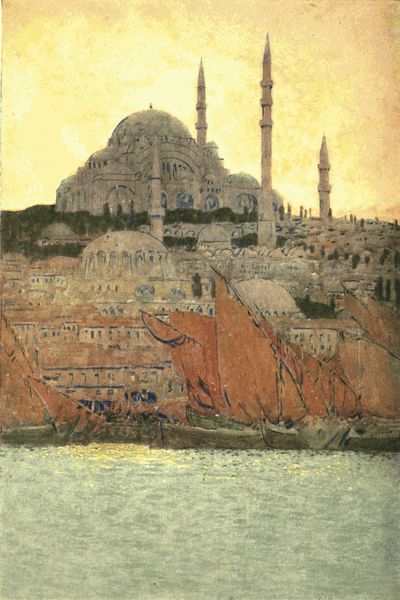

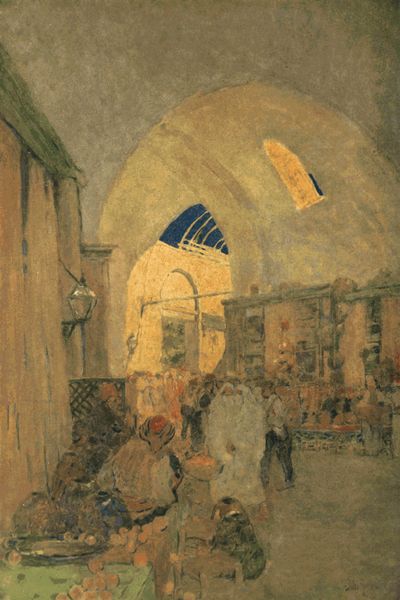

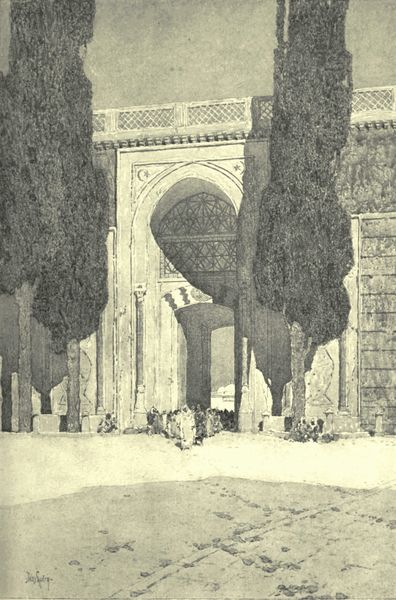

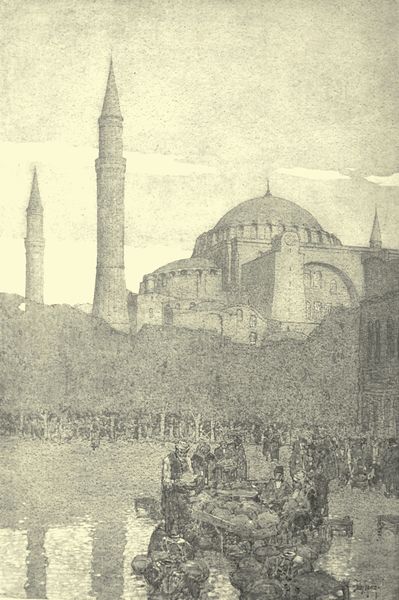

THE MOSQUE OF SULEIMAN AT CONSTANTINOPLE

THE MOSQUE OF SULEIMAN AT CONSTANTINOPLE

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Near East, by Robert Hichens

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Near East

Dalmatia, Greece and Constantinople

Author: Robert Hichens

Illustrator: Jules Guerin

Release Date: March 24, 2012 [EBook #39252]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NEAR EAST ***

Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, JoAnn Greenwood, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE MOSQUE OF SULEIMAN AT CONSTANTINOPLE

THE MOSQUE OF SULEIMAN AT CONSTANTINOPLE

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I | |

| PICTURESQUE DALMATIA | 1 |

| Chapter II | |

| IN AND NEAR ATHENS | 49 |

| Chapter III | |

| THE ENVIRONS OF ATHENS | 95 |

| Chapter IV | |

| DELPHI AND OLYMPIA | 137 |

| Chapter V | |

| IN CONSTANTINOPLE | 181 |

| Chapter VI | |

| STAMBOUL, THE CITY OF MOSQUES | 225 |

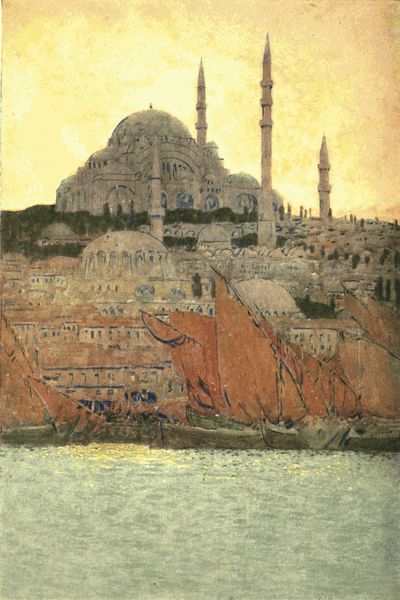

THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATER AT POLA

THE ROMAN AMPHITHEATER AT POLA

Miramar faded across the pale waters of the Adriatic, which lay like a dream at the foot of the hills where Triest seemed sleeping, all its activities stilled at the summons of peace. Beneath its tower the orange-colored sail of a fishing-boat caught the sunlight, and gleamed like some precious fabric, then faded, too, as the ship moved onward to the forgotten region of rocks and islands, of long, gray mountains, of little cities and ancient fortresses, of dim old churches, from whose campanile the medieval voices of bells ring out the angelus to a people still happily primitive, still unashamed to be picturesque. By the way of the sea we journeyed to a capital where no carriages roll through the narrow streets, where there is not a railway-station, where the citizens are content to go on foot about their business, and where three quarters of the blessings of civilization are blessedly unknown. We had still to touch at Pola, in whose great harbor the dull-green war-ships of Austria lay almost in the shadow of the vast Roman amphitheater, which has lifted its white walls, touched here and there with gold, above the sea for some sixteen hundred years, curiously graceful despite its gigantic bulk, the home now of grasses and thistles, where twenty thousand spectators used to assemble to take their pleasure.

But when Pola was left behind, the ship soon entered the watery paradise. Miramar, Triest, were forgotten. Dalmatia is a land of forgetting, seems happily far away, cut off by the sea from many banalities, many active annoyances of modern life.

Places that are, or that seem to be, remote often hold a certain melancholy, a tristesse of "old, unhappy, far-off things." But Dalmatia has a serene atmosphere, a cheerful purity, a clean and a cozy gaiety which reach out hands to the traveler, and take him at once into intimacy and the breast of a home. Before entering it the ship coasts along a naked region, in which pale, almost flesh-colored hills are backed by mountains of a ghastly grayness. Flesh-color and steel are almost cruelly blended. No habitations were visible. The sea, protected on our right by lines of islands, was waveless. No birds flew above it; no boats moved on it. We seemed to be creeping down into the ultimate desolation.

But presently the waters widened out. At the foot of the hills appeared here and there white groups of houses. A greater warmth, like a breath of hope, stole into the air. White and yellow sails showed on the breast of the sea. Two sturdy men, wearing red caps, and standing to ply their oars, hailed us in the Slav dialect as they passed on their way to the islands. The huge, gray Velebit Mountains still bore us company on our voyage to the South, but they were losing their almost wicked look of dreariness. In the golden light of afternoon romance was descending upon them. And now a long spur of green land thrust itself far out, as if to bar our way onward. The islands closed in upon us again. A white town smiled on us far off at the edge of the happy, green land. It looked full of promises, a little city not to be passed without regretting. It was Zara, the capital without a railway-station of the forgotten country.

Zara, Trau, Spalato, Ragusa, Castelnuovo, Cattaro, Sebenico—these, with two or three other places, represent Dalmatia to the average traveler. Ragusa is, perhaps, the most popular and interesting; Spalato the most populous and energetic; Cattaro the most remarkable scenically. Trau leaves a haunting memory in the mind of him who sees it. Castelnuovo is a little paradise marred in some degree by the soldiers who infest it, and who seem strangely out of place in its tiny ways and its tree-shaded piazza on the hilltop. But Zara has a peculiar charm, half gay, half brightly tender. And nowhere else in all Dalmatia are such exquisite effects of light wedded to water to be seen as on Zara's Canale.

Zara, like other sirens, is deceptive. The city has a face which gives little indication of its soul. Along the shore lie tall and cheerful houses,—almost palaces they are,—solid and big, modern, with windows opening to the sea, and separated from it only by a broad walk, edged by a strip of pavement, from which might be taken a dive into the limpid water. And here, when the ship tied up, a well-dressed throng of joyous citizens was taking the air. Children were playing and laughing. Two or three row-boats slipped through the gold and silver which the sun, just setting behind the island of Ugljan opposite, showered toward the city. Music came from some place of entertainment. A simple liveliness suggested prosperous homes, the well-being of a community apart, which chose to live "out of the world," away from railroads, motor-cars, and carriage traffic, but which knew how to be modern in its own quiet and decorous way.

Yet Zara had a great soaring campanile—it had been visible far off at sea—and tiny streets and old buildings, San Donato, the duomo, San Simeone; and five fountains,—the cinque pozzi,—and a Venetian tower,—the Torre di Buovo d'Antona,—and fortification gardens, and lion gateways. Where were all these? A sound of bells came from behind the palaces. And these bells seemed to be proclaiming the truth of Zara.

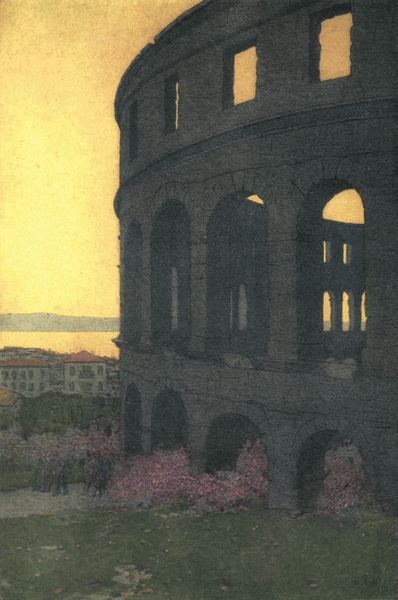

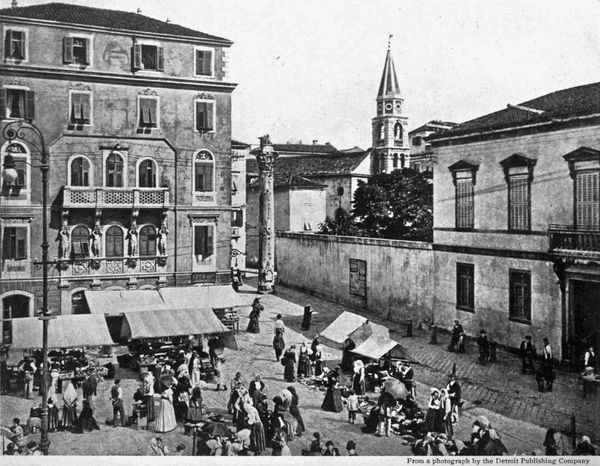

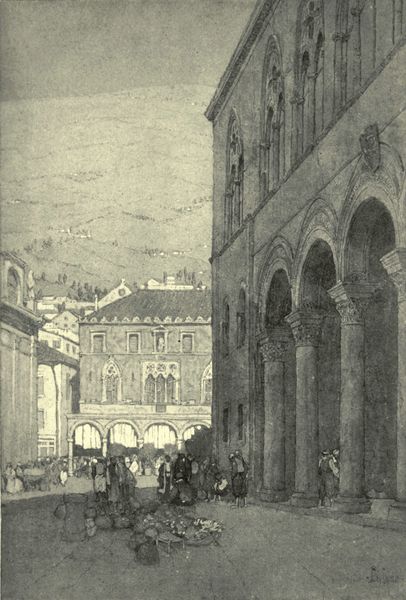

THE MARKET-PLACE AT SPALATO

THE MARKET-PLACE AT SPALATO

Bells ringing in hidden places behind the palaces; bells calling across strange gardens lifted high on mighty walls; bells whispering among pines and murmuring across green depths of glass-like water; bells chiming above the yellowing vines on tiny islands! Who that remembers Zara remembers not Zara's bells?

Walk a few steps from the sea, passing between the big houses which front it into the Piazza delle Erbe, and you come at once into a busy strangeness of Croatia girdled about by Italy. Dalmatia has been possessed wholly or in part by Romans, Goths, Slavs, Hungarians, Turks, Venetians. Now smart Austrian soldiers make themselves at home in Zara, but Italy seems still to rule there, stretching hands out of the past. Italian may be heard on all sides, but the peasants who throng the calle and the market-place and the harbor speak a Slavonic dialect, and in the piazza on any morning, almost in the shadow of the Romanesque cathedral, and watched over by a griffin perched on a high Corinthian column hung with chains, which announce its old service as a pillory, you may hear their chatter, and see the gay colors of costumes which to the untraveled might perhaps suggest comic opera.

There is a wildness of the near East in this medieval Italian town, a wildness which blooms and fades between tall houses of stone, facing each other so closely that friend might almost clasp hand with friend leaning from window to opposite window. Against the somber grays and browns of façades, set in the deep shadows of the paved alleys which are Zara's streets, move brilliant colors, scarlet and silver, blue and crimson and silver. Multitudes of coins and curious heavy ornaments glitter on the caps and the dresses of women. Enormous boys and great, striding men, brave in embroidered jackets, with bright-red caps too small for the head, silver buttons, red sashes stuck full of weapons and other impedimenta, gaiters, and pointed shoes, march hither and thither, calmly intent on some business which has brought them in from the outlying districts. It varies, of course, with the changing seasons. In the latter part of October and beginning of November most of the male peasants were selling very large hares. Live cocks and hens were being disposed of by many of the women, and it is a common thing in Zara to see well-dressed people bearing about with them bunches of puffed-out and drearily blinking poultry, which they have bought casually at some corner; by the great Venetian tower; or near the round, two-storied church of San Donato, founded on the spot where once stood a Roman forum, whose pavement still remains; or perhaps by San Simeone, close to the palace of the governor, where under the black eagles of Austria the sentry, in blue and bright yellow, stands drowsily in the sunshine before his black and yellow box.

ZARA—PIAZZA DELLE ERBE

ZARA—PIAZZA DELLE ERBE

Sometimes the peasants bring live stock to church. One morning, on a week day, I went into San Simeone, to which Queen Elizabeth of Hungary gave the superb arca of silver gilt which contains, it is said, the remains of the saint. I found there a number of peasants, men and women, all in characteristic costumes. Only peasants were there. Some were quietly sitting, some kneeling, some standing, with their market-baskets set down on the pavement beside them. In a hidden place behind the high altar, above which is raised the great, carved sarcophagus, priests were droning the office. A peasant in red, with a gesture, invited me to sit beside him. I did so, and he whispered in my ear some words I could not understand; but I gathered that something very important was about to take place. Every face was expectant. All eyes were earnestly fixed upon the sarcophagus. A woman came in, carrying in her arms a turkey, which looked anxious-minded, crossed herself, and waited with us, gazing. The droning voices ceased. A sort of carillon sounded brightly. We all knelt, the woman with the turkey, too, as a priest in scarlet and white mounted the steps which divide the altar from the area. There was a moment of deep silence. Then the great, glittering, and sloping lid, with its recumbent figure of the saint, slowly rose between the bronze supporting figures. My peasant friend touched me, stood up, and led the way toward the altar. I followed him with the rest of the congregation, and we filed slowly up the steps, and one by one gazed down into the dim coffin. There I saw a skull, and the vague brown remains of what had once been a human being, lying in the midst of votive offerings. On the fingers of one hand, which looked as if made of tobacco leaf, were clusters of rings. The fat, bronze faces on each side seemed smiling. But the peasants stood in awe. And presently the great lid sank down. All made the sign of the cross. The market-baskets were picked up, and the turkey was restored to the sunlight.

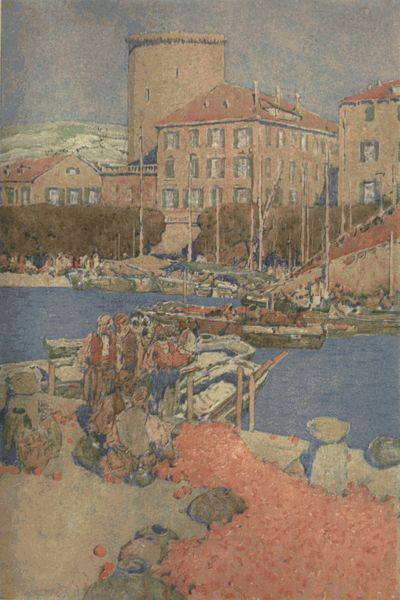

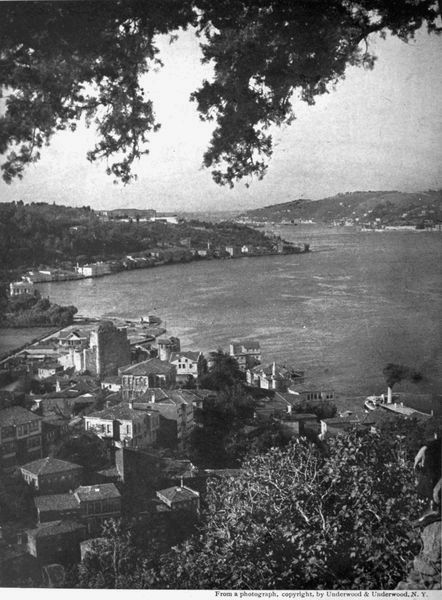

THE HARBOR OF MEZZO

THE HARBOR OF MEZZO

Close to San Simeone are the cinque pozzi—five fountains in a row, with iron wheels above them. They are between four and five hundred years old, and lie almost at the foot of the Venetian tower, near a Corinthian column and the fragments of a Roman arch. Just behind them some steps lead up to one of the delicious shady places of Zara. Mount them, and you will have a happy surprise such as the little Dalmatian cities are always ready to give you.

You have been walking away from the sea, with your back to the harbor, and here is another, but minute, harbor nestling under a great fortress wall above which, in a garden, some young soldiers are idly leaning and laughing under trees with leaves of gold and red-brown. Brightly painted vessels, closely packed together, lie on the blue-green water. Beyond them are the trees of Blažeković Park. And just beneath you, on your right, is the great, yellow stone Porta di Terra Ferma, with its winged lion of St. Mark. Beyond, over the narrow exit from the harbor, the landlocked Canale di Zara, which sometimes, especially at evening, reminded me of the Venice lagoons, lies glittering in the sun. And a Venetian fort on the peak of Ugljan shows like a strange and determined shadow against the blue of the sky.

The great white campanile which dominates Zara, and which from the sea looks light and graceful, is the campanile of the duomo, Sant' Anastasia, and was partly built by the Venetians, and completed not many years ago. From the narrow street which skirts the duomo this campanile, though majestic, looks heavy and almost overwhelming, too huge, too tremendously solid, for the little town in which it is set. And, its blanched hue, beautiful from the sea, has a rather unpleasant effect against the deep, time-worn color of the church, the façade of which, with its two rose windows, one large, one small, its three beautiful, mellow-toned doorways, and its curious and somehow touching, though stolid, statues, is very fine. The interior, not specially interesting, contains some glorious Gothic stalls dating from the fifteenth century. They are of black wood, relieved with bosses and tiny statuettes of bright gold, and above each one is the half-length of a gilded and painted man, wearing a beard and holding a scroll. The Porta Marina, through which the chief harbor is gained, is remarkable for its carved, dark-gray lion, companioned by two white cherubs of stone brilliantly full of life despite their almost terrifying obesity. One of the most beautiful things in Zara is the delicate and lovely campanile of Santa Maria, over six hundred years old. St. Grisogono, the church of the city's patron saint, was in the hands of workmen and could not be visited when I was in Dalmatia.

Almost the whole of Zara is surrounded by water. On the great walls of the ancient fortifications are gardens, and from these gardens you look down on quiet inlets of the sea. Old buildings, old walls and gardens, tiny, medieval streets through which no carriage ever passes, fountains, lion gateways, painted boats lying on clear and apparently motionless waters shut in from the open sea by long lines of mountainous islands, pine-trees and olives and golden vineyards, and over all an ancient music of bells. It is difficult to say good-by to Zara, even though Spalato sends out a summons from the riviera of red and of gold, even though Ragusa calls from its leafy groves under the Fort Imperiale.

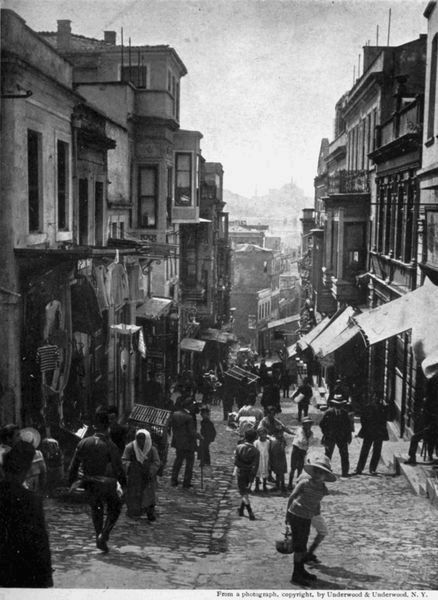

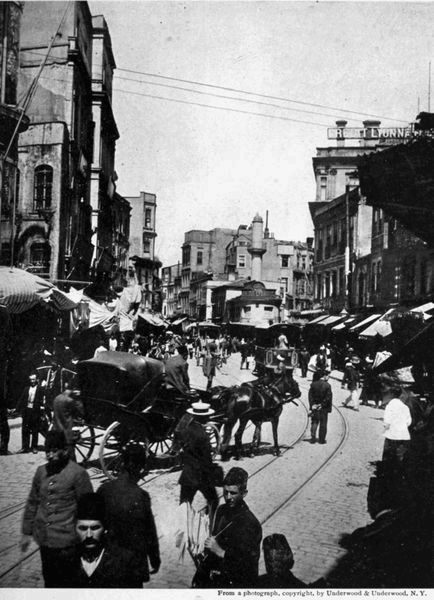

Bora, the wind of the dead, blew when our ship rounded the lighthouse of Spalato long after darkness had fallen. And the following day was the "giorno dei morti." The strange cathedral, octagonal without, circular within, once the mausoleum of the Emperor Diocletian, was crowded with citizens and peasants devoutly praying. Incense rose between the dark, hoary walls, the columns of granite and porphyry, to the dome of brick. Outside in the wind the black hornblende sphinx kept watch on those who came and went, mourning for their departed. The sky was a heavy gray, and the temple was dark, and looked wrinkled and seared with age, and sad despite its pagan frieze showing the wild joys of the chase, despite the loveliness of its thirteenth-century pulpit of limestone and marble, raised high on wonderfully graceful columns with elaborately carved capitals.

Spalato is the biggest, most bustling town of Dalmatia. Much of it is built into the great palace of Diocletian, which lies over against the sea, huge, massive, powerful, once probably noble, but now disfigured by the paltry windows and the green shutters of modern dwellings, by a triviality of common commercial life, sparrows where eagles should be. When nature takes a ruin, she usually glorifies it, or touches it with a tenderness of romance. But when people in the wine trade lay hold upon it, hang out their washing in it, and establish their cafés and their bakeries and their butchers' shops in the midst of its rugged walls, its arches, and its columns, the ruin suffers, and the people in the wine trade seem to lose in value instead of gaining in importance.

SPALATO—PERISTILIO

SPALATO—PERISTILIO

Spalato is a strange confusion of old and new. It lacks the delicacy of Zara, the harmonious beauty of Ragusa. One era seems to fight with another within it. Here is a noble twelfth-century campanile, nearly a hundred and eighty feet high, there a common row of little shops full of cheap and uninviting articles. Turning a corner, one comes unexpectedly upon a Corinthian temple. It is the Battistero di San Giovanni, once perhaps the private temple of Diocletian. For the moment no one is near it, and despite the icy breath of Bora raging through the city and crying, "This is the day of the dead!" a calm of dead years infolds you as you enter the massive doorway and pass into the shadow beneath the stone wagon-roof. A few steps, and the smell of fish assails you, hundreds of strings of onions greet your eyes, and the heavy rolling of enormous barrels of wine over stone pavements breaks through the noise of the wind. You have come unexpectedly out through a gateway of the palace on to the quay to the south, and are in the midst of commercial activities. The contrasts are picturesque, but they are rough, and, when complicated by Bora, are confusing, almost distressing. Nevertheless, Spalato is well worth a visit. It contains a small, but remarkable, museum, specially interesting for its sarcophagi found at Salona and its collection of inscriptions. The sarcophagus showing the passage of the Red Sea is very curious. Apart from the now disfigured palace, the Battistero, the very interesting and peculiar cathedral, with its vestibule, its rotunda, and its Piazza of the Sphinx, like nothing else I have seen, the town is full of picturesque nooks and corners; and its fruit market at the foot of the massive octagonal Hrvoja Tower, which dates from 1481, is perhaps even more animated, more full of strangeness and color, than Zara's Piazza delle Erbe. Here may be seen turbans of crimson on the handsome heads of men, elaborately embroidered crimson jackets covering immense shoulders and chests, women dressed in blue and red, white and silver, or with heads and busts draped in the most brilliant shade of orange color. When Bora blows, the men look like monks or Mephistopheles; for some—the greater number—wrap themselves from head to foot in long cloaks and hoods of brown, while others of a more lively temperament shroud themselves in red. They are a handsome people, rustic-looking, yet often noble, with kind yet bold faces, steady eyes, and a magnificent physique. Their gait is large and loose. There are giants in Dalmatia in our days. And many of the women are not only pretty, but have delightful expressions, open, pure, and gay. There seems to be nothing to fear in Dalmatia. I have driven through the wilds, and over the flanks of the mountains, both in Dalmatia and Herzegovina, in the dead of the night, and had no unpleasant experience. The peasants have a high reputation for honesty and general probity as well as for courage. And beggars are scarce, if they exist at all, in Dalmatia.

Trau has a unique charm. The riviera of the Sette Castelli stretches between it and Spalato, along the shore of an inlet of the sea which is exactly like a blue lake. And what a marvelous blue it is on a cloudless autumn day! Every one knows what is meant by a rapture of spring. Those who traverse that riviera at the end of October, or even in the opening days of November, will know what a rapture of autumn can be.

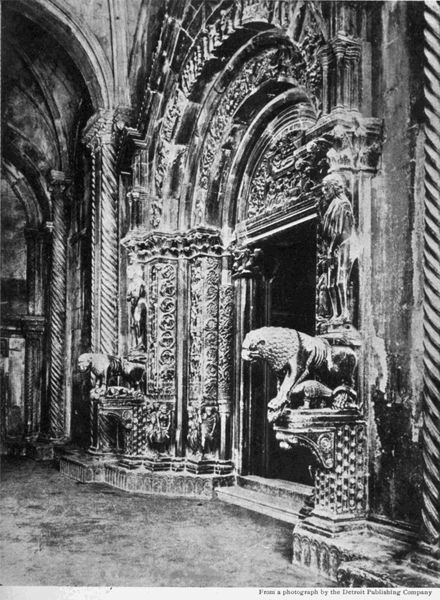

TRAU—VESTIBULE OF THE CATHEDRAL

TRAU—VESTIBULE OF THE CATHEDRAL

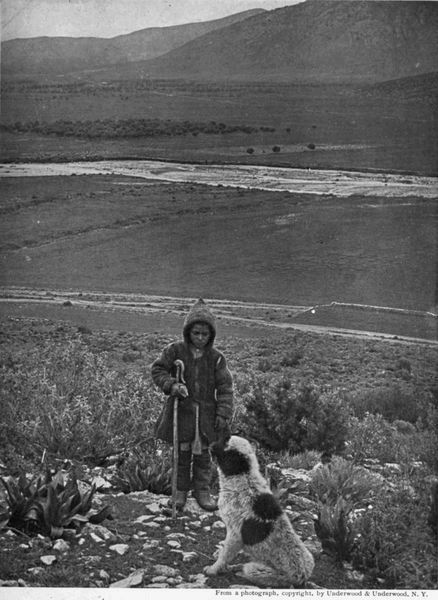

Miles upon miles of bright-golden and rose-red vineyards edge the startling blue of the sea. And the vines are not stunted and ugly, but large, leafy, growing with a rank luxuriance. Among them, with trunks caught as it were in the warm embraces of these troops of bacchantes, are thousands of silver-green olive-trees. And peasants in red, peasants in orange-color, move waist-deep, sometimes shoulder-deep, through the glory, under the glory of the sun. Here and there in a grass-grown clearing, like a small islet in the ocean of vines, appears a hut of brushwood and woven grasses, and under the trees before it sit peasants eating the grapes they have just picked warm from the plants. Now and then a sportsman may be seen, in peasant costume, smoking a cigarette, his gun over his shoulder, passing slowly with his red-brown dog among the red-gold vines. Now and then a distant report rings out among the olives. Then the warm silence falls again over this rapture of autumn. And so, you come to Trau.

Trau is a tiny town set on a tiny island approached by bridges, medieval, sleepy, yet happy, almost drowsily joyous, in appearance, with that air of half-gentle, half-blithe satisfaction with self which makes so many Dalmatian places characteristic and almost touching. How odd to live in Trau! Yet might it not be a delicious experience to live in dear little Trau with the right person, separated from the world by the shining water,—for who comes over the bridges, when all is said?—guarded by the lion and the statue which crown the gateway, cradled in peace and mellow fruitfulness?

The gateway passed, a narrow alley or two threaded, a corner turned, and, lo! a piazza, a loggia with fine old columns, a tiled roof and a clock-tower, a campanile and a cathedral with a great porch, and underneath the porch a marvel of a doorway! Can tiny Trau on its tiny island really possess all this?

The lion doorway of the duomo at Trau is certainly one of the finest things in Dalmatia. The duomo dates from the thirteenth century, but has been twice enlarged. It is not large now, but small and high, dim, full of the smell of stale incense, blackened by age, almost strangely silent, almost strangely secluded. In the choir is a deep well with an old well-head. There are many tombs in the pavement. The finely carved pulpit, with its little lion, and the fifteenth-century choir-stalls are well worth seeing, and the roof of the chapel of St. Giovanni Orsini, which contains a great marble tomb, has been made wonderful by age, like an old face made wonderful by wrinkles. But Radovan's doorway is certainly the marvel of Trau. In color it is a rich, deep, dusty brown, and it is elaborately and splendidly carved with two big lions, with Adam on a lion and with Eve on a lioness. The lioness is grasping a lamb. There is a multiplicity of other detail. The two big lions, which stick out on each side of the round-arched doorway, as if about to step forth into the alleys of Trau, have a fine air of life, though they both look tame. Their mouths are open, but almost smiling.

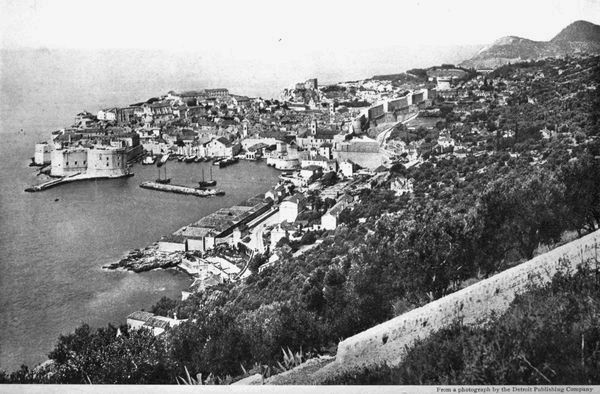

RAGUSA

RAGUSA

When you leave the duomo, wander through the Venetian streets of this wonderful little island city, where Gothic windows and beautifully carved balconies look out to, lean forth to, the calm, blue waters, edged by the red and the gold of the vines. For this place is unique and has an unique charm. Peace dwells here, and beauty has found a quiet abiding-place, where it lingers, and will linger, I hope, for many centuries yet, girdled by olive-groves, by vineyards, by sun-kissed waters, guarded by the lions of Venice.

From Spalato I visited the white ruins of Salona, where the Emperor Diocletian was born, and near which, in his palace at Spalato, he spent the last eight years of his life, cultivating his garden, seeking after philosophy, and, let us hope, repenting of his bitter persecution of the Christians. From the hill, on the site of the Basilica Urbana, I saw one of those frigid and almost terrible lemon sunsets which come with the wind of the dead. I stayed till night despite the intense cold, till the fragments of the city, scattered far over the sloping ground above the riviera of the Sette Castelli, and creeping up to the solitary dwelling-house built by Professor Bulic of old Roman stones, took on sad and unnatural pallors in the darkness, till lonely columns stood up like watching specters, and fragments of wall were like specters crouching. For a long while the lemon hue persisted in the western sky, and the voice of the wind rose with the night, crying among the burial-places.

A few hours' voyage on a splendid ship, and you step ashore at Gravosa, the port for Ragusa, the most popular place in Dalmatia, and in many ways the most attractive. For it is embowered in woods and gardens; contains remarkable old buildings; is girdled about by tremendous fortress walls, and by forts perched on bastions of rock overlooking the sea and the isle of Lacroma, where Richard Cœur de Lion touched land and founded a monastery; is thoroughly and deliciously medieval, yet full of Slav and Austrian life; possesses a railway-station, many well-built villas, and a good hotel, and is surrounded by delightful country. Perhaps in all Dalmatia Ragusa is the best center from which to take long walks and make expeditions. It is cheery, cozy, and wonderful at the same time. The terrific walls of the fortresses do not appal or overwhelm, for all about them cluster the gardens. Ivy climbs over the archways. In what was once a moat the grass grows thickly, the flowers bloom, and many trees give shade. This is a medieval paradise, and its inhabitants have reason to rejoice in it and to say there is no place like it.

Though small, it is intricate. At every moment one is surprised by some unexpected view, by some marvel of masonry, militant or ecclesiastical; by a fountain or a statue, an old doorway, a courtyard, a campanile, an exquisite façade, with arches and lovely columns, balconies and carved window-frames; by cloisters, a strange alley ending in flights of steps, which lead to a mountain from which a fort looks down; by a secret harbor, or a secret garden, or a little magical grove nestling beneath a protecting wall which dates from the Middle Ages, when Ragusa was a proud republic.

Was Burne-Jones ever in Ragusa? It is like one of the little enchanted towns he loved to paint in the backgrounds of his pictures. Was William Morris ever there? It is like a city in one of his poems. It is full of churches, and their towers are full of bells. Monks and priests pass perpetually through the narrow streets with smartly dressed Austrian soldiers. And military music, the triumph of bugles and trumpets, the beat and rattle of drums, joins with the drowsy sound of church organs, and the old voices of clocks chiming the hours, to make the symphony of Ragusa. Men and women from the Breno Valley, from Canali the golden, where oaks grow among the rocks, and the autumn vineyards are a wonder forever to haunt the memory, from Melada and the Stag Islands, from the Ombla and Herzegovina, pass all day down "the Stradone," stroll in the Brsalje, a piazza with mulberry-trees overlooking the sea, talk by the Amerling fountain, or sit on the wall by Porta Pille under the statue of San Biagio, the patron saint of the town. And each one is in a picturesque, perhaps even a brilliant, costume. The men often wear long chains, and carry handsomely chased weapons and long, elaborate pipes. Some have sheepskins flung jauntily over their shoulders, and bright-red caps. The women wear golden ornaments, embroidered jackets, and marvelous aprons almost like prayer-rugs, handsome pins, pleated head-dresses, bright-colored handkerchiefs or tiny caps, coins hanging on chains over their thickly growing hair.

The chief hotels, the villas, and the railway-station, where a row of victorias is drawn up,—for this is no Zara, but a city which believes that it "moves with the times,"—lie among roses, oleanders, single rhododendrons, trees, and masses of luxuriant vegetation outside Porta Pille. As soon as you have passed beneath San Biagio and descended the hill, you are in a bright, medieval world, in the heart of one of the most original and fascinating little cities that exists in Europe.

THE RECTOR'S PALACE AND THE PUBLIC SQUARE AT RAGUSA

THE RECTOR'S PALACE AND THE PUBLIC SQUARE AT RAGUSA

On the left of the Stradone, the chief street and the newest, between two and three hundred years old, at right angles to it, shadowed by tall and ancient houses, tiny alleys, ending in steep flights of steps, lead up toward the mountain. On the flat to its right is a happy maze of alleys, clean, strange, old, yet never sad. A delicious cheerfulness reigns in Ragusa. From the dimness of venerable doorways smiling faces look forth. They lean down from carved stone balconies. Gay voices chatter at the foot of frowning walls, huge bastions, mighty watch-towers; before the statue of Roland, near the Dogana which has a loggia and Gothic windows; by the fine and massive Onofrio fountain, which for over four hundred and seventy years has given water to the inhabitants; among the doves by Porta Place, which leads to the harbor. The wide, but intimate, Stradone toward noon and evening is thronged with cheerful and neatly dressed citizens, strolling to and fro in the soft air between the delicious little shops full of fine rugs, weapons, chains, and filigree ornaments.

Opposite the fountain of Onofrio are the church, monastery, and cloisters of the Franciscans, with a courtyard and an old pharmacy containing some wonderful vases. At the east end of the Stradone, away to the right, are the church of San Biagio, the cathedral, and the Palazzo dei Rettori. On the other side of the street are the military hospital and the church of the Jesuits. Not far away is the Dominican monastery.

Of these the most remarkable is the rector's palace. But the cloisters of the Franciscans are beautiful and hold an extraordinary charm and peace. The rector's palace is a noble Renaissance building, with a courtyard containing a very handsome staircase, and with a really splendid fifteenth-century colonnade fronting the piazza. The carving of the capitals of the columns is wonderfully effective. Three are said to be inferior to the remaining four, which were the work of an architect of Naples, Onofrio. But all are remarkable. The little winged boys have a tenderness and liveliness, a softness and activity, which are quite exquisite. The windows of Venetian Gothic are beautiful; and the whole effect of this façade, with its carved doorway, the round arches, richly dark, with notes of white, the two tiers of stone seats raised one above the other, and the double rows of windows, square and arched, in the shadow of the colonnade, is absolutely noble.

The cathedral is not very interesting, and the "Assumption" over the high altar, though attributed to Titian, cannot be by him. Much more attractive is a copy of the Madonna della Sedia of Raphael. The treasury contains some remarkable jewels and silver and many relics.

In the Dominican church there is a genuine Titian, and there are some very curious and interesting pictures by Nicolo Ragusano, a painter of Ragusa who lived in the fifteenth century. The cloisters contain a white well-head, guarded by graceful columns, orange-trees, and flowers, above which peer the small windows of the monks. But if one had to be a monk in Ragusa, surely it would be wise to cast in your lot with the Franciscans at the other end of the street, whose Romanesque fourteenth-century cloisters with octagonal columns are quite beautiful and in excellent preservation. The capitals of the columns are carved with animals. Palms flourish there, and roses. Above, a terrace, with a wonderful balustrade—a series of tiny arches resting on tiny columns, a sort of stone echo of the arches and columns below,—runs all round the court. The peace is profound, but not sad. As one lingers there one can understand, indeed one can scarcely help understanding, the very peculiar charm which must often attach to the monkish life.

Ragusa contains some nine thousand inhabitants. One of them remarked that eight hundred of these were ecclesiastics. And he was unsympathetic enough to add, "E molto troppo!" Perhaps his statement was untrue. But certainly the ways of Ragusa swarm with religious. Nevertheless,—one thinks of Rome, with its crowds of priests and its crowds of free-thinkers,—the inhabitants of Ragusa seem to be very devout. In almost all of the many churches, at all times of the day, people may be found praying, meditating, telling their beads, worshiping at shrines of the saints.

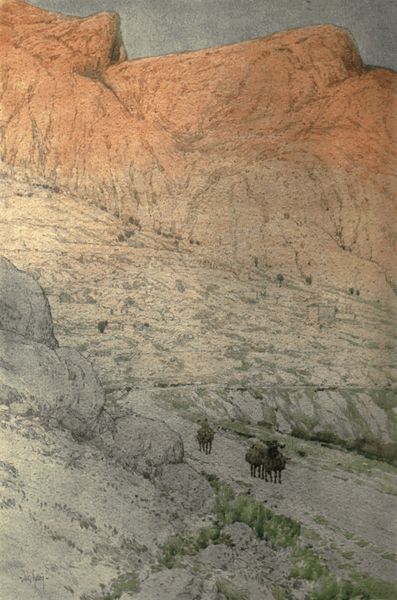

Around Ragusa there are many beautiful walks, on Lacroma, on Lapad by Gravosa, on Monte Sergio, on Monte Petka. A really superb drive is the expedition to Castelnuovo in the Bocche di Cattaro, along the Dalmatian riviera, which is as fine as almost any part of the French riviera, and which is still wild and natural, not yet turned into a vanity-box. Those who take this glorious drive will cross the frontier into Herzegovina, and, best of all, they will pass by the wonderful vineyards of Canali, which roll in waves of gold to the very feet of a chain of naked and savage mountains.

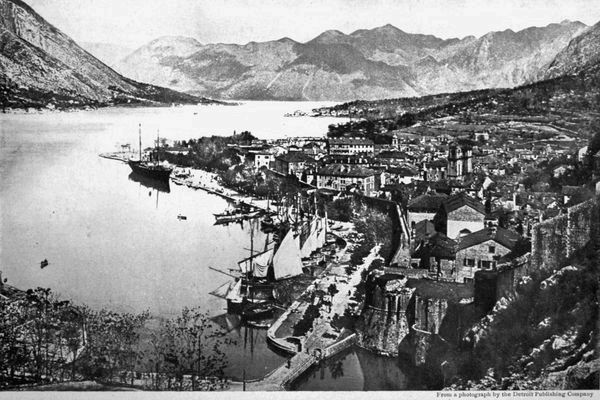

The voyage from Ragusa to Cattaro is one of the finest in Europe. The entrance into the bocche, the journey through them, and the arrival at Cattaro, hidden away like some precious thing that must not be revealed to the dull gaze of the ordinary world, almost, but mercifully not quite, under the giant shadow of the Black Mountain, make for the voyager what comes to seem at length a deliberately planned, and triumphantly carried out, scenic crescendo, which closes in sheer magic.

The coast of Dalmatia is guarded by chains of islands and is pierced by many long and narrow inlets. During the voyage from Triest or Fiume to the extreme south of the country, the ship, often for many hours, seems to be traveling over a series of lakes. Rarely does she emerge into open water. But between Gravosa and the bocche there is open sea. Nature has not neglected to make her preparations. She gives you the stretch of open sea as a contrast to what is coming. And just when you are beginning to feel its monotony, the prow of the vessel veers to the left, seems to be sensitively searching for some unseen opening in the rugged coast. She finds that opening between Punta d'Ostro and Punta d'Arza, leaving the little isle of Rondoni, with its round, yellow fort, on the right and the open sea behind.

The mountains which guard the bocche are nearly six thousand feet high, bare, cruelly precipitous, in color a peculiar, almost ashy, gray. When you are at a long distance from them they seem to descend sheer into the water; but as you draw nearer over the waveless sea, you find that along their bases runs a strip of beautiful fertile country, green, thickly wooded in many places, with gay little villages set among radiant gardens, with a white highroad, along which peasants are passing. There is Castelnuovo on its hill among leafy groves, with its old, narrow fortress on the rock fought for by Turks and Venetians; near by is Zelenika; and there another large fortress, with the Austrian flag above it. The sensitive prow of the ship veers again, this time to the southeast, where the ash-gray precipices surely hold the sea forever in check. But the ship knows better. The Canale di Kumbur shows itself, leading to the splendid Bay of Teodo surreptitiously observed from afar by the mountains of Montenegro. If you held your breath and listened, might you not hear the boom of guns by the lake of Scutari? All sense of being at sea fades from you as the ship penetrates ever more deeply into the secret recesses of the mountains. This is like superb lake scenery, austere, grand, almost terrible, and yet radiant. Nature is even coquettish on this perfect morning of autumn, for in these remoter regions she has cast a swathe of the lightest and whitest possible mist, like one of those scarfs of Tunis, over the cultivated land which edges the precipices. As the ship draws near, the mist seems to disperse in a sparkle of gold, revealing intimate beauties, full of charming detail: a little Byzantine church with a pale-green cupola, a priest in a sunny garden leaning over a creeper-covered wall, white horses trotting briskly along a curly, white road, soldiers marching through a village with a faint beat of drums, children perhaps going to school through a riot of green. But the mist is ever there in the distance, part of the spirit of autumn.

THE JESUITS' CHURCH AND THE MILITARY HOSPITAL, RAGUSA

THE JESUITS' CHURCH AND THE MILITARY HOSPITAL, RAGUSA

Do not miss the tiny twin islands with their two little churches. One of them, Santa Maria dello Scalpello, is a place of pilgrimage. Old, gray, minute yet dignified, with its few tall cypresses about it, it so completely covers the island that you see only a church with cypresses apparently floating upon the water. Now there is a scatter of ivory-white birds on the steel-colored surface, a glint of powder-blue on the ridges made by the ship. Marvelous harmonies of pearl color, gray, and blue, with here and there faint dashes of primrose-yellow, make magic in the distance before you. This is really an enchanted place, home of a peace that seems touched with eternity. And the ship creeps on, as if fearing perhaps to disturb it, farther and farther into places more secret still, and of a peace even more profound, till the pearl color and the gray, with their hints of yellow and blue, begin to give way to another dominion. The last bay has been gained. The secret of Cattaro is to be at length revealed. Through the wondrous delicacies of the now rather suggested than actually seen mist, and above them, dawns a marvelous pageant of autumn, which bears a curiously exact resemblance to one of Turner's superb visions.

It is like a dream, but a dream of ardor and power, in which browns, reds, russets, greens, and many shades of gold and of yellow march together from the circle of the waters through climbing valleys to the mountains, which here at last give pause to the sea. And bells are ringing in this great, this triumphant dream. And now surely faint outlines are becoming visible, as of turrets and cupolas striving to break in glory through the mist. The fires of autumn glow more fiercely, like a furnace fanned. Trails of smoke show here and there. Mist, smoke, and fire—it is like a grand conflagration. The turrets reveal themselves as great groups of trees. But the smoke rises from household fires; the cupolas are cupolas of churches; and the bells are the bells of Cattaro, calling from this vale of enchantment to the cannon which are thundering before Scutari beyond the mountains of Montenegro.

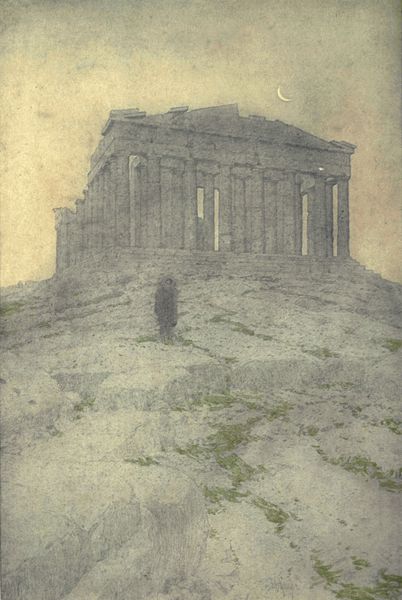

THE PARTHENON AT ATHENS

THE PARTHENON AT ATHENS

What Greece is like in spring, I do not know, when rains have fallen, and round Athens the country is green, when the white dust perhaps does not whirl through Constitution Square and over the garden about the Zappeion, when the intensity of the sun is not fierce on the road to the bare Acropolis, and the guardians of the Parthenon, in their long coats the color of a dervish's hat, do not fall asleep in the patches of shade cast on the hot ground by Doric columns. I was there at the end of the summer, and many said to me, "You should come in spring, when it is green."

Greece must be very different then, but can it be much more beautiful?

Disembark at the Piræus at dawn, take a carriage, and drive by Phalerum, the bathing-place of the Athenians, to Athens at the end of the summer, and though for just six months no rain has fallen, you will enter a bath of dew. The road is dry and dusty, but there is no wind, and the dust lies still. The atmosphere is marvelously clear, as it is, say, at Ismailia in the early morning. The Hellenes, when they are talking quite naturally, if they speak of Europe, always speak of it as a continent in which Greece is not included. They talk of "going to Europe." They say to the English stranger, "You come to us fresh from Europe." And as you drive toward Athens you understand.

This country is part of the East, although the Greeks were the people who saved Europe from being dominated by the races of Asia. All about you—you have not yet reached Phalerum—you see country that looks like the beginning of a desert, that holds a fascination of the desert. The few trees stand up like carved things. The small, Eastern-looking houses, many of them with flat roofs, earth-colored, white, or tinted with mauve and pale colors, scattered casually and apparently without any plan over the absolutely bare and tawny ground, look from a distance as if they, too, were carved, as if they were actually a part of the substance of their environment, not imposed upon it by an outside force. The moving figure of a man, wearing the white fustanella, has the strange beauty of an Arab moving alone in the vast sands. And yet there is something here that is certainly not of Europe, but that is not wholly of the East—something very delicate, very pure, very sensitive, very individual, free from the Eastern drowsiness, from the heavy Eastern perfume which disposes the soul of man to inertia.

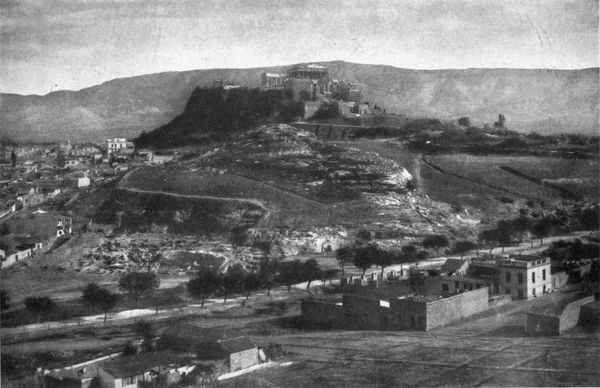

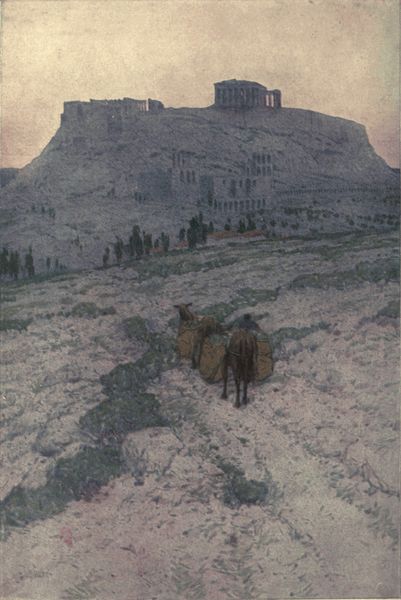

THE ACROPOLIS, WITH A VIEW OF THE AREOPAGUS AND MOUNT

HYMETTUS, FROM THE WEST

THE ACROPOLIS, WITH A VIEW OF THE AREOPAGUS AND MOUNT

HYMETTUS, FROM THE WEST

It is the exquisite, vital, one might almost say intellectual, freshness of Greece which, between Europe and Asia, preserves its eternal dewdrops—those dewdrops which still make it the land of the early morning.

Your carriage turns to the right, and in a moment you are driving along the shore of a sea without wave or even ripple. In the distance, across the purple water, is the calm mountain of the island of Ægina. Over there, along the curve of the sandy bay, are the clustering houses of old Phalerum. This is new Phalerum, with its wooden bath-houses, its one great hotel, its kiosks and cafés, its shadeless plage, deserted now except for one old gentleman who, like almost every Greek all over the country, is at this moment reading a newspaper in the sun.

Is there any special charm in new Phalerum, bare of trees, a little cockney of aspect, any exceptional beauty in this bay? When you have bathed there a few times, when you have walked along the shore in the quiet evening, breathing the exquisite air, when you have dined in a café of old Phalerum built out into the sea, and come back by boat through the silver of a moon to the little tram station whence you return to Athens, you will probably find that there is. And from what other bay can you see the temple of the Parthenon as you see it from the bay of Phalerum?

You have your first vision of it now, as you look away from the sea, lifted very high on its great rock of the Acropolis as on a throne. Though far off, nevertheless its majesty is essentially the same, casts the same tremendous influence upon you here as it does when you stand at the very feet of its mighty columns. At once you know, not because of the legend of greatness attaching to it, or because of the historical associations clinging about it, but simply because of the feeling in your own soul roused by its white silhouette in this morning hour, that the soul of Greece—eternal majesty, supreme greatness, divine calm, and that remoteness from which, perhaps, no perfect thing, either God-made or, because of God's breath in him, man-made, is wholly exempt—is lifted high before you under the cloudless heaven of dawn.

You may even realize at once and forever, as you send on your carriage and stand for a while quite alone on the sands, gazing, that to you the soul of Greece must always seem to be Doric. From afar the Doric conquers.

The ancient Hellenes, divided, at enmity, incessantly warring among themselves, were united in one sentiment: they called all the rest of the nations "barbarians." The Parthenon gives them reason. "Unintelligible folk" to this day must acknowledge it, using the word "barbarian" strictly in our modern sense.

But the sun is higher, the morning draws on; you must be gone to Athens. Down the long, straight, new road, between rows of pepper-trees, passing a little church which marks the spot where a miscreant tried to assassinate King George, and always through beautiful, bare country like the desert, you drive. And presently you see a few houses, like the houses of a quiet village; a few great Corinthian columns rising up in a lonely place beyond an arch tawny with old gold; a public garden looking new but pleasant,—not unlike a desert garden at the edge of the Suez Canal,—with a white statue (it is the statue of Byron) before it; then a long, thick tangle of trees stretching far, and separated from the road and a line of large apartment-houses only by an old and slight wooden paling; a big square with a garden sunken below the level you are on, and on your right a huge, bare white building rather like a barracks. You are in Athens, and you have seen already the Olympieion, the Arch of Hadrian, the Zappeion garden, Constitution Square, and the garden and the palace of the king.

Coming to Athens for the first time by this route, it is difficult to believe one is in the famous capital, even though one has seen the Acropolis. And I never quite lost the feeling there that I was in a delightful village, containing a cheery, bustling life, some fine modern buildings, and many wonders of the past. Yet Athens is large and is continually growing. One of the best and most complete views of it is obtained from the terrace near the Acropolis Museum, behind the Parthenon. Other fine views can be had from Lycabettus, the solitary and fierce-looking hill against whose rocks the town seems almost to surge, like a wave striving to overwhelm it, and from that other hill, immediately facing the Acropolis, on which stands the monument of Philopappos.

It is easy to ascend to the summit of the Acropolis, even in the fierce heat of a summer day. A stroll up a curving road, the mounting of some steps, and you are there, five hundred and ten feet only above the level of the sea. But on account of the solitary situation of the plateau of rock on which the temples are grouped and of its precipitous sides, it seems very much higher than it is. Whenever I stood on the summit of the Acropolis I felt as if I were on the peak of a mountain, as if from there one must be able to see all the kingdoms of the world and the glory of them.

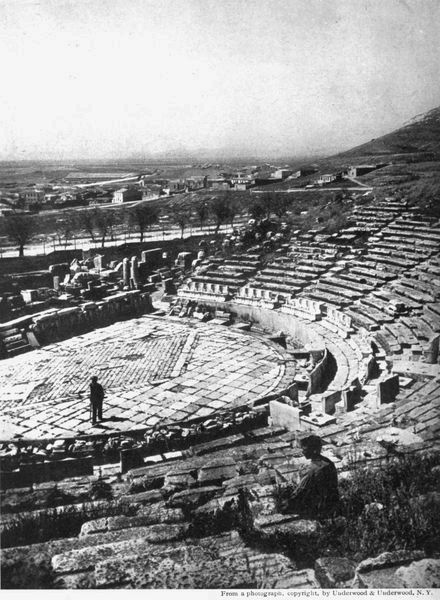

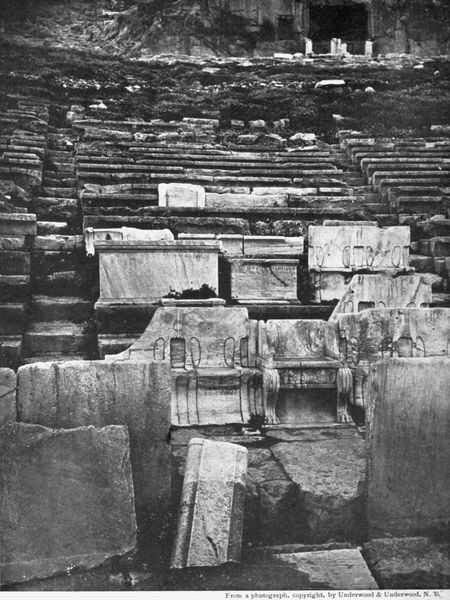

THE THEATER OF DIONYSUS ON THE SOUTHERN SLOPE OF THE

ACROPOLIS

THE THEATER OF DIONYSUS ON THE SOUTHERN SLOPE OF THE

ACROPOLIS

What one does see is marvelously, almost ineffably beautiful. Herodotus called this land, with its stony soil and its multitudes of bare mountains, the "rugged nurse of liberty." Though rugged, and often naked, nevertheless its loveliness—and that soft word must be used—is so great and so pure that, as we give to Greek art the crown of wild olive, so we must give it surely also to the scenery of Greece. It is a loveliness of outline, of color, and above all of light.

Almost everywhere in Greece you see mountains, range upon range, closing about you or, more often, melting away into far distances, into outlines of shadows and dreams. Almost everywhere, or so it seemed to me, you look upon the sea. And as the outlines of the mountains of Greece are nearly always divinely calm, so the colors of the seas of Greece are magically deep and radiant and varied. And over mountains and seas fall changing wonders of light, giving to outline eternal meanings, to color the depth of a soul.

When you stand upon the Acropolis you see not only ruins which, taking everything into consideration, are perhaps the most wonderful in the world, but also one of the most beautiful views of the world. It is asserted as a fact by authorities that the ancient Greeks had little or no feeling for beauty of landscape. One famous writer on things Greek states that "a fine view as such had little attraction for them," that is, the Greeks. It is very difficult for those who are familiar with the sites the Greeks selected for their great temples and theaters, such as the rock of the Acropolis, the heights at Sunium and at Argos, the hill at Taormina in Sicily, etc., to feel assured of this, however lacking in allusion to the beauty of nature, unless in connection with supposed animating intelligences, Greek literature may be. It is almost impossible to believe it as you stand on the Acropolis.

All Athens lies beneath you, pale, almost white, with hints of mauve and yellow, gray and brown, with its dominating palace, its tiny Byzantine churches, its tiled and flat roofs, its solitary cypress-trees and gardens. Lycabettus stands out, small, but bold, almost defiant. Beyond, and on every side, stretches the calm plain of Attica. That winding river of dust marks the Via Sacra, along which the great processions used to pass to Eleusis by the water. There are the dark groves of Academe, a place of rest in a bare land. The marble quarries gleam white on the long flanks of Mount Pentelicus, and the great range of Parnes leads on to Ægaleos. Near you are the Hill of the Nymphs, with its observatory; the rocky plateau from which the apostle Paul spoke of Christ to the doubting Athenians; the new plantation at the foot of Philopappos which surrounds the so-called "Prison of Socrates." Honey-famed Hymettus, gray and patient, stretches toward the sea—toward the shining Saronic Gulf and the bay of Phalerum. And there, beyond Phalerum, are the Piræus and Salamis. Mount Elias rules over the midmost isle of Ægina. Beneath the height of Sunium, where the Temple of Poseidon still lifts blanched columns above the passing mariners who have no care for the sea-god's glory, lies the islet of Gaidaronisi, and the mountains of Megara and of Argolis lie like dreaming shadows in the sunlight. Very pure, very perfect, is this great view. Nature here seems purged of all excesses, and even nature in certain places can look almost theatrical, though never in Greece. The sea shines with gold, is decked with marvelous purple, glimmers afar with silver, fades into the color of shadow. The shapes of the mountains are as serene as the shapes of Greek statues. Though bare, these mountains are not savage, are not desolate or sad. Nor is there here any suggestion of that "oppressive beauty" against which the American painter-poet Frederic Crowninshield cries out in a recent poem—of that beauty which weighs upon, rather than releases, the heart of man.

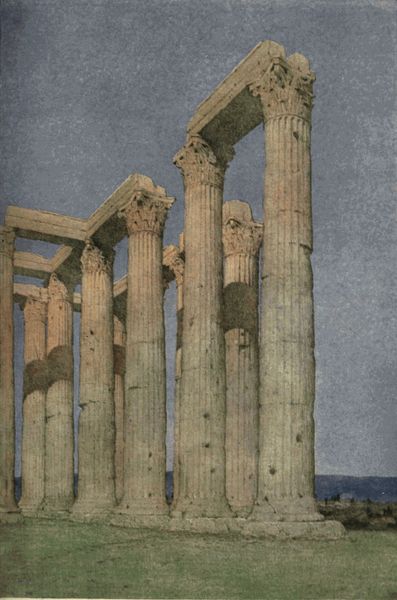

THE TEMPLE OF THE OLYMPIAN ZEUS AT ATHENS

THE TEMPLE OF THE OLYMPIAN ZEUS AT ATHENS

From this view you turn to behold the Parthenon. A writer who loved Greece more than all other countries, who was steeped in Greek knowledge, and who was deeply learned in archæology, has left it on record that on his first visit to the Acropolis he was aware of a feeling of disappointment. His heart bled over the ravages wrought by man in this sacred place—that Turkish powder-magazine in the Parthenon which a shell from Venetians blew up, the stolen lions which saw Italy, the marbles carried to an English museum, the statues by Phidias which clumsy workmen destroyed.

But so incomparably noble, so majestically grand is this sublime ruin, that the first near view of it must surely fill many hearts with an awe which can leave no room for any other feeling. It is incomplete, but not the impression it creates.

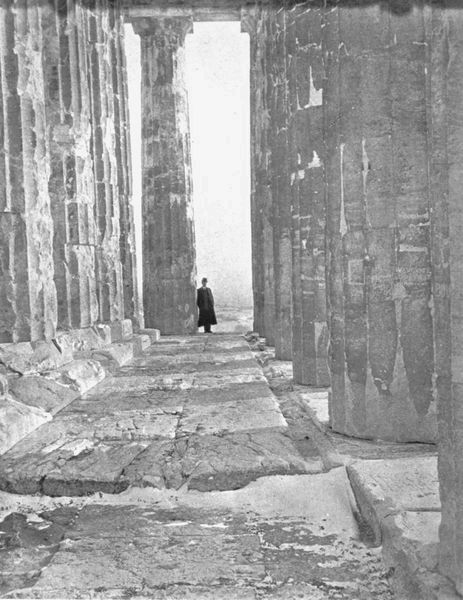

The Parthenon, as it exists to-day, shattered, almost entirely roofless, deprived of its gilding and color, its glorious statues, its elaborate and wonderful friezes, its lions, its golden oil-jars, its Athene Parthenos of gold and ivory, the mere naked shell of what it once was, is stupendous. No memory of the gigantic ruins of Egypt, however familiarly known, can live in the mind, can make even the puniest fight for existence, before this Doric front of Pentelic marble, simple, even plain, but still in its devastation supreme. The size is great, but one has seen far greater ruins. The fluted columns, lifted up on the marble stylobate which has been trodden by the feet of Pericles and Phidias, are huge in girth, and rise to a height of between thirty and forty feet. The architrave above their plain capitals, with its projecting molding, is tremendously massive. The walls of the cella, or sanctuary of the temple, where they still remain, are immense. But now, where dimness reigned,—for in the days when the temple was complete no light could enter it except through the doorway,—the sunlight has full possession. And from what was once a hidden place the passing traveler can look out over land and sea.

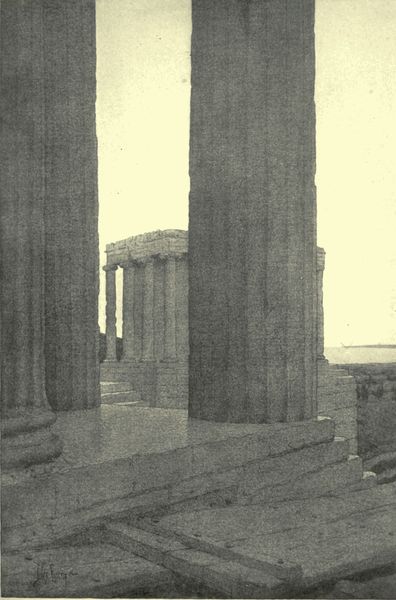

IN THE PORTICO OF THE PARTHENON

IN THE PORTICO OF THE PARTHENON

Some learned men have called the Parthenon severe. It is wonderfully simple, so simple that it is not easy to say exactly why it produces such an overpowering impression of sublimity and grandeur. But it is not severe, for in severity there is something repellent, something that frowns. It seems to me that the impression created by the Parthenon as a building is akin to that created by the Sphinx as a statue. It suggests—seems actually to send out like an atmosphere—a tremendous calm, far beyond the limits of any severity.

The whole of the Parthenon, except the foundations, is of Pentelic marble. And this marble is so beautiful a substance now after centuries of exposure on a bare height to the fires of the sun, to the sea-winds and the rains of winter, that it is impossible to wish it gilded, and painted with blue and crimson. From below in the plain, and from a long distance, the temple looks very pale in color, often indeed white. But when you stand on the Acropolis, you find that the marble holds many hues, among others pale yellow, cocoa color, honey color, and old gold. I have seen the columns at noonday, when they were bathed by the rays of the sun, glow with something of the luster of amber, and look almost transparent. I have seen them, when evening was falling, look almost black.

The temple, which is approached through the colossal marble Propylæa, or state entrance, with Doric colonnades and steps of marble and black and deep-blue Eleusinian stone, is placed on the very summit of the Acropolis, at the top of a slope, now covered with fragments of ruin, scattered blocks of stone and marble, sections of columns, slabs which once formed parts of altars, and broken bits of painted ceiling, but which was once a place of shrines and of splendid statues, among them the great statue of Athena Promachos, in armor, and holding the lance whose glittering point was visible from the sea. The columns are all fluted, and all taper gradually as they rise to the architrave. And the flutes narrow as they draw nearer and nearer to the capitals of the columns. The architrave was once hung with wreaths and decorated with shields. The famous frieze of the cella, which represented in marble a great procession, and which ran round the external wall of the sanctuary, is now in pieces, some of which are in the British Museum, and some in Athens. A portion of this frieze may still be seen on the west front of the temple. The cella had a ceiling of painted wood. On one of its inner walls I saw traces of red Byzantine figures, one apparently a figure of the Virgin. These date from the period when the Parthenon was used as a Christian church, and was dedicated to Mary the mother of God, before it became a mosque, and, later, a Turkish powder-magazine. The white marble floor, which is composed of great blocks perfectly fitted together, and without any joining substance, contrasts strongly with the warm hues of the inner flutes of the Doric columns. Here and there in the marble walls may be seen fragments of red and of yellow brick. From within the Parthenon, looking out between the columns, you can see magnificent views of country and sea.

Two other temples form part of the Acropolis, with the Propylæa and the Parthenon, the Temple of Athene Nike and the Erechtheum. They are absolutely different from the profoundly masculine Parthenon, and almost resemble two beautiful female attendants upon it, accentuating by their delicate grace its majesty.

The Temple of Nike is very small. It stands on a jutting bastion just outside the Propylæa, and has been rebuilt from the original materials, which were dug up out of masses of accumulated rubbish. It is Ionic, has a colonnade, is made of Pentelic marble, and was once adorned with a series of winged victories in bas-relief.

Ionic like the Temple of Nike, but much larger, the Erechtheum stands beyond the Propylæa, and not far from the Parthenon, at the edge of the precipice beneath which lies the greater part of Athens. A marvelously personal element attaches to it and makes it unique, giving it a charm which sets it apart from all other buildings. To find this you must go to the southwest, to the beautiful Porch of the Caryatids, which looks toward the Parthenon.

There are six of these caryatids, or maidens, standing upon a high parapet of marble and supporting a marble roof. Five of them are white, and one is a sort of yellowish black in color, as if she had once been black, but, having been singled out from her fellows, had been kissed for so many years by the rays of the sun that her original hue had become changed, brightened by his fires. Four of the maidens stand in a line. Two stand behind, on each side of the portico. They wear flowing draperies, their hair flows down over their shoulders, and they support their burden of marble with a sort of exquisite submissiveness, like maidens choosing to perform a grateful and an easy task that brings with it no loss of self-respect.

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENE NIKE AT ATHENS

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENE NIKE AT ATHENS

I once saw a great English actress play the part of a slave girl. By her imaginative genius she succeeded in being more than a slave: she became a poem of slavery. Everything ugly in slavery was eliminated from her performance. Only the beauty of devoted service, the willing service of love,—and slaves have been devoted to their masters,—was shown in her face, her gestures, her attitudes. Much of what she imagined and reproduced is suggested by these matchlessly tender and touching figures; so soft that it is almost incredible that they are made of marble, so strong that no burden, surely, would be too great for their simple, yet almost divine, courage. They are watchers, these maidens, not alertly, but calmly watchful of something far beyond our seeing. They are alive, but with a restrained life such as we are not worthy to know, neither fully human nor completely divine. They have something of our wistfulness and something also of that attainment toward which we strive. They are full of that strange and eternal beauty that is in all the greatest things of Greece, from which the momentary is banished, in which the perpetual is enshrined. Contemplation of them only seems to make more deep their simplicity, more patient their strength, and more touching their endurance. Retirement from them does not lessen, but almost increases, the enchantment of their very quiet, very delicate spell. Even when their faces can no longer be distinguished and only their outlines can be seen, they do not lose one ray of their soft and tender vitality. They are among the eternal things in art, lifting up more than marble, setting free from bondage, if only for a moment, many that are slaves by their submission.

About two years ago this temple was carefully cleaned, and it is very white, and looks almost like a lovely new building not yet completed. Here and there the white surface is stained with the glorious golden hue which beautifies the Parthenon, the Propylæa, the Odeum of Herodes, the Temple of Theseus, the Arch of Hadrian, and the Olympieion. The interior of the temple is full of scattered blocks of marble. In the midst of them, and as it were faithfully protected by them, I found a tiny tree carefully and solemnly growing, with an air of self-respect. Above the doorway of the north front is some very beautiful and delicate carving. This temple was once adorned with a frieze of Eleusinian stone and with white marble sculpture. Its Ionic columns are finely carved, and look almost strangely slender, if you come to them immediately after you have been among the columns of the Parthenon. Majesty and charm are supremely expressed in these two temples, the Parthenon and the Erechtheum, the smaller of which is on a lower level than the greater. One thinks again of the happy slave who loves her lord.

The group of magnificent, gold-colored Greco-Roman columns which is called the Olympieion stands in splendid isolation on a bare terrace at the edge of the charming Zappeion garden. In this garden, full of firs and pepper-trees, acacias, palms, convolvulus, and pink oleanders, I saw many Greek soldiers, wearied out with preparations for the Balkan war against Turkey, which was declared while I was in Athens, sleeping on the wooden seats, or even stretched out at full length on the light, yellow soil. For there is no grass there. Beyond the Olympieion there is a stone trough in which I never saw one drop of water. This trough is the river-bed of the famous Ilissus!

The columns are very splendid, immense in height, singularly beautiful in color,—they are made of Pentelic marble,—and with Corinthian capitals, nobly carved. Those which are grouped closely together are raised on a platform of stone. But there are two isolated columns which look even grander and more colossal than those which are united by a heavy architrave. The temple of which they are the remnant was erected in the reign of Hadrian to the glory of Zeus, and was one of the most gigantic buildings in the world.

From the Zappeion garden you can see in the distance the snow-white marble Stadium where the modern Olympic and Pan-Hellenic games take place. It is gigantic. When full, it can hold over fifty thousand people. The seats, the staircases, the pavements are all of dazzling-white marble, and as there is of course no roof, the effect of this vastness of white, under a bright-blue sky, and bathed in golden fires, is almost blinding. All round the Stadium cypress-trees have been planted, and their dark-green heads rise above the outer walls, like long lines of spear-heads guarding a sacred inclosure. Two comfortable arm-chairs for the king and queen face two stelæ of marble and the far-off entrance. The earthen track where the sports take place is divided from the spectators by a marble barrier about five feet high, and till you descend into it, it looks small, though it is really very large. The entrance is a propylæum. It is a great pity that immediately outside this splendid building the hideous panorama should be allowed to remain, cheap, vulgar, dusty, and despicable. I could not help saying this to a Greek acquaintance. He thoroughly agreed with me, but told me that the Athenians were very fond of their panorama.

THE STADIUM, ATHENS

THE STADIUM, ATHENS

In a straight line with the beautiful Arch of Hadrian, and not far off, is the small and terribly defaced, but very graceful, Monument of Lysicrates, a circular chamber of marble, with small Corinthian columns, an architrave, and a frieze. It is surrounded by a railing, and stands rather forlornly in the midst of modern houses.

The Temple of Theseus, or more properly of Hercules, on the other side of the town, is a beautifully preserved building, lovely in color, very simple, very complete. It is small, and is strictly Doric and very massive. Many people have called it tremendously impressive, and have even compared it with the Parthenon. It seems to me that to do this is to exaggerate, to compare the very much less with the very much greater. There really is something severe in great massiveness combined with small proportions, and I find this temple, noble though it is, severe.

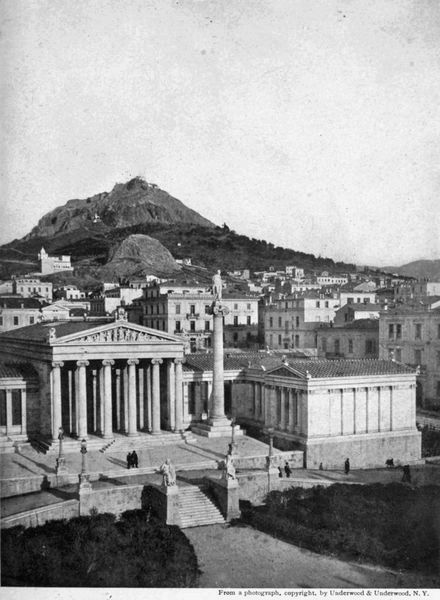

Athens contains several very handsome modern buildings, and one that I think really beautiful, especially on a day of fierce sunshine or by moonlight. This is the Academy, which stands in the broad and airy University Street, at whose mouth are the two cafés which Athenians call "the Dardanelles." It is in a line with the university and the national library, is made of pure white marble from Pentelicus, and is very delicately and discreetly adorned with a little bright gold, the brilliance of which seems to add to the virginal luster of the marble. The central section is flanked by two tall and slender detached columns crowned with statues. Ionic colonnades relieve the classical simplicity of the façade, with some marble and terra-cotta groups of statuary. The general effect is very calm, pure, and dignified, and very satisfying. The Athenians are proud, and with reason, of this beautiful building, which they owe to the generosity of one of their countrymen.

Modern Athens, despite its dust, is a delightful city to dwell in. Nobody in it looks rich,—that dreadful look!—and scarcely anybody looks poor. The king and the princes stroll casually about the streets, or may be met on the Acropolis or walking by the sea at Phalerum. I was allowed to wander all over the palace gardens, which are full of palms and great trees, and which resemble a laid-out wood. A Rumanian friend of mine told me that one day when he was in the garden, on turning a corner, he came upon the king and queen, with the crown-princess, who had just come down from the terrace in front of the royal apartments. All the center of the palace was burned out more than a year ago, and is now being slowly rebuilt. Greece is the home of genuine democrats, but democracy is delightful in Greece. Nobody thinks about rank, and everybody behaves like a gentleman. The note of Athens is a perfectly decorous liveliness, which is never marred by vulgarity. The stranger is welcomed and treated with the greatest possible courtesy, and he is never bothered by objectionable people such as haunt many of the cities of Italy, and of other lands where travelers are numerous. Athens indeed is one of the most simpatica of cities, wonderfully cheerful, simply gay, of a perfect behavior, yet unceremonious.

I have said that the Greeks are democrats. Nevertheless, like certain other democrats of whom one has heard, there are Greeks who love to think that they are not quite as all other Greeks. America, I am informed, has her "four hundred." Greece has her "fifty-two." In New York the "four hundred" consider themselves the advance-guard of fashion, if not of civilization. In Athens the "fifty-two" rejoice in a similar conviction. They do daring things sometimes. There is a card-game beloved of the Greeks called "Mouse." The fifty-two have introduced bridge and despise "Mouse." In Athens they frequent one another's houses. In the summer they "remove" to Kephisia in the pine-woods, where there are many pleasant, and some very fantastic, villas, and where picnics, tennis, and card-parties, theatrical performances and dances, fleet the hours, which are always golden, away. They are sometimes criticized by the "outsiders," for even gods are subject to criticism. People say now and then, "What will the fifty-two do next?" or, "Really there is no end to the folly of the fifty-two!" But have not similar remarks been heard even at Newport or upon Fifth Avenue pavements? Nevertheless, despite the fifty-two, you have only to look at the thin and decrepit palings of King George's garden to realize that at last you have found the true democracy, and a democracy sensible enough to understand the advantage of possessing a royal family. Every society needs a leader, and royalty leads far more effectively than any one else, however self-assured, however glittering. The Greeks are not without wisdom.

Their manners are charming and excellent. I had an unusual opportunity of putting them to the test. I was in Athens just before and just after the declaration of war against Turkey, when spies were everywhere, when a Turkish spy was discovered in Athens disguised as a Greek priest, and a woman was caught near Lycabettus in the act of poisoning the water-supply of the city. One morning early, when I was on the sea near Salamis in a small boat with a Greek fisherman, I was arrested on suspicion of being a spy, and was brought before the admiral in supreme command of the fleet. My passport was in Athens at my hotel, the admiral evidently disbelieved my explanations, and I was handed over to the police at the Piræus, accompanied by a report from the admiral in which, as was afterward made known to me, he stated that I was "a very suspicious character." And now to the test of Hellenic good manners.

THE ACADEMY, MOUNT LYCABETTUS IN THE BACKGROUND

THE ACADEMY, MOUNT LYCABETTUS IN THE BACKGROUND

Eventually a guard of police carrying rifles was sent to convey me from the Piræus to Athens, and in the middle of the afternoon I was obliged to walk as a prisoner through the streets of the Piræus, to take the tram to Phalerum, to get out there and wait for half an hour at a railway-station, and to travel in the train to Athens. In Athens I was made to walk three times, always guarded closely, through the principal streets and squares of the city, and twice past my hotel in the Constitution Square during the most busy hour of the day. Eventually, at night, I was released. Now, the Hellenes are considered by many people to be very inquisitive. During my public exposure as a prisoner I met with no really disagreeable curiosity from the crowd. Many people discreetly inquired of my guards who I was and what I had done, and naturally a great many more stared at me. But nobody followed me and my attendants as we marched on our way from one police station to another, to the War Office, etc. There was no pushing or jostling, such as there would certainly have been in an English town if a prisoner with guards was exposed to the public gaze. Curiosity was, as a rule, almost carefully dissembled, and inquiries were made with a charming discretion. I confess I felt grateful to the Greeks that day, though not to the admiral who had me arrested, or to the police who put me to so much inconvenience. And I was grateful for one thing more, that I was released just in time to see King George's arrival in Athens on the eve of the war.

The Hellenes are not an enthusiastic people, as a rule. They are critical, intellectual, sometimes rather cynical. But that night they gave way to emotion. Great crowds were lined up in Constitution Square, and were massed on the brow of the hill before the palace, when at length the police let me go. Darkness had long since fallen, but the square was illuminated brightly. All the balconies were packed with people. The terrace before the Grande Bretagne was black with sight-seers. And everywhere in the forefront were rows of eager, vivacious Greek children, many of them the soldiers of the future.

We had to wait for a very long time. But at last the king came in an open carriage, driving with "the Diádochos," as the crown-prince is always called in Greece. Both were in uniform. There was no ceremonial escort, so the people formed an unceremonial one. They ran with the carriage, shouting, waving their hats and handkerchiefs, cheering till they were hoarse, and crying, "War! War!" The great square rang with the clapping of thousands of hands. "Never before," said a Greek to me, "has the king had such a reception." When the carriages containing the rest of the royal family and the ministers had gone by, we ran in our thousands to the palace. Above the great entrance porch there is a balcony, and after a short time slim King George stepped out, rather cautiously, I thought, upon it, followed by all the princes and princesses. It was very dark, but a footman accompanied his Majesty, holding an electric light, and we had our speech.

THE ACROPOLIS AT ATHENS, EARLY MORNING

THE ACROPOLIS AT ATHENS, EARLY MORNING

The king read the first part of it in a loud, unemotional voice, bending sometimes to the light. But at the close he spoke a few words extempore, commending the Hellenic cause, if war should come, to the mercy of God. And then, again with precaution, he retired into the palace amid a storm of cheers.

I was afterward told that, with the whole of the royal family, his Majesty had been standing upon some loose planks which spanned an abyss. The royal palace, owing to the disastrous fire, is not yet what it seems. Fortunately, the Greek army has proved more solid, and the God of battles, so solemnly invoked by their king, has been favorable to the arms of the Greeks. No one, I think, who was in Greece during that time of acute tension, who saw the feverish preparations, the devotion of the toiling soldiers, the ardor of the volunteers; no one who witnessed, as I did, the return to Athens of the "American Greeks," who gave up everything and crossed the ocean to fight for their little, splendid country, could wish it otherwise.

The descendants of those who made the Parthenon have shown something of that Doric soul which is surely the soul of Greece.

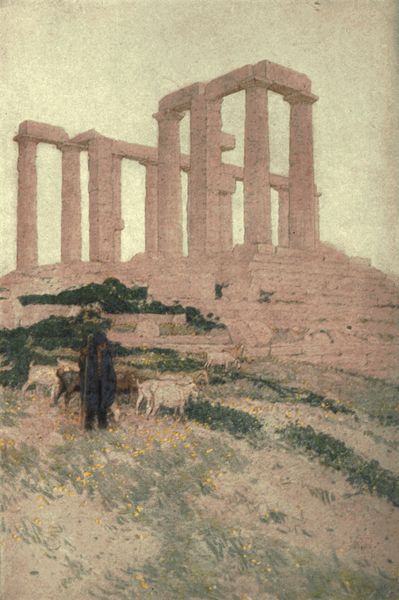

THE TEMPLE OF POSEIDON AND ATHENE AT SUNIUM

THE TEMPLE OF POSEIDON AND ATHENE AT SUNIUM

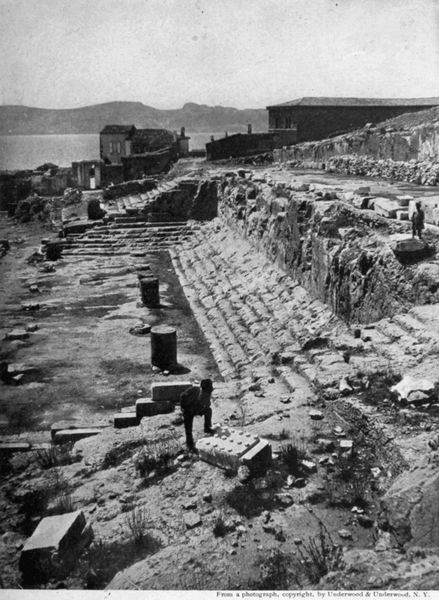

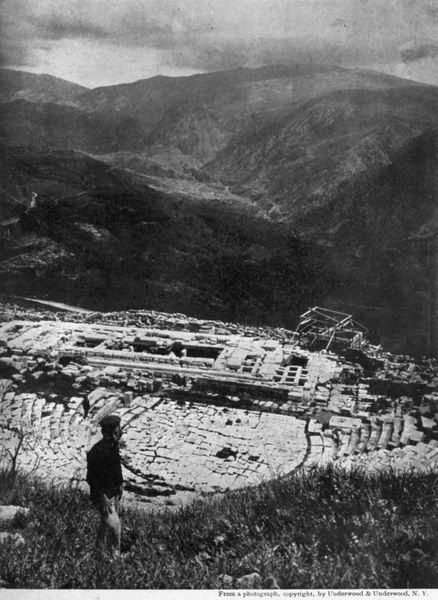

Upon the southern slope of the Acropolis, beneath the limestone precipices and the great golden-brown walls above which the Parthenon shows its white summit, are many ruins; among them the Theater of Dionysus and the Odeum of Herodes Atticus, the rich Marathonian who spent much of his money in the beautification of Athens, and who taught rhetoric to two men who eventually became Roman emperors. The Theater of Dionysus, in which Æschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides produced their dramas, is of stone and silver-white marble. Many of the seats are arm-chairs, and are so comfortable that it is no uncommon thing to see weary travelers, who have just come down from the Acropolis, resting in them with almost unsuitable airs of unbridled satisfaction.

It is evident to any one who examines this great theater carefully that the Greeks considered it important for the body to be at ease while the mind was at work; for not only are the seats perfectly adapted to their purpose, but ample room is given for the feet of the spectators, the distance between each tier and the tier above it being wide enough to do away with all fear of crowding and inconvenience. The marble arm-chairs were assigned to priests, whose names are carved upon them. In the theater I saw one high arm-chair, like a throne, with lion's feet. This is Roman, and was the seat of a Roman general. The fronts of the seats are pierced with small holes, which allow the rain-water to escape. Below the stage there are some sculptured figures, most of them headless. One which is not is a very striking and powerful, though almost sinister, old man, in a crouching posture. His rather round forehead resembles the very characteristic foreheads of the Montenegrins.

Herodes Atticus restored this theater. Before his time it had been embellished by Lycurgus of Athens, the orator, and disciple of Plato. It is not one of the gloriously placed theaters of the Greeks, but from the upper tiers of seats there is a view across part of the Attic plain to the isolated grove of cypresses where the famous Schliemann is buried, and beyond to gray Hymettus.

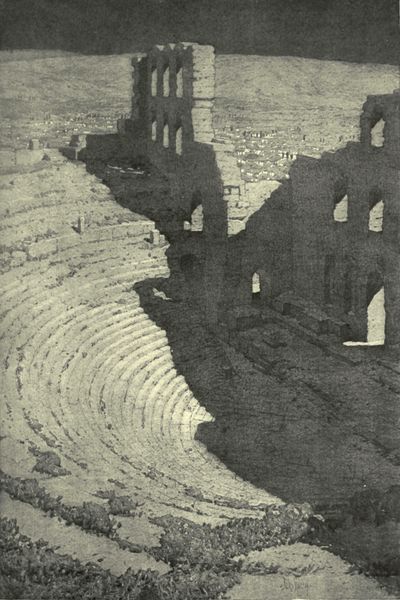

Standing near by is another theater, Roman-Greek, not Greek, the Odeum of Herodes Atticus, said to have been built by him in memory of his wife. This is not certain, and there are some authorities who think that, like the beautiful arch near the Olympieion, this peculiar, very picturesque structure was raised by the Emperor Hadrian, who was much fonder of Athens than of Rome.

The contrast between the exterior, the immensely massive, three-storied façade with Roman arches, and the interior, or, rather, what was once the interior, of this formerly roofed-in building, is very strange. They do not seem to belong to each other, to have any artistic connection the one with the other.

The outer walls are barbarically huge and heavy, and superb in color. They gleam with a fierce red-gold, and are conspicuous from afar. The almost monstrous, but impressive, solidity of Rome, heavy and bold, indeed almost crudely imperious, is shown forth by them—a solidity absolutely different from the Greek massiveness, which you can study in the Doric temples, and far less beautiful. When you pass beyond this towering façade, which might well be a section of the Colosseum transferred from gladiatorial Rome to intellectual Athens, you find yourself in a theater which looks oddly, indeed, almost meanly, small and pale and graceful. With a sort of fragile timidity it seems to be cowering behind the flamboyant walls. When all its blanched marble seats were crowded with spectators it contained five thousand persons. As you approach the outer walls, you expect to find a building that might accommodate perhaps twenty-five thousand. There is something bizarre in the two colors, fierce and pale, in the two sizes, huge and comparatively small, that are united in the odeum. Though very remarkable, it seems to me to be one of the most inharmonious ruins in Greece.

The modern Athenians are not very fond of hard exercise, and except in the height of summer, when many of them go to Kephisia and Phalerum, and others to the islands, or to the baths near Corinth for a "cure," they seem well content to remain within their city. They are governed, it seems, by fashion, like those who dwell in less-favored lands. When I was in Athens the weather was usually magnificent and often very hot. Yet Phalerum, perhaps half an hour by train from Constitution Square, was deserted. In the vast hotel there I found only two or three children, in the baths half a dozen swimmers. The pleasure-boats lay idle by the pier. I asked the reason of this—why at evening dusty Athens was crammed with strollers, and the pavements were black with people taking coffee and ices, while delightful Phalerum, with its cooler air and its limpid waters, held no one but an English traveler?

"The season is over," was the only reply I received, delivered with a grave air of finality. I tried to argue the matter, and suggested that anxiety about the war had something to do with it. But I was informed that the "season" closed on a certain day, and that after that day the Athenians gave up going to Phalerum.

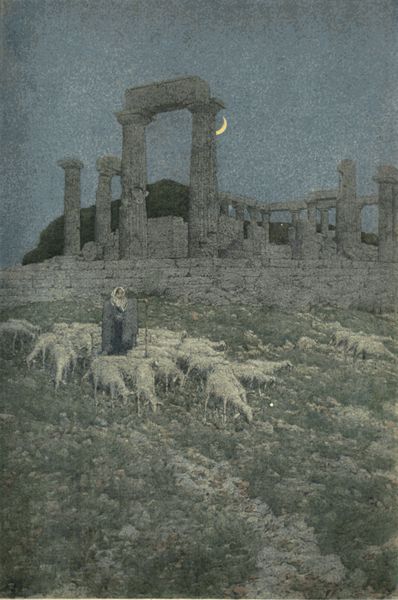

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENE, ISLAND OF ÆGINA

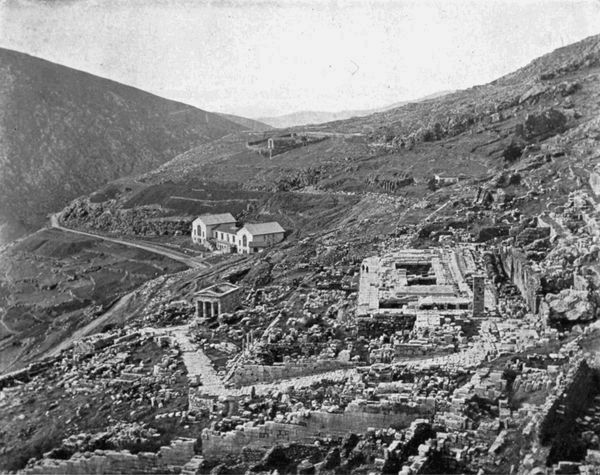

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENE, ISLAND OF ÆGINA