Mary strikes the shuttle-cock a hard blow with the battle-door. Up it goes into the air, and down it falls into the grass. There it is; but the next thing to be done is to find it. Who will pick it up?

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Nursery, May 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Nursery, May 1881, Vol. XXIX

A Monthly Magazine for Youngest Readers

Author: Various

Release Date: September 14, 2012 [EBook #40756]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, MAY 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

| PAGE | |

| The Bold Soldier-Boys | 129 |

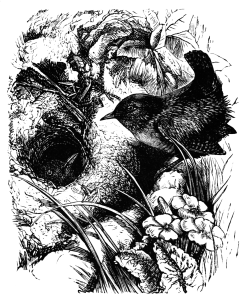

| Papa Robin | 132 |

| Carlo and the Ducks | 135 |

| Picking Oranges | 139 |

| Mary and Jenny | 144 |

| Drawing-Lesson | 145 |

| Piggy's Spoon | 146 |

| Bouncer | 148 |

| Harry and John | 154 |

| "Inches" | 155 |

| PAGE | |

| The Army of Geese that Came over the Lea | 131 |

| The Naughty Cat | 136 |

| The May-Queen | 141 |

| Sing, Pretty Birds | 143 |

| The Traveller | 147 |

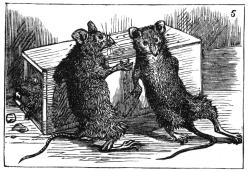

| The Mouse-Trap | 151 |

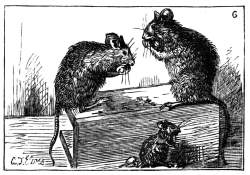

| One Cat and Two Pigs | 152 |

| Small Beginning | 157 |

| Jenny Wren | 159 |

| Daddy Frog (with music) | 160 |

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 5.

VOL. XXIX.—NO. 5.

There stood the enemy in stern defiance,—four chairs,[130] one table, and a sofa,—there they stood, with a plastered wall in their rear, and calmly awaited the attack.

The fiery steed of Colonel Bob reared and plunged, as if eager to dash upon the foe. The roll of the drum made a fearful sound. The standard-bearer waved his flag. The army came rushing on. Snap the dog barked furiously. But above all the din was heard the shout of Colonel Bob, "Forward, my brave boys!"

Not a picture started from its frame. Not a chair moved. But all of a sudden the door opened, and a face looked in. It was Colonel Bob's papa.

"What's all this noise about, Robert?" said he. "This is not the place for such games. Go out of doors if you want to play soldier. I can't have such a drumming and shouting in the house."

This was rather a damper on Colonel Bob's military zeal; but what came next was still worse.

"Do any of you boys know where to-day's 'Advertiser' is?" asked papa.

Colonel Bob came down from his high horse, threw aside his plume, took off his chapeau, and handed it to his papa.

There was the "Advertiser" of that very day, folded up as a soldier-cap.

"Well, that's pretty business," said his papa, laughing. "Please give me a chance to read the papers before you use them in this way." And he went out and shut the door.

Colonel Bob stood leaning on his horse as if in deep thought. At last he said, "Boys, this movement has failed. We must change our base. Follow me." And he led the army out into the back garden.

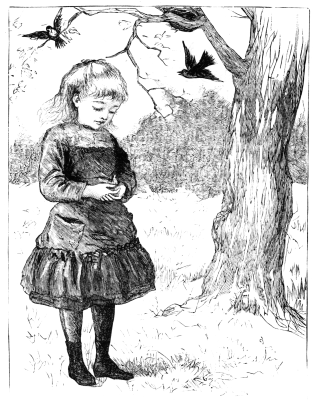

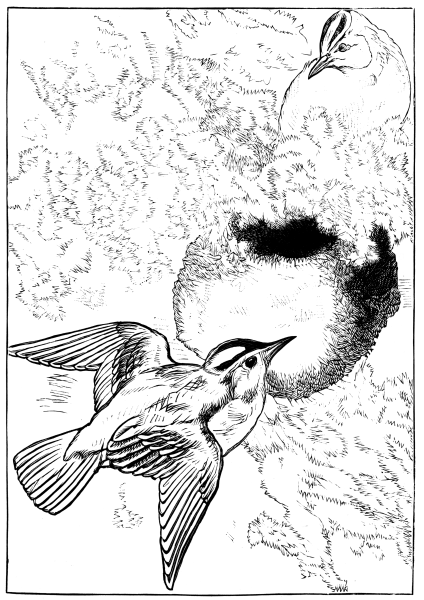

By and by she heard a shrill chirping. "Poor little bird," she thought, "where can it be? Is it hurt?" She went out into the yard, and looked about her.

There, under a tree, was a baby-bird that had fallen out of its nest. Elizabeth took it up gently. As it lay in her hand, it looked like a soft ball. It chirped as loud as it could, and fluttered.

"Poor birdie," said Elizabeth, "I will try and take you home." And she looked up into the tree. She could see the nest the fledgling had tumbled out of; but she was not[133] tall enough to reach it: so she stood on a knot in the trunk of the tree, and put the nestling in its home.

She saw the father and the mother-bird in the tree, and said to herself that they would take care of the little one. Then she went back to her reading.

Pretty soon she heard the chirping again. This time she knew where to look, and there was the baby-bird on the ground, crying and fluttering as before.

"Papa and mamma Robin ought to take care of you, birdling," she said. But she stepped on the knotted tree-trunk, and put back the bird a second time.

Then she sat down on the doorstep, and watched to see[134] what the parent-birds would do. They flew here and there about the nest, and sang a few notes that Elizabeth knew must be bird-talk. She wondered if they were trying to find a better place for their baby.

But as she was thinking how much care they were taking of it, out tumbled the little one a third time. "You stupid old robin!" she cried. "Do you expect some one to be putting back your birdie for you all day? Why don't you keep it in the nest?"

She picked up the birdie, and was about to put it back a third time, when, as she held it, a strange thing happened; for down flew the robin, and gave her a sharp peck on the forehead.

Elizabeth stood still. She didn't know what to make of this. But soon she began to laugh; and then she put the baby-bird gently on the ground, and went away. She at last understood what papa Robin meant to say to her by his peck. This is it: "Don't interfere when I'm teaching my child to fly. You are very big, and perhaps you know a great deal; but you don't seem to know that it's not right to keep birds in the nest all summer. They would never find out what their wings are for."

But Carlo was in chase of two ducklings, and did not mind Jane's call. Of course the ducklings took to the water. Carlo ran after them to the water's edge, but there he stopped.

What stopped him? Jane was tugging pretty hard at the string. That was one thing that held him back; but that[136] was not all. Carlo was not fond of the water; but he would not have stopped for that.

I will tell you what stopped him. While the ducklings were swimming away for dear life, the old mother-duck came sailing boldly up, with her great yellow beak, and faced Master Carlo.

She looked like a sloop-of-war all ready for action. Carlo was a brave dog; but he was afraid of her, for all that. So he stood still and barked.

Madam Duck did not mind his noise in the least. She quacked at him fiercely. This is what she meant to say: "Look here, my young friend, you are a dog, and I am a duck. You are at home on the land, but I am at home on the water. Bark as much as you please, but, if you know what is good for your health, keep out of this pond, and let my ducklings alone."

"Do you hear that, Carlo?" said Jane. "Now don't stop to answer, but come with me like a good dog, and we will have a run in the woods."

And then Carlo gave up his chase of the ducks, and went quietly where Jane led him.

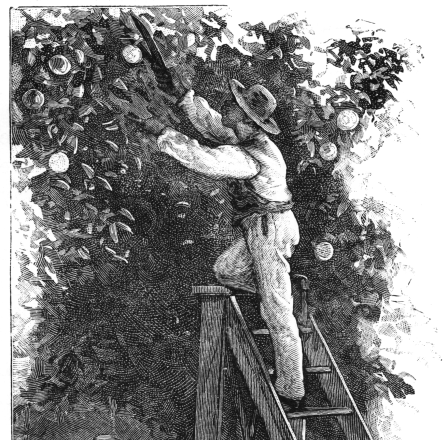

But, while the boys and girls in the North are wearing mittens and tippets and thick coats when they go out to play, Willy and Ben are running about bare-headed in the orange-groves, or plucking roses from the garden.

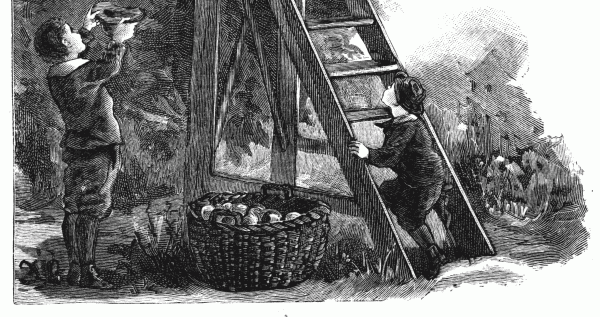

All around the house are orange-trees, and in among the glossy green leaves hang the great yellow juicy oranges. The fruit is ripe early in December, and ready to be picked.

Miles, the colored man, takes his big clippers and goes up the high step-ladder which he has placed near the tree. He cuts each orange from the branch, taking care not to get hurt by the long, sharp thorns.

Willy stands at the foot of the ladder, ready to catch the oranges as Miles tosses them down. Sometimes they pick five or six baskets in an afternoon. Miles says Willy is a "bery good catch." He sometimes tires of catching them; but he never tires of eating them.

I looked into the packing-room this morning, and there[140] lay seventeen hundred yellow balls. Papa lets both his little boys help wrap the oranges. Each orange is wrapped in a piece of tissue-paper that is cut just the right size. Willy always says as he begins, "Now let's see who'll beat!" Do you know what he means?

Ben cannot wrap oranges as fast as Willy; but, as they are wrapped, he hands them to papa to pack in boxes. He can read the word "Boston" that papa writes in black letters on the outside of the boxes.

Of course papa pays his workers, and they take their money all to mamma to keep for them. They have so much whispering to do about it, that I think they are saving it to buy holiday gifts.

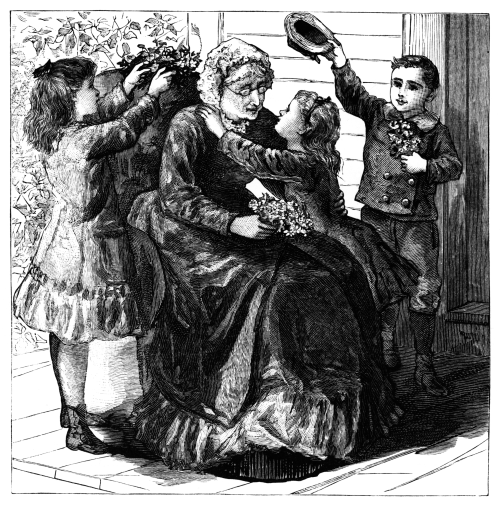

THE MAY-QUEEN.

"When I was little," said grandma Gray, "We used to welcome the month of May With a song and a dance on the village green, Choosing and crowning our May-day queen. We used to choose of the prettiest girls, The one who had the sunniest curls, The one who had the merriest eyes, As clear and bright as the May-day skies. "We made her throne of the daisies white, And of yellow buttercups, golden bright, And we twined gay blossoms about the hair Of our dear little queen so sweet and fair." So grandma said, and the children heard, And a loving thought in each heart was stirred; And they whispered together, and laughed in glee, "Dear grandmamma shall our May-queen be!" |

| Sing, pretty birds, and build your nests, The fields are green, the skies are clear; Sing, pretty birds, and build your nests, The world is glad to have you here. Among the orchards and the groves, While summer days are fair and long, You brighten every tree and bush, You fill the air with loving song. At early dawn your notes are heard In happy greeting to the day, Your twilight voices softly tell When sunshine hours have passed away. Sing, pretty birds, and build your nests, The fields are green, the skies are clear; Sing, pretty birds, and build your nests, The world is glad to have you here.

M. E. N. HATHAWAY. |

|

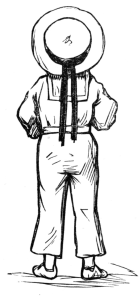

| Mary strikes the shuttle-cock a hard blow with the battle-door. Up it goes into the air, and down it falls into the grass. There it is; but the next thing to be done is to find it. Who will pick it up? |

Jenny stands with her hands behind her. She has a roguish look. What has she in her hands? Is it an apple? No. Is it an orange? No. Is it a ball? No. Guess again. Ah! I know what it is. It is the shuttle-cock.

G. H. I. |

|

DRAWING-LESSON.

DRAWING-LESSON.

On one side of his house there was a door that opened into a pen. The pen was in the orchard where the sweet apples grew. Sometimes in summer the apples would fall down from the trees into the pen; then piggy would pick them up and eat them. Sometimes they would strike him on his back when they fell; but he did not mind that; he was always glad to get them.

He had his bed of warm straw to sleep in at night, and every day he had as much as he wanted to eat. He had all a pig could wish for: so he was contented. One morning farmer Jackson brought a pailful of milk for piggy's breakfast. He poured the milk into the trough, and piggy made haste to come and eat it.

While he was eating, something hard and cold came into his mouth. He bit it, but found that it was not good: so he left it. He ate up all the milk. When it was gone, he saw a bright silver spoon in the bottom of the trough.

"Oh!" said piggy, "I see how it is. They would like to have me eat with a spoon; but they would never make me fat in that way. I should be hungry all the time. Now I can eat fast and grow fast, and I like my own way best."

So piggy turned up his nose at the spoon. Then he went out into the pen, and began to root in the dirt to find bits of apple. "Fine work I should make using a spoon," said piggy, and he laughed whenever he thought of it.

At night farmer Jackson came to bring his supper. He saw the spoon in the trough, took it out and carried it into the house. When his wife saw it, she said somebody had been very careless, and dropped the spoon into piggy's pail.[147] She could not find out who had done it, though she asked everybody. Then she thought that perhaps she had done it herself. She was glad to get her spoon back again, and piggy was glad to have it taken from the trough.

He had left the print of his teeth on it: so it was afterwards called "Piggy's spoon."

"Have what?" said grandma smiling, as she looked up from her book. "The measles?"

"Why, grandma, of course it isn't the measles," said Ned, the eldest. "It is a dog,—a real puppy. Mrs. James told Arthur she would give it to him, if you were willing."

Grandma thought of her nice flower-beds and her well-kept driveway. She did not want to have a dog running about in them. But then she saw the three wistful faces waiting for her answer, and so she said "Yes."

Mrs. James had promised that she would bring it to Arthur by Saturday. All the boys were in haste for the[150] day to come, and Arthur said, "Now, mamma, there will be three days more and then 'dog-day.'"

Saturday came at last. Arthur sat by the front-door watching. About four o'clock in the afternoon, he came to me and said, very sadly, "Do you really think she will come to-day, mamma?"—"Yes," said I.

He took his seat on the steps, and in a few minutes I heard a joyful cry: "Here's my dog! here's my dog!" The other boys joined in the shout. Was there ever such joy!

Bouncer,—for that was the puppy's name,—was a fine water-spaniel. He grew very fast, and proved very kind and playful. The three boys became very fond of him. The first thing in the morning, and the last thing at night, they would all rush out of doors for a romp with Bouncer.

He was always ready for a frolic. Nothing pleased him so much as a dash into the lake. Then he was in his glory. He would spring into the water after any thing that the boys would throw.

Once he saved a man's hat that had blown overboard; and if the man had gone over with his hat, I have no doubt that Bouncer would have saved him too. But, as the man was safe on shore all the time, Bouncer had no chance to prove himself a hero. That wasn't Bouncer's fault, you know.

|

|

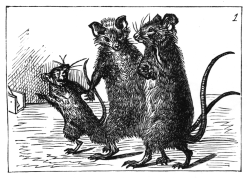

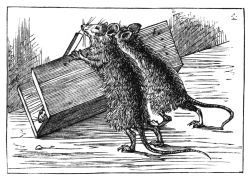

THE cheese smelt tempting in its little house: "I'll get it, never fear!" cried Master Mouse. | Caught in the trap, with all their might and main, His parents try to get him out again. |

|

|

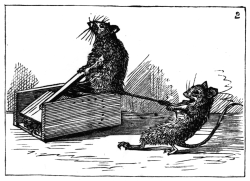

| Alas! alas! exertions well applied Bring but a swift collapse undignified. | A happy thought: "We'll roll the box about, And thus, perchance, get valiant Brownie out!" |

|

|

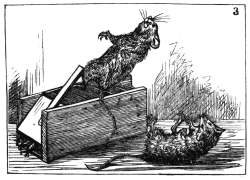

| Still happier thought: a wall its aid extends; And Brownie, thankful for such clever friends, | Darts out in triumph, bearing high the cheese, Then shares the well-won spoil, and feasts at ease. |

| Harry waves his flag to stop a train of cars. He has seen a man do it at the railroad station. But the train rushes by, and does not mind him in the least. This makes him look sad. John stands and looks on. He is dressed in a new sailor-suit. He feels so grand that he does not care whether the train stops or not. There is a very broad grin on his face. We should see it if we could make him turn round and look at us.

J. K. L. |

|

His papa and mamma were Americans; but their little boy was born in Assam, and until he was four years old he had never seen any other country.

Now, you will want to know where Assam is. I will tell you. It is a kingdom in India, lying west of China, and south of the great Himalaya Mountains. Some peaks of these mountains can be seen on a clear day from the house where Inches lived.

One morning early, our little friend woke, and called out in the Assamese language (for he could not speak English), "Tezzan, take me."

Tezzan his "bearer"—so a man-nurse is called in Assam—came quickly, and dressed his little charge. Then, after giving him a slice of dry toast and a nice plantain for his breakfast, he took the little boy by the hand, and started out with him for their regular morning-walk.

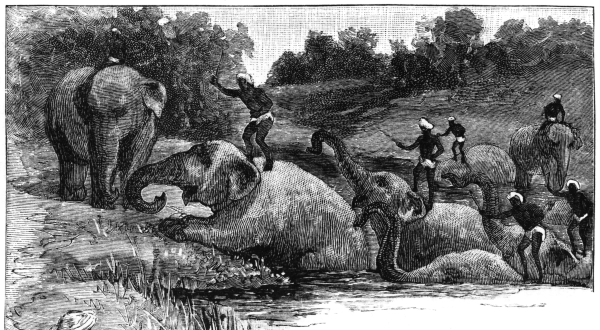

They went down along the bank of the Brahmaputra River, and saw many sights that would look very strange to Americans. A little below the house, Inches called on Tezzan to stop, and let him watch some elephants that were swimming across the river. He called the elephant a hatee, giving the "a" in the word the same sound we give it when we say father.

All they could see of the elephants was the tops of their heads, and occasionally their trunks when they threw them out of the water for a fresh breath of air. The drivers stood on the necks of the elephants, with only a rope, tied round the great creatures' necks, to hold on by.

By and by they came struggling up the bank, one after another,—eight of them,—and stood panting and dripping to rest a little. Scarcely had they set their feet on dry land when a little ferry-boat came steaming along, and just as she got close to the bank she blew a long, loud whistle.

The elephants were frightened, and ran snorting and trumpeting right up the road where Inches and his bearer were standing. Inches was very much frightened, and ran too. But no harm was done, and after a little while Inches had a good laugh, when he thought how the elephants ran away from the little bustling steamer.

After this was all over and the elephants were slowly jogging along, Inches and his bearer started on again. They met many people; but very few of them were white. There were only fifteen white children to be found for many miles: so they, of course, knew each other well.[157]

Down the road, further on, they came to a sweetmeat-vender's shop. His candies and sweets were put on flat bamboo or cane plates, and all arranged outside the shop itself, on a platform made of bamboo.

Inches wished Tezzan to buy some sweets for him; but they had brought no pice, so could not. (Pice are small copper coins used in India, worth about three-fourths of one cent each.)

The little boy was on the point of crying, when he heard his mamma calling; and, sure enough, there she was, and papa, too, waiting for him in the pony-carriage. He ran quickly, and climbed into his mamma's lap, and was soon home again.

|

Jenny Wren's a lady, Very quiet she: That's her pretty mansion In the hollow tree. Peep into her parlor, Carpeted with down; There you'll see her sitting In her modest gown. Jenny Wren is busy, Summer days are near, And she has a houseful: Listen, and you'll hear. Little mouths are open From the hour she wakes, And to feed her darlings All her time it takes. Jenny Wren is moving: Breezes hurry by; Purple leaves are falling; Chilly grows the sky. Long before the snowflakes Through the orchard roam, Should you call on Jenny, Nobody's at home.

GEORGE COOPER. |

|

Transcriber's Notes: Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

The original text for the January issue had a table of contents that spanned six issues. This was divided amongst those issues.

Additionally, only the January issue had a title page. This page was copied for the remaining five issues. Each issue had the number added on the title page after the Volume number.

End of Project Gutenberg's The Nursery, May 1881, Vol. XXIX, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NURSERY, MAY 1881, VOL. XXIX ***

***** This file should be named 40756-h.htm or 40756-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/0/7/5/40756/

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Music

transcribed by June Troyer.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For forty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.