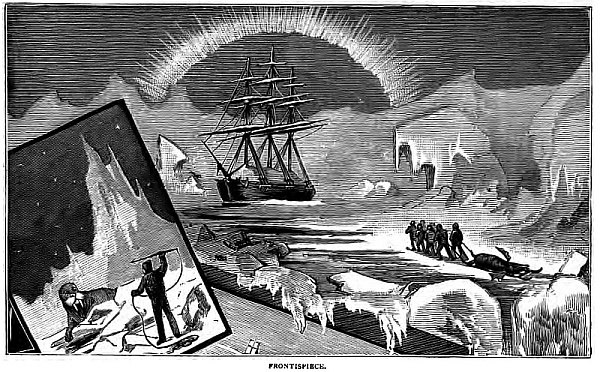

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Cruise of the Snowbird, by Gordon Stables

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

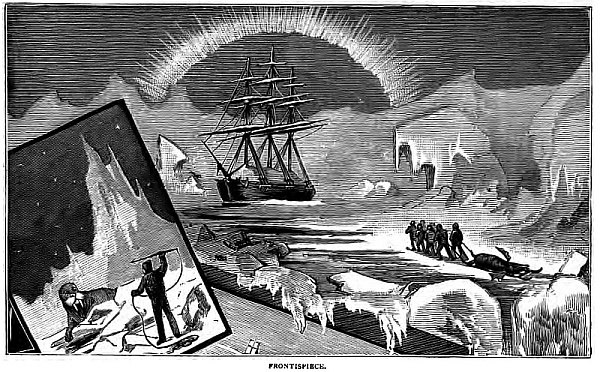

Title: The Cruise of the Snowbird

A Story of Arctic Adventure

Author: Gordon Stables

Illustrator: -

Release Date: December 11, 2011 [EBook #38276]

Last Updated: July 16, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CRUISE OF THE SNOWBIRD ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Gordon Stables

"The Cruise of the Snowbird"

"A Story of Arctic Adventure"

Chapter One.

The Young Chief of Arrandoon—The Rising Storm—Lost in the Snow.

It was winter. Allan McGregor stood, gun in hand, leaning against a rock half-way down the mountain-side, and, with the exception of himself and the stately deer-hound that lay at his feet, there was no sign of any living thing in all the glen; and dreary and desolate in the extreme was the landscape all around him. Glentroom in the summer time, when the braes were all green with the feathery birches, and the hillsides ablaze with the purple bloom of the heather, must have been both pleasant and romantic; but the birch-trees were now leafless and bare, the mountains were clad in snow, and the rock-bound lake, that lay far beneath, was leaden and grey like the sky itself, except where its waves were broken into foam by the snow-wind. That snow-wind blew from the north, and there was a sound in its voice, as it sighed through the withered breckans and moaned fitfully among the rocks and crags, that told of a coming storm.

Allan was the young laird of Arrandoon. All the glen had at one time belonged to his ancestors—ay, and all the land that could be seen, and all the lochs that could be counted from the peaks of Ben Lona. His father, but two short years before the commencement of this strange story of adventure, had died, sword in hand, at the head of his regiment in distant Afghan, and left him—what? A few thousand sheep, a few thousand acres of heather land on which to feed them, the title of chief, and yonder ancient castle, where dwelt his widowed mother and his sister.

Although he was a good Highland mile from his home, the castle, visible in every line and lineament from where he stood, formed quite a feature in the landscape. A tall grey building, with many a quaint and curious window, and many a turret chamber, it was built on the spur of the mountain, around which swept a brown hill-stream, the third side, or base of the triangle, being bounded by a moat now dry, and a drawbridge never raised. Far down beneath it was the grey loch, to which the noisy stream was hurrying.

Every old castle has its old story, and Arrandoon was no exception. It had been built in troublous times—built when the wild clans of the McGregors were in their glory. There the chiefs had dwelt, thence had they often sallied to tread the war-path or arouse the chase, and in its ancient halls many a gay revel had been held; but peace with the Lowlands, strange to say, had wrought the downfall of the chiefs of Arrandoon. The country had been thrown open, Englishmen had visited the glens, and friendships had been formed between those who once were deadly foes. In their own Highland homes the McGregors had entertained strangers in a regal fashion. Herein was pride—the pride that goes before a fall. When the chieftains went south, there, too, they would lord it, and herein lay more pride—the pride that caused the fall—for, alas and a lack-a-day! for the want of money land must be sold. Thus the stranger crept into the country of the Gael, and gold did for the proud McGregors, what the sword itself could never achieve—it laid them low.

That was one chapter of this castle’s story; the second is even a sadder one, for it tells of the days when, bereft of their lands, the proud chiefs of the McGregors, scorning trade, placed their claymores at the service of the reigning monarch, and fell in many a foreign land, fighting in a cause that was not their own, because fighting, they thought, was honourable, and fighting gave them bread. And their wives and their little ones were left at home to mourn. But no stranger saw the tears they shed.

It was towards this castle that the eyes of Allan McGregor were turned when first we see him; it was of the mournful history of his family he was thinking, as he stood on the hillside on this bleak, cold wintry evening.

“Bah!” he said to himself, “the very game seem to forsake the glen. Just look here,” he continued, addressing the dog, who looked up, wagging his tail, “only two hares and a brace or two of birds, with a wild cat that we shot at hazard, didn’t we, Bran? And I’m sure we’ve walked fully twenty miles, haven’t we, Bran?”

“Twenty miles fully,” Bran seemed to say, speaking with his eyes and his tail.

“And really, Bran, when my English college friends come to see me—as they will to-night, you know—I’ll hardly have anything to give them to eat, leaving sport out of the question; will I, Bran?”

Bran looked very serious at this, for he knew every inflection of his master’s voice.

“Ah, Bran, Bran! my dear old dog! it is very hard being a Highland chieftain with nothing to support one’s dignity on. Dignity, indeed! Why, Bran, I have positively to put mine in the pot and boil it for dinner. Now rouse up, Bran; I want to speak to you, because I must have somebody to open my heart to.”

Bran sat up on his haunches, and young Allan placed his hand on his head.

“Yes, Bran, my heart seems strangely full of something, and I think, old dog, that it is hope! hope for better times to come. You see our castle home down yonder, Bran?”

The noble hound looked in the direction indicated, and again moved his tail.

“Well, Bran, for many, many years there hasn’t been a single wreath of smoke seen above any of the chimneys of that bonnie old house, except those that rise from the southern wing—the smallest wing, Bran, remember—and all the rest of the castle is going to wreck and ruin. No wonder you half close your eyes, Bran; it is a sad serious business, and fine times the mice and the rats and the owls and the bats have been having in it, I can tell you!

“But now just listen, old fellow! All the time that you have been snoozing among the snow there, with your nose on top of the game-bag, I have been standing here thinking—thinking—thinking.

“You would like to know what I have been thinking about, wouldn’t you? Well, as you’re a good, faithful dog, I’ll tell you. I’ve been thinking about the past, and old, old times, when McGregor of Arrandoon was the proudest chief that ever trod the heather. That is more than a hundred years ago, Bran. The present chief of Arrandoon is a very different sort of an individual. To tell you the truth, my friend, your master is just as poor as peastraw, and there isn’t much substance in that. But, oh! Bran, I’ve been thinking that, what if I myself, by my own exertions, could go somewhere and do something that would earn me wealth and fame? To be sure I would like to be a soldier, but then mother says I must not leave her for the wars, and my poor father fought and bled for twenty long years, and there was nothing to send home but his sword. Heigho! No, I cannot be a soldier, even if I would. But something, Bran, I mean to do; something I mean to be, Bran. I don’t know yet, though, what that something will be, but my mother shall not die in poverty; of that I feel quite certain. Pride caused the fall of the chiefs of Arrandoon; pride shall raise us once again. The song says,—

“‘Whate’er a man dares he can do.’

“And I mean to dare and I mean to do, even if I go off to the gold-diggings. But, oh! Bran, only to think of getting back even a portion of my lands, that are now turned into shooting-grounds for the alien and stranger, to see sheep and lowing kine grazing where now only the heather grows, and the smoke curling upwards once more, from every chimney of our dear old home! Isn’t it a glorious thought, Bran?”

Bran jumped up at once and shook himself. Poor dog! he had no knowledge of a world beyond the glen, and probably the words in his master’s heroic speech that he understood the best, were those about going somewhere and doing something.

So he shook himself, wagged his tail, looked up to the sky, down at the castle, then all round him, and finally up into his master’s face, saying plainly enough,—

“By all means, master. I’m ready if you are. What is it to be—hares, rabbits, deer, or wild cat? I’m ready.”

Young Allan laughed aloud, and again patted the rough honest head of the faithful hound. And a very nice picture he and the dog would, just at that moment, have made, had an artist been there to transfer it to canvas. McGregor was poor, I grant you, but he owned something better even than riches: he had youth and health and beauty—the beauty of manliness, and his were a face and figure that once seen were sure to be remembered.

“Tall and stately, and strong as the oak, graceful as the bending willow,”—this is something like the language that Ossian, or any other ancient Celtic bard, might have used in describing him. I am sorry that I am not a Celtic bard, and that I must content myself with prosaically saying that Allan was handsome, and that the Highland garb which he wore—perhaps the most romantic of all costumes—well became him.

Reader, did ever you run down a mountain-side? I can tell you that it is glorious fun. You must know your mountain well though, and be sure no precipices are in your way. Having made certain of this, off you go, just as Allan and his hound went now, with wild skips, and hops, and jumps; it is not running, it is positive kangarooing, and when you do leave the ground in a leap, you think you will never touch it again. But no fear must dwell in your heart during this mad race. Once commenced, nothing can stop your wild career, till you find yourself at the foot and on level ground; and even then you have to run a goodly distance to expend the impulse that carried you downwards, or else you will tumble. But when you have stopped at last, and gazed upwards, “Is it possible,” you say to yourself, “that I can have descended from such a height in so short a space of time?”

I do not know whether Bran or his master was at the foot of the mountain first, but I do happen to know that they both disappeared in a wreath of snow as soon as they got there, and that both of them emerged therefrom laughing. After that, Allan McGregor sloped his gun and walked on more sedately, as became the chief of Arrandoon.

And now he approached the old castle, which looked ever so much higher and more imposing as one stood beneath it. He fired both barrels of his gun in the air, and the sound reverberated from hill and crag, rolling far away over the loch itself in a thousand echoes, as if the fairies were engaged at platoon-firing. Bran barked, and his bark was re-echoed too, not only from the rocks around, but from the interior of the castle walls. This last, I must tell you, was an Irish echo; it was no ghostly recoil of Bran’s own voice, but the genuine outcome from canine lungs; and lo! yonder come the owners of them, pouring over the bridge, a perfect hairy hurricane, to welcome Bran and his master home. Two Highland collies, a lordly Saint Bernard, a whole pack of what looked like stable brooms, but were in reality Skye terriers, and last, but not least, Bran’s old mother.

When the hubbub and din were somewhat settled, and the greetings over, Allan proceeded to cross the bridge, and McBain, his foster-father, advanced with a kindly smile to meet him.

I must introduce McBain to the reader without more ado—that is, I must give you some idea of his appearance; as to his character, that will develop itself as the story proceeds. He was about the middle height, then, and clad, like Allan, in the Highland dress of McGregor tartan—or plaid, as the English and Lowland Scotch erroneously call it. Though far from old, McBain was grey in beard and furrowed in brow; yet there are but few young men, I ween, who, had they ventured on a tussle with that broad-shouldered, wiry Highlander, would have cared to repeat the experiment for a week to come at least.

This was Allan’s foster-father. He had been in the family since he was a child, and his ancestors, like himself, had been chief retainers to the lairds of Arrandoon. He was a right faithful fellow, and a Scotchman in everything, thinking no people so good or brave or powerful as his own, nor any other country in the world worth living in; and from this you will readily infer that he had never mixed very much with the peoples of the earth. This is true; and still he had travelled when a young man, but it was towards the desolate regions of the North Pole. It was pride had taken him there—a cross word that his father had said to him, and young McBain had gone to sea. Only, a few years of the wild, rough life he had led on the icy ocean around Spitzbergen had taught him that there was no place like home, so he returned to it and received his father’s pardon, and, later on, his blessing.

“Aha, Allan, boy!” cried McBain; “so you’ve got back at last. Indeed—indeed we thought you were lost, and Bran and all. What sport, boy—what sport?”

“There is the bag,” said Allan, “and precious little you’ll find in it.”

“Ah! But, boy, half a loaf is better than no bread. When I was in Spitzbergen—”

“There, there,” said Allan, interrupting him, “never mind about Spitzbergen now; but tell me, have Ralph and Rory come, there’s a good old foster-father.”

“Ralph and Rory come!” replied McBain, with an air of surprise. “Why, they are English, Allan; and do you think they’d leave the hospitality and good cheer of an Inverness hotel, to visit Glentroom in such weather as this? It isn’t likely!”

Allan was silent; he had turned away his head and was gazing skywards, with something very like a frown on his face.

McBain laid a kindly hand on his shoulder. “You are piqued, son,” he said; “you are angry. There is the proud, defiant look of the McGregor chiefs on your countenance. Let it pass, Allan; let it pass. Do not forget for a moment what the McBains have ever been to your people. Have they not served them well, and fought and bled for them too? Were they not ever the first at the castle walls, when the fiery cross was sent through the glen? Do not forget that I have been a true foster-father to you, my son? Haven’t I taught you all you know? on the hills, on the lochs, and by the river? and would you get angry with the old man because he says your guests will hardly dare turn up to-night?”

Allan passed his hand quickly across his brow, as if to brush away a cloud.

“No, no!” he replied; “I’m not angry. Only—only you don’t know my English friends; you will alter your opinion of them when you do. They are brave and manly fellows, McBain. Ralph rowed stroke oar in his boat at Cambridge, and Rory is the best bowler in the three royal counties.”

McBain laughed.

“Allan! Allan!” he said; “think you for a moment they could do what I have taught you to do? Could either of them cross Loch Kreenan in a cobble when the waves are houses high, when their white crests cut the face like a Highland dirk? Could they bring the eagle from the clouds with a single bullet, or the windhover from the sky? Could they grapple with and gralloch a wounded red deer? Nay; and even if they could, if they were as brave and strong and fierce as the wild cat of the mountain, it would take all their strength and all their courage to face the storm that is brewing to-night. See, Allan, the clouds are already settling down on the hills, the peak of Melfourvounie is buried in mist, there is a mournful sough in the rising wind, and ere five hours are over the boddach will be shrieking among the crags of Drontheim.”

(Boddach—A spirit, believed in by many, who takes the shape of an old man, sometimes seen by night in the woods, but always heard shrieking among the rocks that he haunts whenever storms are raging.)

“All the more reason,” cried Allan, talking rapidly, “that I should go and meet them. Tell mother and sister I have gone a little way down the glen to meet Ralph and Rory, and we’ll all be back to dinner. Bran and Oscar will go with me. But stay, don’t you hear the bagpipes? It is Peter, and very likely my friends are with him.”

The sound came nearer and nearer, and presently out from the shadows of the dark pine-wood strode Peter—all alone.

Both went quickly to meet him, and Peter’s story was soon told.

“The Sassenach gentlemans,” he said, “had both left Inverness with him in the morning, and fine young gentlemans they were, and might have been Highlanders for the matter of that. But och and och! they would take the high road for sake of the scenery, bless you, and he had to take the low; but for all that they ought to have been at the castle hours and hours ago.”

Young Allan and his foster-father said never a word; they did but tighten their hands, and glance for a moment in each other’s eyes, yet both understood that the simple action implied a promise on either side to stand together, shoulder to shoulder, whatever might happen.

Presence of mind in emergency is a gift that seems peculiar to the Scottish Highlander. Born in a mountain land, and accustomed from his very infancy to face every danger in hill or glen, in flood or fell or field, his true character is never better seen than in times of danger. McBain waited for a few minutes in the castle courtyard until Allan, who had hurried away, should have time to communicate with his mother and sister; then he struck a gong, and while yet its thunders were reverberating among the hills, he was surrounded by every servant in the place, old Janet, the cook, not excepted; then the orders that fell calmly and yet quickly from his lips showed at once that he was master of the situation.

“Janet, old woman,” he said, “run away to the house like a good creature and get ready the dinner; the best that ever you made, do ye hear? Peter, run, lad, and get a rope, the crooks, and lanterns. Here, take the chief’s gun. Yes, certainly, bring the bagpipes, and don’t forget the flask. Donald Ogg, get the pony put in the trap, with rugs and plaids galore. Take the high road to Inverness and follow us soon. Thank you, Peter. Now for the dogs. No, no; not a pack. Back with them all to the kennel save Oscar, Bran, and Kooran the collie. Here we are, Allan, boy, all ready for a start.”

And in less time than it takes me to tell it, the little expedition was equipped and started. A few minutes more and they had disappeared in the pine forest from which Peter had so lately emerged, and the old Castle of Arrandoon was left to silence and the gloom of quickly-descending night.

Chapter Two.

Saved—Rory and Ralph—McBain has an Idea.

There is probably no music in the world more spirit-stirring—when heard amongst the native hills—than that of the Highland bagpipe. How often it has led our Scottish troops to victory, and cheered their drooping hearts in times of trouble, let history tell. In the London streets the sound of the pipes may be something vastly different, and then the pipers get undue blame.

The little party who left the Castle of Arrandoon to go in search of Ralph and Rory did well to have Peter and his bagpipes included in their number, for, so long as they were within hearing distance of the castle, the music would give hope to those left behind; and when beyond that, it would not only serve to while away the time of the searchers, but even in the darkness it might perchance be heard by the sought.

The road they had taken led upwards through the pine forest for more than a mile, and even when it left the wood it still ascended, until it at last joined the old highway to Inverness. This was quite high up among the mountains—so high, indeed, that even the most distant peaks were visible on the other side of the lake.

“Surely,” said McBain, “we shall meet your friends ere long.”

“I fear the very worst,” said Allan, gloomily, “for, had they not left the road for some purpose or another, they would have reached the glen long before this time. Rory would have his sketch-book, and both of them are fond of wild scenery.”

“Wild scenery indeed!” said McBain; “they needn’t leave the road to search for that.”

His words were surely true, for a grander scene than that around them it would be difficult to imagine.

It was a toilsome road they had to trace though, for the untrodden snow lay a good foot deep on the path, and, albeit they cast many a longing look ahead, they had but little time and little heart to look around to admire the scenery. And the snow was dry and treacherous. It lay lightly on the brae-sides, and on the bending heather stems, apparently awaiting only the breath of the storm to raise it into clouds of whirling drift, and drive it into deep and impassable wreaths.

For more than an hour they trudged onwards without catching sight or hearing sound of life, whether of man, or bird, or beast. The wind, too, was beginning to rise, a few flakes of snow had begun to fall, and night and darkness were already settling down in the hollows and glens, and only on the hilltops did daylight remain.

At last they came to a shepherd’s hut, and McBain knocked loudly at the door.

“Are you in, Donald? Are you in?” he cried.

“To be surely I’m in,” said a tall, plaided Highlander, opening the little door; “to be surely I’m in, Mr McBain, and where else is it I’d be, I wonder, in such a night as it soon will be?”

“Have you been abroad to-day, Donald?” asked Allan.

“Abroad? Yes, looking after the sheepies, to be surely.”

“Have you seen or met any one?”

“Yes, yes; two English bodies, to be surely. One would be sitting on a stone, making a picture, and the other would be looking over his shoulder, as it were. Och! Yes, to be surely.”

“Would you go with us, Donald?” asked Allan, “and show us the spot where you saw them.”

“Would I go with you? Is it that you are asking me?” cried Donald; “and what for do you ask me? Why didn’t you tell us to go? Didn’t my poor brother go with your father? ay, and die by his side. Yes, Donald will go with you to the end of the world if you’ll want him. Wait till I get my crook; to be surely I’ll go.”

Donald disappeared as he spoke, but after about a minute he joined our friends, and they journeyed on together.

“It will be an awful night, to be surely,” said Donald, “and troth, it is more than likely the two English bodies are dead, or drowned, or frozen by this time. An’ och! it’s a blessing they are only English bodies.”

Such a speech as this did not tend to reassure young Allan. In very truth it almost quenched the hopes that were beginning to rise in his heart.

Donald was now their guide, and they were not surprised to observe that before very long he deserted the main road entirely, for a steep and craggy path that led downwards towards the distant lake. Along this narrow footway Donald bounded along with almost the speed of a red deer. Nor were Allan and his trusty companions slow to follow, for all felt how precious were the few minutes of daylight that were left to them.

And now the shepherd stops, removes his cap, and, passing his fingers through his hair in a puzzled kind of manner, stares around him in some surprise.

“Yes, yes,” he says at last; “this is the place, to be surely, but I don’t see a sign of the English bodies whatsomever.”

But if he does not, Allan McGregor, quicker of eye, does. He springs lightly forward, and picks something up that lies half-buried among the snow.

“It is Rory’s sketch-book,” he says, “Alas! poor Rory.”

But what is that mournful wail that now rises up towards them, apparently from the very bosom of the dark lake itself?

“It’s the boddach of Drontheim,” falters the shepherd, trembling like an aspen leaf. “It’s the boddach, to be surely, och! and och! What will become of us whatsomever?”

“Silence, Donald, silence?” cries McBain, as the strange sound falls once more on their listening ears. “Where is Oscar? Not here? Why, it is he! Come, men! Come, Allan, for, dead or alive, your friends are down yonder.”

They follow the footprints of the noble dog, although they are hardly visible, but Kooran, the collie, takes up the scent and does excellent service. So down the steep and craggy hill they rush, often stumbling, sometimes falling, but still going bravely on, and cheering Oscar with their voices as they run. At the foot at last, and on level ground, they hasten forward, welcomed by the Saint Bernard to a spot where lie two inanimate human forms, partly hidden by the lightly drifting snow.

Dead? No, thank Heaven! they are not dead, and what joy for Allan McGregor, when stalwart Ralph sits up, rubs his eyes, and gazes vacantly and wildly around him.

“Drink,” says McBain, holding a flask to his lips. The young Englishman swallows a mouthful almost mechanically, then staggers to his feet Allan and McBain steady him by the arms till he comes a little more to himself.

“Ralph, old fellow,” says Allan, “don’t you know me?”

“Yes, yes,” he mutters, hardly yet sensible of his surroundings, “I remember all now. Rory—the cliff—I could not raise him—sleep stole my senses away. But we are saved, are we not, and by you, good Allan, and by you strangers? But see to Rory, see to Rory.”

McBain was chafing Rory’s hands, and rubbing his half-frozen limbs.

“No,” he said, “not saved by us. You have Providence to thank, and yonder brave dog. Had he not found you, the sleep that had overcome you would have been your last.”

It was a long time, and it seemed doubly long to Allan and Ralph, ere Rory showed the slightest signs of returning life. At length, however, the blood began to trickle slowly from a wound he had received in the forehead in his fall over the cliff, and next moment he sighed deeply, then opened his eyes.

“God be praised?” said McBain, fervently; “and now, my friends, let us carry him.”

This was very easily done, for Rory was a light weight. So with Donald in front, and the dogs capering and barking all around them, the party commenced the ascent, and half-an-hour afterwards they were safe at the shepherd’s hut. And none too soon, for night was now over all the land, and the snow fell thick and fast.

Rory was laid upon the shepherd’s dais, and Allan and Donald proposed moving it close to the fire. But McBain knew better.

“No, no, no!” he cried, “leave him where he is. Never take a frozen man near the fire. I learned that at Spitzbergen. He has young blood in his veins, and will soon come round.”

But Rory, for a time, lay quiet enough. He was very white too, and but for his regular and uninterrupted breathing, and the tinge of red in his lips, one might have thought him dead.

“Poor little Rory!” said Allan, smoothing his dark hair from off his brow. “How cold his forehead is!”

Very simple words these were, yet there was something in the very tone in which they were uttered that would have convinced even a stranger, that Allan McGregor bore for the youth before him quite a brother’s love.

And who was Rory, and who was Ralph? These questions are very soon answered. Roderick Elphinston and Ralph Leigh were, or had been, students at the University of Cambridge. They had been “inseparables” all through the curriculum, and firm friends from the very first day they had met together. And yet in appearance, and indeed in character, they were entirely different. Ralph was a great broad-shouldered, pleasant-faced young Saxon Rory was small as to stature, but lithe and wiry in the extreme; his face was always somewhat pale, but his eyes had all the glitter and fire of a wild cat in them. Well, then, if you do not like the “wild cat,” I shall say “poet”—the glitter and fire of a poet. And a poet he was, though he seldom wrote verses. Oh! it is not always the verses one writes that prove him to be a poet. Very often it is just the reverse. I know a young man who has written more verses than would stretch from Reading to Hyde Park, and there is just as much poetry in that young man’s soul as there is in the flagstaff on my lawn yonder. But Rory’s soul was filled with life and imagination, a gladsome glowing life that could not be restrained, but that burst upwards like a fountain in the sunlight, giving joy to all around. Everything in nature was understood and loved by Rory, and everything in nature seemed to love him in return; the birds and beasts made a confidant of him, and the very trees and the tenderest flowerets in garden or field seemed to whisper to him and tell him all their secrets. And just because he was so full of life he was also full of fun.

When silent and thinking, this young Irishman’s face was placid, and even somewhat melancholy in expression, but it lighted up when he spoke, and it was wonderfully quick in its changes from grave to gay, or gay to grave. It was like a rippling summer sea with cloud-shadows chasing each other all over it. Like most of his countrymen, Rory was brave even to a fault. Well, then, there you have his description in a few words, and if you will not let me call him poet, I really do not know what else to call him.

Ralph Leigh I must dismiss with a word. But, in a word, he was in my opinion everything that a young English gentleman should be; he was straightforward, bold and manly, and though very far from being as clever as Rory, he loved Rory for possessing the qualities he himself was deficient in. Thoroughly guileless was honest Ralph, and indeed, if the truth must be told, he was not a little proud of his companion, and he was never better pleased than when, along with Rory in the company of others, the Irishman was what Ralph called “in fine form.”

At such times Ralph would not have interrupted the flow of Rory’s wit for the world, but the quiet and happy glance he would give round the room occasionally, to see if other people were listening to and fully appreciating his adopted brother, spoke volumes.

McBain was right. The young blood in Rory’s veins soon reasserted itself, and after half-an-hour’s rest he seemed as well as ever. His first action on awaking was to put his hand to his brow, and his first words were,—

“What is it at all, and where am I? Have I been in any trouble?”

“Trouble, Rory?” said Allan, pressing his hand. “Well, you and Ralph went tumbling over a cliff.”

“Only fifty feet of a fall, Rory,” said Ralph.

Rory sat bolt upright now, and opened his eyes in astonishment.

“Och! now I remember,” he said, “that we had a bit of a fall—But fifty feet! do you tell me so? Indeed then it’s a wonder there is one single whole bone between the two of us. But where is my sketch-book?”

“Here you are,” said Allan.

“Oh!” said Rory, opening the book, “this is worse than all; the prettiest sketch ever I made in my life all spoiled with the snow.”

“Now, boys,” continued Rory, after a pause, “I grant you this is a very romantic situation—everything is romantic bar the smoke; but what are we waiting for? and is this your Castle of Arrandoon, my friend?”

“Not quite,” replied Allan, laughing. “We are waiting for you to recover, and—”

“Well, sure enough,” cried Rory, “I have recovered.”

He jumped up as he spoke, kicked out his legs, and stretched out his arms.

“No; never a broken bone,” he said.

Now it had been arranged between Allan and McBain that Rory should ride in the cart, while they and Ralph should walk.

But Rory was aghast at such a proposal.

“What,” he cried; “is it a procession you’d make of me? Would you put me on straw in the bottom of a cart, like an old wife coming from a fair?”

“But,” persisted Allan, “you must be weak from the loss of blood.”

“Loss of blood,” laughed Rory, “don’t be chaffing a poor boy. If you’d seen the blood I lost at the last election, and all in the cause of peace and honour, too! No, indeed; I’ll walk.”

The storm was at its very worst when they once more emerged from the pine-wood, but every now and then they could see the light glimmering from one of the castle turrets, to guide them through the darkness. They sent the dogs on before to give notice of their approach; then Peter tuned up, and high above the roaring of the snow rose the scream of the great Highland bagpipe.

A few hours afterwards, the three friends had all but forgotten their perilous adventure among the snow, or remembered it only to make merry over it. It is needless to say that Allan’s mother and sister welcomed his friends, or that Ralph and Rory were charmed with the reception they received.

“Well,” said Rory, after the ladies had retired for the night, “I fully understand now what your poet Burns meant when he said—

“‘In heaven itself I’ll ask nae mair Than just a Highland welcome.’”

And now they gathered round the cosy hearth, on which great logs were blazing. McBain was relegated to an armchair in a corner, being the oldest Rory, who still felt the effects of his fall, reclined on a couch in front, with Ralph seated on one side and Allan on the other. Bran, the deer-hound, thought this too good a chance to be thrown away, so he got upon the sofa and lay with his great, honest head on Rory’s knees, while Kooran curled himself up on the hearthrug, and Oscar watched the door.

“Well,” said Ralph, “I call this delightful; and the idea of doing the Highlands in mid-winter is decidedly a new one, and that is saying a great deal.”

“Yes,” said Rory, laughing; “and a beautiful taste we’ve had of it to begin with. I fall over a cliff in the snow and Ralph comes tumbling after, just like Jack and Jill, and then we go to sleep like lambs, and waken with a taste of spirits in our mouths. Indeed yes, boys, it is romantic entirely.”

“Everything now-a-days,” said Ralph, with half a yawn, “is so hackneyed, as it were. You go up the Rhine—that is hackneyed. You go down the Mediterranean—that is hackneyed. You go here, there, and everywhere, and you find here, there, and everywhere hackneyed. And if you go into a drawing-room and begin to speak of where you’ve been and what you’ve done, you soon find that every other fellow has been to the same places, and done precisely the same things.”

“Sure, you’re right, Ralph,” said Rory; “and I do believe if you were to go to the moon and come back, some fellow would meet you on your return and lisp out, ‘Oh, been to the moon, have you! awfly funny old place the moon. Did you call on the Looneys when you were there? Jolly family the Looneys.’”

“There is a kind of metaphorical truth in what you say, Rory,” Ralph replied; “but I say, Allan, wouldn’t it be nice to go somewhere where no one—no white man—had ever been before, or do something never before accomplished?”

“It would indeed,” said Allan; “and I for one always looked upon Livingstone, and Stanley, and Gordon Cumming, and Cameron, and men like them, as the luckiest fellows in the world.”

“Now,” said Ralph, “I’m just nineteen. I’ve only two years more of what I call roving life, and if I don’t ride across some continent before I’m twenty-one, or embark at one end of some unknown river and come out into the sea at the other, I’ll never have a chance again.”

“Why, how is that?” said McBain.

“Well,” replied Ralph, “Sir Walter Leigh, my father, told me straight that we were as poor as Church mice, and that in order to retrieve our fortunes, as soon as I came of age I must marry my grandmother.”

“Marry your grandmother!” exclaimed McBain, half rising in his chair.

“Well, my cousin, then,” said Ralph, smiling; “she is five-and-forty, so it is all the same. But she has oceans of money, and my old father, bless him! is very, very good and kind. He doesn’t limit me in money now; though, of course, I don’t take advantage of all his generosity. ‘Go and travel, my boy,’ he said, ‘and enjoy yourself till you come of age. Just see all you can and thus have your fling. I know I can trust you.’”

“Have your fling?” cried Rory; “troth now that is exactly what my Irish tenants told me to do. ‘The sorra a morsel av rint have we got to give you,’ says they, ‘so go and have your fling, but ’deed and indeed, if we see you here again until times are mended, we’ll shoot ye as dead as a Ballyshannon rabbit.’”

“Well, young gentlemen,” said McBain, after a pause in the conversation, during which nothing was heard except the crackling of the blazing logs and the mournful moaning of the wind without, “you want to do something quite new. Well, I’ve got an idea.”

“Oh, do tell us what it is?” cried Ralph and Rory, both in one breath.

“No, no; not to-night,” said McBain, laughing; “besides, it wants working out a bit, so I’m off to bed to dream about it. Good night.”

“Depend upon it,” said Allan McGregor, as he parted with his friends at their chamber door, “that whatever it is, McBain’s idea is a good one, and he’ll tell us all about it to-morrow. You’ll see.”

Chapter Three.

Life at the Old Castle—McBain Explains his “Idea”—Allan’s Dream.

To say that our heroes, Ralph and Rory, were not a little impatient to know something about the scheme McBain was to propose for the purpose of giving them pleasure, would be equivalent to saying that they were not boys, or that they had men’s heads upon boys’ shoulders. So I willingly confess that it was the very first thing they thought about next morning, immediately after they had drawn up the blinds, to peep out and see what kind of a day it was going to be.

But this peeping out to ascertain the state of the weather was not so easily accomplished, as it would have been in the south of England. For fairy fingers seemed to have been at work during the night, and the panes were covered with a frost-work of ferns and leaves, more beautifully traced, more artistically finished, than the work of any human designer that ever lived. The whole seemed floured over with powdered snow. It was a pity, so thought Rory, to spoil the pattern on even one of the panes, but it had to be done, so by breathing on it for quite half a minute, a round, clear space was obtained; and gazing through this he could see that it was a glorious morning, that the clouds had all fled, that the sky was bluer than ever he had seen a sky before, that the wind was hushed, and the sun shining brightly over hills of dazzling white. The stems of the leafless trees looked like pillars of frosted silver, while their branches were more lovely by far than the coral that lies beneath the blue waves of the Indian Ocean.

“How different this is,” said Rory, “from anything we ever see in England! Ah! sure, it was a good idea our coming here in winter.”

“I wonder where McBain is this morning?” said Ralph.

“And I know right well,” said Rory, “what you’re thinking about.”

“Perhaps you do,” Ralph replied.

“Ay, that I do,” said Rory; “but don’t be an old wife, Ralph—never evince undue curiosity, never exhibit impatience. In other words, don’t be a squaw.”

“Oho!” cried Ralph, “now I see where the land lies. ‘Don’t be a squaw,’ eh? You’ve been reading Fenimore Cooper, you old rogue, you! The centre of a great forest in the Far West of America—midnight—a council of war—chiefs squatting around the camp fire—smoking the calumet—enter Eagle-eye—scats himself in silence—everybody burning to hear what he has to say, but no one dares ask for the world—ugh! and all that sort of thing. Am I right, Rory?”

“Indeed you are,” said the other, laughing; “you’ve bowled me out, I confess. But, after all, you know, it will be just as well not to seem impatient, and so I move that we never speak a word to McBain about what he said last night until he is pleased to open the conversation.”

“Right,” said Ralph; “and now let us go down to breakfast.”

Both Mrs McGregor and Allan’s sister Helen were very different from what Ralph and Rory had expected to find them. They had taken their notions of Highland ladies from the novels of Walter Scott and other literary worthies. Before they had come to Glentroom they had pictured to themselves Mrs McGregor as a kind of Spartan mother—tall, stately, dark, and proud, with a most exalted idea of her own importance, with an inexorable hatred of all the Saxon race, and an inordinate love of spinning. Her daughter, they had thought, must also be tall, and, if beautiful, of a kind of majestic and stately beauty, repellent more than attractive, and one more to be feared than loved. And they felt sure that Mrs McGregor would be almost constantly bending over her spinning-wheel, while Helen, if ever she condescended to bend over anything, which they had deemed a matter of doubt, would be bending over a very ancient piece of goods in the shape of a harp.

These were their imaginings prior to their arrival at the castle, but these ideas were all wrong, and very delighted were the young men to find them so. Here in Mrs McGregor was no stiff fastidious lady; she was a very woman and a very mother, loving her children tenderly, and devoted to their interests, and rejoiced to hold out the hand of welcome to her children’s friends. On the sunny side of fifty, she was slightly inclined to embonpoint, extremely pleasant both in voice and manner as well as in face. Rory first, and Ralph soon afterwards, felt as much at home in her presence and company as if they had known her all their lives.

As to Helen Edith, I do not think that any one would have been able to guess her nationality had they met her in society in town. She had been educated principally abroad, and could speak both the Italian and French languages, not only fluently, but, if I may be allowed the expression, mellifluently, for she possessed perfection of accent as well as exceeding sweetness of voice. She was rather small in stature, with pretty and shapely hands, and a nice figure.

Was she beautiful? you may ask me. Well, had you asked her brother he would have said, “Indeed, I never gave the matter a thought,” but Rory and Ralph would have told you that she was beautiful, and they would have added the words, “and sisterly.” I do not know whether or not Helen was a better or a worse musician than most young girls of her age—she was just turned seventeen. She sang sweetly, though not loudly; she never screamed, but sang with expression, as if she felt what she sang; and she accompanied herself on the harp. But as for Mrs McGregor’s spinning-wheel, why, our young heroes cast their eyes about in vain for it.

The portion of the castle now occupied by the McGregors was furnished in a far more luxurious style than probably accorded with their fallen fortunes, but everywhere there was evidence of refinement of taste. The old hall and the picture gallery delighted Rory most; he could fit a romance into every rusty coat of mail, and fix a poem to every spear and helmet.

“What a grand thing,” he said to Allan, “it is to have had ancestors! Never one had I, that I know of—leastways, none of them ever troubled themselves to sit for their portraits. More by token, perhaps, they couldn’t afford it.”

If Ralph enjoyed himself at the castle—and I might say that he undoubtedly did—he did not say a very great deal about it. To give vocal expression to his pleasure was not much in Ralph’s line, but it was in Rory’s, who, by the way, although nearly as old as his companion, was far more of a boy.

The feelings of the young chief of the McGregors, while showing his friends over the old castle, the ancient home of his fathers, were those of sadness, mingled with a very little touch of pride. Every room had its story, every chamber its tale—often one of sorrow; and these were listened to by Ralph and Rory with rapt attention, although every now and then some curious or quaint remark from the lips of the latter would set the other two laughing, and often materially damage some relation of events that bordered closely on the romantic.

“If ever I’m rich enough,” said Allan, leading the way into the ancient banqueting-hall, “I mean to re-roof and re-furnish the whole of the older portion of the castle.”

“But wherever has the roof gone to?” asked Rory, looking upwards at the sky above them.

“Fire would explain that,” replied Allan; “the whole of this wing of the building was burned by Cumberland in ’45—he who was surnamed the Bloody Duke, you know.”

“Were your people ‘out,’ as you call it, in ’45?” asked Ralph.

Allan nodded, and bit his lips; the memory of that terrible time was not a pleasant one to this Highland chief.

The little turret chambers were a source of both interest and curiosity to Allan’s companions.

“Bedrooms and watch-towers, are they?” said Ralph, viewing them critically. “Well, you catch a beautiful glimpse of the glen, and the hills, and woods, and lake from that little narrow window, with its solitary iron stanchion; but I say, Allan—bedrooms, eh? Aren’t you joking, old man? Fancy a great tall lanky fellow like me in a bedroom this size; why, I’d have to double up like a jack-knife!”

“Oh! look, Ralph, at these dark, mysterious stains on the oaken floor,” cried Rory—“blood, of course? Do you know, Allan, my boy, what particular deed of darkness was committed in this turret chamber?”

“I do, precisely,” replied Allan.

“Och! tell us, then—tell us!” said Rory.

“Ay, do,” said Ralph. “I shall lean against the window here and look out, for the view is delightful, but I’ll be listening all the same.”

“Well, then,” said Allan, “I made this little room my study for a few months last summer, and I spilt some ink there.”

“Now, indeed, indeed,” cried romantic Rory, “that is a shame to put us off like that. Never mind, Ralph; we know it is a blood-stain, and if Allan won’t tell us the story, then, we’ll invent one. Sure, now,” he continued, “I’d like to sleep here.”

“You’d catch your death of cold from the damp,” said Allan.

Rory wheeled him right round to the light, and gazed at him funnily from top to toe, and from toe to top.

“You’re a greater curiosity than the fine old castle itself,” said Rory; “and I don’t believe there is an ounce of romance in the whole big body of you. Now, if the place was mine, there isn’t a room—why, what is that?”

“That’s the gong,” said Allan, “and it says plainly enough, ‘Get r-r-r-r-ready for dinner.’”

“Well, but,” persisted Rory, “just before we go down below show us the corridor where the ghost walks at midnight, and the door through which it disappears.”

“A ghost!” said Allan; “indeed, I never knew there was one.”

“Ah! but,” Rory continued, “you never knew there wasn’t. Well, then, say probably there is a ghost, because you know, old fellow, in an ancient family like yours there must be a ghost. There must be some old fogey or another who didn’t think he was very well done by in this world, and feels bound to come back and walk about at midnight, and all that sort of thing. Pray, Allan, don’t break the spell. You’re welcome to the stains if you please, but ’deed and indeed, I mean to stick to the ghost.”

The first few days of their stay in Glentroom were spent in what Allan called “doing nothing,” for unless he left the castle for the hill, the river, or the lake, he did not consider he was doing anything. Within the castle walls, however, Rory for one was not idle. There was, in his opinion, a deal to be seen and a deal to be done: he had to make acquaintance with every living thing about the place—ponies and dogs, cattle and pigs, ducks, geese, fowl, and pigeons.

Old Janet averred that she had never seen such a boy in all her born days—that he turned the castle upside down, and kept all the “beasties” in an uproar; but at the same time she added that he was the prettiest boy ever she’d seen, and “Heaven bless his bonnie face,” which put her in mind of her dear dead boy Donald, and she couldn’t be angry with him, for even when he was doing mischief he made her laugh.

The parish in which Glentroom lies is a very wide one indeed, and contained at the time our tale opens many families of distinction. Nearly all of these were on visiting terms with the McGregors, and many a beautifully-fitted sledge used to drive over the drawbridge of Arrandoon Castle during the winter months—wheels, of course, were out of the question when the snow lay thick on the ground—so that life in Allan’s family, although it did not partake of the gaiety of the London season, was by no means a dull one, and both Ralph and Rory thought the evenings spent in the drawing-room were very enjoyable indeed. Ralph was a good conversationalist and a good listener: he delighted in hearing music, while Rory delighted to play, and, for his years, he was a violinist of no mean order. He had never been known to go anywhere—not even on the shortest of holiday tours—without the long black case that contained his pet instrument.

Now, as none of “the resident gentry,” as they were called, who visited at the castle have anything at all to do with our story, I shall not fatigue my readers by introducing them.

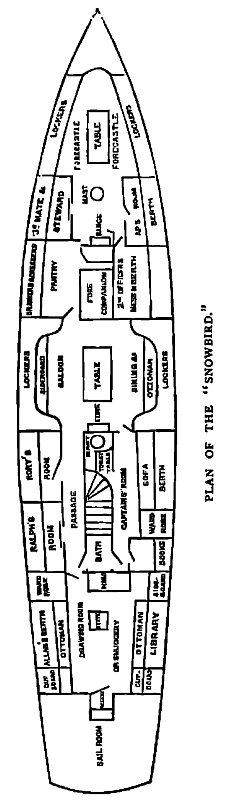

And why, it may be asked, should I trouble myself about describing life at the castle at all? And where is the Snowbird?—for doubtless you have guessed already that it is a ship of some kind. The Snowbird ere very long will sail majestically up that Highland lake before you, and in her, along with our heroes, you and I, reader, will embark, and together we will journey afar over the ocean wave, to regions hitherto but little known to man. Our adventures there will be many, wild, and varied, and some of them, too, so far from pleasant, that while exiled in the frozen seas of the far North, our thoughts will oftentimes turn fondly homewards, and we will think with a joy borrowed from the past of the quiet and peaceful days we spent in bonnie Arrandoon.

Ralph and Rory had kept the promise they had made to each other on the morning succeeding their arrival at Arrandoon; they left McBain to dream over his “idea” in peace. They did not behave like squaws, and I think it was the third or fourth evening before Allan’s foster-father said another word about it. They were then all around the fire, as they had been before; the ladies had retired, and the dogs were making themselves as snug and comfortable as dogs know how to whenever they get a chance.

“Well,” said McBain, after there had been a lull in the conversation for some little time, “we’ve been all so happy and jolly here for the last few days, that we haven’t had time to think much or to look ahead either; but now, if you don’t mind, young gentlemen, I will tell you what I should propose in the way of spending a few of the incoming spring and summer months, in what I should call a very pleasant fashion.”

“Yes,” cried Rory, “do tell us, we are burning to hear about it, and if it be anything new it is sure to be nice.”

“Very well,” said McBain. “Allan there tells me he means to stick to you both for a time—to keep you prisoners in Glentroom. He will trot you about for all that; you’ll be on parole, and roam about wherever you like; and you can fish and shoot and sketch just as much as ever you have a mind to. Meanwhile, buy a boat; I know where there is one to sell that will suit us in every way—a grand, big, strong, open boat. She belongs to Duncan Forbes, of Fort Augustus, and can be bought for an old song. We can have her round into the loch here. I’m a bit of a sailor, as Allan knows, and I’ll show you how to deck her over, set up rigging and mast, and make her complete, and I’ll make bold to say that before we have done with her she will be as neat and pretty a little craft as ever hauled the wind.”

“I say, boys,” said Rory, “I think the idea is a glorious one.”

“I must say, I like it immensely,” said Ralph.

“And so do I,” said Allan, “if—if we can all afford it.”

“Oh! but stop a little,” said McBain, “you haven’t heard all my proposal yet; the best of it is to come. Your cruising ground will be all up and down among the Western Islands, where the wildest and finest scenery in Europe exists. You’ll get any amount of fishing and shooting too, for wherever you three smart-looking young yachtsmen land on the coast, people will vie with each other in offering you Highland hospitality. And all the while you can make your pleasure pay you.”

“How—how—tell us how?”

“Why,” continued McBain, “around the rocky and rugged islands where you will be cruising are the finest lobsters in the world. You have only to sink a few cages every night when at anchor; you will draw them up full in the morning, and place them in a well in your hold. As soon as you have enough to make a paying voyage, round you will run to Greenock, where is always a ready market and good prices.”

Here Ralph jumped up and rubbed his hands; and Rory, forgetting his bruised shoulder and still bandaged head, hopped off the sofa to cry “Hurrah!” and this made Kooran bark, and of course Bran chimed in for company’s sake, and McBain wagged his beard and laughed with delight at the pleasure his suggestion seemed to afford the three young men; and, indeed, for the time being he felt quite as youthful as either of them.

“And I’ll be the crew of the craft,” said McBain. “Allan ought to be captain, and you others naval cadets.”

“Yes,” said Rory, “that will suit us excellently, and we can take lessons from you and Allan in seamanship, and by-and-bye be just as clever sailors as either of you.”

“Ay, that you can,” said McBain.

Allan laid his hand on Ralph’s shoulder, for the latter was gazing quietly and dreamily firewards.

“What are you thinking about?” said Allan.

Ralph smiled as he made reply.

“I was thinking,” he said, “that our adventures as amateur yachtsmen will not begin and end with cruising among the Western Isles of Scotland, pleasant and romantic enough though that may be. Listen to me, boys. It has been the one dream of my life to be able to be master of a beautiful yacht, and to sail away to far countries, and to see the world in earnest. Now I know I shall have an opportunity of doing so. My good, kind old father will baulk me in nothing that is reasonable; and if, after a few months’ cruising in this boat, I can convince him that I have mastered the rudiments of seamanship, he will, I believe, let me have a real yacht, capable of voyaging to any part of the world!”

“Ah! that would indeed be glorious, boys,” cried Rory, with enthusiasm.

“If we could only arrange it,” said Allan, “so as to all go together.”

“Of course,” said Ralph; “there would not be half the pleasure else. And we would sail to some country, if possible, where Englishmen had never been, or never lived before.”

“To the countries and islands around the Pole, for example,” suggested McBain.

“Yes,” Ralph said; “from all I have read of the Sea of Ice, it seems to me the most fascinating place in the world.”

“Ay,” said McBain; “to me it possesses a strange charm; for everything connected with the countries and seas beyond the Arctic circle is as different from anything one sees elsewhere as though it belonged to some other planet.”

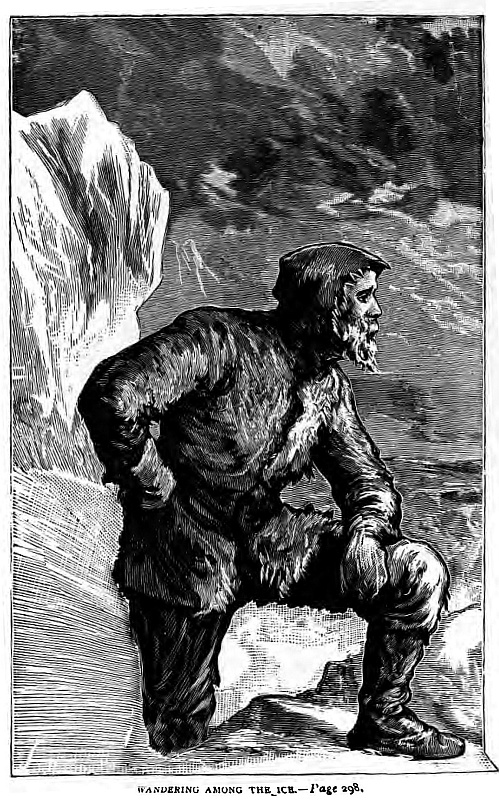

For hours before retiring to rest they talked about Greenland; and McBain told them of many a wild adventure in which he himself had been the principal hero. And among other things he told them of the mammoth caves of Alba Isle, where an untold wealth of ivory lay buried.

For hours after they had retired Allan lay awake, thinking only of that buried treasure. Then he slept, and dreamt he had returned from the far north a wealthy man—that Arrandoon was re-furnished and re-roofed, that he had regained all the proud acres which his fathers had squandered, and that his dear mother and sister were reinstated in the rank of life they were born to adorn, and which was the right of birth of the chiefs of Glentroom.

Do dreams ever come true? At times.

Chapter Four.

The “Flower of Arrandoon”—Old Ap’s Cottage—Trial Trips and Useful Lessons.

I do not think that, during any period of his former life, Allan McGregor’s foster-father was much happier than he was while engaged, with the help of his boy friends, in getting the cutter they had bought ready for her summer cruise among the Western Islands.

They were not quite unassisted in their labours though; no, for had they not the advantage of possessing skilled labour? Was not Tom Ap Ewen their right-hand man; to guide, direct, and counsel them in every difficulty? And right useful they found him, too.

Thomas was a Welshman, as his name indicates; he had been a boatbuilder all his life. He lived in a little house by the lake-side, and this house of his bore in every respect a very strong resemblance to a boat turned upside down. All its furniture and fittings looked as though at one time they had been down to the sea in ships, and very likely they had. Tom’s bed was a canvas cot which might have been white at one time, but which was terribly smoke-begrimed now; Tom’s cooking apparatus was a stove, and, saving a sea-chest which served the double purpose of dais and tool-box, all the seats in his cottage were lockers, while the old lamp that hung from the blackened rafters gave evidence of having seen better days, having in fact dangled from the cabin deck of some trusty yacht.

Tom himself was quite in keeping with his little home. A man of small stature was Tom. I will not call him dapper, because you know that would imply neatness and activity, and there was very little of either about Tom. But he had plenty of breadth of beam, and so stiff was he, apparently, that he looked as if he had been made out of an old bowsprit, and had acted for years in the capacity of figure-head to an old seventy-four. Seen from the front, Tom appeared, on week-days, to be all apron from his chin to his toes; his hard wiry face was bestubbled over in half its length with grey hairs, for Tom found the scissors more handy and far less dangerous than a razor; and, jauntily cocked a little on one side of his head, he wore a square paper cap over a reddish-brown wig. Well, if to this you add a pair of short arms, a pair of hard horny hands, and place two roguish beads of hazel eyes in under his bushy eyebrows, you have just as complete a description of Thomas Ap Ewen as I am capable of giving.

This wee wee man generally went by the name of Old Ap. Of course there were ill-natured people who sometimes, behind Tom’s back, added an e to the Ap; but, honestly speaking, there was not a bit of the ape about him, except, perhaps, when taking snuff. Granting that his partiality for snuff was a fault, it was one that you could reasonably strive to forgive, in consideration of his many other sterling qualities.

Well, Tom was master of the yard, so to speak, into which the purchased cutter was hauled to be fitted, and although McBain did not take all the advice that was tendered to him, it is but fair to say that he benefited by a good deal of it.

It would have done the heart of any one, save a churl, good to have seen how willingly those boys worked; axe, or saw, or hammer, plane or spokeshave, nothing came amiss to them. Allan was undoubtedly the best artisan; he had been used to such work before; but generally where there’s a will there’s a way, and the very newness of the idea of labouring like ordinary mechanics lent, as far as Ralph and Rory were concerned, a charm to the whole business.

“There is nothing hackneyed about this sort of thing, is there?” Ralph would say, looking up from planing a deck-spar.

“There is a deal to learn, too,” Rory might answer. “Artisans mustn’t be fools, sure. But how stiff my saw goes!”

“A bit of grease will put that to rights.” Ralph’s face would beam while giving a bit of information like this, or while initiating Rory into the mysteries of dovetailing, or explaining to him that when driving a nail he must hit it quietly on the head, and then it would not go doubling round his finger.

Old Ap and McBain were both of them very learned—or they appeared to be so—in the subject of rigging, nor did their opinions in this matter altogether coincide. Old Ap’s cottage and the yard were quite two miles—Scotch ones—from the castle, so on the days when they were busy our heroes would not hear of returning to lunch.

“Isn’t good bread and cheese, washed down with goat’s milk, sufficient for us?” Ralph might say.

And Rory would reply, “Yes, my boy, indeed, it’s food fit for a king.”

After luncheon was the time for a little well-earned rest. The young men would stroll down towards the lake, by whose banks there was always something to be seen or done for half-an-hour, if it were only skipping flat stones across its surface; while the two elder ones would enjoy the dolce far niente and their odium cum dignitate seated on a log.

“Well,” said old Ap, one day, “I suppose she is to be cutter-rigged, though for my own part I’d prefer a yawl.”

“There is no accounting for tastes,” replied McBain; “and as to me, I don’t care for two masts where one will do. She won’t be over large, you know, when all is said and done.”

“Just look you,” continued Ap, “how handy a bit of mizen is.”

“It is at times, I grant you,” replied McBain.

“To be sure,” said Ap, “you may sail faster with the cutter rig, but then you don’t want to race, do you, look see?”

“Not positively to race, Mr Ewen,” replied McBain, “but there will be times when it may be necessary to get into harbour or up a loch with all speed, and if that isn’t racing, why it’s the very next thing to it.”

“Yes, yes,” said old Ap, “but still a yawl is easier worked, and as you’ll be a bit short-handed—”

“What!” cried McBain, in some astonishment; “an eight-ton cutter, and four of us. Call you that short-handed?”

“Yes, yes, I do, look see,” answered Ap, taking a big pinch of his favourite dust, “because I’d call it only two; surely you wouldn’t count upon the Englishmen in a sea-way.”

McBain laughed.

“Why,” he said, “before a month is over I’ll have those two Saxon lads as clever cuttersmen as ever handled tiller or belayed a halyard. Just wait until we return up the loch after our summer’s cruise, and you can criticise us as much as ever you please.”

Now these amateur yacht-builders, if so we may call them, took the greatest of pains, not only with the decking and rigging of their cutter, but with her painting and ornamentation as well. There were two or three months before them, because they did not mean to start cruising before May, so they worked away at her with the plodding steadiness of five old beavers. In their little cabin, where it must be confessed there was not too much head room, there was nevertheless a good deal of comfort, and all the painting and gilding was done by Rory’s five artistic fingers. In fact, he painted her outside and in, and he named her the Flower of Arrandoon, and he painted that too on her stern, with a great many dashes and flourishes, that any one, save himself, would have deemed quite unnecessary.

It was only natural that they should do their best to make their pigmy vessel look as neat and as nice as possible; but they had another object in view in doing so, for as soon as their summer cruise was over they meant to sell her. So that what they spent upon her would not really be money thrown to the winds, but quite the reverse. Young Ralph knew dozens of young men just as fond of sailing and adventure as he was, and he thought it would be strange indeed if he himself, assisted by the voluble Rory, could not manage to give such a glowing account of their cruise, and of all the fun and adventures they were sure to have, as would make the purchase of the Flower of Arrandoon something to be positively competed for.

When she was at last finished and fitted, and lying at anchor, in the creek of Glentroom, with the water lap-lapping under her bows, her sails all nicely clewed, and her slender topmast bobbing and bending to the trees, as if saluting them, why I can assure you she looked very pretty indeed. But there was something more than mere prettiness about her; she looked useful. Care had been taken with her ballasting, so she rode like a duck in the water. She had, too, sufficient breadth of beam, and yet possessed depth of keel enough to make her safe in a sea-way, and McBain knew well—and so, for that matter, did Allan—that these were solid advantages in the kind of waters that would form their cruising ground. In a word, the Flower of Arrandoon was a comfortable sea-worthy boat, well proportioned and handy, and what more could any one wish for?

And now the snow had all fled from the hills and the glens, only on the crevices of mountain tops was it still to be seen—ay, and would be likely to be seen all the summer through, but softly and balmily blew the western winds, and the mavis and blackbird returned to make joyous music from morning’s dawn till dewy eve. Half hidden in bushy dells, canary-coloured primroses smiled over the green of their leaves, and ferns and breckans began to unfold their brown fingers in the breeze, while buds on the silvery-scented birches that grew on the brae-lands, and verdant crimson-tipped tassels on the larches that courted the haughs, told that spring had come, and summer itself was not far distant.

And so one fine morning says McBain, “Now, Allan, if your friends are ready, we’ll go down to the creek, get up our bit of an anchor, and be off on a trial trip.”

Trial trips are often failures, but that of the boys’ cutter certainly was not. Everything was done under McBain’s directions, Allan doing nearly all the principal work, though assisted by old Ap; but if Ralph and Rory did not work, they watched. Nothing escaped them, and if they did not say much, it was because, like Paddy’s parrot, they were “rattling up the thinking.”

The day was beautiful—a blue sky with drifting cloudlets of white overhead, and a good though not stiff breeze blowing right up the loch; so they took advantage of this, and scudded on for ten miles to Glen Mora. They did not run right up against the old black pier, and smash their own bowsprit in the attempt to knock it down. No, the boat was well steered, and the sails lowered just at the right time, the mainsail neatly and smartly furled, and covered as neatly, and the jib stowed. Old Ap was left as watchman, and McBain and his friends went on shore for a walk and luncheon.

In the evening, after they had enjoyed to the full their “bit of a cruise on shore,” as McBain called it, they returned to their boat, and almost immediately started back for Glentroom. The wind still blew up the loch; it was almost, though not quite, ahead of them. This our young yachtsmen did not regret, for, as their sailing-master told them, it would enable them to find out what the cutter could do, for, tacking and half-tacking, they had to work to windward.

It was gloaming ere they dropped anchor again in the creek, and McBain’s verdict on the Flower of Arrandoon was a perfectly satisfactory one.

“She’ll do, gentlemen,” he said, “she’ll do; she is handy, and stout, and willing. There is no extra sauciness about her, though she is on excellent terms with herself, and although she doesn’t sail impudently close to the wind, still I say she behaves herself gallantly and well.”

It wanted nothing more than this to give Allan and his friends an appetite for the haunch of mountain mutton that awaited them on their return to the castle. They were in bounding spirits too; it made every one else happy just to see them happy, so that everything passed off that night as merrily as marriage bells.

The loch near the old Castle of Arrandoon is one of the great chain of lakes that stretch from east to west of Scotland, and are joined together by a broad and deep canal, which gives passage to many a stately ship. This canal, once upon a time, was looked upon as one of the engineering wonders of the world, leading as it does often up and over hills so high and wild that in sober England they would be honoured with the title of mountains.

For a whole week or more, ere the cutter turned her bows to the southward and west, and started away on her summer cruise, almost every day was spent on this loch. It is big enough in all conscience for manoeuvres of any kind, being in many places betwixt two and three miles in width, while its length is over twenty.

It might be said, with a good deal of truth, that Allan McGregor had spent his life in boats upon lakes, for as soon as his little hand was big enough to grasp a tiller he had held one. He knew all about boats and boat-sailing, and was, on the whole, an excellent fresh-water sailor. With Ralph and Rory it was somewhat different, good oarsman though the former at all events was. However, they were apt pupils, and, with good health and willingness to work, what is it a boy will not learn?

In old Ap’s cottage were models of several well-rigged vessels of the smaller class, the principal of them being a sloop, a cutter, and a yawl. Ap delighted to give lectures on the peculiar merits and rigging of these, interspersed with many a “Yes, yes, young shentlemen, and look you see,” spoken with the curious accent which Welshmen alone can give to such simple words. These models our heroes used to copy, so that, theoretically speaking, they knew a great deal about seamanship before they stepped on board the cutter to take their first cruise.

Practice alone makes perfect in any profession, and although experience is oftentimes a hard and cruel teacher, there is no doubt she docet stultos, and her lessons are given with a force there is no forgetting. Of such was the lesson Rory got one morning; he had the tiller in his hand, and was bowling along full before the wind. It seemed such easy work sailing thus, and Rory was giving more of his time than he ought to have done to conversation with his companions, and even occasionally stealing a glance on shore to admire the scenery, when all at once, “Flop! flop! crack! harsh!” cried the sail, and round came the boom. The wind was not very fresh, so there was little harm done; besides, McBain was there, and I verily believe that had that old tar gone to sleep, he would have been dozing in dog fashion with his weather eye open. But on this occasion poor Rory was scratching and rubbing a bare head.

“Crack, harsh!” he said, looking at the offending sail; “troth and indeed it is harsh you crack, I can tell you.”

“Ah!” said McBain, quietly, “sailing a bit off, you see.”

“’Deed and indeed,” replied Rory, “but you’re right, and by the same token my hat’s off too, and troth I thought the poor head of me was in it.”

It will be observed that Rory had a habit of talking slightly Irish at times, but I must do him the credit of saying that he never did so except when excited, or simply “for the fun of the thing.”

Another useful lesson that both Ralph and Rory took some pains to learn was to look out for squalls. They learned this on the loch, for there sometimes, just as you are quietly passing some tree-clad bank or brae, you all at once open out some beautifully romantic glen. Yes, both beautiful and romantic enough, but down that gully sweeps the gusty wind, with force enough often to tear the sticks off the sturdiest boat, or lay her flat and helpless on her beam ends. But the lesson, once learned, was taken to heart, and did them many a good turn in after days, when sailing away over the seas of the far North in their saucy yacht, the Snowbird.

The time now drew rapidly near for them to start away to cruise in earnest. They had spent what they termed “a jolly time of it” in Glentroom. Time had never, never seemed to fly so quickly before. They had had many adventures too; but one they had only a day or two before sailing was the strangest. As, however, this adventure had so funny a beginning, though all too near a fatal ending, I must reserve it for another chapter.

Chapter Five.

Showing how Royalty Visited Arrandoon, and how our Heroes Returned the Call.

The windows of the double-bedded chamber occupied by Allan McGregor’s guests overlooked both lake and glen. At one corner of it was a kind of turret recess; this had been originally used as a dressing-room, but Allan had gone to some trouble and expense in fitting it up as an own, own room for Rory. Ralph called it Rory’s “boudoir,” Rory himself called it his “sulky.” The floor of the curious little room was softly carpeted; the walls were hung with ancient tapestry; the windows neatly draped. There was a little bookcase in it, in which, much to his surprise, the young man found all his favourite poets and authors. His fiddle and music were in this turret as well; so it was all very nice and snug indeed.

Scarcely a day passed that Rory did not spend an hour or two in his “sulky,” generally after luncheon, when not on or at the lake; and even while reclining on his lounge the view that he could catch a glimpse of was just as romantic and beautiful as any boy poet could wish. There was no door between this and the bedchamber, only a curtain which could be drawn at pleasure.

Now, as I happen to love the truth for its own simple sake, I must tell you that neither Rory nor Ralph was very fond of early rising, practically speaking—theory being another thing. Allan was often away at the river hours and hours before breakfast, and the beautiful dishes of mountain trout that lay on the table, so crisp and still, had been frisking and gambolling only a short time before in their native streams. But Allan’s friends—well, it may have been the Highland air, you know, which is remarkably strong and pure, but anyhow, neither of them thought of stirring until the first gong pealed its thunders forth. It was not that they did not get a good example set them by the sun, for, it being now the month of May, that luminary deemed it his duty to get up himself, and to arouse most ordinary mortals, shortly after four o’clock.

The list of ordinary mortals, so far as the castle was concerned, included old Janet the cook, and most of the other servants and retainers, and all the dogs, and all the cocks and hens, and ducks and geese, and turkeys, to say nothing of pigs and pigeons, sheep and cattle; and as every single mortal among them felt himself bound as soon as his eyes were open to express his feelings audibly, and in his own peculiar fashion, you can easily believe that the din and the hubbub around Arrandoon at early morning were something considerable. Whether asleep or awake, Ralph had an easy mind, nothing bothered him. I believe he could have slept throughout general quarters at sea, with cannon thundering overhead, if he had a mind to; but with Rory it was somewhat different, and the cock-crowing used to fidget him in his dreams. If there had been only one cock, and that cock had crowed till his comb fell off, it would have been merely monotonous, and Rory would have slumbered on in peace, but there were so many cocks of so many strains. The game-cocks crowed boldly and bravely, and their tones clearly proved them kings of the harem; the bantams shrieked defiance at every other cock about the place, but no cock about the place took any heed of them; the cowardly Shanghais kept at a safe distance from the game-birds, and shouted themselves hoarse; and besides these there was the half-apologetic, half-formed crow of the cockerels, who got thrashed a dozen times everyday because they dared to mimic their betters.

These sounds, I say, fidgeted our poetic Rory; but when half a dozen fantail pigeons would alight outside the window, and strut about and cry, “Coo, coo, troubled with you, troubled with you,” then Rory would become more sensible, and he would open one eye to have a look at the clock on the mantelpiece. Mind you, he wouldn’t open both eyes for the world, lest he should awaken altogether.

“Oh!” he would think to himself, “only five o’clock; gong won’t go for three hours yet. How jolly!”

Then he would turn round on the other side and go to sleep again. The cocks might go on crowing, and the pigeons might preen their feathers and “coo-coo” as much as they pleased now. Rory heard no more until “Ur-ur—R-Rise, Ur-ur—R-Ralph and Rory,” roared the gong.

One particular morning Rory had opened his one eye just as usual, had his look at the clock, had rejoiced that it was still early, and had turned himself round to go off once more to the land of Nod, when, suddenly, there arose from beneath such an inexpressible row, such an indefinable din, as surely never before had been heard around the Castle of Arrandoon. The horses stamped and neighed in their stables, the cattle moaned a double bass, the pigs squeaked a shrill tenor, the fowl all went mad.

“Whack, whack, whack!” roared the ducks.

“Kank, kank, kank?” cried the geese.

“Hubbub—ub—ub—bub!” yelled the turkeys.

Rory sat bolt upright in bed, with both eyes open, more fully awake than ever he had felt in his life before.

“Hubbub, indeed!” says Rory; “indeed, then, I never heard such a hubbub before in all my born days. Ralph, old man, Ralph. Sit up, my boy. I wonder what the matter can be.”

“And so do I,” replied Ralph, without, however, offering to stir; “but surely a fellow can wonder well enough without getting out of bed to wonder.”

“Ooh! you lazy old horse!” cried Rory; “well, then, it’s myself that’ll get up.”

Suiting the action to the word, Rory sprang out of bed, and next moment he had thrown open his “sulky” window and popped his head and shoulders out. He speedily drew them in again and called to Ralph, and the words he used were enough to bring even that matter-of-fact hero to his side with all the speed he cared to expend.

What they saw I’ll try to explain to you.