he'll come for it," he thought. "I have only to keep it, and he'll show up before long to claim it. Then perhaps I'll find out something."

He began to gather up the bills and stow them carefully away, his fingers trembling with excitement. There was much to be done if he were to carry out the stranger's conditions.

CHAPTER V.

THE POWER OF AVARICE.

In the hall of the lodging house, Lawrence stood by the door, holding a crisp yellowback in his hand. Mrs. Kerr was panting up the basement stairs, from which came the odor of cooking cabbage to join the ghosts of a thousand boiled dinners that lingered in the stuffy, airless place.

Barry was not yet used to it. He felt stifled, breathless, almost nauseated, and he longed to get away. He did not look at the ferretlike face of the slovenly woman as he handed her the bill. There was something about her he could not abide.

"Here's your money," he said brusquely. "I am leaving at once."

She grasped the bill, and examined it closely. Then she flashed a swift, sidelong glance at Lawrence. There was something about his face and bearing which she had never seen before, and it aroused her curiosity.

"I ain't got a bit of change in the house," she said, in a very different tone from the one she had used an hour before. "Mebbe you want it to count on this week."

Barry's fingers had closed around the knob.

"You can keep the change," he returned shortly. "I said I was leaving at once. I am not coming back."

"Lord save us!" she gasped. "Don't say that, Mr. Lawrence. Don't say as you're leavin' on account of them hasty words I spoke this mornin'. Fergit it. I'm a lonely widder woman as has to work my fingers to the bone to make both ends meet." Her voice took on a whining tone. "I has to count every penny, an' sometimes I'm most distracted, an' says what I don't mean. You——"

She broke off abruptly as the door slammed, and instantly a venomous expression leaped into her face. Like a flash, she had yanked the door open, and run out on the little stoop, to peer around the corner.

For a moment or two she stood shivering in the cold, her small, close-set eyes fixed intently on the back of the man hurrying toward Ninth Avenue. When he had disappeared she came back into the hall, her face thoughtful.

"Now, what's come to him, I wonder," she muttered, making her way slowly back to the basement stairs. "It's somethin', I'll be bound. I never seen him look that way before. He was excited, too, when he come in before. If I'd had any sense I'd 'a' looked around his room whilst he was out."

An instant later she was pounding up the stairs to the top floor. The door of the hall bedroom was ajar, and, pushing it open, she walked in. For a moment she stood there, her sharp eyes taking in every detail of the miserable place. The scantily covered bed showed signs of having been sat upon, but that was nothing unusual. Most of Mrs. Kerr's lodgers found the bed more comfortable than the straight, hard chair she supplied. The woman noticed something else, however, which brought a swift frown to her face, and made her step quickly forward, and jerk up the cornhusk mattress.

"He's been hiding something away here," she snapped aloud, peering closely at the rusty springs. "I knowed it! What a fool I was not to look before! but who'd 'a' thought it, after the times I've went through his——"

She broke off with a queer, choking sound, and in a second every trace of color had left her face. For a moment she stood as if turned to stone, staring at the floor with a look of utter incredulity in her narrowed eyes. Then, with a guttural sound, half groan, half exclamation of joy, she dropped on her knees and snatched up a crisp twenty-dollar bill that lay under the bed.

"Good Lord!" she gasped.

Stumbling to her feet, she held it out, devouring it with her eyes. Then, fumbling in her dress, she drew forth the money Lawrence had just given her, and compared the two. Both were crisp and new and yellow; both were uncreased, as if they had lain together in the same long wallet or package. And Mrs. Kerr's eyes lit up with a horrible sort of cupidity.

"An' I let him go!" she muttered, through clenched teeth. "I let him step out of the house with his pockets full of dough, leaving a twenty behind he never knowed he'd lost! I'm a dope! But mebbe it ain't too late. Mebbe—— Jim! Jim!"

Her face flushed and mottled, her hands trembling, she flung herself into the hall and down the stairs, calling the name at intervals.

She had reached the second floor, and was panting toward a door in the rear, when it was jerked open, and a man appeared on the threshold.

"Shut your face, you fool!" he snarled. "What're you yowling round like that for? You'll bust yer pipes!"

She caught her breath with a queer gurgle, and, putting out both hands, pushed him back into the room.

"Wait till you see what I found," she gasped. "Wait till you hear——"

Then the door slammed shut, and the sound of her voice ceased abruptly, leaving the hall dark and silent, save only for the rapid, indistinct murmur rising and falling in the room beyond.

CHAPTER VI.

AS IN A DREAM.

It was not until he had reached Broadway that Lawrence remembered his failure to turn over the latchkey before leaving the miserable lodgings for good. For a moment he hesitated, wondering whether he ought to go back. Then he remembered the extra money he had given the woman, and the small cost of a new key.

"She can get another for a quarter," he murmured. "Besides, I simply couldn't go back there now. I wonder I was able to stand the old harridan as long as I did."

Dismissing the matter from his mind, he turned down Broadway, and a few minutes later entered the big clothing store of Butler & Bloss.

"I wish to look at some fur-lined coats," he said quietly to the gray-haired man who stepped up to him.

Whatever surprise the latter may have felt at this request from a man wearing no overcoat at all, and a thinnish suit, at that, none showed in his face. Besides looking the gentleman, Barry had an undeniable air about him which commanded respect. No doubt he might have stepped in from some near-by building without stopping to put on his overcoat. At any rate, the customer had the appearance of one used to instant consideration, so a salesman was summoned without delay, and Barry was committed to his care.

Lawrence had decided that about five hundred dollars of the expense sum should be reserved for hotel, restaurants, and incidentals. The remainder, therefore, was left to be spent on his wardrobe, for he had determined to carry out the conditions of the strange bargain to the very letter.

For a full hour he was busy in the various departments of Butler & Bloss, and though in that time he ran up a bill of close on to four hundred dollars, the fur-lined coat was his only extravagance. Even that was not expensive, as such things go, but he had been so cold for so many days that he could not resist the handsome garment, with its luxurious lining and wide collar of unplucked otter.

In addition to this, he bought another, lighter overcoat, of soft dark cheviot, two sack suits, and a Tuxedo. There were also, of course, several pairs of shoes necessary, shirts of various sorts, collars, neckties, underwear, gloves, and a quantity of various odds and ends, which added materially to the total of the bill. When he had paid it, and ordered the things delivered at the St. Albans before six o'clock, he slipped into the fur coat, drew on a new pair of gloves, and went out into the street.

There he did not hesitate an instant, but made a bee line for the nearest Broadway restaurant. The interest and excitement of spending money after such a long deprivation had kept him from realizing how ravenously hungry he was, but at the first lull the fact smote him with renewed force.

The glamour of that first real meal in weeks will linger long in the memory of Barry Lawrence. He ordered lavishly, luxuriously, and yet with the instinctive good taste which had characterized him in the days when that sort of thing was a part of his regular life. And, as the courses followed one another, he ate slowly, enjoying every mouthful, reveling in the hum and buzz of conversation, the animated faces of the people about him, and the plaintive murmur of violins playing the latest popular airs.

It was during the progress of the meal that he suddenly solved the problem of the evening clothes which had been troubling him. A dress suit had always seemed to him the one thing it was impossible to get ready-made, and for that reason he had refrained from looking at them in the shop. A sudden remembrance came to him, of the suit which Tyson, his tailor, up on Thirty-eighth Street, had been making for him when the crash came. He had never shown up for the final fitting, and it was just possible that the man had held the garments, awaiting some word from him.

Having paid his bill and left the restaurant, Barry walked through to Fifth Avenue and turned up that thoroughfare toward the tailor's rooms. One might have supposed he would have taken a stage or taxi, but no such thought entered his head. Walking, when one is well fed and well clothed, is a very different thing from the exhausting struggle of that morning, when the cold seemed to freeze his very marrow.

He reveled in the warm comfort of his fur-lined coat and heavy deerskin gloves. The passing crowd pleased him, and the very contents of the shop windows interested him as they had never done when he had been penniless. There were few things among the myriads displayed in such tempting array which he could not step in and buy if he chose. The fact that he did not choose made no difference whatever.

Past the brick façade of the Waldorf he walked briskly, glancing in at the dining-room windows with a smile. He would dine there later. It was a pleasant thought.

The tailor welcomed him heartily, gave the suit of evening clothes a final fitting, and promised to have it completed and delivered at the St. Albans by evening.

Presently Lawrence crossed the avenue, and purchased a handsome stick. A little farther on he remembered the need of cuff links and studs. A firm of famed goldsmiths was near at hand, and without hesitation Barry entered.

As the tray of cuff links was lifted out and set on the glass case, Lawrence naturally stripped off his gloves to examine the articles more closely. He gave no thought to the fact that the serpent ring was still on his finger, where he had placed it for safe-keeping, but he was speedily reminded of its presence there by the behavior of the salesman.

The man could scarcely keep his eyes off it. He stared and stared, fidgeted about, and stared again. Finally, unable to contain himself longer, he spoke.

"I beg your pardon, sir," he said, in a quick, nervous manner, "but you have a wonderful ring there."

Lawrence did not lift his eyes from the tray.

"I think it rather good myself," he admitted.

His tone was intended to quell this unwelcome display of interest, but it quite failed of its effect.

"I have never seen anything like it before," the salesman went on rapidly. "Would you mind if I—looked at it more closely?"

Barry glanced up with a faint frown, alert for the hidden meaning in the man's words. What he saw reassured him. The wide brow, the vibrant, tapering fingers—above all, the soft brown eyes, shining with enthusiastic interest—all pointed toward an expert in his line, to whom a thing of beauty was a source of joy, no matter where he found it.

Without a word, Lawrence extended his hand, and the salesman bent over it, his eyes devouring the ring.

"Extraordinary!" he murmured, half to himself. "The stone is perfect, and worth a small fortune, but the workmanship is even more unusual." He sighed a little, and went on in a rapt tone: "Eastern, of course. Probably Indian, but not the stuff they make there now. I should place it in the reign of Shah Jahan, the golden age of Delhi—over three hundred years ago. But of course you know all this. I must beg your pardon for letting my interest get the better of me."

"You needn't," Barry returned. "I am very glad to know what you have told me. The former owner of the ring gave me little or no information of its history."

Having, concluded his purchases, to which he added a silver cigarette case, he continued his walk up the avenue in a rather thoughtful mood.

So the ring had come from India! Still, that proved nothing. He could not picture the little man in black having anything to do with that country, and it did not really follow that he had. No doubt the emerald had passed through numberless hands since leaving the loving fingers of its creator.

It was foolish to waste time puzzling over a problem the solution of which was beyond his reach. Besides, Lawrence had a curious feeling of irresponsibility, a conviction that he was in the hands of fate. What was to be, would be. There was nothing left for him to do but float with the current. Since that current promised at the moment to take him into pleasant places, he made no effort to struggle out of it, or swim away.

CHAPTER VII.

NEW GRACE AND DIGNITY.

It was half past six, and Lawrence stood in the bedroom of his attractive suite, taking a last critical look at his reflection in the long mirror.

Mrs. Kerr would scarcely have recognized in that tall, distinguished figure in evening dress her former lodger. Somehow, it was not the clothes alone which made the difference, though they had, of course, much to do with it. Few men there are who do not feel the influence of well-cut, perfectly fitting evening clothes.

With Barry, however, the transformation was something deeper and far more encompassing. His face seemed actually fuller, and it glowed with color. His eyes sparkled with excitement. He carried himself with a new grace and dignity. His whole expression was that of a man in love with life, and determined to extract from it the last drop of enjoyment.

Naturally he was quite unconscious of all this as he stared into the glass. He was occupied in noting the fit of the coat about his broad shoulders, and the effect of the barber's shears upon his wavy blond crop. Both seemed satisfactory.

"Tyson never did a better piece of work in his life," he said aloud, with satisfaction.

Turning from the glass, he reached for his fur-lined coat, and slipped it on. The room was cluttered with parcels and boxes, opened and unopened. Clothes were strewn over bed and chairs. It was too late now to put them away. He could do that later.

Taking up the pigskin wallet from the dressing table, he extracted a hundred dollars, and slipped the bills into an inner pocket. Downstairs he handed the wallet to the clerk, asking him to put it into the safe, and sallied forth to where a taxi waited by the curb.

The corridors of the Waldorf were agleam with lights, and resounded with a buzz of talk, the swish of skirts and gay laughter of pretty women, not a few of whom turned for a second glance at Lawrence as he made his way slowly to the dining room.

Here the head waiter met him, and ushered him deferentially to the table which had been reserved by telephone. Another man, deft and silent-footed, took his order.

Barry leaned back with a barely perceptible sigh of pleasure. It was good to be back in his own world again; good to watch the many faces, with their swiftly varying expressions, to hear the chance remarks that filtered to his ears through the soft music from the orchestra.

Resolutely he thrust all thought of the future from his mind. There were to be six more nights like this, and when the last one had passed it would be quite time to turn to serious things.

The oysters had passed, and the soup. Barry was just finishing his entrée when, happening to glance around at a table standing somewhat back of him and on his right, he experienced a shock.

Two men were dining there alone. The one who faced him, and whose expression was almost ludicrous in its mixture of startled surprise and outraged anger, was short and stout and rather pompous. He was Robert Tappin, president of the Beekman Trust Company. His companion, black-haired and ruddy-cheeked, with full lips, and the blue tinge of a heavy beard showing on his clean-shaven face, was Julian Farr, the cashier.

Lawrence disliked them both with the intensity which only a man can feel for those who have wronged him deeply. A little over four months before he had been one of the tellers in that institution. A defalcation was discovered. Several thousand dollars was missing from the cash, and Barry was accused of theft. There was no real proof against him, but the money had been in his charge; and, though Lawrence vehemently protested his innocence, he was summarily discharged.

Not only that, but for weeks he had been followed by detectives set on by Tappin for the purpose apparently of finding out what he had done with the loot. Day and night they dogged his footsteps. Half a dozen times Barry had landed a position, only to lose it the next day, certain that these men had gone to his new employers with their lying tale.

Now these two who had nearly wrecked his life must turn up here to spoil his new-found pleasure. With sudden fierce determination, Lawrence resolved that they should not. Pulling himself together, he met Tappin's amazed look with a cool stare of utter blankness which staggered the man. Then he turned back and went on composedly with his dinner.

It was impossible to forget them, however. Though he did not turn again, he felt that their eyes were fixed upon him, and he knew as surely as if he had heard the whispered words that they were talking about him.

Nevertheless, he finished his meal leisurely. When the check had been paid, he arose and made his way slowly toward the door, without a backward glance.

His preoccupation prevented his noticing a rather odd incident which happened on his way out. Near the door, sitting alone at a small table, was a short, thickset man of forty odd, with a rather full, round face, helped out to some degree by a pointed Vandyke beard, tinged with gray.

During the progress of the meal he had been not a little interested in Lawrence, if one could judge by the frequent keen glances he shot across the room. But now, as Barry came toward him, he swiftly dropped his head, seemingly absorbed in the menu which lay before him. Not until the younger man had disappeared did he raise his eyes, and then a close observer might have noticed in them a curious, enigmatic expression.

Within three minutes the table by the door was empty.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE GATES OF CHANCE.

At the Fifth Avenue corner Lawrence paused, leaning on his stick, and glancing up and down the brilliant thoroughfare. Though it was too late for the theater, the night was still young, and he was wondering just how he would put in the hours before bedtime.

In the old days, before his disgrace, he would have headed straight for the Harvard Club, on Forty-fourth Street, and been sure of a pleasant, lazy evening; but now the thought did not appeal to him. In some ways Barry was unusually sensitive, and it had happened that the few acquaintances he encountered shortly after leaving the bank seemed cool and offish in their manner.

Whether that was really so, and chance had thrown the caddishly inclined in his way, or whether he had simply imagined it all, did not matter now. The result had been to embitter the young man, and make him determined to take no further chances of snubbing from those he had supposed his friends.

The club was, therefore, impossible. It was equally out of the question to look up any one else he had known in his prosperous days. As for relatives—well, Barry was singularly deficient in that respect. Save some cousins in Boston, and an aunt living in Providence, he was quite alone in the world.

In spite of this, the pause at the corner was not a long one. Lawrence wanted to walk. The fascination of the great city still held him in a vise. The novelty of seeing it in this wonderful new light had not even begun to wear off. He wanted to watch the people, look into the shop windows, smoke his cigar, secure in the knowledge that he was safe against cold and hunger and distress.

Wondering which way to turn, Barry's eyes fell upon an approaching Thirty-fourth Street car, and whimsically he determined to take the opposite direction to that of the first alighting passenger. With a faint smile curving his sensitive mouth, and lurking in the pleasant gray eyes, he saw a man bustle off the front platform, dart across the tracks, and hurry on up the avenue. Then, without hesitation, Lawrence wheeled about, and walked briskly downtown.

There was a certain fascination in walking thus at random, having no fixed plan, no definite destination. He had done exactly the same thing in the weary weeks which now seemed so dim and nebulous and far away; but this was quite different. He was well fed and immaculately garbed. There was money in his pockets, and a fine cigar between his teeth. When he tired of rambling he had simply to hail a taxi or step on a car and be whirled back to the luxurious apartment which belonged to him—for a week, at least.

And so it pleased him to feel again that he was in the hands of fate; that the gates of chance had opened to his touch, admitting him to a strange, fantastic city where anything might happen, and nothing was beyond the bounds of probability.

As he walked briskly southward, he amused himself for a time by watching the passers-by, and inventing stories to fit their appearance. But this soon palled. They were all so bundled up, and hurried past so swiftly through the bitter air, that all Barry could think of was how cold they were and how anxious to get home.

Then he took to regulating his course by means of odd devices. If a certain man crossed the avenue at Twenty-eighth Street, he would follow the example. If the next kept on downtown, Lawrence would turn eastward on Twenty-seventh Street, and the like.

It happened that the man turned into the side street, and Barry continued straight ahead until, high above the icy branches of the naked trees, the glittering Metropolitan Tower, ethereal and fairylike, in spite of its colossal bulk, loomed before his eyes.

He paused an instant, while the silvery chimes rang out the hour of nine. There were many directions in which he might turn his steps, but at the moment the square seemed singularly deserted. At length his glance shifted to the bright, open space beyond him, where three streets joined, and he smiled.

"If that Broadway car is a Lexington," he murmured, "I'll cut across the square."

The car approached, swerved off, and turned east on Twenty-third Street; and Lawrence promptly wheeled into the winding walk, and briskly followed the diagonal course.

The benches, usually so full of loungers, were deserted now. The fountain in the center was filled with dingy snow, while ice glittered on the iron railing about it. The wind, whistling across the open space, penetrated even the thick fur of Barry's coat a little, and made him half wish that guiding street car had not led him thither. He did not turn back, however; he was too much interested in this game of chance to give it up just because it had so far failed to bring him anything out of the ordinary.

Rounding the desolate fountain, he slipped on a treacherous bit of ice. When he recovered his equilibrium, he saw that a woman was coming toward him along the cement path. She walked hurriedly, yet there was an odd touch of indecision in her movements which puzzled Barry.

As they approached each other, she passed under the glare of an electric light, and Lawrence noticed for the first time how slim and girlish she was. She seemed little more than a child. Certainly she ought not to be on the streets at that hour and in such bitter weather.

As she came nearer he saw that she had no muff or neck-piece, and that her little suit seemed woefully inadequate. Her face was invisible under the wide brim of the black hat, but she did not pause or falter or even glance up at him.

Then came a sound which turned Barry's sigh into a quick gasp of pain, and made him whirl around to stare after the slight, retreating figure. It was a stifled sob, carried to his ears by the vagrant wind, until it seemed as clear and pitiful as if she had stood close beside him. Another followed, and another still. The girl was crying as if her heart would break.

CHAPTER IX.

A WOMAN IN DISTRESS.

For a second Lawrence stood rooted to the pavement. His first impulse was to follow her. She was in trouble, and perhaps he could help her. He took a few quick steps back toward the fountain, and stopped still. How could he speak to her? How could he offer to do her a service? She would misconstrue his motives, and be terrified. She would——

A faint cry, which was little more than a startled exclamation of terror, cut short Barry's mental reasonings, and in a second he was running forward with long, lithe strides. As he approached the fountain he saw another figure scurrying away across the snow toward Madison Avenue. The girl was crouching against the ice-covered railing, steadying herself with one small, gloved hand, and, as Lawrence came straight toward her, he saw that she was trembling violently.

"You called me," he said quietly.

For a second she made no response. Her fingers still clutched the iron railing; her whole attitude was that of one driven into a corner and standing at bay. From under the shadowy hat brim Barry could see that her lips were pressed tightly together. Her eyes, wide with a desperate sort of fear, were fixed upon his face.

"I heard you call out," Barry said gently. "I thought you were frightened at something."

Something in his voice, or perhaps his face—the light was very bright around the snowy fountain—reassured her. Her eyes lost a little of that look of terror, and her fingers relaxed their grip on the iron railing.

"I was," she answered, in a low, uneven, and charming voice, "terribly frightened. That—man——"

Suddenly she put up both hands to her face, and swiftly turned from him. Scarcely a sound came from her, but the sight of that bowed head and the convulsively heaving shoulders, showing but too plainly through the thin cloth of her short coat, hurt Lawrence desperately, and brought a lump into his throat. She seemed so young and frail and girlish, so utterly unfitted to cope with the world, that a quick impulse came to the man to take her in his arms and comfort her exactly as one does a child. He realized instantly, of course, that such a thing would be impossible.

"Please don't," he said softly, after a moment's silence. "It's all right now." He watched her trembling hands searching for a handkerchief, and then he went on, with deliberately forced cheerfulness: "I tell you what we'll do. If you'll let me, I'll walk along with you, so there won't be a chance of anything like this happening again."

She ceased dabbing her eyes, and, turning slowly, looked long and searchingly into his face. "You are very kind," she said at length, and Barry caught again that faint, Southern intonation which he had not been quite sure of before; "but it is a long distance, and I think I can manage by myself. I—am used to going about alone."

"But you really wouldn't be taking me out of my way—if that's what you were thinking," Lawrence expostulated. "I haven't a thing to do. I'm out for a walk, and one direction is just as good as another for me. I hate to think of your taking any more chances."

For a second the girl hesitated. Then her lids drooped a little, and she swayed the least bit, putting out one hand blindly to steady herself against the railing.

Barry stepped swiftly forward, and took her arm.

"Come!" he said, with a whimsical sort of positiveness. "You really must! I know it's unconventional, and all that, but we'll probably never see each other after to-night. I'll leave you wherever you wish, and say good night. You were heading toward Broadway, weren't you? Well, we'll go together."

The girl made no protest. Perhaps it was because she had come to the end of her rope, and had no strength left. Perhaps she sensed intuitively the motives which governed this frank, straightforward stranger who had come to her aid so opportunely. At all events, she let her hand rest upon his arm, and walked with him back through the square, across Twenty-fifth Street, into the dazzling stretch of Broadway.

The touch of her hand brought again to Barry that odd desire to protect and comfort her. By this time he knew that she was almost perishing with cold. In spite of her effort to control herself, he felt she was shaking violently, and every now and then the unconscious weight of her hand on his arm made him wonder whether some other thing than cold had not contributed to her weakness.

He wanted desperately to do something, yet somehow he could not think of any way. He had not asked her where she wished to go, and the girl herself volunteered nothing.

And so they walked on up New York's great artery, he talking carelessly, lightly, and frequently at random as his brain worked in another totally different direction, she answering him briefly now and then in her soft, tired voice, but more often silent—out of sheer weariness, he guessed.

Suddenly the electric sign of a well-known restaurant blazing before his eyes gave Lawrence the clew he had been seeking, and he stopped abruptly.

"Are you in very much of a hurry?" he asked.

She glanced up at him swiftly, and he was struck anew by the charm of her-wonderful eyes, the delicate beauty of her mouth and chin.

"Not very," she said, in an odd, restrained tone. "Why?"

"I was wondering whether you'd do me a favor," Barry returned glibly. "I meant to get a bite of supper here, and I hate to eat alone. If you'd only take pity on me, and keep me company, I'd be everlastingly obliged. After that we can take a car to where you're going, so's to make up time."

Again she sent a long, searching glance into his candid, level gray eyes. Then suddenly she laughed, a curious laugh, which had no mirth in it, but rather held an undercurrent of intense pathos.

"Very well," she said quietly, with an odd gesture of her hands.

Her manner brought the color into Barry's cheeks, and made him wonder whether she saw through his clumsy subterfuge. He did not hesitate, however, but stood aside for her to enter the turnstile door, following close behind.

The dining room was almost empty, for it was the quiet interval which comes between dinner and the after-theater supper crowd. They were ushered at once to a table against the wall.

While Barry was slipping out of his coat he noticed the girl glancing into a mirror beside her, touching her hair here and there, and giving the frilly lace thing at her neck an unconscious pat. She was still shaking a little, and when she drew off her gloves he saw that she was gently chafing her hands together beneath the shelter of the white cloth.

Her hair was brown, thick, and dark, with glints of copper in it, and waved attractively above her brow. Her eyes were almost of the same shade, with long, curling lashes, which made them seem almost too large for the delicate, oval face. Her mouth was sensitive, and infinitely appealing with its pathetic downward droop at the corners. There was an unmistakable refinement in everything about her; and, in spite of the fact that she was very tiny, she held herself with an air which made Barry quite forget her forlorn condition.

"How the mischief could I have ever taken her for a child?" he thought, with a faint flush of embarrassment, as he reached for the card. "I suppose it was because she seemed so little and helpless."

CHAPTER X.

SHIRLEY RIVES.

Having ordered two portions of a nourishing bouillon to be served at once, Lawrence picked out several dishes, then leaned back in his chair.

"I quite forgot to introduce myself," he said, with quick, boyish impulsiveness. "My name is Lawrence—Barry Lawrence."

A faint, shadowy smile curved the girl's lips. The warmth of the room was beginning to touch her cheeks with color, and make her even more lovely than before.

"It will be easier," she conceded gravely. "I am Shirley Rives."

"From Virginia?" Barry inquired quickly, then bit his lips. "I beg your pardon," he added contritely. "I forgot for a second that I meant to ask no questions."

"That one doesn't matter," she said quietly. "I am from Virginia. Since you've asked it, though, I'll venture one myself: Do you happen, by any chance, to be a Harvard man?"

Barry stared. "Why, yes!" he exclaimed. "How in the world did you guess?"

"You seem rather like other Cambridge men I've known," she answered slowly. "I had a cousin there, and his friends used to visit——"

She broke off abruptly, as if regretting that she had been so frank, and for a moment there was silence as she touched one of the forks nervously.

"I don't know that it makes much difference," she went on at length. "His name is Philip Calvert. Perhaps you knew him."

Barry laughed boyishly, and then bent forward with sparkling eyes. "Of course I did!" he exclaimed. "He was a junior the year I was graduated. To think of my meeting Phil Calvert's cousin in New York! I knew chance was going to bring me something pleasant when I started out this evening."

There was a moment's pause while the waiter placed the soup before them. Somehow, Barry had a feeling that the girl was more than hungry, and, though he did not see how he could take a mouthful after his luxurious dinner at the Waldorf, he did his best to seem ravenous himself, talking all the while, so that she might not see how little he was really eating.

The girl sipped the bouillon slowly and leisurely, listening to her companion's whimsical account of his progress down Fifth Avenue that night, and occasionally making a light comment of her own. One would never have guessed, to watch her, that she could have drained the cup at a single swallow.

Lawrence's surmise as to her desperate condition was more the result of intuition, helped on a little by details he observed from time to time, rather than anything he saw in her manner.

Little by little it was borne upon his consciousness that the extraordinary trimness which had puzzled him at first was nothing more than the painful neatness of extreme poverty, combined with innate good taste. The wide black hat was simply trimmed, and showed signs of wear. The perfectly fitting suit was of good material, but had been brushed and sponged until it was almost threadbare. The shirt waist of fine cambric looked as if it had been washed time and again with jealous care by the girl's own hands. On one sleeve a tear had been repaired with painful neatness.

All this Barry noticed as he talked on, wondering to himself how under the sun a cousin of his fastidious, seemingly wealthy, college mate could possibly have been reduced to such straits. But he asked no questions, nor did he in his manner betray the slightest touch of curiosity. He was only too thankful to see, under the influence of warmth and comfort and nourishing food, the color coming back into the girl's face, the sparkle to her eyes, and that tired droop of her mouth growing less and less noticeable.

As the meal progressed, however, his curiosity was gratified. It was inevitable that the discovery of a mutual friend should make some difference in the girl's attitude toward Lawrence. From discussing Calvert—who, it appeared, had been in Manila for over a year—the girl's story came out bit by bit.

More than likely Shirley Rives would never have thought of starting out to tell it to any one from beginning to end. But, while he did not express it by a single word, she seemed to feel Barry's sympathy, and be comforted by it. She had been bearing her troubles alone for so long that the temptation to talk a little about them to some one else was irresistible. And, last of all, she, too, seemed to feel that night something of Barry's attitude toward fate. She had come to the end of her rope, and was desperate. When one is in that pass conventions seem very petty, and life is stripped to the bones.

The story Lawrence gathered from a chance word here, a sentence there, was very old and hackneyed. It was really threadbare, yet the personality of the girl across the table lent it a vivid, enthralling interest.

Orphaned a year before, and left in straitened circumstances, Shirley Rives had taken the few hundred dollars remaining after the settlement of the encumbered estate, and come to New York to earn her living. Having no particular talent, and no influence, stenography seemed the only thing left her. She took a course in a correspondence school, and then obtained a position. Three months later the firm changed its organization, and she was cast adrift. She got another place, after eating into her diminishing capital, but the wholesale company was presently absorbed by a trust. Another period of enforced idleness ensued before she was taken on in a broker's office, only to be forced to leave by the unwelcome attentions of a junior partner.

That was three weeks ago. Since then she had failed to find anything. Her money became exhausted, and the board bill remained unpaid. The landlady gave her notice to pay or leave. The room had been rented late in the afternoon to another woman. Since then she had walked the streets, dazed, bewildered, not knowing what to do or where to go.

It was all told in snatches, but the thought of this girl, delicate and refined and well-bred, thrust out into the streets at such a time, without a penny, and with no place to go, made Barry's blood boil. Again came that intense desire to do something for her, accompanied by that same maddening sense of helplessness he had felt before.

"You were hurrying when I saw you first," he said at length.

She moved her shoulders a little. "It was partly to keep warm," she explained quietly, "and partly because I had just thought of a sort of forlorn hope."

"And that was——"

"A girl who used to work with me in the wholesale house; she was very nice, and we got to be good friends. She used to live on Forty-eighth Street, and I thought she would take me in to-night."

"How long is it since you've seen her?" Barry asked.

"Some months. I was tired, and it's a long way to Forty-eighth Street."

She tried to speak lightly, but Lawrence could see that old look of desperation, banished for a time, again lurking in her eyes.

"But what if she's moved?" he asked. "What if you shouldn't find her at the old address?"

She tried to smile, but her lips only quivered. And though she held her head high, like the thoroughbred she was, the expression in her eyes cut Barry to the quick.

"I—hadn't thought," she answered, in a low tone.

CHAPTER XI.

HIDE AND SEEK.

For a second Lawrence was silent, as a thought flashed through his brain as to the pathetic plight of the girl. The next instant he bent forward across the table, his clear gray eyes fixed upon hers, and holding her wavering gaze.

"I want to tell you a little story, Miss Rives," he said, in a hurried, almost jerky, tone, "and then I want you to do me a favor. Wait, please! Don't say you won't until you've heard me. This morning I left a miserable hall bedroom over on the West Side to walk the streets, because I could not face the woman I owed three weeks' rent."

She caught her breath quickly, and, as her eyes flashed to the wonderful emerald ring on his finger and back again to the pearls gleaming in his immaculate shirt, an expression of bewildered incredulity came into her face.

"I know," Barry went on hastily; "it seems impossible, but it's true. I'd had little to eat for days. My last nickel went for a cup of coffee. I had only a single penny left. I was cold and hungry and desperate. I had been out of a job for months, and there wasn't the slightest prospect of getting one. You see, there's scarcely a person in New York who could understand as I do what you have been through—and what may be before you now."

He paused an instant, but she made no comment. Her eyes were fixed intently on him as if his story held her entranced.

"For hours I walked the streets, then took refuge in a railway station to keep from freezing," Lawrence continued presently. "And there, when everything was blackest, when it seemed as if not a single hope remained, the wheel of fortune turned. From the lowest depths I was hoisted in a moment to a height I had come to believe impossible."

A faint, puzzled line had come into her low forehead. For a moment she waited, expecting him to continue. When he did not, she raised her eyebrows a trifle.

"But how——" she began.

"I can't tell you," he put in swiftly. "I've promised to keep silent. I can only say that I was given a very large sum of money to carry out certain conditions, and that those conditions carry with them no loss of self-respect. What I want you to do is to take a little—just a little—of this money to tide you over this period of hard luck."

A sudden color flamed into her face, and her lips parted. Before she could utter a word Barry went on pleadingly:

"Please don't say no, Miss Rives. The situation is desperate. If this girl friend of yours has moved, what will you do? Even if she is still there, I don't suppose you would keep on accepting hospitality from one who probably couldn't afford it. I can, you see, and if you'll only look upon me as Phil's friend, acting in his place, I'm sure you won't refuse."

For a long minute the girl sat staring into his frank, kindly face with eyes which seemed to plumb his very soul. Perhaps it was what she saw there that made her give in; perhaps it was the thoughts which flashed through her mind of the awful streets, wind-swept and dark and bitter cold, with even more poignant terrors lurking in the shadows. At all events, she sighed faintly, and reached for her gloves.

"Very well, Mr. Lawrence," she said quietly. "You may lend me—ten dollars."

"But that isn't——"

"It is quite enough," she put in decidedly, "to make me grateful to you as long as I live. Would you mind—if we go now? It's getting late."

Without further protest, Barry paid the bill at once, and helped her on with her coat. As they reached the street he handed her a ten-dollar bill, which she slipped into her worn glove with another brief word of thanks.

The ride uptown was a rather silent one. Barry did most of the talking, for he felt that the girl would rather say little.

At Forty-eighth Street they got out, and, turning westward, walked briskly through the chilly street. As they approached a certain shabby-looking house midway in a block, Miss Rives, glancing upward, gave an exclamation of satisfaction at the sight of a light in the front room on the top floor.

"I'm sure Sally's still there," she said, turning to Lawrence. "She used to sit up reading till all hours." She hesitated an instant, and then went on more slowly: "I think I'd better go to the door alone. The woman who keeps the house is very kind, and, even if Sally's gone, she'll take me in. Good-by, Mr. Lawrence, and—thank you—a thousand times, for what you have done. Will you—give me your address so that I can send back the money—when I have it?"

Barry's fingers closed firmly over the hand she held out.

"I'm at the St. Albans just now," he returned. "But I probably won't stay there long. Wouldn't it be better if I looked you up to see how you're getting on?"

For a bare second Shirley Rives hesitated. Then she turned away, and began mounting the steps.

"I should be very glad to see you again, Mr. Lawrence," she answered. "Good night!"

From a little distance Barry watched her ring the bell, saw the door open with almost no delay at all, and heard a brief murmur of conversation. When the girl finally stepped into the house and the door closed, he turned away with a sigh of satisfaction, and started back toward Broadway.

He had not gone more than a few steps when he saw approaching the lights of a rapidly moving carriage, and a moment later a well-appointed private brougham passed him, the iron-shod hoofs of the spirited horses striking sparks from the icy street. A vague, languid curiosity stirred him as to what a conveyance of that sort was doing there at that hour, but it swiftly vanished in the interest of another discovery.

Reaching the corner of Eighth Avenue, he happened to glance swiftly to his right, and noticed a man standing silently in the corner of a darkened doorway. There was nothing very extraordinary in this, save for the fact that it was a night which offered no temptations for loitering in the street; but there was something about the powerful, square-shouldered figure, accentuated by the heavy ulster which enveloped it, that struck Lawrence as oddly familiar. The coat collar was turned up and buttoned close; the brim of the soft felt hat was pulled well down, so as to conceal the face, but in spite of that a bit of grizzled beard was visible, which stimulated Barry's memory.

In that momentary hesitation on the curb he remembered that just such a man had been standing in another doorway near the restaurant as they left it less than an hour before, and he wondered at the curious coincidence which should bring about this second meeting.

Before he reached Broadway Lawrence began to have doubts as to whether it really was a coincidence or not. Another man would have thought nothing of the matter; but Barry had lately been through an experience of shadowing which taught him many things about the methods of private detectives and others of their ilk, which had produced in him a habit of being constantly on guard.

At least it would do no harm to be sure, he thought, and, rounding the corner of Broadway, he hastened forward a few steps to the entrance of a moving-picture theater. Once within its shelter, he swiftly found a spot where the plate-glass windows of the ticket booth acted as an admirable reflector. Then, back squarely to the street, and eyes riveted on the improvised mirror, he leisurely undid his fur coat, as leisurely produced a cigarette from his case, and hunted for his match box.

It was just as he struck a light that his patience was rewarded. In the glass he saw the stranger steal silently into view around the corner, hesitate for the fraction of a second, then, catching sight of Barry's back, as softly withdrew out of sight.

"So that's your little game, is it?" Lawrence reflected, with a grim smile, as he lighted the cigarette with care, and flicked the match into the street. "Looks as if there might be a bit of fun in this."

Buttoning his coat, he started briskly down Longacre Square, swinging his stick with the air of a man who was just beginning a constitutional. In front of the Astor he paused a second, as if half minded to enter the brilliant hostelry. Then, without warning, he turned abruptly, stepped into the street, and headed for the Times Building. As he did so he caught a glimpse, out of the corner of his eye, of his pursuer, half a block in the rear.

With a chuckle of amusement, Barry passed the outdoor subway entrance, and walked swiftly into the lower floor of the building. The instant he was inside, he hastened his steps, hurried past the stairs leading down into the underground road, pushed his way through the throng which crowded the big drug store that occupied the ground floor, and emerged on Forty-second Street.

A crosstown car was just getting up speed as he dashed across the street; and with some difficulty he raced forward and swung himself aboard. A backward glance showed that his bearded friend was nowhere in sight, and Lawrence smiled again.

Nevertheless, he did not relax his vigilance. Making his way through to the front of the car, he sat down on one of the little seats just behind the motorman, and made no attempt to alight until Madison Avenue had been reached. Here he slipped off, dodged around the front of the car, slid across the slippery pavement, and was engulfed in the comparative shadow of the Manhattan in an instant.

The three blocks to Forty-fifth were passed in as many minutes. Around the corner of the cross street, however, he sought a secluded doorway, and waited patiently for as much as five minutes, with the pleasant, ever-growing conviction that his man had been eluded.

"Not quite clever enough, my friend," he murmured, as he crossed the dark and rather silent street, heading for the bright entrance of the St. Albans near Fifth Avenue.

Part way down the block stood a pair of old-fashioned brownstone houses, and, as he passed the shadowy bulk of the first high stoop, Barry chuckled again.

"Not quite clever enough," he repeated amusedly. "You'll have to get up a trifle early to——"

Crash! From behind, something struck his head with a crushing force that sent him to his knees, stick flying one way, top hat the other.

With a hoarse cry of anger, he strove dazedly to turn and grapple with the unknown assailant. Before he could do so the heavy weapon descended for the second time. There was a shower of stars, a sickening sense of faintness, and, with a groan, Lawrence toppled forward on his face, to lie still and silent on the icy pavement.

CHAPTER XII.

PUZZLED.

How long Barry Lawrence lay there unconscious he did not know. Afterward he realized that it could have been no more than a minute or two, but at the moment he was too occupied with what was occurring near him to waste time on that score.

Even before he opened his eyes he was vaguely aware that a struggle was going on close at hand. The thud of feet, the heavy breathing, mingled with occasional oaths, subdued, but fervent, told him that, and acted as a spur on his dazed senses.

A moment later, as he pulled himself to a crouching position on the pavement, he discerned through the darkness two figures swaying in close embrace a dozen feet away.

What did it mean? Who were they? He could not understand why they were fighting there, instead of carrying out the object of their attack on him. Then, as his sight cleared, he suddenly discovered that one of them was the bulky man in the soft hat whom he had lately been pluming himself on having given the slip so completely. The other was taller and wore no overcoat; beyond that Lawrence could make out no distinguishing features.

Suddenly, out of the bewildering chaos of Barry's mind, came the swift realization that one of these men was apparently on his side. There could be no question that one was fighting in his behalf to prevent the other from carrying out the object of the cowardly attack, whatever that might be.

Of reason or motive for that attack, Barry knew none, but he was strongly moved for a moment to join in the mix-up, and get in a blow or two he was aching to deliver. He even secured his hat and stick, and was on the point of struggling to his feet, when he remembered that he had no idea which was the friend and which the enemy. He was not even sure that either of them was a friend.

What could he do?

The answer came on the very heels of the unspoken question. The gate in the low, old-fashioned iron fence close beside him was partly open. Beyond loomed the friendly shadow of the high stoop.

Instinctively, with his brain still a little muddled from the blow he had received, Barry crept silently through the gate, casting a swift, sidelong glance at the struggling pair. He saw that the taller man was evidently getting the worst of if, and apparently trying his best to break away. In another moment the fellow with the beard would be free—free to return and complete his work; for by this time Lawrence had come to the conclusion that he was the one responsible for the assault.

Without a second's delay the Harvard man slipped through the gate and closed it softly behind him. Rising to his feet, but stooping low, he felt his way forward, went down a couple of steps, and pushed against the iron grille which gave access to a space under the stoop, and thence to the basement door.

To his surprise it yielded to his touch, and a moment later he was ensconced in the little square, dark space, the grille closed and latched, peering through the openings in the ornate wrought ironwork.

He was no more than safe before he heard the beat of running feet on the pavement, and saw a tall, thin figure dart past his hiding place, and disappear toward Madison Avenue. An instant later another, bulkier shadow appeared more slowly, and paused by the low fence.

It was the mysterious person with the beard, and Barry shrank swiftly back, wondering what he meant to do.

There was a moment's pause; then the low gate was pushed open, and the stranger stepped toward the grille. Reaching it, he shook it briskly, but the latch held. From where he had retreated in the shadow, with one arm thrown up to prevent his face from being seen, Barry heard the unknown give a guttural growl of mingled surprise and impatience. A brief pause followed, during which his irregular breathing sounded clear and distinct. Then he turned and walked back to the sidewalk, the gate clicking behind him.

For a minute or two Barry did not move, but at length, unable to restrain his curiosity, he stole to the grille and peered through. The stranger was still standing near the fence, gazing intently up and down the street. Presently he disappeared toward Madison Avenue, and Barry, after waiting a few moments, undid the grille and stole out.