Project Gutenberg's Harper's Young People, March 23, 1880, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Harper's Young People, March 23, 1880

An Illustrated Weekly

Author: Various

Release Date: March 26, 2009 [EBook #28417]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S YOUNG PEOPLE, MAR 23, 1880 ***

Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 21. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, March 23, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Sunshine on the meadow,

Sunshine on the sea;

Green buds on the rose-bush,

Blossoms on the tree.

Two wee children singing

In a rapt delight—

One as fair as morning,

One as dark as night.

Hymn-book held between them

With the greatest care,

Though they can not read a word

That is printed there.

"Jesus, Saviour, meek and mild,

Friend of ev'ry little child,

Once a child Thyself, we pray

Thou wilt guard us day by day;

For such helpless things are we,

We can only sing to Thee!"

Standing in the doorway,

Arnak smiles to hear

Bird-like voices blending

Sweet and loud and clear.

"'Pears to me de angels

Mus' be lis'nin' too—

Lis'nin' an' a-lookin'

From de hebbens blue;

Lookin' an' a-smilin'

At de pretty sight;

An' in dar eyes—bress de Lord!—

Bofe dem chillun's white."

[Pg 266]

"Come, Nell, and you too, Harry. I have planned a delightful trip for you, and we must be off bright and early."

"Where—where, Miss Eleanor?" cried both children together.

"To the large greenhouses just beyond the city line. You remember the minister said on Sunday, 'Let every person bring flowers, if but a single lily or a rose, to make God's house beautiful on Easter-day'? There are millions of flowers in blossom now at the greenhouses, and I wish you to see them, and learn how the florists make them bloom out of season."

"I hope you will tell us something about it," said Harry, as we rattled swiftly over the rails in the steam-dummy; "that is, when we get out of this noisy old trap."

In a few minutes we alighted at the city line, and Harry, taking my arm, declared himself ready for more "flower talk."

"Suppose," said I, "that a florist wishes to have several thousand plants in bloom for Easter, does he allow them plenty of water and sunshine, and opportunity to bloom several months in advance of the day? No; he stows them all away to rest, or sleep, as he calls it, for weeks and weeks, in cool, dry, shady places, some on shelves, some in sand, and some in pots 'in cool houses.'

"After a time the bulbs are taken out of the sand, and placed in earth, and with the other plants are allowed to enjoy a little warmth and sunshine.

"The rose-bushes are pruned, bound, and tied in trim forms, and placed in rows, and though destitute of foliage, look so healthy and neat one can not but admire them. In a week or two, as if by magic, thousands of buds are swelling and bursting into leaf on every stem.

"Five weeks ago I visited the greenhouses we are now going to, and as I stood in the Easter 'roseries,' I thought it must be quite delightful to be a young rose in training for Easter, the sunshine was so warm and golden, the air so soft and dewy sweet. Every bush showed signs of coming buds—very, very tiny, but they were there. The bulb houses were stocked with rows and rows of cherry-red pots filled with rich brown mould; in some the point of a tulip or hyacinth leaf peered up green and bright, in others there were already brave crowns of strong leaves.

"'Ah,' thought I, 'these will surely please the florist's eye;' but I assure you they had a very different effect, for he looked at them with a frown that said, plainer than words, 'My brave young folks, wouldn't you like to blossom before Easter, and spoil my fine show for me? Indeed you shall not.' He thought that, of course; for the next minute he cried out, 'John, take these forward bulbs and put them back in the "cold house."'"

"What a pity!" murmured Nell.

"Not at all," replied I, "for soon they would have had spikes of fine blossoms; then Madam Hyacinth and Mr. Tulip might bid farewell to all thought of going to church on Easter-day, for long before that time their gay clothes would be faded and spoiled."

"What is the 'cold house'?" inquired Harry.

"A greenhouse where the mercury stands below 50°. Jonquils, tulips, hyacinths and lilies, and most other Easter plants, need warmer air than that to grow rapidly in. The 'cold houses' are not neglected, for they have a certain amount of moisture and sunshine allowed them too, or the plants would die.

"As the happy day draws nearer and nearer, great activity reigns in the greenhouses: batches of plants are seen going back to the 'warm houses,' and such a showering, sponging, snipping and training, and general petting going on, that if plants had any brains, they would go mad with it all. But as they are not troubled with brains, they enjoy the warm sunshine, and the gentle vapors that rise steaming from the earth, and just set themselves to blossoming and looking as lovely as they can."

"So it takes earth, sunshine, wind, and water to raise flowers?" said Harry.

"Yes, and labor and knowledge."

Here the flower lecture ended, for we were at the greenhouse gates. In another moment a door was opened, and we were ushered into a world of beauty.

"How lovely!" cried Nell, looking down the green aisles of the "azalea house."

"They look like swarms of great white butterflies among the dark leaves," remarked Harry.

"Or giant snow-flakes ready to melt or blow away," suggested Nell.

"If you call those white azaleas so handsome, I wonder what you will say to these!" exclaimed the florist, opening wide the door of a "lily house."

"Come here, children," cried I. "Was there ever a more heavenly sight than these hosts of lilies holding up their white chalices to the flooding sunshine?"

"Or anything more delicious?" murmured Nell, bending lovingly over a group of Ascension lilies.

Further on there were ranks and ranks of tall callas, stately as sceptred queens, starry narcissus, white as snow, and jasmine bouvardias, with ivory tube-like blossoms in fragrant clusters.

Something "new, and strange, and sweet" greeted us at every step. Here it was a Deutzia, with starry cup-like blossoms; there a Spiræa, with spikes of milk-white plumes; here sprays of creamy Lantanas, and yonder clusters of tasselled Ageratum.

"Don't go yet," pleaded Nell and Harry, as I turned to leave.

"You'll admire the 'rosery' more than this," said the gardener, opening another door, and standing aside.

A marvellous fragrance saluted us as we looked down the long ranks of tall nyphetos shrubs laden with hundreds of silken buds and opening blossoms, in every shade from lemon to purest white.

How dainty!—how exquisite! Here and there a full-blown rose showed its closely folded centre, and long slender petals so delicately hung that a breath might scatter them.

Along the walls were trained vine-like Marshal Neils, with great golden buds and blossoms, while below rows of Safranos lifted fragrant cups rivalling in tint the bloom of an apricot's cheek.

In a second "rosery" we were fairly smothered in sweets. Scores of pale pink Hermanos, blushing Bon Silenes, and Plantiers—living balls of snow—and white Lamarques mingled their spicy breaths in one soft cloud of incense. Pink and white, ruby, buff, and golden, they hung and nodded on every stem, till, like Aladdin in the magician's garden, we knew not which way to turn.

As for the "carnation houses," they made us think of spice islands floating on seas of green; the "pansy houses" were beds of gold and amethyst; the "violet houses" and "smilax greeneries," perfect visions of spring.

There were, besides, ferns, lilies-of-the-valley, camellias on tall tree-like shrubs that made quite a respectable forest in a house by themselves, and rows upon rows of dainty pink, crimson, and white primroses.

Like a true artist, the florist had reserved his most wonderful picture for the last. As he opened the door of an Easter bulb house, he said, "What do you think of that?"

With a cry of delight, as the glory of colors burst upon her, Nell stood entranced in the doorway. Down the middle of the house hundreds and hundreds of potted tulips flamed and glowed with vivid dyes.

On either side the long walks, on the shelves, stood rows and rows of hyacinths in splendid bloom.[Pg 267]

Here vases and urns of yellow, purple, saffron, scarlet, pink and white, pied and streaked with living flames.

There bells of ivory, azure, lilac, rose, and buff, fluted, feathered, fringed, and spicy sweet.

It seemed as if some fairy alchemist had melted in magic crucible topaz, ruby, sapphire, gold, and amethyst, to deck each fragrant cup and bell.

There was a terrible stir in the barracks of the —th Native Infantry at Sekundurabad (Alexander's Town) one bright morning at the beginning of the "dry season." Some money had been stolen from the officers' quarters during the night, and all that could be made out about it was that the theft must have been committed by one of those inside the building, for nobody had got in from without.

The officers' native servants and the sepoy soldiers, to a man, stoutly declared that they knew nothing about it; and the officer of the day, with very great disgust, went to make his report to the Colonel.

Now the Colonel was a hard-headed old Scotchman, who had spent the best part of his life in India, and knew the Hindoos and their ways by heart. He heard the story to an end without any sign of what he thought of it, except a queer twinkle in the corner of his small gray eye; and then he gave orders to turn out the men for morning parade.

When the Colonel appeared on the parade-ground, everybody expected that the first thing would be an inquiry about the stolen money; but that was not the old officer's way. Everything went on just as usual, and the thief probably chuckled to himself at the idea of getting off so easily. But if so, he chuckled a little too soon. Just as the parade was over, and the men were about to "dismiss," the Colonel stepped forward, and shouted, "Halt!"

The men wonderingly obeyed. The Colonel planted himself right in front of the line (carrying a small bag under his arm, as was now noticed for the first time), and running his eye keenly over the long ranks of white frocks and dark faces, spoke to them in Hindoostanee:

"Soldiers! I find there are dogs among you who are not 'true to their salt,' and after taking the money of the Ranee of Inglistan [Queen of England], steal from her officers. But such misdeeds never go unpunished. Last night" (here the Colonel's tone suddenly became very deep and solemn) "I had a dream. I dreamed that a black cloud hovered over me, and out of it came a figure—the figure of Kali."

At the name of this terrible goddess (who holds the same place in the Brahmin religion as the Evil One in our own) the swarthy faces turned perfectly livid, and more than one stalwart fellow was seen to shiver from head to foot.

"'There is a thief among your soldiers,' she said, 'and I will teach you how to detect him. Give each of your men a splinter of bamboo, and the thief, let him do what he may, will be sure to get the longest; and when he is found, let him dread my vengeance.'"

By this time every soldier on the ground was looking so frightened that had the Colonel expected to detect the thief by his looks, he might have thought the whole regiment equally guilty. But his plan was far deeper than that. At his signal each man in turn drew a bamboo chip from the bag which the Colonel held; and when all were supplied, he ordered them to come forward one by one, and give back the chips which they had drawn.

He was obeyed; but scarcely had a dozen men passed, when the Colonel suddenly sprang forward, seized a tall Rajpoot by the throat, and shouted, in a voice of thunder, "You're the man!"

"Mercy, mercy, Sahib" (master), howled the culprit, falling on his knees. "I'll bring back the money—I'll bear any punishment you please—only don't give me up to the vengeance of Kali."

"Well," said the Colonel, sternly, "I'll forgive you this once; but if you're ever caught again, you know what to expect. Dismiss!"

"I say, C——, how on earth did you manage that?" asked the senior Major, as he and the Colonel walked away together; "I suppose you don't want me to believe that you really did get that idea in a dream?"

"Hardly," laughed the Colonel. "The fact is, those bamboo chips were all exactly the same length; and the thief, to make sure of not getting the longest, bit off the end of his, and so I knew him at once. Take my word for it, there'll be no more thieving in the regiment while I'm its Colonel."

And indeed there never was.

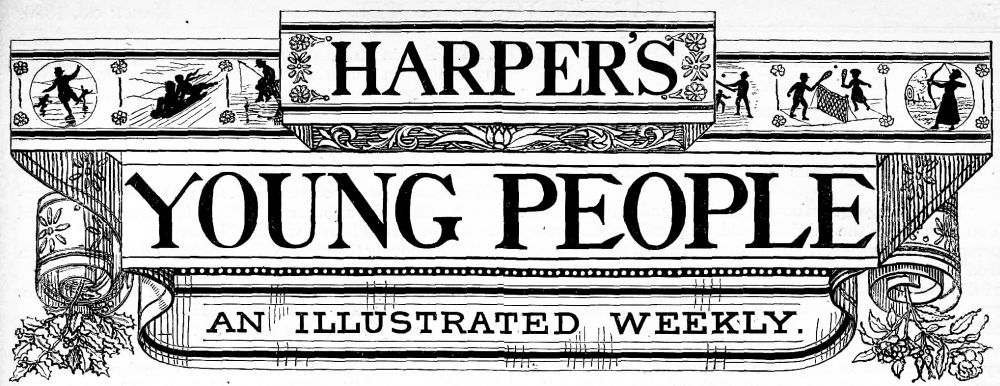

It was well for Austin that he had been struck by the small coal instead of the heavier pieces, or he might have been killed outright; as it was, after a dash of cold water, and a short rest in his bunk, he was almost as sound as before. But the accident had worse results than a few bruises. He was at once set down as an "awkward landlubber," dismissed from his coal-shovelling, and ordered to do duty in the lamp-room.

STORE-ROOM.

STORE-ROOM.

This was a dismal hole in the lowest part of the ship, where even what little light there was had to struggle through an iron grating. Behind the counter that ran half way round it stood several large iron tanks, strongly padlocked, labelled "Soap," "Oil," "Waste," "Lamp Wicks," etc. The floor was covered with various necessaries for engine use, and from the beams overhead swung lamps of all shapes and sizes, while the walls were covered with bolts, bars, hammers, and tools of every kind.

This pleasant place usually fell to the charge of some one who was fit for nothing else; and its present occupant was a lanky youth known as "Monkey"—a name fully warranted by his narrow watery eyes, enormous under-jaw, and huge projecting bat-like ears. He had been cruising backward and forward in the Arizona for years, till he seemed quite to belong to her; and although he disappeared as soon as she reached port, he always found out the day of her departure in time to join her again—how, no one knew, for he could neither read nor write.

Frank's appointment, of course, displaced Monkey, and neither was pleased with the change. Monkey much preferred even the dismal lamp-room (where he had only to serve out a certain quantity of stores daily, and to see that nothing was lost or stolen) to the harder work of scrubbing the engine-room, which now fell to his share; while Austin, used as he was to out-door exercise, felt quite miserable in this dungeon-like hole, where he could not even see to read. He was on duty from dawn till dusk, and even liable to be roused up at night should anything be wanted. His meals were given him after all the rest were served, and only very rarely did he get the chance of asking[Pg 268] a question, or learning anything that he wished.

Nor did his troubles end here. The men, who in Monkey's time had been allowed to help themselves pretty freely to the ship's stores, were enraged at finding that their new store-keeper could neither be bribed nor bullied into letting them have anything without orders. One of Frank's greatest troubles was the giving out of soap—a priceless luxury in the forecastle of a steamer, where the "grit," coal-dust, and irritating brine are unbearable if not promptly washed off. For a piece of soap (the ship's allowance being unusually small), shirts, stockings, and even tobacco, were gladly bartered; and those who had been shrewd enough to lay in a stock before sailing drove a brisk trade.

This gave our friend Monkey a chance which he was not slow to use. He began by hinting to the crew that Frank's care of the stores was meant to "curry favor" with the officers; and then he went on to losing or stealing whatever he could, and laying the blame on Austin. Nor were these the most serious tokens of his ill-will. One day he managed to give Frank a push which sent him down through a trap-door, though he luckily escaped unhurt. Another time, a similar trick hurled him into the well in which the ship's pump worked, and he only avoided serious injury by clinging to the shaft.

At last, as Frank was serving out stores one afternoon, Monkey suddenly darted off with a bar of soap, and being pursued into the engine-room by Austin, declared that the latter had been about to sell it to one of the men, and that he had just come in time to prevent him—a statement confirmed by the sailors. In vain poor Frank denied the charge; he was roughly ordered to hold his tongue, and give up the store-room keys to their former possessor, Monkey.

This was hard indeed; but, as the proverb says, "It is a long lane that has no turning," and our hero's affairs suddenly took a turn which neither he nor any one else could have foreseen.

The pride of a steamer is her machinery, and at all hours of the day men may be seen polishing it with balls of cotton "waste," till it shines like silver; but if you venture to touch the glittering surface, you find it burning hot, and scorch your fingers pretty smartly. One day Frank was polishing the broad round top of the cylinder, protected by a thick rope mat from the burning metal, when Monkey, sneaking up behind, suddenly jerked away the mat, throwing him right on to the hot surface. Smarting with pain, Austin sprang to his feet, and regardless of his enemy's superior bulk and strength, flew at him like a tiger. The two grappled, and rolled on the floor, Frank undermost.

FRANK'S FIGHT WITH "MONKEY."

FRANK'S FIGHT WITH "MONKEY."

Monkey's small, cunning eyes gleamed wickedly as he saw that they were close to the edge of the "crank-pit" (the space in which the crank of the shaft revolves), and he exerted all his strength to fling Austin into it. But the latter, who had not played foot-ball for nothing, suddenly wrenched himself free, and dodging round behind his enemy, sprang upon his back, and grasped his throat like a vise. Down went the valiant Monkey upon the hard grating with a whack that made his big mouth swell up bigger than ever; and, pinned beneath Frank's knee, he howled shrilly for help.

His cries were answered by a loud laugh from the sky-light above, through which several of the crew had been watching the combat. At the same moment the second engineer appeared on the scene.

"What! fighting? You young imps, is that how you do your work? Here, Williams, take 'em both to the first officer, and report 'em for fighting on duty."

"I, Henry, born at Monmouth,

Shall small time reign and much get.

But Henry of Windsor shall long reign and lose all,

But as God will, so be it."

This strange bit of doggerel is said to have been composed and repeated by King Henry V. of England on the birth of his only child Henry. The baby first saw the light of day in Windsor's royal palace, where he was born on the 6th of December, 1421, and was welcomed with delight by the English nation as the son and heir of their idolized King.

Before little Henry was more than nine months old, the King his father was dead. The poor little baby was already King of England, and within another month his grandfather, Charles VI. of France, was also dead, and another heavy crown was burdening the infant's brow.

No sooner had Queen Katherine, the mother of the little King, fulfilled her duty of seeing the funeral rites belonging to her husband properly accomplished, than she hastened to Windsor to embrace her child, and pass in solitude the early months of her widowhood. She was only in her twenty-first year, and had many arduous duties before her. The first of these was to see her baby King properly received and acknowledged as their sovereign by the nation. The sanction of Parliament was required, and accordingly the Queen removed from Windsor to London, passing through the city on a moving throne drawn by white horses, and surrounded by all the princes and nobles of England. In her lap was seated the infant King, and "those infant hands," says one of the chroniclers, "which could not yet feed himself, were made capable of wielding a sceptre, and he who was beholden to nurses for milk, did distribute support to the law and justice of the realm!" "The Queen, still holding her baby on her knee, was enthroned among the lords, whom, by the chancellor, the little King saluted, and spake to them his mind at large by means of another's tongue." It was declared that during this scene in Parliament the baby King conducted himself with marvellous quietness and gravity. Henry VI. had been already proclaimed King of France, at Paris, before even he thus held his first Parliament on his mother's lap. For as soon as the last service had been performed over the dead body of Charles VI., and the body lowered into the vault belonging to the royal Kings of France, the impressive ceremony followed of the ushers belonging to the late King breaking their staves of office, throwing them into the grave, and reversing their maces, whilst the king-at-arms, or principal herald, attended by many heralds, cried in a loud, solemn voice over the tomb, "May God show mercy and pity to the soul of the late most penitent and most excellent Charles VI., King of France, our natural and sovereign lord!"

Hardly had these solemn words rolled echoing through the vaulted roof, striking the hearts of the 26,000 spectators with mournful awe, than the herald raised his voice again, and twice demanded their prayers, for the living this time, and not the dead. And thus he cried, "May God grant long life to Henry, by the grace of God King of France and of England, our sovereign lord!"

"LONG LIVE THE KING!"

"LONG LIVE THE KING!"

Then, when an infant ten months old had been proclaimed King over two of the greatest kingdoms in Europe, the sergeants-at-arms and ushers turned their maces, and shouted together, "Long live the King! long live the King!"

The Duke of Bedford was now sole Regent of France, whilst a council of prelates and peers, with the Duke of Gloucester at its head, governed England in the baby King's name, making use of the amusing fiction of issuing all their decrees and mandates as though they were dictated by the mouth of an infant still in arms.

Sometimes Henry misbehaved, or rather showed the natural temper of a baby. In 1423, when his Majesty was nearly two years old, he was taken by his mother to London to hold another Parliament. It was Saturday when they left Windsor, and at night the Queen and her baby King slept at Staines instead of going on. On the Sunday the Queen wished to proceed, and had her son[Pg 270] carried to her car, when, instead of comporting himself with his usual dignity, "he skreeked" (says the quaint chronicler), "he cried, he sprang, and would be carried no further; wherefore they bore him into the inn, and there he abode the Sunday all day. But on the Monday he was borne to his mother's car, he being then merry and full of cheer, and so they came to Kingston, and rested that night. On Tuesday, Queen Katherine brought him to Kennington, on Wednesday to London, and with glad semblance and merry cheer, on his mother's barm [lap] in the car, rode through London to Westminster, and on the morrow was so brought into Parliament." The old historian would make us believe that Henry refused to travel on Sunday, even at two years old.

The guardianship of the baby King had been intrusted to the Earl of Warwick, and in the pictorial history of this Earl he is represented as holding the King, a lovely baby of fourteen months old, in his arms, while he is showing him to the lords around him in Parliament. The Earl, however, only held his sovereign lord on public and state occasions, leaving the young King in his private walks and hours of retirement to the care of a certain Dame Alice Boteler, his governess, and his nurse Joan Astley. "We request," says his infant Majesty, in a quaintly worded document proceeding from his council, but as usual written in his name, and in regal form, "Dame Alice from time to time reasonably to chastise us as the case may require, without being held accountable or molested for the same at another time. The well-beloved Dame Alice, being a very wise and expert person, is to teach us courtesy and nurture, and many things convenient for our royal person to know."

It was whilst Dame Alice was still in power as the King's chastiser that we again find the royal child noticed as holding the opening of Parliament in 1425. Katherine entered the city in a chair of state, with her child sitting on her knee as before. But Henry was now four years old, and no longer needed to be held on Warwick's arm or placed upon his mother's lap. As soon then as he reached the west door of St. Paul's Cathedral, the Protector lifted the child King from his mother's chair, and set him on his feet, whilst the Duke of Exeter, on the other side, conducted him between them to the high altar up the stairs which led to the choir. At the altar the royal boy knelt for a time upon a low bench prepared for him, and was seen to look gravely and sadly on all around him. He was then led into the church-yard, placed upon a fair courser, to the people's great delight, and so conveyed through Cheapside to his residence at Kennington. There he staid with his mother until the 30th of April, when he returned through the city to Westminster in a grand state procession. The little King was again held on his great white horse, and when he arrived at his palace, the Queen seated herself upon the throne of the White Hall where the House of Lords was held, with her child placed upon her knee. This procession drew the people in crowds to see and bless their infant sovereign, whose features they declared were the image of his father.

His tutor, the Earl, was now always with him, whilst his young friends had distinct and separate instructors, for whom reception and entertainment were carefully provided by the Privy Council. Henry's governor, Warwick, was ordered by the King's guardians (speaking, as usual, in the King's person) "to teach us nurture, literature, and languages, and to chastise us from time to time according to his discretion." Unfortunate little Henry! we find more said about his being chastised than about his being rewarded, as if he were of a rebellious and obstinate temper. On the contrary, he was remarkable for his mildness and the meek submission of his character, and we fear the blows which he had to endure only saddened and subdued him, and rendered him unfit to cope with the ambitious and high-spirited nobles who surrounded him.

Little Henry was no sooner eight years old than it was determined by his uncles and his council that he should be crowned King of England in London, and afterward King of France at Paris. So, after much delay, the royal child was taken to Westminster on the 6th of November, 1429, and there crowned with much pomp and state, amongst the acclamations of the people. As soon as the ceremony was over, the little King, in his robes and crown, created, under the direction of his governor, thirty-six Knights of the Bath. Then followed a sumptuous feast in the great Hall of Westminster, where a noble company were assembled, and nobody of note allowed to be absent. Immediately after this, Henry and a great escort of nobles went to Paris, where he was crowned King of France.

His journey to France, his coronation there, the homage and presents he received from French subjects as their King, must often in his after-life have appeared like a dream.

When Henry VI. returned to England he was eleven years old, having been allowed the pleasure of having far more of his own way than he could have obtained in England. Perhaps the ceremony of his coronations, the homage, smiles, and deference shown him, the young companions whose acquaintance could not then be refused, had some exciting influence on his naturally meek and quiet temper. Certain, however, it is that he began at this time to rebel, and demanded from his Privy Council freedom from personal chastisement, which appears to have tried him sorely. The poor boy, however, gained little by his petition, for the Earl addressed the council, and complained that certain officious persons "had stirred up the King against his learning, and spoken to him of divers matters not behoveful," and he begs that he may "have power over any or all of those belonging to his household, and to exchange them for others if he should find it necessary. Also that none be admitted to have speech with the King, except he or some persons appointed be present." He besides besought them to stand by him when the King begins "to grudge and loathe his chastising him for his faults, and to impress their young King with their assent that he be chastised for his defaults or trespasses, and that for awe thereof he forbear to do amiss, and entered the more busily to virtue and to learning."

So Henry, like any other school-boy, submitted, and said no more until he entered on his sixteenth year, when he demanded to be admitted into the council, and to be made acquainted with the affairs of his kingdom. This was granted, and he was after this allowed to conduct his own affairs.

Georgie was a sharp-eyed little fellow still in frocks, who saw everything, and blurted right out what he thought of it. One morning, while he was playing with his toys at his mother's feet, a lady called, bringing with her one of the homeliest little pug-nosed pet dogs that ever lived. Georgie was all attention at once, and his eyes followed Pinkie wherever he went. Presently the little dog came and sat right down before him, and looking straight in his face, wagged his tail, and seemed delighted to see him. Georgie stared at him for a while, and then looked up earnestly into the lady's face, then at the dog, and then at the lady again, as if trying to make out a puzzle. Finally, when he had settled it, out it came. "Mamma," he asked, "hasn't Mrs. Donson dot a nose just like Pinkie's?" and the worst of it was that it was true. Mamma tried to smooth the matter over, but Mrs. Johnson never forgave Georgie.

Everybody has heard of the little girl who, on being asked, after her first visit to an Episcopal church, how she liked the service, replied that it was "all very nice, only[Pg 271] the man preached in his shirt sleeves." That story may or may not be true, but it is true that a little girl in New Jersey said on a similar occasion, "Oh, mamma, the minister had on a long white apron to keep his clothes clean."

Another young church-goer, the daughter of a well-known Baptist clergyman in Brooklyn, who was a critic in her way, and who had a faint suspicion that anecdotes generally were "made up" for the occasion, went one day with her father to hear his Thanksgiving sermon. He told a melting story about his poor blind brother who, notwithstanding his infirmity, was always cheerful and happy. The audience was deeply impressed, and many, including the speaker himself, were moved to tears. On her return home, Mary, we will call her, said, with deep earnestness, "Papa, when you were telling that about Uncle Nat this morning, did you say the real truth, or were you only preaching?"

A four-year-old Sunday-school girl did the best she could with a question that was asked of the infant class. Said the teacher, reading from Isaiah, xxxvii. 1: "'And it came to pass, when King Hezekiah heard it that he rent his clothes.' Now what does that mean, children—he rent his clothes?" Up went a little hand. "Well, if you know, tell us."

"Please, ma'am," said the child, timidly, "I s'pose he hired 'em out." (This is an actual fact, and the name of the town where it occurred begins with "M.")

A pretty anecdote is told of a little girl to whom the unseen world is very real. "Where does God live, mamma?" she asked, one evening, after saying her prayers.

"He lives in heaven, my dear, in the Celestial City whose streets are paved with gold."

"Oh yes, I know that, mamma," she said, with great solemnity; "but what's His number?"

Doubtless she expected to go there one day, and wanted to make sure of finding the way.

"How does the Lord make cats?" asked an inquisitive little fellow, who was always trying to find out the whys and wherefores of things. "Does He make the cats first, and sew the tails on, or does He make the tails first, and sew the cats on?" Every clergyman who comes to the house is asked the same question, but no satisfactory reply has yet been given. He threatens now that unless he finds out very soon, he will take his favorite Topsy all to pieces, and see for himself.

A little girl in Oil City is just recovering from a severe attack of scarlet fever. During her illness she has been greatly petted by her indulgent parents, who bought her any number of toys and nice things. A few days ago, as she was sitting up, she said, "Mamma, I believe I'll ask papa to buy me a baby carriage for my doll." The brother—a precocious youngster of only six years of age, spoke up at once, and said, "I would advise you to strike him for it right away, then; you won't get it when you get well."

A little girl went timidly into a store at Bellaire, Ohio, the other morning, and asked the clerk how many shoe-strings she could get for five cents.

"How long do you want them?" he asked.

"I want them to keep," was the answer, in a tone of slight surprise.

It was just after Christmas, and Kenneth's mind was full of the story of the Babe who was born at Bethlehem. When, therefore, he was taken into mamma's room to see his new little brother, he looked with wonder on the dainty cradle, trimmed with lace and ribbons, wherein the little baby lay, and asked, in an awed whisper, "Mamma, is that a manger?"

A neighbor asked a little girl the other day if her father wasn't one of the pillars of the Miamus M. E. Church. "No, indeed," she warmly replied; "they don't have any pillows there."

When in budding trees

Bluebirds sweetly sing,

And the pretty early flowers

Come to welcome spring,

"No more cold," we think,

"No more sleety rain";

But sometimes old Winter turns,

Mocking, back again.

Then the bluebirds hide,

And the buds stand still,

And the flowers droop and shrink

With a sudden chill,

And the young vines stop

Growing in the wood,

Waiting patiently until

He is gone for good.

But when, some fine night,

In a friendly throng,

From the swampy places where

They have slept so long

Hop the frogs, and all

Loudly croak together,

Then there will be, we are sure,

No more wintry weather;

And the birds rejoice,

And the buds unfold,

And the sun upon the grass

Lies in bars of gold.

Now I'd like to know,

For it's surely so,

How when spring is really here

Frog-folks chance to know.

The only European species of the antelope family are the chamois (Antelope rupicapra), which inhabit the highest regions of the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the Caucasus. On inaccessible cliffs and rocky crags these graceful mountaineers make their home, and except when disturbed by the approach of man, lead a peaceful and harmless life. The chamois resembles the wild goat of the Alps, but is more elastic and spry. It is especially distinguished from it by the absence of beard, and by its black glistening horns, which are curved like a hook and pointed.

In the spring the chamois is very light-colored, but as summer advances, its coat assumes a reddish-brown hue, which by December often becomes coal black. Its eyes are large, black, and full of intelligence, and its delicate hoofs are surrounded by a projecting rim which renders it firm-footed and able to march with ease over the great glaciers or along narrow ledges of rock.

These pretty animals live in herds, five, ten, and sometimes twenty together. They are merry, wise creatures, graceful and agile in their movements, and spring from cliff to cliff and across chasms with extraordinary lightness and sureness of foot.

In the winter the chamois seek the upper forests on the mountain slopes, where, under the shelter of the widely branching umbrella fir, the drooping boughs of which hang almost to the ground, they find snug quarters, and long dry grass for winter provender.

The opening of spring in the Swiss Alps is attended by many wonderful phenomena. It would seem that no power was strong enough to break the icy chain in which the high Alps are bound fast; but there comes a day, generally[Pg 272] early in April, when beautifully tinted veils of cloud form over the southern horizon, and a death-like stillness prevails in the mountains. The eye of the experienced hunter detects this sign in a moment, and knows it to be the token of approaching danger. If among the glaciers, he hastens to the valley below, where he finds the villages in commotion. Sheep and cattle are being hurriedly housed, and everything being secured against the dreaded Föhn, which is surely coming from beyond those rose-tinted clouds in the south. The Föhn is a warm wind which, in the spring, comes blowing northward from the hot African desert. On a sudden the stillness is broken by a terrible rushing sound, and a burning breath like fire strikes on the snowy pinnacles and glaciers. All nature is soon in an uproar. Mighty banks of snow, loosened from their winter resting-place, roar and rumble down the mountain-side in avalanches, bearing huge rocks and giant trees in their arms. The whole winter architecture of the mountains crumbles to ruins before the burning desert wind.

BATTLE OF THE CHAMOIS.

BATTLE OF THE CHAMOIS.

When the storm is over the great ice beds and banks of snow cease their pranks, and peace reigns once more in the mountains. But the strength of winter is broken. The Föhn returns again and again, and soon patches of bluish-green begin to appear here and there among the high precipitous crags. When the highest mountain pastures are open, the chamois leave their forest retreat, and troop upward into the most lofty regions. Here they lead a happy life. They are most frolicsome in the autumn, and may be seen for hours together gambolling and chasing each other upon the very smallest ledges of rock, where it would seem almost impossible to maintain a foothold. There are sometimes bitter fights, too, between the male chamois, terrible contests for leadership. Grappling each other with their horns, they battle until the superiority of strength is decided.

The chamois is very shy, and is always on the alert. Its sense of hearing, of smell, and of sight is very acute, and the most skillful hunter will sometimes search the mountain pastures for days without securing his game. When the troop is grazing, a sentinel is always appointed, who stands on the watch sniffing the air. At the least approach of danger the careful sentinel gives a shrill whistling signal of warning, and instantly the troop is filing off between the rocks and along the chasms, where no human foot could follow, all whistling together as they march. The only chance of the hunter to escape detection by these watchful creatures is to approach them from above, for, as if conscious that there are few so daring as to penetrate the upper regions of eternal snow, the sharp eye of the sentinel is on the look-out for danger from below.

As the greatest skill and courage are required to secure this valuable game, a good chamois-hunter is a person of importance in the wild Swiss valley where he lives, and the family of which he is a member glory in his deeds, and relate them to awe-struck listeners around the evening fireside. Chamois-hunting is the central point around which cluster all the charms of romance and dangerous adventure; it is the subject of many popular ballads, and its hold upon the imagination of the people is wonderful. Chamois skulls adorned with the black hooked horns may be seen among the most precious treasures of many a Swiss household, each one suggestive of some tale of wonderful bravery and endurance.

The chamois-hunters of Switzerland lead a strange life. None knows when he departs from his home in the morning with his gun, ammunition, and alpen-stock, if he will ever return from the mysterious misty heights towering before him far aloft in the clouds. The pursuit of the chamois will often lead him to the narrowest boundaries between life and death, to overhanging cliffs, and across gorges where even the falling of a bit of turf or the loosening of a stone would be fatal. Up, up, the hunter must go in search of the cunning game, until lost among the cliffs, and blinded by the thick mists which appear as clouds to those in the valley below, he may often wander in the trackless solitudes for days, with the terrible roar of avalanches sounding in his ears, before being able to return to his home. And yet in face of all these dangers, the Swiss, apart from the price they obtain for the flesh, skin, and horns of the chamois, have an inborn love of this sport, and stories are told of many celebrated hunters, men to whom every rock, tree, and path on the high mountains was as familiar as the streets of their native village, and who feared neither fogs, snowstorms, nor avalanches. But few of these hunters, however, have died at home in their beds, for in the end accident overtook them, and their lofty hunting ground became their grave.[Pg 273]

To the Indians of the great Western plains the red willow, which is only found in that country, proves so very useful that its loss would be greatly felt by them. It is a bushy growth, never reaching more than fifteen or twenty feet in height, and is found along the river-banks, where it grows rapidly and in great abundance.

The Indian most values the red willow because from its bark he makes what to him is a very good substitute for tobacco. To do this he strips one of the long, slender shoots of its leaves, and with his knife cuts the bark until it hangs from the wood in little shreds. Then he thrusts the stick into the fire, but not so that it will burn, only so that the bark will become thoroughly dried. When this is done, he carefully rubs it between his hands until it is crumbled almost to a powder.

This willow-bark powder he mixes with a small quantity of real tobacco, if he has any; if not, he mixes it with the dried and crumbled leaf of a small and very bitter shrub that grows on the mountain-sides, and has a leaf looking somewhat like our box-wood. The Indians call it killicanick, and often mix it with tobacco when they have no red willow. So fond are the Indians of their red-willow tobacco that they prefer it to the real unmixed article, which seems to be too strong for them.

The squaws use the red willow to make temporary shelters or wick-i-ups, which are used instead of the heavy skin lodges, or tepees, when the Indians are on the move, and only camp in one place for a night or so.

When a pleasant spot by some running stream, where there is plenty of red willow, has been fixed upon for a camping-place, and a fire has been lighted, the squaws cut a quantity of the willow, and, making a rude framework of the larger branches, of which the butt-ends are fixed firmly into the ground, and the small ends bound together to look like a small dome, they weave the smaller branches and twigs in and out until the whole affair looks like a great leafy basket turned upside down. The entrance is very low, and when once inside, a grown person can only lie or sit down, for if he should stand up, he would probably lift the house with him.

While the squaws are building the wick-i-ups the Indian has been stretched on the ground, smoking his long-stemmed pipe, with its stone or iron bowl, or else he has been kneeling beside the fire preparing his much-loved red-willow tobacco. Over the same fire is hung a jack rabbit, skinned, and spitted upon a slender red-willow stick, and from a tree near by the baby swings in his red-willow cradle.

From the same red willow the squaws make baskets and mats. On its tender twigs the ponies browse in winter, when the grass is covered deep with snow. And to these same red-willow thickets the Indians go in winter in search of deer or antelope, which are pretty sure to be found browsing among them.

So you see the Indian has good reason to be fond of the red willow, and he dreads the approach of white farmers, who clear it off from the rich bottom-lands wherever they locate, for it is on these lands that they can raise their heaviest crops of corn.

Six tow heads bobbing about a pen in the big barn. In the pen were thirteen small pigs, all squealing as only small pigs know how to squeal.

The owners of two of the tow heads soon departed. They were Solomon and Isaac. Being fourteen years old, they were too ancient to care much for pigs. Elias and John also went away. They had business elsewhere[Pg 274] in the shape of woodchuck traps. Philemon would fain have lingered near, had he not made an engagement to play "two old cat" with Tom Tadgers.

As for Romeo Augustus, no charm of bat or ball would have drawn him from that pen, since he had seen one of the small pigs stagger about in a strange fashion, and then sink down in a corner. Something was wrong with that pig.

Romeo Augustus peered and peeped. At last into the pen he climbed, and caught the little pig in his arms.

Then there was a hubbub indeed. Up rushed the mother in terrible excitement. Round and round spun the twelve brothers and sisters, each crying, "No, no, no, no," in a voice as fine as a knitting-needle, and as sharp as a razor edge.

But Romeo Augustus kept a steady head. Back over the pen he scrambled, pig and all, and sat down on the barn floor to find out the trouble.

Ah! here was enough to make any pig stagger. Two little legs dangled helplessly—one fore-leg, one hind-leg. The bones were broken.

At first Romeo Augustus was tempted to weep. What good would that do? It was far better to coax the bones into place, put sticks up and down for splints, and bind one leg tight with his neck-tie, the other with his very best pocket-handkerchief.

It was not an easy job. The pig did writhe and twist, while the frantic mother danced up and down in the pen behind, and drove the surgeon nearly crazy with her noise. But he toiled bravely on, and when at last the operation was done, the heart of Romeo Augustus was knit unto that small pig in bonds of deep affection.

"I love him as if he was my—daughter," said Romeo Augustus, solemnly. He did not confide this to his twin brother Philemon: Philemon would have jeered. He told it to Elias, who was poetical, and had a soul for sentiment. Elias nodded, and said,

"Just so!" That showed sympathy. He also added, "Why don't you keep him for your own, and call him Leggit or Bones?"

"No," answered Romeo Augustus, with dignity; "his name shall be Mephibosheth, for the man who followed King David, and was lame in both his feet."

For five weeks Romeo Augustus nursed and fed and tended that pig. In time the legs grew strong. Mephibosheth was as brisk as any pig need be. Romeo Augustus rejoiced over him, and loved him more and more. So the days went on, until a certain morning dawned.

The sun rose as usual; the cocks crowed as cheerfully as they always did. Solomon and Isaac had gone to drive the cows to pasture, as was their wont. Elias and John were peacefully skinning their woodchucks in the shed. Philemon had been sent back to his chamber (as he was every morning of his life) to brush his back hair. There was nothing to suggest the storm which was to break over Romeo Augustus, who stood by the kitchen stove watching the cook fry fritters.

"Fizz, fiz-z-z, fiz-z-z," hissed the fritters.

"Aren't they going to be good!" said Romeo Augustus, smacking his lips.

Suddenly came a voice. It was Romeo Augustus's father speaking to the man-servant:

"Those little pigs are large enough to be killed. How many are there? Never mind. Carry them all to market to-morrow, and sell them for what they will bring. I don't want the trouble of raising them."

Romeo Augustus listened in horror. "Large enough to be killed?" "Carry them all to market?" "All? All?" Why, that included Mephibosheth. Terrible thought!

Not a fritter did Romeo Augustus eat that morning. After breakfast he roamed aimlessly about the farm. He would not go near the barn. How could he look upon poor doomed Mephibosheth?

Once he thought of going to his father, and pleading with him for his pig's life. But Romeo Augustus was shy, and somewhat afraid of his father, who was a stern man. So he kept his grief to himself, and meditated.

Elias unconsciously deserted him at this time of need, and curdled Romeo Augustus's blood by asking twice for pork at dinner. Ask for pork? Why, speaking coarsely, Mephibosheth was also—pork. How could any one eat pork with such a relish? Romeo Augustus shivered, and kept his own counsel. All that afternoon he pondered. Then the darkness of night came on.

The next morning off started the man-servant with his load of little pigs.

"Have you all?" asked Romeo Augustus's father.

"I would ha' swore, sir, there was thirteen, but it seems there was only twilve. Yes, sir, I has 'em all;" and away he drove.

As for Romeo Augustus, a change came over him. Far from shunning the barn, he hung about it constantly. Moreover, he was always present when the cows were milked, morning and night. He had a playful trick of dipping his own tin cup into the foaming pail, and scampering away with it full to the brim. Nobody objected to that. If he chose to strain a point, and drink unstrained milk, he was welcome to do it.

"And if you see fit to save half your dinner, and give it away, I am willing," said his mother, who was busy, and hardly noticed what Romeo Augustus asked her. "But you must not soil your jacket fronts as you do. This is the fifth time within a week I have sponged your clothes."

Soon after this, Philemon and Romeo Augustus were out in the barn, rolling over and over, burying themselves in the sweet-smelling hay.

Suddenly Philemon pricked up his ears.

"What's that?" quoth he. "I heard a little pig squealing. Where can he be?"

"Philemon," said Romeo Augustus, earnestly, "let's climb to that top mow, and jump down. Hurrah! It's a good twenty feet. Come on, if you dare!"

If he dare! Of course he dared. It was great fun to launch one's self into space, and come whirling down on the hay. There was just enough danger of breaking one's neck to give spice to the treat. How Romeo Augustus did scurry about, hustling Philemon whenever he stopped to breathe, and urging him on, shouting at the top of his lungs,

"One more jump, old boy. Hurrah! Hurray!"

Philemon had no spare time in which to wonder if he heard a small pig squeal.

That very night, when all the family was wrapped in slumber, Elias felt a hand on his shoulder. Another hand was on his mouth, to prevent any exclamation.

"Come with me," whispered Romeo Augustus; and he held out Elias's jacket and trousers. Elias took the hint, also the clothes. Down the stairs crept the two. Out the front door, which would creak, into the moon-lit yard stole they. Elias's eyes were snapping with excitement; for, as I said, Elias was poetical, and, like all poets, he was always expecting something to turn up. At this present he was on the look-out for what he called "the Gibbage."

Elias himself had grown to believe the marvellous stories he told his brothers. He had full faith in the Lovely Lily Lady, who lived in the attic; in the Mealy family, with their sky-blue faces and pea-green hands, in the cobwebby meal chest under the barn eaves; in the Peely family, who inhabited the tool-box in the shed, and whose heads were like baked apples with the peel taken off; in the big black bird, which came from the closet under the stairs at night, and flew through the chambers to dust the boys' clothes with its wings.

And now Elias had suspected in his own mind that there existed a creature, somewhat like a mouse, somewhat[Pg 275] like a red flower-pot, which glided around during the night-watches to sharpen slate-pencils, smooth out dog-ears from school-books, erase lead-pencil marks, polish up marbles, straighten kite strings, put the "suck" into brick-suckers, and otherwise make itself useful. If there were not such a creature, there ought to be, and Elias became daily surer that there was. He called it "the Gibbage."

Perchance Romeo Augustus had caught a glimpse of it. No wonder Elias's eyes snapped as he was hurried across the yard, and led back of the barn, where there was a space between the underpinning and the ground. By lying flat one could wriggle his way under the barn, and when once beneath, there was room to stand nearly up-right.

"Elias," said Romeo Augustus, breathlessly, "I keep Mephibosheth under here."

"Sakes and daisies!" gasped Elias.

That was a very strong expression. When somewhat moved, Elias often exclaimed, "Sakes!" but when he added, "and daisies!" it was a sign he was stirred to his inmost depths.

"Sakes and daisies!" said Elias.

"Yes," Romeo Augustus went on, "I heard father say he didn't want the trouble of raising him, so I concluded I would. But nobody must see him till he's raised, and Philemon he heard him this very day. I must take him somewhere else. Where, Elias, oh, where can I carry him?"

Elias frowned and pondered. He was grieved not to have discovered "the Gibbage," but he would do the handsome thing by Romeo Augustus.

Half an hour later the jolly old moon nearly fell out of the sky for laughing. There were Elias and Romeo Augustus straining and tugging, coaxing and scolding, trying with might and main to stifle the expostulations of Mephibosheth, as they bore him down to an unmowed meadow.

The ox-eye daisies opened their sleepy petals to see what all the stir was about. The buttercups and dandelions craned themselves forward to peep.

Down in the meadow the boys drove a stake, and to it they fastened Mephibosheth. It was no joke taking food to him now. The unmowed meadow was in sight of the house, and it seemed as if one or another of the boys was always at the window. But Elias aided Romeo Augustus, and between them Mephibosheth got his daily rations. Surely he was safe at last. Far from it.

"Who has been trampling the grass in the north pasture?" asked Romeo Augustus's father, a fortnight later. "I followed the path made by feet that had no right there. At the end I found a stake. Tied to the stake I found a—"

Solomon and Isaac looked surprised. John and Philemon shook their heads. They knew nothing of the matter. Elias and Romeo Augustus quaked.

"At the end I found a—" repeated their father, gazing sternly round the table—"I found a—"

"Pig," said Romeo Augustus, in the smallest possible voice; and he fled from the table in an agony of tears. His labor had been in vain. After all, Mephibosheth must die. How could he endure it? He dared not glance out of the window of the chamber where he had taken refuge, lest he should behold Mephibosheth led to slaughter. It seemed as if his heart would break in two.

But listen! What is that noise? A clatter as of falling boards. There is a sound as of hammering. At first it seems to Romeo Augustus like Mephibosheth's death-knell. Thud, thud, thud, go the blows. Drawn almost against his will, Romeo Augustus stealthily approaches the window. He glances fearfully out. What does he see? His father pounding busily, making—what is he making? Can it be? It is—it is a pen.

"Father!" gasps Romeo Augustus.

His father looks up and smiles. "Your pig must have a house to live in," says he. "I can't have my meadow grass trampled."

Before noon Mephibosheth was in his new quarters. There was a parlor with two pieces of carpet on the floor; there was a chamber with plenty of straw, whereon Mephibosheth could repose; there was a dining-room, with what, in common language, might be termed a trough.

Such a life as that pig led! He was cared for tenderly. He was washed all over every morning, and put to bed every night. He was not a very brilliant pig as far as his intellect went, it must be confessed. He could do no tricks with cards; he could not be taught to jump through a hoop.

One year passed; Mephibosheth was large. Two years went by; Mephibosheth was wonderful. I would I could say he was plump; that word does not begin to express his condition. It would be pleasant to call him stout; that would not give the glimmer of an idea of his size. Corpulent would be a refined way of stating it. Alas! corpulent means nothing as far as Mephibosheth is concerned. That animal measured seven feet and twenty-two inches round his body. He weighed—truth is great, and must be spoken—he weighed five hundred and fifty and two-third pounds.

He could not walk; his legs were pipe-stems under him. He could scarcely breathe. That is the excuse for what happened.

One day Romeo Augustus came home from school. Mephibosheth's pen was empty. Mephibosheth's pen would be empty for evermore. That is a gentle way of telling the story. In vain it was explained to Romeo Augustus that Mephibosheth's life had become a burden; that common humanity demanded his departure. In vain Philemon offered three fish-hooks and a jackknife by way of solace. In vain Solomon was sure his father would present a calf to the mourner for a pet.

Elias was the only one who gave the least comfort.

"We will make a tombstone, and I will write an epitaph," said he.

Soon he brought a board, on which were drawn an urn and a couple of consumptive weeping-willows (for Elias was an artist as well as a poet), and underneath were these lines, which being written partly in old English spelling, were so much the more consoling:

Sacred to the Memorie

of

MEPHIBOSHETH.

Kinde Reader, pause and drop a teare,

Ye Pig his bodie lieth here;

Ye Auguste third of fiftie-nine

Was when his sun dyd cease to shine.

He broke two legs, which gave him wo;

He doctored was by Romeo,

Who cherished him from yeare to yeare,

As by this notice doth appeare.

He fed him till he waxed soe big

He was obliged to hop the twig.

Ye friends do sadly raise their waile,

And fondly eke preserve his tayle.

"And here's his tail," said Elias, presenting the pathetic memento.

"The only trouble is in the line, 'Ye Pig his bodie lieth here,'" sobbed Romeo Augustus. "It doesn't lie here. He's been sold to a butcher."

"It's Elias who 'lieth here,'" remarked Isaac.

That was a heartless joke. No one was so low as to laugh at it.

"They often have monuments without the—the—the body," said Elias, with great delicacy.

Romeo Augustus was content.

He is a grown man now, but to this very day he keeps Mephibosheth's monument. It is nailed on the wall of his chamber. He sometimes smiles when he looks at it, but he does not take it down.[Pg 276]

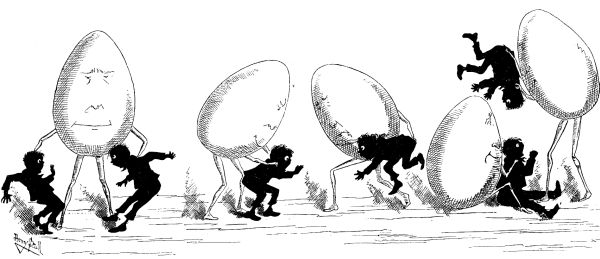

HAVING A LITTLE FUN.

HAVING A LITTLE FUN.

Ever so long ago there lived a tailor's apprentice, a merry, light-hearted fellow, but with a large hump, so that he always looked like a country-woman going to market on a Saturday, carrying her goods on her back.

One night, as he was returning from some festivity in the town, he had to go through a thick wood, in which it was so dark that he could not see his hand before his face. As he was dawdling along quite merrily, and whistling the tune of the last waltz that he had danced, he lost his way, and fell into a deep pit, so that sight and hearing forsook him, and he gave himself up for lost. But when he found out that he was unhurt after the fall, he began to cry pitiably and to call for help, till he suddenly heard talking not far off.

In the pit, which sloped sideways far down into the earth, lived a large wolf with his wife and two little ones, and when they had heard the tailor's fall and screams, the old wolf said, joyfully, to his wife,

"Be quick, my dear, hang the pot over the fire; I think we shall have something good to-night."

These words reached the ears of the tailor, who, in the deepest anxiety for his life, became as still as a mouse.

But the wolf opened the door of his den, put a lamp in his paw, and peered all round till he had discovered the tailor, whom he then seized by the legs, and, without more ado, dragged into his sitting-room.

When he was about to be killed, the poor fellow cried and bemoaned himself in such a heart-rending manner that the wife, who was a good soul, put in a word for him to her husband.

"Well, then," said the wolf, "he may live, but he must never return to men, or he would betray us; he must stay here and become a wolf."

"Most joyfully," said the tailor, "for I would rather live as a wolf than be cooked and eaten as a man."

Whereupon the wolf fetched one of his old furs out of the cupboard, and his wife had to sew the tailor into it.

So the tailor staid with them, soon learned to howl perfectly, and to walk on all fours; besides which, he became quite expert in catching rabbits.

One day, when they had all gone out hunting together, it happened that the King of the same land was also hunting in the wood. As soon as the hunters came near the wolves, they and the tailor took to their heels.

They ran into a neighboring thicket, and hid themselves behind some bushes, when the old wolf whispered to the others to keep quiet, without fear, for he had seen no dogs, and without their help no huntsmen would find them.

He spoke truly, for it so happened that a wild boar had killed every single dog.

Then it occurred to the King to take a pinch of snuff; after which he sneezed violently.

The tailor, who had not yet lost his knowledge of polite ways, said, respectfully, "Your health, sire!"

When the King heard these words he rode toward the bush, and all his huntsmen followed him.

Here they perceived the wolves, and the King and his companions set up a loud shout of joy. They threw their spears so well that only the old wolf could escape; and the tailor was the last to be seen, because he had hidden himself so well, but before the huntsmen could aim at him, he had rolled himself, howling piteously, toward the King, saying,

"I beg your pardon, sire; I am really a tailor's apprentice, and only by accident among the wolves."

Then they all began to laugh, and a huntsman cut him out of his skin. A horse also was brought, that he might ride by the King's side and relate his tale.

"Tailor," then said the King, very graciously, "you have caused me much amusement, and if you like you may remain with me."

This speech pleased the little man right well, and he rode straight away to the castle, where he lived in joy and luxury for some time, as the King's court and private tailor.

But the old wolf, who had escaped with his life, felt raging anger against all human beings, especially toward the tailor, who had been the cause of the death of his wife and children, and he determined to revenge himself.

So he lay continually on the watch, and any man who appeared in his sight was a child of death. The whole land was full of grief and sorrow, for hardly a day passed[Pg 277] in which at least one human being did not meet with a sorrowful end in the grip of the fierce old wolf.

But he said, "It is not yet enough; they must all come to it; and the tailor shall suffer the most for bringing about the death of my wife and children, because he could not hold his tongue."

Saying which he went to the castle, where the tailor was just looking out of the window smoking a pipe.

"Fellow!" said the wolf, "you must die, or I can not rest."

Terror seized the little man, and he told the King what the wolf had threatened.

"Wait, tailor," answered the King; "it is now high time that we should catch this wretch, even if it costs me my only daughter. He has not even respect for the court tailor; so what will such conduct lead to? And besides, he is eating up all my subjects, which I can not allow; for if I have no subjects, I can no longer be a king."

He spoke, and caused it to be proclaimed through the whole land that he who brought the wolf alive should be his son-in-law.

The tailor had not dared to leave the castle for days, for fear of the monster; but at length he could sit still no longer, and went into the garden one bright summer's day. Suddenly the wolf sprang from behind a tree, caught the poor fellow by the tail of his coat, and dragged him far into the wood, in spite of all his wriggling and screaming.

"Rascal of a tailor!" said he; "you have brought me into misery, therefore you must die."

Then, in his dire need, a cunning, artful idea occurred to the tailor, and he exclaimed, "Look! there come the huntsmen!" and as the wolf turned round in alarm, the tailor leaped on to his back, and held his hands tightly over the creature's eyes.

Then the wolf ran as he had never run in his life before, so that each moment he thought his hated rider must fall to the ground.

And as the creature could not see, the tailor guided him toward the castle, to an open stable door; there got down, pushed him into one of the stalls, and then bolted the door on the outside.

The King was highly delighted that the tailor was such a cunning fellow, and consented that the betrothal to his daughter should take place at once.

The wolf was hanged, and his skin, which the tailor received among his wedding gifts, has been preserved to the present day, and just now lies under the table, belonging to the author of this little tale.

AN EASTER EGG.

AN EASTER EGG.

There was a rat lived in a mill—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill;

If she's not dead, she lives there still—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

This rat she had a great long tail—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill;

One day she caught it on a nail—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

She pulled so hard she pulled it out—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill;

And then she turned herself about—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

At home I've got a little babee—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill;

I wonder if she will know me—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

Oh, mother! mother! where's your tail?—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

Yonder it hangs upon a nail—

Heigh oh! says Tidley Pill.

[Pg 278]

It gives us the greatest pleasure to receive all the pretty favors which come to us by every mail from all parts of the country. Those communications which we think will be of interest to other children we print whenever we can make space for them, and all, without any exception, are carefully read, and their receipt acknowledged. These letters give pleasant, satisfactory glimpses into many homes, and we see the group of eager young faces watching, as they tell us, "for papa to bring our paper." Do not be disappointed, any of you, when you fail to find your pretty letter, which you have written so carefully and neatly, printed in the Post-office Box. We can not print all. If we did, you would have no stories to read, no pictures to look at—nothing but letters; for your busy little brains and fingers would fill the whole paper every week if we did not crowd some of you out. But keep on writing, for we like to hear what stories please you best, and in what subjects you are most interested. In that way there is always a mutual understanding between us, and our acquaintance is more likely to be intimate and lasting. We are also very much interested in what children write about the seasons in different regions of the country, showing how spring advances from Texas up into the far northern State of Oregon. Such letters are always interesting and instructive. One request we would make, that is, always write your signature very distinctly. Often we can not make out even your initials, and your name may be misprinted in our acknowledgments.

Warren, Ohio, March 1, 1880.

The robins and the bluebirds came here about the middle of February, and if it does not get colder, willow "pussies" will be out in a few days. Please tell me what the "wind-flower" is. I do not think, as Bertie Brown does, that people ought to send the Indians something to eat, for mamma had an uncle who lived in Minnesota, and he used to feed them whenever they came, and they killed him and three of his children. So I don't like Indians.

D. J. Myers.

The wind-flower is found in the early spring growing among dry leaves and in sunny nooks by old stone walls, sometimes in open pasture lands where the soil is damp. The blossoms, which are pale pinkish-white, grow on a stem from two to four inches in height. There is only one drooping flower on a stem. This plant is more properly called anemone, from anemos, a Greek word signifying wind. It is interesting to know that it was called anemone by the ancient Romans. Pliny alludes to it, and says it was called wind-flower because it opened its petals only when the wind blew.

Fairfield, Alabama.

My heart is gladdened once a week when papa says, "Daughter, here is your paper." I am far away in the South, but Uncle Sam's mail arrangement is so grand that it finds us all. I was eleven years old last month, and had a nice birthday party. I go to school, and love my teacher very much.

Mamie Jones.

Atlanta, Georgia.

I have lived in the South two years, although I was born in Ohio. There is never any snow here, and I long to get back North on account of winter sports. Atlanta is surrounded by beautiful scenery, and also by many traces of the war, such as intrenchments and breastworks. In answer to Edwin A. H., I will say that I have a cabinet, but have not so many specimens as he. I have minerals and other things from many parts of the far West, collected by myself, and also dried flowers from New Zealand, and a nut from Vancouver Island.

John G. Wilson.

Monmouth, Oregon.

I thought I would drop a line to you, and let you know that I am one of the readers of Young People. I like it very much. I am nine years old. I have a little brother who has some pet rabbits. I left Wales with papa and mamma when I was three years old. Then I could not speak a word of English, but now I don't remember a word of Welsh. We are having lots of snow here this winter.

David Foulkes.

Wrightstown, Pennsylvania.

I live in a very quiet little village. Just across one field from our house stands a house which was Washington's head-quarters at the time of the Revolutionary war. About one-quarter of a mile away there is a tree, more than a century old, under which Washington stood just before he started for Trenton on Christmas-night, 1776. He crossed the Delaware six miles east of this place. Near this village is a barn two hundred years old.

Rose W. Scott.

Erie, Pennsylvania, March 3, 1880.

About five weeks ago a lady in this place found two pansies in bloom in her garden, and last week a man told my papa he saw a large flock of robins in some cherry-trees in his yard. If they were looking for cherries, they were disappointed. Had they come into our yard, they would have seen a large bed of bright yellow crocuses. I am eight years old.

Carrie L. Willard.

Jacksonville, Florida.

In Young People No. 13 Joseph P. writes that he hatched a chicken by putting the egg in ashes. I tried it. I put the egg in a tobacco-box, and put it by the stove. Mamma's servant built a hot fire, and the egg, instead of hatching, baked.

Eddie E. Paddock (8 years).

Petersburg, Indiana.

I am a little girl seven years old, and I live on a farm with my grandpa and grandma. My dear mamma died last December. It was very hard to part with her, but I am not destitute of friends. I have three uncles, who are very kind to me. I have a little canary-bird. He is a beautiful singer, and is company for me. And I have a large dog that plays with me every day. I call him Watch. I can read in the Third Reader, although I never went to school but one week in my life, on account of ill health. I have had the chills for five years—not all the time, but very severe.

Anna Shandy.

Answers to S. R. W.—including, however, no new words—are received from Polly Pleasant, Ethel S. M., Herbert W., Mamie E. F., Maud Chase, F. E. Bacon, B. E. S., Connie, Frank N. Dodd, Carrie S. Levéy, R. W. Dawson, "School-Children," C. B. F.

Salem, North Carolina.

Mamma takes Young People for me, and I like it very much. I made a Soapboxticon to-day, and had trouble with it at first, but now it works nicely. I hope all who try to make one will succeed as well as I did.

A. H. Patterson.

George F. Powers, Willie G. Lee, Frank Shennen, M. Paul Martin, and Fred A. Conklin report trouble with the Soapboxticon, but if they persevere, and carefully follow directions, they will soon have a pretty toy.

Athens, Alabama.

I must tell you how I enjoy Young People. My good uncle Henry takes it for me. I must tell about my pet geese. Their names are Boss and Susan. They are very gentle, and as smart as they can be. I have a puppy named Bang-up. My grandpa named him. I am six years old, and my mamma is writing this for me.

William S. Peebles.

Evans Mills, New York.

Can any one tell me who is the oldest man in the United States?

Madison Cooper.

Who among our young correspondents can answer this question?

Chelton Mills, Pennsylvania.

I have a bird named Cherry, and a dog named Jack; and I have a little sister named Mae, and she is so cute. She has a doll, and she nurses her so sweetly! I am eight years old, and I go to school. We have heard robins and bluebirds singing.

Ellie Carle.

Belle Plaine, Minnesota.

My kitty comes to my room every morning, and jumps upon my bed. His name is Jim. He is a nice kitty, and full of play. He scratches me sometimes awful hard, but I love him all the same. I saw a picture in Young People of a little girl and her kitty.

Elvira F. Irwin.

Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

I have a canary named Frank. He used to bite my nose and fingers when I put them in his cage, but he will not bite them now. I also have a small turtle, whose shell is about two inches long. It came from the Niagara River. It sleeps in winter, excepting when the sun shines on it, and it will not eat. But in summer it eats flies and bits of raw meat.

Florence E. M.

Denver, Colorado.

I have no pets to write about, but I expect to have a Newfoundland dog soon. We live in a new house, and do not need a cat; but when the rats come, we are going to get one. I have thirteen dolls. The largest one has black hair and gray eyes, and her name is Josephine. I am nine years old.

Sadie T.

Waltham, Massachusetts.

I am seven years old. I have no brothers or sisters, but I have a squirrel and a fish. The squirrel was caught after he made his home in the woods, and he was so wild that he would bite if we touched him; but we were so kind to him that he begins to feel better. We let him out now, and he runs round the room, and I can put my hand on him. My fish is the last of three. The other two started to go back to their native river one night, and they fell on the floor and were killed.

Frankie L. Whitney.

John B. M., Nicholas P. G., and Robbie C. write pretty stories of their pet cats, dogs, and foxes, which we regret having no room to print. In answer to Robbie's question, we would say that the bite of a fox is painful, but not dangerous like that of a dog.

Willie R. C.—When you recover from your illness, and can write your "own self," we will print your letter if it is interesting.

Loudon Engle and Harry D.—Pigeons like to eat bird seed, broken corn, or any kind of grain, and enjoy that kind of food much better than bread-crumbs. They need fresh water to drink, and will bathe now and then, like a canary, if they have a bath dish large enough to flutter in.

W. M. L.—There is many a one much older than you who would be glad to know an easy and quick way to make ten dollars. Unfortunately we can not tell you how to accomplish your object.

Meta.—Your poetic idea of beauty is very pretty, and shows much imagination for such a little girl.

Bessie D. L.—Call your bird Rosie, and your kitty Clover. There was once a big Maltese cat named Clover who did many funny tricks, and lived to be very old. If you name your kitty after her, perhaps she will live as long.

Mary B.—Your plan for a picture scrap-book is very good. Try to select some pictures of historical localities and celebrated buildings, and then, when you show your book to your little friends, you will have something interesting to tell them.

Clara M. H.—Your "old bachelor uncle" is very kind to send you Young People, and you will be glad to hear that a large number of other uncles have made their little nieces happy in the same way.

Favors are received from H. M. H., John V. Gould, Alfred D. S., W. E. Liddy, Fannie Spencer, Grace Field, P. S. Heffleman, Alice Maud T., Beatrice W., Margaret Baird, Elva E. Groat, Eugene Lewis, Lucy Cole, May and Josie Minton, Gertie Harrison, Ella E. Ball, George Kohler, Fred Castle, Annie P., H. S. Richardson, "Theo. Glenwood," Horace G. S., C. Reynolds, George P., Addie and Minnie Goodnow, Frank Harris, Frank Fowler, W. H. W., Jessie I. Sturgis, Gordon C., Willie A. Kyh, G. M. Brockway, Arthur Mills, Katty Voorhees, Joseph A. U., May Harvey, C. E. C., Pierre F. C., Bertha Young, E. G. R., Nettie Carleton, Albert A. Bosworth, Mary S. Talbot, Samuel Maurer, Percy L., F. G., Diana S., Oswald, C. W. L., Mattie E. Wilson, F. R. Newton, May H.