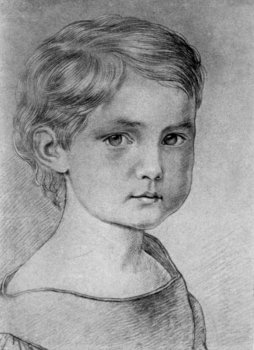

F. Max Müller

Aged 4.

BY THE

Rt. Hon. Professor F. MAX MÜLLER, K.M.

WITH PORTRAITS

New York

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1901

Copyright, 1901, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

For some years past my father had, in the intervals of more serious work, occupied his leisure moments in jotting down reminiscences of his early life. In 1898 and 1899 he issued the two volumes of Auld Lang Syne, which contained recollections of his friends, but very little about his own life and career. In the Introductory Chapter to the Autobiography he explains fully the reasons which led him, at his advanced age, to undertake the task of writing his own Life, and he began, but alas! too late, to gather together the fragments that he had written at different times. But even during the last two years of his life, and after the first attack of the illness which finally proved fatal, he would not devote himself entirely to what he considered mere recreation, as can be seen from such a work as his Six Systems of Indian Philosophy published in May, 1889, and from the numerous articles which continued to appear up to the very time of his death.

During the last weeks of his life, when we all knew that the end could not be far off, the Autobiography[vi] was constantly in his thoughts, and his great desire was to leave as much as possible ready for publication. Even when he was lying in bed far too weak to sit up in a chair, he continued to work at the manuscript with me. I would read portions aloud to him, and he would suggest alterations and dictate additions. I see that we were actually at work on this up to the 19th of October, and on the 28th he was taken to his well-earned rest. One of the last letters that I read to him was a letter from Messrs. Longmans, his lifelong publishers, urging the publication of the fragments of the Autobiography that he had then written.

My father’s object in writing his Autobiography was twofold: firstly, to show what he considered to have been his mission in life, to lay bare the thread that connected all his labours; and secondly, to encourage young struggling scholars by letting them see how it had been possible for one of themselves, without fortune, a stranger in a strange land, to arrive at the position to which he attained, without ever sacrificing his independence, or abandoning the unprofitable and not very popular subjects to which he had determined to devote his life.

Unfortunately the last chapter takes us but little beyond the threshold of his career. There is enough, however, to enable us to see how from his earliest student days his leanings were philosophical and religious rather than classical; how the study of Herbart’s philosophy encouraged him in the[vii] work in which he was engaged as a mere student, the Science of Language and Etymology; how his desire to know something special, that no other philosopher would know, led him to explore the virgin fields of Oriental literature and religions. With this motive he began the study of Arabic, Persian, and finally Sanskrit, devoting himself more especially to the latter under Brockhaus and Rückert, and subsequently under Burnouf, who persuaded him to undertake the colossal work of editing the Rig-veda.

The Autobiography breaks off before the end of the period during which he devoted himself exclusively to Sanskrit. It is idle to speculate what course his life’s work might have taken, had he been elected to the Boden Professorship of Sanskrit; but he lived long enough to realize that his rejection for that chair in 1860, which was so hard to bear at the time, was really a blessing in disguise, as it enabled him to turn his attention to more general subjects, and devote himself to those philological, philosophical, religious and mythological studies, which found their expression in a series of works commencing with his Lectures on the Science of Language, 1861, and terminating with his Contributions to the Science of Mythology, 1897,—“the thread that connects the origin of thought and language with the origin of mythology and religion.”

As to his advice to struggling scholars, the self-depreciation,[viii] which, as Professor Jowett said, is one of the greatest dangers of an autobiography, makes my father rather conceal the real causes of his success in life. He even goes so far as to say, “everything in my career came about most naturally, not by my own effort, but owing to those circumstances or to that environment, of which we have heard so much of late”: or again, “it was really my friends who did everything for me and helped me over many a stile and many a ditch.” No doubt in one sense this is true, but not in the sense in which it would have been true had he, when at the University, accepted the offer which he tells us a wealthy cousin made him, to adopt him and send him into the Austrian diplomatic service, and even to procure him a wife and a title into the bargain. The friends who helped him, men such as Humboldt, Burnouf, Bunsen, Stanley, Kingsley, Liddell, to mention only a few, were men whose very friendship was the surest proof of my father’s merits. The real secret of his success lay not in his friends, but in himself;—in the knowledge that his success or failure in life depended entirely on his own efforts; in the fixity of purpose which made him refuse all offers that would lead him from the pathway that he had laid down for himself; and in the unflagging industry with which he strove to reach the goal of his ambition. “My very struggles,” he writes, “were certainly a help to me.”

When I came to examine the manuscript with[ix] a view to sending it to press, I found that there was a good deal of work necessary before it could be published in book form. The fragments were in many cases incomplete; there was no division into chapters, no connexion between the various periods and episodes of his life; important incidents were omitted; while, owing to the intermittent way in which he had been writing, there were frequent repetitions. My father was always most critical of his own style, and would often, when correcting his proof-sheets, alter a whole page, because a word or a phrase displeased him, or because some new idea, some happier mode of expression, occurred to him; but in the case of his Autobiography, the only revision that he was able to give, was on his deathbed, while I read the manuscript aloud to him.

My father points out how rarely the sons of great musicians or great painters become distinguished in the same line themselves. “It seems,” he says, “almost as if the artistic talent were exhausted by one generation or one individual”; and I fear that, in my case at all events, the same remark applies to literary talent. I have done my best to string the fragments together into one connected whole, only making such insertions, elisions and alterations as appeared strictly necessary. Any deficiency in literary style that may be noticeable in portions of the book should be ascribed to the inexperience of the editor.

I have thought it right to insert the last chapter,[x] which I call “A Confession,” though I am not sure that my father intended it to be included in his Autobiography. It will, however, explain the attitude which he observed throughout his life, in keeping aloof, as far as possible, from the arena of academic contention at Oxford. He was never chosen a member of the Hebdomadal Council, he rarely attended meetings of Convocation or Congregation; he felt that other people, with more leisure at their disposal, could be of more use there; but he never refused to work for his University, when he felt that he was able to render good service, and he acted for years as a Curator of the Bodleian Library and of the Taylorian Institute, and as a Delegate of the Clarendon Press.

With reference to the illustrations, it may be of interest to readers to know that the portraits of my grandfather and grandmother are taken from pencil-drawings by Adolf Hensel, the husband of Mendelssohn’s sister Fanny, herself a great musician, who, as my father tells us in Auld Lang Syne, really composed several of the airs that Mendelssohn published as his Songs without Words. The last portrait of my father is from a photograph taken soon after his arrival in Oxford by his great friend Thomson, afterwards Archbishop of York.

Nothing now remains for me but to acknowledge the debt that I owe personally to this book. “Work,” my father used often to say to me, “is the best healer of sorrow. In grief or disappointment,[xi] try hard work; it will not fail you.” And certainly during these three sad months, I have proved the truth of this saying. He could not have left me a surer comfort or more welcome distraction than the duty of preparing for press these pages, the last fruits of that mind which remained active and fertile to the last.

W. G. MAX MÜLLER.

Oxford, January, 1901.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | Childhood at Dessau | 46 |

| III. | School-days at Leipzig | 97 |

| IV. | University | 115 |

| V. | Paris | 162 |

| VI. | Arrival in England | 188 |

| VII. | Early Days at Oxford | 218 |

| VIII. | Early Friends at Oxford | 272 |

| IX. | A Confession | 308 |

| INDEX | 319 | |

| F. Max Müller, Aged Four | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| My Father | 46 |

| My Mother | 58 |

| F. Max Müller, Aged Fourteen | 106 |

| "" Aged Twenty | 156 |

| "" Aged Thirty | 268 |

After the publication of the second volume of my Auld Lang Syne, 1899, I had a good deal of correspondence, of public criticism, and of private communings also with myself, whether I should continue my biographical records in the form hitherto adopted, or give a more personal character to my recollections. Some of my friends were evidently dissatisfied. “The recollections of your friends and the account of the influence they exercised on you,” they said, “are interesting, no doubt, as far as they go, but we want more. We want to know the springs, the aspirations, the struggles, the failures, and achievements of your life. We want to know how you yourself look at yourself and at your past life and its various incidents.” What they really wanted was, in fact, an autobiography. “No one,” as a friend of mine, not an Irishman, said, “could do that so well as yourself, and you will never escape a biographer.” I confess that did not frighten me very much. I[2] did not think the danger of a biography very imminent. Besides, I had already revised two biographies and several biographical notices even during my lifetime. No sensible man ought to care about posthumous praise or posthumous blame. Enough for the day is the evil thereof. Our contemporaries are our right judges, our peers have to give their votes in the great academies and learned societies, and if they on the whole are not dissatisfied with the little we have done, often under far greater difficulties than the world was aware of, why should we care for the distant future? Who was a greater giant in philosophy than Hegel? Who towered higher than Darwin in natural science? Yet in one of the best German reviews[1] the following words of a young German biologist[2] are quoted, and not without a certain approval: “Darwinism belongs now to history, like that other curiosum of our century, the Hegelian philosophy. Both are variations on the theme, How can a generation be led by the nose? and they are not calculated to raise our departing century in the eyes of later generations.”

If I was afraid of anything, it was not so much the severity of future judges, as the extreme kindness and leniency which distinguish most biographies in our days. It is true, it would not be easy for those who have hereafter to report on our labours [3]to discover the red thread that runs through all of them from our first stammerings to our latest murmurings. It might be said that in my own case the thread that connects all my labours is very visible, namely, the thread that connects the origin of thought and languages with the origin of mythology and religion. Everything I have done was, no doubt, subordinate to these four great problems, but to lay bare the connecting links between what I have written and what I wanted to write and never found time to write, is by no means easy, not even for the author himself. Besides, what author has ever said the last word he wanted to say, and who has not had to close his eyes before he could write Finis to his work? There are many things still which I should like to say, but I am getting tired, and others will say them much better than I could, and will no doubt carry on the work where I had to leave it unfinished. We owe much to others, and we have to leave much to others. For throwing light on such points an autobiography is, no doubt, better adapted than any biography written by a stranger, if only we can at the same time completely forget that the man who is described is the same as the man who describes.

“Friends,” as Professor Jowett said, “always think it necessary (except Boswell, that great genius) to tell lies about their deceased friend; they leave out all his faults lest the public should exaggerate them. But we want to know his faults,—that[4] is probably the most interesting part of him.”

Jowett knew quite well, and he did not hesitate to say so, that to do much good in this world, you must be a very able and honest man, thinking of nothing else day and night; and he adds, “you must also be a considerable piece of a rogue, having many reticences and concealments; and I believe a good sort of roguery is never to say a word against anybody, however much they may deserve it.”

Now Professor Jowett has certainly done some good work at Oxford, but if any one were to say that he also was a considerable piece of a rogue, what an outcry there would be among the sons of Balliol. Jowett thought that the only chance of a good biography was for a man to write memoirs of himself, and what a pity that he did not do so in his own case. His friends, however, who had to write his Life were wise, and he escaped what of late has happened to several eminent men. He escaped the testimonials for this, and testimonials for another life, such as they are often published in our days.

Testimonials are bad enough in this life, when we have to select one out of many candidates as best fitted for an office, and it is but natural that the electors will hardly ever look at them, but will try to get their information through some other channel. But what are called post obit testimonials really go beyond everything yet known in funeral panegyrics. Of course, as no one is asked for such[5] testimonials except those who are known to have been friends of the departed, these testimonials hardly ever contain one word of blame. One feels ashamed to write such testimonials, but if you are asked, what can you do without giving offence? We are placed altogether in a false position. Let any one try to speak the truth and nothing but the truth, and he will find that it is almost impossible to put down anything that in the slightest way might seem to reflect on the departed. The mention of the most innocent failings in an obituary notice is sure to offend somebody, the widow or the children, or some dear friend. I thought that my Recollections had hitherto contained nothing that could possibly offend anybody, nothing that could not have been published during the lifetime of the man to whom it referred. But no; I had ever so many complaints, and I gladly left out, in later editions, names which in many cases were really of no consequence compared with what they said and did.

Surely every man has his faults and his little and often ridiculous weaknesses, and these weaknesses belong quite as much to a man’s character as his strength; nay, with the suppression of the former the latter would often become almost unintelligible.

I like the biographies of such friends of mine as Dean Stanley, Charles Kingsley, and Baron Bunsen. But even these are deficient in those shadows which would but help to bring out all the more clearly[6] the bright points in their character. We should remember the words of Dr. Wendell Holmes: “We all want to draw perfect ideals, and all the coin that comes from Nature’s mint is more or less clipped, filed, ‘sweated,’ or bruised, and bent and worn, even if it was pure metal when stamped, which is more than we can claim, I suppose, for anything human.” True, very true; and what would the departed himself say to such biographies as are now but too common,—most flattering pictures no doubt, but pictures without one spot or wrinkle? In Germany it was formerly not an uncommon thing for the author of a book to write a self-review (Selbst-Kritik), and these were generally far better than reviews written by friends or enemies. For who knows the strong and weak points of a book so well as the author? True; but a whole life is more difficult to review and to criticize than a single book. Nevertheless it must be admitted that an autobiography has many advantages, and it might be well if every man of note, nay, every man who has something to say for himself that he wishes posterity to know, should say it himself. This would in time form a wonderful archive for psychological study. Something of the kind has been done already at Berlin in preserving private correspondences. Of course it is difficult to keep such archives within reasonable limits, but here again I am not afraid of self-laudation so much as of self-depreciation.

Professor Jowett, who did not write his own biography,[7] was quite right in saying that there is great danger of an autobiography being rather self-depreciatory; there is certainly something so nauseous in self-praise that most people would shrink far more from self-praise than from self-blame. There may be some kind of subtle self-admiration even in the fault-finding of an outspoken autobiographer; but who can dive into those deepest depths of the human soul? To me it seems that if an honest man takes himself by the neck, and shakes himself, he can do it far better than anybody else, and the castigation, if well deserved, comes certainly with a far better grace from himself than if administered by others.

Few men, I believe, know their real goodness and greatness. Some of the most handsome women, so we are assured, pass through life without ever knowing from their looking-glass that they are handsome. And it is certainly true that men, from sad experience, know their weak points far better than their good points, which they look on as no more than natural.

The Autos, for instance, described by John Stuart Mill, has no cause to be grateful to the Autos that wrote his biography. Mill had been threatened by several future biographers, and he therefore wrote the short biographical account of himself almost in self-defence. But besides the truly miraculous, and, if related by anybody else, hardly credible achievements of his early boyhood and youth, his[8] great achievements in later life, the influence which he exercised both by his writings and still more by his personal and public character, would have found a far more eloquent and truthful interpreter in a stranger than in Mill himself. I remember another case where a most distinguished author tried to escape the oil and the blessings, perhaps the opposite also, from the hands of his future biographers. Froude destroyed the whole of his correspondence, and he wished particularly that all letters written to him in the fullest confidence should be burnt,—and they were. I think it was a pity, for I know what valuable letters were destroyed in that auto da fé; and yet when he had done all this, he seems to have been seized with fear, and just before he returned to Oxford as Regius Professor of Modern History he began to write a sketch of his own life, which was found among his papers. Interesting it certainly was, but fortunately his best friends prevented its publication. It would have added nothing to what we know of him in his writings, and would never have put his real merits in their proper light. Besides, it came to an end with his youth and told us little of his real life.

I flattered myself that I had found the true way out of all these difficulties, by writing not exactly my own life, but recollections of my friends and acquaintances who had influenced me most, and guided me in my not always easy passage through life. As in describing the course of a river, we cannot[9] do better than to describe the shores which hem in and divert the river and are reflected on its waves, I thought that by describing my environment, my friends, and fellow workers, I could best describe the course of my own life. I hoped also that in this way I myself could keep as much as possible in the background, and yet in describing the wooded or rocky shores with their herds, their cottages, and churches, describe their reflected image on the passing river.

But now I am asked to give a much fuller account of myself, not only of what I have seen, but also of what I have been, what were the objects or ideals of my life, how far I have succeeded in carrying them out, and, as I said, how often I have failed to accomplish what I had sketched out as my task in life. People wished to know how a boy, born and educated in a small and almost unknown town in the centre of Germany, should have come to England, should have been chosen there to edit the oldest book of the world, the Veda of the Brahmans, never published before, whether in India or in Europe, should have passed the best part of his life as a professor in the most famous and, as it was thought, the most exclusive University in England, and should actually have ended his days as a Member of Her Majesty’s most honourable Privy Council. I confess myself it seems a very strange career, yet everything came about most naturally, not by my own effort, but owing again to those circumstances[10] or to that environment of which we have heard so much of late.

Young, struggling men also have written to me, and asked me how I managed to keep my head above water in that keen struggle for life that is always going on in the whirlpool of the learned world of England. They knew, for I had never made any secret of it, how poor I was in worldly goods, and how, as I said at Glasgow, I had nothing to depend on after I left the University, but those fingers with which I still hold my pen and write so badly that I can hardly read my manuscript myself. When I arrived I had no family connections in England, nor any influential friends, “and yet,” I was told, “in a foreign country, you managed to reach the top of your profession. Tell us how you did it; and how you preserved at the same time your independence and never forsook the not very popular subjects, such as language, mythology, religion, and philosophy, on which you continued to write to the very end of your life.”

I generally said that most of these questions could best be answered from my books, but they replied that few people had time to read all I had written, and many would feel grateful for a thread to lead them through this labyrinth of books, essays, and pamphlets, which have issued from my workshop during the last fifty years.[3]

All I could say was that each man must find his own way in life, but if there was any secret about my success, it was simply due to the fact that I had perfect faith, and went on never doubting even when everything looked grey and black about me. I felt convinced that what I cared for, and what I thought worthy of a whole life of hard work, must in the end be recognized by others also as of value, and as worthy of a certain support from the public. Had not Layard gained a hearing for Assyrian bulls? Did not Darwin induce the world to take an interest in Worms, and in the Fertilization of Orchids? And should the oldest book and the oldest thoughts of the Aryan world remain despised and neglected?

For many years I never thought of appointments or of getting on in the world in a pecuniary sense. My friends often laughed at me, and when I think of it now, I confess I must have seemed very Quixotic to many of those who tried for this and that, got lucrative appointments, married rich wives, became judges and bishops, ambassadors and ministers, and could hardly understand what I was driving at with my Sanskrit manuscripts, my proof-sheets and revises. Perhaps I did not know myself. Still I was not quite so foolish as they imagined. True, I declined several offers made to me which seemed very advantageous in a worldly sense, but would have separated me entirely from my favourite work.[12]

When at last a professorship of Modern Literature was offered me at Oxford, I made up my mind, though it was not exactly what I should have liked, to give up half of my time to studies required by this professorship, keeping half of my time for the Veda and for Sanskrit in general. This was not so bad after all. People often laughed at me for being professor of the most modern languages, and giving so much of my time and labour to the most ancient language and literature in the world. Perhaps it was not quite right my giving up so much of my time to modern languages, a subject so remote from my work in life, but it was a concession which I could make with a good conscience, having always held that language was one and indivisible, and that there never had been a break between Sanskrit, Latin, and French, or Sanskrit, Gothic, and German. One of my first lectures at Oxford was “On the antiquity of modern languages,” so that I gave full notice to the University as to how I meant to treat my subject, and on the whole the University seems to have been satisfied with my professorial work, so that when afterwards for very good reasons, whether financial, theological, or national, I, or rather my friends, failed to secure a majority in Convocation for a professorship of Sanskrit, the University actually founded for me a Professorship of Comparative Philology, an honour of which I had never dreamt, and to secure which I certainly had never taken any steps.[13]

Here is all my secret. At first, as I said, it required faith, but it also required for many years a perfect indifference as to worldly success. And here again in my career as a Sanskrit scholar, mere circumstances were of great importance. They were circumstances which I was glad to accept, but which I could never have created myself. It was surely a mere accident that the Directors of the Old East India Company voted a large sum of money for printing the six large quartos of the Rig-veda of about a thousand pages each. It was at the time when the fate of the Company hung in the balance, and when Bunsen, the Prussian Minister, made himself persona grata by delivering a speech at one of the public dinners in the City, setting forth in eloquent words the undeniable merits of the Old Company and the wonderful work they had achieved. It was likewise a mere accident that I should have become known to Bunsen, and that he should have shown me so much kindness in my literary work. He had himself tried hard to go to India to discover the Rig-veda, nay, to find out whether there was still such a thing as the Veda in India. The same Bunsen, His Excellency Baron Bunsen, the Prussian Minister in London, on his own accord went afterwards to see the Chairman and the Directors of the East India Company, and explained to them what the Rig-veda was, and that it would be a real disgrace if such a work were published in Germany; and they agreed to vote a sum of money[14] such as they had never voted before for any literary undertaking. Though after the mutiny nothing could save them, I had at least the satisfaction of dedicating the first volume of my edition of the Rig-veda to the Chairman and the Directors of the much abused East India Company,—much abused though splendidly defended also by no less a man than John Stuart Mill.

This is what I mean by friends and circumstances, and that is the environment which I wished to describe in my Recollections instead of always dwelling on what I meant to do myself and what I did myself. Small and large things work wonderfully together. It was the change threatening the government of India, and a mighty change it was, that gave me the chance of publishing the Veda, a very small matter as it may seem in the eyes of most people, and yet intended to bring about quite as mighty a change in our views of the ancient people of the world, particularly of their languages and religions. This, too—the development of language and religion—seems of importance to some people who do not care two straws for the East India Company, particularly if it helps us to learn what we really are ourselves, and how we came to be what we are.

In one sense biographies and autobiographies are certainly among the most valuable materials for the historian. Biography, as Heinrich Simon, not Henri Simon, said, is the best kind of history, and[15] the life of one man, if laid open before us with all he thought and all he did, gives us a better insight into the history of his time than any general account of it can possibly do.

Now it is quite true that the life of a quiet scholar has little to do with history, except it may be the history of his own branch of study, which some people consider quite unimportant, while to others it seems all-important. This is as it ought to be, till the universal historian finds the right perspective, and assigns to each branch of study and activity its proper place in the panorama of the progress of mankind towards its ideals. Even a quiet scholar, if he keeps his eyes open, may now and then see something that is of importance to the historian. While I was living in small rooms at Leipzig, or lodging au cinquième in the Rue Royale at Paris, or copying manuscripts in a dark room of the old East India House in Leadenhall Street, I now and then caught glimpses of the mighty stream of history as it was rushing by. At Leipzig I saw much of Robert Blum who was afterwards fusillé at Vienna by Windischgrätz in defiance of all international law, for he was a member of the German Diet, then sitting at Frankfurt. From my windows at Paris I looked over the Boulevard de la Madeleine, and down on the right to the Chambre des Députés, and I saw from my windows the throne of Louis Philippe carried along by its four legs by four women on horseback, with Phrygian caps and red scarfs, and I saw the[16] next morning from the same windows the stretchers carrying the dead and wounded from the Boulevards to a hospital at the back of my street. In my small study at the East India House I saw several of the Directors, Colonel Sykes and others, and heard them discussing the fate of the East India Company and of the vast empire of India too, and at the same time the private interests of those who hoped to be Members of the new India Council, and those who despaired of that distinction. I was the first to bring the news of the French Revolution in February to London, and presented a bullet that had smashed the windows of my room at Paris, to Bunsen, who took it in the evening to Lord Palmerston. After I had seen the Revolution in Paris and the flight of the King and the Duchesse d’Orléans, I was in time to see in London the Chartist Deputation to Parliament, and the assembled police in Trafalgar Square, when Louis Napoleon served as a Special Constable, and I heard the Duke of Wellington explain to Bunsen, that though no soldier was seen in the streets there was artillery hidden under the bridges, and ready to act if wanted. I could add more, but I must not anticipate, and after all, to me all these great events seemed but small compared with a new manuscript of the Veda sent from India, or a better reading of an obscure passage. Diversos diversa iuvant, and it is fortunate that it should be so.

All these things, I thought, should form part of[17] my Recollections, and my own little self should disappear as much as possible. Even the pronoun I should meet the reader but seldom, though in Recollections it was as impossible to leave it out altogether as it would be to take away the lens from a photographic camera. Now I believe I have always been most willing to yield to my friends, and I shall in this matter also yield to them so far that in the Recollections which follow there will be more of my inward and outward struggles; but I must on the whole adhere to my old plan. I could not, if I would, neglect the environment of my life, and the many friends that advised and helped me, and enabled me to achieve the little that I may have achieved in my own line of study.

If my friends had been different from what they were, should I not have become a different man myself, whether for good or for evil? And the same applies to our natural surroundings also. And here I must invoke the patience of my readers, if I try to explain in as few words as possible what I think about environment, and what about heredity or atavism.

I was a thorough Darwinian in ascribing the shaping of my career to environment, though I was always very averse to atavism, of which we have heard so much lately in most biographies. Even with respect to environment, however, I could not go quite so far as certain of our Darwinian friends, who maintain that everything is the result of environment,[18] or translated into biographical language, that everybody is a creature of circumstances. No, I could not go so far as that. Environment may shape our course and may shape us, but there must be something that is shaped, and allows itself to be shaped. I was once seriously asked by one who considers himself a Darwinian whether I did not know that the Mammoth was driven by the extreme cold of the Pleiocene Period to grow a thick fur in his struggle for life. That he grew then a thicker fur, I knew, but that surely does not explain the whole of the Mammoth, with and without a thick fur, before and after the fur. It is really a pity to see for how many of these downright absurdities Darwin is made responsible by the Darwinians. He has clearly shown how in many cases the individual may be modified almost beyond recognition by environment, but the individual must always have been there first. Before we had a spaniel and a Newfoundland dog there must have been some kind of dog, neither so small as the spaniel nor so large as the Newfoundland, and no one would now doubt that these two belonged to the same species and presupposed some kind of a less modified canine creature. It is equally true that every individual man has been modified by his surroundings or environment, if not to the same extent as certain animals, yet very considerably, as in the case of Kaspar Hauser, the man with the iron mask, or the mutineers of the Bounty in the Pitcairn Islands.[19] But there must have been the man first, before he could be so modified. Now it was this very individual, my own self in fact, the spiritual self even more than the physical, that interested my critics, while I thought that the circumstances which moulded that self would be of far greater interest than the self itself. Of course all the modifications that men now undergo are nothing if compared to the early modifications which produced what we speak of as racial, linguistic, or even national peculiarities. That we are English or German, that we are white or black, nay, if you like, that we are human beings at all, all this has modified our self, or our germ-plasm, far more powerfully than anything that can happen to us as individuals now.

When my friends and readers assured me that an account of my early struggles in the battle of life would be useful to many a young, struggling man, all I could say was that here again it was really my friends who did everything for me, and helped me over many a stile, and many a ditch, nay, without whom I should never have done whatever I did for the Sciences of Language, of Mythology, and Religion, in fact for Anthropology in the widest sense of that word. My very struggles were certainly a help to me, even my opponents were most useful to me. The subjects on which I wrote had hardly been touched on in England, at least from the historical point of view which I took, and I had not only to overcome the indifference of the public, but[20] to disarm as much as possible the prejudices often felt, and sometimes expressed also, against anything made in Germany! Now I confess I could never understand such a prejudice among men of science. Was I more right or more wrong because I was born in Germany? Is scientific truth the exclusive property of one nation, of Germany, or of England? If I say two and two make four in German, is that less true because it is said by a German? and if I say, no language without thought, no thought without language, has that anything to do with my native country? The prejudice against strangers and particularly against Germans is, no doubt, much stronger now than it was at the time when I first came to England. I had spent nearly two years in Paris, and there too there existed then so little of unfriendly feeling towards Germany, that one of the best reviews to which the rising scholars and best writers of Paris contributed was actually called Revue Germanique. Who would now venture to publish in Paris such a review and under such a title? If there existed such an anti-German feeling anywhere in England when I arrived here in the year 1846, one would suppose that it existed most strongly at Oxford. And so it did, no doubt, particularly among theologians. With them German meant much the same as unorthodox, and unorthodox was enough at that time to taboo a man at Oxford. In one of the sermons preached in these early days at St. Mary’s, German theologians such[21] as Strauss and Neander (sic) were spoken of as fit only to be drowned in the German Ocean, before they reached the shores of England. I do not add what followed: the story is too well known. I was chiefly amused by the juxtaposition of Strauss and Neander, whose most orthodox lectures on the history of the Christian Church I had attended at Berlin. Neander was certainly to us at Berlin the very pattern of orthodoxy, and people wondered at my attending his lectures. But they were good and honest lectures. He was quite a character, and I feel tempted to go a little out of my way in speaking of him. By birth a Jew, he became one of the most learned Christian divines. Ever so many stories were told of him, some true, some no doubt invented. I saw him often walking to and from the University to give his lectures in a large fur coat, with high black polished boots beneath, but showing occasionally as he walked along. It was told that he once sent for a doctor because he was lame. The doctor on examining his feet, saw that one boot was covered with mud, while the other was perfectly clean. The Professor had walked with one foot on the pavement, with the other in the gutter, and was far too much absorbed in his ideas to discover the true cause of his discomfort. He lived with his sister, who took complete care of him and saw to his wardrobe also. She knew that he wore one pair of trousers, and that on a certain day in the year the tailor brought him a new pair. Great was her[22] amazement when one day, after her brother had gone to the University, she discovered his pair of trousers lying on a chair near his bed. She at once sent a servant to the Professor’s lecture-room to inquire whether he had his trousers on. The hilarity of his class may be imagined. The fact was it was the very day on which the tailor was in the habit of bringing the new pair of trousers, which the Professor had put on, leaving his usual garment behind.

Many more stories of his absent-mindedness were en vogue about Dr. Neander, but that this man, a pillar of strength to the orthodox in Germany, who was looked up to as an infallible Pope, should have his name coupled with that of Strauss certainly gave one a little shock. Yet it was at Oxford that I pitched my tent, chiefly in order to superintend the printing of my Rig-veda at the University Press there, and never dreaming that a fellowship, still less a professorship in that ancient Tory University, would ever be offered to me.

For me to go to Oxford to get a fellowship or professorship would have seemed about as absurd as going to Rome to become a Cardinal or a Pope; and yet in time I was chosen a Fellow of All Souls, and the first married Fellow of the College, and even a professorship was offered to me when I least expected it. The fact is, I never thought of either, and no one was more surprised than myself when I was asked to act as deputy, and then as full Taylorian Professor; no one could have mistrusted his[23] eyes more than I did, when one of the Fellows of All Soul’s informed me by letter that it was the intention of the College to elect me one of its fellows. My ambition had never soared so high. I was thinking of returning to Leipzig as a Privat-docent, to rise afterwards to an extraordinary and, if all went well, to an ordinary professorship.

But after these two appointments at Oxford had secured to me what I thought a fair social and financial position in England, I did not feel justified in attempting to begin life again in Germany. I had not asked for a professorship or fellowship. They were offered me, and my ambition never went beyond securing what was necessary for my independence. In Germany I was supposed to have become quite wealthy; in England people knew how small my income really was, and wondered how I managed to live on it. They did not suppose that I had chiefly to depend on my pen in order to live as a professor is expected to live at Oxford. I could not see anything anomalous in a German holding a professorship in England. There were several cases of the same kind in Germany. Lassen (1800-1876), our great Sanskrit professor at Bonn, was a Norwegian by birth, and no one ever thought of his nationality. What had that to do with his knowledge of Sanskrit? Nor was I ever treated as an alien or as intruder at Oxford, at least not at that early time. As to myself, I had now obtained what seemed to me a small but sufficient income[24] with perfect independence. The quiet life of a quiet student had been from my earliest days my ideal in life. Even at school at Dessau, when we boys talked of what we hoped to be, I remember how my ideal was that of a monk, undisturbed in his monastery, surrounded by books and by a few friends. The idea that I should ever rise to be a professor in a university, or that any career like that of my father, grandfather, and other members of my family would ever be open to me, never entered my mind then. It seemed to me almost disloyal to think of ever taking their places. Even when I saw that there were no longer any Protestant monks, no Benedictines, the place of an assistant in a large library, sitting in a quiet corner, was my highest ambition.

I do not see why it should have been so, for all my relations and friends occupied high places in the public service, but as I had no father to open my eyes, and to stimulate my ambition—he having died before I was four years old—my ideas of life and its possibilities were evidently taken from my young widowed mother, whose one desire was to be left alone, much as the world tempted her, then not yet thirty years old, to give up her mourning and to return to society. Thus it soon became my own philosophy of life, to be left alone, free to go my own way, or like Diogenes, to live in my own tub. Here we see what I call the influence of circumstances, of surroundings, or as others call it, of environment.[25] This, however, is very different from atavism, as we shall see presently. Atavism also has been called a kind of environment, attacking us and influencing us from the past, and as it were, from behind, from the North in fact instead of the South, the East, and the West, and from all the points of the compass.

But atavism means really a very different thing, if indeed it means anything at all.

I must ease my conscience once for all on this point, and say what I feel about atavism and environment. Environment in the shape of friends, of locality, and other material circumstances, has certainly influenced my life very much, and I could never see why such a hybrid word as environment should be used instead of surroundings or circumstances. Creatures of circumstances would be far better understood than creatures of environment; but environment, I suppose, would sound more scientific. Atavism also is a new word, instead of family likeness, but unless carefully defined, the word is very apt to mislead us.

When it is said[4] that children often resemble their grandfathers or grandmothers more than their immediate parents, and that this propensity is termed atavism, this does not seem quite correct even etymologically, for atavus in Latin did not mean father or grandfather, but at first great-great-great-grandfather, [26]and then only ancestors; and what should be made quite clear is that this mysterious atavism should not be used by careful speakers, to express the supposed influence of parents or even grandparents, but that of more distant ancestors only, and possibly of a whole family.

Many biographers, such is the fashion now, begin their works with a long account not only of father and mother, but of grandparents and of ever so many ancestors, in order to show how these determined the outward and inward character of the man whose life has to be written. Who would deny that there is some truth, or at least some plausibility, in atavism, though no one has as yet succeeded in giving an intelligible account of it? It is supposed to affect the moral as well as the physical peculiarities of the offspring, and that here, too, physical and moral qualities often go together cannot be denied. A blind person, for instance, is generally cautious, but happy and quite at his ease in large societies. A deaf person is often suspicious and unhappy in society. In inheriting blindness, therefore, a man could well be said to have inherited cautiousness; in inheriting deafness, suspiciousness would seem to have come to him by inheritance.

But is blindness really inherited? Is the son of a father who has lost his eyesight blind, and necessarily blind? We must distinguish between atavistic and parental influences. Parental influences would mean the influence of qualities acquired by[27] the parents, and directly bequeathed to their offspring; atavistic influences would refer to qualities inherited and transmitted, it may be, through several generations, and engrained in a whole family. In keeping these two classes separate, we should only be following Weismann’s example, who denies altogether that acquired qualities are ever heritable. His examples are most interesting and most important, and many Darwinians have had to accept his amendment. Besides, we should always consider whether certain peculiarities are constant in a family or inconstant. If a father is a drunkard, surely it does not follow that his sons must be drunkards. Neither does it follow that all the children must be sober if the parents are sober. Of course, in ordinary conversation both parental and ancestral influences seem clear enough. But if a child is said to favour his mother, because like her he has blue eyes and fair hair, what becomes of the heritage from the father who may have brown eyes and dark hair? Whatever may happen to the children, there is always an excuse, only an excuse is not an explanation. If the daughter of a beautiful woman grows up very plain, the Frenchman was no doubt right when he remarked, C’était alors le père qui n’était pas bien, and if the son of a teetotaller should later in life become a drunkard, the conclusion would be even worse. In fact, this kind of atavistic or parental influence is a very pleasant subject for gossips, but from a scientific point of[28] view, it is perfectly futile. If it is not the father, it is the mother; if it is not the grandmother, it is the grandfather; in fact, family influences can always be traced to some source or other, if the whole pedigree may be dug up and ransacked. But for that very reason they are of no scientific value whatever. They can neither be accounted for, nor can they be used to account for anything themselves. Even of twins, though very like each other in many respects, one may be phlegmatic, the other passionate. Some scientists, such as Weismann and others, have therefore denied, and I believe rightly, that any acquired characters, whether physical or mental, can ever be inherited by children from their parents. Whatever similarity there is, and there is plenty, is traced back by him to what he calls the germ-plasm, working on continuously in spite of all individual changes. If that germ-plasm is liable to certain peculiar modifications in the father or grandfather, it is liable to the same or similar modifications in the offspring, that is, if the father could become a drunkard, so could the son, only we must not think that the post hoc is here the same as the propter hoc. If we compare the germ-plasm to the molecules constituting the stem or branches of a vine, its grapes and leaves in their similarity and their variety would be comparable to the individuals belonging to the same family, and springing from the same family tree. But then the grape we see would not be what the grape of last year, or[29] the grape immediately preceding it on the same branch, had made it, though there can be no doubt that the antecedent possibilities of the new grape were the same as those of the last. If one grape is blue, the next will be blue too, but no one would say that it was blue because the last grape was blue. The real cause would be that the molecules of the protoplasm have been so affected by long continued generation, that some of the peculiar qualities of the vine have become constant.

The child of a negro must always be a negro; his peculiarities are constant, though it may be quite true that the negro and other races are not different species, but only varieties rendered constant by immense periods of time. What the cause of these constant and inconstant peculiarities may be, not even Weismann has yet been able to explain satisfactorily.

The deafness of my mother and the prevalence of the misfortune in numerous members of her family acted on me as a kind of external influence, as something belonging to the environment of my life; it never frightened me as an atavistic evil. It justified me in being cautious and in being prepared for the worst, and so far it may be said to have helped in shaping or narrowing the course of my life. Fortunately, however, this tendency to deafness seems now to have exhausted itself. In my own generation there is one case only, and the next two generations, children and grandchildren of mine, show no[30] signs of it. If, on the other hand, my son was congratulated when entering the diplomatic service, on being the son of his father, it is clear that the difference between inherited and acquired qualities, so strongly insisted on by Weismann, had not been fully appreciated by his friends. Besides, my own power of speaking foreign languages has always been very limited, and I have many times declined the compliment of being a second Mezzofanti.[5] I worked at languages as a musician studies the nature and capacities of musical instruments, though without attempting to perform on every one of them. There was no time left for acquiring a practical familiarity with languages, if I wanted to carry on my researches into the origin, the nature and history of language. My own study of languages could therefore have been of very little use to me, nor did my son himself perceive such an advantage in learning to converse in French, Spanish, Turkish, &c. The facts were wrong, and the theory of atavism perfectly unreasonable as applied to such a case.

If the theory of atavism were stretched so far, it would soon do away with free will altogether. That heredity has something to do with our moral character, no one would deny who knows the influence of our national, nay even of racial character. We are Aryan by heredity; we might be Negroes or Chinese, and share in their tendencies. Animals [31]also have their instincts. Only while animals, like serpents for instance, would never hesitate to follow their innate propensity, man, when he feels the power of what we may call inherited human instinct, feels also that he can fight against it, and preserve his freedom, even while wearing the chains of his slavery. This may have removed some of Dr. Wendell Holmes’ scruples in writing his powerful story, Elsie Venner, and may likewise quiet the fears of his many critics.

I believe that language also—our own inherited language—exercises the most powerful influence on our reason and our will, far more powerful than we are aware of.

A Greek speaking Greek and a Roman speaking Latin would certainly have been very different beings from the Romance and French descendants of a Horace or a Cicero, and this simply on account of the language which they had to speak, whether Greek, Latin, French, or Spanish. We cannot tell whether the original differentiation of language, symbolized by the story of the Tower of Babel, took place before or after the racial differentiation of men. Anyhow it must have taken place in quite primordial times. Without speaking positively on this point, I certainly hold as strongly as ever that language makes the man, and that therefore for classificatory purposes also language is far more useful than colour of skin, hair, cranial or gnathic peculiarities. Whether it be true that with every new[32] language we speak we become new men, certain it is that language prepares for us channels in which our thoughts have to run, unless they are so powerful as to break all dams and dykes, and to dig for themselves new beds.

For a long time people would not see that languages can be classified; and as languages always presuppose speakers of language, these speakers also can be classified accordingly. It is quite true that some of these Aryan speakers may in some cases have Negro blood and Negro features, as when a Negro becomes an English bishop. Conquered tribes also may in time have learnt to speak the language of their conquerors, but this too is exceptional, and if we call them Aryas, we do not commit ourselves to any opinion as to their blood, their bones, or their hair. These will never submit to the same classification as their speech, and why should they? Nor should it be forgotten that wherever a mixture of language takes place, mixed marriages also would most likely take place at the same time. But whatever confusion may have arisen in later times in language and in blood, no language could have arisen without speakers, and we mean by Aryas no more than speakers of Aryan languages, whatever their skulls or their hair may have been. An Octoroon, and even a Quadroon, may have blonde waving hair, but if he speaks English he would be classified as Aryan, if Berber as a Negro. But who is injured by such a classification?[33] Let blood and skulls and hair and jaws be classified by all means, but let us speak no longer of Aryan skulls or Semitic blood. We might as well speak of a prognathic language.

While fully admitting, therefore, the influence which family, nationality, race, and language exercise on us, it should be clearly perceived that habits acquired by our parents are not heritable, that the sons of drunkards need not be drunkards, as little as the sons of sober people must be sober. But though biographers may agree to this in general they seem inclined, to hold out very strongly for what are called special talents in certain families. This subject is decidedly amusing, but it admits of no scientific treatment, as far as I can see.

The grandfather of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy for instance, though not a composer, was evidently a man of genius, a philosopher of considerable intellectual capacity and moral strength. The father of the composer was a rich banker at Berlin, and he used to say: “When I was young I was the son of the great Mendelssohn, now that I am old, I am the father of the great Mendelssohn; then what am I?” Even a poor man to become a rich banker must be a kind of genius, and so far the son may be said to have come of a good stock. But the great musical talent that was developed in the third generation both in Felix and his sisters, failed entirely in his brother, who, to save his life, could never have sung “God save the Queen.” In the little[34] theatrical performances of the whole family for which Felix composed the music, and his sister Fanny (Hensel) some of the songs, the unmusical brother—was it not Paul?—had generally to be provided with some such part as that of a night watchman, and he managed to get through his song with as much credit as the Nachtwächter in the little town of Germany, where he sang or repeated, as I well remember, in his cracked voice:

I have known in my life many musicians and their families, but I remember very few instances indeed, where the son of a distinguished musician was a great musician himself. If the children take to music at all they may become very fair musicians, but never anything extraordinary. The Bach family may be quoted against me, but music, before Sebastian Bach, was almost like a profession, and could be learned like any other handicraft.

Nor are the cases of painters being the sons of great painters, or of poets being the sons of great poets, more numerous. It seems almost as if the[35] artistic talent was exhausted by one generation or one individual, so that we often see the sons of great men by no means great, and if they do anything in the same line as their fathers, we must remember that there was much to induce them to follow in their steps without admitting any atavistic influences.

For the present, I can only repeat the conclusion I arrived at after weighing all the arguments of my friends and critics, namely, to continue my Recollections much as I began them, to try to explain what made me what I am, to describe, in fact, my environment; though as my years advance, and my labours and plans grow wider and wider, I shall, no doubt, have to say a great deal more about myself than in the volumes of Auld Lang Syne. In fact, my Recollections will become more and more of an autobiography, and the I and the Autos will appear more frequently than I could have wished.

In an autobiography the painter is of course supposed to be the same as the sitter, but quite apart from the metaphysical difficulties of such a supposition, there is the physical difficulty when the writer is an old man, and the model is a young boy. Is the old man likely to be a fair judge of the young man, whether it be himself or some one else? As a rule, old men are very indulgent, while young men are apt to be stern and strict in their judgments. The very fact that they often invent excuses for themselves shows that they feel that they[36] want excuses. The words of the Preacher, vii. 16: “Be not righteous over much; neither make thyself over wise: why shouldest thou destroy thyself? Be not over much wicked, neither be thou foolish: why shouldest thou die before thy time?” are evidently the words of an old man when judging of himself or of others. A young man would have spoken differently. He would have made no allowance; for anything like compassion for an erring friend is as yet unknown to him. In an autobiography written by an old man there is therefore a double danger, first the indulgence of the old man, and secondly the kindly feeling of the writer towards the object of his remarks.

All these difficulties stand before me like a mountain wall. And it seems better to confess at once that an old man writing his own life can never be quite just, however honest he tries to be. He may be too indulgent, but he may also be too strict and stern. To say, for instance, of a man that he has not kept his promise, would be a very serious charge if brought against anybody else. Yet my oldest friend in the world knows how many times he has made a promise to himself, and has not only not kept it but has actually found excuses why he did not keep it. The more sensitive our conscience becomes, the more blameworthy many an act of our life seems to be, and what to an ordinary conscience is no fault at all, becomes almost a sin under a fiercer light.[37]

This changes the moral atmosphere of youth when painted by an old man, but the physical atmosphere also assumes necessarily a different hue. Whether we like it or not, distance will always lend enchantment to the view. If the azure hue is inseparable from distant mountains and from the distant sky, we need not wonder that it veils the distant paradise of youth. A man who keeps a diary from his earliest years, and who as an old man simply copies from its yellow pages, may give us a very accurate black and white image of what he saw as a boy, but as in old faded photographs, the life and light are gone out of them, while unassisted memory may often preserve tints of their former reality. There is life and light in such recollections, but I am willing to admit that memory can be very treacherous also. Thus in my own case I can vouch that whatever I relate is carefully and accurately transcribed from the tablets of my memory, as I see them now, but though I can claim truthfulness to myself and to my memory, I cannot pretend to photographic accuracy. I feel indeed for the historian who uses such materials unless he has learnt to make allowance for the dim sight of even the most truthful narrators.

I doubt whether any historian would accept a statement made thirty years after the event without independent confirmation. I could not give the date of the battle of Sadowa, though I well remember reading the full account of it in the Times[38] from day to day. I can of course get at the date from historical books, and from that kind of artificial memory which arises by itself without any memoria technica. There is a favourite German game of cards called Sixty-six, and it was reported that when the French in 1870 shouted À Berlin, the then Crown-Prince who had won the battle of Sadowa, or Königgrätz, said: “Ah, they want another game of Sixty-six!” that is they want a battle like that of Sadowa. In this way I shall always remember the date of that decisive battle. But I could not give the date of the Crimean battles nor a trustworthy account of the successive stages of that war. I doubt whether even my old friend, Sir William H. Russell, could do that now without referring to his letters in the Times. After thirty years no one, I believe, could take an oath to the accuracy of any statement of what he saw or heard so many years ago.

All then that I can vouch for is that I read my memory as I should the leaves of an old MS. from which many letters, nay, whole words and lines have vanished, and where I am often driven to decipher and to guess, as in a palimpsest, what the original uncial writing may have been. I am the first to confess that there may be flaws in my memory, there may be before my eyes that magic azure which surrounds the distant past; but I can promise that there shall be no invention, no Dichtung instead of Wahrheit, but always, as far as in me lies, truth.[39] I know quite well that even a certain dislocation of facts is not always to be avoided in an old memory. I know it from sad experience. As the spires of a city—of Oxford for instance—arrange themselves differently as we pass the old place on the railway, so that now one and now the other stands in the centre and seems to rise above the heads of the rest, so it is with our friends and acquaintances. Some who seemed giants at one time assume smaller proportions as others come into view towering above them. The whole scenery changes from year to year. Who does not remember the trees in our garden that seemed like giants in our childhood, but when we see them again in our old age, they have shrunk, and not from old age only?

And must I make one more confession? It is well known that George the Fourth described the battle of Waterloo so often that at last he persuaded himself that he had been present, in fact that he had won that battle. I also remember Dr. Routh, the venerable president of Magdalen College, who died in his hundredth year, and who had so often repeated all the circumstances of the execution of Charles I, that when Macaulay expressed a wish to see him, he declined “because that young man has given quite a wrong account of the last moments of the king,” which he then proceeded to relate, as if he had been an eye-witness throughout.

Are we not liable to the same hallucination, though, let us hope, in a more mitigated form?[40] Have we never told a story as if it were our own, not from any wish to deceive, but simply because it seemed shorter and easier to do so than to explain step by step how it reached us? And after doing that once or twice, is there not great danger of our being surprised at somebody else claiming the story as his own, or actually maintaining that it was he who told it to us?

Not very long ago I remember reading in a journal a story of the Duke of Wellington. His servant had been sent before to order dinner for him at an out-of-the-way hotel, and in order to impress the landlord with the dignity of his coming guest, he had recited a number of the Duke’s titles, which were very numerous. The landlord, thinking that the Duke of Vittoria, the Prince of Waterloo, the Marquis of Torres Vedras, and all the rest, were friends invited to dine with the Duke of Wellington, ordered accordingly a very sumptuous banquet to the great dismay of the real Duke. This may or may not be a very old and a very true story; all I know is that much the same thing was told at Oxford of Dr. Bull, who was Canon of Christ Church, Canon of Exeter, Prebendary of York, Vicar of Staverton, and lastly, the Rev. Dr. Bull himself. Dinner was provided for each of these persons, and we are told that the reverend pluralist had to eat all the dishes on the table and pay for them. This also may have been no more than one of the many “Common-roomers” which abounded[41] in Oxford when Common Rooms were more frequented than they are now. But what I happen to know as a fact is that Dean Stanley received no less than four invitations to a hall at Blenheim, addressed A. P. Stanley, Esq., the Rev. A. P. Stanley, Canon Stanley, Professor Stanley, all evidently copied from some books of reference.

I may perhaps claim one advantage in trying to describe what happened to myself in my passage through life. From the earliest days that I can recollect, I felt myself as a twofold being—as a subject and an object, as a spectator and as an actor. I suppose we all talk to ourselves, and say to our better and worse selves, O thou fool! or, Well done, my boy! Well this inward conversation began with me at a very early time, and left the impression that I was the coachman, but at the same time the horse too which he drove and sometimes whipped very cruelly. And this phase of thought, or rather this state of feeling, seems soon to have led me on to another view which likewise dates from a very early time, though it afterwards vanished. As a little boy, when I could not have the same toys which other boys possessed, I could fully enjoy what they enjoyed, as if they had been my own. There is a German phrase, “Ich freue mich in deiner Seele,” which exactly expressed what I often felt. It was not the result of teaching, still less of reasoning—it was a sentiment given me and which certainty did not leave me till much later in life, when[42] competition, rivalry, jealousy, and envy seemed to accentuate my own I as against all other I’s or Thou’s. I suppose we all remember how the sight of a wound of a fellow creature, nay even of a dog, gives us a sharp twitch in the same part of our own body. That bodily sympathy has never left me, I suffer from it even now as I did seventy years ago. And is there anybody who has not felt his eyes moisten at the sudden happiness of his friends? All this seems to me to account, to a certain extent at least, for that feeling of identity with so-called strangers, which came to me from my earliest days, and has returned again with renewed strength in my old age. The “know thyself,” ascribed to Chilon and other sages of ancient Greece, gains a deeper meaning with every year, till at last the I which we looked upon as the most certain and undoubted fact, vanishes from our grasp to become the Self, free from the various accidents and limitations which make up the I, and therefore one with the Self that underlies all individual and therefore vanishing I’s. What that common Self may be is a question to be reserved for later times, though I may say at once that the only true answer given to it seems to me that of the Upanishads and the Vedanta philosophy. Only we must take care not to mistake the moral Self, that finds fault with the active Self, for the Highest Self that knows no longer of good or evil deeds.

Long before I had worked and thought out this[43] problem as the fundamental truth of all philosophy, it presented itself to me as if by intuition, long before I could have fathomed it in its metaphysical meaning. I had just heard of the death of a dear little child, and was standing in our garden, looking at a rose-bush, covered in summer with hundreds of rose-buds and rose-flowers. While I was looking I broke off one small withered bud from the midst of a large cluster of roses, and after I had done so a question came to me, and I said to myself, What has happened? Is it only that one small bud is dead and gone, or have not all the other roses been touched by the breath of death that fell on it? Have they not all suffered from the death of their sister, for they all spring from the same stem, they all have their life from the same source? And if one rose suffers, must not all the others suffer with it? Then all the buds and flowers of the cluster seemed to me to become one, as it were a family of roses, and each single bud seemed but the repetition of the same thing, the manifestation of the same thought, namely the thought of the rose. But my eyes were carried still further, and the stem from which the bunch of roses sprang was lost with other stems in a branch, and it was that branch on which all the roses of the branchlets and stems depended, and without which they could not flower or exist. The single roses thus became identified with the branch from which they had sprung, and by which they lived. I wondered more and more,[44] and after another look all the branches with all their branchlets became absorbed in the stem, and the stem was the tree, and the tree sprang from a seed, or as it is now called, the protoplasm; but beyond that seed there was nothing else that the eye could see or the mind could grasp. And while this vision floated before my eyes I thought of my little friend, and the home from which she had been broken off, and the same vision which had changed the rose-bush with all its flowers, and buds, and branchlets, and branches, into a stem and a tree, and at last into one invisible germ and seed, seemed now to change my little friend and her brothers and sisters, her parents too and all her family, into one being which, like an old oak tree, started from an invisible stem, or an invisible seed, or from an invisible thought, and that divine thought was man, as the other divine thought had been rose.

Perhaps I did not see it so fully then as I see it now, and I certainly did not reason about it. I simply felt that in the death of my little friend, something of myself had gone, though she was no relation, but only a stray human friend. We see many things as children which we cannot see as grown-up men and women, for, as Longfellow said, “the thoughts of youth are long long thoughts.” Nay, I feel convinced that He who spoke the parable of the vine had seen the same vision when He said: “I am the vine, ye are the branches. Abide in Me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear[45] fruit of itself except it abide in the vine, no more can ye, except ye abide in Me.” And it is on this vision, or this parable of the vine, that immediately afterwards follows the lesson, “Love one another, as I have loved you.” In loving one another we are in truth loving the others as ourselves, as one with ourselves; and while we are loving Him who is the vine, we are loving the branches, ourselves—aye, even our own little selves.

Such vague visions or intuitions often remain with us for life, but while they seem to be the same, they vary as we vary ourselves. We imagine we saw their deepest meaning from the first, but, like a parable, they gain in meaning every time they come back to us.

[1] Deutsche Rundschau, Feb., 1900, p. 249.

[2] Driesch, Biologisches Centralblatt, 1896, p. 335.

[3] As giving a clear and complete abstract of my writings I may now recommend M. Montcalm’s L’origine de la Pensée et de la Parole, Paris, 1900.

[4] Oxford Dictionary, s. v.; J. Rennie, Science of Gardening, p. 113.

[5] Science of Language, vol. i. p. 24 (1861).

In a small town such as Dessau was when I lived there as a child and as a boy, one lived as in an enchanted island. The horizon was very narrow, and nothing happened to disturb the peace of the little oasis. The Duchy was indeed a little oasis in the large desert of Central Germany. The landscape was beautiful: there were rivers small and large—the Mulde and the Elbe; there were magnificent oak forests; there were regiments of firs standing in regular columns like so many grenadiers; there were parks such as one sees in England only. The town, the capital of the Duchy of Anhalt-Dessau, had been cared for by successive rulers—men mostly far in advance of their time—who had read and travelled, and brought home the best they could find abroad. Their old castle, centuries old, over-awed the town; it was by far the largest building, though there were several other smaller places in the town for members of the ducal family. All the public buildings, theatres, libraries, schools, and barracks, had been erected by the Dukes, as well as several private residences intended for some of the higher officials. The whole town was, in fact, the creation[47] of the Dukes; the whole ground on which it stood had been originally their property, but it was mostly held as freehold by those who had built their own private houses on it. No one would have built a house on leasehold land, and several of the houses were of so substantial a character that one saw they had been intended to last for more than ninety-nine years. The same family often remained in their house for generations, and the different stories were occupied by three generations at the same time—by grandparents, parents, and children. In this small town I was born on December 6, 1823. My father, Wilhelm Müller, was Librarian of the Ducal Library, and one of the most popular poets in Germany. A national monument was erected to his memory at Dessau in the year 1891, nearly a hundred years after his birth.

MY FATHER

What a blessing it would be if such a rule were followed with all great men, who seem so great at the time of their death, and who, a hundred years later, are almost forgotten, or at all events appreciated by a small number of admirers only. This Monument- and Society-mania is indeed becoming very objectionable, for if for some time there has been no room for tombs and statues in Westminster Abbey, there will soon be no room for them in the streets of London. The result is that many of the people who walk along the Thames Embankment, particularly foreigners, often ask, “Cur?” when looking at the human idols in bronze and marble[48] put up there; while historians, remembering the really great men of England, would ask quite as often, “Cur non?” There is a curious race of people, who, as soon as a man of any note dies, are ready to found anything for him—a monument, a picture, a school, a prize, a society—to keep alive his memory. Of course these societies want presidents, members of council, committees, secretaries, &c., and at last, subscriptions also. Thus it has happened that the name of founder (Gründer) has assumed, particularly in Germany, a perfume by no means sweet. Those who are asked to subscribe to such testimonials know how disagreeable it is to decline to give at least their name, deeply as they feel that in giving it they are offending against all the rules of historical perspective. I should not say that my father was one of the great poets of Germany, though Heine, no mean critic, declared that he placed his lyric poetry next to that of Goethe. Besides, he was barely thirty-three when he died. He had been a favourite pupil of F. A. Wolf, and had proved his classical scholarship by his Homerische Vorschule, and other publications. His poems became popular in the true sense of the word, and there are some which the people in the street sing even now without being aware of the name of their author. Schubert’s compositions also have contributed much to the wide popularity of his Schöne Müllerin and his Winterreise, so that though it might truly be said of him that he wanted[49] no monument in bronze or stone, it seemed but natural that a small town like Dessau should wish to honour itself by honouring the memory of one of its sons. In the company of Mendelssohn, the philosopher, and of F. Schneider, the composer, a monument of my father in the principal street of his native town, and before the school in which he had been a pupil and a teacher, could hardly seem out of place. That the Greek Parliament voted the Pentelican marble for the poet of the Griechenlieder, as it had done for Lord Byron, was another inducement for his fellow citizens to do honour to their honoured poet. He died when I was hardly four years old, so that my recollection of him is very faint and vague, made up, I believe, to a great extent, of pictures, and things that my mother told me. I seem to remember him as a bright, sunny, and thoroughly joyful man, delighted with our little naughtinesses. One book I still possess which he bought for me and which was to be the first book of my library. It was a small volume of Horace, printed by Pickering in 1820. It has now almost vanished among the 12,000 big volumes that form my library, but I am delighted that I am still able, at seventy-six, to read it without spectacles. I think I remember my father taking my sister and me on his knees, and telling us the most delightful stories, that set us wondering and laughing and crying till we could laugh and cry no longer. He had been a fellow worker with the brothers Grimm,[50] and the stories he told were mostly from their collection, though he knew how to embellish them with anything that could make a child cry and laugh.