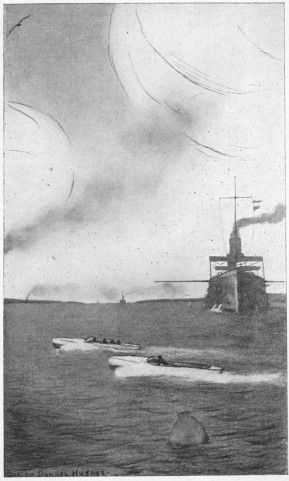

None Suspected the Meaning of What They Saw

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Launch Boys' Adventures in Northern Waters, by Edward S. Ellis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Launch Boys' Adventures in Northern Waters Author: Edward S. Ellis Illustrator: Burton Donnel Hughes Release Date: June 20, 2008 [EBook #25849] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LAUNCH BOYS' ADVENTURES *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE LAUNCH BOYS SERIES

THE LAUNCH BOYS ADVENTURES

IN NORTHERN WATERS

THE LAUNCH BOYS SERIES

Timely and fascinating stories of adventure on the water, accurate in detail and intensely interesting in narration.

—BY—

EDWARD S. ELLIS

First Volume

THE LAUNCH BOYS’ CRUISE IN THE

DEERFOOT

Second Volume

THE LAUNCH BOYS’ ADVENTURES IN

NORTHERN WATERS

The Launch Boys Series is bound in uniform style of cloth with side and back stamped with new and appropriate design in colors. Illustrated by Burton Donnel Hughes.

| Price, single volume | $0.60 |

| Price, per set of two volumes, in attractive box | $1.20 |

THE LAUNCH BOYS SERIES

The

Launch Boys’ Adventures

In Northern Waters

BY

EDWARD S. ELLIS

Author of “The Flying Boys Series,”

“Deerfoot Series,” etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

BURTON DONNEL HUGHES

THE JOHN C. WINSTON COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright, 1912, by

The John C. Winston Company

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A Proposal and an Acceptance | 9 |

| II. | The Scout of the Kennebec | 19 |

| III. | At the Inlet | 29 |

| IV. | A STRANGE RACE | 40 |

| V. | The Loser of the Race | 51 |

| VI. | A Warm Reception | 62 |

| VII. | Science versus Strength | 72 |

| VIII. | The Lone Guest | 83 |

| IX. | A Break Down | 93 |

| X. | At Beartown | 104 |

| XI. | At the Post Office in Beartown | 115 |

| XII. | Hostesses and Guests | 126 |

| XIII. | An Incident on Shipboard | 137 |

| XIV. | “The Night Shall be Filled with Music” | 147 |

| XV. | A Knock at the Door | 155 |

| XVI. | Visitors of the Night | 166 |

| XVII. | “Tall Oaks from Little Acorns Grow” | 177 |

| XVIII. | A Clever Trick | 188 |

| XIX. | In the Nick of Time | 198 |

| XX. | “I Piped and Ye Danced” | 208 |

| XXI. | How It Was Done | 219 |

| XXII. | A Startling Discovery | 230 |

| XXIII. | Through the Fog | 242 |

| XXIV. | Bad for Mike Murphy | 252 |

| XXV. | What Saved Mike | 263 |

| XXVI. | The Good Samaritans | 273 |

| XXVII. | An Unwelcome Caller | 284 |

| XXVIII. | Plucking a Brand From the Burning | 296 |

| XXIX. | “The Beautiful Isle of Somewhere” | 307 |

| XXX. | A Through Ticket to Home | 318 |

| XXXI. | Gathering Up the Ravelled Threads | 329 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| None Suspected the Meaning of What They Saw | Frontispiece |

| Like a Swallow Skimming Close to the Surface. | 233 |

| “Give Me Your Hand on That.” | 292 |

The Launch Boys’ Adventures

in Northern Waters

Alvin Landon and Chester Haynes were having a merry time in the home of Mike Murphy, when a servant knocked and made known that a caller was awaiting Alvin in the handsome bungalow belonging to his father. I have told you how the boys hurried thither, wondering who he could be, and how they were astonished to find him the “man in gray,” who had become strangely mixed up in their affairs during the preceding few days.

But Alvin was a young gentleman, and 10 asked the stranger to resume his seat, as he and Chester set the example. They noticed that the visitor was without the handbag which had hitherto seemed a part of his personality. Self-possessed and vaguely smiling, he spoke in an easy, pleasant voice:

“Of course you are surprised to receive a call from me.” He addressed Alvin, who replied:

“I don’t deny it. Heretofore you have seemed more anxious to keep out of our way than to meet us.”

“I admit that it did have that look, but the cause exists no longer.”

This remark did not enlighten the youths. Chester for a time took no part in the conversation. He listened and studied the man while awaiting an explanation of what certainly had the appearance of a curious proceeding.

“I don’t understand what could have been the cause in the first place,” said Alvin, “nor why my friend and myself should have been of any interest at all to you.” 11

The other laughed lightly, as if the curt remark pleased him.

“I have no wish to play the mysterious; my name is Stockham Calvert.”

It was Alvin’s turn to smile, while Chester said meaningly:

“That tells us mighty little.”

“I am one of Pinkerton’s detectives.”

The listeners started. They had never dreamed of anything of this nature, and remained silent until he should say more.

“You are aware,” continued the mild spoken caller, “that there have been a number of post office robberies in the southern part of Maine during the last six months and even longer ago than that.”

The boys nodded.

“A professional detective doesn’t know his business when he proclaims his purpose to the world. He does so in the story books, but would be a fool to be so imprudent in actual life. Consequently you will think it strange for me to take you into my confidence.”

“I don’t doubt you have an explanation to give,” suggested Alvin. 12

“I have and it is this. Without any purpose or thought on your part you have become mixed up in the business. The other night you gave me great help, though the fact never entered your minds at the time. You located their boat in a small inlet at the southern extremity of Barter Island.”

At this point Chester Haynes asked his first question:

“How do you know we did?”

Mr. Stockham Calvert indulged in a low laugh.

“Surely I did not follow you thither without learning all you did. Your conversation on the steamer gave me the information I wished. I did not expect you to succeed as well as you did.”

“Why did you avoid us? Why didn’t you take us into your confidence from the first?” asked Chester.

“I had several reasons, but I see now it would have been as well had I done so. However, let that go. My errand here to-night is to ask you whether you will not assist me in running down these criminals.” 13

The abrupt proposition caused a start on the part of the youths, who looked wonderingly into each other’s face. It was Alvin who replied:

“Assist you! What help can we give?”

“You have the fleetest motor boat on the Maine coast. It must be capable of twenty miles an hour.”

“It is guaranteed to make twenty-four.”

“Better yet. These men have a boat which closely resembles yours.”

“And its name is the Water Witch,” said Chester. “I wish Captain Landon could run a race with it.”

“He can have the chance if he will agree.”

“I fail to see how. Those men after committing their crimes are not going to spend their time in running up and down the Sheepscot or Kennebec.”

“Not wholly, but I don’t see any particular risk they incur in doing so. If they are pressed hard they can put into some bay or branch or inlet and take to the woods.”

“Still I do not understand how we can help you, Mr. Calvert,” said Alvin. 14

“It is possible you cannot, but more probably you can. While cruising in these waters, we may catch sight of their boat, and you can see the advantage of being able to outspeed it. But do not think I am looking for a battle between you and me on the one hand, and the criminals on the other. I wish to employ the Deerfoot as a scout. I can’t express myself better than by that word.”

Whatever the right name of the caller might be, he was a good judge of human nature. He saw the sparkle in the eyes before him. While the lads would not have been averse to a scrimmage, neither dared incur such risk without the consent of his father, and you do not need to be told that such consent was out of the question.

“As I understand it, then, our boat promises to be useful to you solely on account of its speed?” said Alvin inquiringly asked the detective.

“Precisely. What is your answer?”

The young Captain looked at his second mate. 15

“How does it strike you, Chester?”

“I’m with you if you wish to make the experiment. If things don’t turn out as we wish we can withdraw at any time.”

“Of course I shall expect to pay you for your services——”

“Then you will be disappointed,” interrupted Alvin crisply. “The Deerfoot isn’t for hire, and if we go into this it will be for the fun we hope to get out of it.”

“I think I can guarantee you some entertainment. I presume you two will be the only ones on the boat beside myself.”

“You mustn’t overlook my first mate, Mike Murphy. It would break his heart if we should go on a cruise and leave him behind.”

“I am afraid he is too impetuous and too fond of a fight.”

“He may have a weakness in those directions, but his good nature, pluck and devotion to my friend and me more than make up.”

“It strikes me——”

“I can’t help how it strikes you,” broke in Alvin, who did not intend to accept any 16 commands at this stage of the game. “Mike goes with us wherever we go.”

“I feel the same way,” added Chester. “The Deerfoot can never brave the perils of the deep short-handed. The first mate is indispensable.”

“As you please then. When will you be ready to start?”

“When do you wish us to start?”

“Say to-morrow morning?”

“This is so sudden,” said Alvin, whose spirits rose at the prospect of the lively times ahead. “We ought to have a little while to think it over. However, if my second mate, who generally has views of his own, will agree, we’ll get under way to-morrow after breakfast.”

“I’m wid ye, as Mike would say.”

“Suppose, Mr. Calvert, we leave it this way: if we decide to go into this business, we’ll make the venture to-morrow morning.”

“I shall stay at the Squirrel Inn to-night and be on the wharf a little before nine, on the lookout for you. If you do not show up then or soon after I shall not expect you. Your boat will be in plain 17 view all the time, so I shall see you when you start.”

“Why not stay with us over night? We shall be glad to have you do so,” was the hospitable invitation of Alvin Landon.

“Thank you very much,” replied Stockham Calvert, rising to his feet; “but I came over in a rowboat which is waiting to take me back. I engaged my room at the inn this afternoon.”

He bade them good night and walked briskly down the slope. The boys stood in front of the bungalow until they heard the sound of the oars and saw the dim outlines of the boat and its occupants heading eastward toward the twinkling lights from the inn and cottages on Squirrel Island.

“What do you make of it all?” asked Alvin of his chum, when after some minutes they returned to the big sitting room.

“I don’t know how to answer you,” replied Chester. “It looks to me as if we are bound to have lively times before we get through with the business. But, Alvin, all the time that man was talking I 18 felt a curious distrust of him. He said he is a detective, but I’m not sure of it.”

“Suppose he belongs to the gang that is playing the mischief with Uncle Sam’s post offices in this part of the Union?”

“If that were so, what in the world can he want of you and your boat?”

“Because of its fleetness it may serve him when he needs it. However, I don’t see that any harm can come to it or to us. He can’t pick up the launch and run away with it and he would find it hard to do so with us.”

“Not forgetting Mike Murphy.”

“Then you accept his proposal?”

“Not I, but we together.”

“All right; it’s a go.”

AT nine o’clock on a bright sunshiny morning in August the usual group were gathered on the dock at Squirrel Island. Some were watching the arrival and departure of the different steamers, not forgetting the little Nellie G., plying between that summer resort and Boothbay Harbor, some three miles distant, with calls at other islands as the passengers wished. Sailboats were getting ready to take parties out, some to fish, while others sought only the pleasure of the cruise itself. Small launches came up to the low-lying float for men and women to get on board, while others were rowed out in small boats to the anchored craft.

By and by the attention of most of the spectators was fixed upon the beautiful Deerfoot, which, putting out from the lower end of Southport Island opposite, was heading toward Squirrel. The picture had become 20 familiar to all and they admired the grace and symmetry of the launch which had won the reputation of being the swiftest of its kind in those waters. It was known that she was owned by Alvin Landon, the son of a millionaire who had built a handsome bungalow on Southport, where he was expected to spend his vacation days, though, as we know, he passed precious few of them there. Alvin was holding the wheel of his boat, while directly behind him sat his chum, Chester Haynes, calmly watching their approach to the floating dock.

The third member of the crew was our old friend Mike Murphy, whose official rank was first mate. Instead of sitting among his companions, the Irish lad had gone to the stern, where he sat with his legs curled up under him tailor fashion. He could not get much farther in that direction without slipping overboard. The figure of Mike was so striking that he drew more attention than did his comrades or the boat itself. His yachting cap was cocked at a saucy angle, revealing his fiery red hair, while underneath it was his broad, 21 crimson face, sprinkled with freckles, and his vast grin revealed his big white teeth. It will be remembered that the remainder of his costume was his ordinary civilian attire, though Captain Alvin Landon had promised him a fine suit for the following season. The time was too short to secure one for the present occasion.

Mike’s good-natured grin awoke more than one responsive smile among the crowd on the dock. The universal opinion was that the youth from the Emerald Isle was so homely of countenance that he couldn’t be any homelier, but at the same time none could be more popular. He knew that the eyes of nearly every one were fixed upon him and he in turn scanned the different faces, all of which were strange to him.

Alvin Landon slowed down as he approached and guided his boat among the others with the skill of a professional chauffeur weaving in and out of a procession of carriages. He gave his whole attention to this task, Chester watching the performance with the admiration he had felt many times before. But it was the people who 22 interested Mike. Before the boat rounded to, Stockham Calvert, the detective, accompanied by Lawyer Westerfield, of New York, walked down the inclined steps to the float. Westerfield was a gentleman of culture, an authority on many questions and one of the greatest baseball fans in the country. Having secured a liberal money contribution from Calvert the night before at the Inn, he invited him to stay and witness the great struggle between the Boothbay nine and the Squirrel Islanders. Westerfield was to act as umpire, his impartiality and quickness of perception having won the confidence of all parties; but of course Calvert had to decline under the pressure of a previous engagement.

“It does a fellow good to look at that broth of a boy squatting on the stern,” remarked Westerfield, while the Deerfoot was still a short distance away.

“His name is Mike and he is a great favorite with every one. As yet I have not met him, but he has all the wit and humor of his people. Suppose you test him.” 23

Nothing loath, Westerfield, who was a bit of a wag himself, called so that all heard him:

“You don’t need to show a red signal light, my friend; you ought to wait until night.”

Cocking his head a little more to one side, and with a slight extent of increase in the width of his grin—admitting that to be possible—Mike called back:

“Thin why have ye the graan light standing there on the wharf?”

Westerfield joined in the general laugh, but came back:

“That face of yours will keep off all danger by daylight.”

“And it’s yer own phiz that will sarve the same purpose at night.”

The laughter was louder than ever, and the pleased Calvert said to the lawyer:

“Better let him alone; he will down you every time.”

But Westerfield could not refuse to make another venture. Stepping back as if in alarm from the launch, which was now within arm’s reach, he feigned to be scared. 24

“Please don’t bite me with those dreadful teeth.”

Mike, who was now close to the wharf, leaped lightly upon it.

“Have no fear; the sight of yersilf has made a Joo of me.”

Then as if afraid that the listeners would not catch the force of his words, he added:

“A Joo, as ye may know, doesn’t ate pork.”

Detective Calvert slapped the lawyer on the shoulder.

“Try him again.”

“No; I have had enough.” Then raising his hat and bowing in salutation, Westerfield offered his hand to the lad, who shook it warmly.

“You’re too much for me, Mike. I’m proud to take off my hat to you.”

“And it’s me dooty to be equally respictful, as me dad said whin the bull pitched him over the fence and stood scraping one hoof and bowing from t’other side.”

While still in the boat, Alvin and Chester had returned the salutation of Calvert. The Captain remained seated at the wheel, 25 but the second mate stepped out on the float and a general introduction followed. The detective and he went aboard and sat down on one of the seats. Mike kept them company, and throwing in the clutch, Alvin guided the launch into the spacious waters outside, all three waving a salute to Westerfield, who stood on the float and watched them for some minutes.

Detective Calvert had the good sense fully to admit Mike Murphy to his confidence, though he had hoped at first he would not be a member of the party. Alvin Landon gave the man to understand that he was not hiring out his boat, but was conferring a favor upon the officer, who had the choice of rejecting or accepting it on the terms offered. While Calvert could not doubt the loyalty of the young Hibernian, he distrusted his impulsiveness. But as I have said, having decided upon his line of conduct, he did not allow himself to show the slightest degree of distrust.

Mike on his part was tactful enough to act as listener while the man made clear his plans. He did not ask a question or 26 speak until addressed. The launch moved so quietly that Alvin, with his hands upon the wheel and scanning the water in front, heard all that was said by the others, and when he thought it fitting took part in the conversation.

Instead of returning to Southport, the Deerfoot circled Cape Newagen, which you know is the southern extremity of that island, and entering the broad bay, headed up the Sheepscot River, over the same course it had followed before.

“Mike was not with you,” said Detective Calvert, “when you traced the other launch into that little inlet at the lower end of Barter Island. That boat stayed there overnight and may still be there, but probably is not.”

“Suppose it isn’t there?” said Chester.

“We must find out where she is. That is the chief reason for my presuming upon the kindness of the Captain to lend me the help of his launch. In other words, it is my wish that the Deerfoot shall serve as the Scout of the Kennebec.”

“A romantic title,” remarked Alvin, over 27 his shoulder, “though we are not cruising on the Kennebec, but up the Sheepscot.”

“No doubt we shall have to visit the larger river. And then, you know,” added Calvert, with a smile, “the name I suggest sounds better than the other.”

The launch required no special attention just then, and, with one hand on the steering wheel, Captain Alvin looked around:

“Mike, what do you think of it?”

“Arrah, now, what’s the difference what ye call the boat? At home, I was sometimes referred to as the Queen of the May, and again as the big toad that St. Patrick forgot to drive out of Ireland, but all agraad that I was as swate under one title as the ither.”

“Suppose the Water Witch happens to be where Chester and I saw her at night?” asked Alvin of their director.

“We shall have to decide our course of action by what develops.”

Neither of the youths was fully satisfied with this reply. They could not believe that a professional detective would come this far upon so peculiar an enterprise 28 without having a pretty clear line laid out to follow. It may have been as he said, however, and he was not questioned further.

The day could not have been finer. The threatening skies of a short time before had cleared and the sun was not obscured by a single cloud. Though warm, the motion of the launch made the situation of all pleasant. Since there was no call for haste, Calvert suggested to the Captain that he should not strain the engine, and Alvin was quite willing to spare it. The time might soon come when it would be necessary to call upon the boat to do her best, and he meant she should be ready to respond.

Past the Cat Ledges, Jo and Cedarbrush Islands moved the Deerfoot like a swan skimming over the placid waters. Then came Hendrick Light, Dog Fish Head, Green Islands and Boston Island. Powderhorn was passed, and then they glided by Isle of Springs, which brought them in sight of Sawyer. A little beyond was the inlet where they had seen the Water Witch reposing in the darkness of night.

“SLOW down,” said Detective Calvert as the launch drew near the southern end of Barter Island. Captain Alvin did as requested and all eyes were fixed upon the inlet.

“If that boat should happen to come out while we are in sight,” added Calvert, “pass up the river, as if you had no interest in it.”

“But if it should happen to be there?” said Alvin, repeating the question he had asked before.

“We can’t know until we have turned in, and then it would not do to withdraw, for that would be the most suspicious course of all. You have as much right to go thither as anyone. Act as if you were merely looking in out of curiosity; make a circuit of the islet and then come back and go on up the Sheepscot toward Wiscasset.” 30

It was at this moment that Mike Murphy asked a question whose point the others were quick to perceive.

“If the spalpeens are there, will ye let ’em have a sight of yersilf?”

“No; I shall drop down and hide, for if they noted that you had me for a passenger they might smell a rat, but would think nothing of seeing you three, for they know you travel together.”

As the launch drew near the opening, Alvin slackened her speed still more until she was not going faster than five or six miles an hour. There was an abundance of sea room and he curved into the passage with his usual skill. The four peered intently forward and had to wait only a minute or two when the boat had progressed far enough to give them a full view of the crescent-like cove, which extended backward for several hundred yards and had an expansion of perhaps four hundred feet. In the very middle was the islet, in the form of an irregular oval, containing altogether barely an acre. As has been said, it was made up of clay and sand 31 with not a tree or shrub growing, and only a few scattered leaves of grass, but there was no sign of life on or about it.

Alvin sheered the boat close to the shore, and continued slowly moving. A glance downward into the crystal current showed that the depth was fully twenty feet, so that it was safe for the largest craft to moor against the bank.

“Here’s where the Water Witch lay,” said Alvin. “Do you wish to land, Mr. Calvert?”

He was standing up and scrutinizing the little plot as they glided along the shore, but discovered nothing of interest.

“No; there’s no call to stop; we may as well go back.”

“Do ye obsarve that six-masted schooner wid its nose poked under the bushes in the hope of escaping notice?”

As Mike Murphy asked the question he pointed to the southern shore of the inlet, where all saw the little rowboat in which Detective Calvert had visited the spot and which had been used later for a similar purpose by Alvin and Chester. It 32 was drawn up so far under the overhanging limbs that only the stern was in sight. It seemed to be exactly where it had been placed by the boys after they were through with it.

It was on the tip of Alvin’s tongue to refer to the incident and to ask something in the way of explanation from their companion. Instead of doing so, the latter surprised both by saying:

“That must belong to somebody who lives in the neighborhood.”

The remark sounded strange to our young friends and both remained silent waiting for him to say more, but he did not. He sat down again, facing the Sheepscot, and lighted one of his big black cigars. He crossed his legs like a man of leisure who was not concerned by what had occurred or was likely to occur.

The incident impressed Alvin and Chester unfavorably. Mike, not having been with them at the time, knew nothing of it. To each of the former youths came the disquieting questions:

“Does he believe we did not know him 33 that night? Does he think neither of us suspected what he did? Is he what he pretends to be?”

These queries opened a field of speculation that was endless, and the farther they plunged into it the more mystified they became. Alvin would never stoop to ask favors of this man. He was trying to aid him in carrying out a good purpose, and he must “be on the level,” or the Captain would have nothing to do with him or his plans.

“The first proof I get that he is playing double,” muttered Alvin, “I’ll order him off the boat and never let him set foot on it again, and, if he belongs to that gang of post office robbers, I’ll do everything I can to have him punished.”

One of the most discomforting frames of mind into which any person can fall is to see things which make him distrust the loyalty of one upon whom he has depended. It might be Alvin Landon was mistaken and Stockham Calvert was in reality a Pinkerton detective whose sole aim was to bring these criminals to justice; 34 but, as I have shown, the full truth was still to be learned.

And Chester Haynes’ feelings were the same as those of his chum. He glanced at the man who was puffing his perfecto, and wondered who he really was and what was to be the end of this curious adventure upon which he and Alvin had entered.

It was a brief run out to the Sheepscot, and the Deerfoot headed up the river again toward Wiscasset. A steam launch was seen off to the left and a catboat skimmed in the same direction with our friends. Both were well over toward Westport, the left-hand bank, and slight attention was given them.

The Deerfoot had not reached the upper end of Barter Island when Alvin from his place as steerer called out:

“That looks like the boat we are hunting for.”

Running closer in to the right shore than the Deerfoot, a second boat was visible whose similarity of appearance caused astonishment. The bows of the two being pointed toward each other, the view was 35 incomplete at first, but since the speed of each was all of ten miles an hour, they rapidly came opposite. Alvin sheered to the left, so as to make an interval of a hundred yards between them. Chester had caught up the binoculars and kept watch upon the launch, his companions doing what they could without the aid of any instrument.

“It’s the Water Witch!” said Chester excitedly.

A minute before he did so, Detective Calvert quietly slipped from his seat to the floor, removed his hat and cautiously peered over the taffrail. But he did not cease smoking his huge cigar, and it struck Alvin when he looked around that his head was high enough to be in plain sight of anyone watching from the other craft.

Mike Murphy caught the stir of the moment.

“How many passengers do ye obsarve on the same frigate? It seems to me there be only two.”

“That is all that are visible,” replied Chester, holding the glass still leveled. 36

“Thin they must be them two that we had the shindy wid the ither night!”

“Undoubtedly; in fact I recognize the one you pointed out at Boothbay.”

“And the ither must be the ither one.”

“There is every reason to believe so.”

“Thin——I say, Captain,” said the agitated Mike, turning to Alvin, “would ye be kind enough to run up alongside that ship?”

“Why do you wish me to do that?”

“I wish—that is—I wud like to shake hands wid that gintleman and ask him how his folks was whin he last heerd from them. Just a wee bit of friendly converse betwaan two gintlemen—that’s all. Come now, Cap, be obliging,” continued Mike, in a wheedling tone which did not deceive his superior officer.

“I faal a sort of liking for the young gintleman and should be much pleased if ye would give me a chance to have a few frindly words wid him—I say, Cap, ye’re losing vallyble time, fur we’re passing each ither fast.”

“No, Mike—not to-day; I have no objection 37 to your having a little ‘conversation’ with Mr. Noxon or his companion, but this isn’t the right way to go about it.”

“I hope ye didn’t suspict that I had any intintion of saying harsh wurruds to them, Cap!” protested the Irish youth, in grieved tones.

“Not words particularly, but there would be enough rough acts to make things lively. Chester, let me have the glasses, while you take the wheel for a few minutes.”

They hastily exchanged places, and steadying his position, Alvin pointed the instrument at the receding launch. Detective Calvert still knelt on the floor and peeped over the side of the boat. He did not ask for the binoculars nor did the owner offer them to him.

Suddenly Alvin slipped down beside his friend in front and passed him the instrument, as he resumed the wheel. While doing so, he whispered in a voice so low that no one else could hear what he said:

“Look just behind the fellow who is steering. He’s Noxon, I’m sure! Study 38 closely and let me know whether you see anything suspicious.”

Wondering to what he referred, Chester complied. While doing his best to learn what his friend meant the latter whispered again:

“If you see anything, be careful to let no one besides me know what it is.”

Chester nodded, with the glasses to his eyes. The opportunity for scrutiny was rapidly diminishing. Chester held the binoculars level but a minute when he lowered them again. The commonest courtesy compelled him to offer them to the detective.

“Maybe you can discover something,” remarked the youth as he passed them over. The posture of the man gave him the best chance he could ask, and he carefully studied the receding boat until it was so far off that it was useless to continue.

“Did you notice anything special?” asked Chester.

“I saw nothing but those two young men, with whom as I learn from the Captain he had an affray some nights ago.” 39

Chester leaned over and whispered to Alvin:

“I saw it plainly.”

“What?”

“A man crouching down among the seats as Calvert did and peering over like him.”

Suddenly the Water Witch’s whistle sent out a series of piping toots.

“What’s the meaning of that?” asked Chester of Detective Calvert, who had quietly resumed his seat in one of the wicker chairs in front of the youth.

“It’s a challenge to a race.”

“I accept it,” said Alvin, with a flash of his eyes. At the same moment he swung the wheel over and began circling out to the left, so as to turn in the shortest possible space. “If that boat can outrun me I want to know it.”

“Be keerful ye don’t run over him,” cautioned Mike, catching the excitement, “as Tam McMurray said whin he started to overtake a locomotive.”

Alvin quickly hit up the pace of the launch, which sped down the Sheepscot with so sudden a burst of speed that all felt the impulse. The sharp bow cut the 41 current like a knife, the water curving over in a beautiful arch on each side and foaming away from the churning screw. Even with the wind-shield they caught the impact of the breeze, caused by their swiftness, and each was thrilled by the battle for mastery.

“Are you doing your best?” asked Calvert, watching the actions of the youthful Captain.

“No; I am making about two-thirds of the other’s speed.”

“Then don’t do any better, is my advice,” said the detective.

Alvin glanced over his shoulder.

“Why not?”

“It may be wise at this stage of the game not to let them know that you can surpass them. Wait till the necessity arises.”

“I agree with Mr. Calvert,” added Chester, and the Captain was impressed by the logic of the counsel. He was on the point of increasing the pace, but refrained. In truth he was already wondering what they would do if they overtook 42 the other and what could be gained by passing the boat.

Again the whistle piped several times and it was evident that the fugitive, as it may be called, had “put on more steam.”

“Do you wish me to let her get away from us?” asked Alvin.

“Not for the present, but that may be the best course. Hold your own for awhile and then gradually fall back.”

When the race opened, less than an eighth of a mile separated the contestants. The abrupt burst lessened this slightly and then it appeared to be stationary as the two glided down the river.

Such were the relative positions when the Water Witch shot past Ram Island, holding the middle of the stream, and a few minutes later came abreast of Isle of Springs.

“Those two young fellows have a man with them,” remarked Calvert. “He tried to keep out of sight when we first met, but now he doesn’t seem to care. You can see him plainly without the help of the glasses.” 43

Such was the fact, and Chester said:

“They must know that we also have a friend with us.”

“I don’t see that it matters either way. I think you are gaining.”

“But not half fast enough,” added Mike, who was standing and impatient to beat their opponent. “We must come up wid the spalpeens before they git to Boothbay.”

“They are not heading for Boothbay,” observed Calvert, whose keen eyes had detected the change in the line of flight. His companions saw he was right. The front boat had made so abrupt a change of course that it was almost at right angles to that of the pursuer. The side of the launch was exposed, showing the two youths, one of whom held the wheel, while the man with a mustache sat directly beside the other. It might be said of the two craft and their crews that they were twins, so marked was their resemblance.

Naturally Alvin shifted his line of pursuit. You may recall that, opposite the Isle of Springs, Goose Rock Passage connects Sheepscot River with Knubble Bay, 44 which leads into Montsweag Bay, reaching northward on the western side of the long island of Westport. In their first trip northward our young friends had gone to the eastward of Westport, as they had been doing during this race. Montsweag Bay takes the name of Back River at the northern end of the island and that and the Sheepscot unite above before reaching Wiscasset.

The Water Witch dived into Goose Neck Passage past Newdick Point, where it turned northward into Knubble Bay. This is the path taken by the steamers from Bath and other places on the Kennebec when going to Boothbay Harbor, Squirrel Island and other points. To the westward of these bodies of water sweeps the noble Kennebec to the sea.

Just ahead was discerned a swiftly approaching mass of tumbling water, above which the deck, pilot house and puffing smokestack of a little steamer showed. This was the “pony of the Kennebec”—the Gardiner, plowing ahead in such desperate haste that one might well believe the 45 fate of a score of persons depended upon its not losing a half minute. Alvin took good care to give her plenty of room and saluted with several whistle toots. There was no reply. The captain merely glanced at the two craft and sped onward like an arrow from the bow of the hunter.

The Deerfoot rocked and plunged in the swell made by the steamer, which, spreading out like a fan from its bow, ran tumbling and foaming along the rocky shores, keeping pace with the headlong charge of the boat, and trying to engulf everything in its path. One small catboat that was tied to a rickety, home-made landing, after a couple of dives capsized, as if it were a giant flapjack under which a housewife had slid her turning iron.

“They’re gaining!” exclaimed Chester, who was closely watching the progress of the racers. “Do you mean to let them get away, Alvin?”

“Mr. Calvert will answer that question.”

“I do so by advising that you neither gain nor lose for the present.”

The Captain gave the launch a little 46 more power, and it became clear to all that the pursuer was picking up the ground, or rather water, that she had lost. Then for several minutes no difference in speed was perceptible. A space of a furlong separated the two when they shot past the point of land bearing the odd name of Thomas Great Toe, which is on the western side of the lower part of Westport, some two miles above Goose Neck Passage. Here the water is a mile in width, and is filled with islands of varying sizes, until the large bay to the northward is reached.

The Water Witch persisted in hugging the eastern shore, while her pursuer kept well out, as if to make sure of having plenty of room in which to pass her, when the chance came. But all the same the chance did not come. It was soon seen that the fugitive was drawing away from her pursuer. Mike Murphy fumed, but held his peace.

“It’s mesilf that hasn’t any inflooence here,” he reflected, “as I obsarved to mysilf whin dad and mither agreed that a thundering big licking was due me.” 47

“Can you overhaul her?” asked Detective Calvert.

“Easiest thing in the world; I can shoot past her as if she were lying still.”

“Well, don’t do it.”

Mike could remain silent no longer.

“That’s a dooce of a way to run a race! Whin ye find ye can bate the ither out of sight ye fall back and let her doot. That’s the style I used to run races wid the ither boys at school, but the raison was I couldn’t help it. If ye’ll allow me to utter a few words of wisdom I’ll do the same.”

Alvin nodded his head.

“It is that ye signal to that pirut ahead to wait and give us a tow, being that’s the only way we can howld our own wid ’em.”

Now while it was trying to Alvin and Chester to engage in a race of the nature described and voluntarily allow the contestant to beat them, when they knew they had the power of winning, yet they believed it was the true policy, since Detective Calvert had said so. They understood the disgust of Mike and could not forbear having a little fun at his expense. 48

“You see,” said Chester gravely, “those two young men who gave you and Alvin such a warm time the other night are on the other boat, and if we should come to close quarters with them they would be pretty sure to even up matters with you.”

Mike glared at the speaker, as if doubting the evidence of his ears.

“Phwat is that ye’re saying?” he demanded. “Isn’t that the dearest object of yer heart? I shall niver die contint till I squar’ matters wid ’em, and ye knows the same.”

“You forget,” added Calvert, with the same seriousness, “that they have a full-grown man to help them out.”

“And haven’t we a full-grown man wid us, as me dad said whin he inthrodooced me to his friends at Donnybrook, I being ’liven years old? Begorra, I’m thinking we haven’t any such person on boord.”

It was a pretty sharp retort, but the officer could not repress his amusement at the angry words. Alvin looked over his shoulder and winked at Calvert and Chester, making sure that Mike did not observe the 49 signal. In his impatience, he had turned his back upon them and was looking gloomily over the stern at the foaming wake.

“I wonder if there isn’t some tub along the shore that’ll put out and run us down. I hope, Captain, that whin we git back home ye’ll kaap this a secret from dad.”

“And why?”

“He’ll sure give me the greatest walloping of me life.”

“For what reason?”

“For consoorting wid a party that run away from the finest chance in the wurrld for a shindy. It’s a sin that can be wiped out in no ither way.”

“I’ll explain to him,” said Calvert, “that you couldn’t help yourself.”

“And it’s mighty little difference that will make, as Terry McCarthy said when he had the ch’ice of foighting two Tipperary byes or three Corkonians.”

“Wouldn’t your father prefer to have us bring you home safe and unhurt rather than to have your beauty battered out of you?” inquired the detective, with a solemn visage. 50

Mike, who had risen to his feet and was still staring over the stern, slowly turned and faced the questioner. Then, with an expression of contempt, he said:

“Ye haven’t the honor of an acquaintance wid me dad.”

A long, low bridge connects the western projection of Westport with Woolwich on the opposite bank, beyond which spreads Montsweag Bay, narrowing to Back River, which, as has been explained, joins the Sheepscot.

The draw had just been swung open when our friends came in sight of the bridge, and saw the Water Witch passing through. The bridge tender immediately began turning his lever with which he closed the draw. Alvin whistled to signify that he wished to follow the other, but seemingly the man did not hear him. His back steadily rose and fell, as he worked the handle of his contrivance, and the movable section of the structure slowly swung back in response.

“Isn’t that lucky now!” was the sarcastic exclamation of Mike.

“He wants to hilp ye fall back further behind the ither boat.”

“There may be something in that,” the Captain replied.

None the less, Alvin continued his tooting, without abating his speed. The tender, however, did not mean to tantalize them, and all quickly saw the cause of his action. A heavily loaded wagon had come upon the bridge from the Woolwich side, and waited while the draw was held open. The driver must have had a “pull” with the attendant, who immediately closed the draw so he could cross before the second boat passed through.

At this juncture fate showed how perverse she can be when in the mood. Directly over the draw, something connected with the wagon or the harness of the team got askew and the driver paused to set it right. Possibly it was pretence on his part, for many men will do such things, but, all the same, he took ten minutes before he climbed back on his seat and started his horses forward again. Alvin reversed the screw, so that the launch 53 became motionless when a few yards from the bridge.

I am afraid the driver purposely delayed the Deerfoot, for when Mike shouted an angry reproach, he looked around, put his thumb to his nose, twiddled his fingers, and then moved slowly over the rattling planks toward Westport.

“I suggist that ye turn about, Captain, and scoot for home,” was the ironical advice of the Irish youth.

“For what reason?”

“I’m afeard that man is real mad and he might take it into his head to git down off his wagon and saize aich of us by the nape of the neck as the boat goes through, and slam us down so hard he’d jar us.”

“Better wait, Captain, till he’s a little farther off,” advised Calvert; “there may be something in what Michael says.”

As for Mike, feeling he could not do justice to the subject, he held his peace for the moment.

Gliding through the draw and entering Montsweag Bay, the occupants of the Deerfoot were surprised to see nothing of 54 the other launch. She was as invisible as if she had been scuttled and sunk in fifty feet of water.

The right shore above the structure, belonging to Westport, slopes to the right, and something like a half mile above, this course is at right angles to the stream. It is really a peninsula, there being an inlet more than a mile long which divides it from the rest of Westport. This little bay is spanned by a bridge which forms a part of the highway that passes over the longer structure already referred to.

When Mike found the Water Witch had vanished, he pretended to be vastly relieved. He had dropped into his chair and now straightened up.

“But ain’t we lucky?”

“Why so?” asked Calvert.

“If we hadn’t been stopped at the bridge the ither boat might have broke down and we’d come up wid the same, and those chaps would have give us all a good spanking.”

“I am glad you are becoming so prudent,” said Calvert, with an approving nod. 55 “We must take Michael with us whenever we are likely to run into danger. Captain, if you don’t mind, you might tune up your boat a bit.”

“Better wait,” suggested Mike, “fur ye might gain on t’other one.”

Alvin now put on the highest speed of which the Deerfoot was capable. The bow rose, the stern settled down in the water, and the spray was flung high and splashed against the wind-shield. The exhaust deepened to a steady roar, and the broadening wake was churned into a mass of tumbling soapy foam. The whole boat shivered with the vibration of the powerful engine. She was going more than twenty miles an hour—in fact, must have approached her limit, which was four miles faster. Alvin had attained such a tremendous pace only a few times in his practice and did not like it. Though his instructor had assured him that the launch was capable of holding it indefinitely without injury, he feared a breakdown or the unnecessary wear upon many parts of the engine.

He kept up the furious speed until they 56 curved around the upper part of the peninsula and saw the expansion above, all the way to Long Ledge, where Back River begins. He had been confident of catching sight of the Water Witch, but she was nowhere in sight.

The natural conclusion was that the launch had taken on a higher burst of speed—probably the limit—and gone so far that by still keeping near the shore she had placed several miles behind her—enough to carry her out of the field of vision.

“Keep it up till we catch sight of her again,” suggested Calvert. “I believe there are no more bridges between us and Wiscasset.”

Some three or four miles were passed at high speed, when they reached a portion of the river which opened a view of still greater extent. They saw two small sailboats at a distance, and a little steamer puffing northward, but nothing of the Water Witch.

“You may as well slow down,” remarked the detective, who, guarding a match with 57 his hands behind the wind-shield, proceeded to light another cigar.

“What do you make of it?” asked Alvin, turning his head, as the pace became slower than before.

“We have passed the other boat; she is behind us instead of in front.”

“What shall we do?”

“For hiven’s sake don’t go back,” protested Mike. “Ye might find her—and then what would become of ye?”

The detective now gave his view of the situation.

“If we should turn round and find that boat, those on board would know we were looking for them. We don’t wish to give that impression, at least for some time to come. While we were going in one direction and they in another, they challenged us to a race. Any two boats might have done the same in the circumstances. We have to accept defeat and that’s all there is to it.”

Calvert looked at his watch.

“It is near noon; if you all feel as I do you would welcome a good dinner.” 58

“That’s the most sensible sense that I’ve heerd since we started,” remarked Mike, who was as hungry as his companions.

“It is not a long run to Wiscasset,” said Alvin; “and there’s more than one good hotel there.”

“I’m thinking that at the speed ye’re going, we’ll hardly arrive in time for supper. There must be some place betwixt here and the town where we can git enough to stay the pangs of starvation till we raich Wiscasset.”

“We shall pass several landings, and there are farmhouses along shore where I’m sure the folks will be glad to accommodate us.”

The others were not much impressed with Mike’s plan, but since there was plenty of time at their command, they fell in with it. Alvin suggested that all should keep a lookout for an inviting dwelling, when, if a good landing could be made, they would stop and investigate.

Chester offered to relieve his chum at the wheel, and Alvin was quite willing to exchange places with him. The occurrences 59 of the last hour or more, together with what was said by Detective Calvert, had increased the confidence of the youths in him. True, they could not understand the full object of this cruise up the river, after gaining sight of the launch and the occupants for whom he had been searching. They were content to await explanation on that point, but Alvin determined that one or two things which puzzled him and Chester should be cleared up.

“Accepting what you said last night at my home, Mr. Calvert, I must say for myself and friend that we do not understand some of your actions. Perhaps you won’t mind explaining them.”

“I shall be glad to do so, if it is prudent at this time.”

“You will pardon me for saying that in our opinion you acted foolishly when you followed us off the steamer the other day at Sawyer Island, pretended you had made a mistake in landing there, and then dogged us to that little inlet. We saw you several times, but you either wished or pretended you wished to keep out of our sight, as, for 60 instance, after crossing that long bridge from Hodgdon to Barter Island. You followed us, but when we stopped at the side of the road to wait for you, you slipped among the trees and made a circuit round the spot. Why did you do that?”

The detective smiled, and smoked a minute or two before replying.

“Perhaps it was undignified, though a man in my profession has to do a good many things in which he casts dignity to the winds. The truth is, I formed the intention of getting off at Sawyer as soon as I heard your friend Mr. Richards say he thought he had caught sight of your launch in that cove. I was trying to get track of the same parties, but prudence whispered to me that the time had not yet come in which you and I should hitch up together. I suspected it might soon be advisable, but not just then. My pretence of having left at the wrong landing was a piece of foolishness meant only to afford you and the agent a little amusement, but I feared you would run into trouble with those criminals and I decided to keep you under my eye. 61 Until I concluded to trust you, it was just as well that you should distrust me. For several reasons, which I won’t explain at this point, I came to the belief last night that it was time we made common cause.”

“I have me eye on the right place, as Father Mickle said whin he wint into the saloon to pull out Jim Gerrigan by the nape of his neck.”

Mike Murphy pointed to a small, faded yellow house which stood at the top of a gentle slope on their right. It was a hundred yards from the river and a faintly marked, winding path led from it down to the bank. The surrounding land showed meagre cultivation, and the looks were anything but inviting.

On the little porch sat a big man with grizzled whiskers, smoking a brier-wood pipe, his beamlike legs crossed and his arms folded as he moodily watched the launch.

“It strikes me as a poor promise,” remarked Alvin, who, nevertheless, asked Chester to steer to the shore to see whether a landing could be readily made. The prospect was good, as a shaky framework 63 had evidently been placed there for use, though no small boat was near.

Chester brought the Deerfoot alongside with the skill that the owner of the launch would have shown. Alvin sprang lightly upon the structure, which sagged under his weight, caught the rope tossed to him by Chester, and fastened it around one of the rickety supports. The boat was made fast.

“I’ll walk up to the house and have a talk with the gintleman,” said Mike, stepping carefully out upon the boards. “Do I look hungry?” he asked of Alvin, who replied:

“You always have that expression.”

“I’m glad to hear it, fur I wish to impriss the gintleman that that’s my condition. I’ll assoom a weak, hisitating walk. Do ye abide here aginst me return and repoort.”

Detective Calvert retained his seat and lighted another cigar. Chester sat with his hand idly resting on the wheel. Alvin kept his place on the tiny dock, and all three watched Mike Murphy. They smiled, for the stooping shoulders of the Irish youth 64 and his feeble gait were those of a man of four-score. The huge stranger sat like a statue, slowly puffing his pipe, his glowering eyes fixed on the approaching lad.

With each advancing step, Mike’s doubts increased. The nearer he came to the stranger, the more forbidding he appeared. Had the lad followed his inclination he would have turned back, but he knew his friends were watching him. Besides which, he was really hungry.

He had passed half the distance between the boat and the house, scrutinizing the scowling fellow all the time, when the latter made his first movement. He uncrossed his huge legs, took the pipe from between his lips and emitted a low whistle.

“He must be so cheered at sight of me that he is obleeged to give exprission to his feelings—Begorra!”

Around the end of the house dashed a mongrel dog, and halting abruptly with pricked ears, glanced at his master to hear his command. The canine was of moderate size, black and white in color, one eye wrapped about by an inky splash of hair 65 that made him look as if the organ was in mourning.

Holding the pipe away from his lips, the man pointed the stem toward Mike, who had paused, and said to his dog:

“Sick him, Nick! Sick him!”

And the dog proceeded to “go for” the caller. Had the latter run away, the brute would have been at his heels, nipping and biting at each step. But Mike had no thought of retreating. He was filled with anger at his inhospitable reception and gave his whole attention to the animal, which with a muttered growl charged full speed at him.

Mike noticed that a collar with projecting spikes encircled the stumpy neck, and never was one of his breed more eager to bury his teeth in a victim’s anatomy.

“This is going to be a shindy sure, as Micky Rooney said when he tackled five p’licemen—and I haven’t even a shillaleh in hand.”

Mike coolly braced himself for the shock, not yielding an inch nor turning his gaze from his foe. It was no longer a doddering 66 old man who faced the stranger, but a sturdy youth, muscular, brave and always eager for the fray.

Nothing could surpass the skill with which the first assault was repelled. At the exact moment Mike launched his shoe, the toe of which caught Nick under the jaw and caused him to turn a backward somersault. He uttered several yelps, but the blow added if possible to his rage.

The dog was so bewildered for the moment that he lost his sense of direction, and made a dash toward the porch where his master was watching proceedings.

“Sick him, Nick! Sick him!” he called, pointing his finger at the lad.

Nick impetuously obeyed orders, and at the critical moment Mike launched a second kick, which, however, was not delivered with the mathematical exactness of the first. It landed in the canine’s neck and drove him back several paces, but he kept his balance, and came on again with the same headlong fierceness as before.

It was at this juncture that Stockham Calvert flung away his cigar, sprang from 67 his chair and with one bound landed beside Alvin Landon.

“I don’t intend that Mike shall get into trouble.”

As he spoke, he laid his hand on his hip pocket where reposed his revolver.

“It looks as if it’s the dog that is in trouble,” replied Alvin, his cheek tingling with pride at sight of the bravery of his comrade.

“If he had to fight only one brute I shouldn’t fear, but there are two against him. When Mike is through with the dog he will have to face his master. I shall be ready to give him help.”

“You don’t mean to shoot the fellow?” said the alarmed Captain.

“It won’t be necessary,” was the quiet response.

The next exploit of Mike was brilliant. He did not kick at the dog, for that only deferred the decisive assault, but as the mongrel rose in air, he side-stepped with admirable quickness, gripped him by the baggy skin at the back of his neck, and, slipping his hand under the spiky collar, 68 held him fast. The brute snarled, writhed, snapped his jaws and strove desperately to insert his teeth into some part of his captor, who held him off so firmly that he could do no harm.

Mike now turned and began walking hurriedly toward the launch, with the squirming captive still in his iron grip.

The infuriated owner sprang from his seat and leaped down the steps.

“Drop that dog!” he shouted, striding after Mike, who called back:

“I’ll drop him as soon as I raich the river.”

Afraid of being checked, the youth broke into a trot, and an instant later was at the landing, the yelping mongrel still firmly gripped. Back and forth Mike swung him as if he were the huge bob of a pendulum, and then let go. He curved over the launch, like an elongated doughnut, and dropped into the current with a splash. But all quadrupeds swim the first time they enter the water. In an instant, the brute came to the surface, and working all his legs vigorously, came smoothly around the stern 69 of the launch, and headed for Mike with the purpose of renewing the attack.

The man, who had dropped his pipe and strode down the walk, was over six feet in height, of large frame, and manifestly the possessor of great muscular strength. Although he knew his dog had suffered no harm and was safe, he was enraged over his maltreatment and resolute to wreak vengeance upon the author of the insult.

Mike read his purpose, poised himself and put up his fists.

“Now for the next dog and it’s mesilf that is ready fur him.”

It would give me pleasure to tell how Mike Murphy vanquished the giant who attacked him, but such a statement would be as untrue as absurd. You have read of the dude who daintily slipped off his kid gloves, adjusted his eyeglasses, and proceeded to chastise an obstreperous cowboy; but take it from me that no such thing ever occurred, except in stories. Nature governs through rigid laws, and two and two will always make four. It might have been creditable to the courage of the Irish 70 youth thus to engage in a bout with a man who would have quickly beaten him to the earth, but it would have shown very poor judgment. Had they clashed there could have been only one end to the encounter.

But they did not clash. Several paces separated the two, when Stockham Calvert, his thin gray coat buttoned around his trim form, stepped quickly between them, and, looking sharply into the face of the savage stranger, said in a voice that showed not the least agitation:

“Stop! he’s my friend!”

He raised one hand, palm outward by way of emphasis of his warning words.

“Who are you?” demanded the other, stopping short, his eyes flaming above his shaggy beard and under his straw hat, like an animal glaring through a thicket.

“Come on and you’ll learn!” was the reply in the same even tones, as Calvert assumed the posture of a trained pugilist.

Now it is proper to say of this man that he had been the champion boxer in college, and in his New York club he was easily the master of every one with whom he had 71 donned the gloves. Though of only average size and stature and inclined to thinness, his muscles were of steel, he had the quickness of a cat, and had been told more than once, that if he would enter the “magic circle” he would hold his own with the best in the profession. But, like all gentlemen who are masters of the manly art, he disliked personal encounters, and many a time had submitted to insulting words and even the accusation of timidity, rather than to call his iron fists and superb skill into play. You might have been in his company for months without suspecting his attainments in that respect. His business required that he should always carry a revolver, and when he placed his hand on his hip at sight of Mike Murphy’s personal danger, the action was instinctive, but he instantly gave up all thought of using so deadly a weapon. He was certain there was no necessity for it; he had no more doubt of his mastery of the bulky brute, who was equally confident, than he had of his ability to handle any one of the three lads who were his companions.

Had the large man undergone the scientific training of the smaller one, he might have overcome him, for, as has been said, he was immensely powerful and must have been a third heavier than Stockham Calvert. But he was out of condition, and, worse than all for him, had not the slightest knowledge of the “manly art.” When he doubled his huge hairy fists, he charged upon the detective like a roaring bull, expecting to beat down his smaller antagonist as if he were pulp.

The pose of the defendant was perfect. Resting easily on his right foot, the left advanced and gently touching the ground, he could leap forward, backward or to one side with the agility of a panther. The left fist was held something more than a foot beyond the chest, the elbow slightly crooked, while the right forearm crossed 73 the breast diagonally at a distance of a few inches. This is the true position, and the combatant who knows his business always looks straight into the eyes of his opponent. The arms and body are thus in his field of vision, whereas if he once glances elsewhere he lays himself open to a sudden blow.

With that alertness which becomes second nature to a pugilist, Calvert saw before the first demonstration that his foe had no knowledge whatever of defending himself. He allowed him to make a single rush, his big fists and arms sawing space like a windmill. He struck twice, swishing the air in front of Calvert’s face, and gathered himself to strike again, when——

Not one of the three spectators could ever describe how it was done, for the action was too quick for the eye to follow. But, all the same, that metal-like left fist shot forward with the speed of lightning, and landing on the point of the chin, the recipient went down like an ox stricken by the axe of a butcher. Rather curiously, he did not fall backward, but lurched forward 74 and lay senseless, knocked out in the first round.

“You have killed him!” whispered the scared Captain.

“Not a bit of it, but he will be dead to the world for ten or fifteen minutes. We may as well let him rest in peace. What’s become of that dog?” asked the officer, glancing inquiringly around.

Chester pointed toward the house. The brute, with his two inches of tail aimed skyward, was scooting around the corner of the building as fast as his bowed legs could carry him. He would not have done so had he been of true bulldog breed, but being a mongrel, there was a big streak of yellow in his make-up.

“He’s come to the belief that it’s a good time to adjourn, as me cousin said whin someone blowed up the stump on which he was risting his weary body.”

“I think we have had enough foraging along the river,” remarked Captain Alvin, who re-entered the boat and resumed his place at the wheel. “We dine at Wiscasset.” 75

“I’m not partic’lar as to the place,” said Mike, “if only we dine.”

Chester flung the loop of rope off the support, and he and the others stepped aboard the launch, which moved up the river. Standing in front of the detective, Mike, with his genial grin, offered his hand:

“I asks the privilege of a shake of yours. I apologize for thinking ye didn’t like a shindy as well as the rest of us. I’m sorry for me mistake, as me uncle said, whin he inthroodoced dad to a party of leddies as a gintleman. I couldn’t have done better mesilf.”

The smiling officer cordially accepted the proffer.

“No one can doubt your pluck, Mike, but, to quote your favorite method of expressing yourself, you showed mighty poor judgment, as the owner of the bull said when the animal tried to butt a locomotive off the track. That man would have eaten you up.”

“P-raps, but he would have found me hard to digist. Do ye obsarve?”

He pointed to the little landing which 76 they were leaving behind them. All looked and saw the burly brute of a man slowly rise to a sitting posture, with his hat off and his frowsy hair in his eyes, as he stared confusedly after the launch speeding up the river.

“He is recovering quicker than I expected,” was the only remark Calvert made, as he turned his back upon the fellow and gave his attention to lighting another cigar.

“He has the look of a fellow mixed and confused like, similar to Pat McGuigan, whin he dived off the dock and his head and shoulders wint through a lobster pot that he didn’t obsarve in time to avoid the same.”

“He’s coming round all right,” said Calvert, referring to the man they had left behind, though he did not glance at him. “He may not be very pretty, but he knows more than he did a little while ago. Which reminds me to say something that ought to have been said at our first interview.”

The three listened to the words of Calvert, who clearly was in earnest. 77

“Each of you knows that I am a professional detective who has been sent into Maine to do all I can to capture the gang that is robbing the post offices in this section. I told you that much, but I wish to ask you to be very, very careful not to say this to any person whom you may meet, until you have my permission to do so. Some would insist that it was unprofessional on my part to say what I did, but I had good reason for it, as will appear before I am through with the business.”

“It was not necessary to tell Chester and me that, but I suppose you wish to run no risk that can be avoided.”

“That’s it; I did not doubt your loyalty, but you know we can’t be too careful.”

Mike was leaning back in his chair deeply thinking.

“There’s one waak p’int in the plan suggisted.”

Inasmuch as no one had submitted a plan the three wondered.

“Me friend doesn’t wish us to tell anyone that he’s the best detictive and scrapper outside of our family in Ireland, but when 78 folks priss their questions, some answer must be given or ’spicions will be stirred.”

“The point is well taken. I don’t wish you to tell an untruth——”

“I’m sure the task is not difficult fur the Captain and second mate,” interrupted Mike, “though it’s beyond me.”

“But you can evade a direct reply.”

“May I vinture upon another suggistion?” asked Mike.

“We shall all be glad to hear it, I’m sure.”

“Without waiting for questions to be asked, I’ll step up to ivery one that I obsarve casting an inquiring eye over ye and say ye’re my older brither, that took a hand in the Phoenix Park murders, but broke out of Dublin jail and thus escaped hanging, and yer kaaping dark in Ameriky till the little matter blows over.”

“A brilliant idea!” laughed the officer. “All I ask is that you give no truthful information about me.”

“Ye doesn’t objict to my telling folks how ye laid out that Goliah a bit ago?”

“I prefer you should not mention it.” 79

Mike sighed.

“Ah, have ye no pride of family, as Tam O’Toole used to say whin mintioning the fact that all his five brithers were in jail, where Tarn himsilf ought to have been?”

“I may add,” continued the man, “that it is quite likely we shall soon part company.”

Mike affected to be surprised.

“Doesn’t the Captain pay ye ’nough wages?”

“I have no fault to find on that score.”

“I’m glad to larn that. If he requires ye to do too much dooty, I’ll hilp ye out, the bist I can.”

“I promise to call upon you if necessary, Mike, but I hope I shall not be obliged to do so.”

“I have been wondering since we started,” said Alvin over his shoulder, “whether by any possibility the Water Witch kept on up the river ahead of us instead of running into some bay or inlet to the south.”

“It is possible, but not probable. You know we had an extended view of this stream, or rather of Montsweag Bay, and 80 she could not have gone far enough in the short time to pass out of sight.”

“Ye forgits how anxious the Captain was not to overtake her,” reminded Mike. “I once read of a farmer who chased a big black bear that had been staaling his sheep fur two days and nights and then quit. Can ye guess why?”

“I should say that after so long a chase he would have given up disgusted,” replied the detective.

“It was not that; it was ’cause he found the tracks were becooming too fresh.”

“I don’t think, Mike, that you are in danger of being accused of that,” ventured Chester, “because you are always fresh—you are never becoming so.”

“But the same is becooming to me, as Jim Flannery said whin he walked into church wid two black eyes and his head bent out of shape from the shindy he had with his twin brither over the quistion of aiting maat on Friday.”

“You seem quite sure that these three whom we saw in the launch are mixed up in these post office robberies?” asked Alvin. 81

“It has that look. No matter how certain I may feel, nothing can be accomplished until legal proof is obtained. You know the rule that every man must be presumed to be innocent until proved guilty.”

“It shtrikes me that the most important quistion of all has been sittled.”

“What’s that?”

“These two young gintlemen are the spalpeens that tried to hold ye up, Captain, the ither night on yer way home. That fur outweighs the taking of a few postage stamps from some country offices.”

“The puzzling feature of that business,” said Alvin, “is that when you meet those two fellows again, you will not have Mr. Calvert along to protect you.”

Mike stared as if he failed to catch the meaning of this astounding remark.

“Plaise say that agin, Captain, and say it slow like.”

Alvin’s face being turned away, he was not forced to maintain his gravity while he repeated in his most serious tones the remark quoted. 82

“All I have to say to that is not to say anything, as Teddy Geoghan observed whin they found a stolen pig in the bag he was carrying over his shoulder which the same he insisted was filled with clothes for Widow Mulligan.”

The Deerfoot glided through the smooth waters, and while the afternoon was still young rounded to at the wharf, below the long wooden bridge which spans the stream at Wiscasset, and made fast where a score of other boats of all sizes and models were moored. Several large vessels were anchored farther out and Captain Alvin Landon had to slow down to thread his way among them. There was plenty of room, and the launch was tied up opposite a small excursion steamer which was to start southward an hour later. A tip to the old man who was looking after a number of yachts assured the safety of the last arrival from molestation.

The possibility that the Water Witch had preceded them to Wiscasset caused a scrutiny of the various craft in sight by the Captain and his crew, including Detective 84 Calvert, but nothing was seen of the boat.

“She is miles off down stream,” was the remark of the officer, “and for the present is out of the running.”

The four walked up the easy slope to the main street, along which they passed to the leading hotel for dinner. They were a little late and when they went into the spacious dining room found a table by themselves. The only other occupant was a tall, angular man of about the same age as Calvert, similarly attired and apparently giving his sole attention to the meal before him. He nodded to the group in a neighborly way, but did not speak.

When the four took their places at the small table, Calvert faced this person a short distance away; Chester Haynes sat with his back to him, thus confronting the detective, while Mike and Alvin occupied the respective ends of the board. These details sound trifling, but they had a meaning. Calvert thus distributed his companions apparently off-hand, but the seating of himself as mentioned was done with a 85 purpose. Chester then, from the position he occupied, was the only one of the other three who observed anything significant in that action and in what followed.

In the first place, the officer raised his glass of water, and while slowly drinking looked over the top at the lone guest. Chester noticed that he sipped the fluid longer than common, gazed at the stranger and deliberately winked one eye. What response the other made of course could not be seen by Chester.

“The two are acquaintances,” was the conclusion of the lad, “and they don’t wish anyone else to know it.”

He was curious to know whether Alvin and Mike had noticed anything of the by-play. The Irish lad for the time devoted himself to satisfying his vigorous hunger and cared for naught else. The same was to be said of the Captain. Chester remained on the alert.

Several trifling incidents that occurred during the meal, which was enlivened by the wit of the Irish lad, confirmed Chester in his first suspicion. Calvert tried to 86 divert possible suspicion by cheery remarks and pleasant conversation as the meal proceeded.

“I am sure, Mike, you never had any such feasts in the old country.”

Having said this, the detective coughed several times and held his napkin to his mouth, but Chester knew the outburst was forced, and was meant to carry to the other man, who rather curiously coughed the same number of times immediately afterward.

“A message and its reply,” was the thought of Chester, “but I have no idea of what they mean. Mr. Calvert doesn’t wish me to see anything and I won’t let him know I do.”

Meanwhile, Mike made his response to the inquiring remark of Calvert:

“Ye’re right, me frind, as Hank McCarthy said whin dining on one pratie and a bit of black bread, calling to mind his former feasting in his own home. Which reminds me, Mr. Calvert, to ask, did ye iver see the heart of an Irishman?”

“I’m not quite sure I grasp your meaning, 87 Mike,” was the reply, while Alvin and Chester looked up.

“I can bist explain by a dimonstration, as the tacher said whin I asked him what was meant by the chastisement of a school lad. Now, give heed, all of ye, and I’ll show ye what I meant by the sinsible inquiry.”

Among the different articles of food on the table was a dish of “murphy” potatoes with their “jackets” on. That is, they had not been mashed or peeled, though a strip was shaved off of each end. They were mealy and white, and Mike had already placed several where they were sure to do the most good. The tubers in boiling had swollen so much that most of the skins had popped open in spots from the richness within.

Mike reached over and carefully selected a big murphy, which he held with the thumb of his left hand and fingers circling about it. The upper end projected slightly above the thumb and forefinger, as if peeping out to watch proceedings. The three stopped eating for the moment and watched 88 the youth. While doing this, Chester glanced for an instant at the face of the officer, and saw him look quickly across the room and telegraph another wink.

Like a professional magician, Mike was very deliberate in order to be more impressive. The true artist does not overlook the minutest point, and he daintily adjusted the potato, shifting it about until it was poised exactly right. Then he slowly raised his open right hand, with the palm downward, until it was above his head. Like a flash he brought it down upon the upper end of the tuber, which shot through the loose encircling grasp as if fired from an air gun. The skin remained, but the potato itself whisked down upon the table with such force that it popped open, and lo!

“There’s the heart of an Irishman—Begoora! but I’m mistook!” exclaimed Mike in dismay, for when the tuber burst open the interior was black with decay!

Calvert threw back his head and roared, and Alvin and Chester came near falling from their chairs. Even the man at the other table joined in the boisterous merriment, 89 which was increased by the comical expression of Mike. With open mouth and staring eyes he sat dumfounded. For once in his life he was caught so fairly that he was speechless.

The deft little trick he had performed many times, but never before had he been victimized by what seemed to be a rich, mealy potato. He couldn’t understand it.

Oddly enough the stranger was the first to recover his speech. He must have had little liking for Hibernians, since he called:

“You’re right, young man! You showed us the heart of a real Irishman!”

With lower jaw still drooping, Mike turned his head and stared at the speaker. He yearned to crush him with a suitable reply, but all his wit had been knocked out of him by the cruel blow of fate. However, it could not long remain so. He picked up the fragments of the potato, fumbled them reprovingly and gravely laid them on the tablecloth beside his plate. Then the old grin bisected his homely face, and addressing the three, he said:

“I made a slight mistake, as Jerry Sullivan 90 said whin he stepped out of the third story windy thinking it was the top of the stairs. If it’s all the same to yees, we’ll now give our attintion to disposing of the remaining stuff on the boord.”

Out of curiosity, the four cut in two each of the potatoes left in the dish. Every one was as sound as a dollar, whereat all laughed again, Mike as heartily as any.

“It’ll be a sorry day whin I can’t take a joke, as Jim Doolin said smiling whin his frinds pushed his cabin over on top of him as he lay sleeping behind it, but I was niver sarved such a trick before.”

Chester thought the unanimous merriment caused by Mike’s mishap would open an acquaintance between the lone guest and the others, but nothing more was said by the respective parties, nor did the watchfulness of the youth detect any further signals while at the table. Evidently an understanding had been brought about, and nothing else was required.