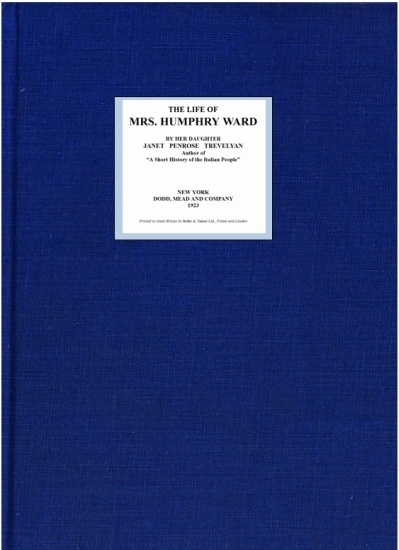

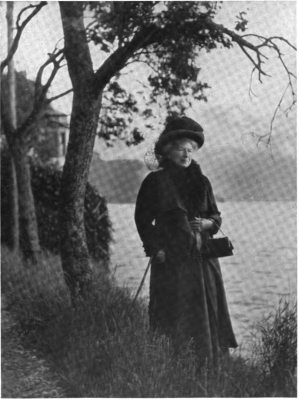

MARY WARD AT THE AGE OF TWENTY-FIVE

FROM A WATER-COLOUR PAINTING BY MRS A. H. JOHNSON

BY HER DAUGHTER

JANET PENROSE TREVELYAN

Author of

“A Short History of the Italian People”

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1923

Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd., Frome and London

TO

DOROTHY MARY WARD

MY warmest thanks are due to the many friends who have helped me, directly or indirectly, in the writing of this book, but especially to all those who have sent me the letters they possessed from Mrs. Ward, or who have given me leave to publish their own. Mr. Henry Gladstone kindly looked out for me the letters written by Mrs. Ward to Mr. Gladstone during the Robert Elsmere period; Mrs. Creighton did the same for the long period covered by Mrs. Ward’s correspondence with the Bishop and with herself; Miss Arnold of Fox How sent me many valuable letters belonging to the later years. So with Mrs. A. H. Johnson, Mrs. Conybeare, Mrs. R. Vere O’Brien, Sir Robert Blair, Mr. Leonard Huxley, Mrs. Reginald Smith, Lord Buxton, M. Chevrillon, Miss McKee, Mrs. Turner, Miss Gertrude Wood, and many others, and although the letters may not in all cases have been suitable for publication, they have given me many valuable side-lights on Mrs. Ward’s life and work.

To Mrs. A. H. Johnson my special thanks are due for permission to reproduce her water-colour portrait of Mrs. Ward, and to Mrs. T. H. Green for much help in connexion with the Oxford portion of the book.

No book at all, however, could have been produced, even from the material so generously placed at my disposal, had it not been for the constant collaboration of my father and sister, whose help in sifting great masses of papers and in advising me in all difficulties has been my greatest support throughout this task.

J. P. T.

BERKHAMSTEAD,

July, 1923.

| PAGES | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| CHILDHOOD | |

| Mary Arnold’s Parentage—The Sorells—Thomas Arnold the Younger—Marriage in Tasmania with Julia Sorell—Conversion to Roman Catholicism—Return to England—The Arnold Family—Mary Arnold’s Childhood—Schools—Her Father’s Re-conversion—Removal to Oxford | 1-16 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| LIFE AT OXFORD, 1867-1881 | |

| Oxford in the ‘Sixties—Mark Pattison and Canon Liddon—Mary Arnold and the Bodleian—First Attempts at Writing—Marriage with Mr. T. Humphry Ward—Thomas Arnold’s Second Conversion—Oxford Friends—The Education of Women—Foundation of Somerville Hall—The Dictionary of Christian Biography—Pamphlet on “Unbelief and Sin” | 17-34 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| EARLY YEARS IN LONDON—THE WRITING OF ROBERT ELSMERE, 1881-1888 | |

| Mr. Ward takes work on The Times—Removal to London—The House in Russell Square—London Life and Friends—Work for John Morley—Letters—Writer’s Cramp—Miss Bretherton—Borough Farm—Amiel’s Journal Intime—Beginnings of Robert Elsmere—Long Struggle with the Writing—Its Appearance, February 24, 1888—Death of Mrs. Arnold | 35-54 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| ROBERT ELSMERE AND AFTER, 1888-1889 | |

| Reviews—Mr. Gladstone’s Interest—His Interview with Mrs. Ward at Oxford—Their Correspondence—Article in the Nineteenth Century—Circulation of Robert Elsmere—Letters—Visit to Hawarden—Quarterly Article—The Book in America—“Pirate” Publishers—Letters—Mrs. Ward at Hampden House—Schemes for a New Brotherhood | 55-80 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| UNIVERSITY HALL, DAVID GRIEVE AND “STOCKS,” 1889-1892 | |

| Foundation of University Hall—Mr. Wicksteed as Warden—The Opening—Lectures—Social Work at Marchmont Hall—Growing Importance of the Latter—Mr. Passmore Edwards Promises Help—Our House on Grayswood Hill—Sunday Readings—The Writing of David Grieve—Visit to Italy—Reception of the Book—Letters—Removal to “Stocks” | 81-103 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE STRUGGLE WITH ILL-HEALTH—MARCELLA AND SIR GEORGE TRESSADY—THE BUILDING OF THE PASSMORE EDWARDS SETTLEMENT, 1892-1897 | |

| Mrs. Ward much Crippled by Illness—The Writing of Marcella—Stocks Cottage—Reception of the Book—Quarrel with the Libraries—The Story of Bessie Costrell—Friends at Stocks—Letter from John Morley—Sir George Tressady—Letters from Mrs. Sidney Webb and Mr. Rudyard Kipling—Renewed attacks of Illness—The Building and Opening of the Passmore Edwards Settlement | 104-122 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| CHILDREN AND ADULTS AT THE PASSMORE EDWARDS SETTLEMENT—THE FOUNDATION OF THE INVALID CHILDREN’S SCHOOL, 1897-1899 | |

| Beginnings of the Work for Children—The Recreation School—The Work for Adults—Finance—Mrs. Ward’s interest in Crippled Children—Plans for Organizing a School—She obtains the help of the London School Board—Opening of the Settlement School—The Children’s Dinners—Extension of the Work—Mrs. Ward’s Inquiry and Report—Further Schools opened by the School Board—After-care—Mrs. Ward and the Children | 123-142 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| HELBECK OF BANNISDALE—CATHOLICS AND UNITARIANS—ELEANOR AND THE VILLA BARBERINI, 1896-1900 | |

| Origins of Helbeck—Mrs. Ward at Levens Hall—Her Views on Roman Catholicism—Creighton and Henry James—Reception of Helbeck—Letter to Creighton—Mrs. Ward and the Unitarians—Origins of Eleanor—Mrs. Ward takes the Villa Barberini—Life at the Villa—Nemi—Her Feeling for Italy | 143-164 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| MRS. WARD AS CRITIC AND PLAYWRIGHT—FRENCH AND ITALIAN FRIENDS—THE SETTLEMENT VACATION SCHOOL, 1899-1904 | |

| Mrs. Ward and the Brontës—George Smith and Charlotte—The Prefaces to the Brontë Novels—André Chevrillon—M. Jusserand—Mrs. Ward in Italy and Paris—The Translation of Jülicher—Death of Thomas Arnold—The South African War—Death of Bishop Creighton and George Smith—Dramatization of Eleanor—William Arnold—Mrs. Ward and George Meredith—The Marriage of her Daughter—The Vacation School at the Passmore Edwards Settlement | 165-186 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| LONDON LIFE—THE BEGINNINGS AND GROWTH OF THE CHILDREN’S PLAY CENTRES, 1904-1917 | |

| Mrs. Ward’s Social Life—Her Physical Delicacy—Power of Work—American Friends—F. W. Whitridge—Plans for Extending Recreation Schools for Children to other Districts—Opening of the first “Evening Play Centres”—The “Mary Ward Clause”—Negotiations with the London County Council—Efforts to raise Funds—No help from the Government till 1917—Two more Vacation Schools—Organized Playgrounds—Fenwick’s Career—“Robin Ghyll” | 187-206 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| THE VISIT TO THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA, 1908 | |

| Invitations to visit America—Mr. and Mrs. Ward and Dorothy sail in March, 1908—New York—Philadelphia—Washington—Mr. Roosevelt—Boston—Canada—Lord Grey and Sir William van Horne—Mrs. Ward at Ottawa—Toronto—Her Journey West—Vancouver—The Rockies—Lord Grey and Wolfe—Canadian Born and Daphne | 207-223 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| MRS. WARD AND THE SUFFRAGE QUESTION | |

| Early Feeling against Women’s Suffrage—The “Protest” in the Nineteenth Century—Advent of the Suffragettes—Foundation of the Anti-Suffrage League—Women in Local Government—Speeches against the Suffrage—Debate with Mrs. Fawcett—Deputations to Mr. Asquith—The “Conciliation Bill”—The Government Franchise Bill—Withdrawal of the Latter—Delia Blanchflower—The “Joint Advisory Committee”—Women’s Suffrage passed by the House of Commons, 1917—Struggle in the House of Lords—Lord Curzon’s Speech | 224-245 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| LIFE AT STOCKS, 1908-1914—THE CASE OF RICHARD MEYNELL—THE OUTBREAK OF WAR | |

| Rebuilding of Stocks—Mrs. Ward’s Love for the Place—Her Way of Life and Work—Greek Literature—Politics—The General Elections of 1910—Visitors—Nephews and Nieces—Grandchildren—Death of Theodore Trevelyan—The “Westmorland Edition”—Sense of Humour—The Case of Richard Meynell—Letters—Last Visit to Italy—The Coryston Family—The Outbreak of War | 246-263 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| THE WAR, 1914-1917—MRS. WARD’S FIRST TWO JOURNEYS TO FRANCE | |

| Mrs. Ward’s feeling about Germany—Letter to André Chevrillon—Re-organization of the Passmore Edwards Settlement—President Roosevelt’s Letter—Talk with Sir Edward Grey—Visits to Munition Centres—To the Fleet—To France—Mrs. Ward near Neuve Chapelle and on the Scherpenberg Hill—Return Home—England’s Effort—Death of F. W. Whitridge and of Reginald Smith—Second Journey to France, 1917—The Bois de Bouvigny—The Battle-field of the Ourcq—Lorraine—Towards the Goal | 264-287 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| LAST YEARS: 1917-1920 | |

| Mrs. Ward at Stocks—Her Recollections—The Government Grant for Play Centres—The Cripples Clause in Mr. Fisher’s Education Act—The War in 1918—Italy—The Armistice—Mrs. Ward’s third journey to France—Visit to British Headquarters—Strasburg, Verdun and Rheims—Paris—Ill-health—The Writing of Fields of Victory—The last Summer at Stocks—Mrs. Ward and the “Enabling Bill”—Breakdown in Health—Removal to London—Mr. Ward’s Operation—Her Death | 288-309 |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| Mary Ward at Twenty-five. From a water-colour painting by Mrs. A. H. Johnson | Frontispiece |

| Borough Farm. From a water-colour painting by Mrs. Humphry Ward | 45 |

| Mrs. Ward in 1889. From a photograph by Bassano | 82 |

| Mrs. Ward in 1898. From a photograph by Miss Ethel M. Arnold | 149 |

| Mrs. Ward and Henry James at Stocks. From a photograph by Miss Dorothy Ward | 252 |

| Mrs. Ward beside the Lake of Lucerne. From a photograph by Miss Dorothy Ward | 262 |

IS the study of heredity a science or a pure romance? For the unlearned at least I like to think it is the latter, since no law that the Professors ever formulated can explain the caprices of each little human soul, bobbing up like a coracle over life’s horizon and bringing with it things gathered at random from an infinitely remote and varying ancestry. It is, I believe, generally known that the subject of this biography was a granddaughter of Arnold of Rugby, and therewith her intellectual ability and the force of her character are thought to be sufficiently explained. But what of her mother, the beautiful Julia Sorell, of whom her sad husband said at her death that she had “the nature of a queen,” ever thwarted and rebuffed by circumstance? What of the strain of Spanish Protestant blood that ran in the veins of the Sorells: for although they were refugees from France after the Edict of Nantes, it is most probable that they came of Spanish origin? What of the strain brought in by the wild and forcible Kemps of Mount Vernon in Tasmania? A daughter of Anthony Fenn Kemp (himself a “character” of a remarkable kind) married William Sorell and so became the mother of Julia and the grandmother of Mary Arnold; but the principal fact that is known of her is that she deserted her three daughters after bringing them to England for their education, went off with an army officer and was hardly heard of more. An ungovernable temper seems to have marked most of this family, and the recollections of her childhood were so terrible to Julia Sorell that she wrote in after years to her husband, “Few families have been blessed with such a home training as yours, and certainly very few in our rank of life have been cursed with such as mine.” Yet although Julia inherited much of this violence and passion, to her own constant misery, she had also “the nature of a queen,” and transmitted it in no small degree to her daughter Mary.

The Sorells were descended from Colonel William Sorell, one of the early Governors of Tasmania, who had been appointed to the post in 1816. Nine years before, on his appointment as Adjutant-General at the Cape of Good Hope, this Colonel Sorell had left behind him in England a woman to whom he was legally married and by whom he had had several children, but whom he never saw again after leaving these shores. He occupied himself, indeed, with another lady, while the unfortunate wife at home struggled to maintain his children on the very inadequate allowance which he had granted her. Twice the allowance lapsed, with calamitous results for the wife and children, and it was only on the active intervention of Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, that the payment of her quarterly instalments was resumed in 1818. Meanwhile, her eldest son William, a steady, hard-working lad, had been trying to support the family from his own earnings of 12s. a week, and when he grew to man’s estate he applied to Lord Bathurst for permission to join his father in Van Diemen’s Land, hoping that so he might help to reconcile his parents. Lord Bathurst gave him his passage out, but had in fact already decided to recall Governor Sorell, so that when young Sorell arrived at Hobart Town early in 1824 he found his father only awaiting the arrival of his successor (the well-known Colonel Arthur), before quitting the Colony for good. William, however, decided to remain there, accepted the position of Registrar of Deeds from Colonel Arthur, and made his permanent home in the island. He married the head-strong Miss Kemp, and in his sad after-life suffered a reversal of the parts played by his own father and mother. Long after his wife had deserted him he lived on in Hobart Town, much respected and beloved, and remembered by his granddaughter as a “gentle, affectionate, upright being, a gentleman of an old, punctilious school, content with a small sphere and much loved within it.”

His daughter Julia grew up as the favourite and pet of Hobart Town society, much admired by the subalterns of the solitary battalion of British troops that maintained our prestige among the convicts and the “blacks” of that remote settlement. But for her Fate held other things in store. Early in 1850 there appeared at Hobart Town a young man of twenty-six, tall and romantic-looking, who bore a name well known even in the southern seas—the name of Thomas Arnold. He was the second son of Dr. Arnold of Rugby. He had left the Old World for the Newest three years before on a genuine quest for the ideal life; had tried farming in New Zealand, but in vain, and had then, after some adventures in schoolmastering, come to Tasmania at the invitation of the Governor, Sir William Denison, to organize the public education of the Colony. Fortune seemed to smile upon the young Inspector of Schools, who as a first-classman and an Arnold found a kind and ready welcome from those who reigned in Tasmania, and when he met Julia Sorell a few weeks after he landed and fell in love with her at first sight, no obstacles were placed in his way. They were married on June 12, 1850—a love-match if ever there was one, but a match that was too soon to be subjected to that most fiery test of all, a religious struggle of the deepest and most formidable kind.

Thomas Arnold came of a family to whom religion was always a “concern,” as the Quakers call it; whether it was the great Doctor, with his making of “Christian gentlemen” at Rugby and his fierce polemics against the “Oxford malignants,” or Matt, with his “Power, not ourselves, that makes for righteousness,” or William (a younger brother), with his religious novel, Oakfield, about the temptations of Indian Army life; and Thomas was by no means exempt from the tradition. A sentimental idealist by nature, he was a friend of Clough and had already been immortalized as “Philip” in the Bothie of Tober-na-Vuolich.[1] He came now to the Antipodes in rationalistic mood and in search of the nobler, freer life; but soon the old beliefs reasserted themselves, yet brought no peace. His mind was “hot for certainties in this our life,” and he had not been five years in Tasmania before he was seeing much of a certain Catholic priest and feeling himself strongly drawn towards the ancient fold. His poor wife, in whom her Huguenot ancestry had bred an instinctive and invincible loathing for Catholicism, felt herself overtaken by a kind of black doom; she made wild threats of leaving him, she shuddered at the thought of what might happen to the children. Yet nothing that she or any of his friends could say might avert the fatal step. Tom Arnold was received into the Roman Catholic Church at Hobart Town on January 12, 1856.

His prospects immediately darkened, for feeling ran high in the Colony against Popery, and it soon became clear that he must give up his appointment and return to England. Already three children had been born to him and Julia, but the young wife was now plunged in preparations for the uprooting of her household and the transport of the whole family across the globe, to an unknown future and a world of unknown faces. The voyage was accomplished in a sailing-ship of 400 tons, the William Brown, so overrun by rats that the mother and nurse had to take turns to watch over the children at night, lest their faces should be bitten; but after more than three months of this existence the ship did finally reach English waters and cast anchor in the Thames on October 17, 1856. It was wet autumn weather and the little family huddled forlornly in a small inn in Thames Street, but the next day a deliverer appeared in the person of William Forster (the future Education Minister), who had married Tom’s eldest sister Jane a few years before and who now carried off the whole family to better quarters in London, helped them in the kindest way and finally saw off the mother and children to the friendly shelter of Fox How—that beloved home among the Westmorland hills which “the Doctor” had built to house his growing family and which was now to play so great a part in the development of his latest descendant, the little Mary Arnold.

Mary Augusta had been born at Hobart Town on June 11, 1851. She was, of course, the apple of her parents’ eyes, and the descriptions which her father wrote of her, in the long letters that went home to his mother at Fox How by every available boat, give a curiously vivid picture of a little creature richly endowed with fairy gifts, but above all with the crowning gift of life. At first she is a “pretty little creature, with a compact little face, good features and an uncommonly large forehead”; then at eight months, “If you could but see our darling Mary! The vigour of life, the animation, the activity of eye and hand that she displays are astonishing. Her brown hair in its abundance is the admiration of everybody.” At a year old she is “passionate but not peevish, sensitive to the least harshness in word or gesture, but usually full of merriment and gladsomeness. She is like a sparkling fountain or a gay flower in the house, filling it with light and freshness.” She has many childish ailments, but conquers them all in a manner strangely prophetic of her later power of resisting illness. “I fear you will think she must be a very sickly child,” writes her father, “and she certainly is delicate and easily put out of order; but I have much faith in the strength of her constitution, for in all her ailments she has seemed to have a power of battling against them, a vitality that pulls her through.” As a little thing of under two her feelings are terribly easily worked upon: “The other evening it was raining very hard and I began to talk to her about the poor people out in the rain who were getting wet and had no warm fire to sit by and no nice dry clothes to put on. You cannot imagine how this touched her. She kept on repeating over and over again, ‘Poor people! Poor people! Out in the rain! Get warm! get warm!’” But as she grows bigger she develops a will of her own that sorely troubles her father, beset with all the ideas of his generation about “prompt obedience”; at three and a half he writes: “Little Polly is as imitative as a monkey and as mischievous; self-willed and resolute to take the lead and have her own way, whenever her companions are anything approaching to her own age. Not a very easy character to manage as you will see, yet often to be led through her feelings, when it would be difficult to drive her in defiance of her will.” Soon he is having “a regular pitched battle with her about once a day,” and writes ruefully home—as though he were having the worst of it—that Polly is “kind enough where she can patronize, but her domineering spirit makes even her kindness partake of oppression.” Two little brothers, Willie and Theodore, had already been added to the family by the time they made the voyage home—playthings whom Mary alternately slapped and cuddled and in whom she took an immense pride of possession. They were the first of a long series of brothers and sisters to whom her kindness, in after years, was certainly not of the kind that “partakes of oppression.”

Thus, at the age of five, this little spirit, passionate, self-willed and tender-hearted, came within the direct orbit of the Arnold family. During most of the four years that followed their arrival she was either staying with her grandmother, the Doctor’s widow, at Fox How, or else living as a boarder at Miss Clough’s little school at Eller How, near Ambleside, and spending her Saturdays at Fox How. Her father meanwhile took work under Newman in Dublin and earned a precarious subsistence for his wife and family by teaching at the Catholic University there. They were times of hardship and privation for Julia, who never ceased to be in love with Tom and never ceased to curse the day of his conversion; and as the babies increased and the income did not she was fain to allow her eldest daughter to live more and more with the kind grandmother, who asked no better than to have the child about the house. And, indeed, to have this particular child about the house was not always a light undertaking! She was wonderfully quick, clever and affectionate, but her tempers sometimes shook her to pieces in storms of passion, and the devoted “Aunt Fan,” the Doctor’s youngest daughter, who lived with her mother at Fox How, was often sorely puzzled how to deal with her. Still, by a judicious mixture of severity and tenderness she won the child’s affection, so that Mary was wont to say, looking slyly at her aunt, “I like Aunt Fan—she’s the master of me!”

The Arnold atmosphere made indeed a very remarkable influence for any impressionable child of Mary’s age to live in; it supplied a deep-rooted sense of calm and balance, an unalterable family affection and a sad disapproval of tempers and excesses of all kinds which, as time went on, had a marked effect on the Tasmanian child. From a Sorell by birth and temperament, as I believe she was, she gradually became an Arnold by environment. If she inherited from her mother those wilder springs of energy and courage which impelled her, like some dæmon within, to be up and doing in life’s race, it was from the Arnolds that she learnt the art of living, the art of harnessing the dæmon. They certainly made a memorable group, the nine sons and daughters of Arnold of Rugby: all of whom, except Fan, the youngest daughter, were scattered from the nest by the time that “little Polly” came to Fox How, but all of whom maintained for each other and for their mother the tenderest affection, so that life at the Westmorland home was continually crossed and re-crossed by their visits and their letters. In looking through these faded letters the reader of to-day is struck by their seriousness and simplicity of tone, by the intense family affection they display and by the very real relation in which the writers stood towards the “indwelling presence of God.” Hardly a member of the family can be mentioned without the prefix “dear” or “dearest,” nor can anyone who is acquainted with the Arnold temperament doubt that this was genuine. Birthdays are made the occasion for rather solemn words of love or exhortation, and if any sorrow strikes the family one may expect without fail to find a complete reliance on the accustomed sources of consolation. Yet they are not prigs, these brothers and sisters; their roots strike deep down to the bed-rock of life, and though they are all (except poor Tom) in fairly prosperous circumstances, they can be generous and open-handed to those who are less so. Tom was, I think, the special darling of the family, and his lapse to Catholicism a terrible trial to them, but none the less did they labour for Tom’s children in all simplicity of heart.

The daughter who, next to “Aunt Fan,” had most to do with little Mary was Jane, the wife of William Forster; Mary was her godchild, and soon conceived a kind of passion for this sweet-faced woman of thirty-five, who, childless herself, returned the little girl’s affection in no ordinary degree. Mary would sometimes go to stay with her at Burley-in-Wharfedale, where she looked with awe at the “great wheels” in Uncle Forster’s woollen mill and saw the children working there—children untouched as yet by their master’s schemes for their welfare, or by the still remoter visions of their small observer. Then there was Matt—Matt the sad poet and gay man of the world, who brought with him on his rarer visits to Fox How the breath of London and of great affairs, for was he not, in his sisters’ eyes at least, the spoilt darling of society, the diner-out, the frequenter of great houses? He looked, we know, with unusual interest upon Tom’s Polly, and in later years was wont to say, with his whimsical smile, that she “got her ability from her mother.” Another aunt to whom the Tasmanian child became much devoted was her namesake Mary, at that time Mrs. Hiley, a woman whose rich, responsive nature and keen sense of humour endeared her greatly to the few friends who knew her well, and whose early rebellions and idealisms had given her a most human personality. It was she among all the group who understood and sympathized most keenly with Tom’s wife, so that between Julia and Mary Hiley a bond was forged that ended only with the former’s death. Poor Julia! The Arnold atmosphere was indeed sometimes a formidable one, and had little sympathy to give to her own undisciplined and tempestuous nature, with its strange deeps of feeling. Julia’s temptations—to extravagance in money matters and to passionate outbursts of temper—were not Arnold temptations, and she often felt herself disapproved of in spite of much outward affection and kindness. And then she would have morbid reactions in which the old Calvinistic hell-fire of her forefathers seemed very near. Once when she was staying at Fox How, ill and depressed, she wrote to her husband: “The feeling grows upon me that I am one of those unhappy people whom God has abandoned, and it is the effect of this feeling I am sure which causes me to behave as I often do. Oh! it is an awful thing to despair about one’s future state....” Probably she felt that in spite of their undoubted humility, her in-laws never quite despaired about theirs.

By the time that Mary was seven years old, that is in the autumn of 1858, it was decided that she should go as a boarder to Miss Anne Clough’s school at Ambleside, or rather at Eller How on the slopes of Wansfell behind the town. Here she spent two years and more—happy on the whole, often naughty and wilful, but usually held in awe by Miss Clough’s stately presence and power of commanding her small flock. There was only one other boarder besides Mary, a girl named Sophie Bellasis, whose recollections of those days were preserved and given to the world long afterwards by her husband, the late Mr. T. C. Down, in an article published by the Cornhill Magazine.[2] Miss Bellasis’ impressions of the queer little girl, Mary Arnold, who was her fellow-boarder, make so vivid a picture that I may perhaps be forgiven for reproducing them here:

“Mary had a very decided character of her own, as well as a pretty vivid imagination, for the odd things she used to say, merely on the spur of the moment, would quite stagger me sometimes. Once when we were going along the passage upstairs leading to the schoolroom, she stopped at one of the gratings where the hot air came up from the furnace, with holes in the pattern about the size of a shilling, and told me that she knew a little boy whose head was so small that he could put it through one of those holes: and after we had gone to bed she would tell me the oddest stories in a whisper, because it was against the rules to talk. I think now that her fancy used to run riot with her, and, of course, she had to give vent to it in any way that suggested itself. But I implicitly believed whatever she chose to tell me, so that you see we both enjoyed ourselves. Her energy and high spirits were something wonderful; out of doors she was never still, but always running or jumping or playing, and she invariably tired me out at this sort of thing. Still, nothing came amiss to her in the way of amusement; anything that entered her head would answer the purpose, and she was never at a loss. I recollect she had a lovely doll, which her aunt, Mrs. Forster, had given her, all made of wax. Once she was annoyed with this doll for some reason or other and broke it up into little bits. We put the bits into little saucepans, and melted them over one of the gratings I told you of. Sometimes Willy Dolly (that was the name we had for the general factotum) would let the fire go down, and then the gratings were cold, and at other times he would have a roaring fire, and then they would be so hot that you couldn’t touch them. So we melted the wax and moulded it into dolls’ puddings, and that was the last of her wax doll!

“One day we were over at Fox How, which was a pretty house, with a wide lawn and garden. One side of it was covered with a handsome Virginia creeper, which was thought a great deal of, and, of course, was not intended to be meddled with. Suddenly it occurred to Mary that it would be first-rate fun to pick ‘all those red leaves,’ and I obediently went and helped her. We cleared a great bare space all along the wall as high as we could reach, but from what Miss Arnold said when she came out and discovered what was done, I gathered that she was not so pleased with our work as we were ourselves.”

It was during these years, from six to nine, that the foundation was laid of that passionate adoration for the fells, with their streams, bogs and stone walls, which became one of Mary’s most intimate possessions and never deserted her in after years. In her Recollections she describes a walk up the valley to Sweden Bridge with her father and Arthur Clough, the two men safely engaged in grown-up talk while she, happy and alone, danced on in front or lingered behind, all eyes and ears for the stream, the birds and the wind. It was a walk of which she soon knew every inch, just as she knew every inch of the Fox How garden, and I believe that the sights and sounds of that rough northern valley came to be woven in with the very texture of her soul. They appealed to something primitive and deep-down in her little heart, some power that remained with her through life and that, as she once said to me, “stands more rubs than anything else in our equipment.”

Then, when she was only nine and a half, she was transferred to a school at Shiffnal in Shropshire, kept by a certain Miss Davies, whose sister happened to be an old friend of Tom Arnold’s and offered now to undertake little Mary’s maintenance if she were sent to this “Rock Terrace School for Young Ladies.” But the change seemed to call out all the demon in Mary’s composition; she fought blindly against the restrictions and rules of this new community, felt herself at enmity with all the world and broke out ever and anon in storms of passion. In the first chapter of Marcella it is all described—the “sulks, quarrels and revolts” of Marcie Boyce (alias Mary Arnold), the getting up at half-past six on dark winter mornings, the cold ablutions and dreary meals, and the occasional days in bed with senna-tea and gruel when Miss Davies (at her wits’ end, poor lady!) would try the method of seclusion as a cure for Mary’s tantrums. The poor little thing suffered cruelly from headaches and bad colds, and laboured too under a sore sense of poverty and disadvantage as compared with the other girls; she was, in fact, paid for at a lower rate than most of the other boarders, and was not allowed to forget it. Often she writes home to beg for stamps, and once she says to her father: “Do send me some more money. It was so tantalizing this morning, a woman came to the door with twopenny baskets, so nice, and many of the other girls got them and I couldn’t.” Another time she begs him to send her the threepence that she has “earned,” by writing out some lists of names for him. But on Saturdays she had one joy, fiercely looked forward to all the week; a “cake-woman” came to the school, and by hoarding up her tiny weekly allowance she was able—usually—to buy a three-cornered jam puff. To a rather starved and very lonely little girl of nine or ten this was—she often said to us afterwards—the purest consolation of the week.

But there were some compensations even in these unlovely surroundings. The nice old German governess, Fräulein Gerecke, was always kind to her, and tried in little unobtrusive ways to ease the lot which Mary found so hard to bear. Once she made for her, surreptitiously, a white muslin frock with blue ribbons and laid it on her bed in time for some little function of the school for which Mary had received no “party frock” from home. A gush of hot tears was the response, tears partly of gratitude, partly of soreness at the need for it; but the muslin frock was worn nevertheless, and entered from that moment into the substance of the day-dreams and stories that she was for ever telling herself. Any child who has a faculty for it will understand how great a consolation were these self-told stories, in which she rioted especially on days of senna-tea and gruel. Tales of the Princess of Wales and how she, Mary, herself succeeded in stopping her runaway horses, with the divinity’s pale agitation and gratitude, filled the long hours, and the muslin frock usually came into the story when Mary made her trembling appearance “by command” at the palace afterwards. Gradually, too, these tales came to weave themselves round more accessible mortals, for Mary’s heart and affections were waking up and she did not escape, any more than the modern schoolgirl, her share of “adorations.” At twelve years old she fell headlong in love with the Vicar of Shiffnal and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Cunliffe; going to church—especially in the evenings, when the Vicar preached—became a romance; seeing Mrs. Cunliffe pass by in her pony-carriage lent a radiance to the day. The Vicar’s wife, a gentle Evangelical, felt genuinely drawn towards the untamed little being and did her best to guide the wayward footsteps, while Mary on her side wrote poems to her idol, keeping them fortunately locked within her desk, and let her fancy run from ecstasy to ecstasy in the dreams that she wove around her. What “dauntless child” among us does not know these splendours, and the transforming effect that they have upon the prickly hide of youth? Little Mary Arnold was destined to leave her mark upon the world, partly by power of brain, but more by sheer power of love, and the first human beings to unlock the unguessed stores of it within her were these two kindly Evangelicals.

Still, the demon was not quite exorcised, and “Aunt Fan” still found Mary something of a handful when she stayed at Fox How, though now in a different way.

“She seems to me very much wanting in humility,” she writes in January, 1864, “which, with the knowledge she must have of her own abilities, is not perhaps wonderful, but it is ungraceful to hear her expressing strong opinions and holding her own, against elder people, without certainly much sense of reverence. One thing, however I will mention to show her desire to conquer herself. She had no gloves to go to Ellergreen, and I objected to buying her kid, but got her such as I wear myself, very nice cloth. She vowed and protested she couldn’t and shouldn’t wear them, so I said I should not make her, but if she wanted kid, she must buy them with her own money. I talked quietly to her about it and said how pleased I should be if she conquered this whim, and when she came to say good-bye to me before starting for Ellergreen her last words were—‘I am going to put on the gloves, Auntie!’—and she has worn them ever since, though I must say with some grumblings!”

She stayed for four years at Miss Davies’s, during which time her parents moved (in 1862) from Dublin to Birmingham, where Tom Arnold was offered work under Newman at the Oratory School. The change brought a small increase in salary, but not enough to cover the needs of the still growing family, and if it had not been for the help freely given during these years by W. E. Forster, the struggling pair must almost have gone down under their difficulties. One result of the change was that the elder boys, Willie and Theodore, were themselves sent to the Oratory School, and the thought of Arnold of Rugby’s grandsons being pupils of Newman gave rise to bitter reflections at Fox How. “I was very glad to hear of Willy’s having done so well in the examination of his class,” wrote Julia to her husband from the family home, “although I must confess the thought of our son being examined by Dr. Newman had carried a pang to my heart. Your mother I found felt it in the same way; she said (when I read out to her that part of your letter) with her eyes full of tears, ‘Oh! to think of his grandson, dearest Tom’s son, being examined by Dr. Newman!’” Still, Julia was emphatically of opinion that if priests were to have a hand in their education at all, she would rather it were English than Irish priests.[3]

Meanwhile, the shortcomings of the school at Shiffnal were becoming evident to Mary’s mother, and in the winter of 1864-5 she succeeded in arranging that the child should be sent instead to another near Clifton, kept by a certain Miss May, which was smaller and also more expensive than Miss Davies’s. Heaven knows how the payments were managed, but the change answered extremely well, for after the first term Mary settled down in complete happiness and soon developed such a devotion to Miss May as made short work of her remaining tendencies to temper and “contrariness.” Miss May must have been exactly the type of schoolmistress that Mary needed at this stage—kind and large-hearted, with the understanding necessary to win the confidence of such an uncommon little creature—so that it was not long before the child’s mind began to expand in every direction. Long afterwards she was wont to say that the actual knowledge she acquired at school was worth next to nothing—that she learnt no subject thoroughly and left school without any “edged tools.” But certainly by the time she was twelve she could write a French letter such as not many of us could produce with all our advantages, while the drawing and music that she learnt at school encouraged certain natural talents in her that were to give her some of the purest joys of her after-life. Still, no doubt her mind received no systematic training, and at Miss Davies’s I believe that Mangnall’s Questions were still the common textbook! Though she learnt a little German and Latin she always said that she had them to do all over again when she needed them later for her work, while Greek, which became the joy and consolation of her later years, was entirely a “grown-up” acquisition. But whatever the imperfections of her nine years of school, better times were at hand both for Mary and her mother.

Whether it was that after two or three years of the Birmingham Oratory, Tom Arnold’s political radicalism (always a sturdy growth) began to make him uneasy at the proceedings of Pio Nono—for 1864 was the year of the Encyclical—or whether it was more particularly the Mortara case, as he says in his autobiography,[4] at any rate his feeling towards the Catholic Church had grown distinctly cool by the end of that year, and he was meditating leaving the Oratory. Gradually the rumour spread among his friends that Tom Arnold was turning against Rome, and in June, 1865, a paragraph to this effect appeared in the papers. Little Mary, now a girl of fourteen, heard the news while she was at Miss May’s, and wrote in ecstasy to her mother:

‘My precious Mother, I have indeed seen the paragraphs about Papa. The L’s showed them me on Saturday. You can imagine the excitement I was in on Saturday night, not knowing whether it was true or not. Your letter confirmed it this morning and Miss May, seeing I suppose that I looked rather faint, sent me on a pretended errand for her notebook to escape the breakfast-table. My darling Mother, how thankful you must be! One feels as if one could do nothing but thank Him.”

Her father’s change opened indeed a new and happier chapter in their lives, for it opened the road to Oxford. He had been seriously facing the possibility of a second emigration, this time to Queensland, and had been making inquiries about official work there, but his own inclinations—and, of course, Julia’s too—were in favour of trying to make a living at Oxford by the taking of pupils. His old friends there encouraged him, and by the autumn of 1865 they were established in a house in St. Giles’s and the venture had begun. Mary wrote in delight that winter to her dear Mrs. Cunliffe:

“Do you know that we are now living at Oxford? My father takes pupils and has a history lectureship. We are happier there than we have ever been before, I think. My father revels in the libraries, and so do I when I am at home.”

A fragment of diary written in the Christmas holidays of 1865-6 reveals how much she enjoyed being taken for a grown-up young lady by Oxford friends. “Went to St. Mary Magdalen’s in the morning and heard a droll sermon on Convictional Sin. Met Sir Benjamin [Brodie] coming home. Miss Arnold at home supposed to be seventeen, and Mary Arnold at school known to be fourteen are two very different things.” She is absorbed in Essays in Criticism, but can still criticize the critic. “Read Uncle Matt’s Essay on Pagan and Mediaeval Religious Sentiment. Compares the religious feeling of Pompeii and Theocritus with the religious feeling of St. Francis and the German Reformation. Contrasts the religion of sorrow as he is pleased to call Christianity with the religion of sense, giving to the former for the sake of propriety a slight pre-eminence over the latter.” She does not like the famous Preface at all. “The Preface is rich and has the fault which the author professes to avoid, that of being amusing. As for the seductiveness of Oxford, its moonlight charms and Romeo and Juliet character, I think Uncle Matt is slightly inclined to ride the high horse whenever he approaches the subject.”

As the eldest of eight children she led a very strenuous life at home, helping to teach the little ones and ever striving to avoid a clash between her mother’s temper and her own. The entries in the diary are often sadly self-accusing: “These last three days I have not served Christ at all. It has been nothing but self from beginning to end. Prayer seems a task and it seems as if God would not receive me.”

But after another year and a half at Miss May’s school these difficulties vanished, and by the time that she came to live at home altogether, in the summer of 1867, the rough edges had smoothed themselves away in marvellous fashion. She was sixteen, and the world was before her—the world of Oxford, which in spite of her criticisms of the Preface was indeed her world. Her father seemed content with his teaching work, and was planning the building of a larger house. She set to work to be happy, and so indeed did her mother—happy in a great reprieve, and in the reviving hopes of prosperity. But now and then Julia would stop suddenly in her household tasks, hearing ominous sounds from Tom’s study. Was it the chanting of a Latin prayer? She put the fear behind her and passed on.

WHEN Tom Arnold settled with his family at Oxford, in 1865, the old University was still labouring under the repercussions, the thrills and counter-thrills, of the famous Movement set on foot in 1833 by Keble’s sermon on National Apostasy. Keble, indeed, was withdrawn from the scene, but Newman’s conversion to Rome (1845) had made so prodigious a stir that even twenty years later the religious world of England still took its colour from that event. In the words of Mark Pattison, “whereas other reactions accomplished themselves by imperceptible degrees, in 1845 the darkness was dissipated and the light was let in in an instant, as by the opening of the shutters in the chamber of a sick man who has slept till mid-day.” So at least the crisis appeared to the Liberal world; the mask had been torn from the Tractarians and their Romanizing tendencies stood revealed to all beholders. In the opposite camp the consternation was proportionate, but the formidable figure of Pusey rallied the doubters and brought them back in good order to the Via Media of the Anglican communion; while the tender poetry of Keble and the far-famed eloquence of Liddon fortified and adorned the High Church cause. But the sudden ending of the Tractarian controversy opened the way for another movement, slower and less sensational than that of Newman, yet destined to have an even deeper effect upon the religious life of England. The freedom of the human mind began to be insisted upon, not only in the realm of science, or where science clashed with the Book of Genesis, but in the whole field of the Interpretation of Scripture. Slowly the results of fifty years of patient study of the Bible by German scholars and historians began to penetrate here, and even Oxford, stronghold and citadel of the Laudian establishment, felt the stir of a new interest, a new challenge to accepted forms. A Liberal school of theologians arose, led by Jowett, Mark Pattison and other writers in Essays and Reviews (1860), for whom the old letter of “inspiration” no longer existed, though they stoutly maintained their orthodoxy as members and ministers of the Church of England. The Church, they said, must broaden her base so as to make room for the results of science and of historical criticism, or else she would be left high and dry while the forces of democracy passed on their way without her. Jowett, in his famous essay “On the Interpretation of Scripture,” boldly summed up his argument in the precept, “Interpret the Scripture like any other book.” “The first step is to know the meaning, and this can only be done in the same careful and impartial way that we ascertain the meaning of Sophocles or Plato.” “Educated persons are beginning to ask, not what Scripture may be made to mean, but what it does mean.”

The hubbub raised by these and similar expressions continued during the three years of proceedings before the Court of Arches, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, and finally Convocation, against two of the contributors to Essays and Reviews, and had hardly died away when the Arnolds came to take up their life in Oxford. And side by side with the theoretical discussion went the insistent demand of the reforming party, both at Oxford and in Parliament, for the abolition of the disabilities that still weighed so heavily against Dissenters. For, although the “Oxford University Act” of 1854 had admitted them to matriculation and the B.A. degree, neither Fellowships nor the M.A. were yet open to any save subscribers to the Thirty-nine Articles. All through the ’sixties the battle raged, with an annual attempt in Parliament to break down the defence of the guardians of tradition, and not till 1871 was the “citadel taken.”[5] Jowett and Arthur Stanley stood forth among the Liberal champions at Oxford—the latter reckoning himself always as carrying on the tradition of Arnold of Rugby, whose pamphlet urging the inclusion of Dissenters in the National Church had made so great a sensation in 1833. It was hardly possible, therefore, for a little Arnold of Mary’s temperament and traditions to escape the atmosphere that surrounded her so closely, though we need not imagine that at the age of sixteen she did more than imbibe it passively. But there were certain things that were not passive in her memory—visions of Dr. Newman in the streets of Edgbaston, passing gravely by upon his business—business which the child so passionately resented because she understood it to be responsible in some vague way for all the hardships and misfortunes of her family. We may safely assume that if she was ever taken into Oriel College and saw the many rows of portraits looking down at her there, in Common-room and Hall, she would feel an instinctive rallying to the standard of her grandfather rather than to that of his mighty opponent.

Two other remarkable figures who dominated the Oxford world of that day, though from opposite camps, were the silver-tongued Dr. Liddon, “Select Preacher” at the University Church, and Mark Pattison, Rector of Lincoln, whom his contemporaries looked on with awe as one of the most learned scholars in Europe in matters of pure erudition, but in religion a sad sceptic, though twenty years before, they knew, he had been a brand only barely plucked from Newman’s burning. Both were to have their influence upon Mary Arnold, the former superficial, the latter deep and lasting, and it is curious to find a letter from her father, written in 1865, before he had definitely left the Catholic communion, in which he describes hearing both men preach on the same day in the University Church.

“Pattison’s sermon was certainly a most remarkable one,” he writes; “I could have sat another half-hour under him with pleasure. But he has much more of the philosopher than the divine about him, and the discourse had the effect of an able article in the National or Edinburgh Review, read to a cultivated audience in the academical theatre, much more than of a sermon. In fact, the name either of Jesus Christ or of one of the Apostles was not once mentioned throughout. The subject was, the higher education; and the felicity of the language accorded well with the clearness and beauty of the thoughts. He condemned the Catholic system, and also the Positivist system, and in speaking of the former he said, ‘I cannot do better than describe it in the words of one whose voice was once wont to sound within these walls with thrilling power, but now, alas! can never more be heard by us, who in his Treatise on University Education—‘ and then he proceeded to quote at some length from Dr. Newman. It was an extremely powerful sermon, but scandalized, I think, the High Church and orthodox party. ‘Do you often now,’ I asked Edwin Palmer with a smile, meeting him outside after it was over, ‘have University sermons in that style?’ ‘Oh dear no,’ he said, ‘scarcely ever, except indeed from Pattison himself’; this with some acidity of tone. I dined early; then thought I, in for a penny, in for a pound, I’ll go and hear the other University sermon. I was punctual, but there was not a seat to be had, the ladies mustered in overwhelming force. It was strange, but sermon and preacher were now everything most opposite to those of the morning. Liddon is a dark, black-haired little man—short, straight, stubby hair—and with that shiny, glistening appearance about his sallow complexion which one so often sees in Dissenting ministers, and which the devotees no doubt consider a mark of election. Liddon’s whole sermon was an impassioned strain of apologetic argument for the truth of the Resurrection, and of the church doctrine generally. It was very clever certainly, but rather too long, it extended to about an hour and twenty minutes. The tone was earnest and devout; yet there were several sarcastic, one might almost say irritable, flings at the liberal and rationalizing party; and it was evident that he was thinking of the Oxford congregation when he spoke pointedly of the ‘educated sceptics who at that time composed, or at any rate controlled, the Sanhedrin.’ These two,” he continues, “were certainly sermons of more than ordinary interest—each worthily representing a great stream of thought and tendency, influential for good or evil at the present moment upon millions of human beings.”

It was under such influences as these that Mary Arnold passed the four impressionable years of her girlhood, from sixteen to twenty, that elapsed between her leaving school and her engagement to Mr. Humphry Ward, of Brasenose. She plunged with zest into the Oxford life, making friends, helping her father at the Bodleian in his researches into early English literature and studying music to very good purpose under James Taylor, the future organist of New College. But she had no further regular education, and was free to roam and devour at will in that city of books, guided only by the advice of a few friends and by her own innate literary instincts. The Mark Pattisons early befriended her, frequently asking her to supper with them on Sunday evenings—suppers at which she sat, shy and silent, in a high woollen dress, with her black, wavy hair brushed very smoothly back, listening to every word of the eager talk around her and drinking in, no doubt, the Rector’s caustic remarks about Oxford scholarship. These were the years of battle between the champions of research and the champions of the Balliol ideal of turning out good men for the public service, and in her ardent admiration for the Rector Mary Arnold threw herself whole-heartedly into the former camp. “Get to the bottom of something,” he used to say to her; “choose a subject and know everything about it!” And so she plunged into early Spanish literature and history, working at it in the Bodleian with the fervour that comes from knowing that your subject is your very own, or at least that it has only been traversed before by dear, musty German scholars. There was hard practice here in the reading of German and Latin, let alone the Spanish poems and chronicles themselves, but after a couple of years of it there was little she did not know about the Poema del Cid, or the Visigothic invasion, or the reign of Alfonso el Sabio. Her friend, J. R. Green, the historian, was so much impressed with her work that he recommended her when she was only twenty to Edward Freeman as the best person he could suggest for writing a volume on Spain in an historical series that the latter was editing. Mr. Freeman duly invited her, but by that time she was already deep in the preparations for her marriage and was obliged to decline the offer. She maintained her allegiance to the subject, however, through all the years that followed, until, as will be seen hereafter, Dean Wace made her the momentous proposition that she should undertake the lives of the early Spanish kings and ecclesiastics for the Dictionary of Christian Biography. And there, in the four volumes of the Dictionary, her articles stand to this day, a monument to an early enthusiasm lightly kindled by a word from a great man, but pursued with all the patience and intensity of the true historian.

In the course of this work on the early Spaniards she developed an extraordinary attachment to the Bodleian, with all the most secret corners of which she soon became familiar, under the benevolent guidance of the Librarian, Mr. Coxe. The charm of the noble building, with its mellow lights and shades, its silences, its deep spaces of book-lined walls, sank into her very soul and gave her that background of the love of books and reading which became perhaps—next to her love of nature—the strongest solace of her after-life. At the age of twenty she wrote a little essay, called “A Morning in the Bodleian,”[6] which reflects all the joy—nay, the pride—of her own long days of work among the calf-bound volumes.

“As you slip into the chair set ready for you,” she writes, “a deep repose steals over you—the repose, not of indolence but of possession; the product of time, work and patient thought only. Literature has no guerdon for ‘bread-students,’ to quote the expressive German phrase; let not the young man reading for his pass, the London copyist or the British Museum illuminator, hope to enter within the enchanted ring of her benignest influences; only to the silent ardour, the thirst, the disinterestedness of the true learner, is she prodigal of all good gifts. To him she beckons, in him she confides, till she has produced in him that wonderful many-sidedness, that universal human sympathy which stamps the true literary man, and which is more religious than any form of creed.”

A touch about the German students to be found there has its note of prophecy: “In a small inner room are the Hebrew manuscripts; a German is working there, another in shirt-sleeves is here—strange people of innumerable tentacles, stretching all ways, from Genesis to the latest form of the needle-gun.” And in the last page we come upon her most intimate reflections, the thoughts pressed together from her many months of comradeship with those silent tomes, which show, better than any letters, the quality of a mind but just emerging—as the years are reckoned—from its teens:—

“Who can pass out of such a building without a feeling of profound melancholy? The thought is almost too obvious to be dwelt upon; but it is overpowering and inevitable. These shelves of mighty folios, these cases of laboured manuscripts, these illuminated volumes of which each may represent a life—the first, dominant impression which they make cannot fail to be like that which a burial-ground leaves—a Hamlet-like sense of ‘the pity of it.’ Which is the sadder image, the dust of Alexander stopping a bung-hole, or the brain and life-blood of a hundred monks cumbering the shelves of the Bodleian? Not the former, for Alexander’s dust matters little where his work is considered, but these monks’ work is in their books; to their books they sacrificed their lives, and gave themselves up as an offering to posterity. And posterity, overburdened by its own concerns, passes them by without a look or a word! Here and there, of course, is a volume which has made a mark upon the world; but the mass are silent for ever, and zeal, industry, talent, for once that they have had permanent results, have a thousand times been sealed by failure. And yet men go on writing, writing; and books are born under the shadow of the great libraries just as children are born within sight of the tombs. It seems as though Nature’s law were universal as well as rigid in its sphere—wide wastes of sand shut in the green oasis, many a seed falls among thorns or by the wayside, many a bud must be sacrificed before there comes the perfect flower, many a little life must exhaust itself in a useless book before the great book is made which is to remain a force for ever. And so we might as profitably murmur at the withered buds, at the seed that takes no root, at the stretch of desert, as at the unread folios. They are waste, it is true; but it is the waste that is thrown off by Humanity in its ceaseless process towards the fulfilment of its law.”

No doubt her life was not all books during these four years, though books gave it its tone and background; she took her part in the gaieties of Oxford, in Eights Week and Commem. and in river parties to the Nuneham woods, and it is to be feared that her stout resistance to the “seductiveness of Oxford, its moonlight charms and Romeo and Juliet character” was not of long duration. In one select Oxford pastime, the game of croquet, she attained to real pre-eminence, becoming, after her marriage, one of the moving spirits of the Oxford Croquet Club. But her shyness made social events no special joy to her, and she was far happier sitting at the feet of “Mark Pat” or helping “Mrs. Pat” with her etching in the sitting-room upstairs than in making conversation with the youth of Oxford.

One charming glimpse of her, however, at a social function remains to us in the letters of M. Taine. The great Frenchman had come over in the very spring of the Commune (1871) to give a course of lectures at Oxford; he met her one evening at the Master of Balliol’s, being introduced to her by Jowett himself. “‘A very clever girl,’ said Professor Jowett, as he was taking me towards her. She is about twenty, very nice-looking and dressed with taste (rather a rare thing here: I saw one lady imprisoned in a most curious sort of pink silk sheath). Miss Arnold was born out in Australia, where she was brought up till the age of five. She knows French, German and Italian, and during this last year has been studying old Spanish of the time of the Cid; also Latin, in order to be able to understand the mediæval chronicles. All her mornings she spends at the Bodleian Library—a most intellectual lady, but yet a simple, charming girl. By exercise of great tact, I finally led her on to telling me of an article—her first—that she was writing for Macmillan’s Magazine upon the oldest romances. In extenuation of it she said, ‘Everybody writes or lectures here, and one must follow the fashion. Besides, it passes the time, and the library is so fine and so convenient.’ Not in the least pedantic!”[7]

Mary’s efforts at writing fiction, which had been many from her school-days onwards, were far less successful at this stage than her more serious essays; but she persisted in the attempt, for the pressure on the family budget was always so great that she longed to make herself independent of it by earning something with her pen. She sent one story, at the age of eighteen, to Messrs. Smith & Elder, her future publishers, but when it was politely declined by them she showed her philosophy in the following note—

Laleham, Oxford.

October 1, 1869.

DEAR SIRS,—

I beg to thank you for your courteous letter. “Ailie” is a juvenile production and I am not sorry you decline to publish it. Had it appeared in print I should probably have been ashamed of it by and by.

I remain,

Yours obediently,

MARY ARNOLD.

But at length no less a veteran than Miss Charlotte Yonge, who was then editing a blameless magazine named the Churchman’s Companion, accepted a tale from her called “A Westmorland Story,” and Mary’s joy and pride were unbounded. But the tale shows no glimpse, I think, of her future power, and is as far removed from “A Morning in the Bodleian” as water is from wine.

Sometimes the Forsters would invite her to stay with them in London, and so it occurred that at the age of eighteen she was actually there, in the Ladies’ Gallery of the House of Commons, when her uncle brought in his famous Education Bill. In after life she was always glad to recall that day, and when in the fullness of time her own path led her among the stunted lives of London’s children she liked to think that she was in a sense continuing her uncle’s work.

In the winter of 1870-71 she first met Mr. T. Humphry Ward, Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose College, between whom and herself an instant attraction became manifest. Mr. Ward was the son of the Rev. Henry Ward, Vicar of St. Barnabas, King Square, E.C., while his mother was Jane Sandwith, sister of the well-known Army surgeon at the siege of Kars, Humphry Sandwith, and herself a woman of remarkable charm and beauty of character. By an odd chance, J. R. Green, the historian, had been curate to Mr. Henry Ward in London for two years, had made himself the devoted friend of all his numerous children and has left in his published Letters a striking tribute to the great qualities of Mrs. Ward.[8] But she died at the age of forty-two, and Mary Arnold never knew her. The course of true love ran smoothly through the spring of 1871, and on June 16, five days after Mary’s twentieth birthday, they became engaged. Never was happiness more golden, and when the pair of lovers went to stay at Fox How and the young man was introduced to all the well-beloved places—Sweden Bridge and Loughrigg, Rydal Water and the stepping-stones—she was quite puzzled, as she wrote to him afterwards, by the change that had come over the mountains, by the “new relations between Westmorland and me!” It was simply, as she said, that the mountains had become the frame, instead of being, as hitherto, the picture.

They were engaged for ten months, and then, on April 6, 1872, Dean Stanley married them and they settled, a little later, in a house in Bradmore Road (then No. 5, now 17), where they lived and worked for the next nine years.

Strenuous and delightful years! In looking back over them her old friends recall with amazement her intense vitality and energy, in spite of many lapses of health; how she was always at work, writing articles or reviewing books to eke out the family income, and how she seemed besides to bear on her shoulders the cares of two families, her own and her husband’s. She was the eldest and he the third of a long string of brothers and sisters, the younger of whom were still quite children and much in need of shepherding. The house in Bradmore Road was always a second home to them. Her own parents lived close by and she was much in and out of their house, sharing in their anxieties and struggles and helping whenever it was possible to help. For she was linked to her father by a deep and instinctive devotion, much strengthened by these years of companionship at Oxford, and to her mother by a more aching sense of pity and longing. Tom Arnold was growing restless again in the mid-’seventies, and when he went with his younger children to church at St. Philip’s they would nudge each other to hear him muttering under his breath the Latin prayers of long ago—little thinking, poor babes, how their very bread and butter might hang upon these mutterings! But in 1876 there came a day when his election to the Professorship of Early English was almost a foregone conclusion; as the author of the standard edition of Wycliffe’s English Works he was by far the strongest candidate in the field, and Julia looked forward eagerly to a time of deliverance from their perpetual money troubles. For some months, however, he had secretly made up his mind that he must re-enter the Roman fold, and now that once more his worldly promotion depended on his remaining outside it he decided that this was the moment to make his re-conversion public. He announced it on the very eve of the election, with the result that the majority of the electors decided against him. Poor Mary heard the news early next morning and ran round in great distress to her true friends, the T. H. Greens, pouring it out to them with uncontrollable tears. And, indeed, it was the death-knell of the Arnolds’ prosperity at Oxford. Pupils came no longer to be taught by a professing Catholic, and Julia was reduced to taking “boarders” in a smaller house in Church Walk, while Tom earned what he could by incessant writing and eventually took work again at the Catholic University in Dublin. And then a still more terrible blow fell upon Julia; she was discovered to have cancer, and an operation in the autumn of 1877 left her a maimed and suffering invalid. All this could not fail to leave a profound mark on the anxious and tender heart of her daughter, in whom the capacity for human affection seemed to grow and treble with the years; it made a dark background to her Oxford life, otherwise so full to overflowing with the happiness of friends and home.

In her Recollections she has given us once and for all a picture of the Oxford of her day which in its brilliance and charm is not to be matched by any later comer. All that can be attempted here is to fill in to some extent the only gap that she has left in it—the portrait of herself. How did she move among that small but gifted community, where Walter Pater revolutionized the taste of Oxford with his Morris papers and blue china, shocked the Oxford world with his paganizing tendencies and would, besides, keep his sisters laughing the whole evening, when they were quite alone, with his spontaneous fun; where Mandell Creighton was leading and stimulating the teaching of history, with J. R. Green to help him as Examiner in the Modern History Schools; where T. H. Green was inspiring the younger generation with his own robust idealism and the doctrine of the “duty of work,” and the more venerable figures of Jowett and Mark Pattison, Ruskin and Matthew Arnold, Stubbs and Freeman dominated the intellectual scene? The impression that she made upon this circle of friends seems first of all to have been one of extraordinary energy and power of work, of great personal charm veiled by a crust of shyness, of intellectual powers for which they had the respect of equals and co-workers, and of a warm and generous sympathy which was yet free from “gush.” One of her closest friends in these early years, Mrs. Arthur Johnson, has allowed me to use certain extracts from her journal, in which the figure of “Mary Ward” stands out with the clearness of absolute simplicity. Mrs. Johnson, besides having the public spirit which has since made her the President of the Oxford Home Students’ Society, was also a charming artist, and in 1876 painted Mary’s portrait in water-colour, using the opportunities which the sittings gave her to explore her friend’s mind to the uttermost:

“July 22. Began her portrait. I was so excited that my head ached all day afterwards. She talked of deep, most interesting subjects, and attention to the arguments and drawing too was too much for one’s head! I was surprised at the full extent of her vague religion. Jowett is her great admiration and Matt Arnold her guide for some things. She is great on the rising Dutch and French and German school of religious thought, very free criticism of the Bible, entire denial of miracle, our Lord only a great teacher. I felt as if I had been beaten about, as I always do after the excitement of such talks. And yet it is all a striving after righteousness, sincerity, truth.” Or, again: “Mary W. came to tea. My visitor was charmed with her and truly she is a sweet, charming person, full of gentleness and sympathy, with all her talent and intelligence too. She had dined at the Pattisons’ last night and had felt appalled at the learning of Mrs. P. and Miss ——,‘ more in their little fingers than I in my whole body!’ But I felt that no one would wish to change her for either of them.”

Her music was a constant joy to her friends, and Mrs. Johnson makes frequent mention of her playing of Bach and of her wonderful reading. It was a possession that remained with her, to a certain extent, all her life, in spite of writer’s cramp and of a total inability to find time to “keep it up.” But even twenty and thirty years later than this date, her playing of Beethoven or Brahms—on the rare occasions when she would allow herself such indulgence—would astonish the few friends who heard it.

Meanwhile the portrait prospered, and was at length presented to its subject when she lay recovering from the birth of her second babe—a boy whom they named Arnold—in November, 1876. “Humphry and I are full of delight over the picture,” writes Mary to Mrs. Johnson, “and of wonder at the amount of true and delicate work you have put into it. It will be a possession not only for us but for our children—see how easily the new style comes!” These were prophetic words, for it is indeed the portrait of her that still gives most pleasure to the beholder, though in later years she was painted or drawn by many skilful hands.

Her two babies, Dorothy and Arnold, naturally absorbed a great deal of her time and thoughts in these years, although it was possible in those spacious days to live comfortably and to keep as many little nursery-maids as one required on £800 or £900 a year, which was about the income that husband and wife jointly earned. Her natural talent for “doctoring” showed itself very early in the skill with which she fed her babies or cured them of their ills when they were sick. Nor was she content with her domestic success, but in days before “Infant Welfare” had ever been thought of she wrote a leaflet entitled “Plain Facts on Infant Feeding” and circulated it in the slums of Oxford. We will not, however, rescue it from oblivion, lest it should be found to contain heretical matter! But there was still time for other pursuits, and since both she and her husband did their writing mainly at night, from nine to twelve, Mary began to show her practical powers in other directions, and to take a leading part in the movement for the higher education of women which was then absorbing some of the best minds of Oxford. As early as the winter of 1873-4 a committee was formed among this group of friends, with Mrs. Ward and Mrs. Creighton (followed, on the latter’s departure, by Mrs. T. H. Green) as joint secretaries, for organizing regular “Lectures for Women”—not in any connection with the University, for this was as yet impossible, but in order to satisfy the growing demand among the women residents of Oxford for more serious instruction in history, or modern languages, or Latin. The first series of lectures was held in the early spring of 1874, in the Clarendon Buildings, with Mr. A. H. Johnson as lecturer; it was an immediate success, and the large sum of 5s. which each member of the Committee had put down as a guarantee could be triumphantly refunded. Further courses were arranged in each succeeding winter, till in 1877 the same committee expanded into an “Association for the Education of Women” (again with Mrs. Ward as secretary[9]), which undertook still more important work. The idea of the founding of Women’s Colleges was already in the air, for Girton and Newnham had led the way at Cambridge, and all through 1878 plans were being discussed to this end. In the next year a special committee was formed for the raising of funds towards the foundation of a “Hall of Residence”; Mrs. Ward and Mrs. Augustus Vernon Harcourt were joint secretaries, but since the latter soon fell ill the whole burden of correspondence fell upon Mary’s shoulders. “There seems no end to the things I have to do just now,” she writes to her father in June, 1879. “All the secretary’s work for Somerville Hall falls on me now as my colleague, Mrs. Harcourt, is laid up, and yesterday and the day before I have had the house full of girls being examined for scholarship at the Hall, and have had to copy out examination papers and look after them generally. Our Lady Principal, Miss Shaw-Lefevre, is here and she came to dinner to-night to talk business about furnishing, etc. I think we are getting on. Did you see in The Times that the Clothworkers’ Company have given us 100 guineas?”

And thus the work went on, week after week, all through the year 1879. I have before me a common-looking engagement-diary in which it is all recorded, from the month of March to late in the month of October: all the committee-meetings, all the letters written to newspapers, to prospective students or to possible heads; the decision to purchase the lease of “Walton House,” “to be assigned to the President (Dr. Percival) on August 1”; the builder’s estimate for alterations (“£540 for raising the roof and making twelve bedrooms”), the letters about drainage, or cretonne, or armchairs and fenders, no less than the resolution passed at Balliol on October 24 to “form a Company for the management of the Hall under the Limited Liability Act of 1862, with a nominal capital of £25,000.” But by that time the Hall was already opened and the long labour crowned; and a fortnight afterwards, on November 6, her youngest child was born. It may be hoped that after this Mrs. Ward took a brief holiday from the cares of Somerville.

Mrs. Ward remained a member of the original Council of Somerville Hall long after her departure from Oxford, and during her last two years there continued to be largely responsible, as one of the most active members of the Association for the Education of Women, for the organization of the teaching. All the lectures were arranged by the Association—in consultation, of course, with the Principal—for it was not until 1884 that women students were admitted to the smallest of the University examinations, or to lectures at a few of the Colleges.

Thus had Mrs. Ward learnt her first lesson and won her first laurels in the carrying out of a big piece of public work. It was an experience that was to stand her in good stead in after years. But at this time her ambitions were still largely historical, weaving themselves in dreams and plans for the writing of that big book on the origins of modern Spain of which she afterwards sketched the counterpart in Elsmere’s projected book on the origins of modern France. Very likely she would have settled down to write it before the opening of Somerville, but as early as October, 1877, she had received a very flattering offer from Dean Wace, the general editor of the Dictionary of Christian Biography, to take a large share in writing the lives of the early Spanish ecclesiastics for that monumental work. It was an offer that she could not refuse, and she always spoke with gratitude of the years of hard and exacting work that followed, although once or twice she almost broke down under the strain of it. “Sheer, hard, brain-stretching work,” she calls it in her Recollections, and if anyone will look up her articles on Joannes Biclarensis, or Idatius, or the Histories of Isidore of Seville, they will see how triply justified she was in using the term. “You have gone over the ground so thoroughly that there is no gleaning left,” wrote Mr. C. W. Boase, in those days one of the best-known of Oxford history tutors, while Dean Wace himself, in the many letters he wrote to her, showed by his kindness and consideration how much he valued her contributions. Oxford began to think that she was definitely committed to an historical career, when to its astonishment she came out as the author of a children’s story. “Milly and Olly” was the record of her own “Holiday among the Mountains” with her children in the summer of 1879, but the very simplicity of the tale has endeared it to many generations of children and child-lovers, while the stories it contains of Beowulf and the Spanish Queen give it a note of romance that differentiates it from other nursery tales. She wrote it almost as a relaxation in the summer of 1880; in the midst of her historical work it showed that the story-telling instinct was already stirring within her.